Definition

Ladislaus II Jagiełło (1386–1434). Ladislaus II Jagiełło is the founder of the Jagiellonian dynasty that had ruled over Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania (until 1572), Bohemia (1471–1526) and Hungary (1440–1444, 1490–1526). A Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1377, and from 1386 a king of Poland and lord of Lithuania, which he ruled jointly with his cousin Witold (Vytautas), the son of Kęstutis. Five medieval portraits of Jagiełło survive, four of which date from the period of his reign in the Polish–Lithuanian state and one was executed posthumously. The earliest image, on Jagiełło’s Great Seal, was made in connection with his coronation as king of Poland (1386). Two portraits in the Holy Trinity Chapel at the Castle of Lublin (1418) are part of a wall paintings scheme commissioned by the monarch and executed by a team of painters brought from Ruthenia. Furthermore, the sumptuous tomb (before 1430) in Cracow was commissioned by the king. Its top slab bears an effigy of Jagiełło with his suggestively rendered countenance, which undoubtedly reflects the actual facial features of the elderly monarch. An image of the king represented as one of the Three Magi in a panel of an altarpiece in the tomb chapel of Casimir IV Jagiellonian, Jagiełło’s son and his successor on the Polish throne, dates from 1470. The chapel dedicated to the Holy Cross, erected at Cracow Cathedral, was in all likelihood commissioned by Casimir himself and his consort Elizabeth of Austria.

1. Introduction

Jagiełło (Lith. Jogaila), a founder of a new dynasty and its first member on the Polish throne, was one of the Gediminids, stemming from a pagan dynasty that in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries ruled over a vast dominion encompassing the core lands of Lithuania and Ruthenia which, similar to Poland, was threatened by the Teutonic Knights [1]. By asking, in 1385, for the hand of the Polish queen regnant, Hedwig of Anjou (the daughter of Louis of Hungary, king of Poland and Hungary, and granddaughter of Ladislaus the Short, the last-but-one king of Poland from the Piast dynasty), Jagiełło, in an oath taken before the coronation, pledged to adopt the Latin-rite Christianity along with the entire Lithuania, to join Lithuania to Poland and to restore to the Polish Crown the lands lost by Poland to the Teutonic Knights during the reign of the extinct Piast dynasty and the Angevins (for the text of the oath see [2] (p. 2); for the circumstances of Jagiełło’s accession to Polish throne and the commitments made by him at the time see [3,4,5]). Thus, the recovery of the territories lost by the Polish Kingdom in whatever time or whatever way became the guiding principle behind the king’s political and military actions (culminating in the great war with the Teutonic Knights in 1409–1411 and the victorious battle of Grunwald in 1410), and as such found expression in the content of artworks commissioned by Jagiełło.

Historical narratives often presented Jagiełło as an uncouth heathen, uneducated, superstitious and obtuse. This has resulted, to some degree, from the image of the king created by the great Polish chronicler Jan Długosz, who was biased against the Jagiellonians, considering them as ‘aliens’ who replaced the ‘natural lords of Poland’, that is, the Piasts, and did not even hesitate to write slanderous statements and gossip about them in his Annals (for the text of the Annals see [6] (pp. 123–128), and for opinions on Jagiełło formed by writers and chroniclers, his contemporaries, see [7]). The current scholarship shows Jagiełło in a totally different light. He had come from a family whose various representatives professed not only pagan cults but also Orthodox and Catholic Christianity. Byzantine culture was well established at the courts of the Gediminids and, long before the official acceptance of Christianity, the country had ‘consumed ecclesiastical writings and literature’ written both in the Cyrillic and the Latin alphabets [8]. After the baptism, when Jagiełło took the name Ladislaus (Władysław), he not only proved to feel at home within the Latin culture of the Polish Kingdom, but also made his mark as a founder of numerous churches and religious houses, was a sophisticated politician and diplomat, and a patron of the University of Cracow which he, along with Queen Hedwig, re-established in 1400. Jagiełło was additionally a very pious monarch, as attested not only by the documented religious practices in which he participated but also by his abundant artistic patronage (among the most important biographies of Jagiełło see: [3,9,10]; see also a new synthetic treatment of the Jagiellonian dynasty, with a separate chapter dealing with Jagiełło: [11] (pp. 36–46)).

The idea of Jagiełło’s contractual-elective rulership as a successor to the Piast dynasty on the Polish throne and a lord of Lithuania was displayed in the Great Seal (which he had used since shortly after the coronation throughout his entire reign) and on the royal tomb, executed at the time when the monarch tried to secure the succession for his sons (which was supposed to be based on the principle of election by the representatives of the estates, hence the rich figural and heraldic programme of the tomb-chest, partly inspired by the design of the Great Seal). Religious motivations, in turn, among which an important role was played not only by the Christianisation of Lithuania, undertaken by the king, but also his military successes, determined the message of his portraits in Lublin (where Jagiełło was shown in a double role: in prayer, commended by saints to the Christ Child seated on the lap of the enthroned Virgin Mary, and as a triumphant rider mounted on horseback, who receives a cross from an angel). It is highly probable that a decision to represent his likeness as the last of the Three Magi in adoration of the Christ Child in an altarpiece panel in the Chapel of the Holy Cross was dictated by his status of a neophyte king. It attests to the fact that the memory of the dynasty’s founder was kept alive during the reign of Jagiełło’s son and is an expression of the dynastic identity of the Jagiellonians that was taking shape at that time.

2. The Great Seal

The royal chancery of Ladislaus Jagiełło used a few seals, of which only one, the so-called Great Seal of majesty, featured a figurative representation of the monarch, whereas the remaining ones were armorial seals and therefore will be excluded from the present discussion. The Great Seal has survived in over sixty impressions attached to documents from the period 1388–1433, having been in use throughout the entire reign of Jagiełło on the Polish throne. Furthermore, as demonstrated by Irena Sułkowska-Kurasiowa, it was a seal that was most frequently used [12] (p. 51). It is round, and measures 122 mm in diameter, which makes it the largest Polish seal of the period (a later Great Seal of Ladislaus of Varna, the son and first successor of Jagiełło on the Polish throne, modelled on the one under discussion, was of similar dimensions). Its field shows the monarch seated on a throne with a tall back, surmounted by an extensive micro-architectural canopy. The king is shown wearing a crown, with a sceptre in his right hand and an orb surmounted by a cross in his left hand. He is dressed in an ample mantle fastened at the neck, over a close-fitting tunic. The back of the throne is decorated by a fabric, diapered in a lozenge pattern enclosing heraldic Eagles, held by two pages (?) shown in half-length. The image of the monarch seated in majesty is surrounded by seven shields bearing armorial devices of the lands under Jagiełło’s rule, six of which are supported by angels, depicted behind the shields. The arms should be read in alternating order, starting from the topmost dexter side: Eagle (the arms of the land of Cracow and the entire Polish Kingdom), Pogoń (literally ‘pursuit’, Lith. Vytis; the arms of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania), arms of Greater Poland, arms of the Sandomierz land, arms of Cuyavia, arms of the Dobrzyń land and arms of the Crown Ruthenia. The last coat-of-arms is depicted under the king’s feet and is the only one without a supporting angel. The legend on the seal, written in Gothic minuscule letters, reads: “s(erenissimus) wladislavs dei gra(cia) rex polonie n(ec)no(n) t(er)rarv(m) cracovie sa(n)domirie syradie la(nci)cie cuyavie litwanie p(ri)nceps sup(re)m(us) pomoranie rvssieq(ue) d(omi)n(us) (et) h(e)r(e)s (et) c(eterarum)” (the seal was described and published for the first time here: [13] (p. 13–14, table IX) then discussed in [14] (pp. 25–26) and [15] (pp. 44–46); the inscription in the legend has been expanded and transcribed after: [16] (p. 129)) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Great Seal of majesty of Ladislaus Jagiełło, impression in wax, Archiwum Główne Akt Dawnych (The Central Archives of Historical Records in Warsaw), Zb. Dok. perg. 36, image published in: https://agad.gov.pl/?page_id=972 (accessed on 15 December 2021).

