Assessment of Disability Occupational and Sociodemographic Correlates in Mayan Communities in Relation to COVID-19 Diagnosis

Abstract

1. Introduction

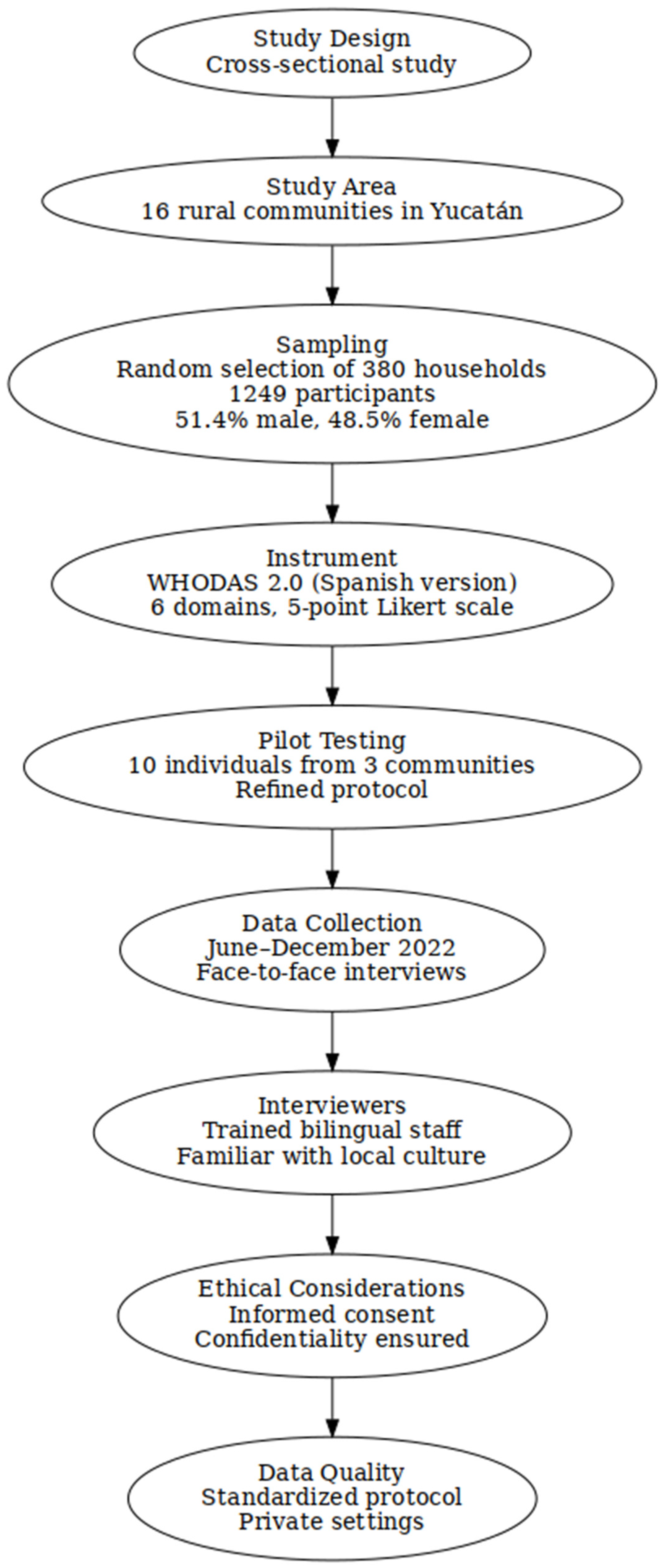

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Participants

2.4. Measures

2.5. Procedure

2.6. Statistical Analysis

2.7. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

4. Discussion

Implications for Rehabilitation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| WHODAS | World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule |

References

- Manyibe, E.O.; Washington, A.L.; Koissaba, B.; Webb, K.; Moore, C.L.; Ward-Sutton, C.; Peterson, G.J. COVID-19 health and rehabilitation implications among multiply marginalized people of color with disabilities: A scoping review. J. Rehabil. 2022, 88, 58–73. [Google Scholar]

