Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Their Derivatives: Old Problems and New Possibilities in Regenerative Medicine for Neurological Diseases

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Clinical Studies on the Application of MSCs

2.1. Stroke

2.2. Multiple Sclerosis

2.3. Spinal Cord Injury

2.4. Alzheimer’s Disease

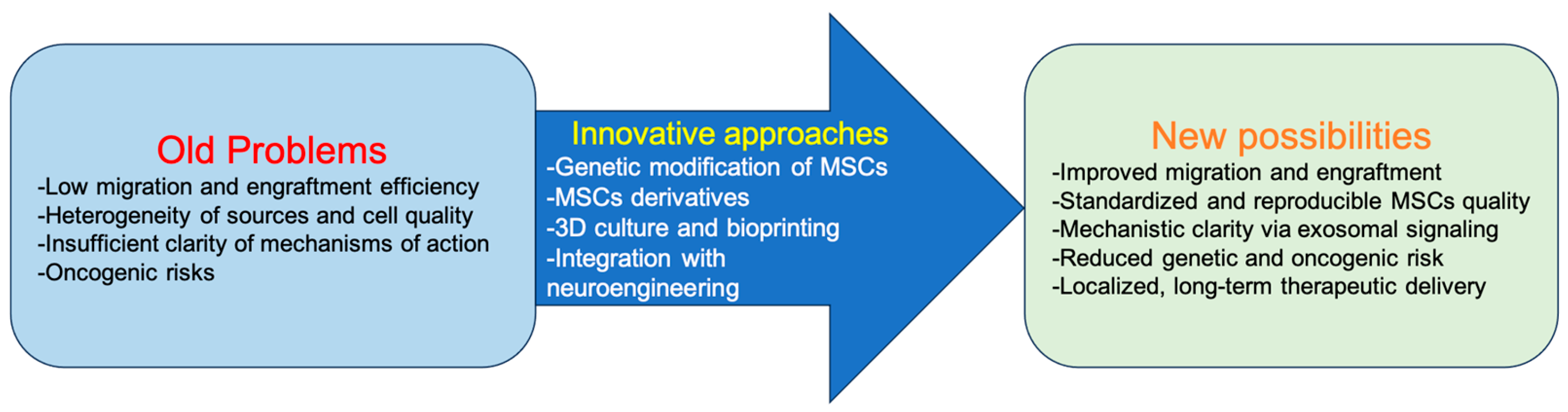

3. Old Problems and Challenges

- (1)

- Low efficiency of migration and engraftment. One of the main obstacles remains the low survival and limited migration of MSCs. In nonhuman primates, after intravenous administration, the efficiency of MSC engraftment into various tissues is extremely low, ranging from 0.1 to 2.7% [17]. The homing of culture-expanded MSCs is ineffective compared to leukocytes and hematopoietic stem cells, which is apparently due to the absence of the corresponding adhesion receptors and chemokines; however, there are engineering strategies that can enhance homing [18]. Such strategies include genetic modification, cell surface engineering, MSC priming in vitro, and, in particular, ultrasound-based methods [19].

- (2)

- Heterogeneity of sources and cell quality. A key problem remains the variability of MSC characteristics, which depends on donor age, method of isolation, culture conditions, and the selected tissue source (bone marrow, adipose tissue, umbilical cord blood) [20]. It is known that with donor age, the proliferative potential and differentiation capacity of MSCs decrease [21,22], which is critical for neuroregeneration.

- (3)

- Insufficient clarity of mechanisms of action. Systemically administered MSCs are often detected in significant concentrations in the bone marrow compartment, as well as in the area of injury or inflammation, and these cells have the potential to reduce inflammation and stimulate tissue regeneration [18]. Although MSCs demonstrate positive effects in neuroregeneration, the question remains unresolved: do they act as a source for replacing missing cells, or is their key role immunomodulation and support of the regenerative niche through the secretion of growth factors and exosomes? Current data suggest that the main effect is associated with paracrine action rather than direct integration of MSCs into damaged tissues [23].

