1. Introduction

This study aligns with the theme of the Special Issue, “Power, People, and Performance: Rethinking Organizational Leadership and Management.” This examination of collective Dark Triad (DT) leadership responds directly to the Special Issue’s call to examine how organizational power is reconstituted in contemporary contexts. While many studies have focused on individuals, in this study, we argue that true risk emerges when toxic leaders form alliances. Such coalitions recast ethics into performance tools used to consolidate control, suppress dissent, and redefine organizational identity. By exploring how power is jointly exercised, how employees experience the resulting distortions, and how organizational performance is compromised, this study advances the reconceptualization of leadership addressed in the Special Issue. This work also builds upon the findings of Alowais & Suliman [

1,

2] published in

TPM—Testing, Psychometrics, Methodology in Applied Psychology, which empirically demonstrates the bidirectional contagion of Dark Triad traits between leaders and employees in higher education institutions. Their study offers robust quantitative and qualitative evidence that toxic traits are not only projected by leaders but mirrored by followers, institutionalizing ethical erosion across organizational hierarchies.

1.1. Background and Context

The need to interrogate leadership practices has never been more urgent, as organizations face unprecedented pressures that expose the fragile boundary between ethical ideals and manipulative realities. While much of the literature on leadership has focused on individual behaviors, emerging crises highlight the systemic risks that arise when unethical leaders align, consolidate power, and normalize destructive practices under the guise of organizational progress. These dynamics undermine not only employee well-being but also organizational resilience, performance, and societal trust. Such conceptual explorations are vital today, offering the theoretical rethinking and empirical grounding needed to confront the paradoxes of power, people, and performance that define modern organizational life.

Leadership research has traditionally comprised investigations into positive and transformational qualities such as authenticity, emotional intelligence, and servant leadership [

3]. These models emphasize the ability of leaders to inspire, motivate, and lead their organizations ethically [

4]. However, over the past two decades, more attention has been devoted to “dark” leadership traits, most notably encapsulated in the psychological construct of the Dark Triad: narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy [

5]. All three traits have destructive potential: narcissists crave greatness and adoration, Machiavellians manipulate for personal gain, and psychopaths act impulsively, with little empathy or remorse [

6].

While early research examined these traits individually, current research indicates their effect is most pernicious when leaders who possess these dark tendencies collaborate as a group [

7]. In organizational contexts, groups of leaders who demonstrate strong Dark Triad traits can form strategic “ethics mirages”: behaviors that are presented as ethical yet mask manipulation, exploitation, and unethical decision-making. These groups utilize collective discourses of responsibility, transparency, and corporate social responsibility (CSR) to maintain legitimacy while promoting self-serving agendas [

8]. This study contributes directly to the Special Issue “Power, People, and Performance: Rethinking Organizational Leadership and Management” by highlighting how coalitions of leaders with Dark Triad traits reshape organizational power structures, compromise people-centered cultures, and ultimately distort performance measures. In doing so, this study extends current leadership debates beyond individual pathologies to systemic configurations, offering a novel lens through which to rethink leadership and organizational ethics. Furthermore, this study investigates how coalitions of high-Dark-Triad leaders reconstruct ethical norms within organizations—not merely as isolated incidents of misconduct but as systemic, collectively enacted practices. Building on findings by Alowais & Suliman [

1,

2], we explore how these leaders erode ethical climates by co-opting moral language while engaging in behaviors that undermine trust and accountability. The central problem, therefore, is not simply unethical leadership but the normalization of unethical systems through coordinated moral façades.

1.2. Problem Statement

Scholarship on leadership ethics tends to assume that ethical cultures act as buffers for misconduct. Organizations heavily invest in codes of conduct, corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives, ethics training, and compliance systems [

9]. The assumption is that ethics, once institutionalized, constrain leaders [

10]. Ironically, dark leaders can appropriate ethics as a tool. Decoupling studies show how organizations can maintain a symbolic façade of ethical responsibility whilst diverging from such standards in practice [

11]. Leaders with strong DT traits exploit this decoupling by projecting moral impressions of advocating for CSR initiatives, moral slogans, or integrity charters whilst covertly advancing manipulative or exploitative agendas [

12]. When dark leaders form coalitions, these processes are intensified. A coalition of dark leaders can create what this study refers to as an “ethics mirage”, a collective delusion of moral worth that convinces stakeholders of the organization’s ethical legitimacy while concealing endemic abuse. When this happens, ethics is weaponized as a means of consolidating and protecting coalitional power rather than limiting it. This paradox of ethical culture as both shield and sword presents an existential, theoretical, and practical dilemma for leadership studies.

Although the literature offers a thorough understanding of the corrosive nature of each of the Dark Triad traits, narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy, separately in organizational settings, their dynamic interaction is undertheorized. Literature consistently links these traits to toxic cultures, unethical pro-organizational behavior (UPB), decreased trust, and higher turnover intentions [

13] yet accumulating evidence indicates that when such leaders behave in concert, the impact is not merely additive but synergistic [

14]. Collective dark leadership can amplify harm through the sharing of manipulative expertise, the construction of collective legitimizing narratives, and the reinforcement of reciprocal protection networks that deter scrutiny and accountability [

15].

The way in which these collectives exploit organizational checks is of equal concern. Instruments intended to promote ethical behavior, such as codes of practice, CSR initiatives, and governance structures, can be strategically co-opted to construct “ethics mirages” [

12]. These misleading impressions generate an impression of integrity for external stakeholders while masking exploitative behavior internally. Such dynamics raise pressing questions: How do groups of dark leaders orchestrate illusions of morality, and what chain-reaction effects do they have on employees, organizational resilience, and generalized societal trust? Addressing this gap is essential for advancing theory and informing practice. Unlike prior research that isolated narcissistic or Machiavellian leaders as individual disruptors [

16,

17], this research conceptualizes collective dark leadership alliances in which multiple high-DT actors synchronize manipulation, moral justification, and control. This shift from

individual pathology to

coalitional process distinguishes this research from earlier studies on toxic leadership frameworks and marks its primary theoretical innovation. Although literature has extensively cataloged dark traits in individuals, there is little theorization of their collective enactment, especially regarding how groups of dark leaders jointly reconstruct ethical discourse to legitimize domination. This research addresses the absence of an integrative framework explaining how such coalitions form, maintain power, and distort organizational ethics.

1.3. Research Aim and Objectives

To ensure greater alignment between the research objectives and questions, this study explicitly links its empirical focus to its practical implications. While RQ1 and RQ2 explore the collective behavioral and discursive mechanisms through which Dark Triad coalitions sustain moral façades, RQ3 extends these insights to examine the organizational and human outcomes that emerge from such ethical distortions. The findings derived from RQ3 directly inform Objective 5 by identifying governance, HR, and regulatory interventions that can mitigate the risks posed by collective dark leadership. Specifically, insights on how “ethics cartels” institutionalize moral manipulation are translated into recommendations for leadership screening, whistle-blower protections, and accountability frameworks. This explicit connection positions this study not only as a theoretical contribution to leadership and ethics research but also as a practical resource for organizational reform and policymaking. This study aims to analyze how collective Dark Triad leadership creates ethics mirages within organizations and to assess the consequences of such dynamics. Specifically, it pursues the following objectives:

To summarize the existing literature on the Dark Triad and leadership since 2015, searching for patterns that can be applied to collective leadership.

To investigate processes through which groups of DT leaders instrumentalize discourses of ethics, responsibility, and legitimacy.

To evaluate the employee- and organizational-level outcomes of such collective behavior.

To propose a conceptual model of how collective dark leadership sustains ethics mirages.

To highlight practical implications for governance, HR policies, and regulatory interventions.

1.4. Research Questions

While much of the literature has examined the influence of individual Dark Triad (DT) traits in leaders, collective DT leadership presents unique mechanisms of influence. As works by Alowais & Suliman [

1,

2] demonstrate, individual-level DT behaviors often disrupt ethical climates through moral disengagement but coordinated DT leadership amplifies this effect by constructing a shared ethical front that disguises individual misconduct under collective legitimacy. In this view, power becomes more diffusely concentrated yet more resilient to accountability—transforming ethics into a shared rhetorical resource rather than a personal stance [

1]. Building on the foregoing synthesis, the following research questions emerged to guide the inquiry:

RQ1: In what ways do groups of Dark Triad leaders collectively behave to create and sustain ethics mirages?

