A Social Determinants Perspective on Adolescent Mental Health during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Purpose and Research Questions

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

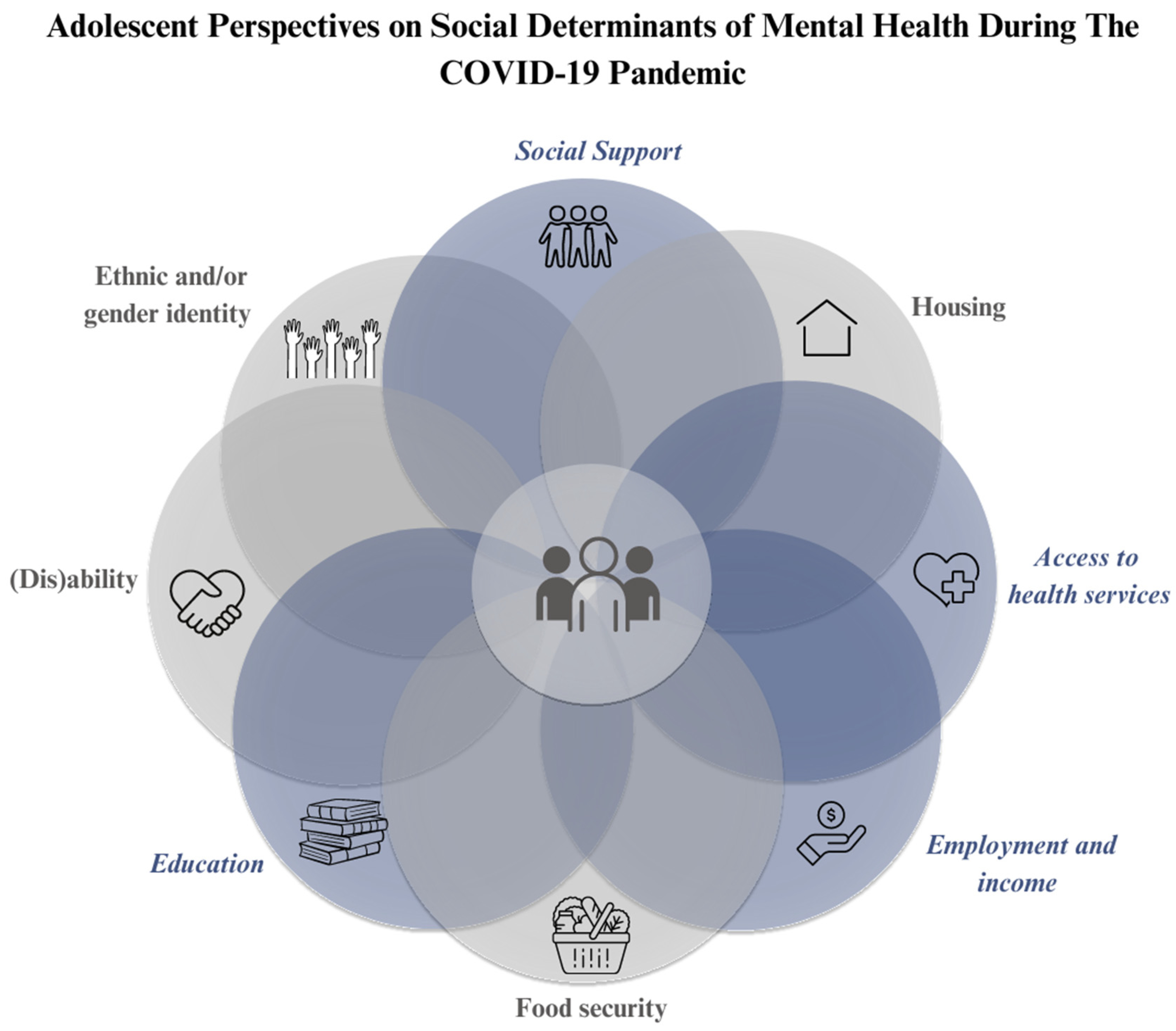

2.2. SDoH Framework

2.3. Sampling and Recruitment

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Participant Characteristics

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Findings

3.1. Education: “The One That Hit the Hardest”

3.2. Access to Health Services: “Everything Was Shut Down”

Such experiences of inability to access needed health services were upsetting for some participants, calling into question perceptions of basic rights to care. Reflecting on his experience, Steven (age 19, Edmonton) added, “it was terrible, [everything] was shut down … I was thinking that this is not the Canada that I would choose or that I’d want to choose. So it really affected me in a very big way”.I couldn’t get the normal medical routine I used to … I was trying to get treatment, [but] everywhere was shut down. So I couldn’t get the treatment I was supposed to get. The injury started getting serious because everywhere was locked down.(Steven, age 19, Edmonton)

For Amanda, long wait times to receive mental health support during the pandemic, coupled with the transition to online or virtual delivery of mental health services, made it even more difficult to access mental health services.At that time there wasn’t always the resources to help you … because everything was shut down. Even if you did [access mental health services], it’d be so long to wait to talk to someone. And things were always virtual which I didn’t, I don’t necessarily love. At the time I hated it.(Amanda, age 18, Grove County)

3.3. Employment and Income: “How Am I Going to Cope with My Basic Needs?”

Now that my mom is at home [unemployed], we don’t have really enough [financial] resources to stay online all the time. So sometimes when I’ll miss my classes, that will make me feel so sad because when I’m trying to read it on my own, I don’t really understand. Just feeling like this is now the end of me, like I don’t have any friends to ask the questions.(Mary, age 18, Edmonton)

Melissa (age 18, Edmonton) primarily attributed income insecurity during the pandemic to her diminished mental wellness: “My main difficulty was my financial help. How will I be financially capable of taking care of my needs? That really had a negative impact on me and I wasn’t stable for the early few months of the pandemic”. The lack of financial security that accompanied PHMs for Melissa introduced additional worry, with mental health impacts.When I heard that my work was canceled and I wasn’t going to work, I was like, “How am I going to cope with my basic needs or providing for myself?” … I was just shattered. How am I going to do financially? Because this was the main source of my income. How am I going to compensate?(Melissa, age 18, Edmonton)

