Abstract

(1) Background: The present study aimed to investigate the onset of mental disorders in the six months following hospitalization for COVID-19 in people without a previous psychiatric history. (2) Methods: This was a longitudinal study carried out among adults who had been hospitalized due to COVID-19 infection. Six months after discharge, a series of questionnaires were administered (the World Health Organization Well-being Index (WHO-5), the Patient Health Questionnaire-9, the General Anxiety Disorder Questionnaire-7, and the Drug Abuse Screen Test, among others). Based on these scores, a compound Yes/No variable that indicated the presence of common mental disorders was calculated. A multivariate logistic regression was built to explore the factors associated with the presence of common mental disorders. (3) Results: One hundred and sixty-eight patients (57.34%) developed a common mental disorder in the 6 months following hospital discharge after COVID-19 infection. Three variables were independently associated with the presence of common mental disorders after hospitalization for COVID-19, and the WHO-5 duration of hospitalization), and severity of illness. (4) Conclusions: Among people with no previous psychiatric history, we observed a high incidence of mental disorders after COVID-19 hospitalization. A moderate (1–2 weeks) duration of hospitalization may pose a higher risk of post-COVID-19 onset of a mental health condition than longer or shorter durations of medical hospitalization. Further research is needed to better understand the mechanisms underlying the psychopathological consequences of COVID-19 and their predictors.

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has had major health, social, and economic consequences worldwide [1,2,3]. While mortality and physical morbidity have been the most striking manifestations of the pandemic, mental health has also been adversely impacted. On one hand, there is evidence that COVID-19 disease can directly cause neuropsychiatric disorders [4]. On the other hand, COVID-19 may also indirectly impair mental health due to factors such as economic recession, social isolation, fear of contagion, contagion and/or death of loved ones, and decreased access to health care [5,6]. Understanding the mental consequences of COVID-19 is also one of the current research priorities [7] for contemporaneous and future pandemics.

Previous studies have shown that COVID-19 infection can increase the risk of onset, reactivation, or exacerbation of mental disorders [8]. The mental disorders most likely to debut or worsen as a result of COVID-19 were depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [5] in the early months of the pandemic. Furthermore, studies suggest that the first six months after COVID-19 are those that accumulate the highest incidence [9]. Furthermore, having a previous mental disorder increases the severity and mortality risk of COVID-19 [10].

Interestingly, a few studies have pointed to the role of psychological distress and the traumatic events of the COVID-19 pandemic and the impact on mental health [11,12,13]. Starting for Wuhan (China), in which COVID-19 patients were surveyed after hospital discharge, mild levels of anxiety and depression and low level of PTSD were found, but these mental health symptoms were associated with COVID-19 hospitalization including social stigma associated with this illness and sleep problems [11]. Consistently, an Italian study verified during the first lockdown that during the nocturnal processes, there was greater contact with the processing of trauma caused by COVID-19, while the diurnal processes such as waking thoughts facilitated a functional disconnection to manage this trauma [12]. Additionally, a study in Turkey found that patients discharged after being treated in intensive care units (ICU) with COVID-19 had moderate traumatic stress symptoms [13].

However, after two years from the first outbreak in 2020, the association between COVID-19 and mental disorders remains understudied. In a metanalysis, almost half of the 51 studies included did not examine the severity of COVID-19, and the gender and sociodemographic variables were seldom considered [14]. Another recent literature review about mental health during the first year of the pandemic concluded that life satisfaction and loneliness were stable, which demands accelerating research into the consequences of COVID-19 and its treatment on mental health [15].

The present study aimed to explore the onset of mental disorders in the six months following hospitalization for COVID-19 in Spanish patients without a previous psychiatric history, as the first stage to preliminarily detect the mental health burden derived from this infection. We focused on common mental disorders with a substantial burden to society including mood disorders, anxiety disorders, and alcohol abuse, and examined the association between these mental disorders and the severity of COVID-19 disease.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This study was conducted at the University Hospital Fundación Jiménez Díaz (UH FJD) in Madrid (Spain) as part of a mental health prevention campaign in patients admitted with COVID-19. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the UH FJD and complies with the principles put forward in the Declaration of Helsinki [16]. Patients were recruited in the Psychiatry Services of UH FJD in a catchment area of about 300,000 people in Madrid. These facilities are part of the Spanish National Health Service. The Spanish National Health Service is financed entirely by taxes and offers free coverage to all Spanish citizens and legal immigrants.

