Barriers to Contraceptive Access in Nigeria During COVID-19: Lessons for Future Crisis Preparedness

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Study Population

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

2.4. Sampling and Recruitment

2.5. Data Collection Instrument

2.6. Variables and Measures

2.6.1. Dependent Variable

2.6.2. Independent Variables

2.7. Bias Control and Sample Size Determination

2.8. Data Management and Analysis

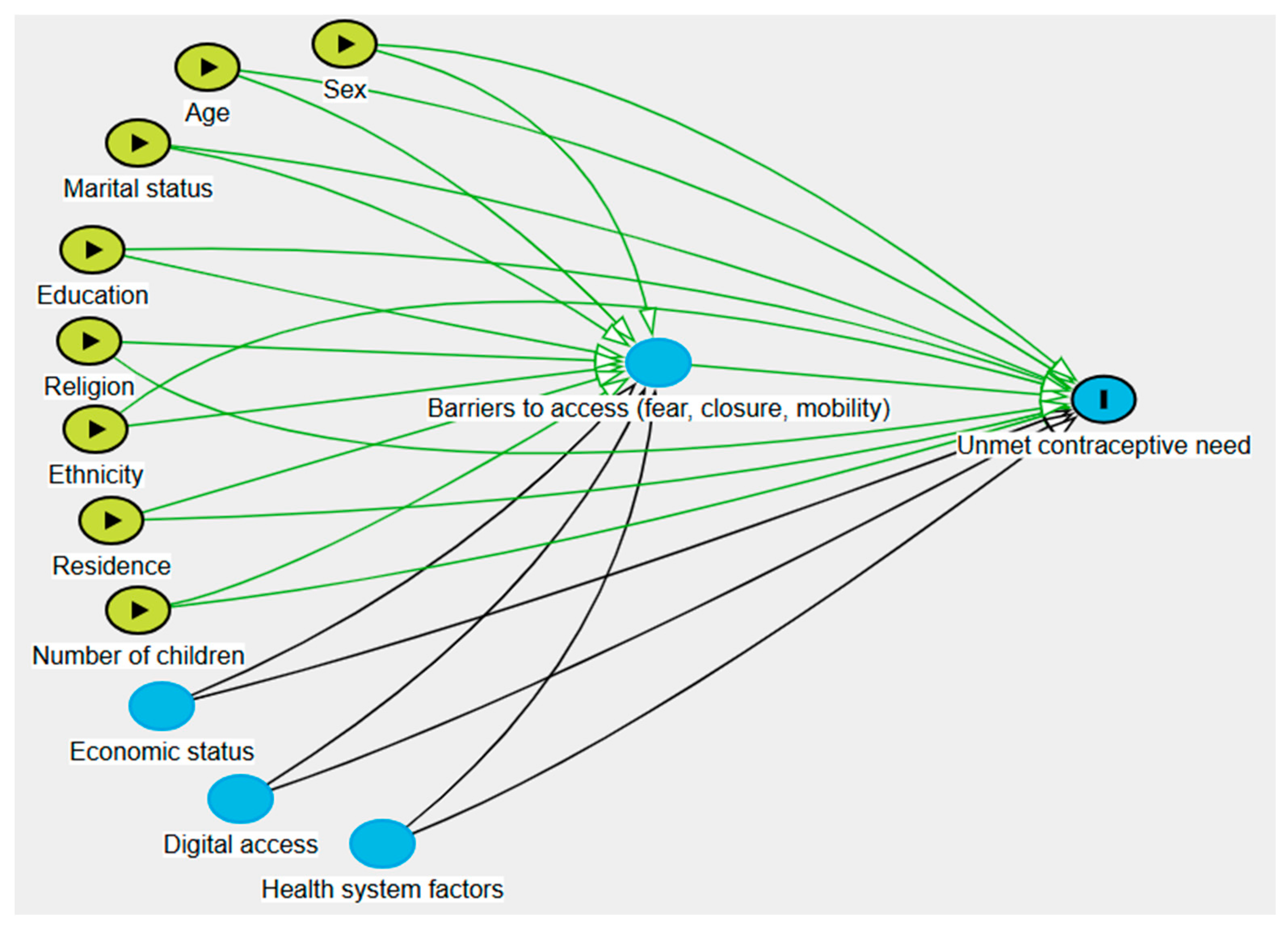

2.9. Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG) Construction

2.10. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Participants’ Socio-Demographic Characteristics

