Annotated Barriers to Peritoneal and Home Hemodialysis in the U.S.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Governmental Authoritarianism Through Guidelines

3. Administrative Authoritarianism

- A.

- The choice of antibiotics for exit-site topical prophylactic care, empiric exit-site infection treatment, and empiric peritonitis treatment are medical decisions only. Yet facility administrators weigh in based on expense and availability. Obviously, these are negotiable, but often the medical directors acquiesce to the financial/administrative argument at the expense of medical justification.

- B.

- Icodextrin has a slight cost differential to standard dextrose PD solutions. Once, a Large Dialysis Organization administrator told a PD-savvy nephrologist friend that, if she knew more about how PD works, she would not need to prescribe icodextrin. There are certain patients that benefit from more than one icodextrin exchange per day [15,16,17,18]. Despite being off FDA labeling, this practice is safe and effective and can prolong PD technique survival for many months.

- C.

- Similarly, the use of a certain type of cycler may advantage one clinical situation over another, but, for contracts (read that as expenses), only a certain type of cycler is offered in that clinic. This is relevant for several clinical reasons such as the ability for remote monitoring of the treatment and for addressing drainage issues. Again, medical decisions and opportunities can be and are jeopardized by local administrative decisions.

- D.

- There are patients who would greatly benefit from the hybridization of hemodialysis with PD [19,20,21,22]. This most often occurs while electively transitioning from one to the other, but, in Japan, for example, this is not an infrequently occurring practice. Administrative prohibitions may dominate.

- E.