The seal, combining an image of the monarch seated in majesty with a set of armorial devices of the state and its lands surrounding the central composition, represents a new type of the Great Seal in Polish sigillography, which had been in use by Polish kings up until the downfall of the First Polish Republic in 1795 (with the exception of the period 1454–1580). The mere image of the monarch seated in majesty, which is the main feature of Jagiełło’s seal, had been part of a sphragistic tradition widespread in Poland since the high Middle Ages (and such an image had appeared on all Polish Great Seals since 1295, that is, since the unification of the Kingdom by Przemysł II after a period of fragmentation) and the extensive architectural throne on which the monarch is seated may be considered a convention continuing from the seals of Louis of Hungary and Hedwig of Anjou. Yet, the composition of Jagiełło’s representation on the seal differs from these earlier examples: unlike in them, here the structure of the throne does not fill most of the central part of the field but is limited to the central axis and is additionally emphasised by the spatially rendered seat and canopy of the throne. The most important innovation is the set of seven armorial shields surrounding the monarch. Although it has antecedents in the Great Seal of Wenceslaus IV of Luxembourg, king of Bohemia (in use from 1363 to 1373), it chronologically precedes the mature compositions of this type appearing on the Great Seals of kings of the Romans and Holy Roman emperors (Sigismund of Luxembourg, Albert II and Frederick III) in the fifteenth century and is considered a device characteristic of the Jagiellonian seals (see [15] (pp. 44–46)).

Innovative composition of the image under discussion reflects the idea of Ladislaus Jagiełło’s contractual-elective rule as the successor to the Piasts on the Polish throne and, at the same time, a sovereign ruler of Lithuania. The set of armorial devices represented on the seal indicates territories forming part of the hereditary territories of the Piast dynasty (the lands of Cracow, Sandomierz, Greater Poland and Cuyavia), along with the coats-of-arms of lands incorporated into the Kingdom or recovered after the death of Casimir the Great, the last king of the Piast dynasty (Ruthenia and the land of Dobrzyń), supplemented by Pogoń, Jagiełło’s personal device, here standing for entire Lithuania, his hereditary land joined with Poland, and for the accomplishments of Jagiełło, a neophyte ruler, in the dissemination of Christianity. The relationship of Jagiełło’s rule with the Piast legacy is additionally underscored by his titles mentioned in the legend, based on the titles of Casimir the Great (see again [15] (p. 290)).

The Great Seal of Ladislaus Jagiełło has not been a subject of an in-depth art-historical investigation so far. Yet, its excellent workmanship is beyond doubt. It is attested by the rendering of such details as the minutely depicted canopy, expressive angel-supporters which lean towards one another as if pulling closer the armorial shields to them and the slender figure of the king covered with a long mantle, flowing around his legs. The figure of the monarch conforms to the canon of such representations, appearing at the time not only in seals but also in manuscript illuminations (similar images of rulers in majesty can be found, for instance, in the so-called Bible of Wenceslaus IV, 1385/90–1402, Vienna, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Cod. 2761). An integral component of this canonical image is also the representation of a bearded face framed on either side by tufts of hair, which significantly differs from the highly individualised features of the king carved several years later on his tomb in Cracow. The author of the seal was apparently not interested in a detailed rendering of the king’s coronation robes; a practice generally accepted in numerous contemporary royal seals. Although the long mantle fastened at the neck represented on the seal (reminiscent of the surviving coronation mantles of the kings of Hungary and Holy Roman emperors) may reflect the actual appearance of the mantle worn by the Polish king for his coronation, the close-fitting tunic and a heavy belt around his waist are elements of the knightly dress widespread in Europe at the time (according to Krystyna Turska, after Jagiełło removed the mantle before the anointment ceremony, his undergarment consisted of a loose tunic fastened around the waist) (for the dress in which Jagiełło was represented on the seal, see [17] (pp. 29–31)).

3. The Wall Paintings in the Holy Trinity Chapel in Lublin

The wall paintings in the Holy Trinity Chapel at the royal castle in Lublin belong to a group of frescoes executed on Jagiełło’s commission by Ruthenian painters in important Catholic churches in the Polish Kingdom. The group encompassed about ten painted schemes, of which—apart from the Lublin paintings—only the decorations in the chancels of the collegiate churches at Wiślica and Sandomierz have survived, along with fragments of paintings in the Chapel of the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary at Cracow Cathedral. All surviving frescoes stand out by the fact that both the entire iconographic programme as well as individual compositions have been perfectly fitted into the architectural structure of the Gothic-style interiors, which makes them unprecedented phenomena in Western European culture. The Lublin paintings were executed in 1418 and are the only scheme that encompasses depictions of the founder. (For a synthetic treatment of the Lublin paintings see [18] (pp. 155–184); for the discussion of the surviving paintings along with the state of earlier research see [19] (pp. 115–121); for the motivations behind Jagiełło’s commissions for Byzantine-style paintings and a summary of earlier scholarship see: [20,21]).