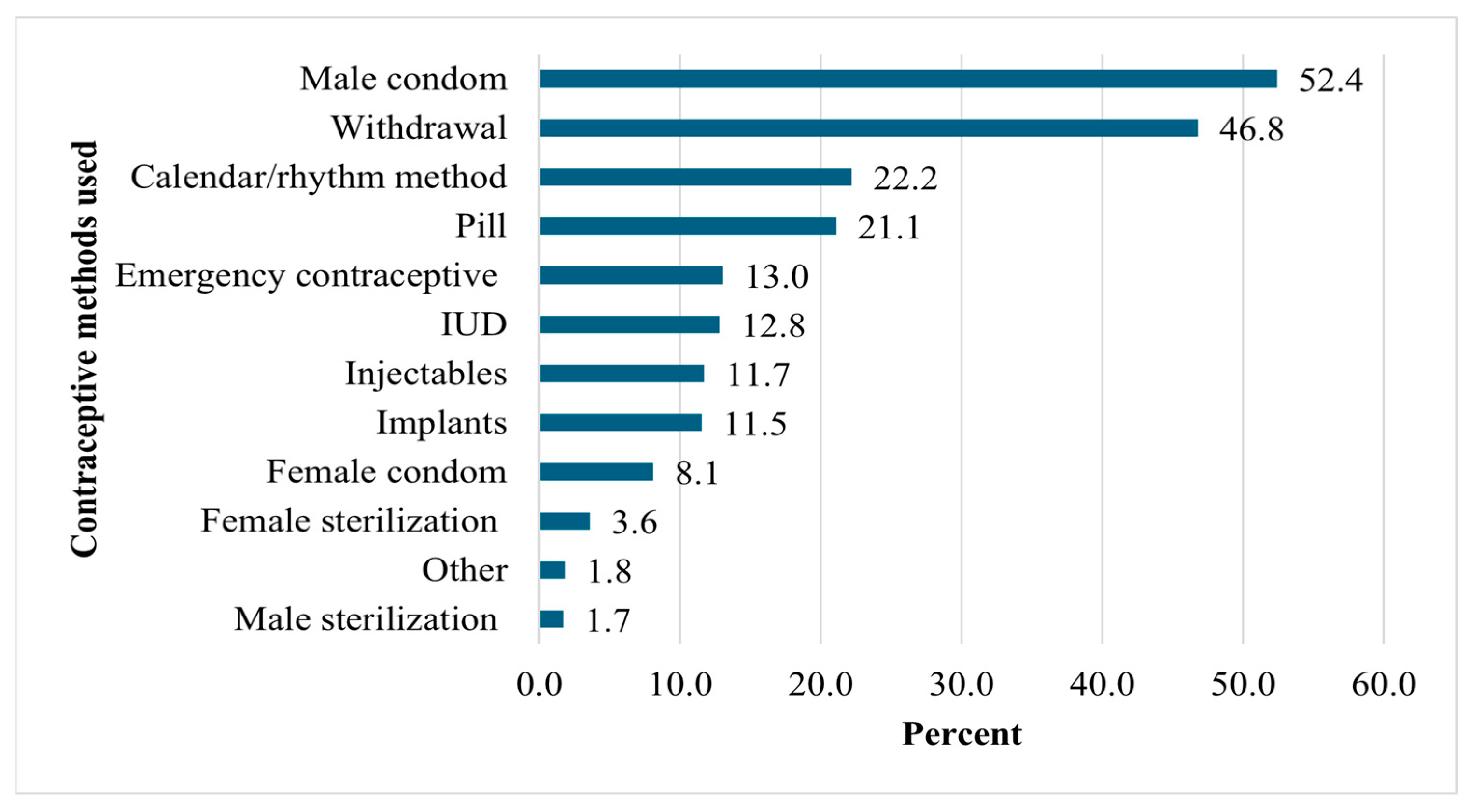

3.2. Contraceptive Methods Previously Used

3.3. Barriers to Access During the COVID-19 Lockdown

3.4. Predictors of Unmet Contraceptive Need

- Model 1 χ2 = 321.76 ***; Nagelkerke R2 = 0.276; -2LL = 1608.12.

- Model 2 χ2 = 328.41 ***; Nagelkerke R2 = 0.281; -2LL = 1601.92.

- Model 3 χ2 = 411.03 ***; Nagelkerke R2 = 0.340; -2LL = 1519.11.

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

4.2. Lessons for Future Crisis Preparedness

4.3. Implications for Policy, Research, and Practice

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sully, E.; Biddlecom, A.; Darroch, J.; Riley, T.; Ashford, L.; Lince-Deroche, N.; Firestein, L.; Murro, R. Adding It Up: Investing in Sexual and Reproductive Health 2019; Guttmacher Institute: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Pujolar, G.; Oliver-Anglès, A.; Vargas, I.; Vázquez, M.-L. Changes in Access to Health Services during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chippaux, J.-P. COVID-19 Impacts on Healthcare Access in Sub-Saharan Africa: An Overview. J. Venom. Anim. Toxins Incl. Trop. Dis. 2023, 29, e20230002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNFPA One Year into the Pandemic, UNFPA Estimates 12 Million Women Have Seen Contraceptive Interruptions, Leading to 1.4 Million Unintended Pregnancies. Available online: https://www.unfpa.org/news/one-year-pandemic-unfpa-estimates-12-million-women-have-seen-contraceptive-interruptions (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Riley, T.; Sully, E.; Ahmed, Z.; Biddlecom, A. Estimates of the Potential Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Sexual and Reproductive Health In Low-and Middle-Income Countries Impacts of the Pandemic on SRH Outcomes. Int. Perspect. Sex. Reprod. Health 2020, 46, 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolarinwa, O.A.; Odimegwu, C.; Ajayi, K.V.; Oni, T.O.; Sah, R.K.; Akinyemi, A. Barriers and Facilitators to Accessing and Utilising Sexual and Reproductive Health Services during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Africa: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2024, 24, 1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Grace, K.; Boyle, E.H.; Mikal, J.P.; Gunther, M.; Kristiansen, D. COVID-19 and Contraceptive Use in Two African Countries: Examining Conflicting Pressures on Women. Popul. Dev. Rev. 2024, 50, 395–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuria-Ndiritu, S.; Karanja, S.; Mubita, B.; Kapsandui, T.; Kutna, J.; Anyona, D.; Murerwa, J.; Ferguson, L. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic and Policy Response on Access to and Utilization of Reproductive, Maternal, Child and Adolescent Health Services in Kenya, Uganda and Zambia. PLoS Glob. Public Health 2024, 4, e0002740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murewanhema, G.; Mpabuka, E.; Moyo, E.; Tungwarara, N.; Chitungo, I.; Mataruka, K.; Gwanzura, C.; Musuka, G.; Dzinamarira, T. Accessibility and Utilization of Antenatal Care Services in Sub-Saharan Africa during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Rapid Review. Birth 2023, 50, 496–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, T.O.; Ekpenyong, A.S.; Nwokocha, E.E. Women’s Empowerment and Sexual Autonomy in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Survey Based Analysis of 22 Countries. Sex. Gend. Policy 2025, 8, e70008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ung, M.; Lam, S.T.; Tuot, S.; Chhoun, P.; Prum, V.; Nagashima-Hayashi, M.; Neo, P.; Marzouk, M.; Durrance-Bagale, A.; De Beni, D.; et al. Sexual and Reproductive Health Services Access and Provision in Cambodia during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Mixed-Method Study of Urban–Rural Differences. Reprod. Health 2023, 20, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prusty, R.K.; Khan, S.; MK, B.; Tandon, D.; Kabra, R.; Allagh, K.P.; Joshi, B. Client Perspectives on Barriers and Facilitators to Avail Family Planning Services During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Maharashtra, India: A Qualitative Study. J. Health Manag. 2025, 27, 533–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahamondes, L.; Cecatti, J.G.; Munezero, A.; Soeiro, R.E.; Fernandes, K.G.; Haddad, S.M.; Bento, S.F.; Padua, K.S.; Zotareli, V.; Charles, C.M.; et al. Disruption and Recovery of Family Planning, Contraception and Other Sexual and Reproductive Health Services in Brazil with COVID-19 Pandemic: A Mixed Methods Approach. Reprod. Health 2025, 22, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leon-Larios, F.; Silva Reus, I.; Lahoz Pascual, I.; Quílez Conde, J.C.; Puente Martínez, M.J.; Gutiérrez Ales, J.; Correa Rancel, M. Women’s Access to Sexual and Reproductive Health Services during Confinement Due to the COVID-19 Pandemic in Spain. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 4074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worldometer Nigeria Population. 2025. Available online: https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/nigeria-population/ (accessed on 8 July 2025).