RQ2: What impression management mechanisms, accountability shielding tactics, and cultural manipulation behaviors are most prevalent in these alliances?

RQ3: What are the consequences of collective Dark Triad leadership for organizational ethics, employee well-being, and stakeholder trust?

1.5. Contribution to Literature

Despite extensive research on individual Dark Triad leaders, limited attention has been paid to how multiple high-DT individuals interact to construct a collective moral order. With this gap, it remains unclear how ethics becomes a shared mechanism of domination rather than a concern of individual deviation. To address this gap, this research involved a qualitative, article-based document analysis of 55 peer-reviewed studies (2015–2025) to uncover the systemic patterns and discursive strategies that allow Dark Triad coalitions to sustain moral façades and institutionalize misconduct. This study’s theoretical contribution lies in reframing ethics as a collective instrument of power, while its practical contribution is the proposal of governance and HR reforms to detect and disrupt collusive moral alliances.

This research contributes to the literature on destructive leadership by expanding research on Dark Triad traits from the individual to the collective level. Much of the existing research has focused on the influence of single narcissistic CEOs or Machiavellian managers on organizational culture and performance [

18]. However, organizations are often dominated not by individuals but by leadership coalitions, boards, or executive teams, where individuals with dark personalities are more likely to operate in strategic collaboration with one another. This study fills that gap by investigating how alliances among high Dark Triad leaders form systemic control patterns, heighten manipulation, and suppress dissent, thereby anchoring unethical behavior [

7].

This research also contributes to research on ethical fading, impression management, and organizational culture. It shows how organized dark leaders can form “ethics mirages”, façades of integrity that give stakeholders the impression of moral legitimacy while concealing wrongdoing. By integrating insights into leadership ethics, organizational behavior, and corporate governance, this research develops a more integrated and interdisciplinary model, contributing not only to academic theory but also to practice and policymaking, providing applied diagnostics to prevent and identify collective unethical leadership dynamics.

1.6. Research Structure

This paper is structured with six interrelated chapters. Section One is an introduction, providing the background to this study, problem statement, research aims, and the expected contributions of the research. Section Two is a review of the literature on the Dark Triad, collective leadership, impression management, and how ethical mirages develop within organizations. The term “ethics mirage” captures the phenomenon in which ethical behavior is performatively enacted but not internally anchored—a dynamic supported by works from Alowais & Suliman [

1,

2], who found that leaders may simulate ethical leadership to build ethical capital while privately engaging in self-serving behaviors. This aligns with Bandura’s theory of moral disengagement, where justifications and distortions of ethical norms allow unethical actions to persist under the guise of moral legitimacy. Mirage, thus, is not the absence of ethics, but the simulation of them for strategic gain. Section Three presents the theoretical framework through the utilization of Human Capital Theory, Agency Theory, and Social Exchange Theory in explaining collective dark leadership dynamics. Section Four lays out the methodology, explaining the qualitative synthesis approach applied to 55–60 peer-reviewed articles published between 2015 and 2025. Section Five lays out the analysis and discussion, with emergent themes of Ethics Cartels, Mutual Cover, Cultural Capture, and Employee Survival strategies. Section Six lays out the conclusion and implications, synthesizing the findings, highlighting the contributions of the research, and indicating possibilities for future research. In summary, this research sheds light on how destructive leadership may thrive under a façade of ethicality, evoking urgent questions about organizational accountability and resilience.

2. Literature Review

The dynamics examined in this study are particularly salient to understanding power, people, and performance in contemporary organizations, aligning directly with the aims of this Special Issue. In keeping with the Special Issue’s agenda, this review highlights how collective DT leadership reshapes the triad of power, people, and performance. First, it reframes power by showing how leaders coordinate to protect one another and enforce a shared moral façade, creating what we term the

Ethics Cartel. Second, it foregrounds people, emphasizing the psychological toll on employees who must navigate an environment in which ethics are weaponized. Third, it interrogates performance, revealing how organizational outcomes decline when cultural integrity is corroded. This three-dimensional perspective extends existing work on toxic leadership and positions this study within the rethinking of organizational leadership that is the theme of the Special Issue. Recent work by Alowais & Suliman [

1] highlights the paradox in which leaders appear to foster ethical climates while engaging in behaviors that are internally inconsistent with those values. This underscores the need to distinguish between perceived ethical behavior and genuine moral commitment. Rather than present organizational case studies, we emphasize empirical findings that document how DT traits moderate the effectiveness of ethical leadership—illustrating that even well-designed ethical systems can be undermined by toxic coalitional dynamics.

2.1. Foregoing Scholarship

To provide a comprehensive historical view of the field, this study extends its review to foundational works from 2015 onward rather than emphasizing only recent contributions. Earlier studies such as Spain et al. and Boddy [

17,

19] established the initial theoretical boundaries of destructive and narcissistic leadership, identifying how moral reasoning can be subordinated to instrumental control. Integrating these earlier analyses enables a longitudinal understanding of how the notion of toxic leadership evolved toward the present concept of “collective Dark Triad leadership.” This chronological mapping highlights the intellectual progression from individual pathology to systemic ethical distortion.

Research on leadership has typically been based on narratives of vision, inspiration, and leaders’ ability to motivate their followers to contribute to shared goals. Classical and contemporary models, ranging from servant and transformational leadership to authentic and ethical leadership, have centered on the good aspects of leadership behavior and how they translate to organizational performance [

20,

21]. However, a growing body of research warns that leadership is not always good. Destructive leadership, which is evident in leaders with traits of narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy, demonstrates how power can be exercised not for the greater good but to facilitate self-serving, coercive, and unethical behaviors [

22].

While most of the literature on dark leadership identifies individual dark traits, scholars are increasingly recognizing the collective dynamics of dark leadership and how groups of leaders with a shared set of destructive characteristics collaborate, support each other, and influence organizational systems’ structures [

7]. The shift from individual to collective perspectives reveals more complex and refined organizational structures, particularly corporate governance, in which executive power coalitions can taint control and enable moral degradation [

12].

This section critically examines the literature on dark leadership and organizational outcomes. It explains the theoretical foundations (

Section 2.1), examines destructive leadership constructs (

Section 2.2), addresses organizational consequences (

Section 2.3), and integrates corporate case studies (

Section 2.4). The section concludes with an overview of research gaps and the novel contributions of this research (

Section 2.5). Recent works by Alowais & Suliman [

1,

2] highlight the paradox in which leaders appear to foster ethical climates while engaging in behaviors that are internally inconsistent with those values. This underscores the need to distinguish between perceived ethical behavior and genuine moral commitment. Rather than present organizational case studies, we emphasize empirical findings that document how DT traits moderate the effectiveness of ethical leadership—illustrating that even well-designed ethical systems can be undermined by toxic coalitional dynamics.

Table 1 consolidates 16 key scholarly contributions from 2007 to 2025 that underpin the study’s conceptual framework. Early foundational works [

16,

19] define the dark leadership terrain, while more recent studies [

1,

2,

12] introduce systemic, collective, and cultural dimensions. The table reveals a clear progression: from individual-level dark traits to group dynamics, façade ethics, and institutional feedback loops. Collectively, these works validate the study’s shift toward understanding Dark Triad leadership as a collaborative, performative, and systemically reinforced phenomenon.

From the 55 peer-reviewed articles analyzed in this study, 16 are presented here as foundational to the paper’s theoretical, methodological, and conceptual scaffolding (see

Table 1). These pivotal works were selected for their critical influence on the evolution of dark leadership theory—from early definitions of destructive traits to recent frameworks on collective toxicity, ethical fading, and system-level contagion effects. This curated subset serves as the conceptual backbone of the study, offering key paradigms that frame the Ethics Mirage, Ethics Cartel, Mutual Cover, and Cultural Capture. The remaining 39 sources—while not presented in the table—enrich the thematic analysis across

Section 2.3,

Section 2.4 and

Section 2.5, providing empirical breadth, sectoral diversity, and contextual depth. Together, the full corpus ensures both conceptual rigor and comprehensive synthesis, as required for a qualitative meta-analysis of this scale.

