Abstract

The research for this study examined the extent to which organisational factors, represented by perceived organisational support and workplace incivility, and individual factors, represented by core self-evaluation (CSE), predicted intrapreneurship. The key hypothesis was that CSE would be associated with intrapreneurship and that incivility and perceived organisational support would serially mediate this relationship. Participants were 410 working adults who volunteered to complete a series of questionnaires measuring CSE, incivility, perceived organisational support, and intrapreneurship. Analysis showed a serial mediation effect between CSE and intrapreneurship through incivility and perceived organisational support. By integrating both individual and organisational antecedents of intrapreneurship from the perspective of CSE, the research illustrates the significant role CSE plays in determining to what extent intrapreneurial behaviours will be exhibited. Findings from this study provide insights for both organisations and researchers in determining the fundamental relationships between individual and organisational factors in predicting intrapreneurial behaviours.

1. Introduction

Encouraging employees to think and work more like entrepreneurs, known as intrapreneurship, has become increasingly prevalent in knowledge-based industries. Intrapreneurship has been linked to increased innovative business performance [1,2] and employee engagement [2,3] as well as to corporate performance [4]. There has been extensive research undertaken concerning the key success factors of intrapreneurship [5,6,7], and to a lesser extent, the barriers to intrapreneurship [8,9]. Research to date has focused primarily on organisational factors, as these are largely within the control of the organization. However, there has been growing research demonstrating the importance of personality, particularly traits of risk-taking and self-efficacy on intrapreneurship [10]. Unfortunately, interest in organisational factors and personality factors has largely occurred in parallel [7,11] with few studies investigating the combined effects of these factors on intrapreneurship [12,13]. The uptake of workplace initiatives aimed at promoting intrapreneurial thinking and behaviour provides strong motivation to consider both individual and organisational factors affecting intrapreneurship in tandem to establish an evidence base that is currently incomplete.

Using the lens of the approach/avoidance theoretical framework [14], this study aims to understand to what extent organisational factors, represented by the facilitative effect of organisational support and the inhibitory effect of incivility, and individual factors, represented by core self-evaluation (CSE), influence intrapreneurship. Specifically, the research investigates the prospect of serial mediation, testing whether incivility and perceived organisational support serially mediate the relationship between CSE and intrapreneurship. By adopting an interactionist approach, examining both the individual and the organisational context, a more thorough understanding of the factors that influence intrapreneurship can be attained.

Numerous learning theories have been utilised to explain our understanding of intrapreneurship [7]. However, with the inclusion of CSE as a determinant of intrapreneurship, the approach/avoidance motivation framework, which has roots in personality research, offers a comprehensive explanation of intrapreneurship that has not yet been explored. In addition, research into intrapreneurship, including its antecedents, has more often explored the moderating effect of individual factors, such as personal initiative or CSE [15], rather than considering personality as a lens through which to analyse the relationship between organisational factors and intrapreneurship.

The paper is structured as follows. The first section outlines the theoretical foundations for the research, defining intrapreneurship and introducing the key organisational (i.e., perceived organisational support and incivility) and individual (i.e., CSE) factors thought to predict intrapreneurship. The approach/avoidance theoretical framework will also be introduced to model the hypothesised relationships. The next section details what procedures and materials were utilised to conduct the research, followed by the major findings. The paper concludes with a discussion of the key findings, the theoretical and practical implications for management practices, as well as limitations and future directions for research.

1.1. Intrapreneurship

Based on the results of a recent meta-analysis [11], at least 73 definitions of intrapreneurship exist. Approximately half of the definitions focus on intrapreneurship as an organisational characteristic while the remaining half concentrate on individual behaviours. The authors propose a new definition of intrapreneurship which integrates both organisational and individual aspects—one that the current research will adopt as it positions the intrapreneur within an organisational context:

“Intrapreneurship is the process whereby employees recognise and exploit opportunities by being proactive and by taking risks, in order for the organisation to create new products, processes or services, initiate self-renewal or venture new businesses to enhance the competitiveness and performance of the organization.”[11] (p. 7).

Unlike entrepreneurs who develop an innovative idea within their own business for personal gain and profit [16], intrapreneurs develop their ideas within organisations [10]. Though they may derive personal gain and success from the idea, their innovations ultimately benefit the organisation in which they work.

1.2. Perceived Organisational Support and Incivility

Organisational support is commonly cited in the extant intrapreneurship literature as a key predictor of intrapreneurship [17]. It refers to the degree to which an organisation appreciates employees’ contributions and well-being [18]. Rather than looking at intrapreneurship from the perspective of managers, several scholars [19,20] argue that how employees perceive their environment, in terms of how much or little support is received from the organisation, is likely to impact employee intrapreneurship behaviours. Perceived organisational support (POS) has been linked to how much effort employees exert on the job [21], and management support, a facet of organisational support [1], has been shown to facilitate the generation of new ideas, which is an antecedent of intrapreneurship [22]. Indeed, increased levels of management support have been identified as an enabling factor of intrapreneurship [20,23] and have been found to positively predict innovation and performance [1,24].