- National Population Commission (NPC) [Nigeria]; ICF. Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey 2018; NPC: Abuja, Nigeria, 2019.

- Esievoadje, E.S.; Odimegwu, C.L.; Agoyi, M.O.; Jimoh, A.O.; Emeagui, O.D.; Emeribe, N.; Ogbonna, V.I.; Oseji, M.; Buowari, D.Y. Accessibility and Utilization of Family Planning Services in Nigeria During the Coronavirus Disease-2019 Pandemic. Niger. J. Med. 2022, 31, 133–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyewo, E. Systemic Effects on Access to and Utilization of Quality Contraceptive Services by Women of Reproductive Age During Covid-19 Pandemics in Oyo State, Nigeria. Texila Int. J. Public Health 2022, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folayan, M.O.; Arije, O.; Enemo, A.; Sunday, A.; Muhammad, A.; Nyako, H.Y.; Abdullah, R.M.; Okiwu, H.; Undelikwo, V.A.; Ogbozor, P.A.; et al. Factors Associated with Poor Access to HIV and Sexual and Reproductive Health Services in Nigeria for Women and Girls Living with HIV during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Afr. J. AIDS Res. 2022, 21, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adelekan, B.; Ikuteyijo, L.; Goldson, E.; Abubakar, Z.; Adepoju, O.; Oyedun, O.; Adebayo, G.; Dasogot, A.; Mueller, U.; Fatusi, A.O. When One Door Closes: A Qualitative Exploration of Women’s Experiences of Access to Sexual and Reproductive Health Services during the COVID-19 Lockdown in Nigeria. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adefalu, A.; Bankole, O.; Olabode, F.; Afolabi, M.; Buba, M.; Dafe, V.; Kalu, M.; Watkins, E. Influence of Movement Restriction During the COVID-19 Pandemic on Uptake of DMPA-SC and Other Injectable Contraceptive Methods in Nigeria. Open Access J. Contracept. 2025, 16, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adelekan, B.; Goldson, E.; Ntoimo, L.F.C.; Adonri, O.; Aliyu, Y.; Onoja, M.; Araoyinbo, I.; Anakhuekha, E.; Mueller, U.; Ekwere, E.-O.; et al. Clients’ Perspectives on the Utilization of Reproductive, Maternal, Neonatal, and Child Health Services in Primary Health Centers during COVID-19 Pandemic in 10 States of Nigeria: A Cross-Sectional Study. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0288714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samson, T.; Omoyajowo, A.; Adeleke, O. Contraceptive Use and Its Associated Factors in Nigeria: Evidence from during and after COVID-19. Babcock Univ. Med. J. 2025, 8, 348–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunie, A.; Austin, G.; Arkin, J.; Archie, S.; Amongin, D.; Ndejjo, R.; Acharya, S.; Thapa, B.; Brittingham, S.; McLain, G.; et al. Women’s Experiences With Family Planning Under COVID-19: A Cross-Sectional, Interactive Voice Response Survey in Malawi, Nepal, Niger, and Uganda. Glob. Health Sci. Pract. 2022, 10, e2200063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan, R.L.; Cartwright, A.F.; Beksinska, M.; Kasaro, M.; Tang, J.H.; Milford, C.; Wong, C.; Velarde, M.; Maphumulo, V.; Fawzy, M.; et al. Contraceptive Access and Use before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Mixed-Methods Study in South Africa and Zambia. Gates Open Res. 2024, 7, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavagnis, S.; Ryan, R.; Mussa, A.; Hargreaves, J.R.; Tucker, J.D.; Morroni, C. Disparities in Adult Women’s Access to Contraception during COVID-19: A Multi-Country Cross-Sectional Survey. Front. Glob. Women’s Health 2024, 5, 1235475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michael, T.O.; Agbana, R.D.; Ojo, T.F.; Kukoyi, O.B.; Ekpenyong, A.S.; Ukwandu, D. COVID-19 Pandemic and Unmet Need for Family Planning in Nigeria. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2021, 40, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespi, S.; Cambron-Mellott, M.J.; Yong, C.; Balkaran, B.L. Contraceptive Access and Use of Long-Acting Reversible Contraceptives during the COVID-19 Pandemic and Beyond. Women’s Health 2025, 21, 17455057251351740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nkweleko Fankam, F.; Ugarte, W.; Akilimali, P.; Ewane Etah, J.; Åkerman, E. COVID-19 Pandemic Hits Differently: Examining Its Consequences for Women’s Livelihoods and Healthcare Access—A Cross-Sectional Study in Kinshasa DRC. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e072869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asogwa, U.S.; Okafor, N.I.; Ajaero, C.K. COVID-19 and Access to Sexual and Reproductive Health Services: Perspectives from Adolescents and Women in Rural Areas of Enugu State, Nigeria. Int. J. Popul. Stud. 2023, 10, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenbroucke, J.P.; von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Pocock, S.J.; Poole, C.; Schlesselman, J.J.; Egger, M.; Blettner, M.; et al. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): Explanation and Elaboration. Int. J. Surg. 2014, 12, 1500–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, T.O.; Funmilola Ojo, T.; Scent, G.A.T.; Kukoyi, O.B.; Alhassan, O.I.; Agbana, R.D. COVID-19 Health Knowledge and Practices among Nigerian Residents during the Second Wave of the Pandemic: A Quick Online Cross-Sectional Survey. Afr. J. Health Sci. 2021, 34, 482–497. [Google Scholar]