- Ala, A.; Wilder, J.; Jonassaint, N.L.; Coffin, C.S.; Brady, C.; Reynolds, A.; Schilsky, M.L. COVID-19 and the uncovering of health care disparities in the United States, United Kingdom and Canada: Call to action. Hepatol. Commun. 2021, 5, 1791–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, C.R.; Feemster, K.A.; Ulloa, E.R. Pediatric COVID-19 health disparities and vaccine equity. J. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. Soc. 2022, 11 (Suppl. S4), S141–S147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Gómez, O.; Medina-Villegas, J.J. Social inequalities in COVID-19 lethality among indigenous peoples in Mexico. Cien Saude Colet. 2024, 29, e05012024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, D.B.G.; Shah, A.; Doubeni, C.A.; Sia, I.G.; Wieland, M.L. The disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on racial and ethnic minorities in the United States. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 72, 703–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero-Rodríguez, E.; Perula-de-Torres, L.Á.; González-Lama, J.; Castro-Jiménez, R.Á.; Jiménez-García, C.; Priego-Pérez, C.; Gonzalez-Bernal, J.J. Long COVID symptomatology and associated factors in primary care patients: The EPICOVID-AP21 study. Healthcare 2023, 11, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, N.S.; Meeks, L.M.; Swenor, B.K. Disability and COVID-19: Who counts depends on who is counted. Lancet Public. Health. 2020, 5, e423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, L.M.; Davey, C.; Shakespeare, T.; Kuper, H. Disability-inclusive responses to COVID-19: Lessons learnt from research on social protection in low- and middle-income countries. World Dev. 2021, 137, 105178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esparza, V.A.; Zambrano, M.C.; Villegas, J.A.; Astudillo, J.R. Desafíos, estrategias y oportunidades emergentes para la salud mental en el contexto de la pandemia de COVID-19. RECIAMUC 2021, 5, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Pacheco, M.; López Sánchez, O. “Enfermó y toda la familia enfermamos, todos colapsamos”. Cuidados en la enfermedad y los impactos en la salud de las madres cuidadoras. Rev. Interdisc. Estud. Genero. Col. Mex. 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ipatov, A.V.; Sanina, N.A.; Khanyukova, I.Y.; Moroz, O.M. The possibilities of disability level determination based on the international classification of functioning with the WHO disability assessment schedule (WHODAS 2.0). Wiad. Lek. 2022, 75, 2086–2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Federici, S.; Bracalenti, M.; Meloni, F.; Luciano, J.V. World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0: An international systematic review. Disabil. Rehabil. 2017, 39, 2347–2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.M.; Stewart, R.; Glozier, N.; Prince, M.; Kim, S.W.; Yang, S.J.; Shin, I.S.; Yoon, J.S. Physical health, depression and cognitive function as correlates of disability in an older Korean population. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. 2005, 20, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Üstün, T.B.; Chatterji, S.; Kostanjsek, N.; Rehm, J.; Kennedy, C.; Epping-Jordan, J.; Saxena, S.; Von Korff, M.; Pull, C. Developing the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0. Bull. World Health Organ. 2010, 88, 815–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willi, S.; Lüthold, R.; Hunt, A.; Hänggi, N.V.; Sejdiu, D.; Scaff, C.; Bender, N.; Staub, K.; Schlagenhauf, P. COVID-19 sequelae in adults aged less than 50 years: A systematic review. Travel. Med. Infect. Dis. 2021, 40, 101995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, V.; Sohaei, D.; Diamandis, E.P.; Prassas, I. COVID-19: From an acute to chronic disease? Potential long-term health consequences. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2021, 58, 297–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babik, I.; Gardner, E.S. Factors affecting the perception of disability: A developmental perspective. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 702166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villarreal-Jimenez, E.; Lores-Peniche, J.A.; Pelaez-Ballestas, I.; Cruz-Martín, G.; Flores-Aguilar, D.; García, H.; Gutiérrez, A.V.; Ayora-Manzano, H.; López, K.; Loyola-Sanchez, A. Co-design of a community-based rehabilitation program to decrease musculoskeletal disabilities in a Mayan-Yucateco municipality. Prog. Community Health Partnersh. 2023, 17, 405–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, K.; Zhang, J.; Liu, M.; Xu, M. The interplay of socioeconomic status, gender, and age in determining physical activity: Evidence from the China Family Panel Studies. Preprints 2023. [CrossRef]