- (4)

- Oncogenic risks. Finally, there is a risk of adverse side effects associated with MSC transplantation. In the study by Jeong et al., 2016, in a mouse model of experimental myocardial infarction and diabetic neuropathy, transplantation of BM-MSCs led to sarcoma development in 30–50% of animals; histology indicated malignant tumors of muscle origin. Chromosomal analysis revealed multiple chromosomal aberrations in the injected MSCs [24]. In another study, the possibility of MSC malignancy under the influence of the tumor microenvironment was experimentally demonstrated. EGFP-labeled BM-MSCs were transplanted into immunodeficient mice via tail vein, while glioma stem-like cells (GSCs) were injected into the skull region of the same animals. After tumor formation, MSCs were isolated from tumor tissue and analyzed. Transplanted MSCs exhibited signs of transformation: overexpression of Telomerase Reverse Transcriptase (TERT), high proliferation rate, colony-forming ability in vitro, and pronounced malignant behavior in vivo—upon re-transplantation, tumors developed in 100% of recipients [25]. The authors concluded that MSC malignancy was induced by the tumor microenvironment associated with GSCs and accompanied by TERT activation, which may represent a potential oncogenic risk in the clinical use of MSCs, especially in the context of tumor diseases. This approach necessitates strict clinical selection of patients with clearly established exclusion criteria, including mandatory verification of the absence of oncological conditions.

4. New Possibilities and Approaches

- MSCs derivatives. Over the past decade, research focus has shifted from MSCs themselves to their derivatives—exosomes, microvesicles, and secretomes. These components facilitate intercellular communication, stimulate tissue regeneration, and reduce inflammation. MSC-derived exosomes have attracted the greatest attention due to their ability to cross the blood–brain barrier, low immunogenicity, and feasibility of standardized large-scale production [5,26,27,28]. Experimental studies in models of stroke, spinal cord and brain injury, and Parkinson’s disease have demonstrated that MSC exosomes reduce neuroinflammation, improve tissue repair, and promote functional recovery [7,29,30,31].

- Genetic modification of MSCs. Genetic engineering provides opportunities to enhance the therapeutic potential of MSCs. Introduction of constructs via CRISPR/Cas9, lentiviruses, or AAV vectors enables targeted upregulation of neurotrophic factors (Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF), Glial cell line-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (GDNF), Nerve Growth Factor (NGF)), anti-inflammatory molecules (IL-10), or chemotaxis receptors (CXCR4)), thereby improving homing and engraftment [4,16,32,33]. Such modified MSCs show improved survival in the hostile microenvironment of the CNS and more efficient migration to injury sites [34,35]. Furthermore, the creation of regulatory MSC lines that induce therapeutic gene expression in response to microenvironmental signals (e.g., hypoxia or inflammation) represents a promising direction in genetic engineering. Selich et al. (2023) successfully developed the ECA7 promoter, which is activated by IFN-γ and induces IL-10 secretion in a mouse model of acute allergic syndrome. This approach could potentially be applied to a wide spectrum of pathological conditions [36].

- 3D culture and bioprinting. The transition from 2D cultures to three-dimensional systems, including spheroids, organoids, and bioprinted constructs, has enabled more accurate modeling of the microenvironment of damaged neural tissue in vitro [37]. These 3D systems enhance MSC secretion, interaction with the extracellular matrix, and resistance to stress conditions [38]. Moreover, bioprinting allows for the creation of patient-specific matrices incorporating MSCs, paving the way toward personalized regenerative medicine [39,40].

- Integration with neuroengineering. The use of biocompatible materials—including hydrogels, nanofibers, and magnetic or conductive nanostructures—as carriers for MSCs and their derivatives enables localized delivery, prolonged therapeutic action, and protection from cell death. For example, encapsulation of MSCs in alginate- or collagen-based matrices enhances their survival and preserves functional activity after transplantation [41,42]. The use of magnetically guided systems and nanotechnologies is also being actively explored for targeted delivery of MSCs to lesion sites [43,44].

5. Clinical Studies on the Application of MSC-Derived Exosomes

6. Gene Modification of MSCs

6.1. CRISPR/Cas9

6.2. Virus-Mediated Modification

6.3. Adeno-Associated Viruses (AAVs)

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AAVs | Adeno-associated viruses |

| ADAS-Cog scale | Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive Subscale |

