1. Introduction

The Training for Sustainable Employment of Youth and Young Adults Project (TSEMY) was set up by a consortium of organisations in six countries: five EU member states, Portugal, Italy, Romania, the Czech Republic, and Spain, and an EU candidate, Turkey.

This project addressed a recent urgent and important topic: increasing unemployment in the young population, especially for those with at least post-secondary and higher education levels. A generation ago, similar projects with the objective of reducing unemployment were designed for low-qualified young people. Then, one of the main solutions prescribed was to increase the group’s human capital with the strategy of increasing the education level.

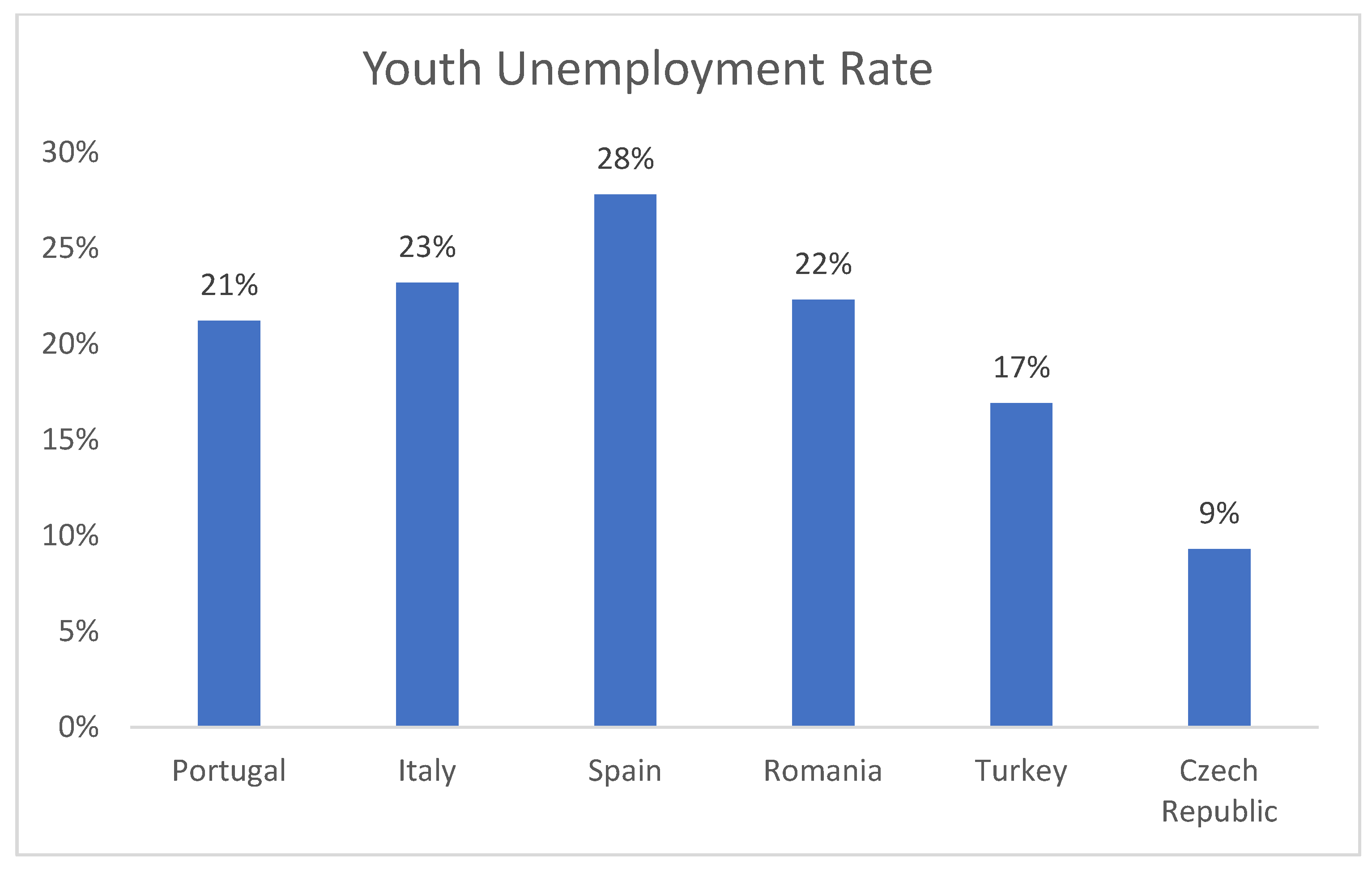

However, youth unemployment is still considered a widespread problem throughout Europe. The data for the countries participating in this study can be seen in

Figure 1.

