1. Introduction

The emergence of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in late 2019 transformed our world [

1]. Neither individuals nor institutions were immune, including higher education, as the COVID-19 pandemic precipitated two main changes; limitations on the size of social gatherings (accelerating a move to remote online learning), and public health mandates to reduce the spread of the virus (forcing everyone to retreat to their households or isolation bubbles) [

1]. Emergency remote teaching was characterized by “teaching with technology” and a “retreat to the household” where suddenly the household became the “remote” location of study, with technology as the means of instructional delivery [

2]. Dhawan [

3] reports that most higher education institutions had little pre-existing capacity for fully online instruction, with few able to transition their courses into anything remotely akin to pre-pandemic teaching and learning. A further complication beyond institutional capacity was the threat of an unseen, freely circulating airborne virus, contractable in proximity to others. The retreat to home bubbles helped to mitigate this omnipresent threat; however, the sudden shift to remote online learning was not conducive to creating an optimal teaching and learning environment. Guppy et al. [

1] report that the range of immediate challenges within student households had the greatest impact on their learning confidence, although there was some evidence of a digital divide, that is, with not all students having access to the technology and internet access they required.

Our contributions come from asking broad interrelated questions, designed to explore the extent to which the disruption of lifestyle (displacement), active lives (physical activity), learning (remote online platforms), and livelihood (employment) impacted Bachelor of Sport and Recreation (BSR) undergraduate students in New Zealand.

Research Questions:

How did the move to their home bubble impact student lifestyle (displacement), active lives (physical activity), learning (remote online learning), and livelihood (employment) during COVID-19 lockdown periods in 2020 and 2021?

What impact did the sudden change in pedagogical practice (from face-to-face to remote online) have on higher education students’ perceptions about their systems engagement, student–staff–student communication, access to technology, confidence with online platforms, motivation, and time management?

For student health and wellbeing, were factors outside their control (socio-ecological threat of catching the virus, social distancing, mandated vaccination, restricted gatherings, isolation rules, media coverage, loss of employment, government subsidies, etc.) more influential than the challenges they encountered through forced isolation in their home bubble?

As Sport and Recreation undergraduate students, what impact did the shift to online learning and restricted people contact have on their view of their ability to achieve their sporting, academic, and personal goals?

In 2020, in response to the coronavirus (delta) pandemic, New Zealand’s Ministry of Health [

4] imposed a four-level restrictions mandate, with a full lockdown at level four (25 March–27 April), followed by lesser restrictions at level three, including isolation periods and vaccination mandates (27 April–11 May, 12–30 August). All citizens were affected by approximately 10 weeks of lockdown restrictions. In 2021, level three restrictions were again imposed during February but reduced to level one (social distancing, mask wearing, high use of sanitation) from March until July. With the arrival of the COVID-19 omicron variant some months later, New Zealand returned to level four restrictions from 18 August to 22 September 2021 and then reduced to level three until a new red traffic light system (green, orange, and red) was in place [

4]. Restrictions under the red traffic light included QR scanning, showing vaccination passes, social distancing, restrictions on group numbers for social gatherings including funerals, weddings, and hospitality, isolation periods for self or family members testing positive for COVID-19, wearing a mask, off-site teaching and learning (all age groups), and limits on personal activities and travel.

During 2021, all citizens in New Zealand were restricted by severe (the Auckland region) to moderate (other regions) legislated restrictions for more than 16 weeks [

5]. Some services continued to operate during lockdown periods to ensure that essential services were available, such as supermarket shopping, health care, and public transport for essential workers [

5]. The initial move to ‘working and learning at home’ became a ‘new normal’ in which parents unexpectedly became home-school teachers, and teachers became virtual presenters and “guides” [

6]. In HE, this meant mandated online learning using existing IT platforms, as living by imposed levels and zones of restriction became a new way of life. Everyone’s lifestyle, livelihood, and active lives were impacted. However, school-aged children, secondary school youth, and university students had an additional layer of impact from the COVID-19 restrictions, namely, unprecedented disruption and changes to their learning experience [

7]. Students in HE experienced unprecedented changes in their daily routines and the mode of engagement with their learning environment. An emergency shift from traditional face-to-face learning to various online platforms from their “home bubbles” (the immediate family environment related to level 3 and 4 restrictions in New Zealand), is documented as contributing to students experiencing a decline in their general wellbeing [

8,

9].

To consider these impacts from an undergraduate student perspective, systems engagement, pedagogical approaches, and socio-ecological influences are examined (within and beyond the students’ isolation home bubble). To foreground a deeper examination of lockdown impacts, a summary of the COVID-19 events and main restrictions specific to the New Zealand context are included.

1.1. Systems Engagement during Lockdown Periods

The closure of schools and HE Institutions (HEIs) due to the coronavirus pandemic precipitated a sudden transition from campus-based, in-person learning to online learning from home (e-learning), locally and globally [

10,

11]. Much of the emerging literature suggests the transition has been overwhelming for students and lecturers alike as they navigated new and old online platforms, tools, and systems [

1,

3]. Moreover, a correlation between the quality of e-learning through IT systems and the timeliness of feedback from lecturers, with student satisfaction and performance, has been identified as a contributing factor in academic success [

12,

13].

When considering the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic from an undergraduate student perspective, studies indicate that although students have typically been satisfied with the transition to online due to factors such as the increase in freedom and flexibility (online schedules, flexibility with assessments, cancelled written exams), they also felt less engaged due to the lack of social interactions with their peers and lecturers [

13,

14,

15]. Other research relating to abrupt curriculum and policy changes during pandemic times reports profound impacts in all areas of life for students in HE, including increasing anxiety and mental health issues worldwide [

11,

16,

17,

18].

In New Zealand, to minimise the transmission of the virus, nationwide lockdowns of various durations and restrictions were enforced by the government. This meant national and international travel was limited, social and physical distancing measures were implemented, and mass gatherings such as students on campus were no longer permitted [

4,

19]. As a result, students in HE experienced unprecedented changes in their daily routines and the mode of engagement with their learning environment. An emergency shift from traditional face-to-face learning to various online platforms from their “home bubbles” is documented as contributing to students experiencing a decline in their general wellbeing [

8,

9]. Limited time outdoors to exercise or socialise during lockdown periods was found to exacerbate this trend [

10]. Collaborative research between Sport New Zealand and Wellington’s Victoria University [

20] highlights that as the country emerged from the first lockdown in June 2020, participation in weekly physical activity was significantly lower than before the pandemic. This longitudinal study across five data sets reported the trend continuing from June 2020 to April 2021, indicating a large and sustained decline in physical activity when compared to pre-pandemic.

To ascertain the benefits and barriers of this unexpected shift in systems engagement, access to student voice was viewed as essential. The decision to tap into the undergraduate student perspective on the COVID-19 restrictions and changes aimed to identify triggers for change in curriculum and policy from an undergraduate perspective. The purpose was to find ways to retain students during difficult times when many socio-ecological factors beyond their control impacted their daily lives, including their livelihood (employment), activity levels (personal space, physical activity, sport), and tertiary education (learning remotely). Creating and sustaining high-quality educational experiences, with and without unexpected disruptive events to teaching and learning, was a key driver for this research.

