“Putting Down and Letting Go”: An Exploration of a Community-Based Trauma-Oriented Retreat Program for Military Personnel, Veterans, and RCMP

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants, Recruitment, and Informed Consent

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

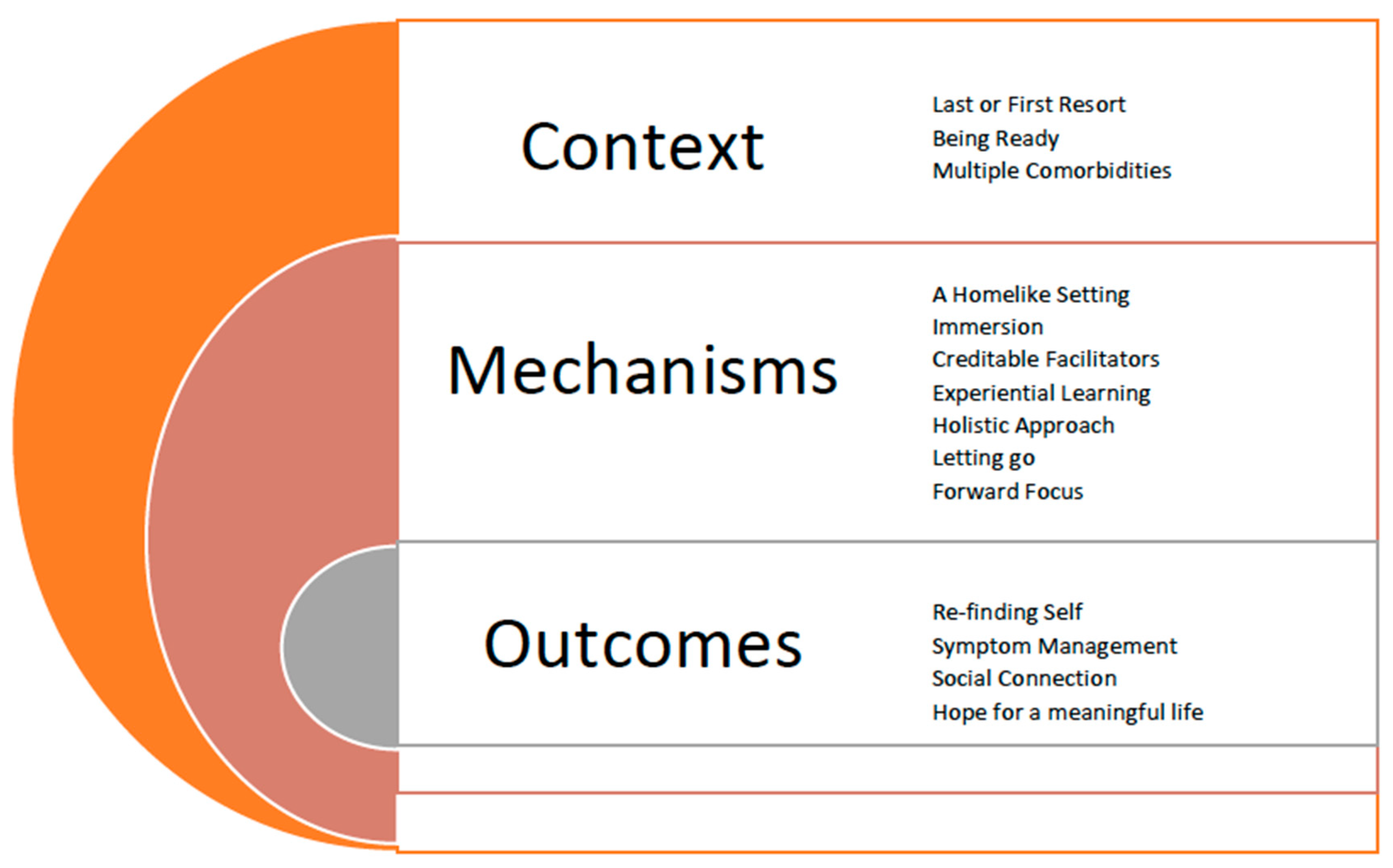

3. Results

3.1. Context

3.1.1. Last or First Resort

16-24 “I saw it as sorta my last chance because I just retired about a month-and-a-half ago so I saw that as my last chance at a kick at the can so to speak.”