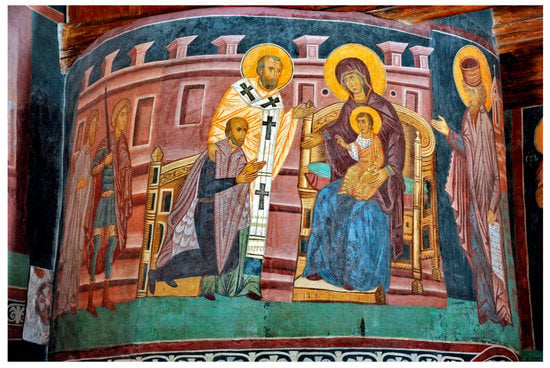

In keeping with the conventions of Byzantine art, the paintings are arranged in descending hierarchical order, and they progress downwards—according to the importance of the subject matter represented—from the vaulting to the walls, running along the nave and chancel walls in horizontal bands. Moreover, the pictures related to the founder are situated in agreement with the Byzantine hierarchical scheme: one of them has been depicted in the western part of the nave (more precisely, in its south-west corner, on the wall of a semi-circular stairway enclosing stairs leading to the choir loft) and on the threshold of the chancel (on the northern jamb of the chancel arch). The painting in the nave represents a foundation scene: Jagiełło shown in adoration of the Virgin and Child, commended to her by St Nicholas and, possibly, St Constantine the Great, whereas inside the chancel arch the king appears in an equestrian portrait (for a detailed analysis of the paintings and an interpretation of their iconographic programme see [22]).

In the foundation scene, Jagiełło was shown according to the Byzantine idiom: on his knees, with raised arms, in prayer to Christ-Emmanuel seated on Mary’s lap. Only Jagiełło’s dress does not conform to the image of a monarch, since he has been shown without any insignia of his royal power, in a grey tunic under a fur-lined cloak (Figure 2). The facial features of the king: an elongated nose, protruding forehead and bald head, represent a physiognomical-type characteristic of the style of the painter responsible for this part of the wall paintings, but when compared with Jagiełło’s likeness carved on his tomb, suggests that it includes also some traits of the king’s actual appearance. St Nicholas, an intercessor for the king, was among the saints universally venerated both in the East and West. According to Anna Różycka-Bryzek, Jagiełło’s devotion for this saint may have originated still at the time when he was living in Lithuania and encountered Orthodox religion daily, in which the cult of this miracle worker and thaumaturge enjoyed enormous popularity. The other saint intercessor for the king, depicted to the right of the Virgin Mary, is in all likelihood Constantine the Great. Although his dress does not fully conform to the model iconography of the saint, the comparisons made of Ladislaus Jagiełło with the first Christian emperor in contemporary political writings and panegyrics fully substantiate this hypothesis (see [22] (pp. 117–121)).

Figure 2.

Ladislaus Jagiełło in adoration of the Virgin and Child, frescoes, 1418, Lublin, royal castle, Holy Trinity Chapel, nave, south-west corner, courtesy of Muzeum Narodowe w Lublinie.

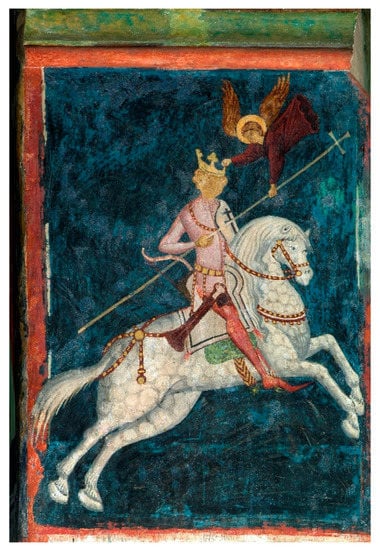

The association of Jagiełło with Constantine the Great has been even more strongly emphasised in the equestrian image painted within the chancel arch. It shows a rider on a white galloping steed, against a blue background, and an angel hovering above, who places a crown on the rider’s head and puts a cross atop a long staff in his hand (Figure 3). Some scholars interpreted this image as a monumental version of the Pogoń coat-of-arms or a depiction of St Ladislaus; the majority, however, have accepted the opinion of Anna Różycka-Bryzek who explained it as Jagiełło’s equestrian portrait, echoing the Byzantine iconographic tradition of the victorious ruler. According to her, the image alludes to depictions of the holy warriors (especially St George and St Theodore), which embody the victorious power of God bestowed upon his earthly representatives. (A discussion about the iconography of this image is extensive and it would be impossible to summarise it here. The most important ones can be found in: [22] (p. 122), [23] (pp. 22–42), [24] (p. 167), [25,26]). However, the analyses conducted some time ago by Tadeusz Trajdos and more recently by Marek Walczak demonstrate that it is not only the Eastern tradition that has informed the iconography of this representation. Equally important was the Western tradition, in which equestrian images of monarchs displayed within the church interior were often related to their successes on the battlefield. The latter scholar interprets the cross being presented to Jagiełło by the angel as an allusion to a spear topped by the sign of Christ’s victory (crux hastata), a motif derived from the story about Constantine’s dream before the battle of the Milvian Bridge, as recounted by Eusebius of Caesarea. The angel who places the pole of the cross in the king’s hand and a crown on his head is a messenger of God—the latter depicted in the chapel on the vault of the chancel as Christ Pantocrator and on the Rood which, in keeping with liturgical practice, would have been mounted on a rood beam running across the chancel arch, that is, directly above the equestrian portrait in question. Thus, the painting emphasises the role of Jagiełło as the second Constantine, and not only his contribution to the dissemination of Christianity but also the preternatural source of his military victories (see [25,27,28]).

Figure 3.

Ladislaus Jagiełło as a rider mounted on a galloping steed, frescoes, 1418, Lublin, royal castle, Holy Trinity Chapel, chancel arch, north jamb, courtesy of Muzeum Narodowe w Lublinie.

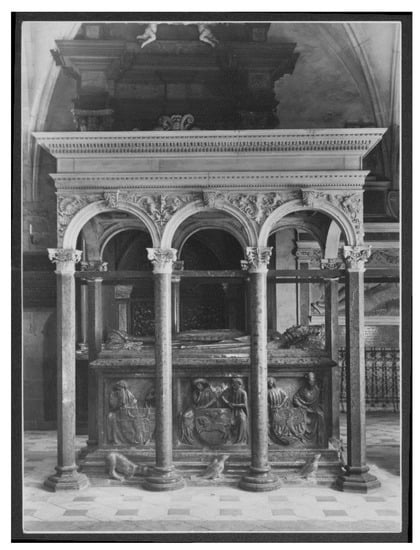

4. The Tomb in Cracow Cathedral on Wawel Hill

The tomb of Ladislaus Jagiełło in Cracow Cathedral on Wawel Hill is chronologically the third royal tomb to have been erected in this church, and—similar to the earlier tombs, of Ladislaus the Short (d. 1333) and Casimir the Great (d. 1370)—has the form of a figurative tomb-chest with a canopy. It is situated in the easternmost arcade between the nave and the south aisle, and originally faced the no longer surviving altar of St Christopher. A recently discovered documentary material attests that it was executed before 1430 and its parts were put together on the designated site probably after the funeral of the king, which took place on 18 June 1434 (on this see [29,30]). The sandstone canopy, executed in 1519–1524 in the workshop of Bartolomeo Berrecci on the commission of Jagiełło’s grandson, Sigismund I the Old, is of a slightly later date. Regrettably, it is not known whether this Renaissance-style canopy replaced an earlier, Gothic one. What is known is that the tomb was intended to have a canopy from the very beginning, as attested by eight columns integrated with the plinth of the tomb-chest (the tomb gave rise to an enormous body of scholarship which cannot be cited here in full and has been limited to the most important publications. For earlier literature, a summary of the state of research, and—sometimes already outdated—discussion of the date, iconography and style of the tomb see [31,32]).