| AIS | Abbreviated Injury Scale |

| BDNF | Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor |

| CNTF | Ciliary Neurotrophic Factor |

| GSGs | Glioma Stem-like Cells |

| GDNF | Glial Cell Line-Derived Neurotrophic Factor |

| IDO-1 | Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1 |

| KLF7 | Kruppel-like factor 7 |

| LV | Lentiviruses |

| MoCA-B scale | Montreal Cognitive Assessment-Basic |

| MSC-NP | Mesenchymal stem cell-derived neural progenitors |

| NGF | Nerve growth factor |

| PGE2 | Prostaglandin E2 |

| SCI | Spinal Cord Injury |

| sRAGE | Soluble Receptor for Advanced Glycation End-products |

| TERT | Telomerase Reverse Transcriptase |

References

- Galieva, L.R.; James, V.; Mukhamedshina, Y.O.; Rizvanov, A.A. Therapeutic potential of extracellular vesicles for the treatment of nerve disorders. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzas, E.I. The roles of extracellular vesicles in the immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2023, 23, 236–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafarinia, M.; Farrokhi, M.R.; Ganjalikhani Hakemi, M.; Cho, W.C. The role of miRNAs from mesenchymal stem/stromal cells-derived extracellular vesicles in neurological disorders. Hum. Cell 2023, 36, 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Yang, J.; Yan, W.; Li, Y.; Shen, Z.; Asahara, T. Pretreatment of cardiac stem cells with exosomes derived from mesenchymal stem cells enhances myocardial repair. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2016, 5, e002856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, L.; Cai, Y.; Geng, Y.; Yao, X.; Wang, L.; Cao, H.; Zhang, X.; Wu, Q.; Kong, D.; Ding, D.; et al. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles attenuate tPA-induced blood–brain barrier disruption in murine ischemic stroke models. Acta Biomater. 2022, 154, 424–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Li, Y.; Ji, W.; Zhao, R.; Lu, Z.; Shen, J.; Wu, Y.; Wang, J.; Hao, Q.; Wang, J.; et al. Intranasal administration of self-oriented nanocarriers based on therapeutic exosomes for synergistic treatment of Parkinson’s disease. ACS Nano 2022, 16, 869–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Dong, X.; Tian, M.; Liu, C.; Wang, K.; Li, L.; Liu, Z.; Liu, J. Stem cell-based therapies for ischemic stroke: A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2020, 11, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, J.W.; Chang, W.H.; Bang, O.Y.; Moon, G.J.; Kim, S.J.; Kim, S.K.; Lee, J.S.; Sohn, S.I.; Kim, Y.H.; Starting-2 Collaborators. Efficacy and safety of intravenous mesenchymal stem cells for ischemic stroke. Neurology 2021, 96, e1012–e1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.A.; Alam, S.S.; Kundu, S.; Ahmed, S.; Sultana, S.; Patar, A.; Hossan, T. Mesenchymal stem cell therapy in multiple sclerosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 6311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, V.K.; Stark, J.; Williams, A.; Roche, M.; Malin, M.; Kumar, A.; Carlson, A.L.; Kizilbash, C.; Wollowitz, J.; Andy, C.; et al. Efficacy of intrathecal mesenchymal stem cell-neural progenitor therapy in progressive MS: Results from a phase II, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2024, 15, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bang, O.Y.; Lee, J.S.; Lee, P.H.; Lee, G. Autologous mesenchymal stem cell transplantation in stroke patients. Ann. Neurol. 2005, 57, 874–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, M.L.; Crawford, J.R.; Dib, N.; Verkh, L.; Tankovich, N.; Cramer, S.C. Phase I/II study of safety and preliminary efficacy of intravenous allogeneic mesenchymal stem cells in chronic stroke. Stroke 2019, 50, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macêdo, C.T.; de Freitas Souza, B.S.; Villarreal, C.F.; Silva, D.N.; da Silva, K.N.; de Souza, C.L.E.M.; da Silva Paixão, D.; da Rocha Bezerra, M.; da Silva Moura Costa, A.O.; Brazão, E.S.; et al. Transplantation of autologous mesenchymal stromal cells in complete cervical spinal cord injury: A pilot study. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1451297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bydon, M.; Qu, W.; Moinuddin, F.M.; Hunt, C.L.; Garlanger, K.L.; Reeves, R.K.; Windebank, A.J.; Zhao, K.D.; Jarrah, R.; Trammell, B.C.; et al. Intrathecal delivery of adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells in traumatic spinal cord injury: Phase I trial. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 2201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Cho, K.R.; Jang, H.; Lee, N.K.; Jung, Y.H.; Kim, J.P.; Lee, J.I.; Chang, J.W.; Park, S.; Kim, S.T.; et al. Intracerebroventricular injection of human umbilical cord blood mesenchymal stem cells in patients with Alzheimer’s disease dementia: A phase I clinical trial. Alzheimer’s Res. Ther. 2021, 13, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirshblum, S.; Snider, B.; Eren, F.; Guest, J. Characterizing natural recovery after traumatic spinal cord injury. J. Neurotrauma 2021, 38, 1267–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devine, S.M.; Cobbs, C.; Jennings, M.; Bartholomew, A.; Hoffman, R. Mesenchymal stem cells distribute to a wide range of tissues following systemic infusion into nonhuman primates. Blood 2003, 101, 2999–3001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karp, J.M.; Teo, G.S.L. Mesenchymal stem cell homing: The devil is in the details. Cell Stem Cell 2009, 4, 206–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, M.; Liu, D.D.; Thakor, A.S. Mesenchymal stromal cell homing: Mechanisms and strategies for improvement. iScience 2019, 15, 421–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Liang, B.; Xu, J. Unveiling heterogeneity in MSCs: Exploring marker-based strategies for defining MSC subpopulations. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaim, M.; Karaman, S.; Cetin, G.; Isik, S. Donor age and long-term culture affect differentiation and proliferation of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Ann. Hematol. 