Although most adolescents experienced stress and worry as workplaces closed and income insecurity increased, the PHMs also contributed to greater financial stability for others as their schedules became more flexible. Changes to employment and income, including for adolescents and their families, subsequently affected some participants’ educational experiences and social support as well, with mental health consequences.I felt really blessed to be able to go from a 15-h workweek to like 30 h a week, so I was able to make more money than what I was before … Not only was I available to work more, I could manage school and work at the same time.(Kyle, age 18, Grove County)

3.4. Social Support: “I Almost Lost My Mind”

For Ava, social isolation began to breed more social isolation, compounding the mental health difficulties they encountered during the pandemic.I started [to] not enjoy talking to people. Before Covid hit, I really loved talking to people … But once I got that separation, it just became hard to even consider planning socially distanced meetups. I just didn’t want to go through the trouble of it, it just wasn’t worth going out there. I just lost my social connection, and not having that really hurt my mental health.(Ava, age 16, Grove County)

When Cory (age 16, Grove County) experienced the death of a close friend during the pandemic, separation from his peers only magnified the negative effect on his mental health. In becoming disconnected from their friends and peers, participants expressed that they had lost a significant aspect of their social support networks.Before Covid, if I had [something] eating me up, I could just talk it over with someone. I used to rather talk [about] it with someone one on one. During [the pandemic] and all those restrictions that came with it, people that I interacted with [were] just my family members, and those things I can’t talk [about] with my family.(Reggie, age 18, Edmonton)

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications and Areas for Further Study

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Viner, R.M.; Ozer, E.M.; Denny, S.; Marmot, M.; Resnick, M.; Fatusi, A.; Currie, C. Adolescence and the social determinants of health. Lancet 2012, 379, 1641–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.; Loureiro, A.; Cardoso, G. Social determinants of mental health: A review of the evidence. Eur. Psychiatry 2016, 30, 259–292. [Google Scholar]

- Compton, M.T.; Shim, R.S. The social determinants of mental health. FOC 2015, 13, 419–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Risks to Mental Health: An Overview of Vulnerabilities and Risk Factors. Background Paper by WHO Secretariat for the Development of a Comprehensive Mental Health Action Plan. Geneva: World Health Organization. Published 16 October 2012. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/risks-to-mental-health (accessed on 17 June 2023).

