1. Introduction

Scholarly interest in teacher resilience has grown substantially over the last years, reflecting increased recognition of the complex and frequently demanding nature of the teaching profession [

1]. Over time, the understanding of teacher psychological resilience has evolved from being viewed as an innate, unchangeable quality to being recognized as a complex and dynamic process involving constructive responses to persistent challenges [

2]. Rather than merely coping with difficulties, resilient educators actively thrive in their roles by utilizing personal strengths and drawing on supportive environments [

3]. From this perspective, teacher resilience involves the dynamic interplay between personal attributes (e.g., perseverance, optimism, motivation), social parameters (e.g., relationships with colleagues, interactions with students), and physical conditions (e.g., school infrastructure) in managing risk factors that emerge within the school context.

Drew and Sosnowski [

4] developed a framework highlighting three core aspects of teacher resilience. First, resilient educators are strongly connected to their school communities and guided by a clear sense of mission, which helps them manage challenges and take advantage of favorable conditions. Second, they exhibit psychological flexibility, approaching uncertainty with openness and transforming setbacks into learning experiences, thereby preserving autonomy and emotional equilibrium amid diverse influences. Finally, they cultivate and depend on supportive interpersonal relationships with peers, students, and leadership as essential sources of encouragement and resilience during times of stress.

The factors that safeguard and strengthen teachers’ psychological resilience are commonly grouped into two broad categories: internal (personal attributes) and external (environmental supports). Mansfield et al. [

5] describe the internal category as consisting of two main elements: (a) the personal strengths and motivational factors teachers possess, and (b) the methods they use to activate and implement those strengths. In contrast, external protective elements relate to the social and organizational environment. Gu [

6] highlights three critical relational contexts within schools that shape teachers’ professional lives: their interactions with students, colleagues, and connections with school leadership. Support systems outside of the school, such as family, friendships, religious affiliations, and community ties, also play an essential role in fostering resilience, acting as buffers against occupational stress [

7].

Drawing from extensive empirical work, Mansfield and colleagues [

8] developed a holistic, four-part model that captures the core components of teacher resilience. This framework sees resilience as a multifaceted concept, shaped by the dynamic interrelation of personal qualities and professional demands. The

professional component refers to classroom-related competencies, such as planning, instructional strategies, and self-reflection, often cultivated through formal teacher training. The

emotional component involves managing the psychological pressures of the job, including stress regulation and emotional coping skills. The

motivational component addresses inner psychological drivers, like confidence in one’s teaching abilities, a strong commitment to growth, and perseverance in adversity. Finally, the

social component emphasizes relational skills within the workplace, such as forming supportive professional relationships, asking for assistance when needed, and accepting constructive feedback.

However, it is essential to establish a clear conceptual distinction between the construct of resilience itself and the protective factors that facilitate it. Resilience is better perceived as a dynamic, process-oriented capacity that enables individuals to adapt positively, recover, and grow in response to adversity. In contrast, resilience protective factors, whether internal (e.g., personal traits, coping strategies) or external (e.g., social support, institutional resources), serve as antecedents or enabling conditions that nurture and sustain this adaptive capacity, rather than constituting resilience per se.

Drawing on advancements in the resilience literature, various assessment instruments have been developed to evaluate resilience within educational settings, aiming to capture its multifaceted dimensions as they pertain specifically to teachers. This review provides a critical examination of the current tools used to assess teacher resilience and/or its protective factors. It focuses on their underlying concepts, psychometric soundness, and suitability for various educational environments, providing a thorough overview that can guide future research, policy development, and interventions focusing on enhancing resilience among educators.

2. Method and Procedure

The present study followed a scoping review procedure to identify, select, and analyze instruments specifically developed or adapted to assess teacher resilience, aiming to identify research gaps and types of psychometric evidence available. A review protocol was created, which is available on the OSF repository (

https://osf.io/xnjwb/?view_only=0a40acf03cd247b5b28e6fb02d9b5ea9 accessed on 21 July 2025; DOI:

https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/XNJWB). To ensure methodological rigor and relevance, specific eligibility criteria were applied in the selection of sources of evidence. First, only peer-reviewed empirical studies published between 2003 and 2025 were included. This timeframe was chosen to reflect the development of teacher resilience as a distinct research area, beginning with foundational instruments and extending to more recent, context-sensitive tools. Second, the review was limited to publications written in English to maintain consistency in the interpretation of psychometric terminology and to ensure accessibility of methodological details. While this may introduce language bias, it allowed for a more reliable synthesis of findings. Third, only studies that focused explicitly on the development, validation, or cultural adaptation of resilience instruments designed for teachers—in-service, pre-service, special education, or English as a Foreign Language (EFL) educators—were considered. This criterion ensured that the instruments reviewed were tailored to the unique demands of educational contexts, rather than general population resilience measures. Finally, gray literature, such as unpublished dissertations, reports, or non-peer-reviewed conference proceedings, was excluded, as these sources may lack rigorous methodological appraisal and standardized psychometric reporting. Collectively, these criteria aimed to enhance the quality, clarity, and applicability of the scoping review’s findings.

