Risk of Developing Clostridioides Difficile Infection with the Use of Proton Pump Inhibitors in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

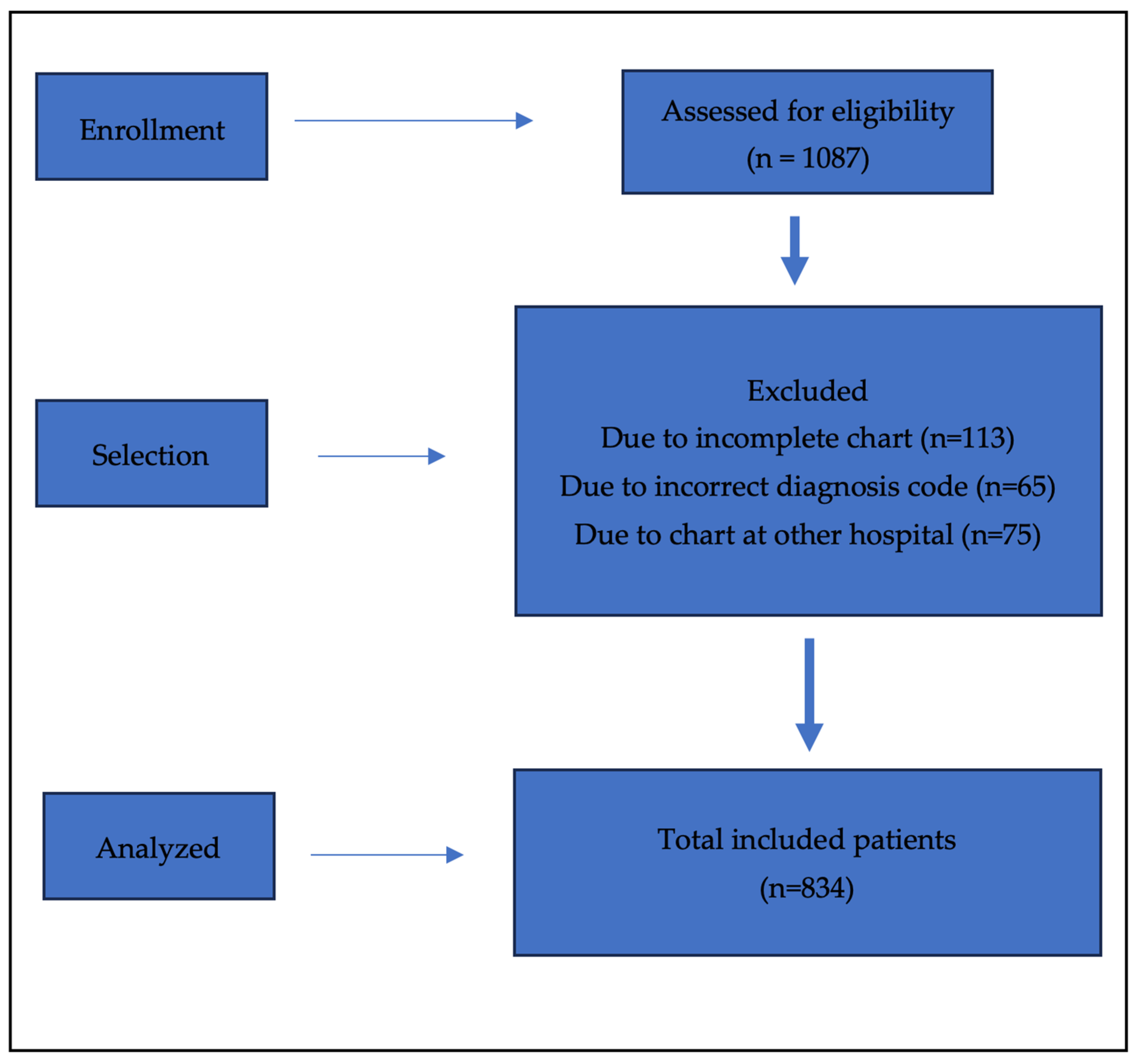

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Sample Size Considerations

2.4. Definition

2.5. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Background Characteristics

