Taking a Step Back? Expatriation Consequences on Women in Dual-Career Couples in the Gulf

Abstract

:1. Introduction

RQ: How is the career capital of expatriate women affected by working in the Middle East as part of a DCC?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Dual-Career Couples and Their Career Strategies

2.2. Expatriate Women’s Career Capital in a Middle Eastern Contextual Setting

3. Methods

3.1. Sample

3.2. Interview Guide and Procedure

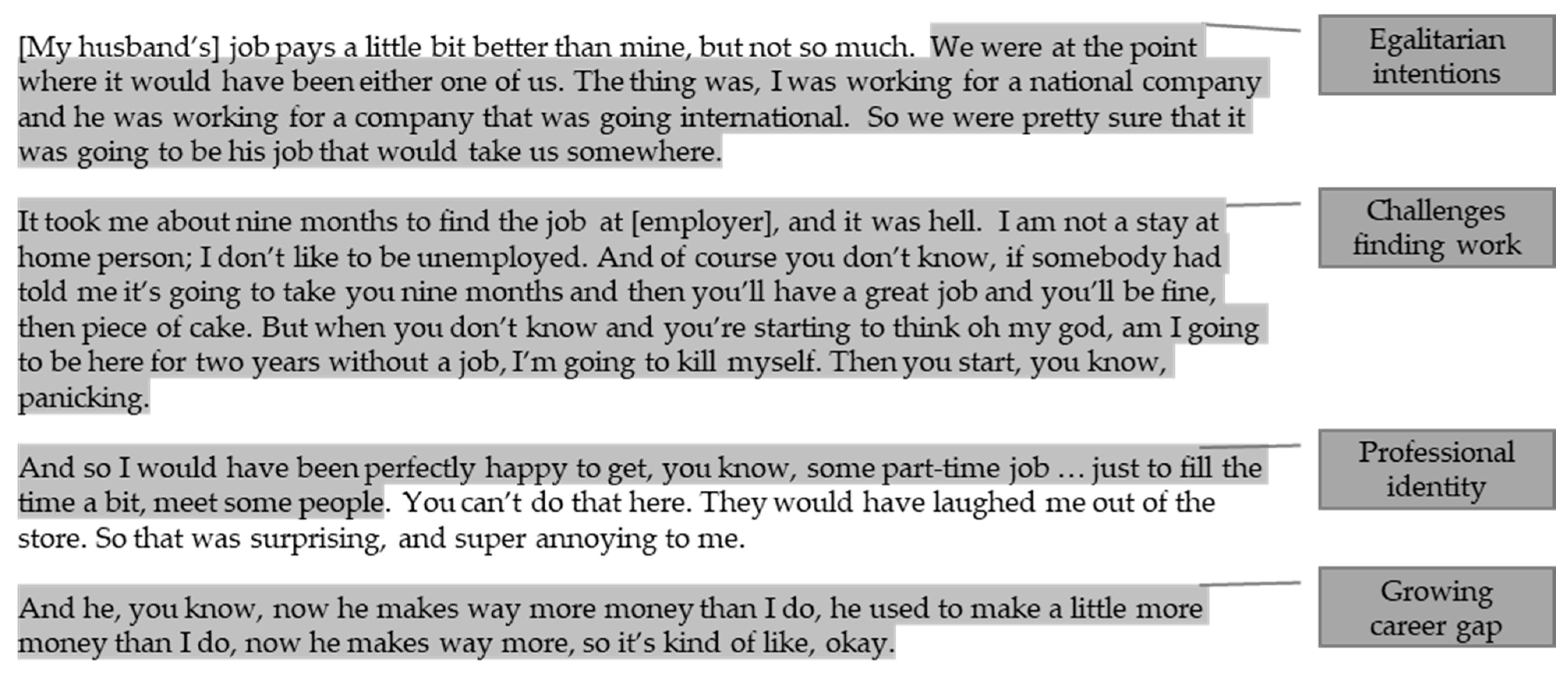

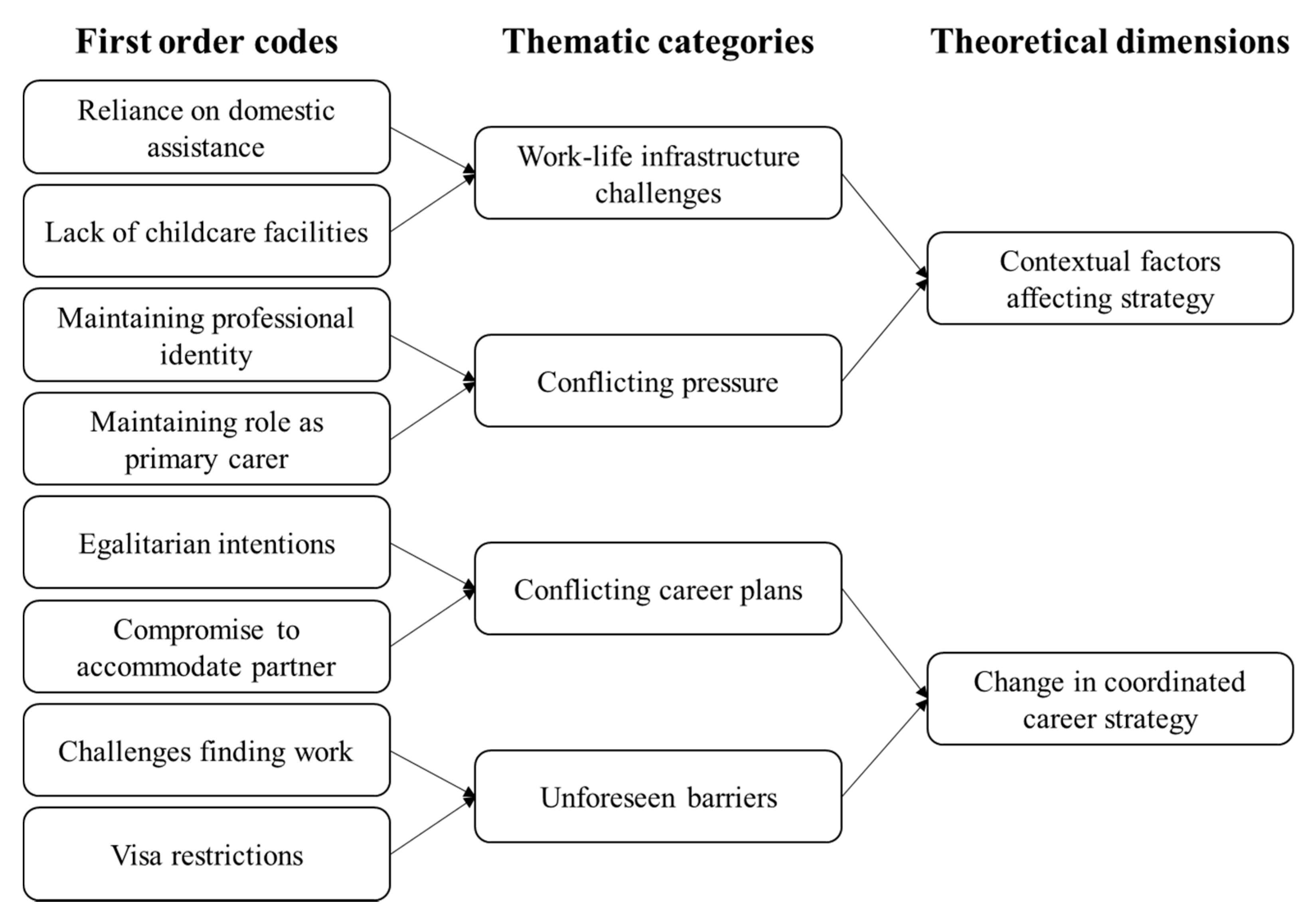

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Conflicting Career Plans

‘I think yes if I had said I sacrificed anything it would be when I resigned from [my previous employer] and worked in Kuwait. It was a pretty big step back, but again it was better that we were together and that we were both in Kuwait rather than travelling every week. So it was for the right reasons.’