As we can see, youth unemployment rates in these countries are between 9% and 28%, with four of the six participating countries above 20%. These results emphasise the relevance of the project’s orientation towards understanding and analysing guidelines to promote training for the increased sustainable employment of young people.

Currently, unemployment has become an issue among those who have obtained higher educational qualifications. In the search for new solutions to the problem of unemployment among young people, one of the reasons identified as being responsible for this phenomenon relates to the gap between the training received and the needs of employers. Accordingly, this project was designed for higher education graduates and intended to involve not only the job seekers but also to identify employer practices, not only as part of the problem but also as the key to the solution.

Unemployment in society, creating an impact across the countries of the European Union, with the various problems inherent to the difficulty of entering and remaining in the labour market, has increased the need for initiatives aimed at orienting, advising, preparing, and training the population in this precarious and socially vulnerable situation [

1].

Therefore, in the first step of the project’s development, each partner country reviewed the national situation and produced a report with respect to the following points: a brief description of the country’s general situation concerning the integration of young people in the workplace; an overview of the current legislation that included a description of any national/regional legislation relating to the integration of young people with higher education in the workplace; a description of policies and practices (including policies either in place or in process in the country); a description of services that specifically relate to young people; an overview of the training opportunities initiated by companies and recruitment organisations; an overview of guidance/training courses for companies/stakeholders on the application of regulations and the integration of young people into employment; resources allocated for training; a description of best practice samples (an overview of good projects, campaigns, institutions, and public structures concerned with the integration of young people at a local, regional, national, and European level; the identification and description of skills and competencies that are covered by these good practices; the identification and description of the skills and competencies that are not covered and are needed); the profile of professionals (brief description of educational background) and the professions of specialists working with young people with higher education; a description of the skills they have been provided with through their acquired education; a short description of any subject/course/module in their education curriculum aimed specifically at working with the integration of young people; the skills that are provided through completing these courses.

According to the main conclusions of these national reports, youth unemployment is a transversal reality for each European partner, and national efforts to ameliorate this social situation are oriented towards the creation of opportunities for young people. The training and apprenticeship contract is one of the most important and specific means of accessing employment for young people. The aim of the contract is to promote learning in the work environment and the acquisition of transversal professional skills during the training period. Adapting the specialisations of the educational system to the requirements of the labour market is also an important step in facilitating the accommodation of young people in employment. Therefore, the development of a specific training programme seems to be an important factor in this process, combining know-how and skills that employers will value.

Best practice research in each partner country revealed a wide range of competencies. However, in the current social context and after the impact of a pandemic, others have emerged as necessary, for example, innovation and creativity, meaning the ability to search for solutions, to detect changes, and to see opportunities; communication skills; time management, meaning the ability to prioritise the most urgent and important tasks over others so that the day is more productive; proactivity; the ability to solve problems and be agile in the decision-making process; and adaptability and flexibility.

Regarding these national scenarios, specifically analysed by each partner included in the project, the question for our research was: what are the training needs of youth and young adults to attain sustainable employment?

2. Theory and Literature Review

In this section, we conduct a review of the literature supporting and analysing the phenomenon related to management styles as well as cultural aspects.

In this respect, we observe the natural development of the contracting values model. We consider its initial form until its transition from the normal state to the fundamental state of leadership, including behavioural considerations [

2].

Later, we attempt to frame the behavioural aspects with the evolution of management models in historical terms, reserving for the end of this section a connection of concepts through the notion of value creation in organisations [

3].

