3. Results

On Thursday, 21 February 2020, Lombardy Region, Italy, publicized their first known COVID-19 death and outbreak, which Dr. Lori Lerner read upon waking. She immediately emailed an Italian urology colleague and collaborator, Dr. Richard Naspro, who practiced in Lombardy. On that day, he was underwhelmed: “All is quite similar to normality, apart from a few villages in quarantine. Curfew for public activities (schools, church, big events) should be lifted Monday”.

On Thursday, 28 February 2020, Lori reached out again: “Just checking in. News from Italy doesn’t seem so great”. Richard: “The situation is now dramatic, if not apocalyptic. Our 900-bed hospital has transformed into a COVID-19 hub. We must stay protected from our family (my wife and [newborn] went to our summer house). We have 55 patients intubated in the ICU and more than 200 admitted. All I can tell you is to prepare for the worst and start creating extra places…buy as many masks and gloves as possible. Start making all staff understand what is going to happen because when it starts, it will be difficult to stop”. Lori was stunned. The contrast between the two messages in such a short time was impossible to comprehend.

From that point forward, the Infectious Disease team and two anesthesia colleagues with family in Europe became Lori’s 24 h companions. Calls and texts were exchanged day and night. In Bergamo, Richard shifted to COVID-19-dedicated units, leaving space only for urological emergencies [

2]. Richard managed to stay infection-free and working, informing Lori of new protocols and pivots they had to make.

