“The Right to Our Own Body Is Over”: Justifications of COVID-19 Vaccine Opponents on Israeli Social Media

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Facebook Pages

“If you have been affected by the government’s restrictions or believe that the COVID-19 policy compromises democracy, if you have experienced side effects following the vaccine and did not find a sympathetic ear, if you feel that you and your children are experiencing unfair pressure, if you believe that we must all get our lives and routines back, join us. Only if we unite can we return our country to a path of health and sanity” [37].

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

2.4. Ethics

3. Results

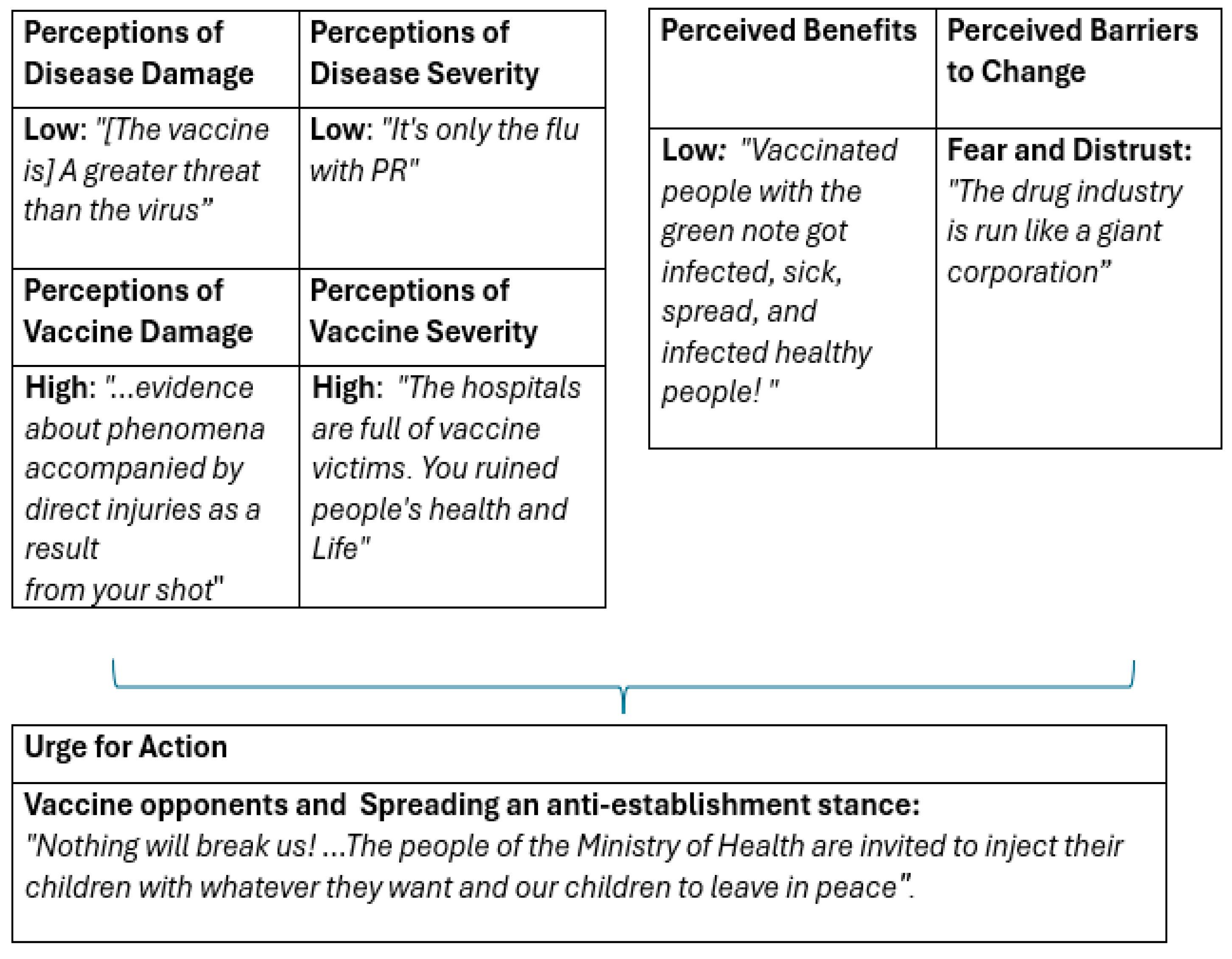

- Theme 1. “[The vaccine is] A greater threat than the virus”: Perceptions of Disease Damage.