Tolerance for risk-taking is another fundamental component in the creation of new products, processes or services, and central to the definition of intrapreneurship. Hisrich [25] found that new ideas are generally developed through trial and error. Consequently, organisational support is required to foster an environment that accepts failure and embraces ambiguity. Teamwork and tolerance for mistakes have also been cited as organisational factors that enhance intrapreneurship, in addition to job satisfaction [25,26]. More recently, perceived organisational support has been found to positively predict employee intrapreneurial intention [20]. Based on this body of research, the current work hypothesises that perceived organisational support will positively predict intrapreneurship (H1).

Building on the literature linking organisational support to intrapreneurship, recent studies have focused on how deficits in an organisation’s environment, such as workplace incivility, can suppress intrapreneurship. Workplace incivility is described as “low-intensity deviant workplace behavior with an ambiguous intent to harm” [27] (p. 457). Incivility is different from other forms of workplace aggression such as bullying in that incivility is lower in intensity and unclear in its intent to damage, in contrast with bullying which is more overt and purposeful. However, consistent with bullying, incivility is associated with a range of negative individual and organisational outcomes. Workplace incivility affects employee engagement, job performance and satisfaction [28], and employee turnover [29]. Individuals who experience incivility in the workplace tend to distrust their organisation [30] and engage in less discretionary citizenship behaviours [31]. Important to intrapreneurship, incivility has been found to negatively affect collaboration and creativity [32], both of which are precursors to intrapreneurship.

Yariv and Galit [13] were amongst the first to ask the question and empirically investigate whether workplace incivility can inhibit intrapreneurship. Drawing on social exchange theory [33], the authors proposed and tested a mediated model where incivility both indirectly (via organisational support) and directly predicted intrapreneurship. They reasoned that if employees perceived a lack of organisational support, as is the case with workplace incivility, employees would be less resourceful in generating new ideas. The result of their work with over 21 organisations showed that organisational support directly predicted intrapreneurship and fully mediated the relationship between incivility and intrapreneurship. Therefore, in line with Yariv and Galit [13], the current work hypothesises that perceived organisational support will fully mediate the relationship between incivility and intrapreneurship (H2).

Interestingly, Yariv and Galit [13] hypothesised, but did not find support for, a negative relationship between incivility and intrapreneurship. One potential explanation for this nonsignificant result is that the researchers did not consider the importance of the individual. Certainly, recent work suggests that individual differences may act as a boundary condition on the processes translating perceived organisational support into actual intrapreneurial behaviour [20].

1.3. Core Self-Evaluations

Intrapreneurs are often described as being high in creativity, innovation, vision, flexibility, persistence, resilience, and risk-taking. More recent studies have also linked the individual difference variables of high self-esteem, self-efficacy, internal locus of control, low neuroticism and intrapreneurial self-efficacy with intrapreneurship [7]. In light of this work, the current research proposes the personality trait, core self-evaluations (CSE), as an important predictor of intrapreneurship, as well as a variable likely to shed some light on how incivility and perceived organisational support impact intrapreneurial behaviours. CSE captures an individual’s assessment of their worth, confidence, capabilities, and level of control over their life and circumstances [34]. This broad personality trait consists of four superordinate traits including: self-esteem; generalised self-efficacy; emotional stability; and locus of control [34]. Individuals high in CSE have a positive self-concept about themselves and their ability to impact their environment and tend to experience higher levels of job satisfaction, engagement, motivation, and work performance [35,36,37,38], while individuals very low in CSE have been found to experience a pay penalty, receiving on average six percent less in income [39].

CSE is thought to be particularly relevant to intrapreneurship, considering the breadth of research demonstrating direct relationships between CSE facets and intrapreneurial behaviour [40] as well as research identifying CSE as a subconstruct of intrapreneurial self-efficacy [20,41]. CSE has also been repeatedly linked to workplace creativity [42], a precursor to intrapreneurship [15]. Further convergent evidence is provided by a recent comprehensive review on entrepreneurship which demonstrated the important influence of self-efficacy on the development of entrepreneurial intentions and mental states as well as on entrepreneurial behaviour, venture creation and entrepreneurial performance outcomes [40]. Taken together, the extant research provides compelling evidence to suggest that CSE is likely to predict intrapreneurship (H3).