‘[My husband’s] job paid a little bit better than mine, but not much. We were at the point where it would have been either one of us. I left a really, really good job, that in the midst of my darkest days I regretted horribly. It took me about nine months to find the job at AirCo, and it was hell. I am not a stay-at-home person; I don’t like to be unemployed.’

‘It took a serious toll on my confidence, and my ego. The problem was I was applying primarily for jobs that you saw on the web, because I didn’t have a network, I didn’t have anything established. I ended up getting my job because I started playing mah-jong, I was talking about my job search and [my friend said her] husband works at AirCo, and voila, two months later I have a job.’

‘Applying was just disastrous. I think I applied for a million jobs and didn’t hear anything. No confirmation they’d received anything, and it was quite soul destroying. Or you’d find an advert that seemed alright, and then it was like, but you need to be on your husband’s visa.’

4.2. Work–Life Infrastructure Challenge

‘And Bristol was, for [my husband], a better career move. Now he makes way more money than I do; he used to make a little more money than I do, now he makes way more.’

‘When you’ve only really got your husband’s work friends as friends, you don’t have your own life really… I think at that point it was just like, I will take any money, I don’t care, I just need to do something.’

‘[My husband] is going to be quite lucky, he’s found himself a role in the UK business. He’s going to be working in a team where there’s international travel and the team that he worked with to establish the project in Qatar five years ago. I haven’t; it’s difficult knowing where to go’.

4.3. Unforeseen Barriers

‘They talk about the glass ceiling; they talk about women not being equal in the workforce. I’ve been a senior director now, in my last job in California… I’d never felt that being female caused me any disadvantages… I think… I fall into the trap that women here do, and I am less aggressive and assertive as my male counterparts are.’

‘You don’t see a lot of women at the executive level in many of the companies across the UAE. [My husband] wants to progress his career further, and I don’t know if I’ll get much further in [my current employer]. I just think that there’s a little bit of a glass ceiling. A lot of people in the Middle East who work are men, so therefore by default there ends up being boys’ clubs, whether you like it or not. My male colleague is more comfortable talking to another male colleague rather than talking to me.’

‘If you have children you have to have a maid essentially because they don’t really have any childcare, particularly before school and after school. It’s very difficult to have two people in a family with young children who are both careers-driven, so one of you does have to step back a bit in order to maintain family unity. I never wanted to devolve my responsibility as a mother to someone else.’

‘I didn’t really develop my career in any way. I was head of department in the UK and then I took a job out in the Middle East as just a plain main pay scale teacher. I didn’t progress my career, and by the end of the experience I hadn’t gone backwards either, so I remained at the same place. And in teaching, your experience in the British education system is actually more important than experience abroad, so if I’d have stayed out much longer than four years then I may not have been able to get a job when I got back into the UK.’

4.4. Prioritising Women’s Careers

It’s given me what I want. I wanted to develop this networking amongst different departments and being in the project management office is clearly working with everybody. I had a very significant involvement in the commercial and financial management of the work that we are doing here, which is something, a box that I needed to tick in my experience, which is great.

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Practical Implications

6.2. Limitations and Future Research

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Caligiuri, P.; Bonache, J. Evolving and enduring challenges in global mobility. J. World Bus. 2016, 51, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shortland, S.; Perkins, S.J. Long-term assignment reward (dis)satisfaction outcomes: Hearing women’s voices. J. Glob. Mobil. 2016, 4, 225–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Varma, A.; Russell, L. Women and expatriate assignments: Exploring the role of perceived organizational support. Empl. Relat. 2016, 38, 200–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gripenberg, P.; Niemistö, C.; Alapeteri, C. Ask us equally if we want to go. J. Glob. Mobil. 2013, 1, 287–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Känsälä, M.; Mäkelä, L.; Suutari, V. Career coordination strategies among dual career expatriate couples. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014, 26, 2187–2210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GCC Statistical Centre. Labour Force (15 Year and above) by Nationality and Gender in GCC Countries, 2011–2015. Available online: https://gccstat.org/en (accessed on 22 June 2018).