A comprehensive electronic search was conducted across major academic databases, including PsycINFO, ERIC, Scopus, and Web of Science, to identify peer-reviewed studies related to the development, validation, or adaptation of psychometric instruments assessing teacher resilience. The search strategy combined three key conceptual domains: the target population (e.g., “teacher resilience,” “resilient teacher*”), the nature of the instrument (e.g., “scale,” “instrument,” “questionnaire,” “assessment”), and the type of methodological focus (e.g., “development,” “validation,” “psychometric,” “adaptation”). Boolean operators and truncation symbols were used to enhance the sensitivity of the search. The following search string was applied to the title, abstract, and keywords: (“teacher resilience” OR “resilient teacher*” OR “teacher* psychological resilience”) AND (“scale” OR “instrument” OR “measure*” OR “questionnaire” OR “assessment” OR “tool”) AND (“development” OR “validation” OR “psychometric” OR “adaptation”). The search was limited to English-language publications, peer-reviewed journal articles, and studies published between January 2003 and May 2025. These parameters were selected to ensure the inclusion of methodologically robust and conceptually relevant sources within a contemporary timeframe.

Data from the included sources of evidence were charted using a structured and pre-calibrated data extraction form, explicitly developed for the purposes of this review. The form was pilot-tested on a subset of studies (n = 3) to ensure the data fields’ clarity, consistency, and relevance, and minor adjustments were made accordingly. Key information extracted included the instrument name, authors, year of publication, target population, theoretical framework, number of items and dimensions, psychometric properties (e.g., reliability, validity), and evidence of cross-cultural or contextual applicability. The authors conducted the charting process independently to enhance reliability and minimize bias. Discrepancies in data extraction were resolved through discussion, and where necessary, a third reviewer was consulted to reach consensus. No direct contact with original study authors was required, as all relevant data were available within the published articles. This systematic approach ensured the comprehensive and consistent extraction of key variables relevant to the review objectives.

