Post-2024 UK International Student Supply Chain Challenges

Definition

1. Introduction

1.1. History of International Students

1.2. The UK Context

1.3. Research Context

2. Data

2.1. Insights on Recent Int-Student Supply Chain Trends

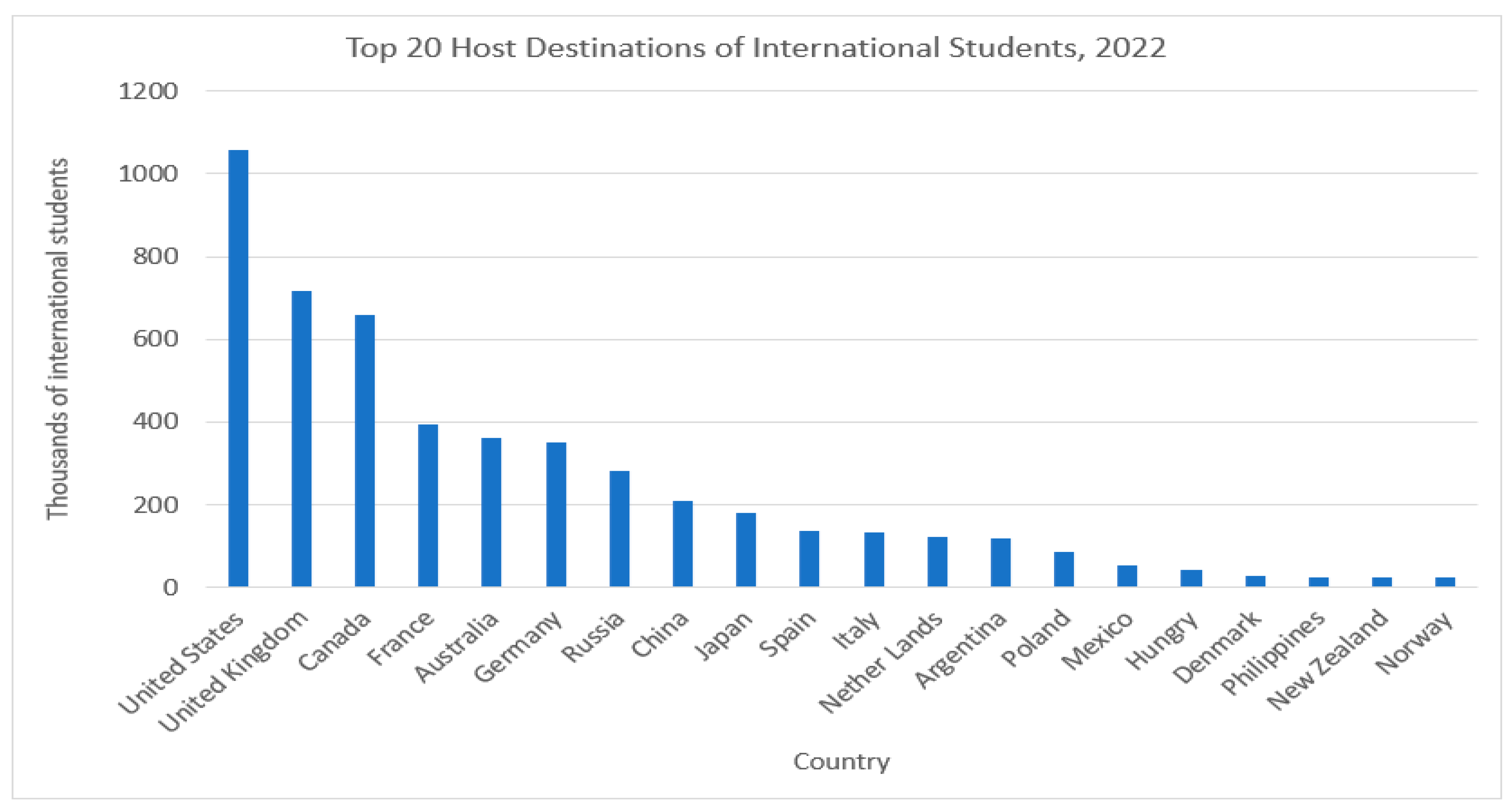

2.2. Top Receiving Countries of Int-Students

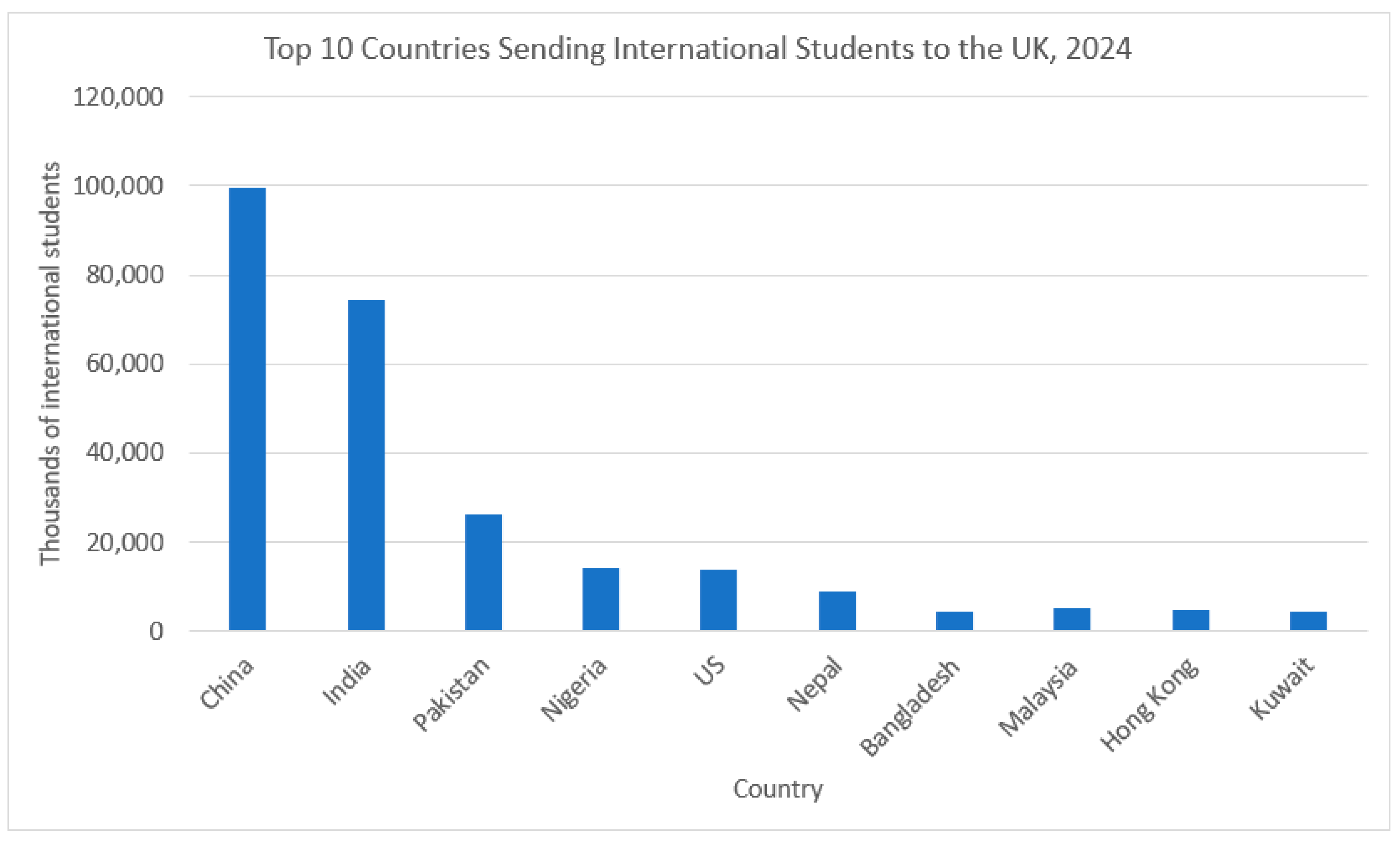

2.3. Top Sending Countries to the UK

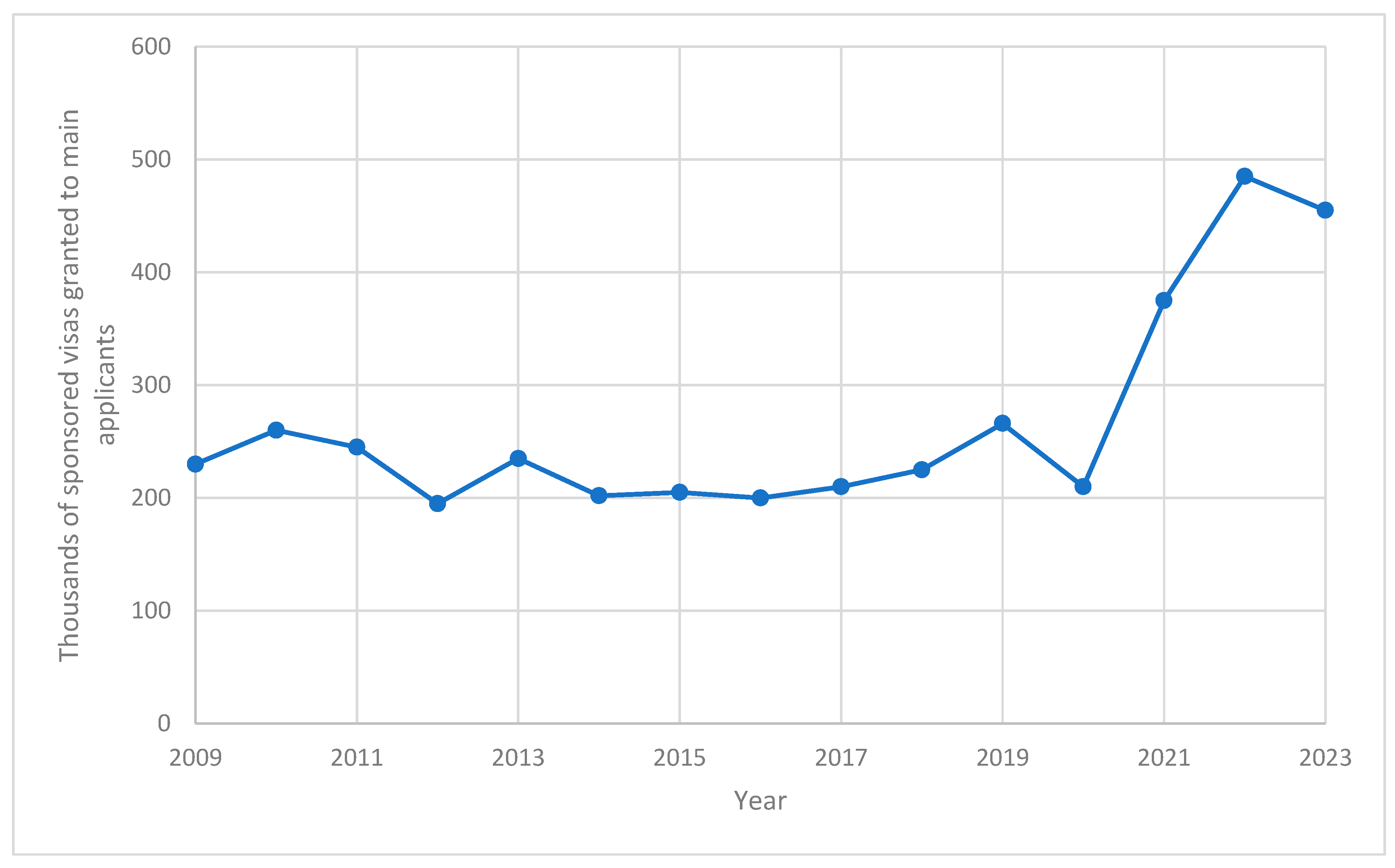

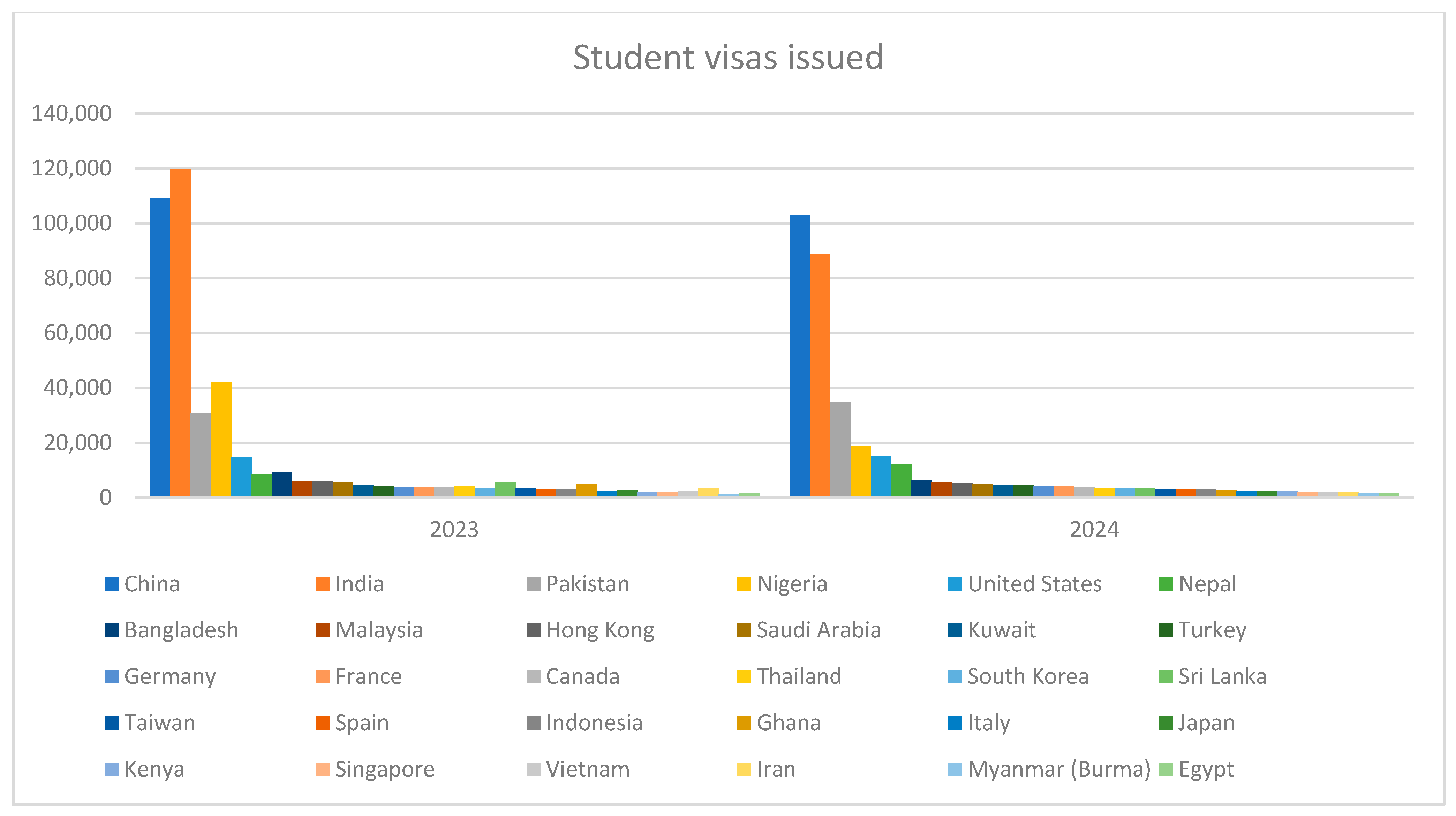

2.4. Trends in Int-Student Numbers in the UK

3. Potential Challenges for the UK Int-Student Market

3.1. Competition from Other Major Destinations

3.2. Competition from Emerging International Study Destinations

3.3. Political Direction and Immigration Policy in the UK