- Baruch, Y.; Forstenlechner, I. Global careers in the Arabian Gulf: Understanding motives for self-initiated expatriation of the highly skilled, globally mobile professionals. Career Dev. Int. 2017, 22, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, L.J.; Rickett, B. The lived experiences of foreign women: Influences on their international working lives. Gend. Work Organ. 2018, 25, 343–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andresen, M.; Bergdolt, F.; Margenfeld, J.; Dickmann, M. Addressing international mobility confusion—developing definitions and differentiations for self-initiated and assigned expatriates as well as migrants. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014, 25, 2295–2318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Haak-Saheem, W.; Brewster, C. ‘Hidden’ expatriates: International mobility in the United Arab Emirates as a challenge to current understanding of expatriation. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2017, 27, 423–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roos, H. In the rhythm of the global market: Female expatriates and mobile careers: A case study of Indian ICT professionals on the move. Gend. Work Organ. 2013, 20, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miano, P.; Salerno, A.; Merenda, A.; Ciulla, A. Whose Turn Is It? Problems of Reconciling Family and Work in Dual-Career Couples. Int. J. Humanit. Soc. Stud. 2015, 3, 147–153. [Google Scholar]

- van der Velde, M.E.G.; Jansen, P.G.W.; Bal, P.M.; van Erp, K.J. Dual-earner couples’ willingness to relocate abroad: The reciprocal influence of both partners’ career role salience and partner role salience. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2016, 26, 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tharenou, P. Self-initiated expatriates: An alternative to company-assigned expatriates? J. Glob. Mobil. 2013, 1, 336–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayerhofer, H.; Hartmann, L.C.; Michelitsch-Riedl, G.; Kollinger, I. Flexpatriate assignments: A neglected issue in global staffing. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2004, 15, 1371–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baluku, M.M.; Löser, D.; Otto, K.; Schummer, S.E. Career mobility in young professionals: How a protean career personality and attitude shapes international mobility and entrepreneurial intentions. J. Glob. Mobil. 2018, 16, 102–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suutari, V.; Brewster, C.; Mäkelä, L.; Dickmann, M.; Tornikoski, C. The effect of international work experience on the career success of expatriates: A comparison of assigned and self-initiated expatriates. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018, 57, 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Harvey, M.; Novicevic, M.; Breland, J.W. Global dual-career exploration and the role of hope and curiosity during the process. J. Manag. Psychol. 2009, 24, 178–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slobodin, O. The Voice of Trailing Women in the Decision to Relocate: Is It Really a Choice? In People’s Movements in the 21st Century—Risks, Challenges and Benefits; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2017; pp. 261–273. Available online: https://www.intechopen.com/books/people-s-movements-in-the-21st-century-risks-challenges-and-benefits/the-voice-of-trailing-women-in-the-decision-to-relocate-is-it-really-a-choice- (accessed on 18 June 2021).

- Mäkelä, L.; Suutari, V.; Mayerhofer, H. Lives of female expatriates: Work-life balance concerns. Gend. Manag. Int. J. 2011, 26, 256–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, S. Career capital in global Kaleidoscope Careers: The role of HRM. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2016, 27, 681–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kierner, A.; Suutari, V. Repatriation of international dual-career couples. Thunderbird Int. Bus. Rev. 2017, 60, 885–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laroche, L.; Bing, C.M. Negotiating Expatriate Packages. Available online: http://www.itapintl.com/index.php/about-us/articles/negotiating-expatriate-packages (accessed on 10 March 2017).