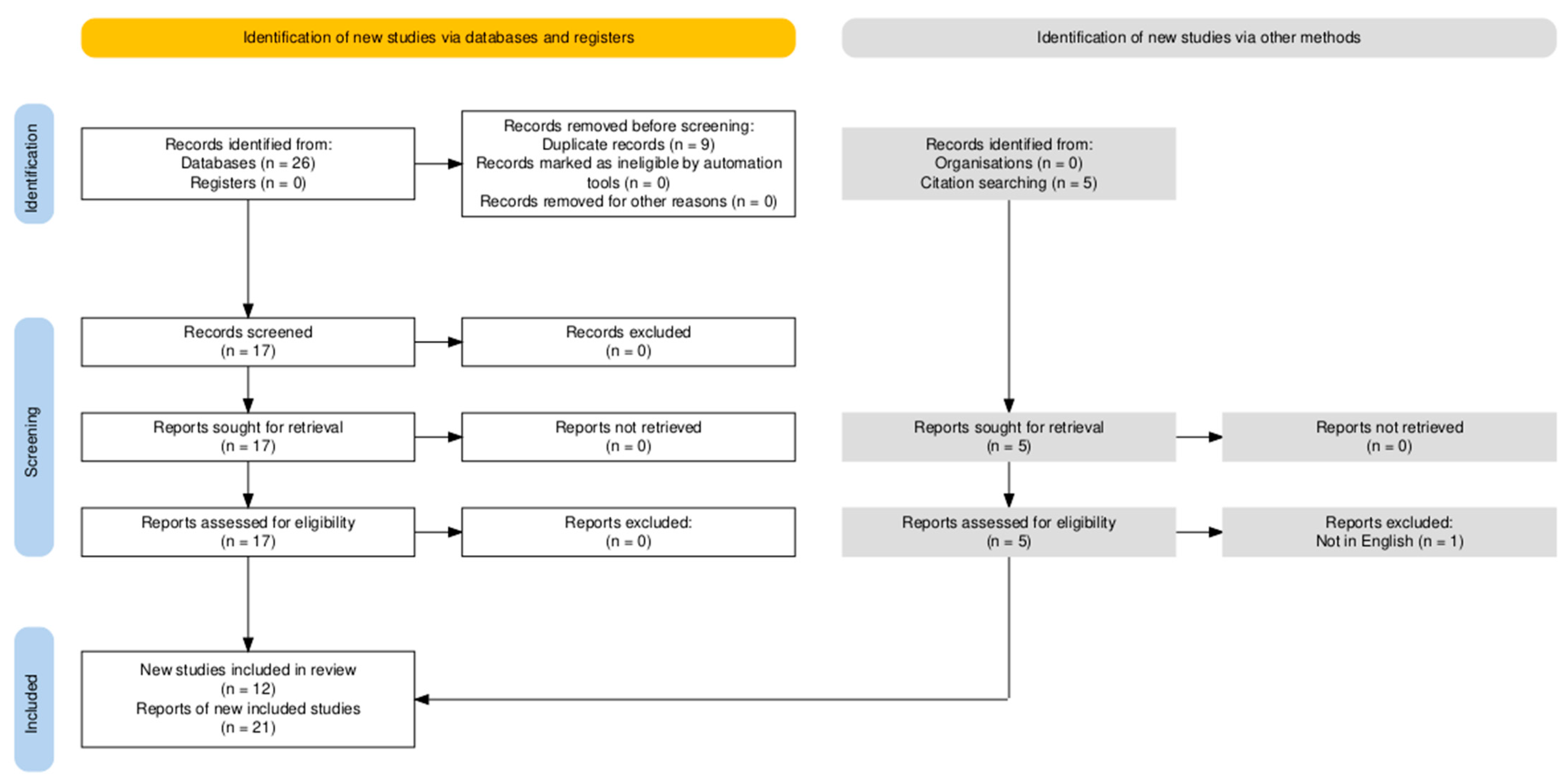

Figure 1 presents a PRISMA flow diagram that illustrates the scoping review procedure followed for the identification, screening, eligibility assessment, and final inclusion of studies concerning creating resilience scales addressed to teachers. The selected instruments were then examined in terms of their theoretical framework, structure, psychometric properties (e.g., reliability, validity), and practical relevance to educational settings.

All charted data were managed using Microsoft Excel, allowing for systematic organization and comparison of variables across studies. A narrative synthesis was employed to summarize key findings, structured around thematic categories such as instrument type, dimensional structure, psychometric quality, and population specificity. Additionally, a tabular summary was developed to provide a side-by-side comparison of the included instruments. The following variables were extracted from each included study: (1) instrument name, to identify and reference each scale; (2) author(s) and year of publication, to establish the timeline of instrument development; (3) target population, specifying whether the tool was designed for in-service, pre-service, EFL, or special education teachers; (4) theoretical framework, indicating the conceptual basis underlying each instrument; (5) number of items, providing information on the scale’s length; (6) measured dimensions, reflecting the structure and conceptual scope of the instrument; (7) psychometric properties, including internal consistency (e.g., Cronbach’s α), construct validity, and factorial structure; (8) cross-cultural validation or adaptation, to assess generalizability across contexts. These variables were selected to ensure a comprehensive understanding of both the conceptual and empirical robustness of each instrument.

Table 1 provides a concise overview of key psychometric instruments developed to assess teacher resilience. The table summarizes critical information for each instrument, including developers, year of publication, target population, measured dimensions, and number of items. This comparative snapshot facilitates a quick understanding of how each tool conceptualizes and operationalizes teacher resilience. A more detailed narrative presentation of these instruments follows, offering more profound insights into their theoretical frameworks, methodological features, psychometric strengths, cross-cultural validation, and empirical applications. The instruments are presented in chronological order based on their year of development, beginning with the earliest.

While this review aims to provide a comprehensive synthesis of resilience instruments for teachers, certain limitations should be acknowledged. First, the inclusion criteria were limited to peer-reviewed studies published in English over the past two decades, which may have introduced language and publication biases. Second, the review did not include gray literature, such as that on instruments found in dissertations not published in peer-reviewed journals, government reports, or non-indexed sources, which may contain relevant instruments or validation data. Finally, in accordance with the objectives of a scoping review, a formal critical appraisal of methodological quality or risk of bias was not performed, as the primary aim was to map the extent, nature, and characteristics of available instruments rather than to evaluate study rigor or exclude evidence based on quality. However, select indicators of psychometric robustness, such as internal consistency reliability (e.g., Cronbach’s alpha), construct and factorial validity, and evidence of cross-cultural adaptation, were noted and descriptively reported. These psychometric indicators served to highlight relative strengths and limitations across instruments and inform interpretive comments within the narrative synthesis, but they did not influence study inclusion or weighting in the review findings. These constraints may limit the scope of identified tools and should be considered when interpreting the generalizability and completeness of the findings.

3. Instruments Assessing Teachers’ Resilience

3.1. The Multidimensional Teachers’ Resilience Scale

The Multidimensional Teachers’ Resilience Scale (MTRS), developed by Mansfield and Wosnitza [

9], is a psychometrically grounded instrument designed to capture the complex and multifaceted nature of resilience within the teaching profession. Comprising 26 items, the scale assesses four distinct but interrelated dimensions: professional resilience, emotional competence, social competence, and motivation. These dimensions reflect key personal and contextual capacities that enable teachers to adapt effectively to occupational stressors and challenges. The MTRS offers a comprehensive framework for evaluating resilience as a dynamic construct, grounded in individual attributes and social–environmental factors relevant to educational settings. This perspective aligns with the multidimensional conceptualization of resilience, as articulated by Beltman [

10], which emphasizes the dynamic and multifaceted nature of the construct. It underscores the intricate interplay between personal and contextual factors that shape the development and expression of resilience in educational settings.