30-25 “Everyone sees the bullet wound, and no one sees the mental wound and for me at work, I didn’t tell anyone.”

3.1.2. Being Ready

62-30 “I think when you go to this program you really have to be in a place where you want and need help and you have to be willing to participate and put the work in. So if you are just going there and kind of I don’t wanna say fake it and come out the same kind of person you were. So you have to really put in the work and bear your soul basically. You get out of it what you put into it and I think the guys in that cohort put everything into it and so I think they are all in a really good place.”

155-45 “I felt very raw going there... And what I felt at this point before I went I was like you know what, clearly what I am doing is not fixing the problem or my daily life was being consumed for the most part so clearly I needed to try something out of my comfort zone and be open-minded and try something different.”

3.1.3. Multiple Comorbidities

10-23 “I had not had the confidence or the strength because I’ve been and continually have chronic pain, so it was a challenge to do anything before… so I had really stopped doing anything... and going to [the program] put me back on track to kind of challenge myself a little bit more physically.”

147-46 “I was using a lot of drugs and drinking as well, so just yeah... so it’s hard because you know on the one hand [PLACE] and that treatment gave me what I needed at the time, but on the other, there was this big part of like connection and understanding and like compassion that I didn’t quite receive when I was seeking treatment for concurrent trauma and addiction.”

3.2. Mechanisms

3.2.1. A Home-like Setting

20-24 “So going there, the only thing that I had in my mind was if they open the door in a lab coat and a wheelchair and all that kind of stuff I am not going in. That’s bugged me since I was a kid, just being committed and that terrifies me because I can’t be trusted or my brain can’t be trusted, at least that’s how I take it. So right from the get-go, the location is great, it’s a beautiful piece of property and the bit of nature that we get to experience there is good. It’s nice that it’s not totally secluded.”

81-33 “I always felt comfortable in that situation because of the whole comfortable atmosphere of the place, everyone is loving, the mentors are understanding, they’ve all been through it before so the whole immersive experience I think makes it successful.”

3.2.2. Immersion—Being in the Grinder

105-39 “The immersion is critical because it just slowly wears you down, you are just in the grinder right and you can’t get out. And it breaks down your defences, and then you let go. It’s just freaking brilliant.”

103-38 “It’s quite different. You are doing 15 hour days, you are there for 6 days and every moment is filled with something. To get to that in an hour a week is almost impossible to get to that level of insight with yourself or what is going on, and even we were interacting with the group, it’s not really downtime you are still learning about yourself and others, downtime was filled with interacting with others and the group.”

3.2.3. Perceived Credible Facilitators—Peer Support

146-46 “What it has done for me, is it’s connected me with I think I have a bigger family now.”

135-45 “I’d say that was probably the most meaningful… to know you are not alone and you are not isolated, you are not different from everybody else. We all have different traumas, we are all at the same place in our lives.”

3.2.4. Experiential Learning—Learning How to “Do”

55-29 “I liked the experiential learning… like I like doing things and things with a message… [it] was very interesting because you could tell it was learning to let go but you experience it rather than just talking about it.”

105-39 “It’s the difference between somebody telling you, “oh you should let that go”, and actually having somebody walk you through the very process by which you then can let it go. Experiential learning is the best way to do it! Because then it takes it out of your head and gets it into your heart. It gets down in your emotional core so it’s not just a cognitive agreement.”

3.2.5. Holistic Approach—Integrating Spirituality

92-34 “I think one of the things to… the whole idea of spirituality instead of bringing religion in that was a good approach because most people aren’t religious in the military but the spiritual sense of it [the retreat] was really comforting and the exercises that we did whether it was being around the fire the first night and tossing away your inhibitions that in itself was just “ok we are starting to break a barrier” and I can see where we are going with this.”

120-42 “It’s a more holistic approach, you are kind of dealing with the whole body and the mind at the same time. So for me, that was far more effective.”

3.2.6. Putting Down and Letting Go

120-42 “Also you are not sitting on the couch across from a health care professional talking about things. [The program] gets you to actually do things so you know throwing rocks in the fire that you wrote a phrase on or going for a walk, walking the labyrinth umm… making a safe jump from a platform, going canoeing or even drawing and there’s music as well. All of that stuff, it’s a more holistic approach, you are kind of dealing with the whole body and the mind at the same time. So for me, that was far more effective.”