- Alhumaid, M.M.; Said, M.A. Increased physical activity, higher educational attainment, and the use of mobility aid are associated with self-esteem in people with physical disabilities. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1072709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Üstün, T.B. (Ed.) Measuring Health and Disability: Manual for WHO Disability Assessment Schedule WHODAS 2.0; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Henríquez-Thorrens, M.; Donado-Mercado, A.; Lían-Romero, T.; Vidarte-Claros, J.A.; Vélez-Álvarez, C. Determinantes sociales de la salud asociados al grado de discapacidad en la ciudad de Barranquilla. Duazary 2020, 17, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, D.F.; Brown, T.H. Understanding how race/ethnicity and gender define age-trajectories of disability: An intersectionality approach. Soc. Sci. Med. 2011, 72, 1236–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ott, J.; Champagne, S.N.; Bachani, A.M.; Morgan, R. Scoping ‘sex’ and ‘gender’ in rehabilitation: [mis]representations and effects. Int. J. Equity Health. 2022, 21, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Kream, R.M.; Stefano, G.B. Long-term respiratory and neurological sequelae of COVID-19. Med. Sci. Monit. 2020, 26, e928996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeria, M.; Cejudo, J.C.; Deus, J.; Krupinski, J. Neurocognitive and neuropsychiatric sequelae in long COVID-19 infection. Brain Sci. 2024, 14, 604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliberti, M.J.; Bertola, L.; Szlejf, C.; Oliveira, D.; Piovezan, R.D.; Cesari, M.; de Andrade, F.B.; Lima-Costa, M.F.; Perracini, M.R.; Ferri, C.P.; et al. Validating intrinsic capacity to measure healthy aging in an upper middle-income country: Findings from the ELSI-Brazil. Lancet Reg. Health Am. 2022, 12, 100284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzemah-Shahar, R.; Hochner, H.; Iktilat, K.; Agmon, M. What can we learn from physical capacity about biological age? A systematic review. Ageing Res. Rev. 2022, 77, 101609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herold, F.; Theobald, P.; Gronwald, T.; Kaushal, N.; Zou, L.; de Bruin, E.D.; Bherer, L.; Müller, N.G. The best of two worlds to promote healthy cognitive aging: Definition and classification approach of hybrid physical training interventions. JMIR Aging 2024, 7, e56433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León-Herrera, S.; Samper-Pardo, M.; Oliván-Blázquez, B.; Sánchez-Recio, R.; Magallón-Botaya, R.; Sánchez-Arizcuren, R. Loss of socioemotional and occupational roles in individuals with long COVID according to sociodemographic and clinical factors: Secondary data from a randomized clinical trial. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0296041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ervasti, J.; Pietiläinen, O.; Rahkonen, O.; Lahelma, E.; Kouvonen, A.; Lallukka, T.; Mänty, M. Long-term exposure to heavy physical work, disability pension due to musculoskeletal disorders and all-cause mortality: 20-year follow-up—Introducing Helsinki Health Study job exposure matrix. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2019, 92, 337–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greggi, C.; Visconti, V.V.; Albanese, M.; Gasperini, B.; Chiavoghilefu, A.; Prezioso, C.; Persechino, B.; Iavicoli, S.; Gasbarra, E.; Iundusi, R.; et al. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 3964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Álvarez-Sánchez, V.A.; Salcedo-Parra, M.A.; Bonnabel-Becerra, G.; Cortes-Telles, A. Effect of vaccination on COVID-19 mortality during omicron wave among highly marginalized Mexican population. Heliyon 2024, 10, e028781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Domains | Median | Mean | SD | CI 95% | KS | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | z | p-Value | ||||

| Mobility | 1.0 | 1.08 | 0.40 | 1.06 | 1.10 | 0.52 | <0.001 |

| Cognition | 1.0 | 1.03 | 0.22 | 1.02 | 1.04 | 0.52 | <0.001 |

| Community participation | 1.0 | 1.04 | 0.28 | 1.03 | 1.06 | 0.52 | <0.001 |

| Personal care | 1.0 | 1.02 | 0.21 | 1.01 | 1.03 | 0.52 | <0.001 |

| Relationships | 1.0 | 1.01 | 0.15 | 1.00 | 1.02 | 0.52 | <0.001 |

| Daily activities | 1.0 | 1.05 | 0.30 | 1.03 | 1.07 | 0.52 | <0.001 |

| Total WHODAS | 1.0 | 1.04 | 0.21 | 1.03 | 1.05 | 0.49 | <0.001 |

| WHODAS Domains | Age | Educational Years |

|---|---|---|

| Mobility | 0.30 ** | −0.19 ** |

| Cognition | 0.16 ** | −0.12 ** |

| Community participation | 0.23 ** | −0.15 ** |

| Personal care | 0.14 ** | −0.13 ** |

| Relationships | 0.01 | −0.10 ** |

| Daily activities | 0.21 ** | −0.16 ** |

| Total WHODAS | 0.31 ** | −0.27 ** |

| Main Occupation | n | d1 | d2 | d3 | d4 | d5 | d6 | Total WHODAS | Age |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Farmer Cornfield and/or peasant | 184 | 1.09 | 1.01 | 1.03 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.046 | 1.03 | 48.79 |