2.2. Theoretical Foundations of Dark Leadership

The theoretical grounding of dark leadership aligns directly with the Special Issue’s call to rethink organizational power. Much of the existing literature on narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy conceptualizes dark leadership as an individual phenomenon. However, as this study emphasizes, systemic risks emerge when multiple leaders share dark traits and collectively reconstruct moral frameworks. This coalition-driven approach reframes power as not just hierarchical but as negotiated and reinforced among toxic leaders. By integrating perspectives from narcissistic leadership theory and the ethics of leadership change, the present study supports the Special Issue’s agenda to reconceptualize how leadership power is exercised and maintained in complex organizational contexts.

2.2.1. Leadership Studies and the Dark Side

Traditional leadership scholarship has long favored positive paradigms, with leaders often described as visionary, inspirational, and morally responsible agents. Transformational leadership, for instance, emphasizes the development of a motivating vision, intellectual stimulation, and empowerment of others [

27]. Kadir [

28] frames ethical leadership as action based on fairness, integrity, and the promotion of follower welfare. Similarly, servant leadership prioritizes others’ growth, community building, and stewardship [

29]. These dominant theories both inform practice and research, validating the image of leadership as inherently prosocial.

However, this “heroic bias” has been challenged increasingly vigorously. Scholars have argued that leadership also exists in exploitative, coercive, or destructive forms [

30]. Destructive leaders will harm organizational performance, erode follower trust, and create toxic workplaces, often with short-term results that mask long-term damage [

22]. According to Chen [

15], the Toxic Triangle model is a classic theory explaining this phenomenon. There are three interdependent forces identified by the model: (1) destructive leaders, who are characterized by traits of narcissism, abusive supervision, or authoritarianism; (2) vulnerable followers, who may be conformers (acting due to unsatisfied needs) or colluders (sharing the same values or goals as the leader); and (3) supporting environments, such as crises, poor governance structures, or unstable markets, which provide fertile ground for destructive behavior.

This system’s perspective stands in contrast to earlier depictions of pathology in the leader’s personality, locating dark leadership in the dynamics among personal, relational, and structural forces. For example, at Enron, narcissistic yet charismatic managers thrived in an unregulated energy sector where compliance culture was low, high follower dependence was encouraged, and risky aggression was culturally endorsed [

30]. Therefore, the Toxic Triangle emphasizes that dark leadership is seldom a singular aberration and is more likely situated within larger organizational and societal contexts.

2.2.2. Dark Triad Personality Traits

The Dark Triad of narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy has emerged as one of the most significant models for explaining destructive leadership [

5]. For each trait, there are unique yet intersecting accounts of harmful leader conduct.

Narcissism is characterized by arrogance, grandiosity, and a need for excessive admiration [

31]. Narcissistic leaders are likely to display charisma and confidence, which inspire followers, especially in periods of uncertainty [

26]. Their entitlement and hypersensitivity to criticism tend to result in poor listening, overconfidence, and unethical risk-taking. The case of Theranos evidences this dynamic: Elizabeth Holmes had visionary charisma but displayed narcissistic traits that suppressed dissent and encouraged secrecy, leading to the organizational downfall of epic proportions [

32].

Machiavellianism involves strategic manipulativeness, emotional callousness, and the pragmatic pursuit of organizational or personal benefit [

33]. Machiavellian executives are adept at political backstabbing and managing organizational narratives, with a propensity to increase personal power at the expense of ethical integrity. Research indicates that such leaders exploit follower dependence and ambiguity to gain compliance [

25]. For instance, in the Dieselgate Volkswagen scandal, managers strategically manipulated emissions tests and rationalized deceit as a competitive necessity, actions that are perfectly Machiavellian [

34].

The most harmful of the Dark Triad traits is psychopathy, which is associated with impulsiveness, callousness, a lack of empathy, and thrill-seeking [

8]. Unlike narcissism or Machiavellianism, psychopathy is always connected with unethical workplace conduct, bullying, and fraud [

35]. Instances such as the collapse of Lehman Brothers have been partially attributed to psychopathic tendencies in leaders who were more concerned with personal accumulation and aggressive expansion than systemic stability [

36].

Meta-analyses suggest that while narcissistic and Machiavellian approaches may yield immediate gains, such as aggressive growth, daring action, or enhanced external reputation, they decrease organizational resilience, trustworthiness, and moral behavior in the long term [

6]. Psychopathy, however, is mostly associated with long-term harm in the sense that it results in wrongdoing, lawsuits, and financial collapse [

37]. Together, the Dark Triad offers a compelling explanation for why toxic leaders persist, prosper, and are likely to remain undetected until organizational damage is widespread.

2.2.3. Ethical Fading and Impression Management

In addition to personality traits, dark leadership is linked to cognitive and behavioral processes that normalize immorality. Engelen & Nys [

24] introduced the term ‘ethical fading’ to describe the increasing tendency to no longer perceive actions as ethical in nature but rather reduce them to neutral or purely technical concerns. When leaders prioritize shareholder value, performance standards, or innovation over ethics, ethical fading occurs.

Dark leaders deliberately exploit ethical fading by redefining wrongdoing as “business as usual.” By managing impressions, they strategically project organizational images of responsibility, transparency, and innovation while concealing harmful practices [

12]. An example of this is Volkswagen’s Dieselgate scandal, in which leaders justified the use of “defeat devices” to manipulate emissions tests. Internally, the misconduct was packaged as a technical solution to regulatory issues, while externally, the company projected an image of sustainability and environmental responsibility [

34]. This duality is an example of the destructive dynamics of ethical fading and impression management, in which leaders simultaneously eroded internal integrity and managed external legitimacy.

The broader implication is that destructive leadership can only be fully understood in terms of the organizational cultures and institutional pressures that allow ethical fading. Empirical research by Nguyen et al. [

23] finds that ethical fading is more pronounced within competitive, high-pressure environments where leaders are focused on outcomes at any cost. Additionally, impression management tactics such as symbolic corporate social responsibility campaigns often insulate dark leaders from external scrutiny, allowing destructive practices to go unnoticed until they are revealed by whistleblowers, regulators, or media.

2.3. Destructive Leadership Constructs

Empirical and theoretical contributions to research on destructive leadership outcomes, the Toxic Triangle, and moral disengagement mechanisms, such as Padilla e al., Thoroughgood et al., and Schyns & Schilling [

16,

25,

38] respectively, anchor this study’s argument that destructive leadership transcends individual pathology. Each conceptual argument in this review is substantiated by peer-reviewed evidence, reinforcing this study’s academic rigor. Research on destructive leadership typically emphasizes individual styles, such as abusive supervision, laissez-faire leadership, or authoritarianism, yet this framing underestimates how such constructs scale when multiple leaders engage in collective destructive practices. The Special Issue emphasizes

people as central to leadership debates, and this study builds that perspective by highlighting the psychosocial toll on employees when destructive leadership is institutionalized through coalitions. Constructs such as impression management, moral disengagement, and façade ethics become amplified in groups, producing an environment in which employees are forced into complicity. By situating destructive leadership in collective rather than individual terms, this study advances the Special Issue’s call to rethink leadership as a shared cultural and structural process rather than a set of isolated behaviors.

2.3.1. Narcissistic Leadership

Grandiosity, dominance, and a requirement for admiration characterize narcissistic leadership. Narcissistic leaders are visionary and charismatic, motivating their followers based on what they envision and at first assume. Behind this façade is a self-oriented approach in which organizational results are secondary to personal drive [

39]. Narcissistic leaders do not permit opposition, accumulate power, and prefer to control organizational histories to present themselves as irreplaceable.

One such classic example is Jeffrey Skilling of Enron, whose management style was the very epitome of narcissism in a corporate culture. Skilling consistently dismissed skeptics who raised concerns over the company’s questionable accounting practices, projecting confidence to mask financial weakness [

40]. His self-declared brilliance and infallibility created a culture that stifled dissent and enforced homogeneity among employees. Enron’s collapse, one of the largest corporate failures ever, is an example case in point of how narcissistic overconfidence and self-congratulation distort risk perception and undermine organizational integrity.