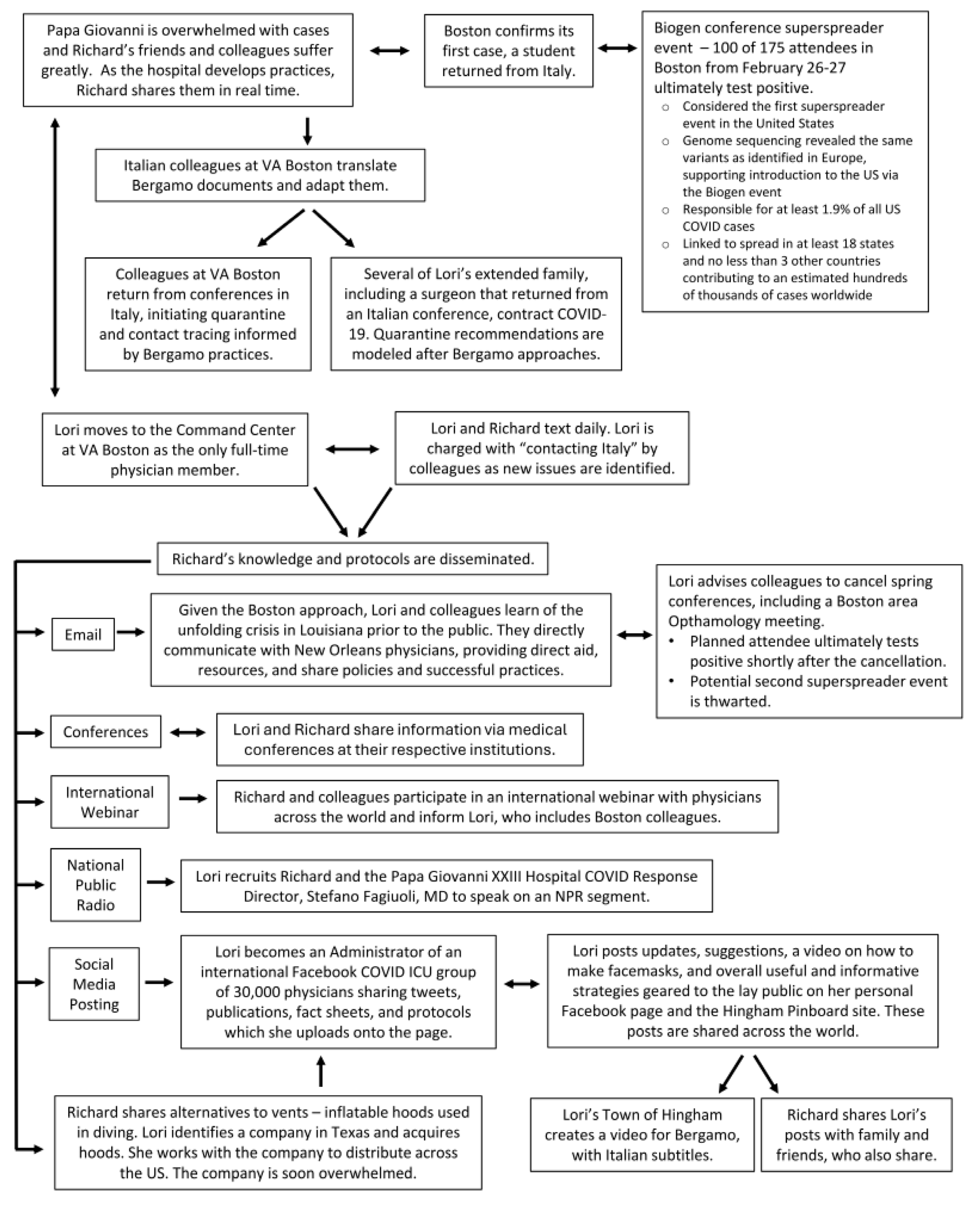

Figure 1 outlines the effects of the Lori-and-Richard connection during the first 2 months of the pandemic, from late February through to April 2020.

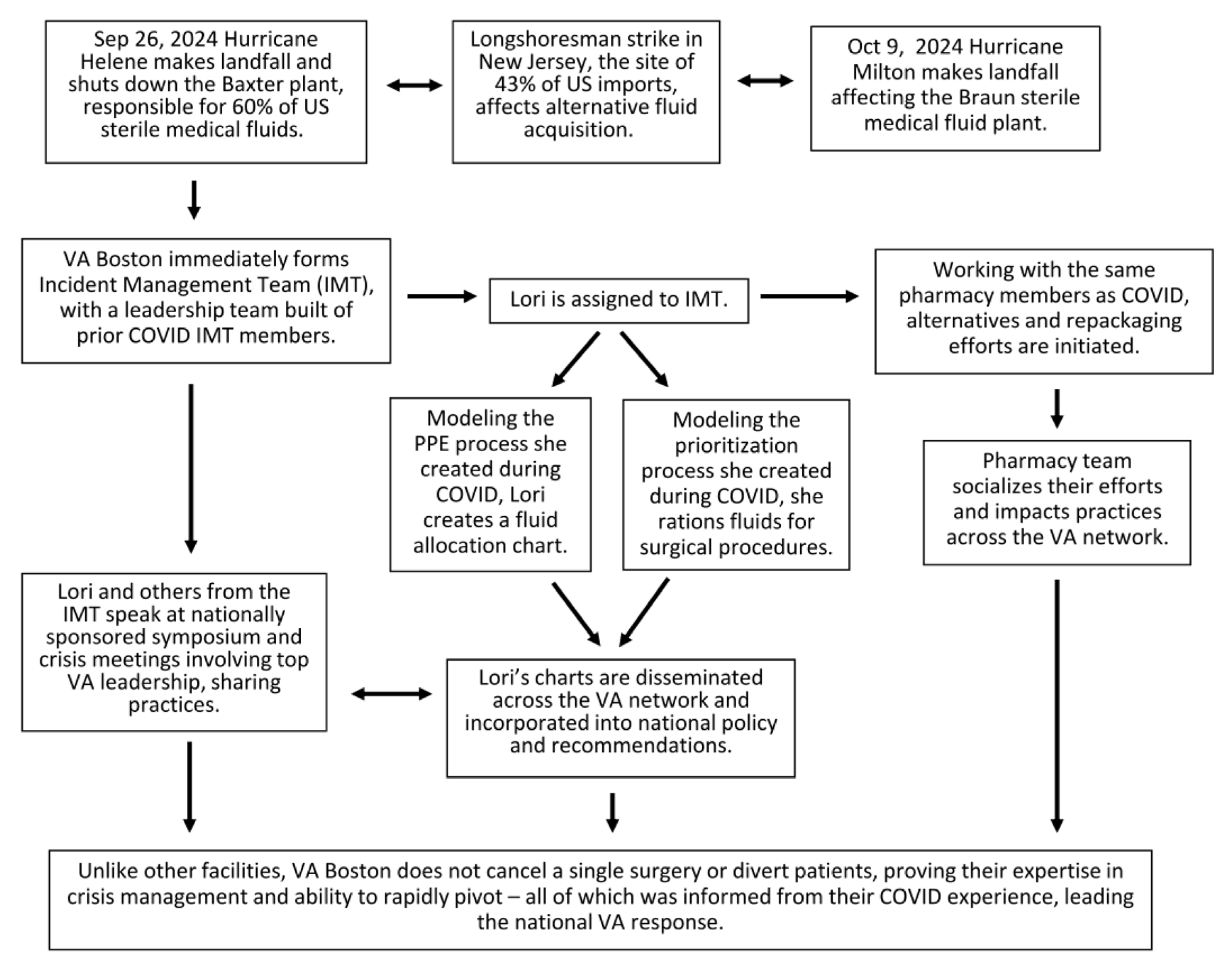

Five years post-pandemic, many of the protocols created during that time remain in place at VA Boston, including those surrounding PPE (personal protective equipment), alternatives to ventilators, and crisis management. Components of the Lori-and-Richard connection informed the crisis response at VA Boston with the Baxter fluid crisis from October 2024 through to February 2025, particularly with prioritization, successful dissemination practices, and communication (

Figure 2) [

4,

5].