1.4. CSE and the Approach/Avoidance Motivation Framework

In addition to influencing outcomes directly, CSE can have an indirect effect on outcomes through appraisals individuals make [37]. The approach/avoidance motivation framework [14], based on Gray’s biopsychosocial theory of personality [43], provides a theoretical framework to explain the effect of CSE on intrapreneurship through incivility and perceived organisational support. It suggests that most experiences can be classified according to whether they facilitate moving toward (approaching) or moving away from (avoiding) stimuli. To date, this framework has predominantly been used to explain and understand both the effects of CSE and workplace aggression [44,45]. The current research contends that the approach/avoidance motivation framework provides a useful tool in explaining how individual and organisational factors interact to predict intrapreneurship.

Conceptualising CSE in line with the approach/ avoidance motivation framework indicates that higher levels of CSE are linked with a strong approach disposition and weak avoidance disposition [45], suggesting that individuals high in CSE are more sensitive to positive stimuli and less sensitive to negative stimuli. In contrast, individuals who score low in CSE are more sensitive to negative stimuli and less sensitive to positive stimuli [44]. It is theorised that acts of workplace aggression, such as workplace incivility where the intent is unclear [46], may produce feelings of anxiety—an avoidance-based emotion—leading to avoidance-based behaviours [47]. Therefore, an individual high in CSE should be less sensitive to workplace incivility than an individual low in CSE. This outcome could then be further influenced by organisational support (or lack thereof), which depending on the perception of the individual, may serve to increase (or decrease) intrapreneurship. Shalley et al. [48] support this view, suggesting that contextual characteristics such as workplace relationships and management support interact with personal characteristics such as personality to predict creativity. This is an important distinction as policies and practices can be developed to improve organisational factors such as incivility and organisational support. Therefore, we hypothesise that CSE influences intrapreneurship, such that individuals high in CSE will exhibit higher intrapreneurship (H3), but that this effect is likely to be mediated by both incivility and perceived organisational support (H4).

1.5. The Current Research

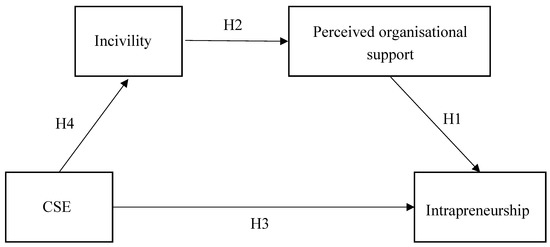

Figure 1 provides a visual representation of the current research and illustrates the serial mediation relationship investigated. The prediction of serial mediation is supported by findings that employees hold management responsible for the levels of incivility within their organisation [49]. Furthermore, organisations that condone workplace incivility fail to provide supportive environments in which employees can feel safe to take risks in the pursuit of creativity [13,48]. As a result, workplace incivility likely reduces intrapreneurship through creating deficits in the work environment necessary for intrapreneurship to flourish.

Figure 1.

The relationship between CSE and intrapreneurship mediated by incivility and perceived organisational support.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

A total of 415 working individuals (169 males, 243 females, 3 participants identified as “other” or “preferred not to say”) 18 to 71 years old (M = 33.01 years, SD = 11.67) took part in the study. Five cases had missing data, and the final sample size was 410. Participants worked across a wide range of occupations, including finance and insurance (18.3%), retail (16.1%), hospitality (12.0%), or health and community services industries (11.3%). The remaining 42.3% worked in various industries ranging from education to government and administration. Most participants held bachelor (54.2%) or postgraduate qualifications (14.2%). Job tenure ranged from less than one year to over 26 years (M = 5.32 years, SD = 4.91), with 60.0% of participants working in nonsupervisory or nonmanagement roles.

Participants were recruited from three sources: Mechanical Turk (MTurk), an online crowdsourcing marketplace, LinkedIn, and first-year university psychology students. Participants recruited through MTurk were paid USD 2.50 to complete the online survey, with those recruited from LinkedIn not receiving any compensation. University students were eligible for course credit. Data were gathered via an online survey where participants were asked to complete a series of published psychometric questionnaires administered via Qualtrics, an online survey platform. In addition to the focal variables, control variables including gender, age, employment status, educational attainment, tenure, and management status, were also collected.

2.2. Measures

Intrapreneurship was measured using an adapted version of the intrapreneurship scale developed by De Jong et al. [13,50]. This is a nine-item questionnaire that asks respondents to rate their intrapreneurship behaviours, specifically innovativeness, proactiveness and risk-taking. An example item includes: “I search out new techniques, technologies and/or product ideas”. Responses were recorded using a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very often). Cronbach’s alpha was .90.

The core self-evaluation scale (CSES) [34] was used to measure CSE. The CSES consists of 12 items answered according to a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). A sample item is: “I am confident I get the success I deserve in life”. The CSES is a direct and reliable measure of CSE, is well suited for research and screening purposes [51] and offers good convergent and divergent validity as demonstrated by strong correlations with global self-esteem, generalised self-efficacy, locus of control, and neuroticism [34]. Cronbach’s alpha was .90.