- Sigdel, A.; Bista, A.; Sapkota, H.; van Teijlingen, E. Barriers in Accessing Family Planning Services in Nepal during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Qualitative Study. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0285248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, M.; Lam, S.T.; Durrance-Bagale, A.; Nagashima-Hayashi, M.; Neo, P.; Ung, M.; Zaseela, A.; Aribou, Z.M.; Agarwal, S.; Howard, N. Effects of COVID-19 on Sexual and Reproductive Health Services Access in the Asia-Pacific Region: A Qualitative Study of Expert and Policymaker Perspectives. Sex. Reprod. Health Matters 2023, 31, 2247237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhaji, M.M.; Balarabe, M.R.; Atama, D.; Okafor, A.; Solana, D.; Meyo, F.; Okoye, C.J.; Okafor, U.; Oyelana, B.; Anyanti, J. Motivators and Barriers to the Uptake of Digital Health Platforms for Family Planning Services in Lagos, Nigeria: A Mixed-Methods Study. Digit. Health 2025, 11, 20552076251349624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comfort, A.B.; Rao, L.; Goodman, S.; Raine-Bennett, T.; Barney, A.; Mengesha, B.; Harper, C.C. Assessing Differences in Contraceptive Provision through Telemedicine among Reproductive Health Providers during the COVID-19 Pandemic in the United States. Reprod. Health 2022, 19, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel Tawab, N.; Tayel, S.A.; Radwan, S.M.; Ramy, M.A. The Effects of COVID-19 Pandemic on Women’s Access to Maternal Health and Family Planning Services in Egypt: An Exploratory Study in Two Governorates. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2024, 24, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juliato, C.R.T.; Laporte, M.; Surita, F.; Bahamondes, L. Barriers to Accessing Post-Pregnancy Contraception in Brazil: The Impact of COVID-19. Best. Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2024, 94, 102482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osadebe, N.; Ajaero, C.K.; Asogwa, U.S.; Onuh, J.C. Access to Contraceptives amidst COVID-19 Pandemic in South Africa. IKENGA Int. J. Inst. Afr. Stud. 2025, 26, 241–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomons, N.; Gihwala, H. The Provision of Safe and Legal Abortion Services in South Africa: Expanding Access Through Telemedicine and Lessons Learned During the Covid-19 Pandemic. In Reproductive Health and Assisted Reproductive Technologies in Sub-Saharan Africa; Palgrave Macmillan: Singapore, 2023; pp. 73–101. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson, S.; Rennie, N.; Mann, S.; McCarthy, O.; Palmer, M.; French, R.S. Preference for Face-to-Face Contraceptive Service Delivery Post-COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Study. BJOG 2025, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Govender, D.; Naidoo, S.; Taylor, M. Don’t Let Sexual and Reproductive Health Become Collateral Damage in the Face of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Public Health Perspective. Afr. J. Reprod. Health 2020, 24, 56–63. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34077054/ (accessed on 17 August 2024).

- World Health Organization. SDG Target 3.7 Sexual and Reproductive Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/topics/sdg-target-3_7-sexual-and-reproductive-health (accessed on 17 August 2024).

| Characteristics | Total n (%) | Unmet Need No n (%) | Unmet Need Yes n (%) | χ2 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 4.21 | 0.040 * | |||