49-28 “Just opening up and facing the things that have been bothering me for so long, getting those things out there and realizing that other people are experiencing the same things, talking and learning different ways to deal with it, and better understand what’s going on.”

3.2.7. Forward Focus—Reconnecting to Self

75-32 “It really gives us a hope for the future and a reason to want to live, and to continue on and to know that we are not alone and there are a lot of traumatized people out there and we can work together and help each other.”

95-35 “I guess with [the program], what I came away from it was this healing journey is my journey and it is different of everyone else and I really took ownership of it when I left there and went “it’s no one else’s job to make me better, it’s mine.”

3.3. Outcomes

3.3.1. Re-Finding Self

7-23 “ Yeah it’s almost like I came home and I realized that I’ve got more self-worth and things that I was tolerating weren’t kind of facilitating how I felt about myself.”

28-25 “It was like a key opened a few doors because with this, I feel like you get into this negative reinforcement cycle and how you view yourself. And that is hard to get out of by yourself. And even though I look back and think yeah I have come a long way but there were still some fundamental questions that I couldn’t move forward on.”

3.3.2. Symptom Management through Self-Efficacy

26-25 “I’m a little more conscious of that point where I feel like I’m sliding down that slope and I can sort of catch myself most times and stop, preventing my mind from going in a darker spot than I would have before.”

75-32 “I am realizing I do have those symptoms which I hadn’t been so aware of, and now I am starting to be more aware of it. Not so much they decrease, but I am more aware. And now I am looking ok, so in this situation, what can I do to calm down. I can do deep breathing, think about something else, but I am starting to say that it is me being anxious, that I am being afraid, that I am being wary.”

3.3.3. Social Reconnection

53-29 “I have reconnected with my children in a very honest way and also have left behind a lot of judgment and resentment. I feel our relationships are stronger now.”

111-40 “I have identified with other people, I have connected with other people, I am not alone, I don’t need to be alone, my armor has come off. And my armor served a very specific and necessary purpose for a very long period of time, to keep things out. But for the last, probably 10 years or so, the armor has unfortunately kept things from getting out if that makes sense.”

3.3.4. Hope for a Meaningful Life

24-25 “I was wondering if I would ever get back to wearing the uniform again or even being a member (of the CAF) at all… and I mean now they reinforce that just because things didn’t happen doesn’t mean they get to… like define who I am kind of thing. Knowing this really helped to really break free from those sorts of thoughts.”

9-23 “I’ve been told that I am more relaxed, I don’t worry about the future, I’m not too concerned about the future, it will just kind of unfold, I just enjoy my time with my family and my friends so I just try to live in the moment with them.”

3.4. Gendered Analysis

3.4.1. Limiting “The Invasion”

54-29 “To me it was like an invasion... okay... and all these men came in and they invaded our private little group.”... “I am angry because the old school guys that invaded our cohort on Wednesday and I’m angry and resentful because an outsider came in and shared his story with the group and I don’t even know who this guy is, they haven’t introduced him to us and I haven’t had a chance to share my story.”

13-23 “And the other guy they had staying there (…), he was bothersome to me and maybe it was just me but he made a sexist comment right at the end at the very last hour of that thing.”

3.4.2. Creating Gender-Specific Programming

7-23 “I find that I put more emphasis on looking after myself, on that self-care component. Like I’ve continued doing the meditations on a daily basis, I’ve made a point of increasing my physical activity and those are things that were emphasized.”

154-47 “I think the idea of it is especially for women. You get away! You are not looking after your kids, you are not looking after anyone else, especially for women that are getting away, the residential portion is key!”

51-29 “For me... it makes a huge difference, because the guilt of being sexually assaulted and thinking it was my fault has been left there. The anger, the anger toward the system has been left there, the shame of being assaulted has been left there, and the shame of having my childhood traumas are left there.”

3.4.3. Addressing Group Dynamics

11-23 “Was going from an environment where everything is taken care of for you and you know you’re safe. And all the sudden you’re sent out to the airport to fly home. That was hard. I wish in a way that the program... maybe stay a little bit longer where we were before we were reintegrated into the human world. Honestly, it felt like my release from the military again.”

