Long COVID-19 Symptoms among Recovered Teachers in Israel: A Mixed-Methods Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

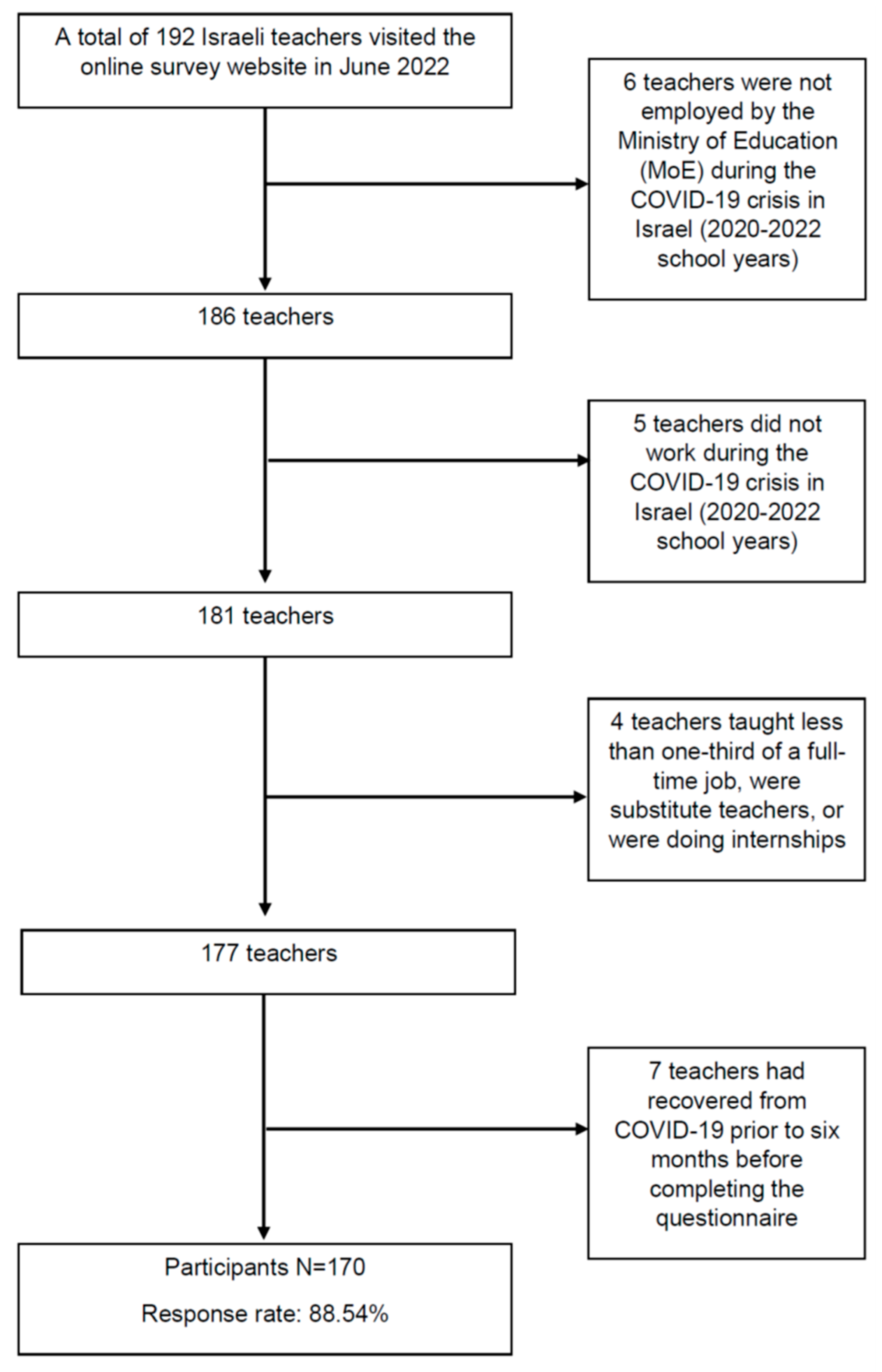

2.2. Sample

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Dependent Variables

2.3.2. Independent Variable

2.3.3. Qualitative Study

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Study

3.2. Qualitative Study

- (1)

- “I Am Neither Here nor There”

- (2)