2012, 91, 1175–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhery, M.S.; Badowski, M.; Muise, A.; Pierce, J.; Harris, D.T. Donor age negatively impacts adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cell expansion and differentiation. J. Transl. Med. 2014, 12, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spees, J.L.; Lee, R.H.; Gregory, C.A. Mechanisms of mesenchymal stem/stromal cell function. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2016, 7, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.O.; Han, J.W.; Kim, J.M.; Cho, H.J.; Park, C.; Lee, N.; Kim, D.W.; Yoon, Y.S. Malignant tumor formation after transplantation of short-term cultured bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells in experimental myocardial infarction and diabetic neuropathy. Circ. Res. 2011, 108, 1340–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Chen, J.; Dai, X.; Cai, H.; Ji, X.; Sheng, Y.; Liu, H.; Yang, L.; Chen, Y.; Xi, D.; et al. Human glioma stem-like cells induce malignant transformation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells by activating TERT expression. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 104418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kink, J.A.; Bellio, M.A.; Forsberg, M.H.; Lobo, A.; Thickens, A.S.; Lewis, B.M.; Ong, I.M.; Khan, A.; Capitini, C.M.; Hematti, P. Large-scale bioreactor production of extracellular vesicles from mesenchymal stromal cells for treatment of acute radiation syndrome. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2024, 15, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.C.; Hu, X.M.; Long, Y.F.; Huang, H.R.; He, Y.; Xu, Z.R.; Qi, Z.Q. Treatment of Parkinson’s disease model with human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes loaded with BDNF. Life Sci. 2024, 356, 123014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Hu, X.; Liu, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Jiang, P.; Lin, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Li, L.C.; Qi, Z. Immunological safety evaluation of exosomes derived from human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells in mice. Stem Cells Int. 2025, 2025, 9986368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Y.; Seyfried, D.; Meng, Y.; Yang, D.; Schultz, L.; Chopp, M.; Seyfried, D. Multipotent mesenchymal stromal cell–derived exosomes improve functional recovery after experimental intracerebral hemorrhage in the rat. J. Neurosurg. 2018, 131, 290–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kostennikov, A.; Kabdesh, I.; Sabirov, D.; Timofeeva, A.; Rogozhin, A.; Shulman, I.; Rizvanov, A.; Mukhamedshina, Y. A comparative study of mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles’ local and systemic dose-dependent administration in rat spinal cord injury. Biology 2022, 11, 1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Chen, Z.J.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Shen, M.P.; Zhao, B.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Lei, J.G.; Ren, C.J.; Chang, J.; et al. Manufacturing, quality control, and GLP-grade preclinical study of nebulized allogenic adipose mesenchymal stromal cells-derived extracellular vesicles. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2024, 15, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Kim, D.I.; Kim, E.K.; Kim, C.W. CXCR4 overexpression in human adipose tissue-derived stem cells improves homing and engraftment in an animal limb ischemia model. Cell Transplant. 2017, 26, 191–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peruzzaro, S.T.; Andrews, M.M.M.; Al-Gharaibeh, A.; Pupiec, O.; Resk, M.; Story, D.; Maiti, P.; Rossignol, J.; Dunbar, G.L. Transplantation of mesenchymal stem cells genetically engineered to overexpress interleukin-10 promotes alternative inflammatory response in rat model of traumatic brain injury. J. Neuroinflammation 2019, 16, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, H.; He, Y.; Xiong, W.; Jing, S.; Duan, X.; Huang, Z.; Nahal, G.S.; Peng, Y.; Li, M.; Zhu, Y.; et al. MSC based gene delivery methods and strategies improve the therapeutic efficacy of neurological diseases. Bioact. Mater. 2023, 23, 409–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, D.; Xu, Y.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, Q. Mesenchymal stem cell-macrophage crosstalk and maintenance of inflammatory microenvironment homeostasis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 681171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selich, A.; Fleischauer, J.; Roepke, T.; Weisskoeppel, L.; Galla, M.; von Kaisenberg, C.; Maus, U.A.; Schambach, A.; Rothe, M. Inflammation-inducible promoters to overexpress immune inhibitory factors by MSCs. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2023, 14, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orr, A.; Kalantarnia, F.; Nazir, S.; Bolandi, B.; Alderson, D.; O’Grady, K.; Hoorfar, M.; Julian, L.M.; Willerth, S.M. Recent advances in 3D bioprinted neural models: A systematic review on the applications to drug discovery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2025, 218, 115524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartosh, T.J.; Ylostalo, J.H. Efficacy of 3D culture priming is maintained in human mesenchymal stem cells after extensive expansion of the cells. Cells 2019, 8, 1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, S.V.; Atala, A. 3D bioprinting of tissues and organs. Nat. Biotechnol. 2014, 32, 773–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Yao, C.; Xu, Z.; Shang, G.; Peng, J.; Xie, H.; Qian, T.; Qiu, Z.; Maeso, L.; Mao, M.; et al. Recent advances in 3D models of the nervous system for neural regeneration research and drug development. Acta Biomater. 2025, 202, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leijs, M.; Villafuertes, E.; Haeck, J.; Koevoet, W.; Fernandez-Gutierrez, B.; Hoogduijn, M.; Verhaar, J.A.N.; Bernsen, M.; Buul, G.; van Osch, G. Encapsulation of allogeneic mesenchymal stem cells in alginate extends local presence and therapeutic function. Eur. Cells Mater. 2017, 33, 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San JoseLorena, H. Microfluidic encapsulation supports stem cell viability, proliferation, and neuronal differentiation. Tissue Eng. Part C Methods 2018, 24, 158–170. [Google Scholar]