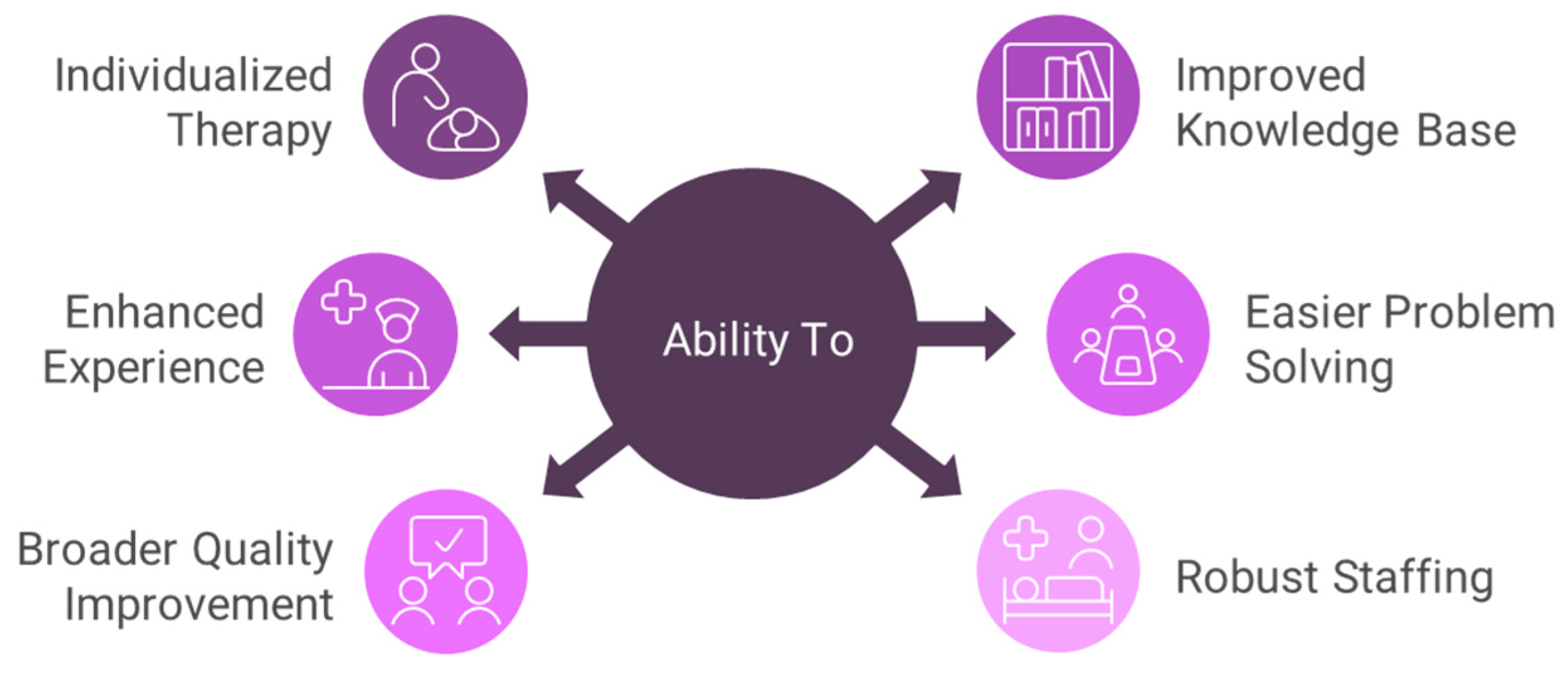

- Staffing is a component of the quality of care. Some administrators defer to a standard staffing ratio of patients per nurse (social worker, dietician) regardless of the setting. By setting, I refer to location (e.g., urban, dense urban, suburban, rural, distant rural), access to the Internet, experience of the staff, back-up facilities and their proximity, number of clinicians referring and their experience, the expertise of the medical director, and the off-site support from the dialysis organization. What I term “the Godzilla Effect” is that size does matter for many of these settings. It is well described that outcomes are vastly superior in larger PD programs [23,24,25]. The advantages of a larger program are described in Figure 1.

4. Frequency-Related Barriers

5. Special Space and Service Designations

6. Solutions and Opportunities

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Golper, T.A.; Saxena, A.B.; Piraino, B.; Teitelbaum, I.; Burkart, J.; Finkelstein, F.; Abu-alfa, A. Systematic Barriers to The Effective Delivery of Home Dialysis in The, U.S. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2011, 58, 879–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, B.A.; Chan, C.; Blagg, C.; Lockridge, R.; Golper, T.; Finkelstein, F.; Shaffer, R.; Mehrotra, R. How to overcome barriers and establish a successful home HD program. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2012, 7, 2023–2032. [Google Scholar]

- Flanagin, E.P.; Chivate, Y.; Weiner, D.E. Home Dialysis in the United States: A Roadmap for Increasing Peritoneal Dialysis Utilization. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2020, 75, 413–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Advancing American Kidney health, Executive Order 13879. Federal Register. 10 July 2019; Volume 84, pp. 33817–33819. Available online: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/DCPD-201900464/pdf/DCPD-201900464.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- Golper, T.; Churchill, D.; Burkart, J.; Firanek, C.; Geary, D.; Gotch, F.; Moore, L.; Nolph, K.; Powe, N.; Singh, H.; et al. NKF-DOQI Clinical Practice Guidelines for Peritoneal Dialysis Adequacy. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 1997, 30 (Suppl. 3), S67–S108. [Google Scholar]