2.3.2. Machiavellian Leadership

Machiavellian managers are clever manipulators who use cunning, deception, and opportunism to control power. Unlike narcissists, who are motivated by ego and admiration, Machiavellians are pragmatic and utilitarian in seeking control [

25]. Machiavellians do well in corporate environments where political maneuvering and strategic alliances characterize advancement.

Elizabeth Holmes of Theranos best exemplifies Machiavellian tendencies. Holmes successfully controlled her public image as a visionary entrepreneur and overestimated the capabilities of her company’s blood-testing technology. Through powerful board members and leveraging investor optimism, Holmes propped up the legitimacy of Theranos for over a decade, even when whistleblowers in the firm doubted it [

32]. Holmes’ behavior shows how Machiavellianism further enhances fraudulent operations by exploiting trust, authority, and organizational transparency. Ultimately, however, this manipulation collapses under rigorous external scrutiny.

2.3.3. Psychopathic Leadership

Psychopathic leadership is the darkest component of the Dark Triad. Corporate psychopaths are defined by a lack of empathy, impulsiveness, and desire for dangerous behavior [

8]. They often mask their cruelty with superficial charm, but their decision-making destroys long-term solidity.

The collapse of Lehman Brothers, led by CEO Dick Fuld, illustrates the impact of psychopathic management. Fuld was notorious for being merciless, bullying junior staff members, and disregarding systemic weaknesses that imperiled the global financial system [

41]. His fixation on expansionist growth and disregard for warnings led to unsustainable behaviors, ultimately resulting in the 2008 financial crisis. These scenarios reveal the degree to which psychopathic leadership inspires cultures of blind conformity and fear, stifling ethical protest and accelerating organizational meltdown.

2.3.4. Collective Dark Leadership

While most relevant studies have focused on individuals, recent studies identify the concept of collective dark leadership alliances, in which toxic leaders undermine accountability and perpetuate misconduct in organizational systems [

7]. When multiple leaders cover one another’s nefarious activities, dark leadership shifts from the expression of personality traits to an organizational pathology.

Volkswagen’s emissions scandal is a good example. Senior executives all played a part in collectively falsifying emissions data, embedding deception into business culture [

42]. Similarly, at Wells Fargo, systemic pressure from different tiers of leadership resulted in the opening of fake accounts, institutionalizing wrongdoing amongst thousands of members of staff. These are examples of how collective dark leadership aggravates harm by diffusing responsibility, eradicating accountability, and institutionalizing corruption. Collective dynamics, therefore, represent an insidious type of dark leadership that extends past individual pathology and transforms whole organizations into instruments of illegality.

2.4. Organizational Consequences of Dark Leadership

The organizational outcomes of dark leadership underscore the Special Issue’s third dimension: performance. Prior work has shown how toxic leaders erode trust, increase cynicism, and damage employee well-being. This study demonstrates how those consequences intensify when dark leaders act in concert. Coalition-based leadership enables Mutual Cover, reduces accountability, and reconfigures organizational culture into a system that privileges loyalty to leaders over ethical integrity. As a result, organizational performance declines—not only in terms of productivity but also in reputation, innovation, and long-term sustainability. These findings advance the Special Issue’s focus by showing that destructive leadership is not only about the moral failure of individuals but also about the systemic risks that arise when organizations normalize coalitions of unethical leaders.

2.4.1. Financial Illegality and Scandals

The most blatant consequence of dark leadership is financial illegality on a mass scale that not only destroys companies but also destabilizes industries and economies. At Enron, the narcissistic leadership of Jeffrey Skilling nurtured fraudulent accounting practices that eventually wiped out over USD 74 billion in shareholder value [

40]. Similarly, the collapse of Lehman Brothers, catalyzed by psychopathic risk-taking and governance complacency, triggered the 2008 financial crisis and led to systemic contagion [

41]. More recently, the events at Theranos illustrate how Machiavellian leadership sustains deception by manipulating investors and suppressing dissension, directly threatening patient safety [

32]. These examples illustrate that the financial corruption enabled by dark leadership tends to cross organizational boundaries, creating waves through global markets and eroding public faith in corporate governance [

43].

2.4.2. Organizational Culture and Employee Well-Being

In addition to economic damage, dark leadership undermines organizational culture, replacing cooperation with fear, silence, and obedience [

44]. Under Travis Kalanick, Uber showed this trajectory: while the company achieved meteoric ascent, its hyper-aggressive culture led to sexual harassment scandals, ethical failures, and eventual reputational collapse [

45]. Empirical evidence confirms that toxic leadership undermines psychological safety, increases stress and burnout, and increases turnover intentions [

22]. In this context, employees disengage from innovation and ethical responsibility, creating a dysfunctional cycle.

2.4.3. Governance Failure and Regulatory Capture

Dark leadership is fostered where governance systems are weak or compromised. Siemens’ global bribery scandal is a quintessential example of systemic governance failure, where collective complicity and ineffective oversight allowed endemic corruption to thrive in international markets [

46]. Weak boards, regulatory capture, and poor whistleblower protections usually shield wayward leaders from responsibility [

47]. These conditions not only perpetuate undesirable behavior but also erode public trust in institutions meant to shoulder responsibility. Accordingly, strengthening governance through the establishment of independent boards, effective audit committees, and robust whistleblower protections is key to avoiding the toxic organizational consequences of dark leadership.

2.5. Case Studies of Dark Leadership in Practice

While theoretical commentaries on dark leadership have identified its psychological and organizational causes, case studies offer real-life examples of the ways in which toxic behavior manifests. Below, case studies demonstrate how narcissism, psychopathy, Machiavellianism, and toxic cultural forces have brought down businesses, harmed stakeholders, and resulted in systemic consequences.

Table 2 presents six emblematic case studies that were selected from a wider set of documented leadership failures referenced throughout this paper. These cases serve as paradigmatic illustrations of how Dark Triad traits manifest in real-world organizational collapse. Each example represents a distinct yet interconnected dark trait expression—narcissism, Machiavellianism, psychopathy, and toxic culture—and demonstrates the tangible consequences of destructive leadership when embedded within institutional systems.

While these cases are deeply analyzed for their explanatory power, they are not exhaustive. Additional organizational examples—spanning government, non-profit, and transnational institutions—are incorporated to support broader thematic generalizations. Thus, the six featured cases function as anchoring narratives for the paper’s analytical framework, exemplifying the mechanisms of Mutual Cover, Cultural Capture, and the Ethics Mirage in action.

2.5.1. Enron

The collapse of Enron is one of the most well-known examples of corporate failure due to toxic leadership. CEO Jeffrey Skilling and Chairman Kenneth Lay exhibited enormous narcissism and hubris, manipulating financial statements to present a vision of relentless growth [

40]. Their excessive reliance on mark-to-market accounting and complex Special Purpose Entities (SPEs) concealed massive debt, deceiving investors and regulators. From a theoretical perspective, their approach comprised both impression management and ethical fading, with leaders rationalizing misconduct as standard business practice [

24]. Enron’s culture was aggressively competitive and contemptuous of ethics, giving rise to an atmosphere of silence among staff members, who feared reprisal. Ultimately, its downfall wiped out USD 74 billion in shareholder value and destroyed employee pensions, demonstrating the way in which narcissistic leadership destroys not only organizations but also employee livelihoods and trust from the wider public.

2.5.2. Volkswagen

The Dieselgate scandal at Volkswagen exemplifies collective dark leadership at the system level. Executives coordinated the installation of defeat devices for passing emissions tests, cheating regulators and consumers around the world [

34]. Unlike the case of Enron, in which individualistic narcissistic personalities were at the center, Volkswagen’s unethical actions were based on collective collusion and toxic groupthink. Pressure for global car market dominance from leadership meant that the company culture prioritized performance demands over ethical concerns. This aligns with McAleer (2025)’s “normalized corruption” theory [

48], which posits that evil becomes an organizational norm. The consequences were catastrophic: billions in fines, reputational devastation, and loss of consumer confidence in the German auto sector. This case shows how dark leadership, being systemic, diffuses responsibility through hierarchies, rendering accountability diffuse and unchangeable.