The location of the tomb in the nave, in close proximity to the south doorway, being the cathedral’s main entrance, and not—as was the case of the earlier royal tombs—in the eastern part of the church, separated from the nave by chancel screen, was not accidental. The main advantage of this location was the immediate vicinity of the tomb and shrine of St Stanislaus, a patron saint of the Diocese of Cracow and the entire Polish Kingdom, which stood in medio ecclesiae, in the crossing of the nave and transept. After the victory in the battle of Grunwald, it was precisely at the shrine of St Stanislaus that the banners of the Teutonic Knights seized in the battle by Jagiełło were displayed. Close to the tomb, in the middle of the nave stood also a baptismal font through which Jagiełło entered the Church. Furthermore, the royal tomb almost abutted on the chancel screen topped by the Rood. A location sub crucifixo counted among the most prestigious ones, as it enabled the deceased to remain in perpetual contemplation of the Crucified, before the image representing the triumph of the Saviour over death (on the location of the tomb and related problems see [33] (pp. 153–155), [34] (pp. 73–75)).

The tomb was made of red marble (most likely brought from Hungary), with the top slab bearing an effigy of the king carved in high relief. Jagiełło was shown, in keeping with medieval convention as standing and lying at the same time. His head rests on a cushion supported by a pair of lions and he tramples a symbolical animal in the form of a writhing dragon. His royal dignity is attested by the knightly dress (a long tunic reaching beyond the knees, long shoes and a mantle fastened at the shoulder) and insignia: a sceptre placed along his right arm, an orb supported by his left hand, a sword and an open crown. What is most striking is the countenance of the elderly king: an elongated face with a high forehead, a long, slightly hunched nose and pouted bottom lip. The mimetic quality of this likeness, being an excellent example of a late medieval practice of portraiture which consisted not so much in precise rendering of all details of the king’s actual appearance but rather was based on an image of the king’s face remembered by the artist and reworked in his memory, is additionally strengthened by the motif of closed eyelids, which was relatively rare in North European sepulchral sculpture (on the physiognomy of the king see [35,36], [37] (pp. 215–232)) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Tomb of Władysław Jagiełło, recumbent figure of the king, before 1430, Cracow, cathedral, the easternmost arcade between the nave and the south aisle, photo published in [37].

The decoration of the side walls of the tomb-chest is innovative with regard to the earlier royal tombs in Cracow. They are adorned with shields bearing the arms of the territories of the Polish Kingdom, and on the south side additionally flanked by pairs of mourning supporters, enclosed within square-shaped panels. The following heraldic devices have been represented on the long walls, starting from the head, on the south side: the White Eagle (arms of the land of Cracow and at the same of the entire Polish Kingdom), Pogoń (arms of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania) and arms of the Dobrzyń land; and on the north side: again, the Eagle and Pogoń and the arms of Greater Poland. The shorter wall on the east, under the king’s feet, features the arms of Ruthenia: a lion, and the other one, on the west, under the king’s head, bears the arms of the Wieluń land: an Agnus Dei with the Resurrection banner. The lands represented on the tomb-chest by means of their arms are territories that were either incorporated by Jagiełło into the Polish Kingdom (Grand Duchy of Lithuania) or permanently recovered for Poland through the king’s efforts (Red Ruthenia and the lands of Dobrzyń and Wieluń). The choice and arrangement of the heraldic devices on the tomb-chest alludes to the design of Jagiełło’s Great Seal, but here the set of arms was modified in order not only to display the territorial extent of Jagiełło’s rule as a lord of Poland and Lithuania, but also to emphasise the king’s personal achievement in fulfilling the electoral contract. Nor is it accidental that the short walls bear the arms of the lands of Dobrzyń and Wieluń, which—owing to the signs in their armorial bearings—apart from the political significance, emphasised also the eschatological meaning of the tomb. The first of them, representing a lion, is located in the vicinity of the image of a dragon depicted on the top slab at the king’s feet, and finds substantiation in Psalm 91:13 (“Thou shalt tread upon the lion and adder: the young lion and the dragon shalt thou trample under feet”, KJV). The other device, representing the Agnus Dei, depicted at the head of the tomb-chest, refers to the king, as a promise of his salvation and resurrection (for a recently conducted in-depth analysis of the programme of the side walls of the tomb-chest see [16]) (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Tomb Ladislaus Jagiełło, before 1430, Cracow, cathedral, the easternmost arcade between the nave and the south aisle, photo published in [37].

As supposed by Marek Janicki, the theme of expanding the possessions of the Kingdom and of the recovery of its territories may have been related to the king’s efforts, started in the 1420s, to secure the succession of his male descendants. The political message of this programme is supplemented by figures supporting the shields and mourning the king’s death. These men—of various status and age—neither represent (as had been suggested in earlier scholarship) members of the king’s council nor personify various social strata or generations, nor do they portray actual historical figures. Rather, they are representatives of particular lands of the Kingdom and at the same time, are the most important dignitaries in the state (including two clergymen: the archbishop of Gniezno and the bishop of Cracow) who secured the observation of law and political order in the Kingdom during the interregnum. Their sadness is an expression of a grief of the subjects orphaned by their deceased king (intentionally shown on the top slab with closed eyelids), illustrating the state of the monarchy bereaved of its most important person. Thus, the entire figurative and heraldic programme of the tomb can be understood as a eulogy to Ladislaus Jagiełło, consisting of demonstrating his achievement as a result of his unwavering fulfilment of the electoral contract and the oath taken before his coronation in Cracow (see again [16] (pp. 142–149) and [37] (pp. 223–232)).

The figurative and heraldic programme of the tomb is supplemented by representations of animals, shown as if strolling along the plinth. Figures of dogs alternate with those of falcons, facing the head of the tomb-chest. Their presence on the plinth must be related to Jagiełło’s love of hunting and falconry; well attested in documentary evidence, yet their unequivocal interpretation is rather difficult. In earlier scholarship, they were understood as conveying eschatological, theological and astrological and even mythological meaning. It is more likely, however, that they are part of the overall concept of mourning the deceased king presented on the side walls of the tomb-chest (the dogs clinging with their forepaws to the ground should be understood as expressing subjection, or perhaps, fear, rather than attacking, as had been suggested earlier). (For the figures of animals, along with a summary of earlier hypotheses, see [16] (pp. 156–158)).