- Kessler, R.C.; Berglund, P.; Demler, O.; Jin, R.; Merikangas, K.R.; Walters, E.E. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of dsm-iv disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2005, 62, 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearson, C.; Janz, T.; Ali, J. Mental and Substance Use Disorders in Canada. Statistics Canada. Published 2013. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/82-624-x/2013001/article/11855-eng.pdf (accessed on 15 August 2023).

- Taylor, B.K.; Fung, M.H.; Frenzel, M.R.; Johnson, H.J.; Willett, M.P.; Badura-Brack, A.S.; White, S.F.; Wilson, T.W. Increases in circulating cortisol during the COVID-19 pandemic are associated with changes in perceived positive and negative affect among adolescents. Res. Child Adolesc. Psychopathol. 2022, 50, 1543–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fung, M.H.; Taylor, B.K.; Embury, C.M.; Spooner, R.K.; Johnson, H.J.; Willett, M.P.; Frenzel, M.R.; Badura-Brack, A.S.; White, S.F.; Wilson, T.W. Cortisol changes in healthy children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic. Stress 2022, 25, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, S.E.; Best, J.; Selles, R.; Naqqash, Z.; Lin, B.; Lu, C.; Au, A.; Snell, G.; Westwell-Roper, C.; Vallani, T.; et al. Age-specific determinants of psychiatric outcomes after the first COVID-19 wave: Baseline findings from a Canadian online cohort study. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2023, 17, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canadian Institute for Health Information. Canadian COVID-19 Intervention Timeline. Published 13 October 2022. Available online: https://www.cihi.ca/en/canadian-covid-19-intervention-timeline (accessed on 23 July 2023).

- Birkeland, M.S.; Torsheim, T.; Wold, B. A longitudinal study of the relationship between leisure-time physical activity and depressed mood among adolescents. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2009, 10, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adedeji, A.; Otto, C.; Kaman, A.; Reiss, F.; Devine, J.; Ravens-Sieberer, U. Peer relationships and depressive symptoms among adolescents: Results from the german bella study. Front. Psychol. 2022, 12, 767922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, M.; Joshi, A. The Influence of Peer Relationships in the Middle Years on Mental Health. Australian Government Australian Institute of Family Studies. Published February 2024. Available online: https://aifs.gov.au/sites/default/files/2024-02/2402-Middle-Years-CFCA-Paper.pdf (accessed on 14 August 2024).