2.1. The Specific Context in the Training Sector

According to Ribeiro [

4], the second law of thermodynamics, and complexity theorists, all systems tend to create entropy. Entropy is a measure of malfunction or a measure of the energy of a system that does not produce in accordance with the resources used. In essence, entropy tends to close a system; then, the entire closed system stops functioning properly. The principle would not only apply to physical systems but also to interactions between individuals and to the organisations, resulting from those interactions [

3].

The general tendency is that people and organisations make progress and then stagnate. At first, that period of stagnation can help individuals or organisation consolidate and recover. Then, the period risks changing into a comfort zone that is equivalent to a phase of stabilization and consolidation in which control of the situation seems to satisfy the manager: they know how to manage; how to do the things they need to do; routines are established; and if nothing changes, the leader may even be successful [

5].

However, the universe is a system in constant change, from which signals are received, creating alerts for the need for growth and elevation of action beyond routines, and to advance to higher levels of complexity. Initially, everyone tries to ignore these signs. Normally, it is not when the initial warnings sound that people are willing to significantly change the way projects are carried out [

6].

When employees are not aware of the critical aspects surrounding organisations, they may only realise that they are living in a comfort zone when they receive a surprise external message. In this context, the tendency is to increase routine tasks, i.e., those that they know how to perform [

6].

According to Rego and Cunha [

7], the description of organisations at that time has only a little to do with people’s state of mind; that is, people are more interested in their own activities, the organisation does not have a common objective, and the operational strategy must respond to the personal agendas of important people [

8].

This description reflects normal conditions in organisations. Descriptions of the conditions can usually be found in specialty reports and academic investigations. With individuals within the organisation exhibiting only self-interest, with no desire to change, and no signs of excellence, these situations are so common that they have even become expected and accepted (Cunha et al. [

9]).

In these types of organisations, it is not possible to observe someone with a desire to achieve excellence. People become complacent and seem to prefer not to take on personal responsibility and coherence anymore [

8].

At this stage of the so-called normal, or routine, state, the need for profound change is not immediately understood. However, missing opportunities for change is something that can bring about the end when the organisation fails to respond to the signals that arrive from the environment. Increasingly closed, both energy and hope are lost in the system. Individuals experience negative emotions such as fear, insecurity, and doubts, and the leadership fails to respond to signals sent from external reality and the surroundings [

3].

As the organisation becomes increasingly switched off, even more energy is lost, and it ends up being trapped in a vicious cycle. At the same time, vitality is lost. The individual works to remain in their own comfort zone. However, in this way, one can only imitate what has been achieved or performed in the past, failing to integrate the emerging realities of the present [

10].

It is normal to be focused on comfort. Many leaders prefer to live within a predictable culture. In doing so, they develop an ego that helps them survive. When the culture is stable, people usually tend to live in a reasonable comfort zone [

11,

12].

Additionally, in this situation, people know what they need to know. If there are signs of the need for change, one may have to face processes of uncertainty and learning new things. This will be perceived as a threat to the ego; as a result, the threat tends to create negative emotions. Is the need for change a problem that needs to be solved? The solution appears to require both a reaction and an attempt to maintain balance, as in a normal situation [

3].

2.2. Applied Model for the Development of a Training Programme

According to Quinn and Thakor [

3], management models have evolved throughout the history of management, in line with the various quadrants described in their model of contrasting values.

The authors state that in the time of the management expert Taylor (1900–1925), action was more centred on the model of rational objectives. In the period led by the experts Fayol and Weber, between 1926 and 1950, action became centred on internal processes. Between 1950 and 1975 was the time of significant use of models focused on human relations. Finally, the open systems model emerged after 1975 and focused on moderation and innovation actions [

3].

However, from 1976 to today, we also observe a convergence of the various models, creating pressure and tension between them, which can be measured through the four quadrants that are illustrated in the model of contrasting values [

3].

This tension and pressure can be measured through the decision-making process, in which intra-personal conflicts are generated. They arise, according to Quinn and Thakor [

3], from the conception of organisational conflicts [

13], generated whenever an organisation works and acts according to the objectives and direction of another (normally in multinational companies).

According to Robbins et al. [

13], there are three fundamental types of intra-personal conflicts: when choosing between two actions or two results, when there are both positive and negative aspects in the options taken, or when there are two negative options.