Perceived organisational support was measured using two factors from the Alpkan et al. [1] organisational support questionnaire, which was adapted from items developed by Kuratko et al. [52]. The first factor, “management support for idea generation” (management support), refers to the encouragement of entrepreneurial idea generation and development, with the second factor, “tolerance for risk-taking”, indicating recognition of risk-taking intrapreneurs even if they fail. A sample management support item is: “Developing one’s own idea is encouraged for the improvement of the organisation”. A sample tolerance for risk-taking item is: “Individual risk-takers are often recognised for their willingness to champion new projects, whether eventually successful or not”. These factors each consisted of four items, answered using a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Cronbach’s alphas of .85 and .89 were found for the management support and tolerance for risk-taking subfactors, respectively.

Incivility was measured using the workplace incivility scale (WIS) [53], which assesses employees’ experiences of incivility via 10 questions. A sample item is: “During the past year, have you been in a situation where your supervisor or co-workers made demeaning, rude or derogatory remarks about you?”. Questions were rated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (once or twice a year) to 5 (everyday) relating to the frequency of uncivil behaviours. Cronbach’s alpha for this factor was .90.

2.3. Analyses

To test the hypotheses, including (H4) that incivility and perceived organisational support would mediate the relationship between CSE and intrapreneurship, a double mediation was run using the PROCESS macro v2.16 [54] Model 6 in SPSS v.25. Bootstrapping was set at 10,000 replications [55], which generated total, direct and indirect effects, testing whether the indirect effect of CSE on intrapreneurship was mediated by incivility and perceived organisational support. In this model, CSE was the predictor, incivility and perceived organisational support were the mediators and intrapreneurship was the criterion. Dummy-coded gender, employment status, educational attainment and management status, as well as age were added to the model as covariates.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptives

Descriptive statistics and intercorrelations for all variables are presented in Table 1. As expected, CSE, perceived organisational support and intrapreneurship were all significantly correlated. Incivility was significantly negatively correlated with CSE and perceived organisational support, but not with intrapreneurship. Intrapreneurship, CSE and perceived organisational support were also significantly positively correlated with age, working status and management status. Intrapreneurship and CSE were also significantly positively correlated with tenure.

Table 1.

Means, standard deviations and intercorrelations between research variables (n = 410).

3.2. Hypothesis Testing

A set of multiple regression analyses were conducted to test for serial mediation and the results are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Serial mediation model of CSE on intrapreneurship through incivility and perceived organisational support.

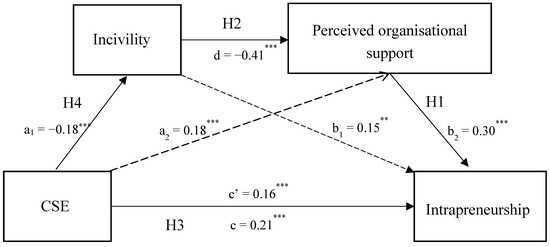

The total effect as outlined in Table 2 reflected the overall explanation of intrapreneurship through CSE. Examination of the individual path coefficients in Figure 2 shows that the path representing the relationship between CSE, and incivility (path a1) was statistically significant and negative, t(402) = −6.33, p < 0.001, while the path representing the relationship between CSE and organisational support (path a2) was statistically significant and positive, t(401) = 4.29, p < 0.001. The relationship between incivility and intrapreneurship (path b1) was statistically significant and positive, t(400) = 2.23, p = 0.026, similar to the relationship between organisational support and intrapreneurship (path b2), t(400) = 6.58, p < 0.001 (supporting H1). These results suggest that greater levels of CSE are related to a decrease in incivility and an increase in perceived organisational support, which in turn relates to an increase in intrapreneurship.

Figure 2.

The serial mediating effect of incivility and perceived organisational support on the relationship between CSE and intrapreneurship. Note: All presented effects are unstandardised; a is the effect of CSE on mediators; b is effect of mediators on intrapreneurship; c is total effect of CSE on intrapreneurship; c’ is direct effect of CSE on intrapreneurship; d is effect of incivility on intrapreneurship. ** p < .01, *** p < .001.

The relationship between incivility and perceived organisational support (path d) was also statistically significant but negative, t(401) = −5.99, p < 0.001, proposing that higher levels of incivility are related to decreased levels of perceived organisational support. The path representing the relationship between CSE and intrapreneurship (i.e., path c) was significant, t(402) = 5.46, p < 0.001 (supporting H3). However, in the presence of the mediators, the effect of CSE on intrapreneurship (i.e., path c’) was reduced, yet remained significant, t(400) = 4.07, p < 0.001. Therefore, mediation was confirmed due to the reduction in the effect size of CSE on intrapreneurship with the inclusion of incivility and perceived organisational support as mediators (supporting H4).