- “I Try to Do Things Differently, but I don’t Succeed”

- (3)

- “Sometimes a Hug Can Help and Sometimes You Feel You’re Alone in the Battle”

4. Discussion

5. Practical Implications

6. Limitations

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yong, S.J. Long COVID or post-COVID-19 syndrome: Putative pathophysiology, risk factors, and treatments. Infect. Dis. 2021, 53, 737–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleischer, M.; Szepanowski, F.; Tovar, M.; Herchert, K.; Dinse, H.; Schweda, A.; Mausberg, A.K.; Holle-Lee, D.; Köhrmann, M.; Stögbauer, J.; et al. Post-COVID-19 syndrome is rarely associated with damage of the nervous system: Findings from a prospective observational cohort study in 171 patients. Neurol. Ther. 2022, 11, 1637–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Kessel, S.A.; Olde Hartman, T.C.; Lucassen, P.L.; van Jaarsveld, C.H. Post-acute and long-COVID-19 symptoms in patients with mild diseases: A systematic review. Fam. Pr. 2022, 39, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Proal, A.D.; VanElzakker, M.B. Long COVID or post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC): An overview of biological factors that may contribute to persistent symptoms. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayoubkhani, D.; Pawelek, P. Prevalence of Ongoing Symptoms Following Coronavirus (COVID-19) Infection in the UK: 1 July 2021. London: Office for National Statistics 2021. Available online: https://www.semiosis.at/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Prevalence-of-ongoing-symptoms-following-coronavirus-COVID-19-infection-in-the-UK-1-April-2021.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Davis, H.E.; Assaf, G.S.; McCorkell, L.; Wei, H.; Low, R.J.; Re’em, Y.; Redfield, S.; Austin, J.P.; Akrami, A. Characterizing long COVID in an international cohort: 7 months of symptoms and their impact. EClinicalMedicine 2021, 38, 101019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanichkachorn, G.; Newcomb, R.; Cowl, C.T.; Murad, M.H.; Breeher, L.; Miller, S.; Trenary, M.; Neveau, D.; Higgins, S. Post–COVID-19 syndrome (long haul syndrome): Description of a multidisciplinary clinic at Mayo Clinic and characteristics of the initial patient cohort. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2021, 96, 1782–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarei, M.; Bose, D.; Nouri-Vaskeh, M.; Tajiknia, V.; Zand, R.; Ghasemi, M. Long-term side effects and lingering symptoms post COVID-19 recovery. Rev. Med. Virol. 2022, 32, e2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carfì, A.; Bernabei, R.; Landi, F. Persistent symptoms in patients after acute COVID-19. JAMA 2020, 324, 603–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Q.; Zheng, B.; Daines, L.; Sheikh, A. Long-term sequelae of COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis of one-year follow-up studies on post-COVID symptoms. Pathogens 2022, 11, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrigues, E.; Janvier, P.; Kherabi, Y. Post-discharge persistent symptoms and health-related quality of life after hospitalization for COVID-19. J. Infect. 2020, 81, e4–e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Leon, S.; Wegman-Ostrosky, T.; Perelman, C.; Sepulveda, R.; Rebolledo, P.A.; Cuapio, A.; Villapol, S. More than 50 long-term effects of COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 16144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahyuhadi, J.; Efendi, F.; Al Farabi, M.J.; Harymawan, I.; Ariana, A.D.; Arifin, H.; Adnani, Q.E.S.; Levkovich, I. Association of stigma with mental health and quality of life among Indonesian COVID-19 survivors. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0264218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, L.; Islam, J.Y.; Mascareno, E.A.; Rivera, A.; Vidot, D.C.; Camacho-Rivera, M. Physical and Mental Health Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic among US Adults with Chronic Respiratory Conditions. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 3981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiyegbusi, O.L.; Hughes, S.E.; Turner, G.; Rivera, S.C.; McMullan, C.; Chandan, J.; Haroon, S.; Price, G.; Davies, E.H.; Nirantharakumar, K.; et al. Symptoms, complications and management of long COVID: A review. J. R. Soc. Med. 2021, 114, 428–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Havervall, S.; Rosell, A.; Phillipson, M.; Mangsbo, S.M.; Nilsson, P.; Hober, S.; Thålin, C. Symptoms and functional impairment assessed 8 months after mild COVID-19 among health care workers. JAMA 2021, 325, 2015–2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landsman, J.A.; Verheij, N.P.; Alma, M.A.; Boogaard, J.V.D.; Luning-Koster, M.; Evenboer, K.E.; Mei, V.D.; Reijneveld, S.A. COVID-19: Recovering at home is not easy. Ned. Tijdschr. Geneeskd. 2020, 164, D5358. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, P.; Proesmans, K.; Van, C.D.V.; Demarest, S.; Drieskens, S.; Pauw, R.D.; Cornelissen, L.; Ridder, K.D.; Charafeddine, R. Post COVID-19 condition and its physical, mental and social implications: Protocol of a 2-year longitudinal cohort study in the Belgian adult population. Arch. Public. Health 2022, 80, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lunt, J.; Hemming, S.; Elander, J.; Baraniak, A.; Burton, K.; Ellington, D. Experiences of workers with post-COVID-19 symptoms can signpost suitable workplace accommodations. Int. J. Workplace Health Manag. 2022, 15, 359–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, J.P.; Chesney, E.; Oliver, D.; Pollak, T.A.; McGuire, P.; Fusar-Poli, P.; Zandi, M.S.; Lewis, P.G.; David, P.A.S. Psychiatric and neuropsychiatric presentations associated with severe coronavirus infections: A systematic review and meta-analysis with comparison to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, 611–627. [Google Scholar]