“If contagion were so great, we would already be with no transportation. Think about drivers who are so close to people when driving a bus. There are many questions in general regarding this” (PECC, December 2021).

“Over 100 lawyers have mobilized for the fight against child COVID-19 vaccinations, grounding their arguments in the medical professional basis PECC presented. They claim what we all know—there is no emergency situation in Israel; thus, we should not use a vaccine that had only received emergency approval. The vaccine presents a greater threat than the virus” (PECC, June 2021).

“This testimonial project was conceived to provide a platform for all those damaged by the COVID-19 vaccine and give them a voice that Israeli media does not. We hope the project will encourage more and more people to tell their stories”.

“It will do you no good, as there are so many testimonies regarding side effects and direct damage resulting from your injection that [they] will flood the country like a boomerang, a great tsunami; you cannot fight reality” (PECC, July 2021).

- Theme 2. “It’s only the flu with good PR (public relationship)”: Perceptions of Disease Severity.

“An invented virus […] whose existence hasn’t been proven, and emotional assumptions with no factual basis. A group of irresponsible people, greedy and power-hungry, who can only create trash science covered up by cruel arrogance” (MOH, December 2021).

“There’s no morbidity and no Omicron. You invented a word to market the vaccine” (MOH, December 2021).

“The lower public trust gets, the more you try to frighten the public to control it.”

“This disease is so dangerous that you must keep producing ads and campaigns. And I’m thinking—who are these zombies watching this today and swallowing this made-up video?”

“I’m watching the video and thinking that I no longer believe a single word you utter, Ministry of Health” (MOH, February 2021).

“Enough lies. We don’t believe you. The hospitals are full of vaccine victims. You have ruined people’s health and their lives, not to mention the rise in mortality since the vaccines have been introduced. Ask the undertakers. I’ve read quite a few testimonies of people who had been hospitalized or whose families had been, reporting that the wards are full of vaccine victims” (MOH, May 2021).

“[…] In the fall or winter, they will continue vaccinating us. And it will be ten times worse. If they haven’t forced us to become annihilated until now, in two or three months, there will be a mandatory vaccination law and detention centers for the opponents. The same [Prime Minister] Bennet mentioned this once: “Recuperation Facilities” (PECC, August 2021).

- Theme 3. “Vaccinated people with the green note got infected, got sick, spread and infected healthy people!” Perceived Benefits.

“News flash… my children aged four and six have been positive since Sunday, completely non-symptomatic, and my husband and I, who have been vaccinated three times, are sick and symptomatic (MOH, February 2022).

“The Green Pass is life?!?!?! You should be ashamed of yourselves. There’s no forgiveness for the crime you are committing!!! Life is eating right, breathing right, and not being under constant strain because there is a heavy cloud above you forcing you to participate in an experiment that received [only] emergency authorization!!! My uncle received three vaccines and infected half my family over the holiday, and they are not vaccinated… So how does the Green Pass help?!” (MOH, September 2021).

“It seems that most vaccinated people with the Green Pass have gotten sick and passed the disease on to healthy people!! It’s a shame that you need another vaccine every six months, and it still doesn’t prevent contagion!!” (MOH, September 2021).

“In addition to driving people apart, there is nothing here! I know people who have all the vaccinations and have contracted the disease more than once and others who are not being vaccinated who never got it!! Both vaccinated and non-vaccinated people can pass the disease to others, so it’s completely unclear what’s behind all this nonsense you’ve said here” (MOH, September 2021).