50-29 “There were a couple people there that I thought were a little more needy, in light it needed something a little more personally designed for them.”

3.4.4. Psychological Protection and Safety

54-29 “I really think that there should be a psychologist or psychiatrist involved in… I’m not saying the entire program, but when people are unloading, unpacking, disclosing you know serious trauma, I think if someone says something if they say the wrong thing... so she tried to use one of her stories and compare it to my story when it’s like comparing apples and oranges.”

146-46 “So I had to be very mindful of protecting myself from some of the stories that I heard from the other participants and because I know what it can do to my brain if I go into victim mode or if I go into, you know that one time, then all of a sudden there is an inflammatory response or a flare up as I said so that was my biggest concern going into this and some people they ripped open old wounds.”

4. Discussion

4.1. Cautions and Considerations

4.2. Learnings and Recommendations

- Intensive treatments for PTSD that may be an effective way to treat severe PTSD and MI where patients may need more time than current models of one-hour psychotherapeutic appointments per week.

- Trauma-oriented retreats may be beneficial as a complimentary modality to first- and second-level evidence-based treatments.

- Current evidence-based treatments may benefit from incorporating experiential learning opportunities where clients have the opportunities to practice skills with clinical supervision.

- The use of holistic activities, including spiritual ceremonies and rituals, may be beneficial for the healing for MI.

- Peer support, may be an under-used resource that may improve engagement in treatments and also address issues of social isolation.

- Sensitivity to gender considerations and the impact of sexual trauma (especially occupational sexual trauma) is needed in trauma-oriented retreats and all PTSD treatments.

- PTSD treatments may need to support the person to re-establish a forward-focused identity and quality of life mindset that extends beyond their pathology.

- Models of intensive outpatient care used for other mental health conditions may be beneficial to guiding PTSD treatments.

- More robust and rigorous research that includes longitudinal methodologies is needed to explore the efficacy of trauma-oriented retreats.

- Standardization or manualization of trauma-oriented retreats is needed to address variation in the qualifications and experiences of personnel, length of intervention, evidence-based merit, effectiveness and efficacy.

- Exploration using RE or similar methods to continue to answer the question of for whom, when, where, and how trauma-oriented retreats may be beneficial.

4.3. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sweet, J.; Poirier, A.; Pound, T.; Van Til, L.D. Well-Being of Canadian Regular Force Veterans, Findings from LASS 2019 Survey; Research Directorate Technical Report; Veterans Affairs Canada: Charlottetown, PE, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Carleton, R.N.; Afifi, T.O.; Turner, S.; Taillieu, T.; Duranceau, S.; LeBouthillier, D.M.; Sareen, J.; Ricciardelli, R.; Macphee, R.S.; Groll, D.; et al. Mental Disorder Symptoms among Public Safety Personnel in Canada. Can. J. Psychiatry 2018, 63, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Litz, B.T.; Stein, N.; Delaney, E.; Lebowitz, L.; Nash, W.P.; Silva, C.; Maguen, S. Moral injury and moral repair in war veterans: A preliminary model and intervention strategy. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2009, 29, 695–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farnsworth, J.; Drescher, K.D.; Evans, W.; Walser, R.D. A functional approach to understanding and treating military-related moral injury. J. Context. Behav. Sci. 2017, 6, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ames, D.; Erickson, Z.; Youssef, N.; Arnold, I.; Adamson, C.S.; Sones, A.C.; Yin, J.; Haynes, K.; Volk, F.; Teng, E.J.; et al. Moral Injury, Religiosity, and Suicide Risk in U.S. Veterans and Active Duty Military with PTSD Symptoms. Mil. Med. 2018, 184, e271–e278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Koenig, H.G. Measuring Symptoms of Moral Injury in Veterans and Active Duty Military with PTSD. Religions 2018, 9, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, S.H.; Schneider, S.M.; Kravitz, L.; Mermier, C.; Burge, M.R. Mind-body practices for posttraumatic stress disorder. J. Investig. Med. 2013, 61, 827–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artra, I.P. Transparent Assessment: Discovering Authentic Meanings Made by Combat Veterans. J. Constr. Psychol. 2014, 27, 211–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, E.; Wood, D.S.; Usadi, E.J.; Applegarth, D.M. TRR’s Warrior Camp: An Intensive Treatment Program for Combat Trauma in Active Military and Veterans of All Eras. Mil. Med. 2018, 183, 403–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dahlgren, S.; Martinez, M.; Méte, M.; Dutton, M.A. Healing narratives from the Holistic Healing Arts Retreat. Traumatology 2020, 26, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, K.H.; McDaniel, J.T.; Albright, D.L.; Fletcher, K.L.; Koenig, H.G. Spiritual Fitness for Military Veterans: A Curriculum Review and Impact Evaluation Using the Duke Religion Index (DUREL). J. Relig. Health 2018, 57, 1168–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutton, M.A.; Dahlgren, S.; Franco-Rahman, M.; Martinez, M.; Serrano, A.; Mete, M. A holistic healing arts model for counselors, advocates, and lawyers serving trauma survivors: Joyful Heart Foundation Retreat. Traumatology 2017, 23, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vella, E.J.; Milligan, B.; Bennett, J.L. Participation in Outdoor Recreation Program Predicts Improved Psychosocial Well-Being Among Veterans with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: A Pilot Study. Mil. Med. 2013, 178, 254–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ward, K.P.; Wood, D.S.; Young, T.M. Retreat Intervention Effectiveness for Female Survivors of Child Sexual Abuse. Res. Soc. Work Pract. 2020, 30, 760–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hara, C. Introduction to Military and Veteran Retreats. In Combat Stress; The American Institute of Stress: Weatherford, TX, USA, 2017; Volume 6, pp. 4–6. [Google Scholar]