| Male | 671 (52.7) | 416 (61.9) | 255 (38.0) | ||

| Female | 602 (47.3) | 322 (53.5) | 280 (46.5) | ||

| Age (years) | 12.58 | 0.014 * | |||

| 18–25 | 89 (7.0) | 61 (68.5) | 28 (31.5) | ||

| 26–33 | 546 (42.9) | 300 (54.9) | 246 (45.1) | ||

| 34–41 | 393 (30.9) | 227 (57.8) | 166 (42.2) | ||

| 42–49 | 215 (16.9) | 128 (59.5) | 87 (40.5) | ||

| 50+ | 30 (2.4) | 22 (73.3) | 8 (26.7) | ||

| Marital Status | 25.67 | <0.001 *** | |||

| Single | 440 (34.6) | 307 (69.8) | 133 (30.2) | ||

| Married | 746 (58.6) | 381 (51.1) | 365 (48.9) | ||

| Cohabiters | 64 (5.0) | 36 (56.2) | 28 (43.8) | ||

| Divorced/separated | 23 (1.8) | 14 (60.9) | 9 (39.1) | ||

| Education | 18.34 | <0.001 *** | |||

| Primary | 103 (8.1) | 48 (46.6) | 55 (53.4) | ||

| Secondary | 137 (10.8) | 72 (52.6) | 65 (47.4) | ||

| Tertiary | 1032 (81.1) | 617 (59.8) | 415 (40.2) | ||

| Religion | 3.92 | 0.141 | |||

| Christianity | 836 (65.7) | 493 (59.0) | 343 (41.0) | ||

| Islam | 416 (32.7) | 235 (56.5) | 181 (43.5) | ||

| Other | 20 (1.6) | 9 (45.0) | 11 (55.0) | ||

| Ethnicity | 22.71 | <0.001 *** | |||

| Hausa | 224 (17.6) | 152 (67.9) | 72 (32.1) | ||

| Yoruba | 615 (48.3) | 326 (53.0) | 289 (47.0) | ||

| Igbo | 165 (13.0) | 94 (57.0) | 71 (43.0) | ||

| Other | 270 (21.2) | 167 (61.9) | 103 (38.1) | ||

| Residence | 15.49 | <0.001 *** | |||

| Urban | 906 (71.2) | 503 (55.5) | 403 (44.5) | ||

| Suburban | 163 (12.8) | 87 (53.4) | 76 (46.6) | ||

| Rural | 205 (16.1) | 149 (72.7) | 56 (27.3) | ||

| No. of children born | 29.83 | <0.001 *** | |||

| 0 | 493 (38.7) | 336 (68.2) | 157 (31.8) | ||

| 1–2 | 392 (30.8) | 207 (52.8) | 185 (47.2) | ||

| 3–4 | 288 (22.6) | 148 (51.4) | 140 (48.6) | ||

| 5 or more | 102 (8.0) | 49 (48.0) | 53 (52.0) |

| Characteristics | Model 1 OR (95% CI) | Model 2 OR (95% CI) | Model 3 OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Male (ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Female | 0.77 (0.60–1.00) | 0.90 (0.64–1.09) | |

| Age group (years) | |||

| 18–25 (ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| 26–33 | 2.04 ** (1.17–3.64) | 2.00 * (1.05–3.73) | |