- Theme 4. “The drug industry is run like a giant corporation”: Perceived Barriers to Change.

“Facial paralysis, diarrhea, damage to the heart muscle, damage to the placenta for women, you’re liars, you’ll pay for this, shitheads” (MOH, December 2021).

“I’ve met vaccinated people, seen side effects with my own eyes. I’m not getting vaccinated!!! I’m not your lab rat. Lying criminals” (PECC, September 2021).

“It’s really great that in Europe and the US, they stopped the vaccinations and checked. Here, despite cases of myocarditis, they didn’t stop anything to check. Also, regarding post-vaccination paresthesia, many doctors claim that it’s due to anxiety, and some still do. People would have gained more trust if the Ministry of Health had treated these phenomena properly. Also, pay attention to the fact that for two months, they didn’t post presentations of side effects”.

“Is there any reason they don’t publish updates for the follow-up on post-vaccination side effects in Israel? The last report was published on March 1, 2021 (more than two months ago), and did not include a proper, separate, emphasized section regarding post-vaccination cardiac and neurological phenomena”.

“The drug industry is run like a giant corporation raking in billions and employing people who engineer our consciousness and fear who have taken over the media… and along the way, it manages to recruit little politicians who accumulate control and power over a weak, tired population… which is willing to take drugs only so they can feel free… even if it’s at the expense of the freedom to choose what to put into their bodies…. “(PECC, April 2021).

“Unfortunately, the doctors have sold themselves to the government and the drug companies. I have no trust in you. There are more questions than answers regarding the disease and the vaccine” (MOH, February 2021).

“Instead of putting a doctor reading from a prompter here, start publishing data. Prove that there’s no rise in the rate of cardiac cases among young people compared to previous years”. (MOH, November 2021).

“Thank you, PECC. It seems that world governments have fallen in love with the pandemic. I’ve decided it’s all done intentionally, and there’s no way back. The trend is global totalitarianism. It’s amazing how most doctors and journalists worldwide collaborate with this” (PECC, December 2020).

“You, all the doctors and professors who studied at the different academies, following the years in those academies, your brains have shrunk so much that you can’t understand that there’s such a thing as a conspiracy. And what is happening today is one big conspiracy against us. There’s no connection between what is happening here and our health that we’ve already understood. This is an attempt to gain control and turn Israel into a fascist digital dictatorship” (PECC, December 2021).

- Theme 5. “Nothing will break us! [from our firm position]”: Urge for Action.

“The Jewish State is the only one using this fascist selection badge you call a Green Passport. Israeli MOH, you will be remembered in infamy” (MOH, May 2021).

“This Green Patch is shameful. It doesn’t really work in practice. It’s only to make people get vaccinated, and anyone who collaborates with it legitimizes the dictatorship. Today it’s the Green Pass and later on who knows what else they’ll throw at the citizens. Democracy is over and so is our right to our own bodies. Shame” (MOH, May 2021).

“Instead of marketing the Green Patch, tell the people, those you lied to saying the vaccine is safe and has been approved, the many thousands of people suffering from side effects and the huge spike in annual mortality since the beginning of the Pfizer operation. I myself am astounded to discover that nearly every friend or acquaintance I ask about changes in their health following participation in your experiment suffers from “slight” or serious side effects: facial muscle paralysis, paresthesia, different neurological phenomena, strangulation sensations, stroke (which fortunately did not cause death), numb arms, nausea, dizziness, serious weakness, pneumonia, strange swellings, and many other terrible things. Unfortunately, some people don’t want to think there’s a connection between their deteriorating health and the vaccine. Your brainwashing worked great” (MOH, May 2021).

“The MOH people are welcome to inject their own children with whatever they wish and leave ours alone. We will take advice from healthcare professionals who care about our children’s health rather than foreign interests” (MOH, November 2021).

“A 12-year-old child died four days after the vaccine. The family was offered a bribe not to talk” (PECC, March 2022).

“As hard as you can!!! There are already murder victims” (PECC, December 2021).