2.2. Sample

Participants were adult patients admitted to hospital from January to September 2020 due to COVID-19 infection. Individuals younger than 18 years of age or older than 65 years were excluded due to distinct severity of COVID-19 illness in these groups. History of mental history was reviewed through a structured protocol to ensure that patients were not currently receiving any mental health treatment and had no history of psychological/psychiatric/pharmacological treatment. This was conducted to help reduce the confounding effect of the presence of preexisting mental illness and its treatment.

The inclusion criteria were:

- Aged 18–65 years old;

- No previous history of mental illness;

- Consent to participate in the study.

The exclusion criteria were:

- Aged less than 18 or more than 65 years old;

- Previous history of mental illness (e.g., a diagnosis of depression);

- Patient did not consent to participate in the study even if meeting the inclusion criteria.

2.3. Measures

Six months after hospital discharge, eligible patients were invited to participate, and upon acceptance and providing an oral informed consent by telephone were surveyed. The staff who conducted the telephone interviews included two attending psychiatrists, eight nurses in training, and nine psychology interns. The nurses in training and psychology interns were trained in the administration of the tests and were supervised by phone by the two psychiatrists.

Consequently, the questionnaires were administered by telephone as a screening battery of 28 items including:

- The World Health Organization Well-being Index (WHO-5), which measures the mental well-being [17];

- Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) to identify and quantify depression [18];

- General Anxiety Disorder Questionnaire-7 (GAD-7) to estimate anxiety [19];

- Drug Abuse Screen Test (DAST-10) [20] with four items selected for estimating drug abuse;

- Alcohol use through three items for measuring substance use during the last month (AUDIT-C) [21];

- Primary Care—PTSD for screening of possible PTSD has five items [22].

Using the score in the PHQ-9, GAD-7, AUDIT-C, DAST-10, and PC-PTSD scales, we calculated a compound Yes/No variable that indicated the presence of common mental disorders.

Additionally, the following sociodemographic variables were recorded: age, gender, employment status, marital status, and living status. Other variables measured included psychiatric follow-up and psychopharmacological treatments at the time of the interview and the death of relatives or close friends due to COVID-19.

To measure the overall admission severity due to COVID-19, we used four subclasses of severity of illness and four subclasses of risk of mortality. Risk of mortality and severity of illness measures were derived from the All-Patient Diagnosis Related Group (APR-DRG) algorithm [23]. Severity of illness is defined as the extent to which organ systems lose function or have physiologic decomposition, classified as minor, moderate, major, and extreme. Furthermore, the risk of mortality is a measure of the probability of in-hospital mortality based on secondary diagnosis, age, principal diagnosis, and certain procedure codes with the same classification [24]. In addition, the length of hospitalization for COVID-19 was measured and grouped into categories of less than one week, one to two weeks, and more than two weeks for comparative analysis.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software, version 25.0, was used to perform all of the analysis. A binary logistic regression model was built to estimate the adjusted odds ratios (OR) for the association between the presence of common mental disorder and covariables. All variables that were significant (p < 0.05) in the univariate analysis were included in the multivariate logistic regression as well as age and sex. All tests were two-tailed with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

3. Results

Two hundred and ninety-three patients were included in the study. One hundred and sixty-eight patients (57.34%) developed a common mental disorder (e.g., depression, anxiety, alcohol use, drug abuse, and PTSD) in the 6 months following hospital discharge after COVID-19 infection.

Regarding the association between hospital stay and severity of illness, we found that for patients hospitalized for less than 1 week, 49.7% were classified as major or extreme cases; for patients hospitalized for 1–2 weeks, 78.95% of cases were major or extreme, and for patients hospitalized longer than 2 weeks, 82.46% of cases were major or extreme.

In the multivariate regression model, three variables were independently associated with the presence of common mental disorders after hospitalization for COVID-19: WHO-5 score equal to or over 50 (OR 20.49 CI95% [8.46–49.66; p < 0.0001]), length of hospitalization between 1 and 2 weeks (OR 3.06 CI95% [1.43–6.56; p < 0.004]) and severity of illness (p < 0.0004) (see Table 1). Overall, the multivariate regression model predicted 70% of the cases in the sample, with a sensitivity of 76.5% and a specificity of 62.6%.

Table 1.

Multivariate logistic regression model.

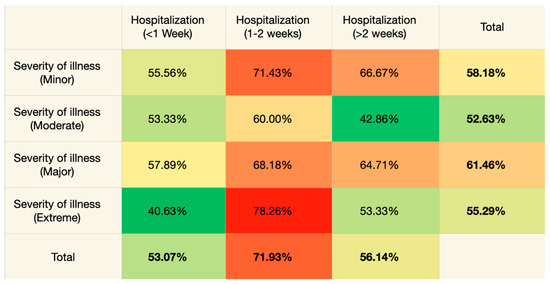

The heat map in Figure 1 shows the patients with respect to the length of hospitalization and severity of illness coded by the presence of common mental disorder, in which the colors are associated with levels of probability of occurrence of both variables: severity of illness, and hospitalization.