The total effect of CSE on intrapreneurship was 20.93%, of which 15.95% was attributed to the direct effect of CSE on intrapreneurship. The overall effect through the mediators was significant with an effect size of 4.98%, of which 5.39% was due to perceived organisational support as a single mediator, and −2.68% due to incivility as a single mediator (supporting H2). As serial mediators, incivility and perceived organisational support accounted for 2.27% of the indirect effect. Results show that 10.85% of the total effect of CSE on intrapreneurship is accounted for by the indirect serial effect through incivility and perceived organisational support.

4. Discussion

4.1. Mediation Effects

Table 3 lists the hypotheses tested and the outcomes based on the statistical analyses of the data.

Table 3.

Summary of hypotheses.

As can be seen in Table 3 and Figure 2, as a single mediator, incivility significantly mediated the relationship between CSE and intrapreneurship. This finding aligns with current research relating CSE to workplace incivility, showing that employees who possess high self-efficacy are better equipped to cope with the negative effects of workplace incivility [56]. The results of the current work extend prior research conducted on abusive supervision and creativity, with CSE as a moderator of abusive supervision [57]. Both the current study and the research conducted by Zhang et al. [42,57] identifies CSE as a potential protective factor against interpersonal mistreatment. However, the current study illustrates the relationship through the lens of CSE and the approach/avoidance motivation framework, suggesting that individuals with higher levels of CSE are inherently less sensitive to the adverse effects of incivility, thereby reducing any potential damage. Overall, these results establish a more comprehensive understanding of how CSE, working through incivility, predicts intrapreneurship.

As a single mediator, perceived organisational support was a significant and more powerful mediator of the relationship between CSE and intrapreneurship than incivility. Although this specific mediating relationship has not been examined before, previous research exploring organisational support as a function of intrapreneurship has found comparable results using a similar employee-oriented method, revealing an indirect effect of work context on intrapreneurship [58]. These findings offer a practical application of the approach/avoidance motivation framework, illustrating how CSE shapes how individuals interpret their work context in terms of the organisational support they experience.

It was further found that incivility and perceived organisational support would serially mediate the relationship between CSE and intrapreneurship. These results indicate that although CSE is likely to influence an individual’s levels of incivility, which in turn reflects how they interpret organisational support, which then affects their capacity to exhibit intrapreneurship, it is to a relatively small degree. This finding is consistent with the approach/avoidance motivation framework, which posits that individuals high in CSE are less sensitive to negative stimuli such as incivility, where the intent can be ambiguous. They are also more sensitive to positive stimuli such as organisational support in the form of available management support and tolerance for risk-taking, resulting in an increase in intrapreneurship. This relationship has not been previously explored, and despite its small effect size, this finding contributes to our current understanding of the critical role CSE plays in how we perceive and interpret our work environment and how our self-views shape resulting behaviours.

4.2. Intrapreneurship and Incivility

Interestingly, instead of incivility negatively relating to intrapreneurship, a significant positive relationship was found. In line with prior research [13], no significant correlation was found between incivility and intrapreneurship. However, when added to the regression model, incivility positively predicted intrapreneurship, but without the inclusion of the other predictors, no relationship was observed. As the analyses also revealed significant correlations between incivility, CSE and perceived organisational support, incivility may be acting as a suppressor variable. Hierarchical regression was used to test this premise. When added to the regression equation, incivility increased the predictability of CSE and perceived organisational support in determining intrapreneurship, indicating the likelihood of shared variance between incivility and other predictors of intrapreneurship. However, because the VIF statistics for each variable (including incivility) ranged from 1.04 to 1.2, all well below the 5 cut-off [59], it is still appropriate to include incivility, despite it being a potential suppressor variable, in the regression model.

Incivility is low in intensity and can be ambiguous in its intent [27]. Therefore, due to its low intensity and controlling for other factors, incivility may not have a direct relationship to intrapreneurship. Andersson and Pearson [27] stated that incivility could be attributed to instigator ignorance, target misinterpretation or hypersensitivity. This aligns with the approach/avoidance motivation framework to describe the effects of CSE on intrapreneurship, such that an individual low in CSE is more likely to be sensitive to the effects of uncivil behaviour, which will in turn influence intrapreneurship. However, controlling for CSE, incivility may not be sufficiently intense to have a direct effect on intrapreneurship.

4.3. Intrapreneurship and Perceived Organisational Support

The results showed that perceived organisational support was positively associated with intrapreneurship. This is consistent with existing research, finding similar relationships between management support and intrapreneurship [1,20] and tolerance for risk-taking and intrapreneurship [2,13]. Management support is essential to promote intrapreneurship as it serves as a reliable indicator that management is receptive to new ideas and innovations. This support can shape and extend the parameters of existing organisational policies and procedures, paving the way for further innovation and formalisation of future organisational practices. Management support also encourages potential intrapreneurs to realise opportunities, and in doing so, creates an environment of trust where employees feel safe to take risks in order to develop ideas that ultimately benefit the organisation. This is particularly important when ideas fail, as a lack of confidence by management in these ambiguous circumstances is likely to have an inhibitory effect on future innovation [26].

