Enhancing the Biopreservative Effect of Non-Starter Lactic Acid Bacteria Using Soluble Fiber During Cheese Ripening

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design

2.2. Materials

2.3. Spore Preparation

2.3.1. Aerobic Spores

2.3.2. Anaerobic Spores

2.4. Pilot-Scale Manufacturing of Cheddar Cheese with Added Soluble Fiber (Inulin)

2.5. Microbial Analysis

2.5.1. Total Plate Counts (TPC) and Spore Counts (SC) of Pasteurized Milk

2.5.2. Microbial Quality of Soluble Fiber (Inulin)

2.5.3. Sample Preparation of Cheese for Microbial Enumeration

2.5.4. Total Plate Counts of Cheese Samples with Added Inulin

2.5.5. Spore Counts of Cheese Samples with Added Inulin

2.5.6. Starter and Non-Starter Lactic Acid Bacteria (NSLAB) Counts of Cheese Samples with Added Inulin

2.5.7. Identification of NSLAB Isolates Using MALDI-TOF

2.6. Physicochemical Analysis

2.6.1. Moisture Content

2.6.2. Protein Content

2.6.3. Fat Content

2.6.4. pH

2.6.5. Free Fatty Acids

2.6.6. Visual Inspection of Cheese Samples for Bloating/Slits/Holes

2.7. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Microbial Analysis

3.1.1. Microbial Quality of Pasteurized Milk Used for Cheese Manufacturing

3.1.2. Microbial Quality of Soluble Fiber (Inulin)

3.1.3. Total Plate Counts (TPC) of Cheese Samples with Added Inulin

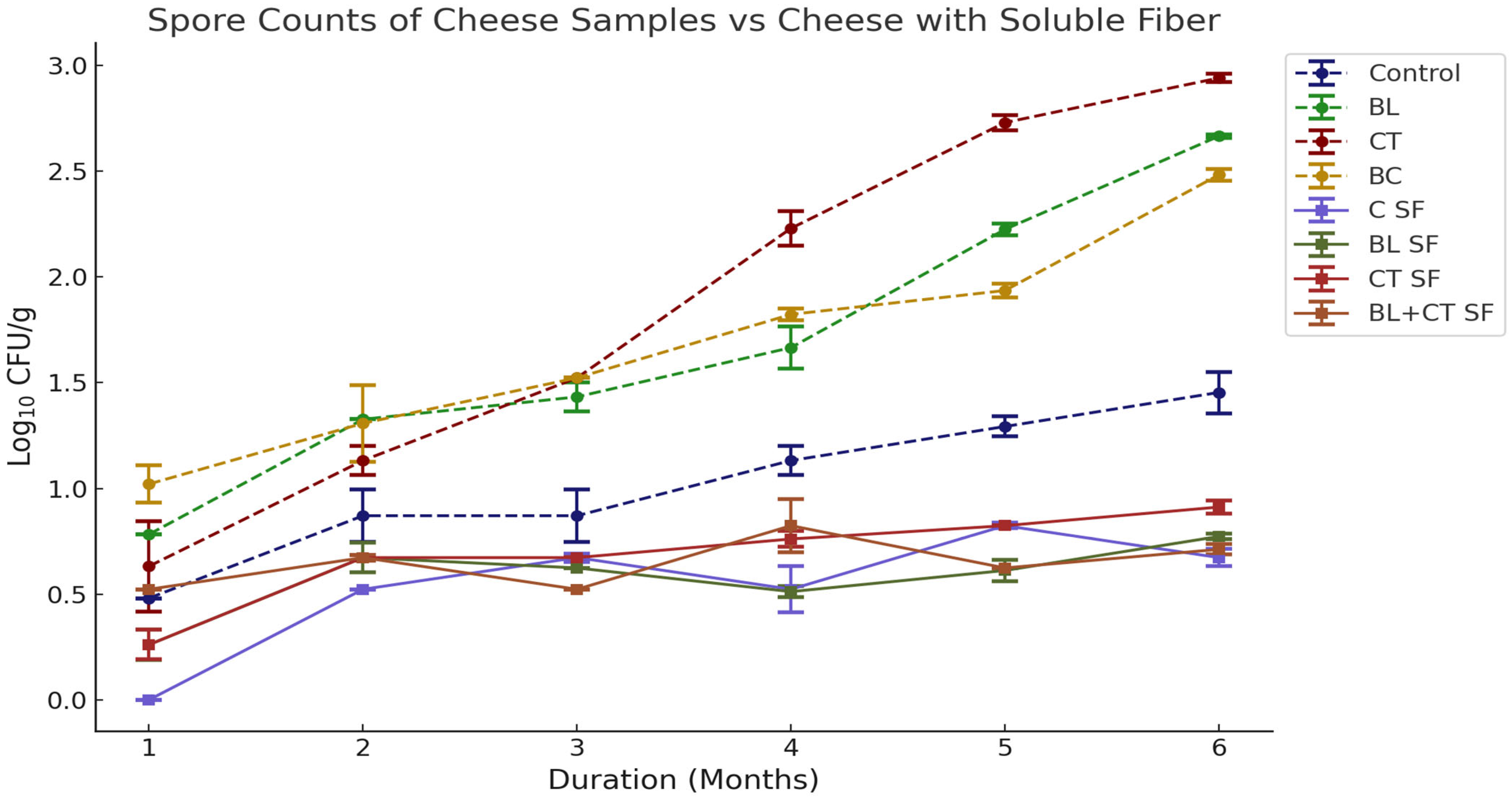

3.1.4. Changes in Spore Counts of Cheese Samples with Added Inulin

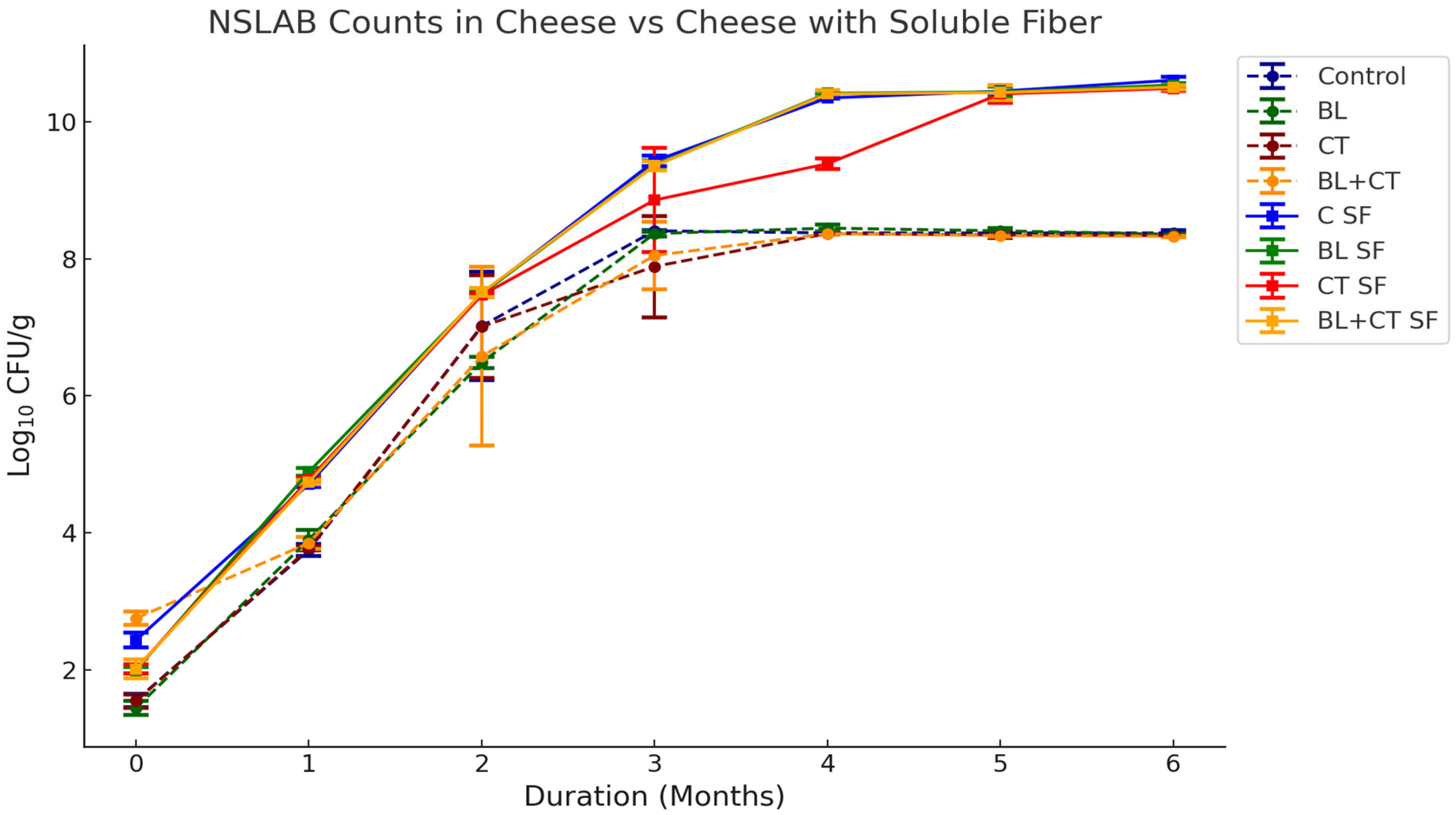

3.1.5. Starter and NSLAB Counts of Cheese Samples with Added Inulin

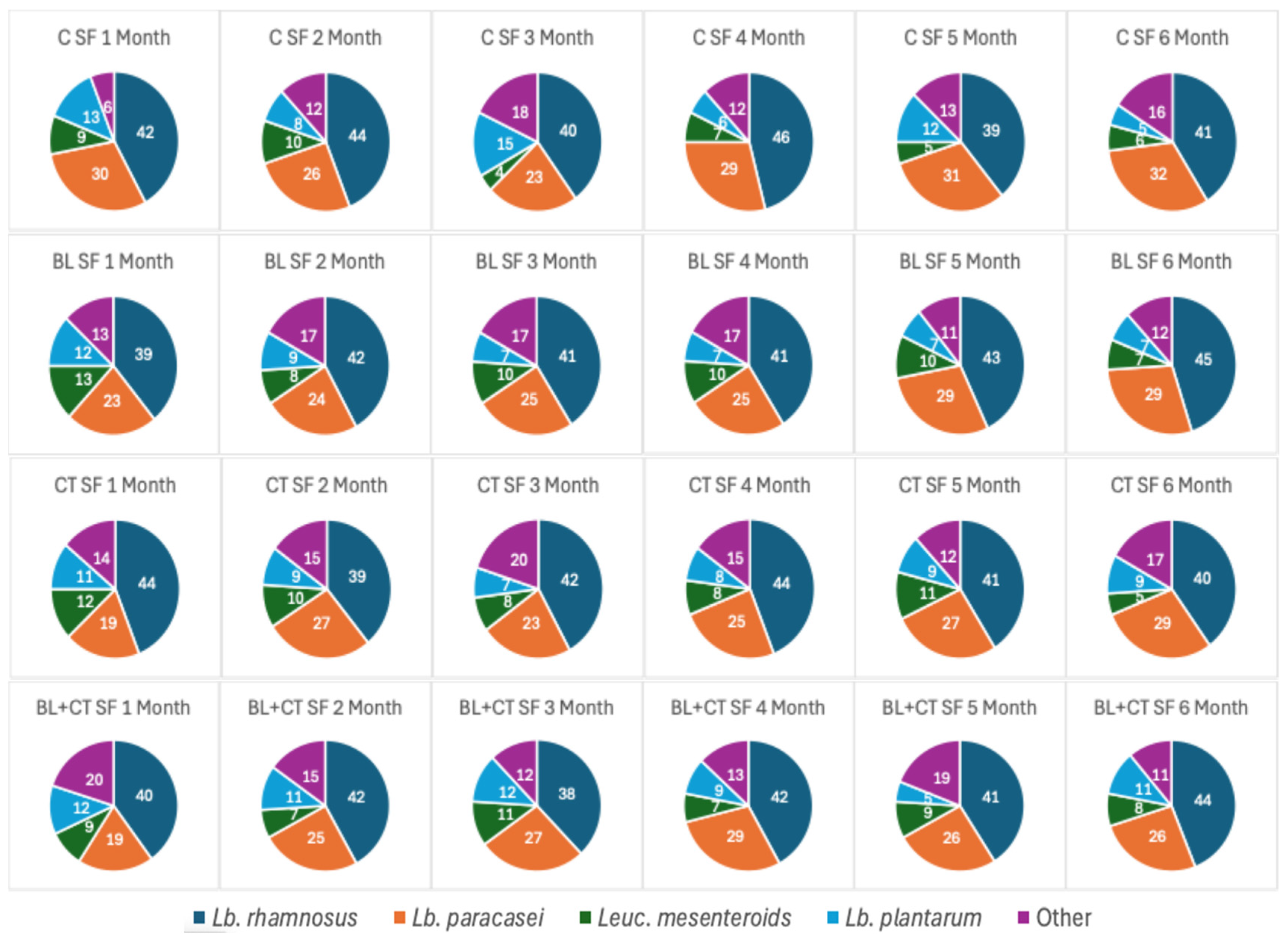

3.1.6. Percent Distribution of NSLAB by MALDI-TOF During Ripening

3.2. Physicochemical Analysis

3.2.1. Moisture Content During Cheese Ripening