The MTRS has been widely employed in international research, demonstrating its relevance across diverse educational contexts [

11,

12,

13,

14]. These studies generally report satisfactory levels of internal consistency, supporting the reliability of the scale. However, findings regarding the factorial structure of the MTRS have been mixed, indicating potential cultural variability in how resilience is conceptualized and manifested among teachers. For instance, Panagiotidou et al. [

11] found that some items were associated with their corresponding latent variable. Similarly, Peixoto et al. [

15], using a Portuguese sample, proposed a refined 13-item version of the scale, also comprising four factors, but with modifications to the original structure. These variations suggest that while the MTRS offers a valuable framework, its application may require cultural adaptation to ensure conceptual and structural validity across different educational systems.

Furthermore, it is noteworthy that the MTRS primarily emphasizes the assessment of internal protective factors related to individual resilience, such as emotional competence, motivation, and professional efficacy, while offering limited consideration of external or environmental influences. This focus on intrapersonal dimensions may restrict the scale’s capacity to fully capture the ecological and systemic factors, such as school climate, collegial support, and leadership practices, that have been found to play a critical role in fostering or hindering resilience among teachers. As such, while the MTRS provides valuable insights into personal resilience resources, its applicability could be enhanced through the integration of contextual variables that reflect the broader socio-professional environment in which teachers operate.

3.2. The Teachers’ Resilience Scale (TRS)

The Teachers’ Resilience Scale (TRS), developed by Daniilidou and Platsidou [

16], was specifically designed to provide a comprehensive assessment of both personal and environmental protective factors that contribute to teachers’ resilience. Unlike instruments that focus predominantly on individual-level attributes, the TRS adopts an integrative approach by incorporating elements from two well-established resilience measures originally developed for the general adult population. In particular, it draws upon the Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale [

17], integrating the subscales of personal competence and persistence, as well as spiritual influences, alongside subscales from the Resilience Scale for Adults [

18], including family cohesion and social competence/peer support. This synthesis reflects an effort to tailor resilience assessment to the specific demands and contextual realities of the teaching profession, acknowledging the interplay between individual strengths and the support systems embedded in teachers’ personal and professional environments.

Empirical research has confirmed that the TRS is a psychometrically sound instrument for assessing both personal and environmental protective factors of resilience among teachers. Validation studies have demonstrated the reliability and construct validity of this instrument across diverse cultural contexts. In Greece, the scale has shown strong psychometric properties in samples of in-service teachers [

19,

20]. Moreover, its cross-cultural applicability has been supported by studies conducted in countries such as South Africa and the United States [

21], Iran [

22], and Poland [

23]. Boczkowska et al. [

24] further confirmed the cultural invariance of the TRS, demonstrating that the scale maintains consistent psychometric properties across diverse cultural contexts. Their findings suggest that the TRS can be reliably used to assess resilience among teachers across different countries, supporting meaningful cross-cultural comparisons. These findings highlight the TRS’s capacity to capture a broad spectrum of resilience-related factors across various educational systems and cultural settings, underscoring its value as a comprehensive and adaptable assessment tool.

However, it is essential to acknowledge certain limitations of the TRS. As a synthesis of two pre-existing scales developed initially for the general adult population, the TRS includes several items phrased in broad, non-specific terms and may not fully capture the unique contextual demands of the teaching profession. For instance, items such as “Meeting new people in my workplace is something I am good at” or “During challenging times, my family maintains a positive outlook for the future” assess general social and familial support, but do not explicitly address the nuanced and profession-specific challenges teachers face within school settings. This may limit the scale’s sensitivity to contextually embedded resilience factors, such as support from school leadership or coping strategies specific to classroom stressors. Additionally, recent evidence suggests that full metric and scalar invariance are not entirely supported, indicating that cross-cultural comparisons using the TRS should be interpreted with caution [

24].

3.3. Teachers’ Protective Factors of Resilience Scale

The Teachers’ Protective Factors of Resilience Scale (TPFRS), developed by Daniilidou and Platsidou [

25], represents an advanced effort to capture a more comprehensive and context-sensitive profile of teacher resilience. Building on insights from earlier instruments, namely the Multidimensional Teachers’ Resilience Scale [

9] and the Teachers’ Resilience Scale [

22], as well as qualitative data gathered by Daniilidou [

26], this scale was created using the Item Response Theory method. It encompasses 29 items that span six protective factors. These are categorized into three internal/personal dimensions (values and beliefs, emotional and behavioral competence, and physical well-being) and three external/environmental dimensions (relationships within the school context, relationships outside the school context, and the legislative framework). Notably, the scale encompasses a broader range of protective dimensions than most existing resilience instruments in the educational field, offering a multidimensional and ecologically grounded approach that recognizes the systemic nature of teacher resilience.