- Kamena, M.; Galvez, H. Intensive Residential Treatment Program: Efficacy for Emergency Responders Critical Incident Stress. J. Police Crim. Psychol. 2020, 35, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.P.-M.; Jelinek, G.A.; Weiland, T.J.; MacKinlay, C.A.; Dye, S.; Gawler, I. Effect of a residential retreat promoting lifestyle modifications on health-related quality of life in people with multiple sclerosis. Qual. Prim. Care 2010, 18, 379–389. [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzaki, K.; Taniguchi, S.; Inoue, K.; Kawamura, T. Effectiveness of a healthcare retreat for male employees with cardiovascular risk factors. Prev. Med. Rep. 2018, 13, 170–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monk, J.K.; Ogolsky, B.G.; Bruner, V. Veteran Couples Integrative Intensive Retreat Model: An Intervention for Military Veterans and Their Relational Partners. J. Couple Relatsh. Ther. 2016, 15, 158–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pawson, R.; Tilley, N. Realistic Evaluation; Sage Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Jagosh, J. Realist Synthesis for Public Health: Building an Ontologically Deep Understanding of How Programs Work, For Whom, and In Which Contexts. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2019, 40, 361–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pawson, R.; Greenhalgh, T.; Harvey, G.; Walshe, K. Realist review—A new method of systematic review designed for complex policy interventions. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 2005, 10, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terry, G.; Hayfield, N.; Clarke, V.; Braun, V. Thematic analysis. In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research in Psychology; Willig, C., Stainton Rogers, W., Eds.; Sage Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017; Volume 2, pp. 17–37. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln, Y.S.; Guba, E.G. Naturalistic Inquiry; Sage Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Pawson, R. Evidence-based Policy: The Promise of ‘Realist Synthesis’. Evaluation 2002, 8, 340–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hoge, C.W.; Castro, C.A.; Messer, S.C.; McGurk, D.; Cotting, D.I.; Koffman, R.L. Combat Duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, Mental Health Problems, and Barriers to Care. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 351, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hoge, C.W.; Auchterlonie, J.L.; Milliken, C.S. Mental Health Problems, Use of Mental Health Services, and Attrition from Military Service After Returning from Deployment to Iraq or Afghanistan. JAMA 2006, 295, 1023–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kim, P.Y.; Thomas, J.L.; Wilk, J.E.; Castro, C.A.; Hoge, C.W. Stigma, Barriers to Care, and Use of Mental Health Services Among Active Duty and National Guard Soldiers After Combat. Psychiatr. Serv. 2010, 61, 582–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steenkamp, M.M.; Litz, B.; Hoge, C.W.; Marmar, C.R. Psychotherapy for Military-Related PTSD. JAMA 2015, 314, 489–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerger, H.; Munder, T.; Barth, J. Specific and Nonspecific Psychological Interventions for PTSD Symptoms: A Meta-Analysis with Problem Complexity as a Moderator. J. Clin. Psychol. 2014, 70, 601–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendriks, L.; De Kleine, R.A.; Broekman, T.; Hendriks, G.-J.; Van Minnen, A. Intensive prolonged exposure therapy for chronic PTSD patients following multiple trauma and multiple treatment attempts. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2018, 9, 1425574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hurley, E.C. Effective Treatment of Veterans With PTSD: Comparison Between Intensive Daily and Weekly EMDR Approaches. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez, M.Z.; Nijdam, M.J.; Ter Heide, F.J.J.; Van Der Aa, N.; Olff, M. A five-day inpatient EMDR treatment programme for PTSD: Pilot study. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2018, 9, 1425575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Held, P.; Zalta, A.K.; Smith, D.L.; Bagley, J.M.; Steigerwald, V.L.; Boley, R.A.; Miller, M.; Brennan, M.B.; Van Horn, R.; Pollack, M.H. Maintenance of treatment gains up to 12-months following a three-week cognitive processing therapy-based intensive PTSD treatment programme for veterans. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2020, 11, 1789324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Held, P.; Klassen, B.J.; Coleman, J.A.; Thompson, K.; Rydberg, T.S.; Van Horn, R. Delivering Intensive PTSD Treatment Virtually: The Development of a 2-Week Intensive Cognitive Processing Therapy Based Program in Response to COVID-19. Cogn. Behav. Pract. 2021, 28, 543–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toukolehto, O.T.; Waits, W.M.; Preece, D.M.; Samsey, K.M. Accelerated Resolution Therapy-Based Intervention in the Treatment of Acute Stress Reactions During Deployed Military Operations. Mil. Med. 2019, 185, 356–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kip, K.E.; Grant, D.; Hernandez, D.F.; Girling, S.A.; Ashforth, J.; Brown, A. Program evaluation of the Lone Survivor Foundation (LSF) retreat model for veterans and family members with symptoms of psychological trauma. Combat Stress 2017, 6, 29–40. [Google Scholar]

