1. Introduction

The positive effect of transformational leadership on the work processes of employees and its outcomes has been extensively documented in both Western and Eastern literature [

1]. Transformational leaders possess characteristics that motivate and inspire employees, granting them the autonomy and ability to perform at their best in achieving organizational objectives and goals [

2]. Recent studies in the job resources literature have also shown how transformational leadership, by providing various resources such as performance feedback and personal development opportunities [

3], enhances employees’ job performance.

Consistent with the view that management (i.e., leadership) is responsible for shaping job characteristics [

4], a few issues remain unanswered and under-explored. Existing research has demonstrated how organizational factors like culture, climate, and leadership impact employee behavior [

5]. However, most studies have examined these organizational factors in isolation, failing to consider how they function within a specific organizational culture. This is significant because organizational culture defines the expected behavior and norms for both leaders and employees, and the hierarchical culture commonly found in Eastern countries may differ in values and beliefs from the conceptualization of transformational leadership derived from the West. These differences in values and beliefs could weaken the situational strength and effectiveness of transformational leadership within the organization. Moreover, the current literature on job resources often treats all resources as equal and fails to acknowledge their unique roles and functions, as well as their connection to different leadership styles. We argue that each job resources plays different roles and functions, and even more, as unique behaviors of the different leadership styles. Thus, it is important to distinguish and specify the specific job resources in relation to the leadership style to acquire a more holistic understanding of the dynamics between leadership and job resources.

In the current study set within an Eastern country, using the situational strength perspective [

6], we investigate the moderating effect of hierarchical culture on the relationship between transformational leadership within the motivational pathway context (i.e., job resource → higher job performance). We follow the argument that the messages that hierarchical culture carries may undermine the effectiveness of transformational leadership within an organization due to the inability of transformational leaders to construe the organization similarly to that of the culture. As such, a low situational strength between hierarchical culture and transformational leadership may lower or even turn positive influences into negative ones. Organizational culture is important, as it conveys its beliefs, values, tradition, and expected work behaviors as part of the organization’s identity [

7]. Hierarchical culture emphasizes inflexibility, high control, and little empowerment for its employees in ensuring stability and clear adherence to rules and procedures [

8]. This culture is often practiced in conservative, Asian regions whereby due to substantial control from management, it is often observed that employees would exhibit reactiveness rather than proactivity in the workplace [

9].

The present study makes three important contributions to the existing literature. Firstly, it highlights the importance of considering the interaction between two organizational contexts, namely organizational leadership and organizational culture, which has been largely overlooked in the job resources literature. While prior research on transformational leadership has established its beneficial outcomes for employees, such as personal development and autonomy [

10] in both Western and Asian countries [

1], they have not considered the conditions whereby transformational leadership operates under organizational culture. Understanding the role of organizational culture is crucial for a comprehensive analysis of the organization. Therefore, this study contributes by examining the role hierarchical culture may play when transformational leadership is present, while considering both hierarchical culture and transformational leadership as organizational contexts [

11].

Although prior studies have examined supervisory support, autonomy, and social support as distinct forms of job resources [

12], the second aim of this study is to understand the mechanism though which transformational leadership may enhance employees’ job performance specifically by considering the specific job resource of performance feedback, as performance feedback is acknowledged as a crucial factor to achieve higher job performance [

13]. More importantly, it is aligned with transformational leadership behavior which emphasizes communication and the objective to achieve organizational objectives and goals as a team [

14]. Hence, performance feedback takes the focus as the job resources in this particular context.

Thirdly, characterized by high power distance [

15] and presumed hierarchical culture, there is a lack of objective measurements for this situation in Malaysia. Thus, the current study adopts a multilevel perspective involving 44 organizations, to observe how each organization functions within their own context of hierarchical culture and transformational leadership. By using Malaysian samples, this study provides a relevant and suitable sample for investigating the effects of both hierarchical culture and transformational leadership on employees. This research adds value to the literature related to Eastern countries, which significantly differs from the Western world in terms of work dynamics [

16]. The proposed model is illustrated in

Figure 1.

This paper is divided into five parts. We first present the literature review, discussing the relationships among the variables under study (i.e., transformational leadership, performance feedback, job performance, and hierarchical culture). Then, we present the methods, detailing the study design, participant characteristics, as well as the instruments used. After that, we present the results from the study using hierarchical linear modelling, followed by discussing the findings of the study and providing recommendations to stakeholders. Finally, we wrap up the chapter with a general conclusion.

2. Review of Literature

2.1. Transformational Leadership, Performance Feedback, and Job Performance

Transformational leadership refers to a collaborative relationship between leaders and followers aimed at advancing to higher levels of morale and motivation which encompasses idealized influence, individual consideration, inspirational motivation, and intellectual stimulation [

17]. Extensive research treating transformational leadership as a global construct has revealed its positive influence on various work outcomes, including enhanced self-efficacy among employees [

18], increased creativity [

19], and improved performance [

20]. Transformational leaders inspire their employees through participative discussions and bridge the gap between employees’ abilities and organizational expectations by providing performance feedback and facilitating personal development [

20].