Conflicts can certainly arise as the result of the decision-making process in all organisations, which could have different solutions, whether multinational companies or local organisations [

14].

2.3. Leadership for Training

At this point, using the model of competing values once again, we study how the exercise of leadership, in its various aspects, can lead to the creation of value in organisations.

The performance of leaders is analysed here from a new perspective, which, according to Cameron and Quinn [

14], can be described as follows:

This aspect of the model, focused on leadership, will be in constant tension through the balance between the various forms of action, that is, an action that is more like teamwork (collaboration), an action of control, of creating things, or also of competitiveness (speed).

All actions function through the people, practices, and purposes with which they work.

This link that is established between the two currents (leadership/value creation) in effective organisational performance is of high interest because strong links are then established between the concepts of the fundamental state of leadership that Cameron and Quinn [

14] relate to the reduction in waste in organisational processes as well as the contribution to increases in productivity and quality.

In our study, it can be considered that the group of managers in national companies tends to be less focused on creating value since they focus on internal processes and the normal state of leadership. Meanwhile, the group of managers within multinational companies can be considered more focused on creating value through rational objectives and the fundamental state of leadership. Furthermore, they can become more balanced through the external relationships of the hierarchy, forcing them to become more flexible [

3].

2.4. Trainers and Trainees Create Culture

The actions of leaders will condition their performance and their effectiveness in achieving the creation of value, both in terms of financial and human capital.

At this point, some approaches to leadership behaviour associated with organisational culture should be considered. These include the behaviour of leaders, which should be characterised, according to Quinn and Thakor [

3], according to the following aspects: openness, integrity, humility, good vision of the present and the future, an optimistic outlook, appropriate use of authority, and a strong understanding of personal and organisational goals. Without all these, the leader is a leader in designation only and not in behaviour and attitude.

The ideas of Quinn and Thakor [

3] can be summarised as recognising that followers assume a line of behaviour that emulates that of leaders; therefore, this guarantees the development of subordinates through training and development of their skills—representing positivist logic.

According to Drucker’s vision [

15], leaders who follow this style only accept people with their own characteristics into the organisation, who do not contradict them and without new forms of vision and ideas, blocking organisational culture and future development but having some immediate operational results—representing negativist logic [

16].

Typically, these approaches consider the internal aspects of the organisation, such as the behaviour of leaders and managers; however, the idea of entities external to the organisations will always be important [

17].

A question raised by Quinn and Thakor [

3] that is related to the differences between internal and external perspectives refers to the way in which the context and the environment surrounding the organisation should be understood, together with how one’s actions adjust to the external environment—representing an open systems model with strong development [

18].

From the research point of view, Goleman et al. [

19] emphasised that internal agents tend to be more in agreement with the analyst or researcher in that they are visible, communicate internally, use a common language (according to Robbins [

20]), and are willing to cooperate because they know the object of the study.

External agents are more difficult to analyse, and there are other types of concerns that will cause the dispersion of ideas and conclusions [

21].

According to Robbins et al. [

13], the thesis defended by the authors is close to the position of R. Quinn and leads to the classification of a type of organisation called externally controlled, which in turn will give rise to three different characteristics for training the management functions: symbolic, reactive, and discretionary [

22,

23].

- -

Symbolic—actions are not related to concerns and constraints and have little effect on management.

- -

Reactive—actions are completed in relation to the needs and concerns of the surrounding environment.

- -

Discretionary—concerns and the environment are managed in favour of the organisation’s interests, seeking to create the most favourable context.