- Fazel, M.; Hoagwood, K.; Stephan, S.; Ford, T. Mental health interventions in schools in high-income countries. Lancet Psychiatry 2014, 1, 377–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pressley, T. Returning to teaching during COVID-19: An empirical study on elementary teachers’ self-efficacy. Psychol. Sch. 2021, 58, 1611–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pressley, T.; Ha, C.; Learn, E. Teacher stress and anxiety during COVID-19: An empirical study. Sch. Psychol. 2021, 36, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levkovich, I.; Shinan-Altman, S.; Pressley, T. Challenges to Israeli Teachers during the Fifth Wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic: How Did They Cope When the Schools Reopened? Teach Educ. 2023, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tri Sakti, A.M.; Mohd Ajis, S.Z.; Azlan, A.A.; Kim, H.J.; Wong, E.; Mohamad, E. Impact of COVID-19 on school populations and associated factors: A systematic review. IJERPH 2022, 19, 4024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Rodríguez, F.M. Fear, Stress, Resilience and Coping Strategies during COVID-19 in Spanish University Students. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, K.L.; Miller, G.F.; Coronado, F.; Meltzer, M.I. Estimated Resource Costs for Implementation of CDC’s Recommended COVID-19 Mitigation Strategies in Pre-Kindergarten through Grade 12 Public Schools—United States, 2020–2021 School Year. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2020, 69, 1917–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinan-Altman, S.; Levkovich, I. Are personal resources and perceived stress associated with psychological outcomes among Israeli teachers during the third COVID-19 lockdown? Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2022, 19, 5634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ato, M.; López-García, J.J.; Benavente, A. A classification system for research designs in psychology. Ann. Psychol. 2013, 29, 1038–1059. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Plano Clark, V.L. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Topp, C.W.; Ostergaard, S.D.; Sondergaard, S.; Bech, P. The WHO-5 Well-Being Index: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Psychother. Psychosom. 2015, 84, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearlin, L.I.; Schooler, C. The structure of coping. JHSB 1987, 19, 2–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimet, G.D.; Dahlem, N.W.; Zimet, S.G.; Farley, G.K. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J. Pers. Assess. 1988, 52, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivan, M.; Halpin, S.; Gee, J.; Makower, S.; Parkin, A.; Ross, D.; Horton, M.; O’Connor, R. The self-report version and digital format of the COVID-19 Yorkshire Rehabilitation Scale (C19-YRS) for Long Covid or Post-COVID syndrome assessment and monitoring. Adv. Clin. Neurosci. Rehabil. 2021, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 27.0; IBM Corp: Armonk, NY, USA, 2017.