- Navaratnarajah, A.; Clemenger, M.; McGrory, J.; Hisole, N.; Chelapurath, T.; Corbett, R.W.; Brown, E.A. Flexibility in peritoneal dialysis prescription: Impact on technique survival. Perit. Dial. Int. 2021, 41, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, E.A.; Blake, P.G.; Boudville, N.; Davies, S.; de Arteaga, J.; Dong, J.; Finkelstein, F.; Foo, M.; Hurst, H.; Johnson, D.W.; et al. International Society for Peritoneal Dialysis practice recommendations: Prescribing high-quality goal-directed peritoneal dialysis. Perit. Dial. Int. 2020, 40, 244–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teitelbaum, I.; Glickman, J.; Neu, A.; Neumann, J.; Rivara, M.B.; Shen, J.; Wallace, E.; Watnick, S.; Mehrotra, R. KDOQI US Commentary on the 2020 ISPD Practice Recommendations for Prescribing High-Quality Goal-Directed Peritoneal Dialysis. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2020, 77, 157–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maliha, G.; Weinhandl, E.D.; Reddy, Y.N.V. Deprescribing the Kt/V Target for Peritoneal Dialysis in the United States: The Path Toward Adopting International Standards for Dialysis Adequacy. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2023, 34, 751–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nissenson, A.; Chertow, G.; Conway, P. Breaking the Barriers to Innovation in Kidney Care. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2022, 17, 591–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watnick, S.; Blake, P.G.; Mehrotra, R.; Mendu, M.; Roberts, G.; Tummalapalli, S.L.; Weiner, D.E.; Butler, C.R. System-Level Strategies to Improve Home Dialysis: Policy Levers and Quality Initiatives. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2023, 18, 1616–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Bargman, J.M. PET Testing has Utility in the Prescription of Peritoneal Dialysis: CON. Kidney360 2024, 5, 1794–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Hare, A.M.; Rodriguez, R.A.; Barrett Bowling, C.B. Caring for patients with kidney disease: Shifting the paradigm from evidence-based medicine to patient-centered care. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2016, 31, 368–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manera, K.E.; Johnson, D.W.; Craig, J.C.; Shen, J.I.; Ruiz, L.; Wang, A.Y.-M.; Yip, T.; Fung, S.K.S.; Tong, M.; Lee, A.; et al. Patient and Caregiver Priorities for Outcomes in Peritoneal Dialysis: Multinational Nominal Group Technique Study. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2019, 14, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gobin, J.; Frenando, S.; Santacroce, S.; Finkelstein, F.O. The utility of two daytime icodextrin exchanges to reduce dextrose exposure in automated peritoneal dialysis patients: A pilot study of nine patients. Blood Purif. 2008, 26, 279–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sav, T.; Oymak, O.; Inanc, M.T.; Dogan, A.; Tokgoz, B.; Utas, C. Effects of twice-daily icodextrin administration on blood pressure and left ventricular mass in patients on continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. Perit. Dial. Int. 2009, 29, 443–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballout, A.; Garcia-Lopez, E.; Struyven, J.; Marechal, C.; Eric Goffin, E. Double-dose icodextrin to increase ultrafiltration in PD patients with inadequate ultrafiltration. Perit. Dial. Int. 2011, 31, 91–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dousdampanis, P.; Trigka, K.; Chu, M.; Kahn, S.; Venturoli, D.; Oreopoulos, D.G.; Bargman, J.M. Two icodextrin exchanges per day in peritoneal dialysis patients with ultrafiltration failure: One center’s experience and review of the literature. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2011, 43, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sriperumbuduri, S.; Biyani, M.; Brown, P.; McCormick, B.B. Retrospective study of patients on hybrid dialysis: Single-center data from North America. Perit. Dial. Int. 2020, 40, 224–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeda, M.; Nonaka, H.; Nangaku, M.; Mise, N. Health-related quality of life on combination therapy with peritoneal dialysis and hemodialysis in comparison with hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis: A cross-sectional study. Perit. Dial. Int. 2020, 40, 462–469. [Google Scholar]