The present study predicts that transformational leadership has a positive relationship with performance feedback to employees, owing to the elements of inspirational motivation and individualized consideration [

20]. Performance feedback is defined as information of an employee’s behaviors with regard to prior standards of performance that were established [

21]. In the Malaysian workplace context, performance feedback is often seen in the form of feedback provided to employees by their supervisors or managers with the motive of improving job performance. Job resources encompass the physical, psychological, organizational, or social features of a job that could be useful for the attainment of goals, lessening the physiological or psychological demands and costs of a job, or being capable of inspiring self-development, knowledge attainment, and individual growth [

22]. Given the variability of job resources, this study solely focuses on performance feedback as an indicator of job resources [

23].

Transformational leadership places a strong emphasis on personal employee consideration, recognizing that each employee possesses unique personality traits, skills, knowledge, and talents [

24]. When employees perceive that their well-being is valued and their personal needs and goals are acknowledged by their leader, they respond more positively to their work and job responsibilities. By recognizing that every employee is unique and different, transformational leadership provides an avenue for employees to develop themselves according to their current needs, ultimately contributing to the achievement of organizational goals and objectives [

24]. In such an environment, employees are provided with opportunities to identify areas of improvement relevant to their job, thereby motivating them to enhance their performance. Performance feedback from leaders increases employees’ motivation to improve [

25].

Additionally, the provision of performance feedback can contribute to increased enthusiasm and enjoyment among employees at work, leading to increased job performance and work quality [

26]. Recognizing each employee’s unique qualities and capabilities, a transformational leader tailors their approach and provides relevant information to facilitate self-improvement among employees [

24]. Without feedback, it is difficult to gauge one’s performance level and make necessary improvements [

27]. According to self-determination theory [

28], employees are energized when they receive comments that addresses their autonomy and competency needs. Autonomy needs are fulfilled by granting employees space to exercise their abilities within the task context, while competency needs are fulfilled when employees can utilize personal expertise to demonstrate personal contribution in their roles. This, in turn, fosters a sense of worthiness and belonging within the organization.

Furthermore, it is important to note that performance feedback can also come from fellow employees, instead of solely from the leader. For instance, in virtual teams that are separated by geographical distance, employees from the same project cannot meet each other physically, but the presence of transformational encourages more positivity and more participation in terms of feedback among team members [

29]. This is attributed to a high level of team-perceived self-efficacy and strong team cohesion from a transformational leader. A recent meta-analysis [

30] has also shown a strong correlation between feedback-seeking behavior and transformational leadership.

H1. There is a positive relationship between transformational leadership and performance feedback.

H2. There is a positive relationship between transformational leadership and job performance.

2.2. Performance Feedback and Job Performance

There are two components that characterize performance feedback—one that is evaluative in nature, and the other that is informative in nature. While the evaluative aspect offers more specific guidance on how individuals can modify their performance strategies, the informative aspect offers employees with information about their performance and how they implement work strategies [

31]. This is crucial as it enables employees to understand the expectations regarding their work behaviors and outcomes [

27]. As previously mentioned, performance feedback has been associated with numerous positive outcomes, including higher job satisfaction, increased organizational commitment, and ultimately, improved job performance [

32].

Performance feedback plays a vital role in fostering self-awareness among employees regarding the state one is currently in and the desired place that they should be striving to be at [

33]. It empowers individuals by changing one’s usual actions and practices to achieve greater goals. In fact, performance feedback has been recognized for being an essential component for attaining greater levels of performance on a job [

13]. By receiving performance feedback, employees develop intrinsic motivation as they develop a sense of identification with their work. Intrinsic motivation, arising internally within individuals and not driven by external factors, has a greater impact on employee cognition, affect, and behavior compared to extrinsic motivation [

28,

34]. Derived based on characteristics of a job that are useful for employees [

35], performance feedback enhances motivation and empowers employees to take ownership of their work. This heightened motivation ultimately leads to improved performance in the workplace.

H3. There is a positive relationship between performance feedback and job performance.

2.3. Performance Feedback as a Mediator

Employees that receive a more feedback on their performance tend to experience a greater sense of empowerment, which motivates them to excel in their work [

13]. In the context of transformational leadership, individualized consideration plays a significant role in empowering employees and providing them with opportunities to take ownership of their job responsibilities [

36]. Consequently, these empowered employees often exhibit increased passion towards their work [

37]. More importantly, performance feedback enables employees to align their efforts with organizational goals, focusing on the collective objectives rather than solely on individual engagement [

38]. Overall, these dynamics illustrate how the practices of transformational leadership (i.e., performance feedback) can serve as a supportive factor in enhancing employees’ job performance by providing relevant and constructive feedback that is related directly to the job performance.