- Raudales, A.M.; Preston, T.J.; Albanese, B.J.; Schmidt, N.B. Emotion dysregulation as a maintenance factor for posttraumatic stress symptoms: The role of anxiety sensitivity. J. Clin. Psychol. 2020, 76, 2183–2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spies, J.P.; Cwik, J.C.; Willmund, G.D.; Knaevelsrud, C.; Schumacher, S.; Niemeyer, H.; Engel, S.; Küster, A.; Muschalla, B.; Köhler, K.; et al. Associations Between Difficulties in Emotion Regulation and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in Deployed Service Members of the German Armed Forces. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 576553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christ, N.M.; Elhai, J.D.; Forbes, C.N.; Gratz, K.L.; Tull, M.T. A machine learning approach to modeling PTSD and difficulties in emotion regulation. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 297, 113712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roemer, L.; Litz, B.; Orsillo, S.; Wagner, A.W. A preliminary investigation of the role of strategic withholding of emotions in PTSD. J. Trauma. Stress 2001, 14, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farnsworth, J.K.; Drescher, K.D.; Nieuwsma, J.A.; Walser, R.B.; Currier, J.M. The Role of Moral Emotions in Military Trauma: Implications for the Study and Treatment of Moral Injury. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2014, 18, 249–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tang, E.; Jones, C.; Smith-MacDonald, L.; Brown, M.R.; Vermetten, E.H.; Brémault-Phillips, S. Decreased emotional dysregulation following multi-modal motion-assisted memory desensitization and reconsolidation therapy (3MDR): Identifying possible driving factors in remediation of treatment-resistant PTSD. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12243. [Google Scholar]