- Masakane, I.; Nakai, S.; Ogata, S.; Kimata, N.; Hanafusa, N.; Hamano, T.; Wakai, K.; Wada, A.; Nitta, K. Annual dialysis data report 2014, JSDT renal data registry (JRDR). Ren. Replace. Ther. 2017, 3, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukui, H.; Hara, S.; Hashimoto, Y.; Horiuchi, T.; Ikezoe, M.; Itami, N.; Kawabe, M.; Kawanishi, H.; Kimura, Y.; Nakamoto, H.; et al. Review of combination of peritoneal dialysis and hemodialysis as a modality of treatment for end-stage renal disease. Ther. Apher. Dial. 2004, 8, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schaubel, D.E.; Blake, P.G.; Fenton, S.S.A. Effect of renal center characteristics on mortality and technique failure on peritoneal dialysis. Kidney Int. 2001, 60, 1517–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huisman, R.M.; Martin, G.M.; Nieuwenhuizen, M.G.M.; de Charro, F.T. Patient-related and centre-related factors influencing technique survival of peritoneal dialysis in The Netherlands. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2002, 17, 1655–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrotra, R.; Khawa, O.; Duong, U.; Fried, L.; Norris, K.; Nissenson, A.; Kalantar-Zadeh, K. Ownership patterns of dialysis units and peritoneal dialysis in the United States: Utilization and outcomes. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2009, 54, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018. Available online: https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/house-bill/1892/text (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- Sloand, J.A.; Marshall, M.R.; Barnard, S.; Pendergraft, R.; Rowland, N.; Lindo, S.J. Peritoneal dialysis (PD) patient and nurse preferences around novel and standard automated PD device features. Kidney360 2024, 5, 380–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, M.J.; Quinn, R.R.; Richardson, E.P.; Kiss, A.J.; Lamping, D.L.; Manns, B.J. Home care assistance and the utilization of peritoneal dialysis. Kidney Int. 2007, 71, 673–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verger, C.; Durand, M.P.Y.; Veniez, G.; Fabre, E.; Ryckelynck, J.P. Influence of autonomy and type of home assistance on the prevention of peritonitis in assisted automated peritoneal dialysis patients. An analysis of data from the French Language Peritoneal Dialysis Registry. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2007, 22, 1218–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, E.A.; Dratwa, M.; Povlsen, J. Assisted peritoneal dialysis—An evolving dialysis Modality. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2007, 22, 3091–3092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Béchade, C.; Lobbedez, T.; Ivarsen, P.; Povlsen, J.V. Assisted peritoneal dialysis for older people with End-stage renal disease: The French and Danish experience. Perit. Dial. Int. 2015, 35, 663–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuliani, A.; Karopadi, A.N.; Prieto-Velasco, M.; Manani, S.M.; Crepaldi, C.; Ronco, C. Worldwide experiences with assisted peritoneal dialysis. Perit. Dial. Int. 2017, 37, 503–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, W.F.; Bennett, P.N.; Anwaar, A.; Atwal, J.; Legg, V.; Abra, G.; Zheng, S.; Pravonerov, L.; Schiller, B. Implementation of a Staff-Assisted Peritoneal Dialysis Program in the United States A Feasibility Study. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2022, 17, 703–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliver, M.J.; Salenger, P. Making Assisted Peritoneal Dialysis a Reality in the United States: A Canadian and American Viewpoint. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2020, 15, 566–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliver, M.J.; Abra, G.; Béchade, C.; Brown, E.A.; Sanchez-Escuredo, A.; Johnson, D.W.; Guedes, A.M.; Graham, J.; Fernandes, N.; Jha, V.; et al. Assisted peritoneal dialysis: Position paper for the ISPD. Perit. Dial. Int. 2024, 44, 160–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Educational Barriers | Possible Action Plans |

| Patient education | Easily accessible Internet resource center, linked sites, chat arrangements |

| Physician education | Mandatory training for program certification; ongoing and immersion courses: local, regional, and national |

| Dialysis staff education | Designated time and resources; certification; centers of excellence |

| Governmental Barriers | Possible Action Plans |

| Visit requirements | Local lab services; all frequencies determined by clinical need |

| Dialysis access payment | Align payment incentives for the best access for that patient; awareness of retroactive payment for home dialysis initiates |

| Partner support | Cost analysis and feasibility study |

| Accreditation and certification | Eliminate differences between CMS and The Joint Commission regulations; define precise time frame for certification |

| Staff home visits | Clinical judgment defines necessity; use phone photographs |

| Make available “state-of-the-art” equipment | FDA to streamline approval process; encourage efficiency research; industry–government collaboration |

| Provider Organization Barriers | Possible Action Plans |

| Availability of solutions and equipment | Eliminate inappropriate restriction policies; clinical judgment prevails |

| Delivery of supplies | Accommodate unique patient needs; local and regional depots |

| Pharmacy | Prompt and efficient drug delivery and availability; address and alleviate The Joint Commission restrictions and requirements |

| Business conflicts to patient care | Patient care takes priority |

| Laboratory services | Improve data sharing; more raid-specific responses |

| Quality improvement | Select meaningful data; standardize data collection and reporting |

| Independence | Recommended; encourages problem solving andcreativity but does not occur in a vacuum |

| Physical environment | Appreciate home programs’ unique requirements |

| Staffing | Discourage boilerplate thinking; develop criteria for appropriate staffing ratios; consolidate programs; share staff |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Golper, T.A. Annotated Barriers to Peritoneal and Home Hemodialysis in the U.S. Kidney Dial. 2025, 5, 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/kidneydial5020018

Golper TA. Annotated Barriers to Peritoneal and Home Hemodialysis in the U.S. Kidney and Dialysis. 2025; 5(2):18. https://doi.org/10.3390/kidneydial5020018

Chicago/Turabian StyleGolper, Thomas A. 2025. "Annotated Barriers to Peritoneal and Home Hemodialysis in the U.S." Kidney and Dialysis 5, no. 2: 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/kidneydial5020018

APA StyleGolper, T. A. (2025). Annotated Barriers to Peritoneal and Home Hemodialysis in the U.S. Kidney and Dialysis, 5(2), 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/kidneydial5020018