1.2. The Pedagogical Environment

The second area of background to this student voice research pertains to the pedagogical environment. Curriculum and policy reforms occurred at all levels of education, including innovations to accommodate lockdown restrictions, and, at a rapid pace, to create and deliver emergency remote learning opportunities. As of July 2020, 98.6% of learners worldwide were affected by the pandemic, representing 1.725 billion children and youth, from pre-primary to HE, in 200 countries [

21].

COVID-19 has reshaped the structure of teaching and learning in HE [

22]. The need for online learning was crucial during the lockdowns and is likely one way forward in the post-pandemic world. As a drastic change in teaching and learning, students, lecturers, educational institutions, and the government were faced with many new challenges, particularly relating to technology and educational policy. It is noted that professional development in teaching creativity and innovation will be beneficial to providing a supportive platform for students [

14]. Particularly in asynchronous settings, HE teachers must provide more opportunities for students to interact with each other and the teacher, not just on the learning content [

23]. Furthermore, students and teachers alike should be trained in the use of different online tools and platforms [

11]. This approach is viewed as influential to students’ engagement, academic performance, and well-being through their university years.

Typically, highly motivated students are relatively unaffected by online learning, as they do not require supervision for their studies, while students who face learning difficulties struggle more in the digital classroom, as they often require more support [

24]. Another challenge with online learning, particularly for students from low-income households, is the accessibility and affordability of internet/data packages and digital devices [

11,

25]. Lastly, increased screen time exposes students to potential exploitation and cyberbullying [

10]. These factors must be considered and actioned on through policy-level interventions so all students are given a fair opportunity to excel in their studies and are protected from potential online harm. Pandya and Lodha [

26] reported on the negative effect of prolonged screen time on health and mental health and showed that overuse of digital devices over time can be harmful. Hermassi et al. [

27] conducted a study in Qatar that confirmed that when physical activity and life satisfaction decreased for HE students, severe symptoms of anxiety and depression were evident.

Research by Bertrand et al. [

17] emphasised that university students are a vulnerable demographic group for inadequate physical activity levels. This view is supported by earlier research that acknowledged the effects of increased workload (assessments and employment) and limited time, low income, unsuitable weather, lack of motivation, and feeling tired [

28,

29] on the health and wellbeing of tertiary level students. More recently, Castro et al. [

30] reported that a considerable proportion of university students engaged in sedentary behaviour compared to similar-aged young adults and that an accumulation of sedentary time is associated with an increased risk of detrimental health outcomes. The sudden shift to remote online learning for HE students during the COVID-19 pandemic has created concern regarding health and physical activity behaviours during and post lockdown periods.

In New Zealand, the pedagogical environment available to tertiary students during the COVID-19 lockdowns aimed to deliver course content knowledge, to reshape and deliver appropriate assessment, and to provide pastoral support and care on an ‘as needs’ basis [

4,

31]. Some HEIs provided additional time extensions for the submission of written assessments to allow greater flexibility during uncertain times. To further accommodate student needs in some HEIs, an extra week was granted to all students who tested positive, or who were on COVID-19 home isolation for themselves and/or family members [

32]. Other institutions adjusted grades up by 5% to compensate [

33]. Managing this complex mix of remote online engagement and disengagement from their normal physical learning environment on campus created obstacles and opportunities for educators and students alike [

10]. For example, a recent editorial by Cowling et al. [

34] (p. 2) for the Journal of University Teaching and Learning Practice states that “in practical settings, teachers are frequently seeking out technology support from academic developers, educational designers, and technologists…” and that “the complexity of relationships between teaching and learning practices is increasing as we rethink higher education in the digital age, especially in the context of a global COVID-19 pandemic”. In an earlier study, Cowling and Birt [

35] highlighted the growing availability and capability of digital tools to enable educators to explore the process of teaching and learning in new ways, thus potentially changing the way we teach and learn. This shift, however, can lead academics to focus on the use of technology, instead of the adoption of technology tools to enhance teaching and learning experiences [

35]. Hybrid learning, where students choose whether to learn in person or to participate online [

36], is another option that needs consideration, especially in practical courses where ‘hands-on’ experience is essential.

Other pertinent literature relating to HE pedagogical environments during pandemic times include Väätäjä and Ruokamo’s [

37] work on the danger of putting technology first in teaching and learning in a way that compromises student learning experiences and Gurukkal’s [

38] study about using technology for teaching and learning beyond the simple operational use of the tool. For example, using Zoom or MS Teams to ‘broadcast’ content rather than using these tools to ‘teach’. Instead, the ideal online teaching and learning environment would perhaps be the use of Information and Communication Technology (ICT) tools that create peer/collaborative experiences (e.g., the use of breakout rooms or Padlet) or develop interaction/engagement (e.g., the use of chats or polls) within the lecture [

34].

Sport and Recreation HE students who generally prefer ‘embodied’ learning environments may be disadvantaged by learning remotely via digital platforms. A consideration of student learning preferences must be incorporated in policy-level interventions, so pedagogical practice aligns with student needs, especially during times of disruption. Research investigating students majoring in Physical and Health Education found that theoretical knowledge was generally unaffected; however, confidence to demonstrate and apply sports skills was low [

39]. Hence, developing effective HPE teachers requires the provision of practical ‘hands on’ experience to support confidence in ‘real’ teaching and learning situations.

The current study supplements other COVID-19 literature by providing a more comprehensive view of the impacts on Sport and Recreation undergraduate students in New Zealand during the 2020 and 2021 COVID-19 lockdowns.

1.3. Socio-Ecological Influences

COVID-19 lockdown measures, enforced by governments worldwide, affected human behaviour and lifestyles drastically. This consideration, based on socio-ecological influences, includes areas of significant impact such as dietary intake, sleep, stress, social connectedness, and the use of substances such as alcohol and tobacco [

9,

40,

41]. One major area was the effect that the closure of entertainment businesses and other organisations had on the emotional well-being and social connectedness of those in lockdown. These closures led to feelings of social isolation due to the restriction of movement in the community, which resulted in a reduction in social activity among family and friends [

42]. Luckily, with modern technology, most social connections were able to be somewhat maintained from a distance. Enari and Faleolo [

43] and Pandey et al. [

44] stated digital spaces, such as social media (Instagram and Facebook) and other online communication platforms (Messenger and Zoom), were used to connect with friends and family in separate family bubbles. This minimised the feelings of social isolation. The current literature also notes an increase in screen time and social media use during lockdown periods, particularly amongst young adults. Increased screen time was found to have a negative impact on how they viewed their quality of life and increased their anxiety [

16,

42,

44]. Furthermore, an increase in alcohol consumption and other harmful substances, an increase in sleep time, and a reduction in physical activity were also observed amongst young adults [

42,

45]. It is evident that the lifestyles of youth, students, and adults alike have been negatively impacted by the many restrictions generated by COVID-19 lockdowns.