4. Discussion

In her article “Autoethnography: The Science of Writing Your Lived Experience”, Susan O’Hara, PhD, MPH, RN, discusses this research method and outlines steps to take when embarking on this approach [

6]. She states, “Autoethnographic writing is a scientific method which contextualizes experiences in cultural, social, political and personal history. Through an evidence-based approach, professionals in academic, practice, and research can bring their past experiences to a place in the present and provide direction for future professionals”. It is the use of personal experiences to inform practice that differentiates autoethnography from autobiography. For Drs. Lerner and Naspro, their social experiment was not necessarily embarked upon initially as a form of research, but along the way, they realized that they were, indeed, conducting research. Using their prior communications and knowledge sharing, they engaged in specific activities that led to the dissemination of knowledge and impacted not only practices but lives. They communicated results to each other and, subsequently, to members of both their hospital and social communities. Their findings were transmitted in real time, became the basis of protocols and actions, and had immediate impact, negating the need to perform more rigorous analysis that could delay information sharing. Farrell et al. describe autoethnography in education as methodology that allows clinician-educators to research their own cultures, sharing insights about their own teaching and learning journeys in ways that will resonate with others” [

7]. For Lori and Richard, both employed in academic centers with medical students and residents, sharing these communications within the context of teaching conferences furthered their impact. Presentations of their communications, protocols, articles, approaches, and outcomes were delivered both in Boston and Bergamo—many elements of which are still in use today, adding legitimacy to this research method and supporting Adams’s sixth tenet of autoethnography: “strives for social justice and to make life better” [

1]. For Richard and Lori, the country, nationality, economic status, or healthcare system did not matter; they and their colleagues were one team, connected across space by a single common foe—SARS-CoV-2. To conquer it was the only option. Further supporting Adams’s tenets of emotion and self-reflection, the Lori-and-Richard and Bergamo-and-Boston connections provided emotional support at many levels—individual, professional, and civic.

Engagement in intimate social interactions and relationships has an important influence on overall well-being. Online friendships can be similar in meaning, intimacy, and stability to conventional offline relationships. Multiple studies have reported positive effects on psychosocial well-being related to online social interactions, including increased self-esteem and self-efficacy, better mood, greater perceived social support, and reduced loneliness, as well as a lower incidence of depression and anxiety [

8]. Advances in Internet-based communication and social networking applications have led to major shifts in the mode of human interactions, exemplified well by the COVID-19 pandemic, with digital platforms being the mainstay of social contact with family, friends, and colleagues. Online psychological crisis intervention strategies for frontline nurses proved beneficial during the pandemic, supporting the value of this mode of connection [

9]. The virtual friendship between Lori and Richard echoed these findings and was an essential aspect to both their lives, helping them maintain emotional stability. Their real-time rapid communication and information sharing provided not only reassurance and support but led to valuable work-centered process development. Richard was able to give insight and offer elements of protocols they developed in Italy that Lori was able to incorporate into her own. As Italy rolled out their protocols ahead of Boston, Lori was given the benefit of time to vet these processes that were informed by what Richard experienced—such as what worked and what did not.

At it’s peak in early April, Papa Giovanni XXIII hospital had >1200 admitted COVID-19 patients, with each freed bed immediately occupied. Their hospital was featured on BBC news as Italy became the epicenter of a more aggressive variant of the virus than what seemed to come from China. Indeed, the west coast of the US was presumed infected via travelers from China, while the East Coast was linked to Italy (Biogen conference superspreader,

Figure 1)—with the morbidity and mortality much more significant in the East [

3,

10,

11]. Fortunately for Lori, Boston never realized the same intensity as Bergamo; and fortunately for both, Lori and Richard carried on symptom-free, checking in daily. Lori grieved Richard’s losses and patients that succumbed, and both celebrated the successes they each experienced. Indeed, the need to interact and share crises is well known. Veterans talk of bonds with fellow soldiers with whom they shared trauma, similarly to those who have experienced disasters. Jaimes et al. described four dynamic poles in clinicians’ narratives when investigating the crisis response in Haiti after the 2010 earthquake [