3.2.2. Protein Content of Cheese Samples During Ripening

3.2.3. Fat Content During Cheese Ripening

3.2.4. Free Fatty Acids and pH During Cheese Ripening

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NSLAB | Nonstarter lactic acid bacteria |

| CFU | Colony forming unit |

| FFA | Free Fatty Acids |

| SF | Soluble Fiber |

References

- Murtaza, M.S.; Sameen, A.; Rehman, A.; Huma, N.; Hussain, F.; Hussain, S.; Cacciotti, I.; Korma, S.A.; Ibrahim, S.A.; Ma, Y.K. Physicochemical, techno-functional, and proteolytic effects of various hydrocolloids as fat replacers in low-fat cheddar cheese. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 8, 1440310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, A.; Parmar, A.; Panigrahi, S.P.; Verma, T.; Dhyano, P.; Bajya, S.L.; Singh, M.K. Exploring the probiotic and prebiotic dynamics of cheese: An updated review. Ann. Phytomed. 2024, 13, 360–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobbetti, M.; Di Cagno, R.; Calasso, M.; Neviani, E.; Fox, P.F.; De Angelis, M. Drivers that establish and assembly the lactic acid bacteria biota in cheeses. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 78, 244–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carminati, D.; Bonvini, B.; Francolino, S.; Ghiglietti, R.; Locci, F.; Tidona, F.; Mariut, M.; Abeni, F.; Zago, M.; Giraffa, G. Low-Level Clostridial Spores’ Milk to Limit the Onset of Late Blowing Defect in Lysozyme-Free, Grana-Type Cheese. Foods 2023, 12, 1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Brea, S.G.; Gómez-Torres, N.; Arribas, M.Á. Spore-forming bacteria in dairy products. In Microbiology in Dairy Processing: Challenges and Opportunities; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 11–36. [Google Scholar]