“Today, I understand that all you care about is that we become as sick as possible. Otherwise, how will you make money if we’re healthy??? I’m proud of all my family who are not vaccinated! My parents, my husband, my children, my sisters, my nephews! And nothing, but nothing will break us!!!” (MOH, December 2021).

“In my opinion, the number of dead due to COVID-19 “vacspiracy” (The word in Hebrew was shcorona, a portmanteau of sheker (lie) and Corona.) is much higher than 300,000” (PECC, April 2022).

4. Discussion

4.1. The Perception of the Threat of a Disease

4.2. Emotional and Cognitive Barriers to Change and Response to Vaccination

4.3. Urge for Action of the Commenters by Resisting the Vaccines and Publicizing Their Stance on Social Media

4.4. Theoretical and Managerial Implications

5. Conclusions

Limitations and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bord, S.; Satran, C.; Schor, A. The mediating role of the perceived COVID-19 vaccine benefits: Examining Israeli parents’ perceptions regarding their adolescents’ vaccination. Vaccines 2022, 10, 917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puri, N.; Coomes, E.A.; Haghbayan, H.; Gunaratne, K. Social media and vaccine hesitancy: New updates for the era of COVID-19 and globalized infectious diseases. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2020, 16, 2586–2593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuchat, A. Human vaccines and their importance to public health. Procedia Vaccinol. 2011, 5, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, D.A.; Mohr, K.S.; Barjaková, M.; Lunn, P.D. A lack of perceived benefits and a gap in knowledge distinguish the vaccine hesitant from vaccine accepting during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol. Med. 2021, 53, 3238–3241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limbu, Y.B.; Gautam, R.K.; Pham, L. The health belief model applied to COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: A systematic review. Vaccines 2022, 10, 973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gendler, Y.; Ofri, L. Investigating the Influence of Vaccine Literacy, Vaccine Perception, and Vaccine Hesitancy on Israeli Parents’ Acceptance of the COVID-19 Vaccine for Their Children: A Cross-Sectional Study. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, M.S.; Abdullah, R.; Vered, S.; Nitzan, D. A study of ethnic, gender and educational differences in attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccines in Israel—Implications for vaccination implementation policies. Isr. J. Health Policy Res. 2021, 10, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freeman, D.; Loe, B.S.; Chadwick, A.; Vaccari, C.; Waite, F.; Rosebrock, L.; Lambe, S. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in the UK: The Oxford coronavirus explanations, attitudes, and narratives survey (Oceans) II. Psychol. Med. 2022, 52, 3127–3141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shekhar, S.K. Social marketing plan to decrease the COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among senior citizens in rural India. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manolescu, L.S.C.; Zaharia, C.N.; Dumitrescu, A.I.; Prasacu, I.; Radu, M.C.; Boeru, A.C.; Boidache, L.; Nita, I.; Necsulescu, A.; Medar, C.; et al. COVID-19 Parental Vaccine Hesitancy in Romania: Nationwide Cross-Sectional Study. Vaccines 2022, 10, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubé, E.; Vivion, M.; MacDonald, N.E. Vaccine hesitancy, vaccine refusal, and the anti-vaccine movement: Influence, impact, and implications. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2015, 14, 99–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Mathur, M.; Kumar, N.; Rana, R.K.; Tiwary, R.C.; Raghav, P.R.; Kumar, A.; Kapoor, N.; Mathur, M.; Tanu, T.; et al. Understanding the phases of vaccine hesitancy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Isr. J. Health Policy Res. 2022, 11, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenstock, I.M.; Strecher, V.J.; Becker, M.H. Social learning theory and the Health Belief Model. Health Educ. Behav. 1988, 15, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orr, D.; Baram-Tsabari, A.; Landsman, K. Social media as a platform for health-related public debates and discussions: The Polio vaccine on Facebook. Isr. J. Health Policy Res. 2016, 5, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindlof, T.; Taylor, B.C. Qualitative Communication Research Methods, 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Muric, G.; Wu, Y.; Ferrara, E. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy on social media: Building a public Twitter data set of antivaccine content, vaccine misinformation, and conspiracies. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2021, 7, e30642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neely, S.R.; Eldredge, C.; Ersing, R.; Remington, C. Vaccine hesitancy and exposure to misinformation: A survey analysis. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2021, 37, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halperin, D.; Schor, A.; Mashiah Eizenberg, M.; Satran, C.; Ali Salah, A.; Inchi, L.; Bord, S. Examining the response to future vaccination against COVID-19 among the adult population in Israel. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2020, 47, 163–187. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Gächter, A.; Zauner, B.; Haider, K.; Schaffler, Y.; Probst, T.; Pieh, C.; Humer, E. Areas of Concern and Support among the Austrian General Population: A Qualitative Content Analytic Mapping of the Shift between Winter 2020/21 and Spring 2022. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frankenthal, D.; Zatlawi, M.; Karni-Efrati, Z.; Keinan-Boker, L.; Luxenburg, O.; Bromberg, M. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among Israeli adults before and after vaccines’ availability: A cross-sectional national survey. Vaccine 2022, 40, 6271–6276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, W.; Stoker, G.; Bunting, H.; Valgarðsson, V.; Gaskell, J.; Devine, D.; McKay, L.; Mills, M. Lack of trust, conspiracy beliefs, and social media use predict COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. Vaccines 2021, 9, 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garett, R.; Young, S. Online misinformation and vaccine hesitancy. Transl. Behav. Med. 2021, 11, 2194–2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amit Aharon, A. Parents’ decisions not to vaccinate their child: Past and present, characterizing the phenomenon and its causes. Promot. Health Isr. 2011, 4, 32–40. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Bertin, P.; Nera, K.; Delouvée, S. Conspiracy beliefs, rejection of vaccination, and support for hydroxychloroquine: A conceptual replication-extension in the COVID-19 pandemic context. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 565128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewandowsky, S.; Gignac, G.E.; Oberauer, K. The role of conspiracist ideation and worldviews in predicting rejection of science. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e75637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freed, G.; Clarck, S.; Butchart, A.T.; Singer, D.C.; Davis, M. Sources and perceived credibility of vaccine safety information for parents. Pediatrics 2011, 127, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.S.; Kamal, A.; Kabir, A.; Southern, D.L.; Khan, S.H.; Hasan, S.M.; Sarkar, T.; Sharmin, S.; Das, S.; Roy, T.; et al. COVID-19 vaccine rumors and conspiracy theories: The need for cognitive inoculation against misinformation to improve vaccine adherence. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, 0251605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kata, A. Anti-vaccine activists, Web 2.0, and the postmodern paradigm–An overview of tactics and tropes used online by the anti-vaccination movement. Vaccine 2012, 30, 3778–3789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, B.L.; Felter, E.M.; Chu, K.H.; Shensa, A.; Hermann, C.; Wolynn, T.; Primack, B. It’s not all about autism: The emerging landscape of anti-vaccination sentiment on Facebook. Vaccine 2019, 37, 2216–2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Douglas, S.; Laila, A. Among sheeples and antivaxxers: Social media responses to COVID-19 vaccine news posted by Canadian news organizations, and recommendations to counter vaccine hesitancy. Can. Commun. Dis. Rep. 2021, 47, 524–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolotti, A.; Bonetti, L.; Luca, C.E.; Villa, M.; Liptrott, S.J.; Steiner, L.M.; Balice-Bourgois, C.; Biegger, A.; Valcarenghi, D. Nurses Response to the Physical and Psycho-Social Care Needs of Patients with COVID-19: A Mixed-Methods Study. Healthcare 2024, 12, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jou, Y.-T.; Mariñas, K.A.; Saflor, C.S.; Young, M.N.; Prasetyo, Y.T.; Persada, S.F. Factors Affecting Perceived Effectiveness of Government Response towards COVID-19 Vaccination in Occidental Mindoro, Philippines. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meraya, A.M.; Salami, R.M.; Alqahtani, S.S.; Madkhali, O.A.; Hijri, A.M.; Qassadi, F.A.; Albarrati, A.M. COVID-19 Vaccines and Restrictions: Concerns and Opinions among Individuals in Saudi Arabia. Healthcare 2022, 10, 816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Der Pijl, M.S.G.; Hollander, M.H.; Van Der Linden, T.; Verweij, R.; Holten, L.; Kingma, E.; Verhoeven, C. Left powerless: A qualitative social media content analysis of the Dutch #breakthesilence campaign on negative and traumatic experiences of labour and birth. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0233114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MIDAAT. Available online: https://www.midaat.org.il/midaat/ (accessed on 2 May 2023).