H4. The relationship between transformational leadership and job performance is mediated by performance feedback.

2.4. Hierarchical Culture as a Moderator

The definition of organizational culture is common “values, assumptions, and beliefs” shared by members from the same team [

39]. While leadership can directly influence employees’ work behaviors, hierarchical leadership may serve as an indirect influencer on employees’ work behaviors [

11]. Research has shown how organizational culture, such as market and clan culture, can impact employees’ job performance [

40]. As for hierarchical culture, studies have shown that it affects employee empowerment and organizational effectiveness [

41].

Building upon the situational strength perspective, which examines the interaction between transformational leadership and hierarchical culture, we propose that transformational leadership within a hierarchical culture may lead to greater discrepancies in transmitting values, beliefs, and expected behaviors among employees. This can subsequently impact the effectiveness of transformational leadership in delivering performance feedback and, ultimately, employees’ job performance.

Hierarchical organizational culture is characterized by formalized and structured procedures governing employees’ actions [

42]. It emphasizes the importance of ensuring consistency, predictability, and effectiveness by operating through a structured chain of command [

43]. In such cultures, management often places a high value on status and position, where using power and authority, control is exerted [

44]. Owing to this, most important decisions are made by people that are at the managerial level. Employees are typically discouraged from voicing their opinions or offering perspectives that differ from those of management [

45]. The emphasis on order and stability aims to ensure smooth operations and overall organizational effectiveness.

While organizational culture shapes employees’ intended behaviors, leaders’ expected behaviors are also influenced, as leaders are responsible for embodying and enacting the desired cultural norms [

46]. Transformational leaders who frequently provide performance feedback as a means of empowering their employees may encounter challenges within a hierarchical culture. We propose that hierarchical culture and transformational leadership present different approaches to employee management. Leaders, being closer to the employees than the distant organizational culture, seek to maintain alignment with how the culture governs the organization [

47]. Organizational culture often influences the leadership style [

48], and leaders who fail to synchronize their style with the culture may be perceived as ineffective.

Thus, considering that transformational leadership emphasizes performance feedback and provides a supportive context, while hierarchical culture may not, we posit that the presence of hierarchical culture within transformational leadership will impact the positive effects of transformational leadership on employees. This may be due to employees receiving conflicting information, leading to confusion regarding the correct course of action to follow.

H5. The relationship between transformational leadership and performance feedback is moderated by hierarchical culture.

However, in some ways, within a hierarchical culture, employees may face challenges in achieving high levels of job performance. For example, hierarchical culture establishes a social hierarchy based on positions and authority, creating a sense of distance between management and employees [

43]. This culture tends to overlook employees’ thoughts, ambitions, plans, and ideas. Additionally, it creates barriers that hinder employees from showcasing their competencies, exercising autonomy, and fostering relationships. These factors collectively impede employees’ ability to receive performance feedback at work. As providing feedback for one’s performance is treated as a valuable resource on the job, when lacking, it indicates poor availability of job resources [

12]. With limited job resources, employees experience reduced intrinsic motivation in carrying out their daily tasks [

48]. Consequently, there is a distance that is perceived by the employees with regards to themselves and their jobs, as they are unable to fully engage and excel in their work due to management control and segregation.

In summary, in an environment where hierarchical practices prevail, employees experience a weakened sense of connection to their work, leading to a lack in performance feedback. Consequently, this leads to lower levels of job performance.

H6. The relationship between transformational leadership and job performance is moderated by hierarchical culture.

3. Methods

3.1. Participants

This research utilized a multilevel cross-sectional design, involving 44 teams totaling to 256 white-collar employees that were recruited from private organizations in the main cities of Malaysia. White-collar employees were specifically selected to capture a more accurate depiction of the relationships between employees, leaders, and the organization within a typical workplace setting. Participants consisted generally of Malaysians (N= 248, 96.9%), with a gender distribution of a slight female majority (N = 138, 53.9%). The mean age of the participants was 35.2 years (SD: 12.3), and their average tenure in the organization was 5.48 years. The distribution of participants based on industries was varied where a large majority were service industries (65.2%), some from the consumer product industry (18%), while the remaining participants from a mixture of various industries. The distribution of industries mirrors the demographic of industry in Kuala Lumpur [

49] which is the capital city of Malaysia. There were a range of four to nine participants in each team.

This research was conducted in 2015 by the main researcher. Prior to data collection, the study has obtained ethics approval from the main author’s university ethics’ committee board (Approval Number: UMREC/2012/039). Initially, a list of organizations was obtained from a database containing top organizations in terms of market capitalization in the country. These organizations were then contacted via email to gauge their interest in participating in the study, which had received ethics approval from the ethics board. Upon expressing interest, the researchers met with the organizations to provide further explanation about the study and the data collection process. Only one department was selected to join the study to allow a better overview of the multilevel aspects of hierarchical culture and transformational leadership of various organizations. Participants were given a set of questionnaires to complete and were instructed to return them in a sealed envelope in the designated drop box. No personal identification was collected. The data were then coded using a letter to represent each organization and a number to identify each participant within that organization.