4.4. Intrapreneurship and Core Self-Evaluation

The results are the first to demonstrate an empirical link between CSE and intrapreneurship and build on the cumulative knowledge that facets of CSE, such as self-efficacy [15,41], self-esteem and risk-taking [60], are key to fostering creative competencies directed at the creation of new ideas and/or ventures. This also aligns with relevant CSE theory proposing that CSE can have a direct influence on outcomes through emotional generalisation [37], suggesting that one’s self-views are likely to have a spillover effect into other domains, in this case, intrapreneurship.

4.5. Theoretical and Practical Implications

The current work highlights the practical utility of the approach/avoidance motivation framework. To date, this framework has been used to explain both CSE and workplace aggression but not how CSE relates to organisational support or intrapreneurship. Individuals who score high in CSE possess a stronger approach disposition and are more likely to interpret available organisational support such as tolerance for risk-taking positively, and as a result, they are more likely to engage in intrapreneurship. In contrast, low CSE individuals are more influenced by unfavorable work environments [38], and because of their low self-esteem and external locus of control, they are likely to interpret the same tolerance for risk-taking as threatening because of the potential for failure. This finding illustrates the importance of individual traits such as CSE when researching organisational behaviour.

The findings of the current research also have implications for organisations. To promote intrapreneurship, organisations need to take action such as using personality testing at recruitment to better select those employees high in CSE (or a similar approach-focused trait) to ensure that employees possess the personality traits shown to have a significant impact on intrapreneurship, However, employee selection alone is not enough to promote intrapreneurship. The research suggests that work context also affects intrapreneurship. Employee perceptions of key workplace factors such as workplace encouragement of creativity, autonomy, resources, work pressures and organisational impediments play some role in promoting intrapreneurship [7,60]. Therefore, formally designed workplace policies and practices aimed at changing both formal and informal work environments in terms of a more supportive culture where risk-taking is embraced will also impact the level of intrapreneurship within organisations.

4.6. Limitations and Future Directions

Like all research, the findings of the current research should be interpreted within context. First, the study relied on self-reported data. Although the use of self-reported data is common in organisational and management research and is particularly appropriate in the measurement of personality [61], it is acknowledged that self-report measures have some limitations in comparison with objective measures.

A second potential limitation was the use of a cross-sectional design, making it impossible to infer causality. It is possible that reverse causality could be occurring, with the expression of intrapreneurship causing organisations to be more supportive, resulting in increased employee CSE. The relationship may also be bidirectional, with individual and workplace factors both causes and consequences of intrapreneurship. However, based on the relevant theory and empirical research to date, the proposed model offers a fitting account of relationships explored.

5. Conclusions

The current research highlights the importance of organisations being cognisant of how individual and organisational factors interact to impact intrapreneurship. Initiatives to cultivate intrapreneurship will be more impactful when combined with strategies that improve employee CSE. CSE plays a significant role in determining to what extent intrapreneurship will be exhibited and acts as a lens with respect to how facilitative or inhibitory employees interpret their work environment, with respect to workplace incivility and organisational support. This research makes an important new contribution to the literature providing insights into how individual and organisational factors impact intrapreneurship.

Author Contributions

All authors made substantial contributions to the conception of the work. M.R. and E.G. were responsible for the acquisition of the data. M.R. and E.G. analysed the data. M.R., E.G. and J.D. made substantial contributions to the interpretation of the data. M.R. drafted the work, and all other authors critically revised the work for important intellectual content. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Griffith Business School, Centre for Work, Organisation and Wellbeing.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Australian Code for the Responsible Conduct of Research (2018) and approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of Griffith University (GU Ref: 2019/347).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from the authors and can be provided upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Alpkan, L.; Bulut, C.; Gunday, G.; Ulusoy, G.; Kilic, K. Organizational support for intrapreneurship and its interaction with human capital to enhance innovative performance. Manag. Decis. 2010, 48, 732–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoncic, J.A.; Antoncic, B.; Li, Z. Creativity of the entrepreneur, intrapreneurship, and the growth of small and medium-sized enterprises: Evidence from China. Chin. Bus. Rev. 2018, 17, 336–341. [Google Scholar]

- Pandey, J.; Gupta, M.; Hassan, Y. Intrapreneurship to engage employees: Role of psychological capital. Manag. Decis. 2020, 59, 1525–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aina, Q.; Solikin, I. Entrepreneurship and intrapreneurship: How supporting corporate performance. Rev. Integr. Bus. Econ. Res. 2020, 9, 288–297. [Google Scholar]