Globally, a reduction in the physical activity levels of youth and students, and an increase in sitting time and sedentary behaviour have been observed [

17,

30,

46,

47]. This is due to home confinement, which provides limited space to exercise, limited exercise equipment, and restrictions on people being outdoors for long periods of time [

18]. It is also noted that the intensity of physical activity of students during COVID-19 decreased. Generally, those who were meeting recommended exercise guidelines during the COVID-19 lockdowns were also meeting the guidelines prior to the pandemic restrictions [

47,

48]. This was because higher classification student athletes had superior knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs regarding training, and better access to resources (space, equipment, facilities, support teams). In contrast, lower classification athletes, such as recreational athletes, found it more difficult to attain recommended physical activity levels due to compromised training prescriptions and periodisation [

48].

Recent research also indicates that the impact of COVID-19 has resulted in economic disruption, with tens of millions of people at risk of falling into extreme poverty, suffering a loss in income, complete job loss, and relocation from office spaces to “home bubbles” (except for essential workers) [

10,

49,

50,

51]. Those with low-income jobs and in more physical labour roles have been severely impacted by stress due to job loss and the fear of contracting the virus when looking for employment [

50]. Choi et al. also report that poorer, more vulnerable people who live day-by-day and have limited savings or resources will struggle to outlast the effects of the pandemic without support. As well as individuals, many businesses have suffered income loss, and many will face an existential threat [

52]. Luckily, many governments provided economic relief and aid for affected people and businesses by distributing food bags and cash allowances [

49,

50]. The New Zealand government’s COVID-19 Wage Subsidy provided financial support for employers and employees during the pandemic. This allowed affected and vulnerable families and businesses to live with less stress and financial pressure. However, the negative wellbeing impacts cannot be ignored, and even with financial assistance, many businesses are not expected to survive [

50,

52]. Again, students in practical-based study had to adapt equipment, provide video evidence of their work, and at times enlist family members to assist with tasks or assessments (coaching, science experiments, presentations).

While most studies have provided compelling evidence about the type of impact lockdowns have had on a population, Gerritsen et al., as cited in Roy et al. [

51], claimed that during the COVID-19 lockdowns in New Zealand, having limited access to fresh food (due to business closures and imposed social distancing) could have led to increased consumption of highly processed foods. In contrast, being forced to stay home may have created an opportunity to focus on food and diet and increased time for access to food-related advice online or from family and friends in order to continue eating a diet that supports good health [

52]. The literature from other parts of the world shows an increase in unhealthy eating habits, such as emotional snacking, overeating, or an increase in unhealthy food consumption [

42,

53,

54].

As mentioned earlier, student advocacy is a cornerstone of this study. Educator agency is also highlighted. Research by Priestley et al. [

55] conceptualised teacher agency and resilience, from a social-ecological perspective, as a multi-dimensional concept that is context- and role-specific, involving more than ‘bouncing back’ quickly and efficiently from adverse events. Previous research by Biesta and Tedder [

56] supported the notion that teacher agency, as a temporal and relational phenomenon, emerges during interaction within ecological circumstances. Viewed in this light, the achievement of agency during pandemic times can be understood as a configuration of influences from the past (the iterative dimension), orientations towards the future (the projective dimension), and engagement with the present (the practical-evaluative dimension) [

55].

Within the context of the COVID-19 lockdown restrictions, teacher resilience requires “equilibrium and a sense of commitment and agency in the everyday worlds in which teachers teach” [

57] (p. 26). From the social-ecological perspective, teacher resilience is environment-sensitive and process-oriented [

58].

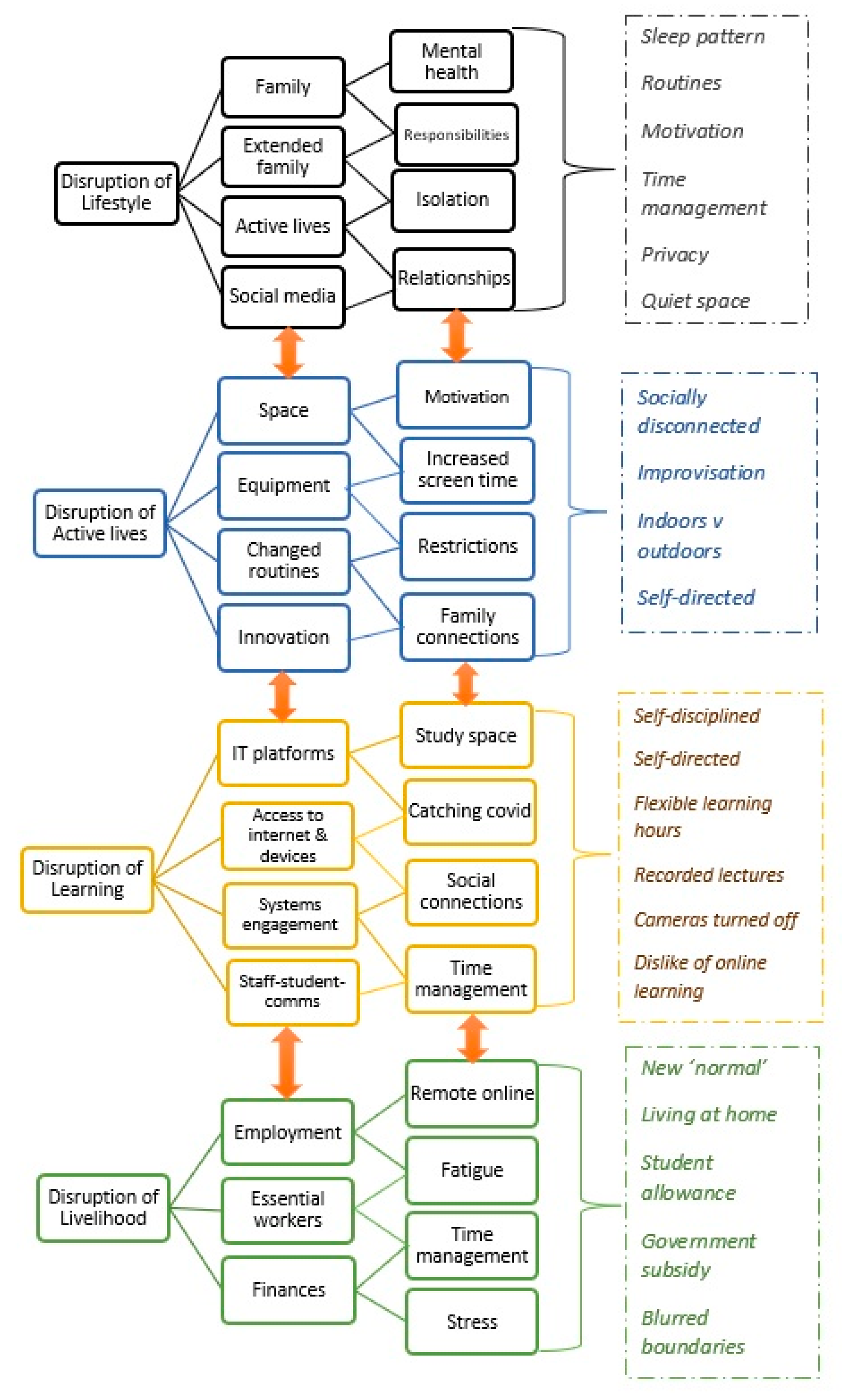

3. Findings

In New Zealand, HE students were also susceptible to the global and local impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. Rigorous data analysis and interpretation [

72,

73] revealed the main themes within the overarching theme of disruption (refer to

Figure 2), with sub-themes providing a further level of meaning regarding student perspectives relating to their lifestyle, active lives, learning, and livelihood. Shared experiences such as ‘changes to sleep pattern’, ‘flexible learning hours’, having ‘blurred boundaries’, and being ‘unable to be active except for a set time each day’ provide rich insights about the lived world of these Sport and Recreation undergraduate students during pandemic times.