3.2. Instruments

English questionnaires were used to retain their original meaning and purpose of the scales. Therefore, in order to ensure that participants possess sufficient English proficiency, we requested the department head to exclusively choose employees who had a satisfactory level of English comprehension.

Hierarchical organizational culture is evaluated with six items of the Organizational Culture Assessment Instrument (OCAI) [

50]. The scale uses a score of 100 to measure four distinct organizational culture (hierarchical, clan, adhocracy, and market) whereby greater ratings for the hierarchical scale indicate greater hierarchical culture in an organization. A sample of an item in this instrument is “The organizational is a very controlled and structured place. Formal procedures generally govern what people do”.

Transformational leadership is evaluated using 23 items from Transformational Leadership Inventory [

51] whereby there are six aspects of transformational leadership that are included, namely intellectual stimulation, individualized support, articulating a vision, high performance expectations, providing an appropriate model, and nurturing acceptance of group goals, but has been tested as being one-dimensional [

50]. Items in the scale are rated on a Likert scale of 1 to 7 (strongly disagree to strongly agree). A sample item in this scale is “My leader has a clear understanding of where we are going”.

Performance feedback is measured with three adapted items [

52]. Items in this scale are rated on a Likert scale of 1 to 5 (never to always). A sample of an item asked in this scale is “Does your work provide you with direct feedback on how well you are doing your work?”

Job performance consists of a six item scale [

53] that was rated on a Likert scale of 1 to 5 (strongly disagree to strongly agree). A sample of an item asked in this scale is “I strive to meet deadlines”.

3.3. Analysis Strategy

In assessing the appropriateness of transformational leadership and hierarchical organizational culture as constructs operating at multilevel, we conducted the inter-rater agreement analysis [

54]. The analysis returned an r(WG)(J) value of 0.95 and 0.94, respectively, for transformational leadership and hierarchical organizational culture that was higher than the 0.70 suggested, reflecting their suitability to be used as multilevel constructs [

55]. Next, the intraclass coefficient (I) (ICC[I]) for transformational leadership and hierarchical organizational culture were examined. The resulting values of 0.12 and 0.17, respectively, were within the suggested values of 0.05 to 0.20 [

56]. The analysis indicates that 12% of the variance in transformational leadership and 17% of the variance in hierarchical organizational culture were attributed to organizational factors. A one-way random effect analysis of variance (ANOVA) for transformational leadership and hierarchical organizational culture was also conducted. The resulting F(

III) values for transformational leadership of 2.12 and the hierarchical organizational culture of 2.31 where

p < 0.001 further indicated that the variance in transformational leadership and hierarchical organizational culture was due to organizational levels. We also found no gender differences on the investigated variables. Hence, gender was not controlled.

To examine the hypotheses in this study, the lower-level outcomes variables level were regressed on lower-level independent variables. Next, the cross-level effects (L2 predicting L1) were evaluated [

57].

The individual-level equation is illustrated as follows:

The following is an example of a cross-level effect equation:

The lower-level variable’s dependent variable was regressed against the independent variable for lower-level direct effect (H3). To illustrate, job performance is regressed against performance feedback in H3 (refer to Model 1).

For the moderating effects (H5 and H6), taking H5 as an example, the lower variable dependents (performance feedback) are regressed against the independent variable (transformational leadership) at the lower level. Then, transformational leadership was added on level 2 on the first line, followed by the moderator (hierarchical culture) on the second line of level 2 (see Model 6).

An example of a moderation analysis HLM equation is as follows:

Finally, to test the mediation effects (Hypotheses 4), a split design was used to test each part of the mediation pathway ab using estimates of path a (X→M) and path b (M→Y) [

58]. As an example, for H6, we ensure that the mediation steps that a proposed by [

59] were fulfilled. For the first step, a significant relationship is found for X→Y (Transformational leadership predicting Job performance) (Model 3). Then, for the second step, a significant relationship was also found for the relationship of X→M (Transformational leadership predicting Performance feedback) (Model 5). For the third step, we also found a significant relationship between M→Y, in the presence of X (Transformational leadership + Performance feedback→Job performance) (Model 2). Given that the relationship from X to Y remains significant when M is included in the third step, this would be considered as a partial mediation. Where the inclusion of M produces a not significant relationship from X to Y, a full mediation has occurred. Monte Carlo test [

60] is used to confirm the mediation relationship. The mediational effects are tested using estimates from Path a (X→M) and Path b (M→Y) where a mediation is significant if the values of the lower level (LL) and upper level (UL) lie within a range that does not include the value of zero (0) [

61]. We conducted the Monte Carlo test using a 95% confidence interval (CI) and on 20,000 repetitions.