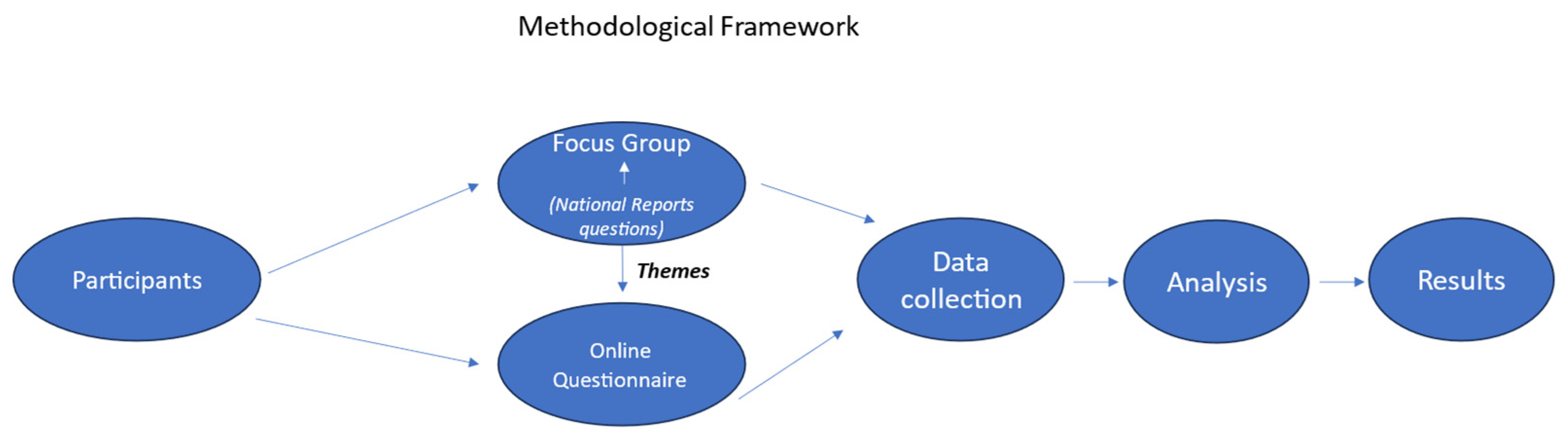

In line with these theoretical concepts and considering the aim of this study, a research design was devised combining two types of data collection instruments: a focus group (with exploratory questions emerging from national reports) and a questionnaire (with themes constructed from the data emerging from the focus group).

3. Method

As this study was based on a project report, we supported our scientific analysis methodology using the scheme presented in

Figure 2, which aims to consolidate the sequence of actions for applying the instruments and the corresponding analysis of the results.

We thus segmented the participants to be selected by different events, such as the use of focus group instruments and the application of questionnaires, as detailed below. As a result, the application of the methodology is a qualitative method confirmed by statistical elements and clustering for confirmation of the ideas raised.

3.1. Participants

The main conclusions of the national reports highlighted the main actors in employment and unemployment issues. This allowed us to identify the target groups as mentors/tutors; last year’s university students; unemployed graduates; companies and recruiting entities from various areas of activity; leaders/representatives of local communities; services and entities acting in terms of employment, capitation, and professional integration; representatives and actors in the labour sector; trainers, teaching/training, and personal development professionals. The focus group participants were selected in these target groups, with a total of 144 participants, divided into 4 groups (see

Table 1).

Group 1 included university personnel, such as professors and directors. Group 2 included managers or experts in the market sector. Group 3 included public and private market sector professionals and technicians, and Group 4 included unemployed students and last year’s university students aged 20–29 years old.

The selection of participants for the questionnaire was derived from the themes that emerged from the focus groups that emphasised the perception and experience related to the process of training and learning needs for young people. The total number of participants was 244, divided into a sample of students and young graduates (n = 108) and a sample of teachers (n = 136).

In the sample of students and young graduates, the number of participants was divided into countries (PT: 26; SP: 21; CZ: 15; IT: 15; RO: 16; TUR: 15). A total of 90 participants were students, and 18 were not (young graduates). In total, the sample of students and young graduates was very similar in terms of sex (M = 49; W = 58; Other:1), and the mean age was 25 years old. In all, 68 participants were looking for a job, and 40 were not. Except for one participant, all were nationals of the country in which the data were collected.

In the sample of teachers, the number of participants was divided into countries (PT: 43; SP: 29; CZ: 15; IT: 15; RO: 16; TUR: 18). In total, the teachers had a higher number of women (M = 47; W = 88; Other: 1), equivalent to 64.7%, and the mean age was 44.2 years old. All participants were nationals of the country in which the data were collected.