Disruption due to the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic came in many forms. Lockdowns and various levels of restriction caused devastation across the globe, with the four pillars of lifestyle, livelihoods, academic learning, and active lives being abruptly changed for most people living in large cities and countries [

21]. Understandably, from 2020 to 2022 a plethora of research has surfaced regarding the global pandemic. The findings of this study, presented through the overarching themes of disruption of lifestyle, disruption of active lives, disruption of learning, and disruption of livelihood (

Figure 2), include examples of authentic student voice to provide ‘rich, thick description’ [

77] while incorporating contemporary research on the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, 2020–2022. The authors acknowledge that they did not investigate disruption to active lives to the same extent as student lifestyle, livelihood, and learning (refer to

Supplementary Materials); however, data from the semi-structured interviews and focus groups generated sufficient information to justify including the disruption to active lives theme in the findings and discussion sections.

3.1. Disruption of Lifestyle

The HE students in this study identified their abrupt change in lifestyle as “suddenly everyone was home. So, sort of that awareness of space sort of really changed within our house and within our home. It was quite a novelty to have everyone at home and to sort of have time, we had quite a lot of time to do stuff” (KG, second-year student). A mature first-year student (RB) said, “I think just being away from everyone, but then also just being stuck at home. You tend to just shy away from interactions with people, just because it’s a completely new environment, completely new, day to day kind of schedule”, whereas BF, a self-professed ‘doer’ stated, “lockdown happened, and it was strange. I didn’t know—I was sort of working before lockdown, had the break during lockdown where I didn’t really do anything, so I was just chilling out. And I didn’t know what to do. It was a weird thing”.

Undergraduate student responses revealed a sense of shock and feeling overwhelmed, but in some cases identified the benefits of a more flexible approach to their unprecedented change in lifestyle. MF, a mature third-year student, reflected that “I have like increased my screen time over lockdown. I used to go out, …, hanging out with friends playing football sometimes, … go to the beach but then as soon as you go into lockdown … that all like went away and I ended up doing a lot of stuff like watching YouTube. I used to be so shy about putting my camera on back then and I became a lot more confident and comfortable being on screen in a video call”.

For first-year BSR student JB it was a big change due to the fact that he was originally from Christchurch. He said, “it’s been my first year up in Auckland, so my lifestyle had already changed a little bit. And then, obviously COVID hit, and I was in the halls, and practically everyone left the halls when they had the chance. So, the village went from like 200 people to about 50”.

When asked whether their lifestyle was impacted more in the second rather than the first lockdown period, SF was clear that “Definitely the first one ... there’s so much uncertainty around it and then I have quite a lot of family in the UK. Practically all my extended family live in the UK so obviously that was quite stressful knowing that potentially they were going to get quite ill. The unknowns that came with the first lockdown. We had no idea like how long we were going to be in it for”. KG, a second-year student majoring in sports science and nutrition revealed: “Certainly the second one … sort of last August, last year in 2021. There was certainly a real fatigue of COVID information … just the uncertainty of it all, of not knowing what was happening”. This undergraduate student also noted the effect of media, government-mandated policies, and a change in the public response to the second lockdown. KG said “I sort of stopped watching the news, because it was just so intense all the time... the way the media reported it… there was so much fear… it was real doomsday and then, particularly in that second lot of lockdowns, people just started getting really angry”. “Having a mother hat on, I sort of really was conscious for my daughter, just to make sure to maintain a sense of hope. And that this is not going to be forever”.

3.2. Disruption of Active Lives

The students in this study reported sudden, significant changes to their activity routines, a loss of social connection from the cessation of sport and fitness pursuits, and for some, a general malaise due to increased screen time and restrictions on daily exercise outdoors. Others optimized the extra time at home to develop and improve their fitness. A third-year student, SF, whose normal lifestyle included surfing, kite surfing, and working part-time as a sailing coach, and who was close to completing her double degree in exercise science and sport management, commented:

When we were in level four lockdown the biggest thing for me was probably … I’m quite into my watersports, so don’t really normally spend more than a day not at the beach, with that being my workplace as well. I didn’t really get to go to the beach at all, especially in that initial lockdown for a good eight weeks, which is a huge change for me. (SF)

However, as a third-year student, SF was confident to apply her university knowledge to navigate and problem-solve the restrictions and limitations imposed on her. She stated “I think at that point I knew stuff that I could do to help me get through it like processes, so doing like lots of exercise I got pretty good, especially in the first lockdown… I got my 5 km, the fastest I have ever run. And so, I knew that going for runs and walks would be good”. This was not the case for two less experienced first-year students. RD reported “I think the biggest one was the ability to like to go to the gym, especially because I play rugby. So August, September, November would have been my offseason … I couldn’t train with others, which was tough especially because I like having time with others” while LH shared “I feel like having the ability to go to the gym regularly, or go to the pool for a swim, not just physically, but it helps reset your mental. And I feel like that was lacking throughout 2021, and especially in 2020”. Motivation was a key issue for JB, who in his first year in HE was a competitive pole vaulter. He revealed:

I had everything handed to me. I had a coach who was still giving me programs to do like, I’d still do sprints, I should have been doing sprint training and not weights, but body weight work. But yeah … it started off okay and then the couch and Netflix got really nice. And I just kind of depleted from there. (JB)

Our research tells us that the opportunity to continue training or be physically active was restricted.

3.3. Disruption of Learning—Teaching and Learning in a Different Way

Students stated that during their first and second lockdown periods, learning was compromised. There were delays from the university in moving to an online delivery model as highlighted by SF’s comments: “I found the first lockdown really hard because [my university] did that thing where rather than just bringing the holiday forward two weeks they ended up making it four weeks and then they kept changing how they were going to present the rest of uni. My sister’s uni went online pretty much right away… and my parents both worked full time, so again, their work went straight to being online. That meant that I didn’t really have much to do during the day, let alone anyone at home to interact with. So that made it pretty challenging in that first one.”

Engagement with students via announcements (Blackboard intranet portal) and emails was initially sparse, with unclear messages regarding the direction of future teaching and learning policies and procedures. A lack of communication caused confusion, misinformation, and delays that exacerbated the students’ experience as university-level learners. For example, first-year Bachelor of Sport and Recreation students had been on campus for barely four weeks when the call to lockdown was made. A further four-week delay occurred before online platforms and programmes commenced. This was a specific issue for the university in this study, while other New Zealand universities appeared to switch to online learning platforms seamlessly. However, many educational institutions worldwide had to organise ‘emergency’ adaptations to curriculum practice and policy implementation.