Daniilidou and Platsidou [

27] validated the factorial structure and internal reliability of the Teachers’ Protective Factors of Resilience Scale (TPFRS) in a large sample of 964 Greek primary and secondary school teachers, also confirming its construct and discriminant validity. These findings suggest that the TPFRS is a theoretically grounded and psychometrically sound instrument within the Greek educational context. However, as a newly developed scale, its broader applicability remains to be established. To date, there is no evidence of further validation studies or examinations of its cultural invariance in other educational systems. Therefore, while the TPFRS offers a comprehensive framework encompassing a wide array of personal and contextual resilience factors, its utility for international research and cross-cultural comparison requires further empirical investigation.

3.4. Vietnam Teachers’ Resilience Scale

The Vietnam Teachers’ Resilience Scale (VITRS), developed by Trang and Thang [

28], is a context-specific instrument designed to capture the unique characteristics of teacher resilience within Southeast Asian and, particularly, Vietnamese educational settings. Comprising 20 items, the VITRS assesses resilience across four core dimensions: social, professional, emotional, and motivational. While this structure conceptually aligns with the framework of the Multidimensional Teachers’ Resilience Scale (MTRS), the developers of the VITRS introduced culturally relevant adaptations to accurately reflect the socio-educational realities and professional expectations of Vietnamese teachers. These modifications improved the scale’s contextual validity, ensuring that the instrument aligns with the lived experiences of educators in the region and addresses resilience in meaningful and applicable ways within this cultural framework.

The VITRS was administered to a sample of 755 Vietnamese high school and university teachers, with the findings supporting its factorial structure, internal consistency, and discriminant validity [

28]. As such, the scale presents a promising tool for assessing teacher resilience within the Vietnamese educational context and potentially across other Southeast Asian countries that share similar cultural and systemic characteristics. Nevertheless, its broader applicability remains to be fully determined. To date, there is a lack of additional validation studies or cross-cultural examinations of the scale’s structural integrity in other Southeast Asian educational settings. Moreover, a review of the scale items, as presented by its creators, suggests that the majority are framed in general terms and may not reflect uniquely Vietnamese sociocultural or educational features. This raises questions about the extent to which the VITRS functions as a culturally specific instrument, despite its intended contextual orientation.

3.5. Teacher Resilience Instrument

The Teacher Resilience Instrument (TRI), developed by Abubakar et al. [

29], comprises 17 items distributed across four dimensions: self-reliance, positive outlook, determination, and equanimity. The development of the TRI was informed by several widely used resilience measures, including the Resilience Scale [

30] and the Workplace Resilience Instrument [

31], reflecting an effort to integrate key aspects of resilience relevant to professional contexts. A notable strength of the TRI is its inclusion of protective factors, such as equanimity and determination, that are less commonly emphasized in other teacher-specific instruments, thereby contributing to a more differentiated understanding of resilience. However, a significant limitation lies in the absence of a clearly articulated theoretical framework guiding the selection and adaptation of items to the teaching profession. This weakens the conceptual coherence of the scale and raises concerns regarding its specificity and validity as a measure of teacher resilience.

The TRI was administered to a sample of 380 secondary school teachers in Bauchi State, Nigeria, using a multistage cluster sampling procedure. The results supported the scale’s factorial structure, providing initial evidence for its construct validity [

29]. However, the relatively small sample size limits the generalizability of the findings. Furthermore, two of the four subscales demonstrated marginal internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.67), raising concerns about the reliability of certain dimensions. To date, no replication studies have been conducted, and there is no available evidence regarding the instrument’s discriminant validity. These limitations suggest that while the TRI introduces some novel dimensions of resilience, further refinement and validation are necessary before it can be reliably applied across diverse educational contexts.

3.6. Teachers’ Resilience Scale for Sustainability

The Teachers’ ICT/MeEfS Resilience Scale, developed by Makrakis [

32], is a validated instrument designed to assess educators’ resilience in integrating sustainability principles and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) into their pedagogical practices through the use of Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) and metaverse-based learning environments. The scale comprises 10 items and evaluates two core dimensions: personal competence in applying ICT and metaverse tools for sustainability-oriented education, and reflexive teaching practice, which encompasses critical reflection and transformative pedagogical action. Its development was grounded in an extensive review of the relevant literature and theoretical frameworks pertaining to sustainability education, teacher agency, and transformative learning, ensuring a conceptually robust foundation for measuring this emerging aspect of teacher resilience.

