Towards a Social Model of Prematurity: Understanding the Social Impact of Prematurity and the Role of Inclusive Parenting Practices in Neonatal Intensive Care Units

Definition

1. Introduction

2. Social Impact of Prematurity

3. Parental Inclusion in the NICU

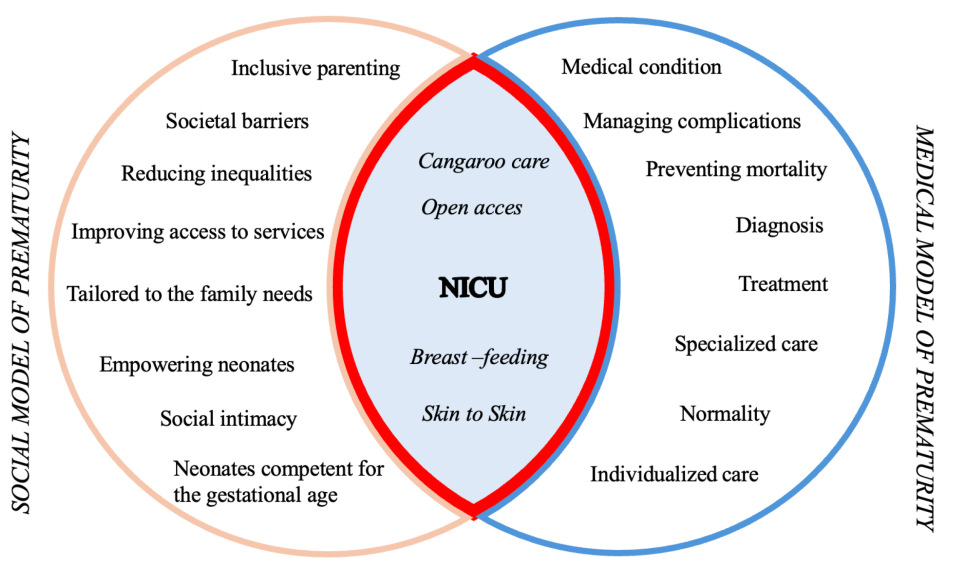

4. Social and Medical Model of Disability

5. Social and Medical Models of Prematurity

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Recommendations on Interventions to Improve Preterm Birth Outcomes; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK321160/ (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Petrou, S.; Yiu, H.H.; Kwon, J. Economic Consequences of Preterm Birth: A Systematic Review of the Recent Literature (2009–2017). Arch. Dis. Child. 2019, 104, 456–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konukbay, D.; Vural, M.; Yildiz, D. Parental Stress and Nurse-Parent Support in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Nurs. 2024, 23, 820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khurana, S.; Kane, A.E.; Brown, S.E.; Tarver, T.; Dusing, S.C. Effect of Neonatal Therapy on the Motor, Cognitive, and Behavioral Development of Infants Born Preterm: A Systematic Review. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2020, 62, 684–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, P.; Pais, M.; Kamath, S.; Pai, M.V.; Lewis, L.; Bhat, R. Perceived Maternal Parenting Self-Efficacy and Parent Coping among Mothers of Preterm Infants—A Cross-Sectional Survey. Manipal J. Med. Sci. 2018, 18, 40. [Google Scholar]

- Als, H.; Butler, S.; Kosta, S.; McAnulty, G. The Assessment of Preterm Infants’ Behavior (APIB): Furthering the Understanding and Measurement of Neurodevelopmental Competence in Preterm and Full-Term Infants. Ment. Retard. Dev. Disabil. Res. Rev. 2005, 11, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawhon, G.; Hedlund, R.E. Newborn Individualized Developmental Care and Assessment Program Training and Education. J. Perinat. Neonatal Nurs. 2008, 22, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineda, R.G.; Neil, J.; Dierker, D.; Smyser, C.D.; Wallendorf, M.; Kidokoro, H.; Reynolds, L.C.; Walker, S.; Rogers, C.; Mathur, A.M.; et al. Alterations in Brain Structure and Neurodevelopmental Outcome in Preterm Infants Hospitalized in Different Neonatal Intensive Care Unit Environments. J. Pediatr. 2014, 164, 52–60.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Als, H. Toward a Synactive Theory of Development: Promise for the Assessment and Support of Infant Individuality. Infant Ment. Health J. 1982, 3, 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brazelton, T.B. The Remarkable Talents of the Newborn. Birth Fam. J. 1978, 5, 187–191. [Google Scholar]