A sudden adjustment from face-to-face teaching and learning to remote online and later blended (asynchronous) learning models caused unprecedented disruption, and in some cases stalled student academic progress. JB, a first-year student, reported that he had issues with learning online. “This year didn’t go great for me. And a lot of my classes I didn’t actually pass. … And after the first semester finished, I was meant to get some help from people and I got like one session before, and then never really heard from them again”. Third-year student LH added: “There’s just something about the atmosphere of being around people and bouncing ideas off in person that you just can’t replicate online”. Both students, however, acknowledged the benefits of having access to video recordings of classes as a learning aid and for flexibility when managing multiple commitments. JB commented: “say there was a test or an exam, I could quickly bring the video up the night before. I’d just watch a few of the videos”. LH considered the benefits of an asynchronous approach: “If you can’t actually make those live sessions, you have to rely on the recorded sessions. Yeah, I think having both, having the facility of both makes it a lot easier. Because obviously with recorded sessions, you can rewind, you can play it on 1.25 if you’re covering the content pretty fast”.

Predominantly ‘embodied’ learners, Sport and Recreation undergraduate students expected and reveled in their weekly physically active workshops. The abrupt removal of this mode of learning (during COVID-19 lockdowns) impacted not only the students’ physical well-being but also their mood, sleep patterns, relationships with family and friends, motivation, eating habits, and mental health. For example, LH reflected on his restricted physical space and activity. “I think that … regardless of how much you do, like during lockdown, … there’s always going to be a deficit there. But you try to do as much as you can. Going for walks was a good chance for me to reset my mental… walking with my family. And so that was just nice—we’re all out of the house … away from everyone doing work”.

An unexpected outcome of the forced shift to online remote learning was an overemphasis on assessment completion and achievement [

8]. In the present study, educators and students experienced additional pressure to focus on assessments due to the limitations imposed by the available online platforms. For example, educators were advised to reduce their delivery time by half and to deliver bite-size chunks with a variety of activities and tools to engage and connect in a positive way with their students. Video Panopto recordings of course content knowledge were restricted to 15–20 min per video, up to a maximum delivery of 60 min, again accompanied by activities, video clips, and interactive surveys or polls to gain and hold student attention. Consequently, assessment completion and achievement became paramount as the teacher–student contact time was reduced substantially. Students identified a lack of opportunity to ask questions or engage in meaningful discussions with their peers and tutors while learning online.

“Like MD [focus group peer] I love studying and doing the work in a library. That sort of environment just helps me … so not having that kind of environment around me, made me a bit lacking in terms of getting work done” (LH). JB missed chatting to fellow students before and after classes.

While all research subjects confirmed that they had access to an electronic device for study, MD had to share with other family members and had intermittent Wi-Fi connectivity due to her location. SN struggled to find a comfortable quiet workspace, finally settling on a makeshift cardboard box ‘desk’ on her bed, mainly to ensure that her background was not identifiable when on video calls via Zoom or Microsoft Teams. SN’s sense of discomfort with her learning environment was described as “most often me and my flat mate would find the best way for us both to kind of study was to sit at the kitchen table, but when I had zoom meetings, they would be like two hours, so to then find a space where it was comfy to sit up for two hours was a little bit more challenging”.

Issues with mental wellbeing were reported by some HE students in this research. For example, JB recognised a decline in his mental state and in his ability to focus and complete his university work. He stated: “My mental side wasn’t great … I was never great at finishing work, like early, I was always reasonably on the later side of getting all my work done. And then that obviously got worse. And I got to the point where I was handing in work on the dot or just before and still not happy with it”. Conversely, LH explained: “I was surprisingly okay in terms of the mental side. I think it helped that I studied psychology beforehand” but LH revealed: “I was very conscious about, like, even going outside to do the grocery shopping just because my mom’s a nurse. She was actively involved with COVID cases and dealing with COVID patients coming in.”

Current research in this area [

14] highlights the dichotomy between online and campus-based teaching and learning with online deemed to be inferior to face-to-face delivery. Fabriz et al.’s [

23] work emphasizes teacher responsibility in asynchronous teaching to provide sufficient opportunities for students to interact with the content, the teacher, and other students. A synchronous teaching and learning approach, however, places responsibility on students to become more self-directed in their learning.

MF identified a benefit from the weeks of enforced online learning. MF noted “I have kind of developed on the technology side of me, you know, during lockdown to get to learn more about how to use different kinds of platform and social media”. On the other hand, RD reflected about how the online environment fluctuated in intensity, depending on the course, teacher, and students involved in the learning. RD said that “A lot of it was through zoom or through prerecorded classes … I’d have my camera on for the most part. I tried to interact, but sometimes it was just like, it was kind of weird. Sometimes we could do high interaction, sometimes it was pretty low”.

Student health and wellbeing became a main focus during the lockdown periods.

In this study, educators became the first point of contact to accommodate student needs. Regular teacher–student communication was designed to support students during challenging circumstances while also retaining them in their enrolled programmes. The student respondents confirmed the importance and effectiveness of teacher–student communication during lockdowns. “When I send out an email I get a reply within a day, which was handy. If not a couple of hours, which is good”. However, access to information and resources could break down when students did not attend classes (online). JB reported: “I didn’t actually finish the last assessment because I couldn’t find where the changes were to the actual assessment.” Most respondents reported that recorded classes and video explanations of processes and assessments were helpful to their learning. During COVID-19 lockdown periods, the remote online environment fundamentally challenged teachers to rethink their content and teaching in ways they were not prepared or educated for. This situation was exacerbated by practical and clinically-based disciplines, such as students in sport and recreation and the health sciences.

3.4. Disruption of Livelihood

The World Health Organisation [

49] released a statement confirming that tens of millions of people were at risk of falling into extreme poverty and that the threat to business enterprises worldwide would result in a high loss of employment across the global workforce. The recent literature generated from the impacts of the COVID-19 lockdowns and restrictions has begun to inform our understanding of the severity of these disruptions [

8,

16,

46], with students reporting that it “…almost hit me like a truck realizing that yeah, it’s gonna (sic) be hard” (MD first year student), while HE staff stated “My home bubble (lifestyle) revolved almost entirely around the demands and requirements of my employment (livelihood), with breaks for meals and occasional exercise. I recall thinking that the separation between home and work had become blurred, and it had” [

10].

In his first year of the Bachelor of Sport and Recreation programme, RB revealed: “in terms of work, obviously, everyone was affected in different ways. Some people were made redundant … and a lot of my family lost their jobs. And so, I’m having to pick up a lot more hours to actually scrape through each week. I was working 12-h shifts from the afternoon through to early morning. And then still having classes, in the early morning as well. That was probably the toughest part, just the time management and actually finding that balance.” RB also recognised the impact a sudden, unexpected change of livelihood could have: “so I guess the responsibility picked up … and [I had to] figure out how to still stay on top of studies. And just mentally stay sane, so to speak. It changed quite a bit mentally, just having to pick up a lot more responsibility within the household and things like that”. RD, a first-year student originally from Canada shared: ”I bartended for my rugby club. And when the lockdown happened everything was just cut, shut down. Um, we were paid subsidies throughout the lockdown, which was good”. Even when the lockdown restrictions began to ease, RD noted that the hospitality industry continued to have restricted capacity. He commented: “We went to a managed like capacity. We weren’t allowed to have the huge functions that we would have had back in June, so that meant all our hours got cut. I was working 20 h before and then it had dropped to eight or nine”. Other students also experienced sudden changes to their employment and level of responsibility within their home bubble. A third-year Samoan student JM shared: “my situation is a little bit different because I live with my grandmother so from the first lockdown, I didn’t have to really worry about her because she was … she was still plodding along. But then this year, she fell a little bit ill, so it became more responsibilities to try and balance uni and work and looking after my grandmother at the same time”.