- Nwachukwu, I.; Nkire, N.; Shalaby, R.; Hrabok, M.; Vuong, W.; Gusnowski, A.; Surood, S.; Urichuk, L.; Greenshaw, A.J.; Agyapong, V.I.O. COVID-19 Pandemic: Age-Related Differences in Measures of Stress, Anxiety and Depression in Canada. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prichett, L.M.; Yolken, R.H.; Severance, E.G.; Carmichael, D.; Zeng, Y.; Lu, Y.; Young, A.S.; Kumra, T. COVID-19 and youth mental health disparities: Intersectional trends in depression, anxiety and suicide risk-related diagnoses. Acad. Pediatr. 2024, 24, 837–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawke, L.D.; Barbic, S.P.; Voineskos, A.; Szatmari, P.; Cleverley, K.; Hayes, E.; Relihan, J.; Daley, M.; Courtney, D.; Cheung, A.; et al. Impacts of COVID-19 on Youth Mental Health, Substance Use, and Well-being: A Rapid Survey of Clinical and Community Samples: Répercussions de la COVID-19 sur la santé mentale, l’utilisation de substances et le bien-être des adolescents: Un sondage rapide d’échantillons cliniques et communautaires. Can. J. Psychiatry 2020, 65, 701–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeung, C.Y.; Men, V.Y.; So, W.W.Y.; Fong, D.Y.T.; Lam, M.W.C.; Cheung, D.Y.T.; Yip, P.S.F. Risk and protective factors related to changes in mental health among adolescents since COVID-19 in Hong Kong: A cross-sectional study. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2023, 17, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beames, J.R.; Li, S.H.; Newby, J.M.; Maston, K.; Christensen, H.; Werner-Seidler, A. The upside: Coping and psychological resilience in Australian adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2021, 15, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ludwig-Walz, H.; Dannheim, I.; Pfadenhauer, L.M.; Fegert, J.M.; Bujard, M. Increase of depression among children and adolescents after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in Europe: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2022, 16, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meherali, S.; Punjani, N.; Louie-Poon, S.; Abdul Rahim, K.; Das, J.K.; Salam, R.A.; Lassi, Z.S. Mental health of children and adolescents amidst COVID-19 and past pandemics: A rapid systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montreuil, M.; Gendron-Cloutier, L.; Laberge-Perrault, E.; Piché, G.; Genest, C.; Rassy, J.; Malboeuf-Hurtubise, C.; Gilbert, E.; Bogossian, A.; Camden, C.; et al. Children and adolescents’ mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative study of their experiences. Child Adoles. Psych. Nurs. 2023, 36, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahk, Y.C.; Jung, D.; Choi, K.H. Social distancing policy and mental health during COVID-19 pandemic: An 18-month longitudinal cohort study in South Korea. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1256240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, V.; Dumont, R.; Lorthe, E.; Loizeau, A.; Baysson, H.; Zaballa, M.-E.; Pennacchio, F.; Barbe, R.P.; Posfay-Barbe, K.M.; Guessous, I.; et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on children and adolescents: Determinants and association with quality of life and mental health—A cross-sectional study. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2023, 17, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, H.M.; Runions, K.C.; Lester, L.; Lombardi, K.; Epstein, M.; Mandzufas, J.; Barrow, T.; Ang, S.; Leahy, A.; Mullane, M.; et al. Western Australian adolescent emotional wellbeing during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2022, 16, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardini, F.; Attademo, L.; Rotter, M.; Compton, M.T. Social determinants of mental health as mediators and moderators of the mental health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatr. Serv. 2021, 72, 598–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Y.; Yip, P.S.F.; Pathak, J.; Mann, J.J. Association of social determinants of health and vaccinations with child mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic in the us. JAMA Psychiatry 2022, 79, 610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duby, Z.; Bunce, B.; Fowler, C.; Bergh, K.; Jonas, K.; Dietrich, J.J.; Govindasamy, D.; Kuo, C.; Mathews, C. Intersections between COVID-19 and socio-economic mental health stressors in the lives of South African adolescent girls and young women. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2022, 16, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magson, N.R.; Freeman, J.Y.A.; Rapee, R.M.; Richardson, C.E.; Oar, E.L.; Fardouly, J. Risk and protective factors for prospective changes in adolescent mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Youth Adolesc. 2021, 50, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorne, S. Interpretive Description: Qualitative Research for Applied Practice, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hawke, L.D.; Relihan, J.; Miller, J.; McCann, E.; Rong, J.; Darnay, K.; Docherty, S.; Chaim, G.; Henderson, J.L. Engaging youth in research planning, design and execution: Practical recommendations for researchers. Health Expect. 2018, 21, 944–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boeije, H. A purposeful approach to the constant comparative method in the analysis of qualitative interviews. Qual. Quant. 2002, 36, 391–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wigger, E. The Whitehall Study. Unhealthy Work—The Center for Social Epidemiology. Classic Studies, Current Studies. Published 2011. Available online: https://unhealthywork.org/classic-studies/the-whitehall-study/ (accessed on 25 August 2023).