3.2. Instruments

3.2.1. Focus Group Questions

An online focus group is a method of data collection that enables the researcher to host a discussion between several respondents through an online platform. The typical duration of a focus group ranges from a minimum of 60 min to a maximum of 120 min. The main questions raised were: (1) What problems, barriers, or gaps exist in the professional integration process of young people? (2) What is the best and most needed training to support the sustainable employment of youth and young adults? (3) What themes, topics, content, and arguments should this training contain?

3.2.2. Online Questionnaire

The questionnaire had two versions: version A was designed to collect data from the sample of students and young graduates, and version B was designed to collect data from the sample of teachers.

The student and young graduates’ version (version A) included a first section with sociodemographic questions to characterise the sample: sex, age, student or not, looking for a job or not, nationality. Section 2 was designed to evaluate how useful students and young graduates thought it would be, in their personal training, to deepen all or any of the following list of topics: (1) skills improvement (strategic and organisational skills, problem solving, and decision-making); (2) personal brand (strategies to promote yourself, your skills and experiences, and your career); (3) good and bad communication (effective communication, building great teams); (4) innovation and creativity (digital solutions to enrich skills and competencies, proactivity, turning ideas into products); (5) entrepreneurship (identification of business opportunities, markets, and the search for needs and planning); (6) issues inherent to diversity/inclusion/gender equality; (7) globalisation: international orientation.

Section 3 was designed to discover whether the students and young graduates thought it could be useful to learn more about the following skills and competencies: (1) strategic and organisational skills (soft, digital, personal); (2) personal training on time management; (3) negotiation, problem solving, and decision making; (4) how to identify your goals and act accordingly; (5) refining of your personal brand and skills and staying ahead of the competition; (6) job search strategies; (7) effective communication; (8) the role of listening in communication; (9) building great teams; (10) intercultural and social communication; (11) dealing with the “me” and the “others”; (12) new media and social networks; (13) digital solutions to enrich skills and competencies; (14) proactivity; (15) gamification; (16) self-learning; (17) introduction to entrepreneurship; (18) identification of business opportunities. Section 4 asked what type of training methods students and young graduates considered might be most suitable for the delivery of their training: (1) project-based learning; (2) service learning; (3) self-study; (4) active learning methodologies; (5) gamification; (6) blended learning; (7) distance learning. Section 5 asked students and young graduates to identify which devices they preferred to adopt or use during training: (1) portable; (2) tablet; (3); mobile phone. The questions in Sections 2–5 were presented on a Likert scale, ranging from less useful (1) to more useful (5).

Version B was directed at teachers. This version for teachers included an initial section with sociodemographic questions: sex, age, and nationality. Section 2 was designed to evaluate how useful teachers thought it would be to deepen all or any of the following topics in their personal training or teaching: (1) skills improvement; (2) personal brand; (3) good and bad communication; (4) innovation and creativity; (5) entrepreneurship; (6) issues inherent to diversity/inclusion/gender equality; (7) globalisation: international orientation.

Section 3 was designed to discover whether the teachers thought it could be useful to learn more about the following skills and competencies: (1) strategic and organisational skills (soft, digital, and personal); (2). personal training on time management; (3) negotiation, problem solving, and decision making; (4) how to identify your goals and act accordingly; (5) refine your personal brand and skills and stay ahead of the competition; (6) job search strategies; (7) effective communication; (8) the role of listening in communication; (9) building great teams; (10) intercultural and social communication; (11) dealing with the “me” and the “others”; (12) new media and social networks; (13) digital solutions to enrich skills and competencies; (14) proactivity; (15) gamification; (16) self-learning; (17) introduction to entrepreneurship; (18) identification of business opportunities. Section 4 asked what kind of training methods teachers thought would be most suitable for their training: (1) project-based learning; (2) service learning; (3) self-study; (4) active learning methodologies; (5) gamification; (6) blended learning; (7) distance learning. Section 5 asked teachers to identify which devices they preferred to adopt or use during training: (1) portable; (2) tablet; (3); mobile phone. The questions in Sections 2–5 were presented on a Likert scale, ranging from less useful (1) to more useful (5).