Furthermore, what was once the personal space of many working adults had now also become their workspace [

10]. This blurred the line between workspace and personal space and between personal time and work time. KG, a second-year student and mother of two commented: “Luckily, for us, I was at that point in 2020, I was still working within a full-time role … A lot of my work I was able to do remotely. And the same with my partner, he was also able to work completely from home”. A first-year student, JB, had a different situation. Both parents were essential workers and so ‘at work’ each day, so he had one sibling learning remotely at home with him. JB recognised how anxious he was: “I think for me, it was just the anxiety… I was the designated person to stay home because my mom and dad were essential workers. And my brother got to do his stuff … but there was anxiety if I thought about going to the supermarket or an appointment or something like that. I might affect [infect] the family”. Contracting COVID-19, being in isolation, or transferring the disease to family members were the concerns most often cited. There had been a loss in social connections with fellow students, and an increase in workload, screen time, electronic mail, and notifications. This resulted in respondents feeling that they needed to be ‘working’ 24/7, which took a toll on the students’ overall mental health [

78]. Not knowing what the future will bring added another layer of anxiety to some students. “I was thinking about the future a little bit too much. I was thinking about the uncontrollables instead of the controllables. So yeah, that just kind of contributed to my anxiety a little bit” (JB). Conversely, MF, a mature third-year student reflected: “But before lockdown I used to think a lot about the future like what I want to do in 2022. Do I want to travel after I graduate? I really like to set plans for myself, because I’m very like, schedule oriented. But since lockdown, on the first lockdown, like I started to become more present if that makes sense. I started to worry less about the future and so on”, and “Just appreciating every single second and as it comes, because we never know what’s going to happen next year. So that was my lesson that I’ve learned as well”.

4. Discussion

The disruption of lifestyle, active lives, learning, and livelihood viewed from sport and recreation undergraduate student perspectives underpins this article. Hearing and responding to student voices about their experiences during pandemic times is essential for HE institutions to be agile, innovative, and appropriate when implementing ‘emergency’ adaptations to curriculum practice and policy in times of crisis. In this study, student voices highlight the need for timely, decisive action, and that is communicated clearly. Student voices highlight the need for greater awareness of their personal circumstances (lifestyle, livelihood, active lives) especially during unprecedented times, and student voices emphasise the impact exceptional circumstances had on their health and wellbeing. While the university in this study endeavoured to implement policies of pastoral care and support, it was the academic staff who provided day-to-day communication while also delivering course content through new ICT platforms. Discussion of triggers for change, reactions to restrictions, strategic measures, a socio-ecological approach, and the emergence of a ‘new normal’ from an undergraduate student perspective follows.

4.1. Triggers for Change

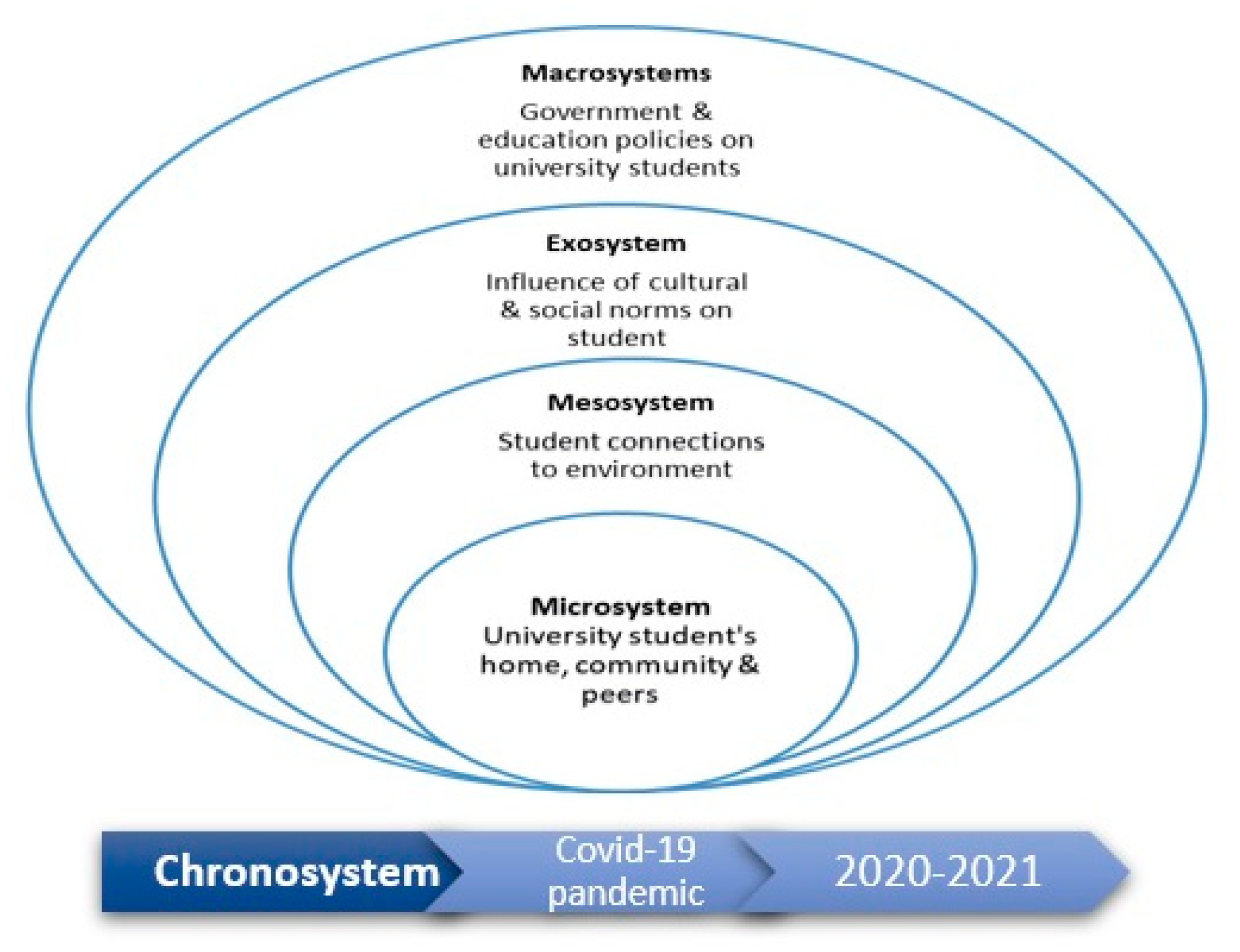

The COVID-19 pandemic and associated lockdown periods provided educators, policy-makers, community agencies, and individuals, in New Zealand and worldwide, with opportunities to reflect, act, and learn new ways of being and doing in unexpected and unprecedented times. Learning on multiple levels—micro, meso, exo, and macro [

67]—has occurred due to disruptions in lifestyle, active lives, learning, and livelihood, forcing individuals, families, communities, and nations to adapt quickly.