2.5.3. Theranos

Elizabeth Holmes’s leadership of Theranos is the ultimate example of Machiavellian impression management and manipulation. Holmes cultivated a charismatic presence modeled after Steve Jobs, adopting calculated intimidation and secrecy as a way of ensuring investor confidence in the event of technological collapse [

32]. Employees who complained were silenced by intimidatory legal threats, exemplifying tyrannical and poisonous leadership. This case of dark leadership is particularly significant because it transcended financial manipulation, putting patients in direct danger using untrustworthy blood-testing equipment. This illustrates the extent to which dark leadership can transcend financial loss and result in risks to human health and public security. The Theranos scandal highlights the necessity of whistleblower protection and transparent oversight processes to prevent stakeholders from being targeted by dominating but charismatic leaders.

2.5.4. Wells Fargo

The case of account fraud at Wells Fargo illustrates how group leadership pressures can facilitate deviance. Driven by unrealistic sales targets, executives established performance goals that led workers to create millions of imaginary accounts without their customers’ consent [

49]. This is a case of destructive leadership in the form of system toxic culture and not individual pathology. The workers revealed that they were under pressure to engage in unethical behavior to maintain employment, demonstrating compliance with authority [

50]. The scandal damaged the bank’s reputation, cost billions in fines, and led to widespread employee layoffs. More importantly, it illustrates how dark leadership can be embedded in organizational arrangements in which short-term fiscal gains are prioritized over ethical considerations, creating what Zaghmout & Balogun [

51] term “ethical blind spots.”

2.5.5. Uber

Uber grew rapidly under CEO Travis Kalanick, but it came to be associated with a poisonous corporate culture. Kalanick’s aggressive leadership centered on disruption and growth at the cost of human well-being and ethical behavior [

52]. Sexual harassment, discrimination, and a brutally competitive culture were observed, resulting in fear and silence among employees. Uber is a glaring example of how poisonous leadership impacts employee happiness, with workers internalizing stress and burnout due to ongoing pressure to deliver. Ultimately, long-term public outcry and insider revolt led to Kalanick’s resignation. This case demonstrates that dark leadership not only ruins long-term organizational sustainability but also destroys employees’ trust, morale, and commitment, making operations unsustainable under the weight of public demands for ethical business practices.

2.5.6. Lehman Brothers

The downfall of Lehman Brothers during the global financial crisis is an example of psychopathic risk-taking and governance failure. CEO Richard Fuld took risky mortgage-backed securities and aggressive leverage while disregarding warnings from regulators and analysts [

53]. His autocratic management style and intolerance of criticism silenced dissenting warnings within the company, leaving it horribly exposed. On a theoretical level, Fuld’s behavior aligns with psychopathic characteristics: manipulativeness, lack of empathy, and irresponsible risk-taking [

8]. The consequences reached far beyond the company, causing systemic financial collapse and deepening the global recession. This case demonstrates how dark leadership, when embedded in an institutionally impactful system, can destabilize entire economies, making governance and regulation matters of international public concern.

2.5.7. Synthesis

There are some recurring themes in these case examples. First, dark leadership is rarely ever isolated; it is usually supported by a toxic culture, weak governance, and regulatory capture. Second, even when individual pathologies such as narcissism or psychopathy are at play, pressures within an organization and group dynamics amplify their dystopic potential. Third, the impacts of dark leadership extend beyond economic loss to include cultural debasement, injury to workers, public health risks, and even systemic economic meltdown. These examples show that dark leadership is not merely one failure but a structural and cultural problem whose solution requires stern governance, ethical leadership, and system safeguards.

2.6. Research Gap

Although research on toxic leadership has grown exponentially, there are still critical gaps that limit theory development and practical applications. Much of the existing research still centers on the single leader as the unit of analysis, emphasizing traits such as narcissism, psychopathy, or Machiavellianism. While this approach has generated some helpful findings, it ignores the extent to which destructive leaders tend to operate in webs of power, conspiring against one another and affirming and legitimizing each other’s abuse. The theory of collective dark leadership thus remains undertheorized and underexplored, even though it is clearly implicated in most business scandals [

7].

There is a second gap in the research about ethical fading and impression management. The existing literature tends to mention these phenomena parenthetically but rarely considers how leadership teams collectively construct what one might refer to as ethics mirages—impression management frames that lead stakeholders to view unethical actions as acceptable or even noble. Scandals, as described by Ughulu [

12], tend to center around groups of executives who work collaboratively to sustain deception rather than individual “bad apples.”

Third, literature continues to have a Western bias, with a prevailing focus on US and European cases. The number of comparative studies in other cultures and regulatory settings is limited, making it difficult to generalize the dynamics of destructive leadership and how it may manifest differently outside of Western settings.

Finally, studies have rarely blended studies of leadership, organizational behavior, and corporate governance, and there is weak convergence between these fields. Thus, analyses may fail to capture how micro-level abusive behaviors are accompanied by macro-level governance failures.

This research addresses these gaps by examining collective dynamics of dark leadership, integrating knowledge between fields, and applying theoretical frameworks to empirical corporate case studies.