- Vaněček, V.; Zablotskii, V.; Forostyak, S.; Růřička, J.; Herynek, V.; Babič, M.; Jendelová, P.; Kubinová, Š.; Dejneka, A.; Syková, E. Highly efficient magnetic targeting of mesenchymal stem cells in spinal cord injury. Int. J. Nanomed. 2012, 7, 3719–3730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moayeri, A.; Darvishi, M.; Amraei, M. Homing of super paramagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles (SPIONs) labeled adipose-derived stem cells by magnetic attraction in a rat model of Parkinson’s disease. Int. J. Nanomed. 2020, 15, 1297–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Song, Q.; Dai, C.; Cui, S.; Tang, R.; Li, S.; Chang, J.; Li, P.; Wang, J.; Li, J.; et al. Clinical safety and efficacy of allogenic human adipose mesenchymal stromal cells-derived exosomes in patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease: A phase I/II clinical trial. Gen. Psychiatry 2023, 36, e101143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhlaghpasand, M.; Tavanaei, R.; Hosseinpoor, M.; Yazdani, K.O.; Soleimani, A.; Zoshk, M.Y.; Soleimani, M.; Chamanara, M.; Ghorbani, M.; Deylami, M.; et al. Safety and potential effects of intrathecal injection of allogeneic human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes in complete subacute spinal cord injury: A first-in-human, single-arm, open-label, phase I clinical trial. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2024, 15, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebrahim, N.; James, V.; Rizvanov, A.A.; Mukhamedshina, Y. Genetic modification of mesenchymal stem cells for neurological disease therapy: What effects does it have on phenotype/cell behavior, determining their effectiveness? Mol. Diagn. Ther. 2020, 24, 683–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrzejewska, A.; Dabrowska, S.; Lukomska, B.; Janowski, M. Mesenchymal stem cells in neurological disorders. Adv. Sci. 2021, 8, 2002944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasiri, H.; Manoochehrabadi, T.; Eskandari, F.; Majidi, J.; Gholipourmalekabadi, M. Genetic modification of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs): Novel strategy to expand their naïve applications in critical illness. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2025, 52, 501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazrati, A.; Malekpour, K.; Soudi, S.; Hashemi, S.M. CRISPR/Cas9-engineered mesenchymal stromal/stem cells and their extracellular vesicles: A new approach to overcoming cell therapy limitations. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 156, 113943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Niu, H.; Zhao, Z.J.; Fu, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, F.; Zeng, L. CRISPR/Cas9 knockout of Bak mediates Bax translocation to mitochondria in response to TNFα/CHX-induced apoptosis. Biomed. Res. Int. 2019, 2019, 9071297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yu, T.; Qi, C. Generation of PTEN knockout bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell lines by CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing. Cytotechnology 2018, 70, 783–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.J.; Choi, B.; Kim, Y.; Lee, S.E.; Jin, H.J.; Lee, H.S.; Chang, E.J.; Kim, S.W. The upregulation of toll-like receptor 3 via autocrine IFN-β signaling drives the senescence of human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells through JAK1. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, A.R.; Shin, H.R.; Kwon, J.; Lee, S.B.; Lee, S.E.; Kim, E.Y.; Kweon, J.; Chang, E.J.; Kim, Y.; Kim, S.W. Highly efficient genome editing via CRISPR-Cas9 ribonucleoprotein (RNP) delivery in mesenchymal stem cells. BMB Rep. 2024, 57, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Wu, J.; Gu, W.; Huang, Y.; Tong, Z.; Huang, L.; Tan, J. Exosome–liposome hybrid nanoparticles deliver CRISPR/Cas9 system in MSCs. Adv. Sci. 2018, 5, 1700611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Chang, M.; Zhang, R.; Wo, J.; Wu, B.; Zhang, H.; Sun, G. Spinal cord injury target-immunotherapy with TNF-α autoregulated and feedback-controlled human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell derived exosomes remodelled by CRISPR/Cas9 plasmid. Biomater. Adv. 2022, 133, 112624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collon, K.; Gallo, M.C.; Bell, J.A.; Chang, S.W.; Rodman, J.C.S.; Sugiyama, O.; Kohn, D.B.; Lieberman, J.R. Improving lentiviral transduction of human adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Hum. Gene Ther. 2022, 33, 1260–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, F.; Tristán-Manzano, M.; Maldonado-Pérez, N.; Sánchez-Hernández, S.; Benabdellah, K.; Cobo, M. Stable genetic modification of mesenchymal stromal cells using lentiviral vectors. Methods Mol. Biol. 2019, 1937, 267–280. [Google Scholar]