- Gopal, N.; Hill, C.; Ross, P.R.; Beresford, T.P.; Fenelon, M.A.; Cotter, P.D. The prevalence and control of Bacillus and related spore-forming bacteria in the dairy industry. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, C.J.; Gleeson, D.; Jordan, K.; Beresford, T.P.; Ross, R.P.; Fitzgerald, G.F.; Cotter, P.D. Anaerobic sporeformers and their significance with respect to milk and dairy products. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2015, 197, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Torres, N.; Ávila, M.; Gaya, P.; Garde, S. Prevention of late blowing defect by reuterin produced in cheese by a Lactobacillus reuteri adjunct. Food Microbiol. 2014, 42, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ávila, M.; Gómez-Torres, N.; Delgado, D.; Gaya, P.; Garde, S. Application of high pressure processing for controlling Clostridium tyrobutyricum and late blowing defect on semi-hard cheese. Food Microbiol. 2016, 60, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peruzy, M.F.; Blaiotta, G.; Aponte, M.; De Sena, M.; Murru, N. Late blowing defect in Grottone cheese: Detection of clostridia and control strategies. Ital. J. Food Saf. 2022, 11, 10162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosentino, C.; Paolino, R.; Freschi, P.; Calluso, A. Jenny milk as an inhibitor of late blowing in cheese: A preliminary report. J. Dairy Sci. 2013, 96, 3547–3550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbal, S.; Oner, Z. Optimisation of the inhibitory effect of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum, nisin, and lysozyme to prevent the late blowing defect in a cheese model. Czech J. Food Sci. 2024, 42, 330–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, M.C.; Carmo, M.R.; Balthazar, C.F.; Guimarães, J.T.; Esmerino, E.A.; Freitas, M.Q.; Silva, M.C.; Pimentel, T.C.; Cruz, A.G. Dairy products with prebiotics: An overview of the health benefits, technological and sensory properties. Int. Dairy J. 2021, 117, 105009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neri-Numa, I.A.; Arruda, H.S.; Geraldi, M.V.; Júnior, M.R.M.; Pastore, G.M. Natural prebiotic carbohydrates, carotenoids and flavonoids as ingredients in food systems. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2020, 33, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkett, A.M.; Francis, C.C.; Cho, S.; Finocchiaro, E. Short-Chain Fructooligosaccharide: A Low Molecular Weight Fructan; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Karimi, R.; Azizi, M.H.; Ghasemlou, M.; Vaziri, M. Application of inulin in cheese as prebiotic, fat replacer and texturizer: A review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015, 119, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Souza Oliveira, R.P.; Perego, P.; de Oliveira, M.N.; Converti, A. Effect of inulin on the growth and metabolism of a probiotic strain of Lactobacillus rhamnosus in co-culture with Streptococcus thermophilus. LWT 2012, 47, 358–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.; Alharbi, M.A.; Alharbi, N.K.; Rafiq, S.; Shahbaz, M.; Murtaza, S.; Raza, N.; Farooq, U.; Ali, M.; Imran, M. Effect of inulin on organic acids and microstructure of synbiotic cheddar-type cheese made from buffalo milk. Molecules 2022, 27, 5137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegab, O.W.; Abdel-Latif, E.F.; Zaki, H.M.; Moawad, A.A. Fundamental role of Lactobacillus plantarum and inulin in improving safety and quality of Karish cheese. Open Vet. J. 2021, 11, 356–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanal, S.N.; Anand, S.; Muthukumarappan, K. Evaluation of high-intensity ultrasonication for the inactivation of endospores of 3 bacillus species in nonfat milk. J. Dairy Sci. 2014, 97, 5952–5963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryser, E.T.; Kornacki, J.L. Standard Methods. In Standard Methods for the Examination of Dairy Products, 18th ed.; American Public Health Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Kornacki, J.L.; Ryser, E.T.; Mangione, C.M.; Wehr, H.M. Standard Methods for the Examination of Dairy Products, 18th ed.; American Public Health Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Torres, N.; Garde, S.; Peirotén, Á.; Ávila, M. Impact of Clostridium spp. on cheese characteristics: Microbiology, color, formation of volatile compounds and off-flavors. Food Control 2015, 56, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barzideh, Z.; Siddiqi, M.; Mohamed, H.M.; LaPointe, G. Dynamics of starter and non-starter lactic acid bacteria populations in long-ripened cheddar cheese using propidium monoazide (PMA) treatment. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC. Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC International; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- IDF Standard 20-A; Milk: Determination of Nitrogen Content (Kjeldahal Method). International Dairy Federation: Brussels, Belgium, 2001.

- AOAC. AOAC Official Method 989.05 Fat in Milk: Modified MojonnierEther Extraction Method. In Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC International; Latimer, G.W., Jr., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- British Standard BS 6776-5; Chemical Analysis of Cheese. Part 5. Determination of pH Value. BSI: London, UK, 1976; p. 770.