- Smyser, C.D.; Inder, T.E.; Shimony, J.S.; Hill, J.E.; Degnan, A.J.; Snyder, A.Z.; Neil, J.J. Longitudinal Analysis of Neural Network Development in Preterm Infants. Cereb. Cortex 2010, 20, 2852–2862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Als, H. The Newborn Communicates. J. Commun. 1977, 27, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brazelton, T.B.; Nugent, J.K. The Neonatal Behavioral Assessment Scale, 4th ed.; Mac Keith Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Prechtl, H.F.R. Motor Behaviour in Relation to Brain Structure. In Normal and Abnormal Development of Brain and Behaviour; Stoelinga, G.B.A., Van Der Werff Ten Bosch, J.J., Eds.; Boerhaave Series for Postgraduate Medical Education; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1971; Volume 6, pp. 133–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, C.; Raver, C.C. Individual Development and Evolution: Experiential Canalization of Self-Regulation. Dev. Psychol. 2012, 48, 647–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, N.F.; Linhares, M.B.M.; Gaspardo, C.M. Stress and Self-Regulation Behaviors in Preterm Neonates Hospitalized at Open-Bay and Single-Family Room Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. Infant Behav. Dev. 2024, 76, 101951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchard, Y.; Mouradian, L. Integrating Neurobehavioral Concepts into Early Intervention Eligibility Evaluation. Infants Young Child. 2000, 13, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefana, A.; Lavelli, M. Parental Engagement and Early Interactions with Preterm Infants during the Stay in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit: Protocol of a Mixed-Method and Longitudinal Study. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e013824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brazelton, T.B. Early Intervention: What Does It Mean. In Theory and Research in Behavioral Pediatrics; Fitzgerald, H.E., Lester, B.M., Yogman, M.W., Eds.; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1982; Volume 1, pp. 3–33. [Google Scholar]