It is worthy to note that the tomb of Ladislaus Jagiełło is striking not only by its innovative iconography but also its novel forms. The realistic rendering of some of its elements (including the king’s facial features on the top slab, with closed eyes, and the images of animals on the plinth) as well as its stylistic features, which practically have no analogies in Central European sculpture of the period, have induced some scholars into interpreting the tomb as a work of proto-Renaissance or even Renaissance art, allegedly carved by artists familiar with the art of the Florentine Quattrocento. (Such an opinion had prevailed for a long time, having been introduced by Karol Estreicher in his study of the tomb [38] (pp. 12–13)). The most controversial theory, claiming that the tomb was supposedly executed by Donatello, put forward by Anna Boczkowska [39], was unanimously rejected by all scholars dealing with the tomb; see the reviews of her book [40,41,42]. In fact, the sculptures on the tomb stylistically correspond to International Gothic, in which the idealised convention of representation harmoniously coexists with realistically rendered details in the figures of men, fauna and flora. The most recent research assumes that the tomb may have been executed by artists from northern Italy (the Veneto and Lombardy) (see [35] (pp. 123–128), [36] (pp. 61–70)), and the output of Aegidius Gutenstein from Wiener Neustadt, active in Padua in 1422–1438, has been postulated as an important point of reference for the Cracow monument [43] (pp. 488–489).

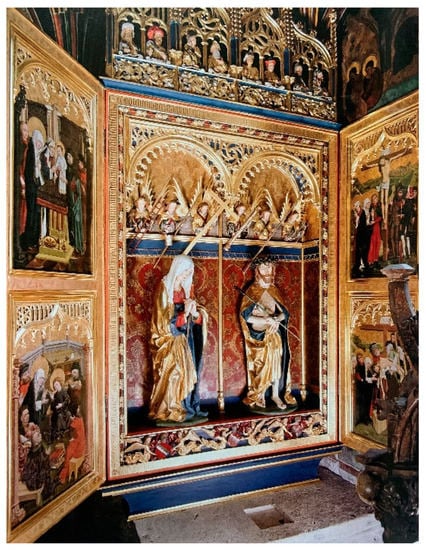

5. A Panel with the Adoration of the Magi

A scene representing the Adoration of the Magi, in which one of the Magi visiting the Christ Child in Bethlehem was given the facial features of Ladislaus Jagiełło, is depicted on the reverse of the right wing in a triptych in the Chapel of the Holy Cross in Cracow Cathedral, located on an altar table facing the tomb of Casimir IV Jagiellonian, Jagiełło’s youngest son and his heir on the Polish throne. The carved and painted wooden altarpiece was most probably executed around 1475, during the furnishing of the then newly built tomb chapel. Although there is no documentary evidence that would confirm a relationship between the altarpiece and the ruling house, the destination of the triptych to a place that from the very beginning had been intended as a royal tomb chapel and the presence of shields with the arms of the Habsburgs, the Polish Kingdom and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania on the bottom part of the triptych’s wooden shrine, suggest that the altarpiece was likely commissioned by Casimir and his consort Elizabeth of Austria.

The iconography of the retable, with the figures of the Man of Sorrows and the Sorrowful Virgin accompanied by angels holding the Instruments of the Passion in the shrine, corresponds to the function of an altarpiece in a tomb chapel, where masses were celebrated alteram pro peccatis, alteram pro defunctis (in the sepulchral context of the chapel both figures embodied mercy, misericordia, that is, an attribute of Christ that would save the sinners at the Last Judgement) (Figure 6). At the same time, the iconography of the retable alluded to the Passion relics: pieces of the True Cross, the Holy Nails and the Crown of Thorns kept in the chapel. (On the iconography of the altarpiece and the date and circumstances of its execution see [44] (pp. 210-221). On the former decoration and furnishings of the chapel which housed the retable, see [45]).

Figure 6.

Triptych, wood and polychromy, ca. 1475, Cracow, cathedral, Chapel of the Holy Cross, photo published in [44].

The panel representing the Adoration of the Magi, along with other painted scenes on the triptych’s wings, was executed by a master trained in the local school of painting but with first-hand knowledge of Netherlandish art. The panel shows the Virgin Mary presenting the Christ Child to the oldest of the Magi, who, kneeling, kisses the hand of the Saviour. The other kings are shown standing on either side of the Virgin and seem to be getting ready to lay down the frankincense and myrrh at her feet. The image of the king on the left, who lifts up the crown with his hand, revealing his bald head, may be considered Jagiełło’s identification portrait because of its close resemblance to his figure carved on his tomb (Figure 7). (For the altarpiece’s painted panels and a summary of the state of research see [19] (pp. 195–197). For the identification portrait as a specific type of portraiture, see, especially with regard to the Middle Ages, e.g. [46,47]). At the time when the panel in question originated, the tradition of identifying monarchs in art with one of the Three Magi had been already well established. In France, where images of this kind were the earliest to appear, they were associated with the imitatio pietatis, inextricably connected to the piety of the monarch, who expressed his reverence to the Incarnated God by imitating the Three Magi. In the Holy Roman Empire, after the relics of the Three Magi had been removed from Milan to Cologne, a custom was established of the kings of the Romans making a pilgrimage to the shrine of the Three Magi in Cologne immediately after coronation, held in the nearby Aachen. Charles IV of Luxembourg and Sigismund of Luxembourg have been portrayed as the Magi paying homage to the Christ Child several times, demonstrating in this way not only their attachment to the relics held in Cologne, but also a sacred dimension of their imperial power. Furthermore, numerous rulers of the Habsburg dynasty have been portrayed in this manner. In the case of Ladislaus Jagiełło, it was his status as a neophyte that had played the key role in the decision to portray him in this way, as it was a unique quality that likened the Polish–Lithuanian monarch to the legendary Three Magi. The panel depicting Jagiełło under the guise of the youngest of the Three Magi is a reminder about his personal contribution to the spreading of Christianity and demonstrated the piety of the monarch who—although born as a pagan—paid homage to the Incarnated God and recognised his sovereignty over the world [48] (p. 22), [49] (pp. 127–130). Because the style of the paintings in the triptych’s wings is clearly influenced by Flemish art, it has been assumed that their maker may have been inspired by works of Netherlandish art, such as an altarpiece from the church of St Columba in Cologne, with an identification portrait of the Duke of Burgundy, Charles the Bold (see [50] (p. 154), [51] (pp. 368–369)).

Figure 7.

Adoration of the Magi, wing panel of a triptych, tempera on wood, ca. 1475, Cracow, cathedral, Chapel of the Holy Cross, photo published in [37].