- Feldmann, A. The 5 P’s to success in intrapreneurial programs. Z. Gesamte Genoss. 2021, 71, 5–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenow-Gerhard, J. Lessons learned—Configuring innovation labs as spaces for intrapreneurial learning. Stud. Contin. Educ. 2021, 43, 244–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanka, C. An individual-level perspective on intrapreneurship: A review and ways forward. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2019, 13, 919–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Letsie, T.M. Barriers of intraprenurship practice at South African public hospitals: Perspectives of unit nurse managers. Glob. J. Health Sci. 2021, 13, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuther, K.; Borodzicz, E.P.; Schumann, C.-A. Identifying barriers to intrapreneurship. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Engineering, Technology and Innovation (ICE/ITMC), Stuttgart, Germany, 17–20 June 2018; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Antoncic, B. Entrepreneurship/intrapreneurship, personality correlates of. In The Wiley Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences: Personality Processes and Individual Differences; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 143–147. [Google Scholar]

- Neessen, P.C.; Caniels, M.C.; Vos, B.; De Jong, J.P. The intrapreneurial employee: Toward an integrated model of intrapreneurship and research agenda. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2018, 15, 545–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Åmo, B.W.; Kolvereid, L. Organizational strategy, individual personality and innovation behavior. J. Enterp. Cult. 2005, 13, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yariv, I.; Galit, K. Can incivility inhibit intrapreneurship? J. Entrep. 2017, 26, 27–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliot, A.J.; Thrash, T.M. Approach-avoidance motivation in personality: Approach and avoidance temperaments and goals. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 82, 804–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alessio, F.; Finstad, G.L.; Giorgi, G.; Lulli, L.G.; Traversini, V.; Lecca, L.I. Intrapreneurial self-capital: An overview of an emergent construct in organizational behaviour. Calitatea 2019, 20, 156–162. [Google Scholar]

- Doern, R.; Williams, N.; Vorley, T. Special issue on entrepreneurship and crises: Business as usual? An introduction and review of the literature. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2019, 31, 400–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Serrano, M.H.; González García, R.J.; Pérez Campos, C. Entrepreneurial and intrapreneurial intentions of sports science students: What are their determinant variables? J. Phys. Educ. Sport 2018, 18, 1363–1372. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberger, R.; Huntington, R.; Hutchison, S.; Sowa, D. Perceived organizational support. J. Appl. Psychol. 1986, 71, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badoiu, G.-A.; Segarra-Ciprés, M.; Escrig-Tena, A.B. Understanding employees’ intrapreneurial behavior: A case study. Pers. Rev. 2020, 49, 1677–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouchane, R.; Fernet, C.; Austin, S.; Zouaoui, S.K. Organizational support and intrapreneurial behavior: On the role of employees’ intrapreneurial intention and self-efficacy. J. Manag. Organ. 2021, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelbrecht, A.; Samuel, O.M. The effect of transformational leadership on intention to quit through perceived organisational support, organisational justice and trust. S. Afr. J. Econ. Manag. Sci. 2019, 22, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reibenspiess, V.; Drechsler, K.; Eckhardt, A.; Wagner, H.-T. Tapping into the wealth of employees’ ideas: Design principles for a digital intrapreneurship platform. Inf. Manag. 2020, 103287, 103287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guven, B. The integration of strategic management and intrapreneurship: Strategic intrapreneurship from theory to practice. Bus. Econ. Res. J. 2020, 11, 229–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekingen, E.; Ekemen, M.A.; Yildiz, A.; Korkmazer, F. The effect of intrapreneurship and organizational factors on the innovation performance in hospital. RCIS 2018, 62, 196–219. [Google Scholar]