| Mason | 44 | 1.00 | 1.02 | 1.02 | 1.00 | 1.03 | 1.023 | 1.01 | 40.93 |

| Housewife | 317 | 1.11 | 1.04 | 1.05 | 1.02 | 1.01 | 1.068 | 1.05 | 43.46 |

| Beekeeper | 6 | 1.08 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.000 | 1.01 | 45.5 |

| Craftsman | 59 | 1.11 | 1.05 | 1.08 | 1.04 | 1.04 | 1.085 | 1.07 | 39.19 |

| Salaried worker | 85 | 1.01 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.000 | 1.00 | 32.43 |

| Carpenter | 1 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.000 | 1.00 | 53 |

| Cook | 5 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.000 | 1.00 | 32.4 |

| Merchant | 26 | 1.01 | 1.00 | 1.01 | 1.03 | 1.00 | 1.000 | 1.01 | 42.04 |

| Electrician | 5 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.000 | 1.00 | 32.4 |

| Student | 315 | 1.00 | 1.01 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.02 | 1.016 | 1.01 | 11.16 |

| Blacksmith | 6 | 1.00 | 1.08 | 1.08 | 1.00 | 1.16 | 1.083 | 1.06 | 34.33 |

| Teacher | 3 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.000 | 1.00 | 33 |

| Domestic manufacturing | 8 | 1.06 | 1.00 | 1.06 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.063 | 1.03 | 49.25 |

| Waiter/Dishwasher | 3 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.000 | 1.00 | 25.33 |

| Retired | 3 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.000 | 1.00 | 67 |

| Day laborer | 8 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.000 | 1.00 | 21.88 |

| Plumber | 5 | 1.10 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.000 | 1.01 | 35 |

| Maquiladora industry worker | 2 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.000 | 1.00 | 38 |

| Domestic worker | 13 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.000 | 1.00 | 28.92 |

| Tricycle & motorcycle taxi driver | 5 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.000 | 1.00 | 35.4 |

| Hammock weaving | 28 | 1.41 | 1.05 | 1.19 | 1.17 | 1.05 | 1.143 | 1.17 | 53.43 |

| Crafts vendor | 1 | 2.50 | 1.00 | 2.00 | 3.00 | 1.00 | 1.500 | 1.83 | 66 |

| Shoemaker | 8 | 1.06 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.000 | 1.01 | 42.38 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Estrella-Castillo, D.; Rubio-Zapata, H.; Becerril-García, J.; Lopez-Estrella, A.; Méndez-Domínguez, N. Assessment of Disability Occupational and Sociodemographic Correlates in Mayan Communities in Relation to COVID-19 Diagnosis. COVID 2025, 5, 131. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid5080131

Estrella-Castillo D, Rubio-Zapata H, Becerril-García J, Lopez-Estrella A, Méndez-Domínguez N. Assessment of Disability Occupational and Sociodemographic Correlates in Mayan Communities in Relation to COVID-19 Diagnosis. COVID. 2025; 5(8):131. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid5080131

Chicago/Turabian StyleEstrella-Castillo, Damaris, Héctor Rubio-Zapata, Javier Becerril-García, Armando Lopez-Estrella, and Nina Méndez-Domínguez. 2025. "Assessment of Disability Occupational and Sociodemographic Correlates in Mayan Communities in Relation to COVID-19 Diagnosis" COVID 5, no. 8: 131. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid5080131

APA StyleEstrella-Castillo, D., Rubio-Zapata, H., Becerril-García, J., Lopez-Estrella, A., & Méndez-Domínguez, N. (2025). Assessment of Disability Occupational and Sociodemographic Correlates in Mayan Communities in Relation to COVID-19 Diagnosis. COVID, 5(8), 131. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid5080131