3.4. Rising Costs

3.5. Growth of Online and Distance Education

3.6. Offshore Campuses

3.7. Geopolitical Conflicts

3.8. Diversity Issues

3.9. Economic Crisis and Financial Constraints

4. Conclusions and Prospects

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HEI | Higher Educational Institute |

| Int-student | International Student |

References

- Gutek, G.L. A History of the Western Educational Experience, 2nd ed.; Waveland Press: Long Grove, IL, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, M.A. Manifesto for the postcolonial university. Educ. Philos. Theory 2019, 51, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoque, M.N.; Abdullah, M.F. The world’s oldest university and its financing experience: A study on Al-Qarawiyyin University (859–990). J. Nusant. Stud. 2021, 6, 24–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashdall, H. The origins of the University of Paris. Engl. Hist. Rev. 1886, 1, 639–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Leader, D.R.; Searby, P. A History of the University of Cambridge: Volume 1, The University to 1546; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Cronin, B. Cathedrals of Learning: Great and Ancient Universities of Western Europe; Chandos Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Altbach, P.G.; Reisberg, L.; Rumbley, L.E. Trends in Global Higher Education: Tracking an Academic Revolution; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2019; Volume 22. [Google Scholar]

- Bevis, T.B. A World History of Higher Education Exchange; Springer International Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Guruz, K. Higher Education and International Student Mobility in the Global Knowledge Economy, 2nd ed.; SUNY Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Focacci, C.N.; Perez, C. The importance of education and training policies in supporting technological revolutions. Technol. Soc. 2022, 70, 102000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swartz, R. Education and Empire: Children, Race and Humanitarianism in the British Settler Colonies; Palgrave MacMillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Schofer, E.; Meyer, J.W. The worldwide expansion of higher education in the twentieth century. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2005, 70, 898–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartnicka, K. Access of Higher Education and Study for Poles in the Second Half of 19th Century. The Reception of Exact Sciences in Central-Eastern Europe in 1850–1920. Available online: http://repozytorium.biblos.pk.edu.pl/resources/35440 (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- De Wit, H.; Merkx, G. The History of the Internationalization of Higher Education. In The Handbook of International Higher Education, 2nd ed.; Charles, H., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2022; pp. 23–52. [Google Scholar]