12]. Clinicians reported “balancing duty and desire to help, experiencing fragility and strength, negotiating separation and connection, and sharing hurt and hope”. Not surprisingly, clinicians considered their work to be a source of strength in the face of adversity. Working together left them with mutual connections and feelings of being intimately intertwined. Richard and Lori not only shared the COVID-19 crisis in their immediate environment but also across the globe. Every morning, each would check WhatsApp. As Richard’s colleagues around him became infected, some critically, and neither Richard nor Lori certain of what was happening to the other, they each feared the morning there would be no message. In contrast to the many Boston hospitals sharing the COVID-19 burden as compared to only one in Bergamo, and the fact that Lori was more protected in both her role and employment at a Veterans Affairs hospital, it seemed inevitable that Richard would ultimately become infected—an anxiety provoking worry for them both. Nonetheless, the emotional support created through their connection provided both hope and answers for not only themselves but for colleagues, friends, and families—anyone with whom they shared their communications.

Unlike Richard, Lori had capacity for projects outside of work. She initiated and led a community response with homemade facemasks, PPE acquisition, and blood drives to support low blood banks. Recognizing Adams’s fourth tenet of authoethnography, “shows people in the process of figuring out what to do, how to live, and the meaning of their struggles” [

1], schools were closed and people stayed at home, unsure of what was coming and needing something to do. This reality provided an opportunity for Lori’s affluent town of 25,000 to contribute in meaningful and, quite frankly, necessary ways. Her community efforts were acknowledged on local radio shows and several local newspapers, drawing attention and recognition to the efforts, resulting in fundraising and increased participation in the projects to further support the cause. Zautra et al. described in their 2010 publication “Resilience: A New Definition of Health for People and Communities” that during crisis, “Mind-body homeostasis is [sustained] by ongoing, purposeful, affective engagement” [

13]. Individual and community responses to adversity, whether health-related or natural disasters, determine resilience and recovery. Themes from this nearly 60-page discourse fueled Lori’s physician-thinking mindset that the duty of a doctor is to heal humans, whether direct patients or members of a shared community. As Bergamo soared towards their peak, Lori posted on Facebook asking her town to send pictures and/or video clips for workers at Papa Giovanni XXIII hospital as they battled on—a message of solidarity from “across the pond”. This tremendous 8 min message expanded the connection of Richard and Lori beyond the two of them and into their communities, acknowledging the contributions of the struggling city (

https://vimeo.com/402367865, accessed on 26 April 2025).

Reflecting on the COVID-19-era events of 5 years ago and what has transpired since, many of the processes and relationships established during that time remain, as exhibited by the recent Baxter sterile fluid crisis. The VA Boston Incident Command Center drew on the expertise, experiences, and protocols developed during the COVID-19 pandemic. Indeed, their ability to stand up a crisis response was significantly ahead of the nation. Similarly to 5 years prior, VA Boston led policy development and guidance released by national offices. The quick response by the Incident Command team allowed VA Boston to proceed with unaltered medical delivery and surgery despite the fluid limitations, a fact not realized by many other hospitals.

The community effort realized in Lori’s hometown in 2020 forged many long-term relationships. In fact, some have led to new business ventures and other community driven efforts. The value of that impact on both the livelihoods of those families, but also those in need who have benefitted from other community initiatives, cannot be minimized. While communities suffered in many ways during the COVID-19 era, these are examples of positive influences that are important to emphasize and can bring hope during future crises.

On a personal level, the relationship developed by Lori and Richard during the COVID-19 pandemic has continued to flourish. Over the years, they have shared many components of their now very different lives. Both have advanced in their careers, seeking advice from the other along the way. Not surprisingly, each have progressed into higher leadership roles as the COVID-19 experience contributed to profound growth in their professional lives in many ways. While the years have brought only one in-person visit, Lori and Richard continue to communicate on a near weekly basis, providing a safe space to discuss work-related challenges and seek advice from a trusted colleague and friend.

The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic proved Margaret Mitchell’s quote: “Life’s under no obligation to give us what we expect” [

14]. But with all crises come opportunities; some aspects are devastating, and others bring growth. As have countless others at the forefront of the COVID-19 pandemic 5 years ago, these two individuals have carried forward their stories and lessons learned as surgeons, physicians, and leaders in their hospitals. The value of their personal connection was seen directly in the creation of protocols and focused efforts that allowed Lori to streamline her hospital practices and not waste time where it was not necessary. For Richard, his colleagues found strength and emotional support in knowing that their experiences were having a direct impact on lives across the globe, which provided them with encouragement and gave them a purpose that expanded beyond just current environment. The impact of their autoethnographic writing has continued to influence current practices at their own hospitals and likely hundreds more given the widespread sharing that occurred across so many different platforms. The positive results of the Lori–Richard “experiment” legitimized and validated the informal approach to seeking out and sharing information outside the context of publications and research and institutional privacy standards.