| 34–41 | 2.24 ** (1.15–3.95) | 1.84 (0.85–3.33) | |

| 42+ | 1.14 (0.58–2.18) | 0.85 (0.37–1.78) | |

| Marital status | |||

| Single (ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Married/cohabiting | 7.25 *** (4.94–10.41) | 3.87 *** (2.58–5.68) | |

| Divorced/separated | 0.88 (0.33–2.18) | 0.65 (0.21–1.78) | |

| Education | |||

| Below tertiary (ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Tertiary | 0.38 *** (0.20–0.66) | 0.28 *** (0.13–0.55) | |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Hausa (ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Yoruba | 2.75 *** (1.69–4.14) | 1.70 * (1.04–2.58) | |

| Igbo | 2.03 ** (1.33–3.44) | 1.83 * (1.05–2.92) | |

| Other | 2.75 *** (1.73–4.26) | 2.24 ** (1.35–3.48) | |

| Residence | |||

| Urban (ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Suburban | 1.32 (0.91–1.89) | 1.54 (1.02–2.27) | |

| Rural | 0.51 *** (0.36–0.73) | 0.57 ** (0.37–0.86) | |

| Number of children | |||

| 0 (ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| 1–2 | 7.71 *** (5.80–9.42) | 2.96 *** (1.90–4.63) | |

| 3–4 | 7.58 *** (5.36–10.16) | 4.04 *** (2.40–6.49) | |

| 5+ | 1.26 (0.74–1.93) | 0.24 * (0.06–0.87) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Michael, T.O. Barriers to Contraceptive Access in Nigeria During COVID-19: Lessons for Future Crisis Preparedness. COVID 2025, 5, 160. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid5090160

Michael TO. Barriers to Contraceptive Access in Nigeria During COVID-19: Lessons for Future Crisis Preparedness. COVID. 2025; 5(9):160. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid5090160

Chicago/Turabian StyleMichael, Turnwait Otu. 2025. "Barriers to Contraceptive Access in Nigeria During COVID-19: Lessons for Future Crisis Preparedness" COVID 5, no. 9: 160. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid5090160

APA StyleMichael, T. O. (2025). Barriers to Contraceptive Access in Nigeria During COVID-19: Lessons for Future Crisis Preparedness. COVID, 5(9), 160. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid5090160