The scale was tested using a large sample of 1815 in-service teachers from Indonesia, Malaysia, and Vietnam. Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) supported a two-factor structure consistent with the instrument’s theoretical framework. The scale demonstrated excellent internal consistency, indicating strong reliability across both dimensions. Furthermore, significant correlations with related constructs, including ICT self-efficacy and transformative teaching beliefs, established predictive validity. While the Teachers’ ICT/MeEfS Resilience Scale introduces a novel and timely approach to assessing teacher resilience within the context of sustainability and digital innovation, it remains a newly developed instrument and, as such, requires further validation in diverse educational and cultural settings to confirm its generalizability and robustness.

3.7. Teacher Resilience Inventory

Chen [

33] developed the Teacher Resilience Inventory to re-conceptualize teacher resilience. In its final form, the scale comprises 20 items and evaluates five resilience dimensions: physical, emotional, psychological, social, and spiritual resilience. The scale’s development was informed by a socioecological framework, with item construction grounded in qualitative data derived from interviews with 25 teachers.

The scale was tested in two samples of Chinese teachers (n = 292 and 575, respectively), and the results confirmed the suggested factorial structure. The scale demonstrated good internal consistency, indicating strong reliability across dimensions and good convergent and discriminant validity. Further studies [

34] have validated the factorial structure and reliability of the instrument. Initial evidence shows promising results. However, the participating teachers in the aforementioned studies originated from convenience samples from one district in China. Therefore, as a newly developed instrument, it requires further validation in diverse educational and cultural settings to confirm its generalizability and robustness. In addition, although the scale’s creator advocates that it was developed to re-image resilience, the ways in which it meaningfully diverges from existing instruments remain unclear.

3.8. Iranian Teachers’ Resilience Scale

The Iranian Teachers’ Resilience Scale (ITRS), developed by Latifi et al. [

35], is an adapted version of the Vietnam Teachers’ Resilience Scale (VTRS) by Trang and Thang [

28], tailored to the sociocultural and educational context of Iran. Like its predecessor, the ITRS measures teacher resilience across four core dimensions: social, professional, emotional, and motivational. The scale was validated on a sample of 700 middle and high school teachers in Iran. Evidence for convergent validity was established, and the instrument demonstrated satisfactory levels of internal consistency. While confirmatory factor analysis supported the proposed four-factor structure, a three-factor solution emerged as the most stable, suggesting potential overlap or redundancy among dimensions. As a newly developed instrument, the ITRS shows promise but requires replication and further validation in diverse Iranian samples to establish its robustness and generalizability.

4. Instruments Assessing Pre-Service Teachers’ Resilience

The Academic Resilience Scale for Preservice Teachers

The Academic Resilience Scale for Preservice Teachers, developed by Dalimunthe et al. [

36], is a psychometrically validated instrument tailored to assess resilience in preservice teachers across diverse academic domains. Drawing on resilience theory and building upon established instruments, such as the Academic Resilience Scale [

37] and the Resilience at University scale [

38], this scale comprises 14 items that capture seven core internal dimensions of resilience: composure, commitment, control, coordination, empathy, perseverance, and adaptability. These constructs reflect the intrapersonal resources preservice teachers rely on to navigate academic adversity and professional preparation challenges.

The scale has been administered to various samples of preservice teachers in Indonesia [

39,

40], and its psychometric properties have demonstrated strong construct validity and internal consistency. By focusing explicitly on the preservice teacher population, the scale addresses a significant gap in the academic resilience literature, offering a contextually relevant tool for educational research and practice. However, its broader applicability is constrained by the lack of cross-cultural validation studies. Moreover, each of the seven factors is represented by only two items, raising methodological concerns regarding content coverage and whether the items sufficiently capture the complexity of the underlying latent constructs.

5. Instruments Assessing EFL Teachers’ Resilience

5.1. English Language Teacher Resilience Instrument

The English Language Teacher Resilience Instrument (ELT-RS), developed by Shirazizadeh and Abbaszadeh [

41], is a context-specific tool designed to assess the resilience of English Language Teachers (ELTs). The instrument comprises 35 items distributed across five theoretically grounded dimensions: internal motivations, social skills, emotional management, pedagogical skills, and contextual support. Item development was informed by qualitative data from semi-structured interviews with 14 Iranian English as a Foreign Language (EFL) teachers and a comprehensive review of the literature on teacher resilience. The scale was subsequently validated with a sample of 224 ELTs, demonstrating satisfactory internal consistency and preliminary psychometric soundness. Despite its promising structure and relevance to the ELT context, the ELTRS remains a recently developed instrument and, therefore, requires further empirical validation across different educational and cultural settings to establish its generalizability and construct robustness.