4. Results

Table 1 shows descriptive analysis and correlations between all variables at levels 1 and 2. Results for HLM analyses are shown in

Table 2. The summary of the findings is illustrated in

Figure 4.

For Hypothesis 1, it was proposed that there is a positive relationship between transformational leadership and performance feedback. It was found that transformational leadership is positively related to performance feedback (γ = 0.46, p < 0.05). Therefore, Hypothesis 1 was supported. See Model 5.

For Hypothesis 2, it was proposed that there is a positive relationship between transformational leadership and job performance. The analysis demonstrated transformational leadership to be positively related to job performance (γ = 0.37, p < 0.05). Therefore, Hypothesis 2 was supported. See Model 3.

For Hypothesis 3, it was proposed that performance feedback is related positively to job performance. It was found that performance feedback was positively to job performance (β = 0.22, p < 0.05). Hence, Hypothesis 3 was supported. See Model 1.

For Hypothesis 4 it was proposed that the relationship between transformational leadership and job performance is mediated by performance feedback.

Using Model 5 as a parameter estimate for the value of the direct effect from transformational leadership to performance feedback (γ = 0.46, SE = 0.07) and Model 2 as the estimated parameter value for the relationship of performance feedback→job performance with transformational leadership in the model (β = 0.23, SE = 0.07), the mediation hypothesis was evaluated. The results found performance feedback to be a significant mediator (95% CI, LL = 0.03897, UL = 0.1822) of the relationship between transformational leadership and performance feedback. Therefore, Hypothesis 4 was supported.

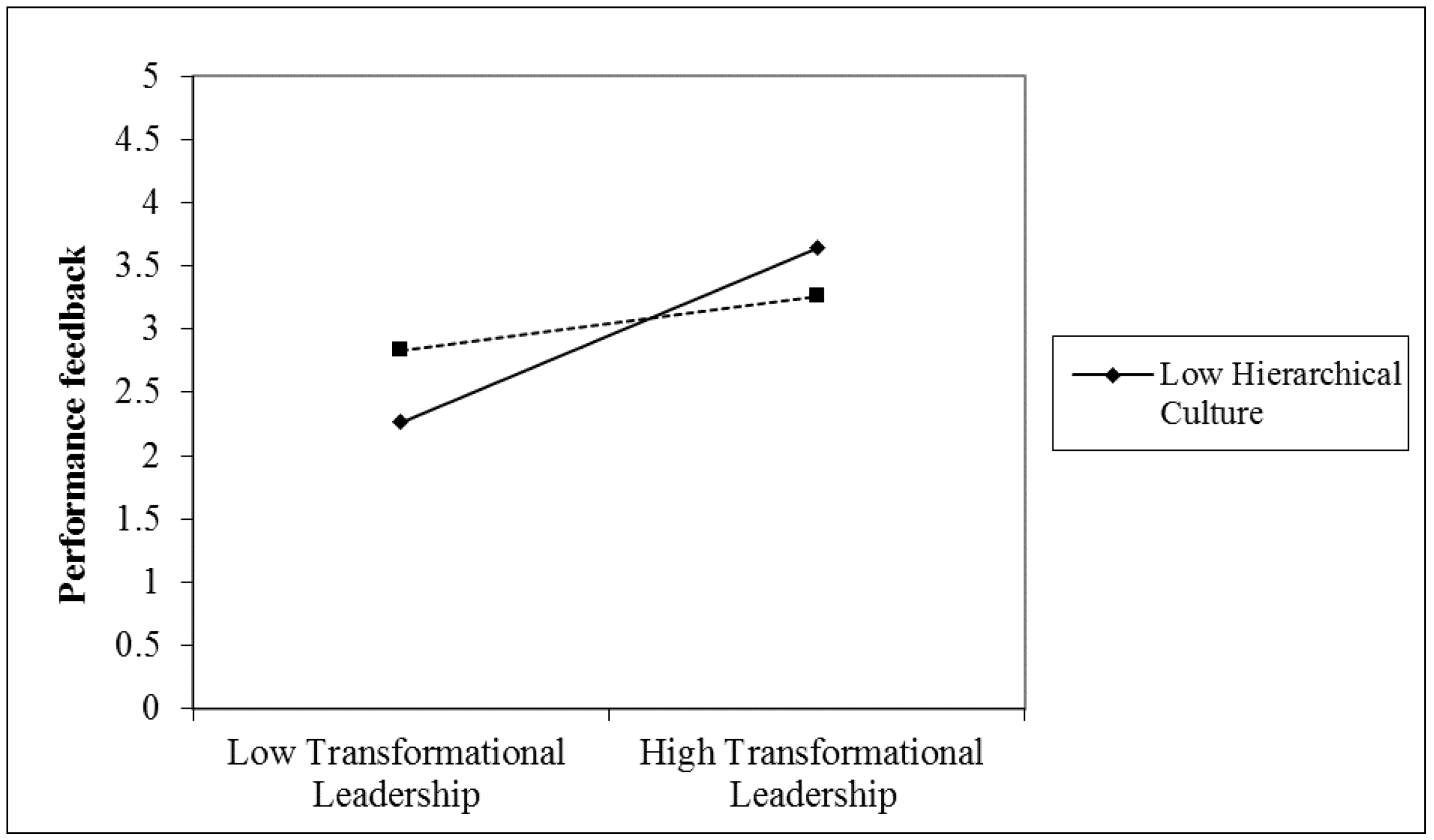

For Hypothesis 5, it was proposed that hierarchical culture is a moderator of relationship between transformational leadership and performance feedback. Refer to