6. Conclusions

The medieval iconography of Ladislaus Jagiełło, modest as it is, with only a few surviving portraits, stands out by its innovative use of pictorial formulas and heraldic devices, as well as by consistently propagating the image of the king as a pious neophyte ruler and victorious commander; a monarch who duly fulfilled the commitments of his electoral contract and the oath taken before he was crowned king of Poland.

In the diplomatic sphere, the majesty of the king was conveyed by his image represented on the Great Seal, which came into use shortly after Jagiełło’s coronation and had remained in service throughout his entire reign. This seal represents a novel type in Polish sigillography, conveying the idea of Jagiełło’s contractual-elective rule as a successor to the Piasts on the Polish throne and simultaneously a lord of Lithuania, through an image of the enthroned monarch surrounded by a group of heraldic emblems of the state and its lands.

The remaining likenesses of the king, made on his initiative, had a commemorative function: two portraits painted in the Holy Trinity Chapel at the royal castle of Lublin in 1418, and his effigy in the tomb executed before 1430 and after Jagiełło’s death assembled in Cracow Cathedral—a church serving as a burial site of Polish monarchs since the reign of the last Piast kings.

The wall paintings in Lublin, being one of several such schemes of fresco paintings commissioned by the king and executed in keeping with the precepts of Byzantine monumental painting by artists brought from Ruthenia, include a founder’s portrait of Jagiełło, which shows him in adoration of the Virgin Mary and Child, and his equestrian portrait, which praises his contributions in the military and ecclesiastical fields by means of likening him to the Emperor Constantine the Great.

Jagiełło’s monument of red marble, in the form of a tomb-chest with figural decoration and an architectural canopy, alludes to the forms of two earlier royal tombs located in the chancel of Cracow Cathedral, but its iconographic programme is entirely original and was dictated by a desire to demonstrate the king’s involvement in securing the territorial integrity of the Polish Kingdom. Jagiełło, shown in effigy on the top slab, with closed eyes, is accompanied on the side walls of the tomb-chest by mourning figures holding shields with armorial devices of the state and its lands—representatives of regional communities of the Kingdom, who guaranteed the political and constitutional order during the interregnum. Their sadness expresses the grief of the subjects orphaned by their king and shows the condition of the monarchy bereaved of the most important person in the state. The choice and arrangement of heraldic devices on the tomb-chest is undoubtedly an allusion to the design of Jagiełło’s Great Seal, with a modification in the choice of the coats-of-arms intended to manifest the king’s personal contribution in his carrying out of the electoral contract.

The last of the portraits discussed here attests to keeping Jagiełło’s memory alive by Casimir IV Jagiellonian, his son and successor on the Polish throne. The portrayal of the founder of the Jagiellonian dynasty as one of the Three Magi offering gifts to the Christ Child in Bethlehem, depicted on the reverse of a triptych wing mounted on an altar table in the Holy Cross Chapel opposite to Casimir’s tomb, reminded his descendants about the merits of the neophyte king for Christianity and attested to the piety of the monarch who, although born as a pagan, paid homage to Incarnated God and recognised his sovereignty over the world.

Funding

This research was funded by The Ministry of Science and Higher Education of Poland, grant number NPRH nr 0467/NPRH5/H30/84/2017 (Iconography of Jagiellonians as kings of Poland and grand dukes of Lithuania and members of their Families 1386–1795).

Acknowledgments

I thank Joanna Wolańska for translating this entry into English.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Entry Link on the Encyclopedia Platform

References

- Tęgowski, J. Pierwsze pokolenia Giedyminowiczów (The First Generations of the Gediminids); Wydawnictwo Historyczne: Poznań, Poland; Wrocław, Poland, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Akta unji Polski z Litwą 1385–1791 (Records of the Union of Poland and Lithuania); Kutrzeba, S.; Semkowicz, W. (Eds.) Polska Akademia Umiejętności: Cracow, Poland, 1932; no. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Krzyżaniakowa, J.; Ochmański, J. Władysław Jagiełło (Ladislaus Jagiełło), 2nd ed.; Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich: Wrocław, Poland; Cracow, Poland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Błaszczyk, G. Dzieje Stosunków Polsko-Litewskich (History of the Polish-Lithuanian Relations). Volume 2: Od Krewa do Lu-Blina (From Krevo to Lublin); Wydawnictwo Poznańskie: Poznanń, Poland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Wyrozumski, J. Królowa Jadwiga. Między Epoką Piastowską a Jagiellońską (Queen Hedwig. between the Epochs of the Piasts and the Jagiellonians), 2nd ed.; Universitas: Cracow, Poland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Joannis Dlugossii Annales seu Cronicae Incliti Regni Poloniae, lib. XI et lib. XII: 1431–1444, Consilium ed; Wyrozumski, G., Ed.; Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN: Varsaviae, Poland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Krzyżaniakowa, J.; Ochmański, J. Władysław Jagiełło w Opiniach Swoich Współczesnych (Ladislaus Jagiełło in the Opinions of his Contemporaries); Wydawnictwo Naukowe Uniwersytetu Adama Mickiewicza w Poznaniu: Poznań, Poland, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Kultura Wielkiego Księstwa Litewskiego. Analizy i Obrazy (The Culture of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. Analyses and Images); Ališauskas, V.; Jovaiša, L.; Paknys, M.; Petrauskas, R.; Raila, E. (Eds.) Universitas: Cracow, Poland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Szajnocha, K. Jadwiga i Jagiełło. 1374–1413 (Hedwig and Jagiełło. 1374–1413); Drukarnia, A.T., Ed.; Jezierskiego: Warsaw, Poland, 1855–1856; Volume 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Kuczyński, S.M. Król Jagiełło (King Jagiełło); Wydawnictwo Ministerstwa Obrony Narodowej: Warsaw, Poland, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Borkowska, U. Dynastia Jagiellonów w Polsce (The Jagiellonian Dynasty in Poland); Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN: Warsaw, Poland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sułkowska-Kurasiowa, I. Dokumenty Królewskie i ich Funkcja w Państwie Polskim za Andegawenów i Pierwszych Jagiellonów 1370–1444 (Royal Documents and their Use in the Kingdom of Poland during the Reign of the Angevins and the first Jagiellonians 1370–1444); Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe: Warsaw, Poland, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Gumowski, M. Pieczęcie Królów Polskich (Seals of Polish Kings); Towarzystwo Numizmatyczne: Cracow, Poland, 1910. [Google Scholar]

- Kuczyński, S.K. Polskie Herby Ziemskie. Geneza, Treści, Funkcje (Polish Provincial Coats of Arms. Origins, Meanings, Functions); Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN: Warsaw, Poland, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Piech, Z. Monety, Pieczęcie i Herby w Systemie Władzy Jagiellonów (Coins, Seals and Coats of Arms in the System of Jagiellonian Symbols of Power); DiG: Warsaw, Poland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Janicki, M. Polityczny program ideowy tumby Władysława Jagiełły a czas jej powstania (The Political programme on the tomb-chest of Władysław Jagiełło and the date of its execution). Średniowiecze Polskie i Powszechne 2015, 7, 95–159. [Google Scholar]