5.2. EFL Teacher Resilience Scale

The EFL Teacher Resilience Scale (EFL-TRS), developed by Liu et al. [

42], was designed to address the lack of targeted instruments measuring resilience specifically among English as a Foreign Language (EFL) teachers. The scale comprises 22 items encompassing four key dimensions: professional, emotional, social, and cultural resilience. Notably, the inclusion of the cultural dimension represents an innovative addition, capturing the unique sociocultural challenges that EFL teachers often encounter in diverse instructional settings. The instrument was validated using a large and representative sample of 3992 Chinese high school English as a Foreign Language (EFL) teachers, with findings indicating good psychometric properties, including internal consistency and construct validity. Although the EFL-TRS shows considerable promise as a robust and context-sensitive measure of teacher resilience, further research is needed to examine its applicability across different cultural and educational contexts and to establish its measurement invariance through cross-cultural validation studies.

6. Instruments Assessing Special Education Teachers’ Resilience

Special Education Career Resilience Scale

The Special Education Career Resilience Scale (SECRS) was developed by Sotomayor [

43], comprising 71 items. It was developed as a composite instrument incorporating four existing scales: two assessing resilience, one measuring coping behaviors, and one evaluating perceived administrative support. The aim was to align item content with the four domains of the Career Resiliency Framework: theme acceptance, support for self-awareness, conversion, and connectedness. The development process involved multiple validation steps, including cognitive interviews, expert review, and pilot testing. The final version was administered to a sample of 567 special education teachers, including both continuing and non-continuing teachers, from suburban and rural school districts. However, exploratory factor analysis indicated that a transparent and interpretable factor structure could not be established for the overall instrument. Further analysis of individual subscales revealed that only the theme acceptance subscale yielded a coherent two-factor structure.

The SECRS was explicitly developed to assess the level of resilience among special education teachers, making it a unique contribution, as it is the only instrument to date explicitly tailored to this professional subgroup. Its targeted focus addresses the distinct challenges faced by special educators, which are often underrepresented in general teacher resilience research. However, despite its conceptual relevance, the instrument has seen limited empirical application in the literature [

44]. Initial psychometric analyses revealed concerns regarding the scale’s overall construct validity. These findings underscore the need for substantial revision and refinement, yet no updated or revised version of the SECRS has been reported in subsequent research.

7. Conclusions

This review provides a comprehensive synthesis of existing instruments designed to assess resilience among teachers, highlighting both their conceptual foundations and psychometric robustness. The collective evidence underscores a clear progression in the field, from early tools that emphasize intrapersonal resilience traits to more recent, ecologically sensitive instruments that integrate systemic and contextual dimensions.

Among the earliest contributions, the Multidimensional Teachers’ Resilience Scale (MTRS) provided a foundational model by delineating core psychological competencies. However, its limited engagement with environmental factors restricts its comprehensiveness. Following attempts, such as the TRS and the TPFRS, represent significant strides in addressing this gap by integrating personal and environmental protective factors. The TRS, in particular, has been validated across diverse cultural contexts, suggesting a degree of cross-cultural robustness that enhances its utility for international comparative studies.

Nevertheless, the trend of adapting resilience measures from general populations (e.g., CD-RISC, RSA) remains prevalent, which introduces both strengths and limitations. While such adaptations ensure conceptual continuity with broader resilience research, they may also lead to a lack of sensitivity to the unique stressors and protective resources inherent in teaching professions. Instruments such as the VITRS, ITRS, and TRI illustrate these challenges. Despite efforts to contextualize resilience to local educational settings, they often lack a clearly articulated theoretical framework tailored to teachers’ lived experiences.

Newer scales, including the TPFRS and the Teachers’ ICT/MeEfS Resilience Scale, mark a promising direction by addressing the ecological complexity of resilience and/or incorporating emerging educational domains, such as sustainability and digital transformation. These tools recognize that teacher resilience is not merely an individual trait but a dynamic interplay between internal capacities and external supports embedded in specific sociopolitical and institutional contexts.

Despite these advances, significant limitations persist. Many instruments suffer from methodological and psychometric issues (e.g., a limited number of items per factor, marginal reliability) and limited cross-cultural validation, relying on psychometric analyses conducted within narrow national or demographic boundaries. Additionally, some scales, particularly those developed for subpopulations, such as EFL or special education teachers, remain in the early stages of empirical testing, with unclear construct validity or generalizability.