- McGinley, L.; McMahon, J.; Strappe, P.; Barry, F.; Murphy, M.; O’Toole, D.; O’Brien, T. Lentiviral vector mediated modification of mesenchymal stem cells & enhanced survival in an in vitro model of ischaemia. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2011, 2, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Wu, D.; Zhang, R.; Shuang, W.; Sun, J.; Hao, H.; An, Q. Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells expressing the Shh transgene promotes functional recovery after spinal cord injury in rats. Neurosci. Lett. 2014, 573, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Chen, D.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, X.; Huang, Z.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z. Overexpression of CXCR4 in mesenchymal stem cells promotes migration, neuroprotection and angiogenesis in a rat model of stroke. J. Neurol. Sci. 2012, 316, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheper, V.; Schwieger, J.; Hamm, A.; Lenarz, T.; Hoffmann, A. BDNF-overexpressing human mesenchymal stem cells mediate increased neuronal protection in vitro. J. Neurosci. Res. 2019, 97, 1414–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, B.; Wu, X.; Wang, N.; Zhang, Y. Therapeutic efficacy of lentiviral vector mediated BDNF gene-modified MSCs in cerebral infarction. Sheng Wu Gong Cheng Xue Bao 2008, 24, 1174–1179. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, L.; Lin, Q.; Wang, P.; Yao, L.; Leong, K.; Tan, Z.; Huang, Z. Enhanced neuroprotective efficacy of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells co-overexpressing BDNF and VEGF in a rat model of cardiac arrest-induced global cerebral ischemia. Cell Death Dis. 2017, 8, e2774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zubkova, E.S.; Beloglazova, I.B.; Ratner, E.I.; Dyikanov, D.T.; Dergilev, K.V.; Menshikov, M.Y.; Parfyonova, Y.V. Transduction of rat and human adipose-tissue derived mesenchymal stromal cells by adeno-associated viral vector serotype DJ. Biol. Open 2021, 10, bio058461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakajima, M.; Nito, C.; Sowa, K.; Suda, S.; Nishiyama, Y.; Nakamura-Takahashi, A.; Nitahara-Kasahara, Y.; Imagawa, K.; Hirato, T.; Ueda, M.; et al. Mesenchymal stem cells overexpressing interleukin-10 promote neuroprotection in experimental acute ischemic stroke. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2017, 6, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.Y.; Zhu, G.Y.; Yue, W.J.; Sun, G.D.; Zhu, X.F.; Wang, Y. KLF7 overexpression in bone marrow stromal stem cells graft transplantation promotes sciatic nerve regeneration. J. Neural Eng. 2019, 16, 056011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, C.; Wang, X.; Xu, S. Therapeutic effects of transplantation of As-miR-937-expressing mesenchymal stem cells in murine model of Alzheimer’s disease. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2015, 37, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Disease | Trial Design/Sample Size | MSC Source/Route/Dose | Key Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stroke | Phase I, open-label; 30 patients with acute middle cerebral artery ischemic stroke | Autologous bone marrow-derived MSCs; IV; 1 × 108 cells | Safe; improvement in Barthel Index; trend toward lower modified Rankin Scale; no adverse effects in neuroimaging assessments | [11] |