- Hisrich, R.D. Entrepreneurship/intrapreneurship. Am. Psychol. 1990, 45, 209–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoncic, J.A.; Antoncic, B. Need for achievement of the entrepreneur, intrapreneurship, and the growth of companies in tourism and trade. Mod. Manag. Tools Econ. Tour. Sect. Present Era 2018, 259–265. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson, L.M.; Pearson, C.M. Tit for tat? The spiraling effect of incivility in the workplace. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1999, 24, 452–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-H.; Chen, H.-T. Relationships among workplace incivility, work engagement and job performance. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2020, 3, 415–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namin, B.H.; Øgaard, T.; Røislien, J. Workplace incivility and turnover intention in organizations: A meta-analytic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jawahar, I.; Schreurs, B. Supervisor incivility and how it affects subordinates’ performance: A matter of trust. Pers. Rev. 2018, 47, 709–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Zhou, Z.E.; Che, X.X. Effect of workplace incivility on OCB through burnout: The moderating role of affective commitment. J. Bus. Psychol. 2019, 34, 657–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.-E.; Chen, Y.; He, W.; Huang, J. Supervisor incivility and millennial employee creativity: A moderated mediation model. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2019, 47, e8365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, R.M. Social exchange theory. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1976, 2, 335–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, T.A.; Erez, A.; Bono, J.E.; Thoresen, C.J. The core self-evaluations scale: Development of a measure. Pers. Psychol. 2003, 56, 303–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bono, J.E.; Judge, T.A. Core self-evaluations: A review of the trait and its role in job satisfaction and job performance. Eur. J. Personal. 2003, 17, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Gully, S.M.; Eden, D. Validation of a new general self-efficacy scale. Organ. Res. Methods 2001, 4, 62–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Judge, T.A.; Locke, E.A.; Durham, C.C.; Kluger, A.N. Dispositional effects on job and life satisfaction: The role of core evaluations. J. Appl. Psychol. 1998, 83, 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kacmar, K.M.; Collins, B.J.; Harris, K.J.; Judge, T.A. Core self-evaluations and job performance: The role of the perceived work environment. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 1572–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Williams, M.; Gardiner, E. The power of personality at work: Core self-evaluations and earnings in the United Kingdom. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2018, 28, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, E.J.; Fitzsimmons, J.R. Intrapreneurial intentions versus entrepreneurial intentions: Distinct constructs with different antecedents. Small Bus. Econ. 2013, 41, 115–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bee Seok, C.; Abd Hamid, H.S.; Ismail, R. Psychometric properties of the intrapreneurial self-capital scale in Malaysian university students. Sustainability 2019, 11, 881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, Y.; Sun, J.-M.J.; Lin, C.-H.V.; Ren, H. Linking core self-evaluation to creativity: The roles of knowledge sharing and work meaningfulness. J. Bus. Psychol. 2020, 35, 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gray, J.A. A critique of Eysenck’s theory of personality. In A Model for Personality; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1981; pp. 246–276. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, C.-H.; Ferris, D.L.; Johnson, R.E.; Rosen, C.C.; Tan, J.A. Core self-evaluations: A review and evaluation of the literature. J. Manag. 2012, 38, 81–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferris, L.D.; Yan, M.; Lim, V.K.G.; Chen, Y.; Fatimah, S. An approach-avoidance framework of workplace aggression. Acad. Manag. J. 2016, 59, 1777–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, C.M.; Andersson, L.M.; Porath, C.L. Workplace incivility. In Counterproductive Work Behavior: Investigations of Actors and Targets; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2005; pp. 177–200. [Google Scholar]

- Wetzel, E.; Grijalva, E.; Robins, R.W.; Roberts, B.W. You’re still so vain: Changes in narcissism from young adulthood to middle age. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2020, 119, 479–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Shalley, C.E.; Zhou, J.; Oldham, G.R. The effects of personal and contextual characteristics on creativity: Where should we go from here? J. Manag. 2004, 30, 933–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Geldart, S.; Langlois, L.; Shannon, H.S.; Cortina, L.M.; Griffith, L.; Haines, T. Workplace incivility, psychological distress, and the protective effect of co-worker support. Int. J. Workplace Health Manag. 2018, 11, 96–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jong, J.; Parker, S.; Wennekers, S.; Wu, C. Corporate Entrepreneurship at the Individual Level: Measurement and Determinants; EIM: Zoetermeer, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 3–27. [Google Scholar]

- Zenger, M.; Körner, A.; Maier, G.W.; Hinz, A.; Stöbel-Richter, Y.; Brähler, E.; Hilbert, A. The core self-evaluation scale: Psychometric properties of the German version in a representative sample. J. Personal. Assess. 2015, 97, 310–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuratko, D.F.; Hornsby, J.S.; Bishop, J.W. Managers’ corporate entrepreneurial actions and job satisfaction. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2005, 1, 275–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortina, L.M.; Magley, V.J.; Williams, J.H.; Langhout, R.D. Incivility in the workplace: Incidence and impact. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2001, 6, 64–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, A.F. Process; The Ohio State University: Columbus, OH, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Clercq, D.; Haq, I.U.; Azeem, M.U. Self-efficacy to spur job performance: Roles of job-related anxiety and perceived workplace incivility. Manag. Decis. 2018, 56, 891–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Kwan, H.K.; Zhang, X.; Wu, L.-Z. High core self-evaluators maintain creativity: A motivational model of abusive supervision. J. Manag. 2014, 40, 1151–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigtering, J.P.; Weitzel, U. Work context and employee behaviour as antecedents for intrapreneurship. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2013, 9, 337–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Akinwande, M.O.; Dikko, H.G.; Samson, A. Variance inflation factor: As a condition for the inclusion of suppressor variable (s) in regression analysis. Open J. Stat. 2015, 5, 754–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gawke, J.C.; Gorgievski, M.J.; Bakker, A.B. Measuring intrapreneurship at the individual level: Development and validation of the Employee Intrapreneurship Scale (EIS). Eur. Manag. J. 2019, 37, 806–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulhus, D.L.; Vazire, S. The self-report method. Handb. Res. Methods Personal. Psychol. 2007, 1, 224–239. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).