Figure 1.

Heat map showing the presence of common mental disorders by hospitalization length and severity (red color: high probability of occurrence of both variables; orange color: mild probability of occurrence of both variables, and green color: low probability of occurrence of both variables).

4. Discussion

The present study aimed to explore the onset of mental disorders in the six months following hospitalization for COVID-19 infection in patients without a previous psychiatric history. We therefore focused on common mental disorders with a substantial burden to society including mood disorders, anxiety disorders, and alcohol abuse and examined the association between these mental disorders and the severity of COVID-19 disease.

4.1. Summary of Results

Within this pandemic context, we found that the severity of illness and risk of mortality, both being highly interrelated, were not strong predictors of common mental disorders in patients after COVID-19, while the length of hospitalization was a strong predictor. To the best of our knowledge, this association has not yet been investigated in studies on the community population who suffered from COVID-19 in the first year of the pandemic and whose mental health burden has been measured after hospital discharge.

Additionally, the multivariate regression found that a WHO-5 score equal to or over 50 was also a powerful indicator, which is in line with the design of the WHO-5 as a questionnaire that determines the overall life disability in the patient and that higher disability is associated with mental illness. Interestingly, we found an inverse correlation between the severity of illness and onset of mental disorders. However, this is in contrast with the percentages shown in the heat map, where the major severity of illness had a higher percentage of patients with common mental disorders (i.e., depression, anxiety, alcohol use, drug abuse, and probable PTSD). This discrepancy can be explained since the overall result was adjusted for other variables, while the heat map was based on a crude (unadjusted) association between the length of hospitalization and severity.

As can be seen by both ORs of the model and the heat map, patients hospitalized for 1–2 weeks were more likely to develop common mental disorders compared to shorter and longer lengths of hospitalization. Thus, a moderate duration of hospitalization for 1–2 weeks seems to be a particularly at-risk group for developing common mental disorders after hospitalization.

4.2. Underlying Mechanisms

The association between COVID-19 infection and onset of mental disorders can be explained from different points of view. On one hand, we must consider the possibility of a biological mechanism of association. Several studies have shown that COVID-19 can damage the brain structure and through neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, and pan-organ endothelial damage [25]. The bidirectional association between inflammation and psychopathology, particularly in depressive disorders, is well-known [26]. However, the association of the severity of illness and onset of mental disorders was inconsistent in our study.

On the other hand, we must also consider psychological mechanisms including reactions to isolation. Therefore, the trauma and psychological factors derived from hospitalization and fear of death could explain the relationship between COVID-19 and the development of mental disorders, aligning with studies that focused on the role of emotional dysregulation during the first lockdown, which is linked to an increase in psychological distress, reaching the proportion of a traumatic global experience [12]. Indeed, similar studies have predictive associations between COVID-19 and the onset of PTSD [11,13,27].

Finally, there is likely to be an interaction between biological and psychological factors that seem to have affected cross-culturally.

4.3. Length of Hospitalization

Length of hospitalization may be a more relevant variable to the patient than severity of illness, as it could be one of the main ways in which patients measure how severe their experience was. It is also indicative of how much time they spent in a situation of stress. Comparing the length of hospitalization, briefer hospitalizations (less than one week) could represent lower psychological impact, while hospitalization of more than two weeks could lead to relief or a positive response after surviving. This is in line with previous studies exploring the so-called post-traumatic growth, where the traumatic experience generates a positive change that leads the patient to a better mental health status [13,28]. In this regard, intermediate hospitalizations of 1–2 weeks might represent the “critical point”, where there is enough time for a stressful situation but not enough for the patient to have post-traumatic growth or develop a positive impact from the cessation of a negative situation.

Regarding improving health care for future patients based on these findings, it is advisable to screen for common mental disorders in patients that have been hospitalized for one week and additionally have symptoms of common mental disorders. It is important that health professionals caring for COVID-19 patients be aware of the possibility of mental disorder rather than the attribution of symptomology entirely to the virus. On positive screening, mental health professionals can help reduce the patient distress level by providing stress coping skills and brief cognitive behavioral therapy, among other psychological techniques (e.g., psychoeducation, online family support group). Furthermore, among the different preventive strategies, a protocol may be necessary to avoid a mental health burden after the patient’s hospital discharge.

With the advent of big data analyses, our results may be incorporated into machine learning (ML) training to assist in refining models of predicting new onset mental illness in COVID-19 and identifying the subgroups of individuals most likely to benefit from psychotherapeutic and pharmacological preventative interventions.