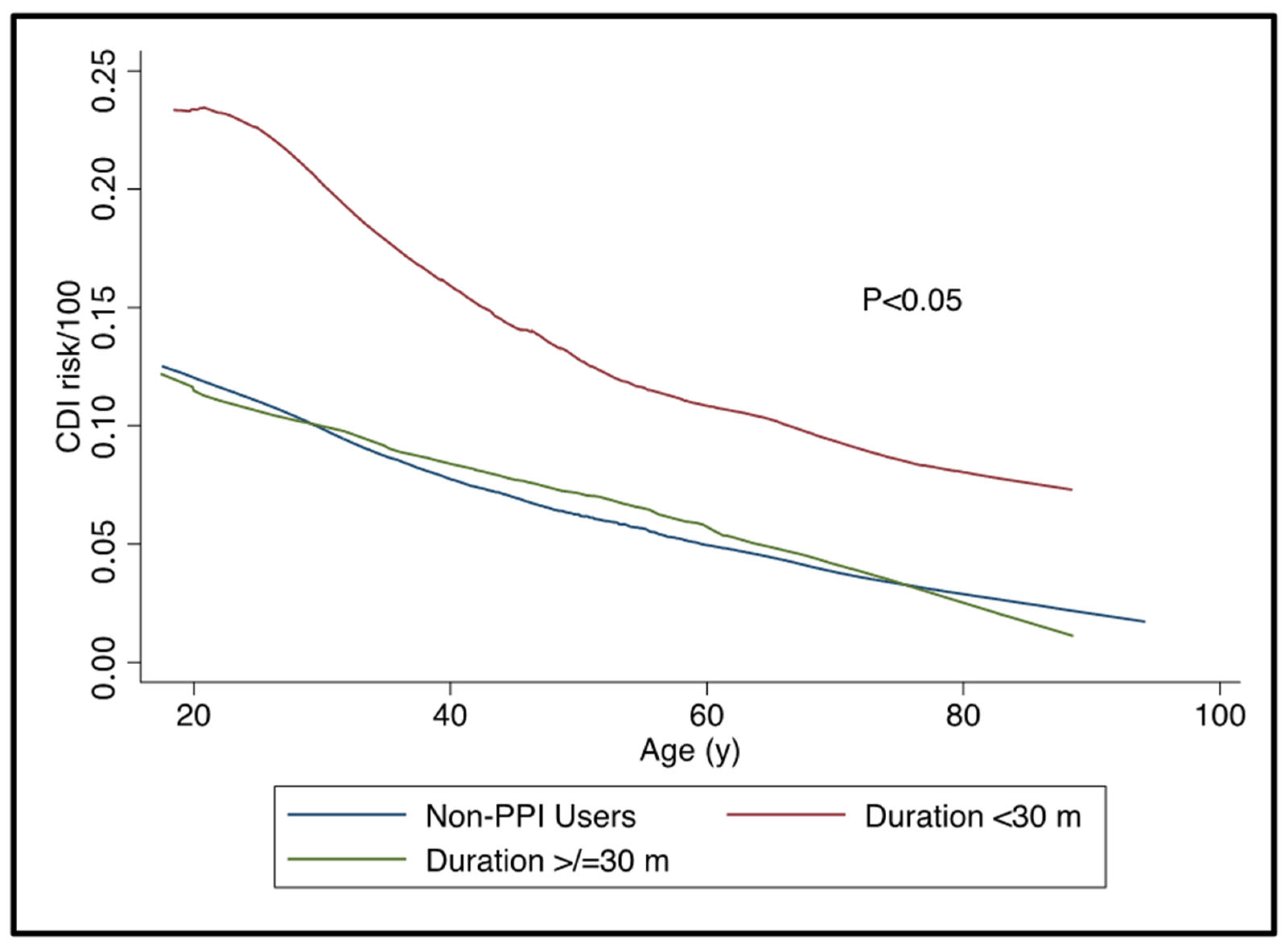

3.2. PPI Use and Risk of CDI

3.3. Corticosteroids, Biologics, and Immunomodulator Use and Risk of CDI

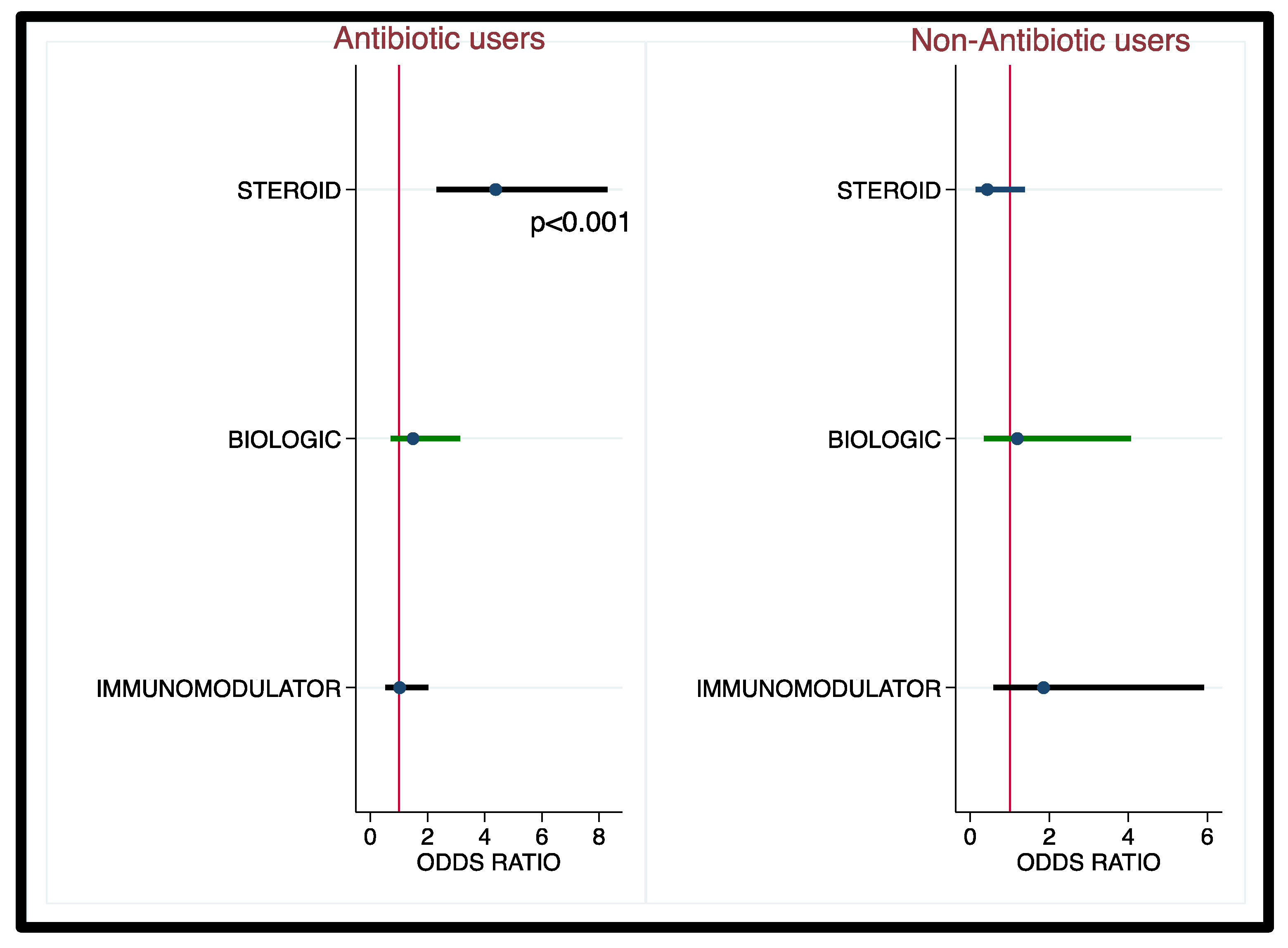

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Balram, B.; Battat, R.; Al-Khoury, A.; D’Aoust, J.; Afif, W.; Bitton, A.; Lakatos, P.L.; Bessissow, T. Risk Factors Associated with Clostridium difficile Infection in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2019, 13, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Issa, M.; Ananthakrishnan, A.N.; Binion, D.G. Clostridium difficile and inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2008, 14, 1432–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshpande, A.; Pant, C.; Pasupuleti, V.; Rolston, D.D.; Jain, A.; Deshpande, N.; Thota, P.; Sferra, T.J.; Hernandez, A.V. Association between proton