- Marmot, M.; Wilkinson, R. Social Determinants of Health; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Social Determinants of Health. Published 27 August 2008. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-IER-CSDH-08.1 (accessed on 8 July 2023).

- Government of Canada. Social Determinants of Health and Health Inequalities. Published 1 June 2023. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/health-promotion/population-health/what-determines-health.html (accessed on 25 August 2023).

- Canadian Mental Health Association [CMHA]. Social Determinants of Health. Published 2023. Available online: https://ontario.cmha.ca/provincial-policy/social-determinants/ (accessed on 22 June 2023).

- Bhardwaj, P. Types of sampling in research. J. Prim. Care Spec. 2019, 5, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Thielke, R.; Payne, J.; Gonzalez, N.; Conde, J.G. Research electronic data capture (Redcap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J. Biomed. Inform. 2009, 42, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayan, M.J. Essentials of Qualitative Inquiry, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Zoom Support. Audio Transcription for Cloud Recordings. Published 13 October 2022. Available online: https://support.zoom.us/hc/en-us/articles/115004794983-Audio-transcription-for-cloud-recordings (accessed on 2 August 2023).

- Canadian Mental Health Association [CMHA]. Mental Health Promotion in Ontario: A Call to Action. Published November 2008. Available online: https://ontario.cmha.ca/documents/mental-health-promotion-in-ontario-a-call-to-action/ (accessed on 12 August 2023).

- de Oliveira, W.A.; da Silva, J.L.; Andrade, A.L.M.; Micheli, D.D.; Carlos, D.M.; Silva, M.A.I. Adolescents’ health in times of COVID-19: A scoping review. Cad. Saúde Pública 2020, 36, e00150020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cost, K.T.; Crosbie, J.; Anagnostou, E.; Birken, C.S.; Charach, A.; Monga, S.; Kelley, E.; Nicolson, R.; Maguire, J.L.; Burton, C.L.; et al. Mostly worse, occasionally better: Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of Canadian children and adolescents. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2022, 31, 671–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawel, A.; Shou, Y.; Smithson, M.; Cherbuin, N.; Banfield, M.; Calear, A.L.; Farrer, L.M.; Gray, D.; Gulliver, A.; Housen, T.; et al. The effect of COVID-19 on mental health and wellbeing in a representative sample of Australian adults. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 579985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kourgiantakis, T.; Markoulakis, R.; Hussain, A.; Lee, E.; Ashcroft, R.; Williams, C.; Lau, C.; Goldstein, A.L.; Kodeeswaran, S.; Levitt, A. Navigating inequities in the delivery of youth mental health care during the COVID-19 pandemic: Perspectives of youth, families, and service providers. Can. J. Public Health 2022, 113, 806–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ligus, K.; Fritzson, E.; Hennessy, E.A.; Acabchuk, R.L.; Bellizzi, K. Disruptions in the management and care of university students with preexisting mental health conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic. Transl. Behav. Med. 2021, 11, 802–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canadian Mental Health Association. Mental Health at the Pandemic’s End: Youth Still Reporting Higher Rates of Mental Health Problems. Published December 2023. Available online: https://cmha.ca/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/CMHA-YouthMHRC-Final-ENG.pdf (accessed on 16 August 2024).

- Taylor, M.; Dimitropoulos, G.; Scott, S.D.; Ben-David, S.; Hilario, C. ‘The walls had been built’: A qualitative study of Canadian adolescent perspectives on mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Glob. Qual. Nurs. Res. 2024, 11, 23333936241273270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canadian Institute for Health Information. Canadians Report Increasing Need for Mental Health Care Alongside Barriers to Access. Published 21 March 2024. Available online: https://www.cihi.ca/en/canadians-report-increasing-need-for-mental-health-care-alongside-barriers-to-access (accessed on 16 August 2024).