In response to the phenomenon of the COVID-19 restrictions imposed by the New Zealand government (2020–2022), curriculum and policy reforms and innovations became mandatory at all levels of education. The sudden, forced move to remote online digital platforms challenged educators, students, families, and policy-makers at the highest levels. Unprecedented times required unprecedented action. Insights from Cowling and Birt [

35] and Cowling et al. [

34] highlight teachers in practical settings (sport and recreation, clinical sciences) actively seeking technological support from academic developers, educational designers, and other technologies, in order to upskill and adapt their teaching practice as we rethink HE in the digital age. To maximise student engagement, wellbeing, and educational outcomes, students and teachers alike should be trained in the use of different online tools and platforms [

11].

Lalani et al.’s [

79] research warns that where educational theory is ignored in technology-enhanced learning and teaching, pedagogical practice also suffers. It is important to note, therefore, that in the rapid pivot to emergency remote teaching, much curriculum was digitized and transmitted via technology rather than transformed by it. Teaching and learning practices are increasingly under pressure because of increased academic workloads and the exigencies of emergency remote teaching, among other well-known pandemic pressures [

80]. It is tempting, therefore, to position technology implementations as solving educational problems. However, as Guppy et al. [

1] note, “people have agentic intentions, not technologies”. Developing new systems and designing discussion forums or social media networks do not enhance learning per se; such technology merely provides more channels of communication, whereby students already have access to increasingly sophisticated systems outside of the university. However, the need to have face-to-face contact with ‘others’ continues to be a key learning from this research. In the words of one first-year student:

Last year, during the other lockdown, it was completely different. There wasn’t too much interaction between lecturers and students in terms of that relational approach where they can actually feel comfortable enough to reach out and so when you don’t have that in person, heading online, you’re not even gonna [sic] try really? “This year I think the staff and faculty have been really supportive from the get-go. They kind of set the tone in terms of how open they were, and how supportive they were and how available they were, and so it was always easy to actually reach out because it became the norm when we were on campus. (First year student JB)

4.2. Reactions to Restrictions

Research by Bertrand et al. [

17], also in 2021, concluded that pandemic students experienced inadequate dairy intake, high alcohol consumption, low physical activity, and increased sedentary behaviour. Therefore, there are real concerns about the long-term effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on HE students. Additionally, university students are more likely to experience mental health issues than any other population [

81]. Moreover, there has been a decline in students’ mental health since the beginning of COVID-19 [

16,

78]. When LH recognised that his mood was changing, he decided to take action to counteract his sense of loneliness. “Recognizing that I was kind of heading down that [route] I pretty much after that first week I was like okay, I need to do something about this. So, I messaged a bunch of people like hey, on this day, can we have a call? Can we videocall? Is there any chance that I can -like can we just talk, just catch up and even if it’s like a 5–10-min call? And so that’s pretty much what I did throughout all of lockdown … just constantly seeing how other people are doing. And that kind of stopped that feeling of feeling lonely. And then it’s like okay, I’m alone, but I’m not lonely and that’s okay”.

In a time of social and health crisis, the importance of maintaining routine to remain healthy is paramount. There is a link between negative and harmful habits, such as increased screen time and consumption of unhealthy foods and mental health decline. MD, a first-year student and rowing coach reported: “For me, it was not being able to maintain a routine. It was a really big thing for me. It was probably like the worst thing”.

Additionally, it is clear to see that each of the lifestyle factors for young adults and students is influenced by one another, which highlights the importance of recognising unhealthy changes in behaviour and finding a balance during lockdowns. In this respect, first-year students reported more issues. For example, JB, as a first-year undergraduate majoring in coaching and nutrition stated: “I thought my adjustments were bad. Like I started going to sleep late and waking up later. And then class times would creep up and then still trying to keep on top of like fitness levels, trainings. It seemed to be the day finished quicker than I wanted it to. And I hadn’t got anything done uni wise”. Therefore, for a vulnerable group without well-consolidated habits, such as university students, additional emphasis and education should be placed on self-care, disease prevention, and healthy lifestyles [

18,

56].

4.3. Strategic Measures

Recent research shows that to combat potential health risks, university students should be targeted for interventions for improving their health and physical activity levels, particularly during uncertain and stressful periods such as lockdowns [

46,

80]. There are various ways in which students can be supported during this pandemic and beyond. For example, online aerobic and anaerobic exercise sessions hosted by a professional sports coach, with practical recommendations, new policies, and guidelines to encourage regular physical activity being released specifically for university students [

9,

47]. These measures can contribute to averting a public health crisis in the future. However, it is questioned whether there is a correlation between physical activity levels and mental health issues. Previously, it has been well-researched that physical activity is beneficial to mental health [

18,

20].

Although Rogowska et al. [

80] stated a weak link between physical activity levels and mental health in the context of COVID-19, there is sufficient evidence to show that a decrease in physical activity levels is indeed detrimental to students’ mental health. This is because exercise can reduce feelings of anxiety, depression, and other negative moods, which have commonly increased amongst the adult population during COVID-19. Consequently, exercise regimes should be implemented to improve cognitive functions and self-esteem, and, therefore, mental health [

46,

48,

79,

81]. In the context of this study, sport and recreation students reported the need to be regularly active with negative impacts on their wellbeing when exercise was substantially reduced during lockdown periods. The student respondents also supported the importance of the social interactions and connections associated with physical activity and sport, which were absent during COVID-19 restrictions.

4.4. A Socio-Ecological Approach

While the adapted model in

Figure 1 (p. 7) appears simplistic in design, the actions, reactions, and interactions between, across, and within each system are complex, that is, “open-ended, self-organising, adaptive forms constituted by many non-linear, dynamic interactions” [

68] (p. 73). Moreover, the experience of each undergraduate student is equally complex, individual, and unique even though they were exposed to the same COVID-19 lockdown regulations as other HE students.

Figure 3 provides a diagrammatic framework to encapsulate the complexity and possible extent of disruption, factors, influences, and consequences of the COVID-19-mandated restrictions.