pump inhibitor therapy and Clostridium difficile infection in a meta-analysis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2012, 10, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janarthanan, S.; Ditah, I.; Adler, D.G.; Ehrinpreis, M.N. Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea and proton pump inhibitor therapy: A meta-analysis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2012, 107, 1001–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pant, C.; Madonia, P.; Minocha, A. Does PPI therapy predispose to Clostridium difficile infection? Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2009, 6, 555–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Martínez, A.; Ortiz-Balbuena, J.; Curto-García, I.; Asensio-Vegas, Á.; Martínez-Ruiz, R.; Múñez-Rubio, E.; Cantero-Caballero, M.; Sánchez-Romero, I.; González-Partida, I.; Vera-Mendoza, M.I. Risk factors for Clostridium difficile diarrhea in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Rev. Esp. Enferm. Dig. 2015, 107, 4–8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Singh, N.; Nugent, Z.; Singh, H.; Shaffer, S.R.; Bernstein, C.N. Proton Pump Inhibitor Use Before and After a Diagnosis of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm. Bowel Diseases 2023, 29, 1871–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kariv, R.; Navaneethan, U.; Venkatesh, P.G.K.; Lopez, R.; Shen, B. Impact of Clostridium difficile infection in patients with ulcerative colitis. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2011, 5, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binion, D. Clostridium difficile Infection and Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016, 12, 334–337. [Google Scholar]