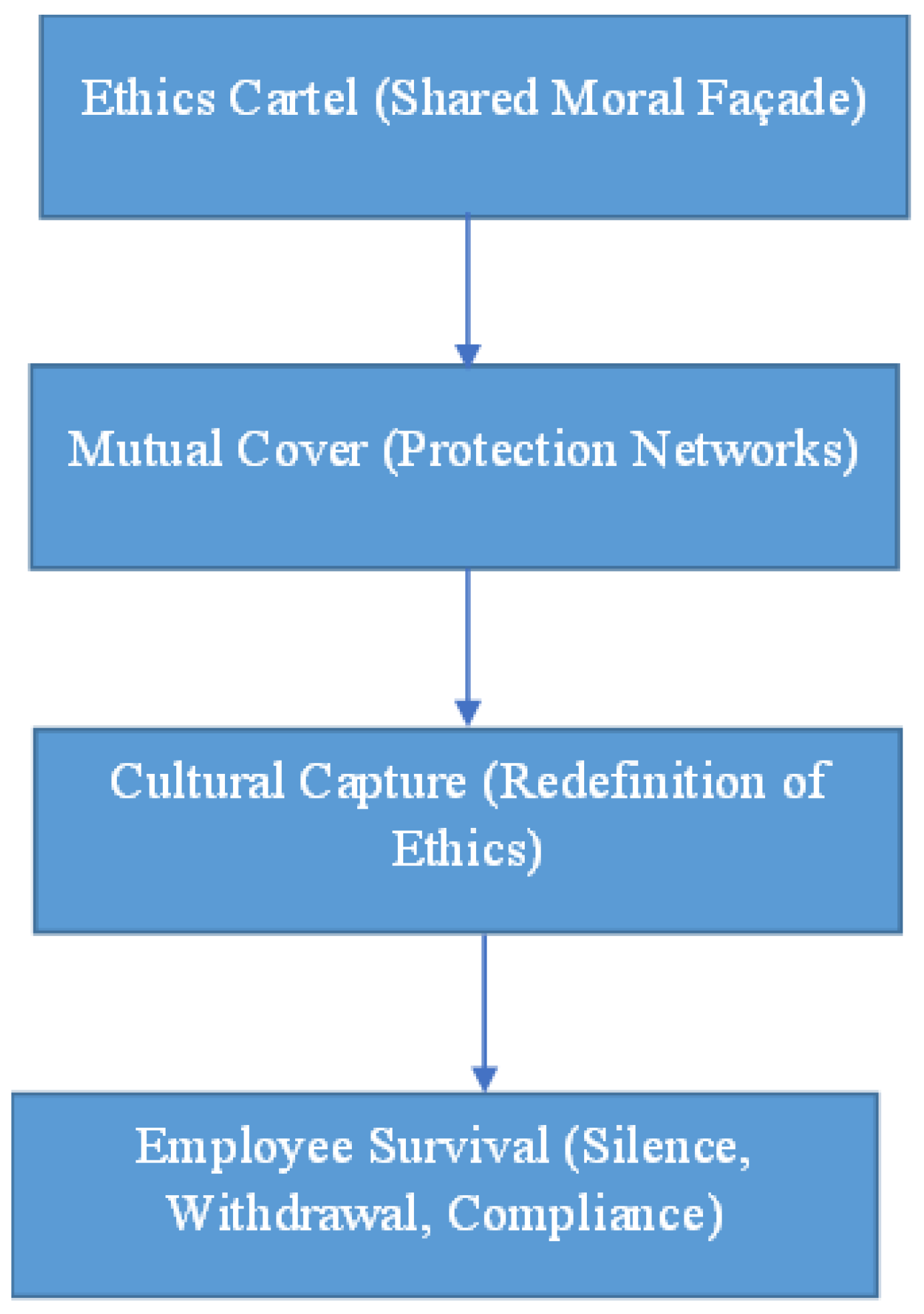

2.7. Conceptual Model

Figure 1 reveals that the theoretical frameworks situate toxic leadership at the intersection of three unexamined dimensions. Leaders are compelled by micro-level dark personality traits of psychopathy, narcissism, and Machiavellianism towards manipulativeness, irresponsiveness, and self-absorption. Dark personality traits are packaged in bundles. At the meso level, group leadership involvement in coalitions, poisonous work cultures, and “ethics mirages” enables abuse to accumulate in organizations so that unethical habits become second nature. At the macro level, organizational contexts, such as poor controls and regulative and cultural breakdown, create missive environments wherein abuse can be overlooked or left uncorrected. Given these extra dimensions, the model indicates that business scandals are not the result of single “bad apples” but are instead the result of synergistically compounding factors, group processes, and institutional weaknesses. Through this collaborative effort, research gaps are resolved, and a foundation is laid for an in-depth, holistic examination of corrosive leadership. Taken together, prior studies reveal both convergence, acknowledging the manipulative essence of dark traits, and divergence, regarding whether toxicity stems from personality or structural reinforcement. This tension underscores the need to study how dark traits become systemically embedded through collective reinforcement, a question left unanswered by existing research.

Each dimension of the framework maps directly to a research question:

RQ1—collective behavioral mechanisms (Ethics Cartel);

RQ2—discursive manipulation of ethics (Mutual Cover; Cultural Capture);

RQ3—organizational and employee outcomes (Employee Survival).

This alignment reinforces the internal logic of this study.

Traditional approaches to DT leadership focus primarily on individual actors; however, recent works by Alowais & Suliman [

1,

2] emphasizes that DT traits may be mirrored and reinforced across organizational levels. Their findings in higher education institutions reveal a bidirectional reinforcement loop between leader and employee DT traits, suggesting that toxicity spreads not merely from the top but evolves as a co-constructed system. This supports our conceptualization of

collective DT leadership as a synergistic dynamic, not simply a sum of individual pathologies. It is important to note the existence of the “ethics mirage” as an institutional phenomenon in which ethical behaviors are superficially enacted while enabling, or even concealing, ethically compromised leadership systems. Published works by Alowais & Suliman [

1,

2] describe how employees internalize and imitate dark traits through “toxic role modeling” and “shadow projection,” revealing how ethical frameworks can become simulacra—empty rituals performed to preserve reputational legitimacy. This reinforces the idea that collective DT leadership constructs a moral fade, sustaining unethical norms through mimetic and structural reinforcement. Due to this problematic phenomenon, this paper examines the systemic implications of coordinated Dark Triad leadership—particularly how these leaders do not merely disrupt ethical climates through individual misconduct but institutionalize unethical norms through mutual reinforcement and strategic moral façade construction. Drawing on works by Alowais & Suliman [

1,

2], who demonstrate the contagion effect of DT traits from leaders to followers, we argue that ethical decay in organizations is not a linear effect but a feedback-driven system in which power, personality, and culture are tightly coupled. The novelty of this conceptualization draws on works by Alowais & Suliman [

1,

2] to emphasize reciprocal learning loops between leaders and employees, where unethical behaviors are not only tolerated but mimicked and embedded. This expands the literature on moral disengagement and shadow leadership by illustrating how organizational ethics can evolve into self-sustaining systems of compliance and rationalization.

2.8. Literature Summary

This Section summarizes a critical review of the literature on destructive leadership, tracing its theoretical foundations, constructs, organizational outcomes, and real-world manifestations. The review demonstrates that while studies of the dark triad traits provide valuable insights into destructive behaviors, the evolution of research toward collective dark leadership frameworks offers a richer understanding of how power, deception, and governance failures coalesce into systemic misconduct.

Case studies such as Enron, Volkswagen, Theranos, Wells Fargo, and Uber show that destructive leadership transcends individuals, shaping organizational cultures and enabling large-scale corporate failures. However, collective dynamics, ethical fading mechanisms, and cross-contextual variations remain undertheorized.

The publications reviewed converge in their recognition that ethical infrastructures can be co-opted by powerful actors, yet none explain how this collaborative process unfolds. This gap directly informs the present study’s research questions, which examine the mechanisms and outcomes of coalition-based dark leadership. By addressing these gaps, this research also contributes to studies of leadership, organizational behavior, and corporate governance. It provides not only a theoretical framework but also practical implications for regulators, boards, and practitioners seeking to mitigate the risks of destructive leadership.

The literature leads to the perception that dark leadership traits are not simply imposed from above but often reproduced through mimicry and role adaptation among employees. This supports the notion that ethical deterioration is not an incidental outcome of poor leadership but is socially reinforced across hierarchical boundaries. The paper’s integration of Jungian shadow theory shows that employees unconsciously project and absorb the “dark selves” of their leaders, reinforcing an organizational climate where unethical conduct becomes normalized and routinized.

Much of the Dark Triad literature frames unethical behavior as a deviation from organizational norms; however, works by Alowais & Suliman [

1,

2] argue that in high-DT environments, these traits become part of the organizational grammar. Their evidence of strong correlations between leader and employee DT scores suggests that unethical behavior may be misrecognized as competence or normativity. This insight pushes beyond person-centric explanations and supports a systemic reading of ethical drift—where the misalignment between appearance and substance becomes embedded in the institution’s moral routines.

The concept of an “ethical climate” is often assumed to reflect a shared commitment to moral standards. However, the literature shows how such climates can be performative rather than substantive—functioning as reputational shields rather than internalized values. This reinforces our argument that collective DT leadership constructs an “ethics mirage”—an orchestrated illusion of virtue that serves to deflect scrutiny and suppress whistleblowing. The literature thus needs to move beyond ethical intent to examine the strategic deployment of ethics as a form of image management.

A critical contribution from this review is their modeling of feedback loops in the transmission of DT traits within organizations. By combining quantitative correlation data with qualitative narratives, they demonstrate how unethical norms can evolve from isolated incidents into institutionalized practices. This systemic framing strengthens the theoretical underpinnings of our argument: that collective Dark Triad leadership does not merely degrade ethics but actively reshapes organizational culture through cycles of modeling, reinforcement, and silent compliance.

3. Methodology

The methodological design reflects the Special Issue’s emphasis on rethinking how leadership research addresses power and performance. A qualitative, article-based document analysis of 55 peer-reviewed studies (2015–2025) was conducted to capture systemic rather than individual patterns. This method not only enables rigorous synthesis but also the identification of cross-cutting dynamics, such as collective accountability avoidance and cultural manipulation, that speak directly to the Special Issue’s focus on how leaders’ choices impact people and organizations. All 55 peer-reviewed articles were selected through a structured keyword-based search across Scopus and Web of Science using combinations of “Dark Triad,” “leadership,” “organizational ethics,” and “culture.” Inclusion required peer-reviewed status, relevance to workplace leadership or culture, and publication between 2015 and 2025. Thematic coding proceeded until saturation was reached, with themes triangulated across at least three distinct cases for conceptual robustness.