- Turska, K. Ubiór Dworski w Polsce w Dobie Pierwszych Jagiellonów (Courtly Costume in Poland in the Time of the First Jagiellonians); Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich: Wrocław, Poland; Warsaw, Poland; Cracow, Poland; Łódź, Poland, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Różycka-Bryzek, A. Malowidła Ścienne Bizantyńsko-Ruskie (Byzantine-Ruthenian Mural Paintings). In Malarstwo Gotyckie w Polsce (Gothic Painting in Poland) (Volume 1: Synteza (Synthesis)); Labuda, A.S., Secomska, K., Eds.; DiG: Warsaw, Poland, 2004; pp. 155–184. [Google Scholar]

- Malarstwo gotyckie w Polsce (Gothic Painting in Poland), Volume 2: Katalog zabytków (Catalogue); Labuda, A.S.; Secomska, K. (Eds.) DiG: Warsaw, Poland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Jurkowlaniec, G. The Artistic Patronage of Ladislaus Jagiełło. Beyond the Opposition between East and West. In Bizancjum a Renesansy. Dialog Kultur, Dziedzictwo Antyku, Tradycja i Współczesność/Byzantium and Renaissances. Dialogue of Cultures, Heritage of Antiquity, Tradition and Modernity; Janocha, M., Sulikowska, A., Tatarova, I., Flisowska, Z., Mroziewicz, K., Smólska, N., Smólski, K., Eds.; Wydawnictwo Campidoglio: Instytut Badań Interdyscyplinarnych “Artes Liberales” UW: Warsaw, Poland, 2012; pp. 271–281. [Google Scholar]

- Kruk, M.P. Malowidła Graeco Opere fundacji Jagiellonów jako postulat unii państwowej i kościelnej oraz jedności Kościoła (The ”Greek-Style” Paintings Commissioned by Rulers from the Jagiellonian Dynasty as an Argument Supporting the State and Church Union and Church Unity). In Między Teologią a Duszpasterstwem Powszechnym na Ziemiach Korony Doby Przedtrydenckiej. Dziedzictwo Średniowiecza i Wyzwania XV–XVI Wieku; Walecki, W., Ed.; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego: Warsaw, Poland, 2017; pp. 145–201. [Google Scholar]

- Różycka-Bryzek, A. Bizantyńsko-Ruskie Malowidła w Kaplicy Zamku Lubelskiego (Byzantine-Ruthenian Mural Paintings in the Lublin Castle Chapel); Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe: Warsaw, Poland, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Walicki, M. Malowidła ścienne kościoła św. Trójcy na zamku w Lublinie (1418) (Mural Paintings of the Holy Trinity Church at the Lublin Castle). Studia do Dziejów Sztuki w Polsce 1930, 3, 1–92. [Google Scholar]

- Śnieżyńska-Stolot, E. Sigismund and His Times in the Art 1387–1437. In Cultural Institutions in the 19th Century as an Example of National Revival in Poland, Bohemia, Slovakia and Hungary; Hyży, E., Wójcik, A., Eds.; Stowarzyszenie Historyków Sztuki: Cracow, Poland, 1991; pp. 163–169, (Seminaria Niedzickie, 5). [Google Scholar]

- Trajdos, T. Treści ideowe wizerunków Jagiełły w kaplicy zamku lubelskiego (The Meaning of Jagiełło’s Portraits in the Chapel at the Lublin Castle). Biuletyn Historii Sztuki 1979, 41, 316–320. [Google Scholar]

- Różycka-Bryzek, A. Uwagi o referacie T.M. Trajdosa pt. Treści ideowe wizerunków Jagiełły w kaplicy zamku lubelskiego (Comments on the Paper by T.M. Trajdos “The Meaning of Jagiełło’s Portraits in the Chapel at the Lublin Castle”). Biuletyn Historii Sztuki 1980, 42, 437–443. [Google Scholar]

- Walczak, M. Portret konny króla Władysława Jagiełły w kaplicy Trójcy Świętej na zamku w Lublinie (The Equestrian Portrait of King Ladislaus Jagiełło in the Holy Trinity Chapel at the Castle of Lublin). In Patronat Artystyczny Jagiellonów (Artistic Patronage of the Jagiellonians); Walczak, M., Węcowski, P., Eds.; Societas Vistulana: Cracow, Poland, 2015; pp. 305–320. [Google Scholar]

- Walczak, M. “Sic enim Constantinus…” The Equestrian Portrait of King Ladislaus Jagiełło in the Holy Trinity Chapel at the Castle of Lublin (1418). In Eclecticism in Late Medieval Visual Culture at the Crossroads of the Latin, Greek, and Slavic Traditions; Rossi, M.A., Sullivan, A.I., Eds.; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany; Boston, MA, USA, 2022; pp. 259–289. [Google Scholar]

- Włodarek, A. Przyczynek do datowania nagrobka Władysława Jagiełły w katedrze wawelskiej (A Contribution to the Dating of the Tomb of Ladislaus Jagiełło in Cracow Cathedral on Wawel Hill). Biuletyn Historii Sztuki 2012, 74, 443–481. [Google Scholar]

- Janicki, M. Problem datowania nagrobka Władysława Jagiełły w świetle źródeł i dotychczasowej literatury (A Problem of the Dating of the Tomb of Ladislaus Jagiełło in the Light of the Sources and Existing Literature). In Patronat Artystyczny Jagiellonów (Artistic Patronage of the Jagiellonians); Walczak, M., Węcowski, P., Eds.; Societas Vistualana: Cracow, Poland, 2015; pp. 321–358. [Google Scholar]

- Mrozowski, P. Polskie Nagrobki Gotyckie (Polish Gothic Tombs); Zamek Królewski w Warszawie: Warsaw, Poland, 1994; pp. 82–88. [Google Scholar]

- Chrubasik, K. Das Grabmal von Ladislaus II. Jagiełło (1386–1434). Inszenierung und Legitimation der Macht. Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Philosophischen Fakultät der Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität zu Bonn. 2009. Available online: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:hbz:5-17567 (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- Walczak, M. Topografia nekropolii królewskiej na Wawelu w średniowieczu (Topography of the Royal Necropolis at Wawel in the Middle Ages). In Procesy Przemian w Sztuce Średniowiecznej. Przełom—Regres—Innowacja—Tradycja (Processes of Change in the Art of the Middles Ages. Breakthrough—Decline—Innovation—Tradition); Eysymontt, R., Kaczmarek, R., Eds.; Stowarzyszenie Historyków Sztuki: Warsaw, Poland, 2014; pp. 147–161. [Google Scholar]