- Trifan, A.; Stanciu, C.; Girleanu, I.; Stoica, O.C.; Singeap, A.M.; Maxim, R.; Chiriac, S.A.; Ciobica, A.; Boiculese, L. Proton pump inhibitors therapy and risk of Clostridium difficile infection: Systematic review and meta-analysis. World J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 23, 6500–6515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yip, C.; Loeb, M.; Salama, S.; Moss, L.; Olde, J. Quinolone use as a risk factor for nosocomial Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea. Infect. Control. Hosp. Epidemiol. 2001, 22, 572–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, J.; Marshall, J.K.; Moayyedi, P. Systematic review of the risk of enteric infection in patients taking acid suppression. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2007, 102, 2047–2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwok, C.S.; Arthur, A.K.; Anibueze, C.I.; Singh, S.; Cavallazzi, R.; Loke, Y.K. Risk of Clostridium difficile infection with acid suppressing drugs and antibiotics: Meta-analysis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2012, 107, 1011–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaulieu, M.; Williamson, D.; Pichette, G.; Lachaine, J. Risk of Clostridium difficile-associated disease among patients receiving proton-pump inhibitors in a Quebec medical intensive care unit. Infect. Control. Hosp. Epidemiol. 2007, 28, 1305–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McFarland, L.V. Update on the changing epidemiology of Clostridium difficile-associated disease. Nat. Clin. Pract. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2008, 5, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, S.; Lewis, A.; Leopold, D.; Dunstan, F.; Woodhouse, K. Gastric acid suppression does not promote clostridial diarrhoea in the elderly. QJM Int. J. Med. 2000, 93, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micic, D.; Yarur, A.; Gonsalves, A.; Rao, V.L.; Broadaway, S.; Cohen, R.; Dalal, S.; Gaetano, J.N.; Glick, L.R.; Hirsch, A.; et al. Risk Factors for Clostridium difficile Isolation in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Prospective Study. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2018, 63, 1016–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regnault, H.; Bourrier, A.; Lalande, V.; Nion-Larmurier, I.; Sokol, H.; Seksik, P.; Barbut, F.; Cosnes, J.; Beaugerie, L. Prevalence and risk factors of Clostridium difficile infection in patients hospitalized for flare of inflammatory bowel disease: A retrospective assessment. Dig. Liver Dis. 2014, 46, 1086–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Lin, Q.Y.; Fei, J.X.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, M.Y.; Jiang, S.H.; Wang, P.; Chen, Y. Clostridium Difficile Infection Worsen Outcome of Hospitalized Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 29791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoica, O.; Trifan, A.; Cojocariu, C.; Gîrleanu, I.; Maxim, R.; Stanciu, M.C. Incidence and risk factors of Clostridium difficile infection in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Med. Surg. J. 2015, 119, 81–86. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, Y.B.; Zhang, M.C.; Sun, J.; Lv, K.Z.; Zhong, J. Risk factors and clinical outcome of Clostridium difficile infection in patients with IBD: A single-center retrospective study of 260 cases in China. J. Dig. Dis. 2017, 18, 207–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehault, W.B.; Hughes, D.M. Review of the Long-Term Effects of Proton Pump Inhibitors. Fed. Pract. 2017, 34, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tawam, D.; Baladi, M.; Jungsuwadee, P.; Earl, G.; Han, J. The Positive Association between Proton Pump Inhibitors and Clostridium Difficile Infection. Innov. Pharm. 2021, 12, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalal, R.S.; Allegretti, J.R. Diagnosis and management of Clostridioides difficile infection in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 2021, 37, 336–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodemann, J.F.; Dubberke, E.R.; Reske, K.A.; Seo, D.H.; Stone, C.D. Incidence of Clostridium difficile infection in inflammatory bowel disease. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2007, 5, 339–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navaneethan, U.; Venkatesh, P.G.; Shen, B. Clostridium difficile infection and inflammatory bowel disease: Understanding the evolving relationship. World J. Gastroenterol. 2010, 16, 4892–4904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.S.; Li, B.Y.; Chen, Q.T.; Song, C.Y.; Shi, J.; Shi, B. Comparison of the Use of Vonoprazan and Proton Pump Inhibitors for the Treatment of Peptic Ulcers Resulting from Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Med. Sci. Monit. Int. Med. J. Exp. Clin. Res. 2019, 25, 1169–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Mean/Prevalence |

|---|---|

| Mean Age (y) (Range) | 47 (17–94) |

| Female Gender (%) | 500 (60) |

| IBD type | |

| 485 (58) |

| 349 (42) |

| Race | |

| 771 (92) |

| 63 (8) |

| 72 (9) |

| Therapeutic use rate | |

| 350 (42) |

| 348 (42) |

| 278 (33) |

| 449 (53) |

| 344 (41) |

| 105 (13) |

| Average PPI use duration, months | 30 (0.1–255) |

| Medication | OR (95% CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Proton pump Inhibitor | ||

| Non-users | 1.00 | --- |

| Users | 1.54 (0.98–2.53) | 0.08 |

| Histamine-2 Receptor Antagonist | ||

| Non-users | 1.00 | --- |

| Users | 0.91 (0.4–1.89) | 0.037 |

| Antibiotics | ||

| Non-users | 1.00 | |

| Users | 6.33 (3.51, 11.39) | <0.001 |

| Corticosteroids | ||

| Non-users | 1.00 | |

| Users | 1.54 (0.95, 2.40) | 0.08 |

| Biologics | ||

| Non-users | 1.00 | |

| Users | 2.22 (1.31, 3.76) | 0.003 |

| Immunomodulators | ||

| Non-users | 1.00 | |

| Users | 2.02 (1.24, 3.29) | 0.004 |

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio (CI) | p-Value | Relative Risk (CI) | p-Value | |