3.3. Data Collection Procedures

Data were collected through the recommendations and advice provided by the online focus groups and the information collected through the online questionnaire. According to a shared methodology, the focus group was conducted with operators and stakeholders, aimed at further discussing problems, barriers, and gaps in the job placement process, current training on offer, and training needs for youth and young adults, together with possible solutions. Each partner used the same interview guide for the focus group. Therefore, each partner organisation had planned and developed four focus groups through an online platform due to the COVID-19 restrictions, with a total of 144 participants.

The data were also collected through an online questionnaire shared by the partners. This instrument was constructed to analyse the operators’ training needs (teachers, students/young graduates) and to collect information on their perceptions and experiences related to the training and learning needs of young people. Each partner delivered the same questionnaire, translated into the national language, to a convenience sample in each country. The questionnaire was disseminated via email or social media and addressed to the specific target group of students/young graduates and teachers, mainly exploring the existing networks of each partner.

3.4. Data Analysis Procedures

Data collected from the focus group were categorized using content analysis [

24].

Data collected from the online questionnaire were analysed using statistical software, SPSS 28. Means and standard deviations are presented in the results.

4. Results

The answers to the questions and themes addressed by the focus groups enabled the identification of the categories that were specified in the data collection through the questionnaires. Therefore, the results of these data are presented below according to the following categories: topics to deepen via personal training; skills and competencies that could be useful to learn more about; most suitable training methods; device(s) for training.

4.1. Topics to Deepen via Personal Training

The data collected from the questionnaires in the two samples (students and young graduates; teachers) are presented in

Table 2 and

Table 3 below with means and standard deviation values. The topics to deepen via personal training or teaching are presented in

Table 2.

In general, the results indicated that students/young graduates and teachers considered these six topics useful either for personal training or teaching. The opinions of students/young graduates’ about skills improvement (M = 4.32) and personal brand (M = 4.31) were selected as the most useful topics to deepen via personal training, followed by good/bad communication (M = 4.16) and innovation/creativity (M = 4.15). Teachers considered skills improvement (M = 4.38) and innovation/creativity (M = 4.38) as the most useful topics, followed by good/bad communication (M = 4.30) and personal brand (M = 4.30).

To understand how the variables were supported by practical skills, we attempted to understand whether there was any relationship between these and the acquisition of new skills; thus, we obtained the following analysis, which allowed us to understand the phenomenon, through the two fundamental clusters of students and teachers.

Clustering, or data grouping analysis, is a set of data prospecting techniques that aim to automatically group data according to their degree of similarity.

Cluster analysis is a statistical method for processing data; it works by organising items into groups or clusters, based on how closely associated they are.

Convergence was achieved due to no or small changes in the cluster centres. The maximum absolute coordinate shift for any centre was 0.000. The current iteration was 1. The minimum distance between the initial centres was 0.384.

4.2. Useful Skills and Competencies to Learn

The results concerning the skills and competencies that could be useful to learn more about are presented in

Table 4.

Students/young graduates considered a wide range of skills more useful for learning in the following order: effective communication (M = 4.44); negotiation/problem solving/decision making (M = 4.39); identification of goals and acting accordingly (M = 4.32); listening in communication (M = 4.28); self-learning (M = 4.21); strategic and organisational skills (M = 4.20); personal training on time management (M = 4.12); intercultural/social communication (M = 4.12); identification of business opportunities (M = 4.11); and proactivity (M = 4.10).

Teachers also considered a wide range of skills more useful for learning in the following order: strategic and organisational skills (M = 4.29); effective communication (M = 4.26); digital solutions to enrich skills (M = 4.18); self-learning (M = 4.15); proactivity (M = 4.14); negotiation/problem solving/decision making (M = 4.13); identification of goals and acting accordingly (M = 4.12); and listening in communication (M = 4.12).

4.3. Most Suitable Training Methods

The results concerning the types of training methods most suitable for training are presented in

Table 5.

Project-based learning and active learning methodologies were considered the most appreciated by students/young graduates (M = 4.29; M = 4.13) and teachers (M = 4.37; M = 4.33).

4.4. Device for Training

The results concerning which device was considered more useful for training are presented in

Table 6.

Laptops were chosen by both students/young graduates and teachers as the best device to use in the training activities (M = 4.65; M = 4.60).