3.1. Design

This study utilized a qualitative interpretivist design suitable for the examination of intricate, socially constructed realities such as destructive leadership and corporate wrongdoing. In contrast to positivist paradigms that are measurement- and prediction-oriented, interpretivism recognizes that leadership dynamics revolve around cultural, ethical, and organizational contexts that cannot be measured in numerical quantities [

54]. By placing meaning and context sensitivity first, interpretivism allows for a deep analysis of how dark personality traits, group processes, and governance failures accumulate to foster unhealthy leadership.

The interpretivist stance is essential for capturing the meaning-making and sense-giving processes through which dark-trait leaders collectively rationalize unethical conduct. While quantitative approaches may measure the prevalence or correlation of Dark Triad traits, they cannot access the nuanced, discursive mechanisms by which these traits interact and manifest within organizational contexts. Interpretivism enables a contextualized understanding of how moral reasoning is reconstructed, legitimized, and socially negotiated among leaders operating within shared ethical façades.

As emphasized by Alowais & Suliman [

1], the relational influence between dark traits of leaders and employees is not merely behavioral but interpretive and embedded in narratives of justification, imitation, and moral normalization. Their findings underscore that dark leadership dynamics unfold as

lived social interactions, requiring methodological sensitivity to symbolic meaning rather than statistical generalization. Building on this epistemological foundation, this study adopts an interpretivist approach to uncover how “ethics” itself becomes a socially constructed mirage, which is a collectively sustained discourse through which toxic leaders confer legitimacy upon unethical actions.

This paradigm is therefore not only methodologically suitable but also philosophically coherent with the study’s aim to understand collective moral distortion as a human and linguistic construction. By interpreting organizational texts and discourses through an interpretivist lens, the analysis exposes how coalitions of Dark Triad leaders co-create a moral order that appears virtuous while serving as an instrument of power and control.

As an article-based document analysis, this study synthesized approximately 55–60 peer-reviewed articles published from 2015 to 2025. This window encapsulates both early work on the “Dark Triad” and later work on toxic leadership, business ethics, and governance failure. Document analysis is a systematic method of questioning knowledge that is available, forming thematic patterns, and synthesizing findings across disparate fields of study, such as management, psychology, sociology, and business governance. In particular, scrutinizing publications from peer-reviewed journals guarantees the infusion of systematically validated evidence without overemphasis on scholarly debate beyond practitioner remarks alone.

This approach is especially appropriate, given the fact that crippling leadership is often conceived piecemeal; at times, it is seen as a matter of personality, while other times, it is perceived as a matter of culture or structure. By systematically reviewing a large sample of the literature, this study bridges disciplines and generates an integrated conceptualization.

3.2. Sources of Data

Articles were identified using Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar with the keywords “Dark Triad leadership”, “toxic leadership AND ethics”, and “organizational culture AND moral disengagement”. Only peer-reviewed articles published in English (2015–2025) from Q1–Q3 journals were included. Non-empirical commentaries and conference papers were excluded. To mitigate bias, the articles were cross-validated by two independent reviewers and verified for disciplinary diversity (management, psychology, and ethics).

Although this study primarily employed an article-based document-analysis design, it also incorporated insights from case studies that were embedded within the reviewed journal articles. These case studies were not analyzed as independent field data but were treated as qualitative evidence contained in secondary sources. To clarify this scope, the inclusion criteria explicitly covered peer-reviewed empirical and theoretical works, including case-based investigations that addressed leadership ethics, organizational culture, and Dark Triad traits between 2015 and 2025. Each document was coded using the same thematic framework to ensure methodological consistency and comparability across formats. This clarification aligns the methodology with the content of the literature review and eliminates any perceived inconsistency. Primary sources were peer-reviewed journal articles that were handpicked from top databases like Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar. The inclusion criteria in terms of relevance and quality were as follows:

The research should have a specific emphasis on destructive leadership, dark traits, toxic workplaces, or corporate malfeasance.

Books should have publication dates between 2015 and 2025 to provide contemporary relevance while including seminal works.

Sources must be peer-reviewed journal papers, systematic reviews, or book chapters from important academic presses.

Gray literature, such as consultancy reports and journalism articles, is excluded on methodological grounds, but significant corporate scandals (e.g., Enron, Volkswagen Dieselgate, Theranos) are used illustratively throughout the analysis.

This set offered a corpus of roughly 55–60 cases bridging organizational behavior, psychology, ethics, and corporate governance. The number of cases is reasonable on grounds of saturation beyond this point; additional articles would not add new conceptual content but would repeat themes.

3.3. Analytical Strategy

Thematic analysis was facilitated by the Gioia methodology [

55]. This approach provides flexibility and systematic rigor in the identification, organization, and interpretation of textual data patterns. The Gioia methodology offers systematic coding with a cross-process spanning raw information from the literature to higher-order theoretical concepts.

Three iterative steps comprised the process:

First-Order Coding (Informant Centric): Quoted words and phrases and conclusions were taken from the articles without any external interpretation. For instance, words such as “leader narcissism breeds unethical risk-taking” or “subordinates keep silent in the presence of toxic leaders” were coded in vivo.

Second-Order Coding (Researcher Centric): Consistent first-order codes were grouped into conceptual themes, i.e., “moral façade,” “mutual protection,” or “compliance through fear.”

Aggregate Dimensions: Second-order themes were synthesized into higher-level constructs that identified the multi-level dynamics of toxic leadership. They were equal in number to the priori sensitizing concepts, providing a prefatory point of reference without excluding emergent insights.

The last thematic structure wove empirical voice with theoretical abstraction to produce a rich description of how individual nature, collective process, and systemic management converge within toxic leadership.

3.4. A Priori Theme Sensitizers

In structuring the analysis, four sensitizing concepts were adopted from the emergent literature review. These were not hypotheses; rather, they were conceptual pointers that guided the coding framework.

Ethics Cartel explains how organizations build a moral front through which to politically enforce ethical conformity and dissembled it from practice [

11]. Scandalized companies, for example, will highlight ethics codes or green reports to cover up ongoing malpractice.

Mutual Cover describes ad hoc protection networks between leadership groups in which players collude to cover each other from monitoring. In this way, corrupt leaders are shielded by their cohort and will not be singled out.

Cultural Capture represents a situation in which ethics are re-framed in language that benefits the leaders’ interests and not organizational integrity. This is an expression of manipulation and deviance normalization.

Employee Survival explains how employees, experiencing coercion, fear, or hopelessness, use strategies of silence, compliance, or disengagement. These adaptive responses are the reason toxic leadership is so pervasive in the context of apparent damage.

By blending deductive sensitization with inductive discovery, this analysis balances theoretical focus with empirical receptiveness.

3.5. Ensuring Methodological Rigor

Qualitative research is often criticized based on its subjectivity. To counteract this, several rigor-enhancing strategies were incorporated into this study:

Triangulation: Searches were conducted across a range of journals and disciplines to avoid reliance on one corpus of literature [

56]. This ensured the results were unbiased in terms of discipline.

Reflexive Memoing: While coding, reflective memos were maintained in situ to track analysis decisions and avoid researcher bias [

57].

Audit Trail: A systematic record of article selection, coding, and theme emergence was retained for transparency and replicability [

58].

Peer Debriefing: Interim findings were double-checked against existing theoretical frameworks to verify conclusions against existing scholarship. These practices support credibility, task dependability, and confirmability, supporting the methodological rigor of this study.

3.6. Ethical Considerations

While this study was not conducted on human subjects, ethical issues remain significant. Intellectual property is maintained by proper citation and referencing. This study also avoids the denationalization of company mistakes; cases such as Enron, Theranos, and Volkswagen’s Dieselgate are used only to the extent they are useful in illustrating theoretical principles but not to assign blame to specific individuals. Through this research methodology, scholarly integrity and principles of ethical research are upheld.

3.7. Methodological Limitations

As with any study, this research has some limitations. First, the use of secondary data limits the analysis to the data and literature currently available. Second, while interpretivism does yield a rich understanding of context, it precludes causal statements or generalizable statistical inference. Third, thematic coding subjectivity leaves an opportunity for bias, although this risk is mitigated by triangulation and reflexivity.

These constraints are offset by a strict approach to the convergence of deep disciplinarily knowledge and yielding a generic conceptualization of destructive leadership.