- Braun, V.; Clark, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grazzini, M.; Lulli, L.G.; Mucci, N.; Paolini, D.; Baldassarre, A.; Gallinoro, V.; Chiarelli, A.; Niccolini, F.; Arcangeli, G. Return to work of healthcare workers after SARS-CoV-2 infection: Determinants of physical and mental health. IJERPH 2022, 19, 6811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaes, A.W.; Goërtz, Y.M.; Van Herck, M.; Machado, F.V.; Meys, R.; Delbressine, J.M.; Houben-Wilke, S.; Gaffron, S.; Maier, D.; Burtin, C.; et al. Recovery from COVID-19: A sprint or marathon? 6-month follow-up data from online long COVID-19 support group members. ERJ Open Res. 2021, 7, 00141–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, H.M.; Santos, N.W.; Lafetá, M.L.; Albuquerque, A.L.; Tanni, S.E.; Sperandio, P.A.; Ferreira, E.V. Persistence of symptoms and return to work after hospitalization for COVID-19. JBP 2022, 28, 48. [Google Scholar]

- Rass, V.; Ianosi, B.A.; Zamarian, L.; Beer, R.; Sahanic, S.; Lindner, A. Factors associated with impaired quality of life three months after being diagnosed with COVID-19. Qual. Life Res. 2021, 31, 1401–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandasena, H.M.R.K.G.; Pathirathna, M.L.; Atapattu, A.M.M.P.; Prasanga, P.T.S. Quality of life of COVID 19 patients after discharge: Systematic review. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.; Li, X.; Gu, X.; Zhang, H.; Ren, L.; Guo, L.; Liu, M.; Wang, Y.; Cui, D.; Wang, Y.; et al. Health outcomes in people 2 years after surviving hospitalization with COVID-19: A longitudinal cohort study. Lancet Respir. Med. 2022, 10, 863–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadila, M.; Argarini, D.; Widiastuti, S. Factors Related to Quality of Life among Elderly During COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Nurs. Health Serv. 2022, 5, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudel, A.N.; Zhu, S.; Cooper, N.; Roderick, P.; Alwan, N.; Tarrant, C.; Ziauddeen, N.; Yaot, G.L. Impact of COVID-19 on health-related quality of life of patients: A structured review. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0259164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coelho, C.M.; Suttiwan, P.; Arato, N.; Zsido, A.N. On the Nature of Fear and Anxiety Triggered by COVID-19. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, N.; Wei, L.; Wang, H.; Wang, X.; Gao, M.; Hu, X.; Shi, S. Qualitative study of the psychological experience of COVID-19 patients during hospitalization. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 278, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levkovich, I.; Shinan-Altman, S.; Essar Schvartz, N.; Alperin, M. Depression and health-related quality of life among elderly patients during the COVID-19 pandemic in Israel: A cross-sectional study. J. Prim. Care Community Health 2021, 12, 2150132721995448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levkovich, I.; Shinan-Altman, S. Factors associated with work-family enrichment among working Israeli parents during COVID-19 lockdowns. Arch. Environ. Occup. Health 2023, 78, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aghaei, A.; Zhang, R.; Taylor, S.; Tam, C.C.; Yang, C.H.; Li, X.; Qiao, S. Impact of COVID-19 symptoms on social aspects of life among female long haulers: A qualitative study. Res. Sq. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kesuma, E.G.; Purwadi, H.; Putra, D.G.S.; Pranata, S. Social support Improved the quality of life among Covid-19 Survivors in Sumbawa. IJNHS 2022, 5, 319–327. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Tzur, N.; Zanbar, L.; Kaniasty, K. Mastery, social support, and sense of community as protective resources against psychological distress among Israelis exposed to prolonged rocket attacks. J. Trauma Stress 2020, 34, 501–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Yang, X.; Kumar, P.; Cao, B.; Ma, X.; Li, T. Social support and clinical improvement in COVID-19 positive patients in China. Nurs. Outlook 2020, 68, 830–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Kala, M.P.; Jafar, T.H. Factors associated with psychological distress during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic on the predominantly general population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0244630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Truzoli, R.; Pirola, V.; Stella Conte, S. The impact of risk and protective factors on online teaching experience in high school Italian teachers during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Comput. Assist. 2021, 37, 940–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sigurvinsdottir, R.; Thorisdottir, I.E.; Gylfason, H.F. The impact of COVID-19 on mental health: The role of locus on control and internet use. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pöysä, S.; Pakarinen, E.; Lerkkanen, M.K. Patterns of Teachers’ Occupational Wellbeing During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Relations to Experiences of Exhaustion, Recovery, and Interactional Styles of Teaching. Front. Educ. 2021, 6, 699785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E.; Jackson, A.; Hobfoll, I.; Pierce, C.A.; Young, S. The impact of communal-mastery versus self-mastery on emotional outcomes during stressful conditions: A prospective study of Native American women. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2002, 30, 853–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| N | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 25 | 14.7 |