- Walczak, M. Topography of the Royal Necropolis at the Cracow Cathedral in the Middle Ages. In Epigraphica et Sepulcralia. Fórum Epigrafických a Sepulkrálních Studií; Roháček, J., Ed.; Artefactum: Prague, Czech Republic, 2015; Volume 6, pp. 67–90. [Google Scholar]

- Grzęda, M. The Birth of Portraiture in Poland? The Face of King Ladislas II Jagiello on his Tomb in Cracow. In Art and Architecture around 1400. Global and Regional Perspectives; Ciglenečki, M., Vidmar, P., Eds.; Faculty of Arts of the University of Maribor: Maribor, Slovenia, 2012; pp. 121–139. [Google Scholar]

- Grzęda, M. Wizerunek Władysława Jagiełły na nagrobku w katedrze na Wawelu (The Likeness of Ladislaus Jagiełło on his Tomb in Cracow Cathedral). Folia Hist. Artium Ser. Nowa 2015, 13, 51–72. [Google Scholar]

- Grzęda, M. Między Normą a Naturą. Początki Portretu w Europie Środkowej (ok. 1350–1430) (Between Norm and Nature. The Origins of Portraiture in Central Europe (ca. 1350–1430)); Societas Vistulana: Cracow, Poland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Estreicher, K. Grobowiec Władysława Jagiełły (The Tomb of Ladislaus Jagiełło). Rocz. Krak. 1953, 33, 1–43. [Google Scholar]

- Boczkowska, A. Sarkofag Władysława II Jagiełły i Donatello. Początki odrodzenia w Krakowie. Sztuka—Polityka—Humanizm (The Tomb of Ladislaus Jagiełło and Donatello. The Origins of the Renaissance in Cracow. Art—Politics—Humanism); Nowe Terytoria: Gdańsk, Poland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Walczak, M. Nagrobek Władysława Jagiełły, Donatello i metodologia historii sztuki: Uwagi na marginesie ksiąŊki Anny Boczkowskiej Sarkofag Władysława II Jagiełły i Donatello. Początki odrodzenia w Krakowie. Sztuka—Polityka—Humanizm (The Tomb of King Ladislaus Jagiełło, Donatello and the Methodology of Art History: Some Observations on the Monograph of Anna Boczkowska “The Tomb of Ladislaus Jagiełło and Donatello: The Origins of the Renaissance in Cracow: Art—Politics—Humanism”). Studia Źródłoznawcze 2012, 50, 130–137. [Google Scholar]

- Płonka-Bałus, K. O trudnej „sztuce widzenia” i czytaniu źródeł: Dwie publikacje o nagrobku króla Władysława Jagiełły w katedrze krakowskiej (On the difficult “art of seeing” and reading the sources. Two publications on the tomb of King Władysław Jagiełło in Cracow Cathedral). Modus 2013, 12–13, 147–159. [Google Scholar]

- Fabiański, M. [rec.] “Sarkofag Władysława II Jagiełły i Donatello: Początki odrodzenia w Krakowie; sztuka, polityka, humanizm” ([rev.] The Tomb of Ladislaus Jagiełło and Donatello: The Origins of the Renaissance in Cracow: Art—Politics—Humanism, Anna Boczkowska, Gdańsk 2011). Biuletyn Historii Sztuki 2012, 74, 743–746. [Google Scholar]

- Horzela, D.; Walczak, M. Fundacje artystyczne elit duchownych i świeckich w Małopolsce wobec czeskiego stylu pięknego około 1400 roku (The Artistic Patronage of Ecclesiastical and Lay Elites in Lesser Poland in Relation to Bohemia’s Beautiful Style around 1400). In Kościół w Społeczeństwie w Czechach i w Polsce: W Średniowieczu i w Epoce Nowożytnej (The Church in Czech and Polish Societies in the Middle Ages and the Early Modern Period); Iwańczak, W., Ed.; Akademia Ignatianum w Krakowie: Cracow, Poland, 2020; pp. 488–489. [Google Scholar]

- Horzela, D. Późnogotycka rzeźba drewniana w Małopolsce ok. 1440–1477 (Late Gothic wood sculpture in Lesser Poland ca. 1440-1477); Societas Vistulana: Cracow, Poland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Walczak, M. Liturgical furnishings of the Holy Cross Chapel in the cathedral on Wawel Hill. Contribution to the studies into the piety of the Jagiellonians. In Epigraphica et Sepulcralia. Fórum Epigrafických a Sepulkrálních Studií; Artefactum: Prague, Czech Republic, 2016; Volume 7, pp. 35–57. [Google Scholar]

- Polleross, F.B. Das Sakrale Identifikationsporträt. Ein Höfischer Bildtypus von 13. bis zum 20. Jahrhundert; Wernersche Verlagsgesellschaft: Stuttgart, Germany, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, G. Beiträge zum gotischen Kryptoporträt in Frankreich. In Malerei der Gotik. Fixpunkte und Ausblicke, Volume 2: Malerei der Gotik in Sud- und Westeuropa. Studien zum Herrscherporträt; Roland, M., Ed.; Akademische Druck- u. Verlagsanstalt: Graz, Austria, 2005; pp. 329–330. [Google Scholar]

- Mrozowski, P. Wizerunek królewski w systemie reprezentacji władzy w Polsce jagiellońskiej (The Royal Image in the System of Representation of Power in Poland under the Jagiellonians). In Patronat Artystyczny Jagiellonów (Artistic Patronage of the Jagiellonians); Walczak, M., Węcowski, P., Eds.; Societas Vistulana: Cracow, Poland, 2015; pp. 17–41. [Google Scholar]

- Grzęda, M. Portret i figuralna interpretacja historii: Portret identyfikacyjny w reprezentacji władzy Jagiellonów (Portraiture and Figural Interpretation of History: Identification Portraits in the Representation of Power of the Jagiellonians). Gdańskie Studia Muzealne Seria Nova 2019, 11, 122–141. [Google Scholar]

- Gadomski, J. Gotyckie Malarstwo Tablicowe Małopolski 1460–1500 (Gothic Panel Painting of Lesser Poland 1460–1500); Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe: Warsaw, Poland, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Łanuszka, M. Tryptyk Matki Boskiej Bolesnej w kaplicy Świętokrzyskiej—Najbardziej niderlandyzujące dzieło z fundacji Jagiellonów (The Triptych of Our Lady of Sorrows in the Holy Cross Chapel—A Work Revealing the Most Distinct Influences of Netherlandish Art among those Commissioned by the Rulers from the Jagiellonian Dynasty). In Patronat artystyczny Jagiellonów (Artistic Patronage of the Jagiellonians); Walczak, M., Węcowski, P., Eds.; Societas Vistulana: Cracow, Poland, 2015; pp. 359–372. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).