- Marginson, S.; Van der Wende, M. The New Global Landscape of Nations and Institutions. In Higher Education to 2030, Volume 2: Globalisation; OECD Publications: Paris, France, 2009; pp. 17–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marginson, S. Dynamics of national and global competition in higher education. High. Educ. 2006, 52, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, C. The Contribution of Education to Economic Growth; Institute of Development Studies: Brighton, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, J. The Future for International Students in the UK. Available online: https://www.hepi.ac.uk/2023/06/14/future-for-international-students-in-the-uk-by-jo-johnson/ (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Cardiff University. Securing Our Academic Future. Available online: https://www.cardiff.ac.uk/news/view/2894086-securing-our-academic-future (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Rother, E.T. Systematic literature review X narrative review. Acta Paul. Enferm. 2007, 20, v–vi. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO Institute for Statistics. UIS Data Browser. Available online: https://databrowser.uis.unesco.org/browser/EDUCATION/UIS-EducationOPRI/int-stud/outbound (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- Statista. Top Host Destination of International Students Worldwide in 2022, by Number of Students. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/297132/top-host-destination-of-international-students-worldwide/ (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- Tight, M. How many universities are there in the United Kingdom? How many should there be? High. Educ. 2011, 62, 649–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moody, J. How Many Universities are in the US and Why That Number is Changing. U.S. News. 27 April 2021. Available online: https://www.usnews.com/education/best-colleges/articles/how-many-universities-are-in-the-us-and-why-that-number-is-changing (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- Bartram, B.; Terano, M. Supporting international students in higher education: A comparative examination of approaches in the UK and USA. Learn. Teach. 2011, 4, 30–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Wit, H.; Minaeva, E.; Wang, L. International Student Recruitment and Mobility in Non-Anglophone Countries; Routledge: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Verbik, L.; Lasanowski, V. International student mobility: Patterns and trends. World Educ. News Rev. 2007, 20, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Beech, S.E. The Geographies of International Student Mobility: Spaces, Places and Decision-Making; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bolton, P.; Lewis, J.; Gower, M. International Students in UK Higher Education; House of Commons Library: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- British Council. UK Q3 Visa Data Shows Significant Drop in Incoming Students. Available online: https://opportunities-insight.britishcouncil.org/short-articles/news/uk-q3-visa-data-shows-significant-drop-incoming-students (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- Alqahtani, A. Evaluation of King Abdullah Scholarship Program. J. Educ. Pract. 2014, 5, 33–42. [Google Scholar]