| Female | 145 | 85.3 | |

| Marital status | Single | 16 | 9.4 |

| Married | 132 | 77.6 | |

| Divorced | 17 | 10 | |

| Widowed | 1 | 0.6 | |

| Separated | 4 | 2.4 | |

| Health condition | Very Good | 90 | 53 |

| Good | 58 | 34.1 | |

| Average | 17 | 10.0 | |

| Not so good | 5 | 2.9 | |

| School type | Elementary | 57 | 33.5 |

| Middle school | 52 | 30.5 | |

| High school | 61 | 36 | |

| Chronic diseases | No | 147 | 86.5 |

| Yes | 23 | 13.5 | |

| Vaccinated | No | 10 | 5.9 |

| 1 shot | 16 | 9.4 | |

| 2 shots | 32 | 18.8 | |

| 3 shots | 106 | 62.4 | |

| 4 shots | 6 | 3.5 | |

| Mean | SD | ||

| Age | 40.16 | 1.02 | |

| Number of children | 2.58 | 3.00 | |

| Teaching seniority | 12.51 | 8.77 |

| N | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 2 | 7.6 |

| Female | 24 | 92.4 | |

| Health condition | Very Good | 13 | 50 |

| Good | 12 | 46.1 | |

| Not so good | 1 | 3.9 | |

| School type | Elementary | 7 | 26.9 |

| Middle school | 11 | 42.3 | |

| High school | 10 | 30.8 | |

| Chronic diseases | No | 22 | 84.6 |

| Yes | 4 | 15.4 | |

| Vaccinated | No | 2 | 7.6 |

| Yes | 24 | 92.4 | |

| Mean | SD | ||

| Age | 45.57 | 8.88 | |

| Teaching Seniority | 17.6 | 9.34 |

| % | |

|---|---|

| Fatigue | 43.7 |

| Weakness | 32.2 |

| Sleep difficulties | 27.3 |

| Pain or discomfort | 22.4 |

| Anxiety | 20.7 |

| Dizziness | 20.3 |

| Heart palpitations | 18.0 |

| Depression | 17.0 |

| Difficulty performing daily activities | 16.5 |

| Cognitive difficulties | 16.2 |

| Long-term cough | 15.4 |

| Need for personal care | 15.0 |

| Difficulty with social interaction | 12.0 |

| Communication difficulties | 9.1 |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder | 9.0 |

| Difficulty with mobility | 5.4 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Well-being | - | |||

| 2. Long Covid | −0.40 *** | - | ||

| 3. Sense of control | 0.40 *** | −0.43 *** | - | |

| 4. Social support | 0.31 *** | −0.29 *** | 0.43 *** | - |

| B | SE B | β | t | R2 | F Model | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sense of control | −0.89 | 0.24 | −0.28 | −3.65 *** | 0.25 | 18.96 *** |

| Social support | −0.19 | 0.17 | −0.08 | −0.109 | ||

| Well-being | −0.47 | 0.13 | −0.26 | −3.58 *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Levkovich, I.; Kalimi, E. Long COVID-19 Symptoms among Recovered Teachers in Israel: A Mixed-Methods Study. COVID 2023, 3, 480-493. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid3040036

Levkovich I, Kalimi E. Long COVID-19 Symptoms among Recovered Teachers in Israel: A Mixed-Methods Study. COVID. 2023; 3(4):480-493. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid3040036

Chicago/Turabian StyleLevkovich, Inbar, and Ela Kalimi. 2023. "Long COVID-19 Symptoms among Recovered Teachers in Israel: A Mixed-Methods Study" COVID 3, no. 4: 480-493. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid3040036

APA StyleLevkovich, I., & Kalimi, E. (2023). Long COVID-19 Symptoms among Recovered Teachers in Israel: A Mixed-Methods Study. COVID, 3(4), 480-493. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid3040036