- MIDAAT. Available online: https://www.midaat.org.il/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/vsn-banner-2.png (accessed on 2 May 2023).

- PECC. Available online: https://www.pecc.org.il/ (accessed on 2 May 2023).

- Maiman, L.A.; Becker, M.H. The Health Belief Model: Origins and Correlates in Psychological Theory. Health Educ. Monogr. 1974, 2, 336–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochbaum, G.M. Why people seek diagnostic X-rays. Public Health Rep. 1956, 71, 377–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denzin, N.K.; Lincoln, Y.S. (Eds.) The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research, 5th ed.; Sage Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Woodfield, K.; Iphofen, R. Introduction to volume 2: The ethics of online research. In The Ethics of Online Research—Advances in Research Ethics and Integrity; Woodfield, K., Ed.; Emerald Publishing: Bingley, UK; Volume 2, pp. 1–12.

- The Testimonies Project. Available online: https://www.vaxtestimonies.org/ (accessed on 8 May 2023).

- Hoffmann, K.; Michalak, M.; Bonka, A.; Bryl, W.; Myslinski, W.; Kostrzewska, M.; Kopciuch, D.; Zaprutko, T.; Ratajczak, P.; Nowakowska, E.; et al. Association between Compliance with COVID-19 Restrictions and the Risk of SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Poland. Healthcare 2023, 11, 914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Ji, Y.; Sun, X. The impact of vaccine hesitation on the intentions to get COVID-19 vaccines: The use of the health belief model and the theory of planned behavior model. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 882909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.B.; Alam, M.Z.; Islam, M.S.; Sultan, S.; Faysal, M.M.; Rima, S.; Mamun, A. Health belief model, theory of planned behavior, or psychological antecedents: What predicts COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy better among the Bangladeshi adults? Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 711066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallucca, A.; Immordino, P.; Riggio, L.; Casuccio, A.; Vitale, F.; Restivo, V. Acceptability of HPV Vaccination in Young Students by Exploring Health Belief Model and Health Literacy. Vaccines 2022, 10, 998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teitler-Regev, S.; Hon-Snir, S. Focus: Vaccines: COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in Israel immediately before the vaccine operation. Yale J. Biol. Med. 2022, 95, 199. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Inchi, L.; Rottman, A.; Zarecki, C. “The Right to Our Own Body Is Over”: Justifications of COVID-19 Vaccine Opponents on Israeli Social Media. COVID 2024, 4, 1012-1025. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid4070070

Inchi L, Rottman A, Zarecki C. “The Right to Our Own Body Is Over”: Justifications of COVID-19 Vaccine Opponents on Israeli Social Media. COVID. 2024; 4(7):1012-1025. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid4070070

Chicago/Turabian StyleInchi, Liron, Amit Rottman, and Chen Zarecki. 2024. "“The Right to Our Own Body Is Over”: Justifications of COVID-19 Vaccine Opponents on Israeli Social Media" COVID 4, no. 7: 1012-1025. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid4070070

APA StyleInchi, L., Rottman, A., & Zarecki, C. (2024). “The Right to Our Own Body Is Over”: Justifications of COVID-19 Vaccine Opponents on Israeli Social Media. COVID, 4(7), 1012-1025. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid4070070