- Mendonça, M.; Bilgin, A.; Wolke, D. Association of Preterm Birth and Low Birth Weight with Romantic Partnership, Sexual Intercourse, and Parenthood in Adulthood: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e196961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bracht, M.; Franck, L.S.; O’Brien, K.; Bacchini, F. Parents Are Not Visiting. Parents Are Parenting. Adv. Neonatal Care 2023, 23, 105–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baughcum, A.E.; Clark, O.E.; Lassen, S.; Fortney, C.A.; Rausch, J.A.; Dunnells, Z.D.O.; Geller, P.A.; Olsavsky, A.; Patterson, C.A.; Gerhardt, C.A. Preliminary Validation of the Psychosocial Assessment Tool in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2023, 48, 503–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaaresen, P.I.; Rønning, J.A.; Ulvund, S.E.; Dahl, L.B. A Randomized, Controlled Trial of the Effectiveness of an Early-Intervention Program in Reducing Parenting Stress after Preterm Birth. Pediatrics 2006, 118, e9–e19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stegmann-Woessner, G.; Bartmann, P.; Mitschdoerfer, B.; Wolke, D. Forever premature: Adults born preterm and their life challenges. Early Hum. Dev. 2025, 204, 106248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Costa, A.; Moller, A.B.; Blencowe, H.; Johansson, E.W.; Hussain-Alkhateeb, L.; Ohuma, E.O.; Okwaraji, Y.B.; Cresswell, J.; Requejo, J.H.; Bahl, R.; et al. Study Protocol for WHO and UNICEF Estimates of Global, Regional, and National Preterm Birth Rates for 2010 to 2019. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0258751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodek, J.M.; Von der Schulenburg, J.M.; Mittendorf, T. Measuring Economic Consequences of Preterm Birth—Methodological Recommendations for the Evaluation of Personal Burden on Children and Their Caregivers. Health Econ. Rev. 2011, 1, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Shen, H.; Jin, Q.; Zhou, L.; Feng, L. Family-Centered Care in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review of Outcomes for Preterm Infants. Transl. Pediatr. 2025, 14, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mariani, I.; Vuillard, C.L.J.; Bua, J.; Girardelli, M.; Lazzerini, M. Family-Centred Care Interventions in Neonatal Intensive Care Units: A Scoping Review of Randomised Controlled Trials Providing a Menu of Interventions, Outcomes and Measurement Methods. BMJ Paediatr. Open 2024, 8 (Suppl. 2), e002537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gath, M.E.; Lee, S.J.; Austin, N.C.; Woodward, L.J. Increased Risk of Parental Instability for Children Born Very Preterm and Impacts on Neurodevelopmental Outcomes at Age 12. Children 2022, 9, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legge, N.; Popat, H.; Fitzgerald, D. Examining the Impact of Premature Birth on Parental Mental Health and Family Functioning in the Years Following Hospital Discharge: A Review. J. Neonatal-Perinat. Med. 2023, 16, 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, R.; Walsh, D.; Scott, S.; Carruthers, J.; Fenton, L.; McCartney, G.; Moore, E. Is the Period of Austerity in the UK Associated with Increased Rates of Adverse Birth Outcomes? Eur. J. Public Health 2024, 34, 1043–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Yang, B.; Meng, L.; Wang, B.; Zheng, C.; Cao, A. Effect of Early Intervention on Premature Infants’ General Movements. Brain Dev. 2015, 37, 387–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, J.; Walls, M.; McGuire, W. Respiratory Complications of Preterm Birth. BMJ 2004, 329, 962–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Z.; Vowles, Z.; Fernandez Turienzo, C.; Barry, Z.; Brigante, L.; Downe, S.; Easter, A.; Harding, S.; McFadden, A.; Montgomery, E.; et al. Targeted health and social care interventions for women and infants who are disproportionately impacted by health inequalities in high-income countries: A systematic review. Int. J. Equity Health 2023, 22, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundqvist, P.; Weis, J.; Sivberg, B. Parents’ Journey Caring for a Preterm Infant until Discharge from Hospital-Based Neonatal Home Care—A Challenging Process to Cope With. J. Clin. Nurs. 2019, 28, 2966–2978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayode, G.; Howell, A.; Burden, C.; Margelyte, R.; Cheng, V.; Viner, M.; Sandall, J.; Carter, J.; Brigante, L.; Winter, C.; et al. Socioeconomic and Ethnic Disparities in Preterm Births in an English Maternity Setting: A Population-Based Study of 1.3 Million Births. BMC Med. 2024, 22, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blencowe, H.; Cousens, S.; Chou, D.; Oestergaard, M.; Say, L.; Moller, A.-B.; Kinney, M.; Lawn, J. Born too soon: The global epidemiology of 15 million preterm births. Reprod. Health 2013, 10 (Suppl. 1), S2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Preterm Birth. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/preterm-birth (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Stern, D.N. New Introduction to the Paperback Edition of The Interpersonal World of the Infant; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2000; pp. xi–xl. [Google Scholar]