- Sciarrino, N.A.; Warnecke, A.J.; Teng, E.J. A Systematic Review of Intensive Empirically Supported Treatments for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. J. Trauma. Stress 2020, 33, 443–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagenfeld, A.; Roy-Fisher, C.; Mitchell, C. Collaborative design: Outdoor environments for veterans with PTSD. Facilities 2013, 31, 391–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lackey, N.Q.; Tysor, D.A.; McNay, G.D.; Joyner, L.; Baker, K.H.; Hodge, C. Mental health benefits of nature-based recreation: A systematic review. Ann. Leis. Res. 2021, 24, 379–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulsen, D.V.; Stigsdotter, U.K.; Djernis, D.; Sidenius, U. Everything just seems much more right in nature. How veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder experience nature-based activities in a forest therapy garden. Health Psychol. Open 2016, 3, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Poulsen, D.V. Nature-based therapy as a treatment for veterans with PTSD: What do we know? J. Public Ment. Health 2017, 16, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atuel, H.R.; Castro, C.A. Military Cultural Competence. Clin. Soc. Work J. 2018, 46, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currier, J.M.; McCormick, W.H.; Carroll, T.D.; Sims, B.M.; Isaak, S.L. Prospective Patterns of Help-Seeking Behavior Among Military Veterans with Probable Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Major Depressive Disorder. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2018, 206, 950–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porcari, C.; Koch, E.I.; Rauch, S.A.M.; Hoodin, F.; Ellison, G.; McSweeney, L. Predictors of Help-Seeking Intentions in Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom Veterans and Service Members. Mil. Med. 2017, 182, e1640–e1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Holliday, R.; Smith, N.B.; Holder, N.; Gross, G.M.; Monteith, L.L.; Maguen, S.; Hoff, R.A.; Harpaz-Rotem, I. Comparing the effectiveness of VA residential PTSD treatment for veterans who do and do not report a history of MST: A national investigation. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2020, 122, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hundt, N.E.; Robinson, A.; Arney, J.; Stanley, M.A.; Cully, J.A. Veterans’ Perspectives on Benefits and Drawbacks of Peer Support for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Mil. Med. 2015, 180, 851–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jain, S.; McLean, C.; Adler, E.P.; Rosen, C.S. Peer Support and Outcome for Veterans with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in a Residential Rehabilitation Program. Community Ment. Health J. 2016, 52, 1089–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith-MacDonald, L.; Norris, J.; Raffin-Bouchal, S.; Sinclair, S. Spirituality and Mental Well-Being in Combat Veterans: A Systematic Review. Mil. Med. 2017, 182, e1920–e1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nash, W.P. Identity and Imagination in Moral Injury and Moral Repair; Canadian Institute for Military and Veteran Health Research: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Brémault-Phillips, S.; Pike, A.; Scarcella, F.; Cherwick, T. Spirituality and Moral Injury Among Military Personnel: A Mini-Review. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brock, R.N.; Lettini, G. Soul Repair: Recovering from Moral Injury after War; Beacon Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Doehring, C. Military Moral Injury: An Evidence-Based and Intercultural Approach to Spiritual Care. Pastor. Psychol. 2018, 68, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawson, S. Sustaining Lamentation for Military Moral Injury: Witness Poetry that Bears the Traces of Extremity. Pastor. Psychol. 2018, 68, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebert, E.A. Accessible Spiritual Practices to Aid in Recovery from Moral Injury. Pastor. Psychol. 2018, 68, 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Smith-MacDonald, L.; VanderLaan, A.; Kaneva, Z.; Voth, M.; Pike, A.; Jones, C.; Bremault-Phillips, S. “Putting Down and Letting Go”: An Exploration of a Community-Based Trauma-Oriented Retreat Program for Military Personnel, Veterans, and RCMP. Trauma Care 2022, 2, 95-113. https://doi.org/10.3390/traumacare2020009

Smith-MacDonald L, VanderLaan A, Kaneva Z, Voth M, Pike A, Jones C, Bremault-Phillips S. “Putting Down and Letting Go”: An Exploration of a Community-Based Trauma-Oriented Retreat Program for Military Personnel, Veterans, and RCMP. Trauma Care. 2022; 2(2):95-113. https://doi.org/10.3390/traumacare2020009

Chicago/Turabian StyleSmith-MacDonald, Lorraine, Annelies VanderLaan, Zornitsa Kaneva, Melissa Voth, Ashley Pike, Chelsea Jones, and Suzette Bremault-Phillips. 2022. "“Putting Down and Letting Go”: An Exploration of a Community-Based Trauma-Oriented Retreat Program for Military Personnel, Veterans, and RCMP" Trauma Care 2, no. 2: 95-113. https://doi.org/10.3390/traumacare2020009