Figure 2, in the presence of hierarchical culture, a significant negative relationship between transformational leadership and performance feedback was found (γ = −0.12, significant at one-tailed). Therefore, Hypothesis 5 was supported. See Model 6.

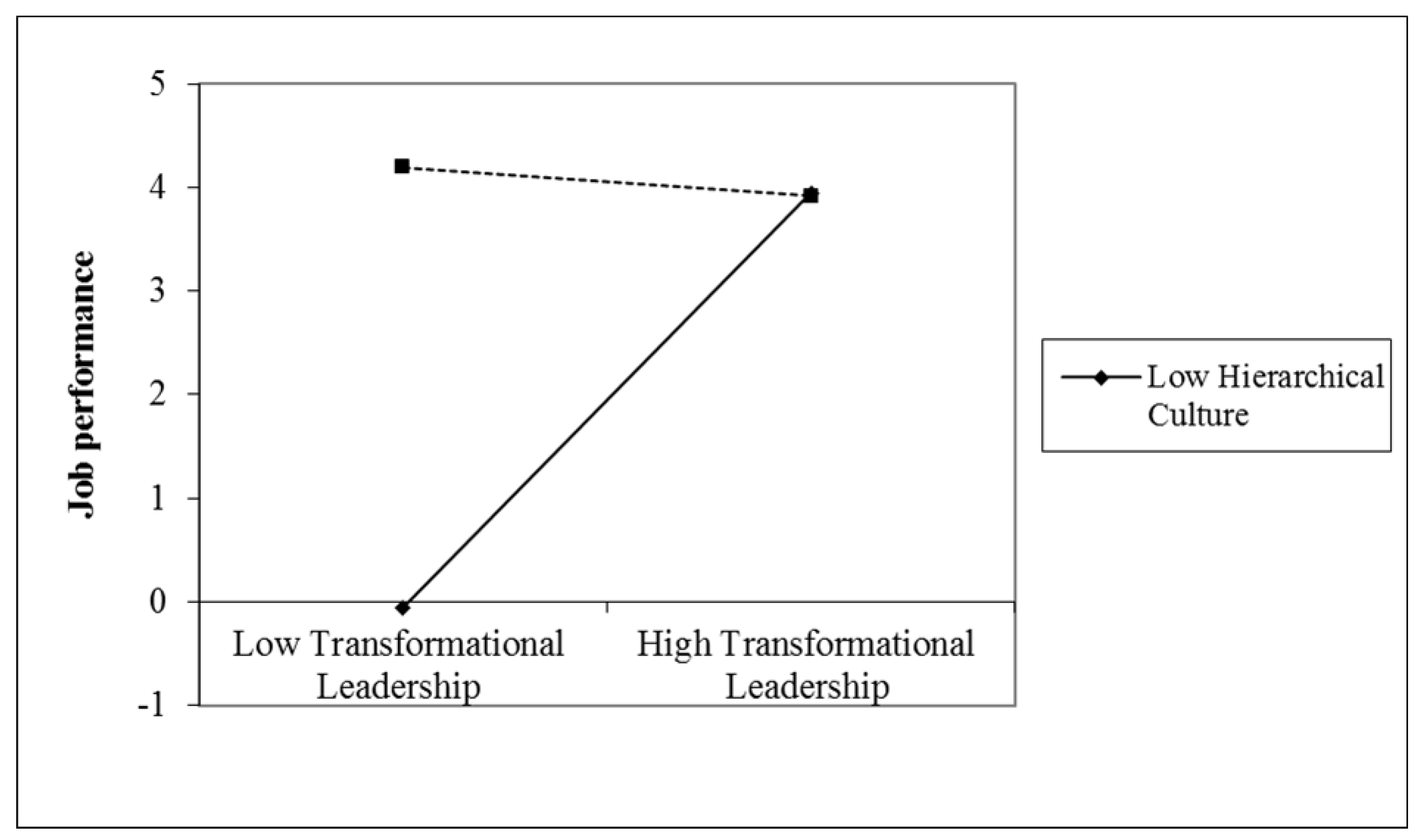

For Hypothesis 6, it was proposed that hierarchical culture is a moderator of the relationship between transformational leadership and job performance. Refer to

Figure 3, the analysis found that in the presence of hierarchical culture, there is a significant negative relationship between transformational leadership and job performance (γ = −0.15,

p < 0.05). Therefore, Hypothesis 6 was supported. See Model 4.