The results of the project did not include a comparison between countries since our main objective was oriented towards the creation of common and comprehensive solutions. Each country or region has the same basic problem (youth unemployment), but with different causes and effects that are difficult to compare.

5. Discussion

Our research led us to identify the main concern about skill improvement: to cope with change and uncertainty in the employment market and to obtain skills to be employable. Therefore, our data indicate a focus on variability and diversity, and the competency to be developed is that of flexibility, inclusivity, diversity, and wellbeing (ability to handle stressful situations and obstacles, promoting wellbeing; the ability to adapt to uncertainty and changes; and the ability to learn and organize their learning).

Innovative and creative skills were also identified in order to manage information, identify and solve problems, and take decisions. Therefore, our data indicate a focus on new technologies (information and communication technologies), and the competency to be developed is that of innovation and knowledge management (ability to work with information, to identify problems, to make independent decisions, and digital skills associated with ICT).

As a major concern with strategic and organisational skills, effective communication also appears not only as an interpersonal skill but also as the ability to lead others and work within a team. Therefore, our data indicate a focus on organisational performance, and the competency to be developed is the mobilization of human resources (ability to organize and manage; to lead a team; to work in a team; to communicate with people; to negotiate).

An international dimension in skills development was also emphasised, in order to work in intercultural/international environments. Therefore, our data indicate a focus on globalisation, and the competency to be developed is international orientation (knowledge of foreign languages and intercultural skills).

A focus on changing economic conditions also appeared, and the competency to be developed is entrepreneurship, defined as the ability to identify goals and act accordingly, to identify risks and opportunities, and to turn an idea into a successful product.

A major concern with communication led us to identify a focus on the necessity of communication, and the competency to be developed is presentation (ability to communicate arguments and attitudes in writing and verbally; ability to persuade; presentation skills).

Our results are in congruence with national reports and with the best practice research in each partner country, and they reveal the necessity to develop competencies adapted to the current social context and in circumstances following a pandemic, in the form of flexibility, inclusivity, diversity, and wellbeing; innovation and knowledge management; entrepreneurship; presentation; the mobilisation of human resources; and international orientation.

A recent study, related to the pandemic context, also emphasised that training should be more in line with young people’s increased awareness of environmental and organisational changes and the development of an international orientation [

25].

A major contribution of our programme was derived from our approach to the issue of unemployment, directed at reducing the gap between the training received and the needs of employers. Therefore, our project included not only the training operators but also employer opinions and practices, as a key to the solution.

Recently, some researchers [

26] have also emphasised the necessity of assessing training programmes in terms of their capability to empower workers with skills and relationships with employers.

Therefore, the competencies (e.g., flexibility, communication, international orientation) that our results also emphasised as required for filling the gap between the training received and the needs of employers are more in congruence with a growing valorisation of leadership characteristics than technical management competencies, to create value for employees and organisations [

3].

6. Practical Implications

A major practical implication of our research was the development of a course programme structured in six categories, a specific training programme that emphasises the know-how and skills that employers will value, which has been made available online as an e-learning course and whose effectiveness will be monitored in future studies.

7. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

One of the limitations of our study is the size of our sample, both in the focus group and in the questionnaires. As a suggestion for future studies, it would be important to complete an intervention programme, a longitudinal study, with unemployed youth and find out whether the training developed by the structured training programme in the six skills had an impact on improving those same skills and strategies not only to find a job but also to retain it.

8. Conclusions

From the analysis of national reports, youth unemployment is a transversal reality. Therefore, it seems important to continue the national and European efforts to create opportunities for young people.

This project is one of these opportunities. It is an initiative developed to fill the gap between the training received by young people and the needs of employers, with the objective of presenting a specific training programme, with know-how and skills that employers will value.

According to this objective, the training needs most highlighted in all the partner countries for sustainable employment were organised into the development of six competencies: flexibility, inclusivity, diversity, and wellbeing; innovation and knowledge management; mobilisation of human resources; international orientation; entrepreneurship; and presentation.

According to the literature, we can conclude that the main skills employers in Europe are looking for refer more to leadership characteristics than management technical competencies.