- Redden, E. Saudi Student Numbers Fall at Many Campuses. Inside Higher Ed. 18 July 2016. Available online: https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2016/07/18/saudi-student-numbers-fall-many-campuses (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- Nery, M.B.M. Science without borders’ contributions to internationalization of Brazilian higher education. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 2018, 22, 371–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sá, C.M. The rise and fall of Brazil’s Science Without Borders. Int. High. Educ. 2016, 85, 17–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICEF Monitor. Brazil Shutting Down Science Without Borders. Available online: https://monitor.icef.com/2017/04/brazil-shutting-science-without-borders/ (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- Walker, P. International student policies in UK higher education from colonialism to the coalition: Developments and consequences. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 2014, 18, 325–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BBC News. Currency Depreciation: Nigerian Students Forced out of UK for Tuition Default. BBC News. 22 May 2024. Available online: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/c888926qx58o (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- Dilshad, M.N. Understanding the Impact of the Financial Crisis on Higher Education in the United Arab Emirates and Meeting the Challenges Through an International Comparative Study. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varghese, N.V. Globalization, Economic Crisis and National Strategies for Higher Education Development; UNESCO-IIEP: Paris, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson, J. International Student Numbers Could Fall a Lot Further Yet. Wonkhe. 23 May 2024. Available online: https://wonkhe.com/blogs/international-student-numbers-could-fall-a-lot-further-yet/ (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- Nicol, L. Students Have Been Sold a Dream by Agents and Universities. Univ. World News. 5 February 2025. Available online: https://www.universityworldnews.com/post.php?story=20250204143654905 (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Ansell, M. Refocus for UK Higher Education as International Student Numbers Expected to Fall. British Council. 8 February 2024. Available online: https://www.britishcouncil.org/about/press/refocus-uk-higher-education-international-student-numbers-expected-fall (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Sokolova, T. The Shifting Landscape of Study Abroad Destinations. Available online: https://www.educations.com/higher-education-news/the-shifting-landscape-of-study-abroad-destinations (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Weimer, L.; Barlete, A. The rise of nationalism: The influence of populist discourses on international student mobility and migration in the UK and US. In Universities as Political Institutions; Weimer, L., Nokkala, T., Eds.; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 33–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, R. Sharp Fall in International Applicants Wanting to Study at UK Universities. The Guardian. 8 August 2024. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/education/article/2024/aug/08/sharp-fall-in-international-applicants-wanting-to-study-at-uk-universities (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Blake, G. Reduced International Student Numbers are a Much Bigger Problem than You Think. High. Educ. Policy Inst. 3 September 2024. Available online: https://www.hepi.ac.uk/2024/09/03/reduced-international-student-numbers-are-a-much-bigger-problem-than-you-think/ (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Cavanagh, M.; Glennie, A. International Students and Net Migration in the UK; IPPR: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wakeling, P.; Lopes, A.D.; Mateos-González, J.L. Brexit as Revelatory Policy Shock: What Can We Learn about International Student Mobility from Changes in EU Student Mobility to the UK after Brexit? Eur. J. High. Educ. 2025, 1, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binsardi, A.; Ekwulugo, F. International marketing of British education: Research on the students’ perception and the UK market penetration. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2003, 21, 318–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogden, K. A Decline in Foreign Students and Higher Costs Create a Perfect Storm for Scottish Universities. Inst. Fiscal Stud. 19 November 2024. Available online: https://ifs.org.uk/articles/decline-foreign-students-and-higher-costs-create-perfect-storm-scottish-universities (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Watermeyer, R.; Crick, T.; Knight, C.; Goodall, J. COVID-19 and digital disruption in UK universities: Afflictions and affordances of emergency online migration. High. Educ. 2021, 81, 623–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkins, S.; Balakrishnan, M.S.; Huisman, J. Student choice in higher education: Motivations for choosing to study at an international branch campus. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 2012, 16, 413–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, S.; Huisman, J. International student destination choice: The influence of home campus experience on the decision to consider branch campuses. J. Mark. High. Educ. 2011, 21, 61–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taix, C.; AFP. U.K. Universities Brace for Financial “Crunch” as Brexit and Visa Squeeze Drive International Students Away. Fortune. 11 November 2024. Available online: https://fortune.com/europe/2024/11/11/uk-universities-face-funding-crunch-brexit-plunge-international-student-numbers/ (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- ICEF Monitor. International Enrolment Declines Pressuring UK Universities This Year, With One in Three Facing Significant Financial Challenges. ICEF. 24 July 2024. Available online: https://monitor.icef.com/2024/07/international-enrolment-declines-pressuring-uk-universities-this-year-with-one-in-three-facing-significant-financial-challenges/ (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Dennis, M.J. The impact of geopolitical tensions on international higher education. Enroll. Manag. Rep. 2022, 26, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Union of Students UK. Dismantle the Hostile Environment: NUS Responds to Decline in International Student Applications. NUS UK. 12 September 2024. Available online: https://www.nus.org.uk/international-student-application-figures (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- TPP Recruitment. Student Recruitment: Current Challenges and Finding New Markets. Available online: https://www.tpp.co.uk/resources/blog/student-recruitment--current-challenges-and-finding-new-markets/ (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Laker, B. Major Blow to U.K. Universities: The Decline of International Students. Forbes. 28 January 2024. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/benjaminlaker/2024/01/28/major-blow-to-uk-universities-the-decline-of-international-students/ (accessed on 1 March 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hunaiti, Z.; Sultan Altamimi, L. Post-2024 UK International Student Supply Chain Challenges. Encyclopedia 2025, 5, 132. https://doi.org/10.3390/encyclopedia5030132

Hunaiti Z, Sultan Altamimi L. Post-2024 UK International Student Supply Chain Challenges. Encyclopedia. 2025; 5(3):132. https://doi.org/10.3390/encyclopedia5030132

Chicago/Turabian StyleHunaiti, Ziad, and Lubna Sultan Altamimi. 2025. "Post-2024 UK International Student Supply Chain Challenges" Encyclopedia 5, no. 3: 132. https://doi.org/10.3390/encyclopedia5030132

APA StyleHunaiti, Z., & Sultan Altamimi, L. (2025). Post-2024 UK International Student Supply Chain Challenges. Encyclopedia, 5(3), 132. https://doi.org/10.3390/encyclopedia5030132