- Luu, T.M.; Rehman Mian, M.O.; Nuyt, A.M. Long-Term Impact of Preterm Birth: Neurodevelopmental and Physical Health Outcomes. Clin. Perinatol. 2017, 44, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hans, S.L.; Bernstein, V.J.; Percansky, C. Adolescent Parenting Programs: Assessing Parent-Infant Interaction. Eval. Program Plann. 1991, 14, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oltra-Benavent, P.; Cano-Climent, A.; Oliver-Roig, A.; Cabrero-García, J.; Richart-Martínez, M. Spanish Version of the Parenting Sense of Competence Scale: Evidence of Reliability and Validity. Child Fam. Soc. Work 2020, 25, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippa, M.; Panza, C.; Ferrari, F.; Frassoldati, R.; Kuhn, P.; Balduzzi, S.; D’Amico, R. Systematic Review of Maternal Voice Interventions Demonstrates Increased Stability in Preterm Infants. Acta Paediatr. 2017, 106, 1220–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brisch, K.H.; Bechinger, D.; Betzler, S.; Heinemann, H. Early Preventive Attachment-Oriented Psychotherapeutic Intervention Program with Parents of a Very Low Birthweight Premature Infant: Results of Attachment and Neurological Development. Attach. Hum. Dev. 2003, 5, 120–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holditch-Davis, D.; Miles, M.S. Mothers’ Stories about Their Experiences in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. Neonatal Netw. 2000, 19, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, V.J.; Hans, S.L.; Percansky, C. Advocating for the Young Child in Need through Strengthening the Parent-Child Relationship. J. Clin. Child Psychol. 1991, 20, 28–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, R.; Weller, A.; Sirota, L.; Eidelman, A.I. Skin-to-Skin Contact (Kangaroo Care) Promotes Self-Regulation in Premature Infants: Sleep-Wake Cyclicity, Arousal Modulation, and Sustained Exploration. Dev. Psychol. 2002, 38, 194–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aija, A.; Toome, L.; Axelin, A.; Raiskila, S.; Lehtonen, L. Parents’ Presence and Participation in Medical Rounds in 11 European Neonatal Units. Early Hum. Dev. 2019, 130, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, S.; Bredemeyer, S.; Chiarella, M. The evolution of neonatal family-centred care. J. Neonatal Nurs. 2021, 27, 327–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.H.M.; Campbell-Yeo, M.; Disher, T.; Dol, J.; Richardson, B.; Chez NICU Home Team; Bishop, T.; Delahunty-Pike, A.; Dorling, J.; Glover, M.; et al. Caregiver presence and involvement in a Canadian neonatal intensive care unit: An observational cohort study. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2021, 60, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz, N.; Piskernik, B.; Witting, A.; Fuiko, R.; Ahnert, L. Parent-child attachment in children born preterm and at term: A multigroup analysis. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0202972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemle Jerntorp, S.; Sivberg, B.; Lundqvist, P. Fathers’ lived experiences of caring for their preterm infant at the neonatal unit and in neonatal home care after the introduction of a parental support programme: A phenomenological study. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2021, 35, 1143–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, C. How Is Disability Understood? An Examination of Sociological Approaches. Disabil. Soc. 2004, 19, 569–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deegan, M.J. “Feeling Normal” and “Feeling Disabled”. In Research in Social Science and Disability, Volume 5: Disability as a Fluid State; Barnartt, S.N., Altman, B.M., Eds.; Emerald Group: Plymouth, UK, 2010; p. 34. [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin, J. Screening Networks: Shared Agendas in Feminist and Disability Movement Challenges to Antenatal Screening and Abortion. Disabil. Soc. 2003, 18, 297–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Union of the Physically Impaired Against Segregation (UPIAS). Comments on the Discussion Held between the Union and the Disability Alliance on 22nd November 1975; UPIAS 1975:4. Available online: https://www.yumpu.com/en/document/view/26838497/upias-fundamental-principles (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Shakespeare, T. Social models of disability and other life strategies. Scand. J. Disabil. Res. 2004, 6, 8–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, M. The Politics of Disablement; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 1990; pp. 45–46. [Google Scholar]

- Skär, L.; Tamm, M. Disability and Social Network: A Comparison between Children and Adolescents with and without Restricted Mobility. Scand. J. Disabil. Res. 2002, 4, 118–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kuper, H.; Hameed, S.; Reichenberger, V.; Scherer, N.; Wilbur, J.; Zuurmond, M.; Mactaggart, I.; Bright, T.; Shakespeare, T. Participatory research in disability in low- and middle-income countries: What have we learnt and what should we do? Scand. J. Disabil. Res. 2021, 23, 328–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grech, S. Recolonising debates or perpetuated coloniality? Decentring the spaces of disability, development and community in the global South. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2011, 15, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakespeare, T. Disability Rights and Wrongs Revisited, 2nd ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2014; pp. 46,101. [Google Scholar]