4.4. Limitations

We must consider our findings in light of some limitations. First, we had a relatively small sample size. Second, the mental health assessment of the patients was carried out by telephone, which may have affected the validity. Third, we did not analyze mental health problems including important ones such as suicidality. Finally, we did not use SARS-CoV-2 negative controls from the general population, and ideally, also hospitalized for non-COVID 19 reasons, and not. Those we cannot subtract the effect of mental stressors common to those with and without COVID-19 such as economic hardship, isolation, reaction to friends and relatives becoming ill, and at risk for premature death. We also did not analyze the exacerbation or reactivation of mental illness as well as the occurrence of novel comorbid conditions in individuals with preexisting mental illness. Furthermore, we do not know how generalizable these data are outside of Spain, and even more importantly, to a situation when effective vaccinations and boosting is widespread, and specific treatments for COVID are available for those at increased mortality and severe medical morbidity risk.

4.5. Strengths

The most remarkable characteristic of our report is the timing of its recruitment, specifically during the first year of the pandemic, prior to the introduction of effective vaccines and established anti-SARS-CoV-2 treatments, and before repeated cases of COVID-19 infection.

5. Conclusions

Among the Spanish with no previous psychiatric history, we observed a high incidence of mental disorders following hospitalization for COVID-19. While all survivors of COVID-19 are at risk of developing common mental disorders, those with a moderate inpatient length of stay (1–2 weeks) were at higher risk than those with both briefer and longer hospitalizations. Additionally, an increased risk was also found in those with a WHO Well-being Index (WHO-5) of ≥50. Further research is needed to better predict the prevention of the mental health burden derived from COVID-19 infection and hospitalization, and to better understand the mechanisms underlying the psychopathological consequences of COVID-19.

With the advent of big data analyses, our results may be incorporated into machine learning (ML) training to assist in refining models of predicting new onset mental illness in COVID-19 and identifying the subgroups of individuals most likely to benefit from psychotherapeutic and pharmacological preventative interventions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology, J.C.-D. and E.B.-G.; Data collection, COVID-MH; Writing—original draft preparation, J.C.-D., P.P.D.-A., A.P.-S., S.d.L.-M., M.F.O., P.d.P.-H., A.S.-E.M., I.A.P., C.V.-V., T.T.P., O.L.-F., COVID-MH Collaboration Group and E.B.-G.; Writing—review and editing, O.L.-F., J.C.-D., T.T.P. and S.d.L.-M.; Supervision, E.B.-G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee (CEIC) of the Fundación Jiménez Díaz University Hospital.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