| PPI | ||||

| Non-users (n = 523) | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - |

| Users (n = 358) | 1.58 (0.98–2.53) | 0.06 | 9.23 (2.11–40.34) | 0.003 |

| Antibiotic Users (n = 347) | Non-Antibiotic Users (n = 517) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (CI) | p-Value | OR (CI) | p-Value | |

| Corticosteroids | ||||

| Non-users (n = 513) | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | |

| Users (n = 351) | 3.71 (1.90–7.23) | <0.001 | 0.12 (0.01–1.05) | 0.055 |

| Immunomodulators | ||||

| Non-users (n = 586) | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | |

| Users (n = 278) | 0.77 (0.40–1.49) | 0.439 | 2.54 (0.48–13.6) | 0.276 |

| Biologics | ||||

| Non-users (n = 414) | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | |

| Users (n = 450) | 2.47 (1.08–5.68) | 0.033 | 0.74 (0.14–3.94) | 0.727 |

| Variable | Category | With CDI (N/%) | Without CDI (N/%) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 42.50 ± 17.67 | 48.23 ± 17.10 | 0.0058 | |

| Race | Caucasian | 72 (9.10%) | 719 (90.90%) | 0.219 |

| Minority | 3 (4.62%) | 62 (95.38%) | ||

| Gender | Male | 27 (7.99%) | 311 (92.01%) | 0.518 |

| Female | 48 (9.27%) | 470 (90.73%) | ||

| Antibiotics | Yes | 57 (16.57%) | 287 (83.43%) | <0.001 |

| No | 15 (3.06%) | 475 (96.94%) | ||

| Steroid Use | Yes | 41 (11.55%) | 314 (88.45%) | 0.015 |

| No | 34 (6.79%) | 467 (93.21%) | ||

| PPI Use | Yes | 39 (11.02%) | 315 (88.98%) | 0.058 |

| No | 36 (7.27%) | 459 (92.73%) | ||

| IBD Category | CD | 37 (7.74%) | 441 (92.26%) | 0.241 |

| UC | 36 (10.06%) | 322 (89.94%) | ||

| Immunomodulators | Yes | 45 (7.08%) | 591 (92.92%) | 0.004 |

| No | 28 (14.81%) | 161 (85.19%) | ||

| Biologics | Yes | 53 (11.57%) | 405 (88.43%) | 0.002 |

| No | 22 (5.53%) | 376 (94.47%) | ||

| H2 receptor antagonist | Yes | 9 (8.04%) | 103 (91.96%) | 0.801 |

| No | 64 (8.76%) | 667 (91.24%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gandhi, M.; Chela, H.K.; Barffour, M.A.; Bosak, E.; Reznicek, E.; Luton, K.; Bechtold, M.; Ghouri, Y.A. Risk of Developing Clostridioides Difficile Infection with the Use of Proton Pump Inhibitors in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Biologics 2025, 5, 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/biologics5040038

Gandhi M, Chela HK, Barffour MA, Bosak E, Reznicek E, Luton K, Bechtold M, Ghouri YA. Risk of Developing Clostridioides Difficile Infection with the Use of Proton Pump Inhibitors in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Biologics. 2025; 5(4):38. https://doi.org/10.3390/biologics5040038

Chicago/Turabian StyleGandhi, Mustafa, Harleen Kaur Chela, Maxwell A. Barffour, Emily Bosak, Emily Reznicek, Kevin Luton, Matthew Bechtold, and Yezaz A. Ghouri. 2025. "Risk of Developing Clostridioides Difficile Infection with the Use of Proton Pump Inhibitors in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease" Biologics 5, no. 4: 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/biologics5040038

APA StyleGandhi, M., Chela, H. K., Barffour, M. A., Bosak, E., Reznicek, E., Luton, K., Bechtold, M., & Ghouri, Y. A. (2025). Risk of Developing Clostridioides Difficile Infection with the Use of Proton Pump Inhibitors in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Biologics, 5(4), 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/biologics5040038