When considering undergraduate student micro, meso, and exosystem (

Figure 3) impacts, the advocacy of each student’s lockdown experience is key to this research, as recognising student experience facilitates the identification of educational needs [

78]. With insights and knowledge, educators are better equipped to meet individual and collective needs by proactively accessing support and resources, informing educational policy, and adapting pedagogical practices to maximise learning during exceptional times. LH, a Tokelauan first-year student majoring in sport management explained that due to his cultural background and family support responsibilities he struggled with the blurred boundary between his university life and home life during lockdowns:

Family orientations do make it a lot harder. Because even if … you’re doing a module or something, cultural wise, if they ask you to do something, you do it, regardless of what you’re doing. And if you don’t do it, then it’s a whole lot of disrespect. This is culturally how I have to respond, so I think that makes it even harder. Because uni life is now home life and home life doesn’t change… It was kind of like getting into a routine. Like I wake up, make my Nan’s breakfast, and then clean the house (vacuum, washing and all that kind of stuff). I get all that stuff out of the way first, and then I’m freed to do whatever I had to do … with all the small petty stuff on the side. So yeah, just getting into a routine helped out a lot. (First year student LH)

There is mounting evidence of the negative impacts of COVID-19 on poorer socio-economic groups worldwide. This could be due to this population being the most vulnerable to the current situation and, therefore, the most change and support is likely to be needed here. The gap in the literature is understanding the effects of COVID-19 on the lifestyle, active lives, learning, and livelihood of undergraduate students and whether positive inputs, policies, and interventions can be applied to offset the negative effects of a pandemic. For example, many individuals and businesses will require support to return to their pre-pandemic livelihoods. Therefore, assistance provided by governments and mental health interventions need to be implemented to reduce the stress and anxiety caused by pressures from increased, decreased, or disrupted work conditions and employment.

When considering the chronosystem (

Figure 3) from an educational perspective, throughout the pandemic, educational technology (EdTech) was offered by educators and institutions to address challenges posed by emergency remote teaching (ERT). In ERT, the HE curriculum is digitalized through a process of rapidly uploading lessons, lectures, assessments, instructional materials, and learning activities that were once face-to-face [

34]. Such a pivot meant few staff and students were sufficiently prepared for a learning environment centred around technology. Zoom software reported monthly active users’ growth from 10 million daily users in December 2019 to 300 million in April 2020, a testament to this exponential growth in technology use during pandemic times. However, the HE sectors have conflicting views as to the permanency of the current digital-driven learning and teaching climate [

68,

69,

70]. Yet, Cowling et al. [

35] reiterate the importance of focusing on educational technology, stating that even if the digital climate changes again, it is important to provide guidance and training for the future.

4.5. Emergence of a ‘New Normal’

What are the new learnings? What are the takeaway messages? What is the ‘new normal’ as it has been dubbed? Is it where we are now? And how do we anticipate the ‘what next’? Our student voice research highlights the need for greater emphasis on system change in HE in order to be agile and adaptive as the educational landscape changes (sometimes irrevocably), while also acknowledging the importance of well-being—life/work/study balance, regular physical activity, social interactions. Learnings from this research are that educators and policy-makers can navigate the ‘new normal’ by:

- (1)

Listening to student wellbeing needs. By creating opportunities to gather student voices in a safe, collaborative manner, deep, meaningful insights can be gained. The inclusion of a third-year scholarship student as the interviewer was instrumental in creating this conducive environment.

- (2)

Improving holistic support. The sudden shift to remote online learning in response to the COVID-19 pandemic increased HE student screen time and social media use. Increased screen time was found to have a negative impact on how students viewed their quality of life and increased their anxiety, which are clear indicators that person-centred, individualised support is needed during exceptional times.

- (3)

Accommodating training and physical activity requirements. In courses and programmes requiring hands-on practical application of theoretical concepts, such as sports studies and clinical sciences, alternative provisions must be made to address the shortfall when embodied learning is significantly reduced by the digitization of the learning environment.

- (4)

Providing ‘social’ spaces for peer interactions. Undergraduate students identified a sense of isolation, social disconnect, and low motivation and engagement with online learning when their ‘normal’ lifestyle routines were disrupted. Post-pandemic strategies need to consider the ‘social’ elements that have been missed or undermined during the pandemic to address these undergraduate student concerns.

Educationally, we must embrace curriculum and policy reforms to ensure that:

- (5)

We can navigate zones of disruption. While the level of disruption was all-encompassing, our research indicates that educators managed to provide some level of educational practice, albeit with unfamiliar or limited resources. The variation in educational experience during the pandemic has highlighted the shortfalls in systems and resources that need to be addressed.

- (6)

We consider a hybrid system that combines face-to-face and online learning independently of location. The disruption of familiar and known ways of teaching and learning has provided opportunities to explore alternative pedagogies, to review and revise curriculum content, and to consider forms of blended or hybrid learning as viable options for the future.

- (7)

Learning design is seamless and caters for a range of disciplines, particularly practical/clinical/work-integrated learning. The special requirements of hands-on, embodied learning courses require rethinking how and where practice-based, situated learning is supported, during a crisis and post-pandemic. The removal of face-to-face interactions during the COVID-19 lockdowns accentuated the shortfall of a fully online learning environment for practical/clinical/work-integrated learning courses.

- (8)

Universities create learning systems that are agile, innovative, and future-focused. Blended learning, student-led or student-initiated novel approaches, and increased online learning resources and assessments are some examples of embracing the ‘new normal’ in HE [

80]. Online learning is expected to play a prominent role in post-COVID-19 education, offering opportunities and challenges. Challenges include institutional support and collaborations, the development and sharing of learning resources, guidelines for effective technology integration, and the use of virtual learning environments to promote student-centred learning.

This study focuses on sport and recreation undergraduate student perspectives during pandemic times. Future research will consider the ongoing and long-term implications of the COVID-19 lockdowns on undergraduate and post-graduate students and teaching staff.

5. Conclusions

The economic and social disruption of COVID-19 lockdowns has caused devastation across the globe. The four pillars of lifestyles, livelihoods, academic learning, and active lives of individuals have abruptly changed for many people living in large cities and countries. There were more negative impacts linked with each of the four pillars and some crossover of impacts between the pillars. This included a decline in mental health and overall, wellbeing due to a decrease in physical activity and an increase in unhealthy eating, combined with the increased digital screen time to maintain social connections and for online learning. The lifestyle factors for young adults and students were influenced by one another, which highlights the importance of recognising unhealthy changes in behaviour and finding a balance during unprecedented times.

A limitation of this qualitative hermeneutic study is that while it highlights the multi-layered effects of the COVID-19 pandemic from an undergraduate student perspective, only 16 of the 120-plus cohort of canvased students responded and contributed. While the sample of 16 is small, the shared experiences of KG, RB, BF, MF, JB, SF, RD, LH, MD, and SN correlate with other research that has been undertaken with university students during the COVID-19 pandemic, both in New Zealand and globally [

8,

9,

10,

11,

16,

17,

23,

24,

38,

43,

47], etc. The authors include

Supplementary Materials (indicative questions) to provide transparency regarding data collected about students’ active lives during lockdown periods, and present

Figure 2, with ‘active lives’ as an overarching theme. While the research and indicative interview questions did not specifically target the students’ active lives, the collected data revealed considerable disruption to undergraduate physical activity levels, routines, and benefits. Consequently, the disruption to students’ active lives is acknowledged and discussed in this paper. This research is a starting point to establish a dialogue with undergraduate students regarding their experiences in times of crisis; however, follow-on research is needed to gain insights regarding the ongoing and perhaps long-term effects of COVID-19.

Reimagining learning, curriculum, and support systems based on student voice regarding the disruption to their lifestyle, active lives, learning, and livelihood can and will help to create flexible, agile, future-focused curricula and policies, to better equip HE students to achieve their academic goals.