- Fischlmayr, I.C.; Puchmüller, K.M. Married, mom and manager—How can this be combined with an international career? Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2016, 27, 744–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shortland, S. The ‘expat factor’: The influence of working time on women’s decisions to undertake international assignments in the oil and gas industry. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2015, 26, 1452–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidani, Y.M.; Al Ariss, A. Institutional and corporate drivers of global talent management: Evidence from the Arab Gulf region. J. World Bus. 2014, 49, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herod, A.; Rainnie, A.; Mcgrath-Champ, S. Working space: Why incorporating the geographical is central to theorizing work and employment practices. Work Employ. Soc. 2007, 21, 247–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metcalfe, B.D.; Rees, C.J. Gender, globalization and organization: Exploring power, relations and intersections. Equal. Divers. Incl. Int. J. 2010, 29, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennekam, S.; Tahssain-Gay, L.; Syed, J. Contextualising diversity management in the Middle East and North Africa: A relational perspective. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2017, 27, 459–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metcalfe, B.D. Gender and human resource management in the Middle East. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2007, 18, 54–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchings, K.; Lirio, P.; Metcalfe, B.D. Gender, globalisation and development: A re-evaluation of the nature of women’s global work. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2012, 23, 1763–1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bardot, S. Background on Work Life in the United Arab Emirates and Other Gulf Countries (Gulf Cooperation Council). Compens. Benefits Rev. 2013, 45, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bel-Air, F. Demography, Migration, and the Labour Market in the UAE. Available online: http://cadmus.eui.eu/bitstream/handle/1814/36375/GLMM_ExpNote_07_2015.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 21 May 2021).

- Syed, J.; Ali, F.; Hennekam, S. Gender equality in employment in Saudi Arabia: A relational perspective. Career Dev. Int. 2018, 23, 163–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, J.K.; Ridgway, M. Contextualizing privilege and disadvantage: Lessons from women expatriates in the Middle East. Organization 2019, 26, 391–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, T. Women’s Experience of Workplace Interactions in Male-Dominated Work: The Intersections of Gender, Sexuality and Occupational Group. Gend. Work Organ. 2016, 23, 348–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthur, M.B.; Defillippi, R. The boundaryless career: A competency-based perspective. J. Organ. Behav. 1994, 15, 307–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.; Hooley, T.; Wond, T. Building career capital: Developing business leaders’ career mobility. Career Dev. Int. 2020, 25, 445–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickmann, M.; Doherty, N. Exploring the career capital impact of international assignments within distinct organizational contexts. Br. J. Manag. 2008, 19, 145–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suutari, V.; Mäkelä, K. The career capital of managers with global careers. J. Manag. Psychol. 2007, 22, 628–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, J.K.; Scurry, T. Career capital development of self-initiated expatriates in Qatar: Cosmopolitan globetrotters, experts and outsiders. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014, 25, 190–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Berry, D.P.; Bell, M.P. “Expatriates”: Gender, race and class distinctions in international management. Gend. Work Organ. 2012, 19, 10–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Waqfi, M.A.; Al-Faki, I.A. Gender-based differences in employment conditions of local and expatriate workers in the GCC context: Empirical evidence from the United Arab Emirates. Int. J. Manpow. 2015, 36, 397–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridgway, M. Hidden Inequalities of the Expatriate Workforce. In Hidden Inequalities in the Workplace; Caven, V., Nachimas, S., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 303–330. [Google Scholar]

- Sidani, Y.M.; Konrad, A.; Karam, C.M. From female leadership advantage to female leadership deficit: A developing country perspective. Career Dev. Int. 2015, 20, 273–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michailova, S.; Hutchings, K. Critiquing the marginalised place of research on women within international business. Crit. Perspect. Int. Bus. 2016, 12, 348–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickmann, M.; Suutari, V.; Brewster, C.; Mäkelä, L.; Tanskanen, J.; Tornikoski, C. The career competencies of self-initiated and assigned expatriates: Assessing the development of career capital over time. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018, 29, 2353–2371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, M.N.K. Choosing Research Participants. In Qualitative Organizational Research; Symon, G., Cassell, C., Eds.; Sage Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2016; pp. 35–52. [Google Scholar]