- Hu, T.; Zhang, D.; Wang, J. A meta-analysis of the trait resilience and mental health. Pers. Individ Dffer. 2015, 76, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Zhao, L.; Liu, M.; Hong, B.; Jiang, L.; Jia, P. Resilience and mental health: A longitudinal cohort study of Chinese adolescents before and during COVID-19. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 948036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauschenberg, C.; Schick, A.; Goetzl, C.; Roehr, S.; Riedel-Heller, S.G.; Koppe, G.; Durstewitz, D.; Krumm, S.; Reininghaus, U. Social isolation, mental health, and use of digital interventions in youth during the COVID-19 pandemic: A nationally representative survey. Eur. Psychiatry 2021, 64, e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskin, T.W.; Wampold, B.E.; Quintana, S.M.; Enright, R.D. Belongingness as a protective factor against loneliness and potential depression in a multicultural middle school. Couns. Psychol. 2010, 38, 626–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiansen, J.; Qualter, P.; Friis, K.; Pedersen, S.; Lund, R.; Andersen, C.; Bekker-Jeppesen, M.; Lasgaard, M. Associations of loneliness and social isolation with physical and mental health among adolescents and young adults. Perspect. Public Health 2021, 141, 226–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loades, M.E.; Chatburn, E.; Higson-Sweeney, N.; Reynolds, S.; Shafran, R.; Brigden, A.; Linney, C.; McManus, M.N.; Borwick, C.; Crawley, E. Rapid systematic review: The impact of social isolation and loneliness on the mental health of children and adolescents in the context of COVID-19. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2020, 59, 1218–1239.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballonoff, S.A.; Till, H.L.; Cohen, A.K. “It was definitely like an altered social scene”: Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic restrictions on U.S. adolescents’ social relationships. Youth 2023, 3, 18–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Harris, K.M. Association of positive family relationships with mental health trajectories from adolescence to midlife. JAMA Pediatr. 2019, 173, e193336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samji, H.; Wu, J.; Ladak, A.; Vossen, C.; Stewart, E.; Dove, N.; Long, D.; Snell, G. Review: Mental health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on children and youth—A systematic review. Child Adoles. Ment. Health 2022, 27, 173–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frew, N. Alberta Lifting Almost all Remaining COVID-19 Restrictions March 1. Canadian Broadcasting Corporation News. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/Edmonton/alberta-covid-19-step-2-restrictions-lifted-1.6365902 (accessed on 26 February 2022).

- Galdas, P. Revisiting bias in qualitative research: Reflections on its relationship with funding and impact. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2017, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographic Categories | N (33) | Percentage (100%) |

|---|---|---|

| Residence during pandemic | ||

| Grove County | 16 | 48.5 |

| Edmonton | 17 | 51.5 |

| Gender identity at time of interview | ||

| Identify as a young woman | 18 | 54.5 |

| Identify as a young man | 12 | 36.4 |

| Identify as other | 2 | 6.1 |

| Undisclosed | 1 | 3.0 |

| Age at time of interview | ||

| 14 | 1 | 3.0 |

| 15 | 2 | 6.1 |

| 16 | 5 | 15.15 |

| 17 | 5 | 15.15 |

| 18 | 12 | 36.4 |

| 19 | 8 | 24.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Taylor, M.; Hilario, C.T.; Ben-David, S.; Dimitropoulos, G. A Social Determinants Perspective on Adolescent Mental Health during the COVID-19 Pandemic. COVID 2024, 4, 1561-1577. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid4100108

Taylor M, Hilario CT, Ben-David S, Dimitropoulos G. A Social Determinants Perspective on Adolescent Mental Health during the COVID-19 Pandemic. COVID. 2024; 4(10):1561-1577. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid4100108

Chicago/Turabian StyleTaylor, Mischa, Carla T. Hilario, Shelly Ben-David, and Gina Dimitropoulos. 2024. "A Social Determinants Perspective on Adolescent Mental Health during the COVID-19 Pandemic" COVID 4, no. 10: 1561-1577. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid4100108

APA StyleTaylor, M., Hilario, C. T., Ben-David, S., & Dimitropoulos, G. (2024). A Social Determinants Perspective on Adolescent Mental Health during the COVID-19 Pandemic. COVID, 4(10), 1561-1577. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid4100108