8. Future Directions

Despite the substantial progress in developing resilience assessment tools for teachers, future research must address several critical gaps to advance the field conceptually and methodologically. One key direction involves the development of culturally grounded and context-sensitive instruments. Although some recent scales, such as the Vietnam Teachers’ Resilience Scale (VITRS) and the Iranian Teachers’ Resilience Scale (ITRS), attempt to tailor resilience assessment to specific national contexts, their conceptual frameworks often remain rooted in Western-centric models. This may be due to a predominant focus on linguistic translation rather than deeper cultural adaptation. However, effectively adapting resilience scales for teachers requires more than mere translation; it demands ensuring that the construct of resilience reflects culturally specific experiences of adversity in teaching, as well as contextually relevant protective factors. In this context, using qualitative methods, such as collecting teacher narratives and conducting focus groups, is recommended to capture culturally grounded expressions of resilience and identify contextually relevant protective factors. Scale items could be reviewed and modified to reflect these contextual realities, followed by careful translation and cognitive interviewing to detect misunderstandings. Iterative refinement with input from educators and cultural experts could further enhance relevance. Finally, incorporating culturally specific dimensions, such as community values, socio-political contexts, and culturally rooted coping strategies, could strengthen the sensitivity of the instruments. These approaches could ensure that instruments reflect local meanings and expressions of resilience and its protective factors, enhancing both ecological validity and cross-cultural relevance.

Moreover, another pressing limitation of current teacher resilience instruments is their limited alignment with real-world educational contexts. Teacher resilience does not develop in isolation; rather, it is shaped by institutional factors such as school leadership, organizational climate, policy support, and access to professional development. Many scales are developed in controlled academic settings, often lacking direct input from practitioners or relevance to specific school-based challenges. This detachment impedes the translation of findings into actionable interventions within schools. Instruments like the Teachers’ Protective Factors of Resilience Scale (TPFRS) and the Teachers’ ICT/MeEfS Resilience Scale have made promising strides by integrating contextual variables. However, additional research is needed to explore how these external factors interact with personal competencies to influence resilience trajectories. Future scale development could emphasize the inclusion of systemic and environmental dimensions of resilience, adopt a practice-informed approach, and engage educators, school leaders, and stakeholders in co-design processes to ensure ecological validity and practical utility. Ultimately, resilience instruments should be designed not only to assess the construct itself, but also to inform and guide targeted professional development and well-being initiatives that are aligned with the practical realities of the school context.

In addition, a critical limitation in the current body of research on teacher resilience is that most existing measurement tools assess protective factors rather than resilience as a distinct construct. As a result, the focus is often on measuring the conditions that enable resilience, not the dynamic capability to navigate and recover from professional adversity. This methodological gap poses challenges for accurately evaluating resilience and distinguishing between teachers who possess favorable conditions and those who actively demonstrate resilient functioning despite adversity. To advance the field, future research must prioritize the development of measurement tools that reflect the processual and emergent nature of resilience rather than its antecedents alone.

A further recommendation is to validate resilience instruments across a broader range of teacher subgroups and career stages. Most current scales have been tested predominantly with in-service teachers, often neglecting preservice, novice, or special education teachers, who may face distinct challenges requiring tailored assessments. Expanding validation efforts to include such groups would enhance the utility and inclusiveness of resilience measures. Furthermore, establishing measurement invariance across cultural and linguistic groups is essential for enabling valid cross-cultural comparisons. Without rigorous testing of structural equivalence, interpretations of resilience scores across diverse populations remain tentative and potentially misleading.

Moreover, future research should also adopt more advanced psychometric methodologies to strengthen scale validation. Techniques such as Item Response Theory (IRT), as exemplified in the validation of the TPFRS, provide nuanced item-level analyses that extend beyond traditional classical test theory, enabling researchers to assess item functioning across varying levels of the latent trait. Similarly, bifactor modeling can disentangle general resilience factors from specific subdomain variances, thereby clarifying the multidimensionality of resilience constructs. Additionally, network analysis provides a novel framework for exploring the dynamic interrelationships among resilience components, highlighting potential core indicators and bridge constructs within the resilience network. In parallel, involving teachers in the co-design and evaluation of these tools can ensure that they are not only psychometrically sound but also practically meaningful and empowering within real-world educational contexts.

Finally, a critical limitation of the current instruments reviewed is their predominant focus on static, trait-like attributes of resilience, such as emotional competence or motivational drive, rather than on the dynamic processes through which resilience unfolds over time. As resilience is increasingly understood as a context-sensitive and evolving capacity, future assessment tools should adopt longitudinal and process-oriented methodologies. Incorporating temporal dimensions (e.g., repeated measures designs, experience sampling methods) or modeling trajectories of resilience development could better capture its dynamic nature. Furthermore, combining quantitative tools with qualitative data, such as teacher narratives or diaries, may offer richer insights into how resilience is enacted and transformed across professional challenges and career stages.

Collectively, these methodologies, emphasizing cultural relevance, qualitative inquiry, and alignment with educators’ lived realities, can significantly enhance both the psychometric rigor and conceptual depth of teacher resilience instruments. By grounding scale development in culturally and contextually informed frameworks, future research can contribute to the creation of more valid, meaningful, and actionable tools that not only assess resilience but also support teacher well-being and professional growth in diverse educational settings.