Figure 3.

The interaction effect of transformational leadership and hierarchical culture on job performance. The dotted line represents high hierarchical culture.

Figure 3.

The interaction effect of transformational leadership and hierarchical culture on job performance. The dotted line represents high hierarchical culture.

5. Discussion

The primary aim of this research is to assess the impact of transformational leadership on the performance feedback and job performance of employees. Additionally, the role of hierarchical culture as a moderating variable between them is examined. Our findings revealed that transformational leadership positively influenced performance feedback and job performance; however, when there is a high level of hierarchical culture, these relationships become negative.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

In essence, our study revealed that the presence of transformational leadership alone positively influenced employee job performance, aligning with previous research highlighting the positive outcomes associated with transformational leadership in both Western and Eastern countries [

62,

63]. Transformational leadership stimulates employee motivation by acknowledging the unique capabilities and skills of each individual. [

24]. Similarly, performance feedback can also increase employee motivation [

3] by helping employees assess their present and desired states, stimulating internal motivation to perform better at work [

64]. This supports the self-determination theory, indicating that transformational leaders can offer valuable job resources (i.e., performance feedback) for employees to perform well at work. By addressing employees’ competence needs and enabling their contribution to organizational goals through performing well at work with feedback, transformational leadership enhances overall job performance.

The study further investigated the situational strength between transformational leadership and hierarchical culture and supports the proposed situational strength perspective [

6]. Interestingly, we found that the simultaneous presence of both factors resulted in lower levels of performance feedback and job performance. While transformational leadership demonstrated positive associations with performance feedback and job performance, hierarchical culture was a moderator for these relationships, leading to reduced levels of performance feedback and job performance.

With a further look into the interactions of transformational leadership and hierarchical culture on performance feedback and job performance, a high transformational leadership showed the highest level of performance feedback under low hierarchical culture. A low transformational leadership under low hierarchical culture showed the lowest level of performance feedback. Regarding job performance, high hierarchical culture in combination with low transformational leadership was associated with the highest level of job performance, while low hierarchical culture with low transformational leadership corresponded to the lowest level of job performance. These findings indicate that transformational leadership is strongly linked to performance feedback, while hierarchical culture is more closely associated with job performance. Moreover, the results suggest that each organizational context (i.e., transformational leadership and hierarchical culture) is most effective when the other context is low in its presence.

Our findings suggest that the values and beliefs underlying transformational leadership and hierarchical culture may differ but can also complement each other in certain aspects. Hierarchical culture, emphasizing stability and control within the organization, restricts employee freedom and autonomy [

49]. Previous research on hierarchical organizational culture found a negative relationship with job performance and job resource [

65,

66]. In a Malaysian context, characterized by perceived high collectivism and power distance, trust levels among individuals are relatively low [

67]. Nevertheless, despite the low trust, employees exhibit loyalty to higher authorities [

68]. However, the culture of withholding information and exerting power and position prevents the provision of adequate performance feedback. As a result, this limits employee development and subsequently reduces job performance [

69].

The findings also indicate that although transformational leadership and hierarchical culture work best when the other organizational context is low in its presence, the other organizational context still plays a role when the organizational context is low in its presence. Thus, it is crucial to examine the interaction effect of organizational culture with leadership styles. Our study highlights how aligning and creating coherence between organizational culture and leadership style are essential to preventing employee confusion regarding the organizations’ functioning. Conflicting organizational aspects disrupt effective and productive operations [

70].

It is important to exercise caution when both organizational contexts are low in their presence. Considering these findings collectively, it becomes evident that both factors significantly impact employees’ outcomes. Specifically, transformational leadership serves as a positive antecedent, while hierarchical culture transforms this relationship into a negative one. These observations align with social exchange theory [

71], which explains how employees respond to their work environment. When employees experience a positive and caring work environment, they reciprocate by performing better, ultimately benefiting the organization.

5.2. Practical Implications

In Eastern countries known for practicing a collectivistic and hierarchical organizational culture [

72], the present study provides support for the applicability of situational strength between transformational leadership and hierarchical organizational culture. The study found negative interaction effects on leaders’ performance feedback behavior and employees’ job performance. Organizations in Eastern countries should prioritize addressing the low situational strength of transformational leadership within a hierarchical organizational culture. Individuals tend to value job resources like performance feedback as they aid in completing their work effectively [

3].