- Berghs, M. Biosocial Model of Disability. In Encyclopedia of Gerontology and Population Aging; Gu, D., Dupre, M.E., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, H.K.; Speechley, K.N.; Macnab, J.; Natale, R.; Campbell, M.K. Mild prematurity, proximal social processes, and development. Pediatrics 2014, 134, e814–e824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kramer, M.R.; Hogue, C.R. What Causes Racial Disparities in Very Preterm Birth? A Biosocial Perspective. Epidemiol. Rev. 2009, 31, 84–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burris, H.; Baccarelli, A.; Wright, R.; Wright, R.J. Epigenetics: Linking Social and Environmental Exposures to Preterm Birth. Pediatr. Res. 2016, 79, 136–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.D.; Green, C.A.; Vladutiu, C.J.; Manuck, T.A. Racial Disparities in Prematurity Persist among Women of High Socioeconomic Status. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. MFM 2020, 2, 100104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braveman, P.; Heck, K.; Dominguez, T.P.; Marchi, K.; Burke, W.; Holm, N. African immigrants’ favorable preterm birth rates challenge genetic etiology of the Black–White disparity in preterm birth. Front. Public Health 2024, 11, 1321331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokkinaki, T.; Anagnostatou, N.; Markodimitraki, M.; Roumeliotaki, T.; Tzatzarakis, M.; Vakonaki, E.; Giannakakis, G.; Tsatsakis, A.; Hatzidaki, E. The Development of Preterm Infants from Low Socio-Economic Status Families: The Combined Effects of Melatonin, Autonomic Nervous System Maturation and Psychosocial Factors (ProMote): A Study Protocol. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0316520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keenan-Devlin, L.S.; Smart, B.P.; Grobman, W.; Adam, E.K.; Freedman, A.; Buss, C.; Entringer, S.; Miller, G.E.; Borders, A.E.B. The Intersection of Race and Socioeconomic Status Is Associated with Inflammation Patterns during Pregnancy and Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2022, 87, e13489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugent, J.K. Historical perspectives: Berry Brazelton: Le magnifique. NeoReviews 2019, 20, e615–e621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Agata, A.L.; Green, C.E.; Sullivan, M.C. A new patient population for adult clinicians: Preterm born adults. Lancet Reg. Health Am. 2022, 9, 100188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Moscholouri, C.; Kortianou, E.A.; Kanellopoulos, A.K.; Papastathopoulos, E.; Daskalaki, A.; Hatzidaki, E.; Trigkas, P. Towards a Social Model of Prematurity: Understanding the Social Impact of Prematurity and the Role of Inclusive Parenting Practices in Neonatal Intensive Care Units. Encyclopedia 2025, 5, 150. https://doi.org/10.3390/encyclopedia5030150

Moscholouri C, Kortianou EA, Kanellopoulos AK, Papastathopoulos E, Daskalaki A, Hatzidaki E, Trigkas P. Towards a Social Model of Prematurity: Understanding the Social Impact of Prematurity and the Role of Inclusive Parenting Practices in Neonatal Intensive Care Units. Encyclopedia. 2025; 5(3):150. https://doi.org/10.3390/encyclopedia5030150

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoscholouri, Chrysoula, Eleni A. Kortianou, Asimakis K. Kanellopoulos, Efstathios Papastathopoulos, Anna Daskalaki, Eleftheria Hatzidaki, and Panagiotis Trigkas. 2025. "Towards a Social Model of Prematurity: Understanding the Social Impact of Prematurity and the Role of Inclusive Parenting Practices in Neonatal Intensive Care Units" Encyclopedia 5, no. 3: 150. https://doi.org/10.3390/encyclopedia5030150

APA StyleMoscholouri, C., Kortianou, E. A., Kanellopoulos, A. K., Papastathopoulos, E., Daskalaki, A., Hatzidaki, E., & Trigkas, P. (2025). Towards a Social Model of Prematurity: Understanding the Social Impact of Prematurity and the Role of Inclusive Parenting Practices in Neonatal Intensive Care Units. Encyclopedia, 5(3), 150. https://doi.org/10.3390/encyclopedia5030150