| Phase I/II; 36 patients with chronic stroke (mean 4.2 years post-event) | Allogeneic bone marrow–derived MSCs; IV; ≤1.5 × 106 cells/kg | Safe; significant improvement in NIHSS, Barthel, MMSE, and depression scale | [12] | |

| Phase III, randomized controlled, open-label; 39 MSC-treated, 15 control patients with chronic ischemic stroke | Autologous MSCs; IV; 1 × 106 cells/kg | Safe; no improvement in 90-day outcomes | [8] | |

| Multiple sclerosis | Phase II, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled; progressive MS | Autologous MSCs-derived–NP; IT; 6 injections of 1 × 107 cells per year | Improved bladder function; reduced gray matter atrophy; altered CSF biomarkers (↑MMP9, ↓CCL2) | [10] |

| Spinal cord injury | Phase I, non-randomized; 6 patients with chronic cervical SCI | Autologous bone marrow–derived MSCs; ITS + IT (two doses); 5 × 107 cells per injection | Safe; no MRI abnormalities; no significant functional improvement | [13] |

| Phase I single-arm, prospective, open-label study; 10 patients with SCI | Autologous adipose-derived MSCs; IT; 1 × 108 cells | Safe; 7/10 patients improved on AIS; high variability among outcomes | [14] | |

| Alzheimer’s disease | Phase I, open-label, single-center; 9 patients with mild-to-moderate AD | Allogeneic umbilical cord blood-derived MSCs; IC; two sequential doses (1.0 × 107 cells/2 mL in the low dose group and 3.0 × 107 cells/2 mL in the high dose group) | Transient fever; reduced tau and Aβ42 post-injection; modest PET improvement; no control group | [15] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Akhmetzyanova, E.; Shulman, I.; Fakhrutdinova, T.; Rizvanov, A.; Mukhamedshina, Y. Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Their Derivatives: Old Problems and New Possibilities in Regenerative Medicine for Neurological Diseases. Biologics 2025, 5, 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/biologics5040037

Akhmetzyanova E, Shulman I, Fakhrutdinova T, Rizvanov A, Mukhamedshina Y. Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Their Derivatives: Old Problems and New Possibilities in Regenerative Medicine for Neurological Diseases. Biologics. 2025; 5(4):37. https://doi.org/10.3390/biologics5040037

Chicago/Turabian StyleAkhmetzyanova, Elvira, Ilya Shulman, Taisiya Fakhrutdinova, Albert Rizvanov, and Yana Mukhamedshina. 2025. "Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Their Derivatives: Old Problems and New Possibilities in Regenerative Medicine for Neurological Diseases" Biologics 5, no. 4: 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/biologics5040037

APA StyleAkhmetzyanova, E., Shulman, I., Fakhrutdinova, T., Rizvanov, A., & Mukhamedshina, Y. (2025). Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Their Derivatives: Old Problems and New Possibilities in Regenerative Medicine for Neurological Diseases. Biologics, 5(4), 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/biologics5040037