Organizational culture represents the identity of an organization: it conveys the values and principles of organizations, dictates, and influences employees’ behavior [

7]. Thus, while transformational leadership is positively related to employees’ work outcomes, it is more important to consider the leader–culture fit in ensuring compatibility between the leadership style and the organizational culture [

73]. Organizations need to reassess the leadership styles that align with a hierarchical organizational culture, seeking to harmonize leadership practices with organizational values. One such suitable leadership style is paternalistic leadership, which also aligns with hierarchical culture [

74]. Paternalistic leadership comprises benevolence, morality, and authoritarianism [

75]. Studies have started to recognize the benefits of paternalistic leadership in Eastern countries, where similarities with hierarchical organizational culture exist (e.g., [

76,

77]).

The presence of leaders who do not align with the values of organizational culture may lead to negative consequence as this can lead to misalignment with organizational objectives instead of fostering synergy within the organization [

78]. Therefore, despite the positive impacts on employees that are associated with transformational leadership, we recommend that organizations embrace a style of leadership which aligns with a hierarchical organizational culture that is suitable for implementation within societies that are collectivistic in Asian countries like Malaysia. Re-evaluating how organizational leadership and culture can enhance their situational strength, organizations may consider revising or adopting a similar organizational culture that fosters synergies for the positive effects of transformational leadership. This could involve emphasizing a clan organizational culture, which prioritizes relationships over control while still preserving cultural elements of obedience. The focus on human relationships allows employees a sense of belonging, aligning with the characteristics of transformational leadership that emphasizes personal consideration. This approach can enhance situational strength and facilitate the presence of transformational leadership within organizations. Additionally, it recognizes that there are specific circumstances where transformational leadership is crucial, particularly in industries like manufacturing in Eastern countries [

49].

6. Conclusions

In line with the adoption of a multilevel approach to study social contexts like organizational leadership, climate, and culture that influence individuals [

79] as the more comprehensive approach to investigating organizational issues on employees [

80], this study particularly resonates with the suitability of a multilevel approach in the Asian context due to the prominent top–bottom influence exerted by higher-level management on lower-level employees [

81].

More importantly, this study advances the understanding of transformational leadership not only in a vacuum setting but rather in a specific hierarchical culture that is relevant and applicable within the Asian context. While multilevel studies have made advancements in the study of leadership over the years, none have examined transformational leadership within a specific organizational culture, and this study addresses that gap. Thus, it allows us to observe how organizational contexts may clash and even create negative synergies that impact employees’ job resources and job performance.

However, the study has limitations in deciphering the intricate relationship between the leader, performance feedback, and job performance. Specifically, employing a longitudinal method would enable the exploration of the reverse effects of these variables and investigate whether job performance influences the extent and quality of performance feedback. It is possible that leaders are more attentive and perceptive to high-performing employees, providing them with more valuable feedback, while low-performing employees receive feedback that reflects their inadequate performance. In the transformational leadership and performance feedback relationship, it may be possible that through the performance feedback behavior, the leader’s transformational leadership is enhanced through performance feedback behavior, further strengthening the relationship between the two.

Moreover, while the study focuses on the relationship between lower-level management and employees’ job performance, it falls short of capturing the overall leadership picture within an organizational setting. As the literature states, leadership consists of multiple layers of management: lower-level, middle-level, and top level. This raises several unanswered questions: Will the proposed model hold true for top-level and middle-level management, or will there be differences? There are reasons to believe that top-level management will display values and beliefs that are similar to that of the organizational culture (i.e., hierarchical culture) as they determine how organizations should operate and shape a significant portion of the organizational identity (i.e., its organizational culture). In the case of middle-level management, which is rarely investigated in the leadership literature, it becomes another issue to investigate as middle-level management is the communicator between the top-level management and the lower-level management and ensuring information, procedures, and expectations are conveyed correctly. Exploring these questions contributes to the features of employees who are middle-level management and lower-level management, who may align themselves with the organizational culture, thus presenting a different dynamic to the proposed model.

Thus, future studies should investigate the interplay between organizational culture and organizational leadership, encompassing top-level and middle-level management. In the event that the hierarchical aspect of organizational culture is less pronounced, and instead, clan, market, or adhocracy culture is dominant, future studies examining not only transformational leadership but other leadership styles would contribute to the situational strength perspective within the organizational culture-organizational leadership literature. Additionally, employing a longitudinal method coupled with a multilevel approach and considering environmental factors [

58] would enhance methodological rigor. Longitudinal approaches can address the limitations of cross-sectional studies, with the gap between measurements ranging from three months [

4] to two years [

82], as recommended by [

83].

The present study provides support for the relationships of transformational leadership style on performance feedback and job performance in the positive direction, indicating the importance of performance feedback as one of transformational leadership behaviors and the importance of performance feedback in increasing employees’ job performance. However, when transformational leadership is examined within a hierarchical organizational culture, it reveals a negative relationship with performance feedback and job performance. Therefore, organizations should contemplate aligning their organizational culture with the selected leadership style, recognizing that both factors do not operate independently. Future research could, therefore, explore how to further evaluate the different types of organizational culture across various levels of organizational leadership using a longitudinal approach.