- Ridgway, M.; Robson, F. Intersectional challenges of conducting qualitative research in the Middle East. In Field Guide to Intercultural Research; Guttormsen, D., Lauring, J., Chapman, M., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2021; pp. 296–310. [Google Scholar]

- Gioia, D.A.; Corley, K.G.; Hamilton, A.L. Seeking Qualitative Rigor in Inductive Research: Notes on the Gioia Methodology. Organ. Res. Methods 2012, 16, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, N. Using templates in the thematic analysis of text. In Essential Guide to Qualitative Methods in Organizational Research; Cassell, C., Symon, G., Eds.; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2004; pp. 256–270. [Google Scholar]

- Ridgway, M.; Robson, F. Exploring the motivation and willingness of self-initiated expatriates, in the civil engineering industry, when considering employment opportunities in Qatar. Hum. Resour. Dev. Int. 2018, 21, 24–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, P.; Hopwood, N. A Practical Iterative Framework for Qualitative Data Analysis. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2009, 8, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tayah, M.-J.; Assaf, H. The Future of Domestic Work in the Countries of the Gulf Cooperation Council. Available online: www.abudhabidialogue.org (accessed on 21 May 2021).

- Ressia, S.; Strachan, G.; Bailey, J. Operationalizing Intersectionality: An Approach to Uncovering the Complexity of the Migrant Job Search in Australia. Gend. Work Organ. 2017, 24, 376–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Code | Nationality | Age | Children | Industry | Job Role/Seniority | Expatriate Status | Years in GCC | Career Coordination Strategy 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | British | 41–50 | 2 | Education | Professional | SIE | 4 | Egalitarian |

| P2 | British | 31–40 | 1 | Education | Administrative | SIE | 8 | Hierarchical |

| P3 | American | 41–50 | 1 | Aviation | Executive | SIE | 9 | Egalitarian |

| P4 | Romanian | 31–40 | 2 | Engineering | Senior Manager | AE | 4 | Hierarchical |

| P5 | British | 31–40 | 2 | Engineering | Management | SIE | 5 | Egalitarian |

| P6 | British | 31–40 | 0 | Aviation | Management | SIE | 6 | Hierarchical |

| P7 | American | 41–50 | 0 | Education | Management | SIE | 5 | Hierarchical |

| P8 | American | 41–50 | 1 | Healthcare | Department Head | SIE | 7 | Loose |

| P9 | British | 31–40 | 0 | Aviation | Management | SIE | 4 | Loose |

| Topic | Example Question Asked |

|---|---|

| Professional background | Please tell me about your professional background and any previous overseas experience. What were your reasons for relocating internationally? |

| Destination | What were your initial perceptions of [host country]? Where there any appealing/deterring factors? What were your aspirations for the international experience? |

| Adjustment | Can you tell me about your mobilisation experience? What initial cultural differences did you experience? What was the role of internal/external networks during your adjustment? What challenges did you face? What support did you receive? |

| Family | Who relocated with you? What opportunities did the international experience provide for your family? What challenges did your family face? How did you manage your work–life balance? |

| Career coordination strategy | How did you prioritise your career? How did you access career opportunities? Did you encounter any career barriers? Have you ever had to compromise on your career plan? How has your career plan changed? |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ridgway, M. Taking a Step Back? Expatriation Consequences on Women in Dual-Career Couples in the Gulf. Merits 2021, 1, 47-60. https://doi.org/10.3390/merits1010006

Ridgway M. Taking a Step Back? Expatriation Consequences on Women in Dual-Career Couples in the Gulf. Merits. 2021; 1(1):47-60. https://doi.org/10.3390/merits1010006

Chicago/Turabian StyleRidgway, Maranda. 2021. "Taking a Step Back? Expatriation Consequences on Women in Dual-Career Couples in the Gulf" Merits 1, no. 1: 47-60. https://doi.org/10.3390/merits1010006

APA StyleRidgway, M. (2021). Taking a Step Back? Expatriation Consequences on Women in Dual-Career Couples in the Gulf. Merits, 1(1), 47-60. https://doi.org/10.3390/merits1010006