COVID-MH Collaboration group: Raquel Vicente Hernández, Ana Isabel Martínez Gutiérrez, María García Rodríguez, Ana Forján González, Amanda Cecilia Castro Ibáñez, Cristina Moreno de Antonio, Sara Gimeno Sancho, Paula Ramos Ubieto, Nerea Estrella Sierra, Beatriz Villar Sevilla, Belén García Sánchez, Francisco Javier Bonilla Rodríguez, and Natalia Rojo Tejero.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Higgins, V.; Sohaei, D.; Diamandis, E.P.; Prassas, I. COVID-19: From an acute to chronic disease? Potential long-term health consequences. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2021, 58, 297–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.; Huang, L.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Ren, L.; Gu, X.; Kang, L.; Guo, L.; Liu, M.; Zhou, X.; et al. 6-month consequences of COVID-19 in patients discharged from hospital: A cohort study. Lancet 2021, 397, 220–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yesudhas, D.; Srivastava, A.; Gromiha, M.M. COVID-19 outbreak: History, mechanism, transmission, structural studies and therapeutics. Infection 2021, 49, 199–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinakaran, D.; Manjunatha, N.; Naveen Kumar, C.; Suresh, B.M. Neuropsychiatric aspects of COVID-19 pandemic: A selective review. Asian J. Psychiatr. 2020, 53, 102188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reger, M.A.; Stanley, I.H.; Joiner, T.E. Suicide mortality and coronavirus disease 2019—A perfect storm? JAMA Psychiatry 2020, 77, 1093–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Courtet, P.; Olié, E.; Debien, C.; Vaiva, G. Keep Socially (but Not Physically) Connected and Carry on: Preventing Suicide in the Age of COVID-19. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2020, 81, 20com13370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmes, E.A.; O’Connor, R.C.; Perry, V.H.; Tracey, I.; Wessely, S.; Arseneault, L.; Ballard, C.; Christensen, H.; Silver, R.C.; Everall, I.; et al. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: A call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, 547–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazza, M.G.; De Lorenzo, R.; Conte, C.; Poletti, S.; Vai, B.; Bollettini, I.; Melloni, E.M.T.; Furlan, R.; Ciceri, F.; Rovere-Querini, P. Anxiety and depression in COVID-19 survivors: Role of inflammatory and clinical predictors. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 89, 594–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taquet, M.; Geddes, J.R.; Husain, M.; Luciano, S.; Harrison, P.J. 6-month neurological and psychiatric outcomes in 236 379 survivors of COVID-19: A retrospective cohort study using electronic health records. Lancet Psychiatry 2021, 8, 416–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, J.P.; Chesney, E.; Oliver, D.; Pollak, T.A.; McGuire, P.; Fusar-Poli, P.; Zandi, M.S.; Lewis, G.; David, A.S. Psychiatric and neuropsychiatric presentations associated with severe coronavirus infections: A systematic review and meta-analysis with comparison to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, 611–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Baumeister, R.F.; Veilleux, J.C.; Chen, C.; Liu, W.; Yue, Y.; Zhang, S. Risk factors associated with mental illness in hospital discharged patients infected with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 292, 113297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mariani, R.; Gennaro, A.; Monaco, S.; Di Trani, M.; Salvatore, S. Narratives of Dreams and Waking Thoughts: Emotional Processing in Relation to the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 745081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Özgüç, S.; Tanrıverdi, D.; Güner, M.; Kaplan, S.N. The Examination of Stress Symptoms and Posttraumatic Growth in the Patients Diagnosed with COVID-19. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2022, 73, 103274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schou, T.M.; Joca, S.; Wegener, G.; Bay-Richter, C. Psychiatric and neuropsychiatric sequelae of COVID-19—A systematic review. Brain Behav. Immun. 2021, 97, 328–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aknin, L.B.; De Neve, J.-E.; Dunn, E.W.; Fancourt, D.E.; Goldberg, E.; Helliwell, J.F.; Jones, S.P.; Karam, E.; Layard, R.; Lyubomirsky, S.; et al. Mental Health during the First Year of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Review and Recommendations for Moving Forward. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2022, 17, 915–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 2013, 310, 2191–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barreto, M.C.A.; Moraleida, F.R.J.; Graminha, C.V.; Leite, C.F.; Castro, S.S.; Nunes, A.C.L. Functioning in the fibromyalgia syndrome: Validity and reliability of the WHODAS 2.0. Adv. Rheumatol. 2021, 61, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B.W. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Int. Med. 2001, 16, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.B.; Löwe, B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Arch. Int. Med. 2006, 166, 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, H.A. The drug abuse screening test. Addict. Behav. 1982, 7, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins-Biddle, J.C.; Babor, T.F. A review of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT), AUDIT-C, and USAUDIT for screening in the United States: Past issues and future directions. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abus. 2018, 44, 578–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, P.; Jasinski, N.; Zheng, W.; Yadava, A.; Wang, L.; Li, L.; Xu, L.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, L.; Li, W. Psychometric Properties of the Primary Care PTSD Screen for DSM-5: Findings from Family Members of Chinese Healthcare Workers during the Outbreak of COVID-19. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 695678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, K.; Rao, S.; Yarbrough, S.; Nugent, K. All Patient Refined-Diagnosis Related Group Classification for Hospitalized Patients with COVID-19. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2021, 362, 220–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Averill, R.F.; Goldfield, N.; Hughes, J.S.; Wallingford, J.B. All Patient Refined Diagnosis Related Groups (APR-DRGs) Version 20.0: Methodology Overview. Health CM Published 2003. Available online: https://www.hcupus.ahrq.gov/db/nation/nis/APRDRGsV20MethodologyOverviewandBibliography.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2020).

- Kempuraj, D.; Selvakumar, G.P.; Ahmed, M.E.; Raikwar, S.P.; Thangavel, R.; Khan, A.; Zaheer, S.A.; Iyer, S.S.; Burton, C.; James, D.; et al. COVID-19, Mast Cells, Cytokine Storm, Psychological Stress, and Neuroinflammation. Neuroscientist 2020, 26, 402–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beurel, E.; Toups, M.; Nemeroff, C.B. The Bidirectional Relationship of Depression and Inflammation: Double Trouble. Neuron 2020, 107, 234–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GülerBoyraz, D.N.L. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) and Traumatic Stress: Probable Risk Factors and Correlates of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. J. Loss Trauma 2020, 25, 503–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calhoun, L.G.; Tedeschi, R.G. Facilitating Posttraumatic Growth: A Clinician’s Guide; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).