3.8. Methodological Summary

This chapter has defined the research approach. A qualitative interpretivist research design, rooted in article-based document analysis of 55–60 peer-reviewed articles, permits a rich examination of destructive leadership. Through a thematic analysis with Gioia coding, this research makes use of a priori sensitizing concepts and emergent patterns to develop a robust conceptual model. Rigor is established through triangulation, reflexivity, and audit trails. Ethical matters and limitations are also considered. By aligning the individual, collective, and system levels of analysis, this approach lays the groundwork for the subsequent chapter on findings, in which coded themes are explained and traced back to the conceptual model.

4. Findings

The findings of this study as shown in

Figure 2 reveal three dynamics that resonate with the Special Issue’s theme. The

Ethics Cartel illustrates how coalitions reconstruct power under the guise of moral leadership, sheltering wrongdoing and reinforcing dominance.

Mutual cover demonstrates the relational impact on people, where accountability is eroded and employees are left vulnerable to systemic abuse. Finally,

Cultural Capture describes the degradation of performance as organizational culture is reconfigured to normalize manipulation rather than excellence. These patterns underscore the importance of rethinking leadership not as an individual quality but as a collective system with cascading consequences. This section also provides a thematic analysis of the review articles, clustering findings regarding the phenomenon of collective dark leadership. Although most of the literature available discusses the dark impact of individual Dark Triad (DT) leaders [

13], comparatively fewer inquiries investigate whether such leaders exist in collusive sets or webs of webs. There are four interconnected themes in the current research: (1) Ethics Cartel, (2) Mutual Cover, (3) Cultural Capture, and (4) Employee Survival. Together, these themes describe the ways dark leaders synchronize to practice symbolic ethics manipulation, protect each other, reconstruct cultural norms, and promote adaptive silence among employees, thus solidifying toxic systems.

After extracting first-order expressions from the reviewed texts, the coding process followed the Gioia methodology to ensure conceptual rigor and transparency. Initially, salient in-text phrases such as “protect each other’s image” and “rebrand unethical acts as loyalty” were identified as first-order codes, capturing the language used by the original authors. These codes were then grouped into second-order themes that represented broader conceptual patterns, such as Mutual Protection Norms, Ethical Reframing, and Cultural Domestication. Finally, these themes were collapsed into aggregate dimensions—Mutual Cover, Ethics Cartel, and Cultural Capture—that constitute the core mechanisms of collective Dark Triad leadership. This iterative process allowed the analysis to move from descriptive observations to theoretically grounded categories, linking micro-level expressions to systemic meso-level processes.

4.1. Theme 1: Ethics Cartel—Coordinated Value Talks, Ethics Programs, and CSR Signaling

Kador [

28] sees ethical leadership as a practice comprising moral role-modeling, fair dealing, and care for followers. In dark leadership, the model is reversed. These narcissistic, Machiavellian, or psychopathic high-scoring leaders employ a pretense of ethical rigor in the form of CSR programs, value statements, ethics programs, and codes of ethics [

10]. Rather than constraining wrongdoing, these symbolic frameworks are a “legitimacy shield.” Cerne [

59] describes this practice as the decoupling of formal symbolic commitments and material action. Nitschke’s organizational theory frame of ceremonial compliance [

11] demonstrates how such ethics programs are predominantly implemented as rituals to obtain external legitimacy but remain exploitative.

This analysis shows that when dark leaders collude, these symbolic instruments integrate into what can be called an Ethics Cartel. Similarly to how a market cartel promotes price conformity to lock in collusion, an Ethics Cartel conformity enables “value talks” between leaders to create an external collective ethical veneer. For example, different case studies presented in the literature provide examples of teams of corporate executives who endorsed sustainability projects while engaging in cost-reduction strategies that impacted employee welfare [

10].

Paradoxically, the institutionalization of ethics can be employed to conceal unethical acts. Taddeo [

60] argues that ethics programs, if they are intended to be showcased, can conceal wrongdoing by highlighting preset symbols of legitimacy, like ethics training programs, CSR publications, and compliance rates, that are generally interpreted by regulators, investors, and stakeholders as symbols of integrity. The cartel effect is that such signaling is of an organized nature: groups of dark leaders use indoctrination on congruence in values communication, not for the purpose of enabling true ethics, but to organize manipulation tactics.

Theoretically, this issue is a reversal of Kadir’s ethical leadership model [

28]. Rather than modeling integrity, the dark leaders engaging in strategic moral posturing. Instead of true fairness, they institutionalize performative fairness, guaranteeing that salient procedures are put in place while outcomes remain biased. Rather than promoting follower well-being, they distribute resources to CSR branding, thereby building reputational capital without repairing internal harm. It is not hypocrisy; rather, it is the institutionalized symbolism of solidarity ethics, using language around ethical values as a mechanism for internal control and external display. This is the foundation of the second theme: Mutual Cover. For instance, senior management coalitions that jointly sanitize misconduct through shared codes of loyalty and rhetorical moralization are a clear example of the

Ethics Cartel dynamic. The leaders co-create narratives of “ethical responsibility” to legitimize actions that serve their collective interests, exemplifying how moral discourse is weaponized to mask collusive intent.

4.2. Theme 2: Mutual Cover—Covering Up Through Hiring, Appraisal, and Investigations

Chen’s Toxic Triangle model [

15] posits that toxic leaders thrive when susceptible followers and enabling environments facilitate abuse. Although there has been significant research conducted with follower vulnerability surveys, the existing findings highlight the manner in which leaders actively create safe climates through the creation of collusion networks. Alexander et al. [

30] demonstrate how abusive leaders sustain power through their application of coalitions that take over rightful processes, i.e., recruitment, promotion, and performance appraisal, to strengthen their own legitimacy. Yang et al. [

61] build on this analysis through the theory of bounded ethicality: individuals can justify unethical acts as acceptable within situational boundaries. When applied to a sample of dark leaders, bounded ethicality translates into Mutual Cover, as the leaders justify each other’s suspicious actions by contextualizing them within organizational routines.

The literature recognizes three primary mechanisms of Mutual Cover:

Promotion and recruitment: High-DT leaders preferentially promote or recruit those who share a common set of values or loyalty to them, thereby creating guardian networks [

15]. This creates what Kathmandu [

62] described as moral mazes: bureaucratic structures in which responsibility is scattered, and promotion hinges more on loyalty than integrity.

Measurement of performance: Mutual coverage is also applied to performance metrics, which are secretly manipulated to legitimize otherwise ethically questionable activities. An example is short-term profitability, which can lend legitimacy to compromising practices or exploitation that the leaders subsequently cover up as “performance excellence” [

30].

Investigations and compliance procedures: Collective alliance leadership can deflect internal investigations through inundating investigation teams or delivering results in ways that downplay blame. This causes compliance models to function as instruments of exoneration rather than responsibility [

59].

Mutual Cover suggests that collusive leadership networks leverage organizational architecture itself. While the Ethics Cartel operates symbolically (Theme 1), Mutual Cover operates structurally, weaving protection into HR, audit, and assessment processes. Together, these strategies provide cover that makes it very difficult for individual missteps to be criticized or punished.

In the real world, practicing Mutual Cover can transform the Toxic Triangle into a poisonous web. Instead of one destructive leader preying on an enabled environment, multiple leaders enable one another, producing a system in which accountability is inverted. Evidence of the

Mutual Cover mechanism is provided in empirical studies of executives who collectively neutralize accountability by reframing concealment as solidarity. Nguyen et al. [

23] found that top management teams engaged in reciprocal protection pacts that blurred individual culpability. Similarly, Boddy [

19] observed leaders in corporate scandals who shielded one another from exposure, constructing a closed circle of mutual immunity. This finding leads us straight into Theme 3: Cultural Capture.

4.3. Theme 3: Cultural Capture—Redefining Ethics to Normalize UPB

While Themes 1 and 2 stress symbolic and structural manipulation, Theme 3 is concerned with a more insidious process: the reconstruction of organizational ethics itself. Manelkar & Mishra [

63] provides the concept of unethical pro-organizational behavior (UPB), through which employees justify unethical conduct as indispensable to organizational success. Sanni [