- Asif, M.; Nadeem, M.; Imran, M.; Ullah, R.; Tayyab, M.; Khan, F.A.; Al-Asmari, F.; Rahim, M.A.; Rocha, J.M.; Korma, S.A. Effect of fat contents of buttermilk on fatty acid composition, lipolysis, vitamins and sensory properties of cheddar-type cheese. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1209509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushik, R.; Anand, S. Studying the Population Dynamics of NSLAB and Their Influence on Spores During Cheese Ripening. Appl. Microbiol. 2025, 5, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatti, M.; Bottari, B.; Lazzi, C.; Neviani, E.; Mucchetti, G. Invited review: Microbial evolution in raw-milk, long-ripened cheeses produced using undefined natural whey starters. J. Dairy Sci. 2014, 97, 573–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montanuci, F.D.; Pimentel, T.C.; Garcia, S.; Prudencio, S.H. Effect of starter culture and inulin addition on microbial viability, texture, and chemical characteristics of whole or skim milk Kefir. Food Sci. Technol. 2012, 32, 580–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunová, S.; Kačániová, M.; Čuboň, J.; Haščík, P.; Lopašovský, Ľ. Evaluation of microbiological quality of selected cheeses during storage. Slovak J. Food Sci./Potravin. 2015, 9, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hanlon, M.; Choi, J.; Goddik, L.; Park, S.H. Microbial and chemical composition of Cheddar cheese supplemented with prebiotics from pasteurized milk to aging. J. Dairy Sci. 2022, 105, 2058–2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, P.F.; Guinee, T.P.; Cogan, T.M.; McSweeney, P.L.; Fox, P.F.; Guinee, T.P.; Cogan, T.M.; McSweeney, P.L. Microbiology of cheese ripening. In Fundamentals of Cheese Science; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2017; pp. 333–390. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, A.G.; Withers, S.E.; Banks, J.M. Energy sources of non-starter lactic acid bacteria isolated from Cheddar cheese. Int. Dairy J. 2000, 10, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gänzle, M.G.; Follador, R. Metabolism of oligosaccharides and starch in lactobacilli: A review. Front. Microbiol. 2012, 3, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, T.J.; Pieretti, G.G.; Marques, D.R.; da Silva Scapim, M.R.; Branco, I.G.; Madrona, G.S. Microbial, physical, chemical and sensory properties of Minas Frescal Cheese with Inulin and gum Acacia. Acta Scientiarum. Technol. 2015, 37, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzi, C.; Turroni, S.; Mancini, A.; Sgarbi, E.; Neviani, E.; Brigidi, P.; Gatti, M. Transcriptomic clues to understand the growth of Lactobacillus rhamnosus in cheese. BMC Microbiol. 2014, 14, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ávila, M.; Sánchez, C.; Calzada, J.; Mayer, M.J.; Berruga, M.I.; López-Díaz, T.M.; Narbad, A.; Garde, S. Isolation and characterization of new bacteriophages active against Clostridium tyrobutyricum and their role in preventing the late blowing defect of cheese. Food Res. Int. 2023, 163, 112222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardarelli, H.R.; Buriti, F.C.; Castro, I.A.; Saad, S.M. Inulin and oligofructose improve sensory quality and increase the probiotic viable count in potentially synbiotic petit-suisse cheese. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2008, 41, 1037–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Hao, X.; Wang, H.; Li, X.; Liu, L.; Yang, W.; Zhao, M.; Wang, L.; Bora, A.F.M. The effects of Lactobacillus plantarum combined with inulin on the physicochemical properties and sensory acceptance of low-fat Cheddar cheese during ripening. Int. Dairy J. 2021, 115, 104947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, P.F.; Guinee, T.P.; Cogan, T.M.; McSweeney, P.L. Fundamentals of Cheese Science; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sousa, M.; Ardö, Y.; McSweeney, P. Advances in the study of proteolysis during cheese ripening. Int. Dairy J. 2001, 11, 327–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, V.; McSweeney, P.; Magboul, A.; Fox, P. Proteolysis in cheese during ripening. Cheese: Chem. Phys. Microbiol. 2004, 1, 391–434. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, Y.F.; McSweeney, P.L.; Wilkinson, M.G. Lipolysis and free fatty acid catabolism in cheese: A review of current knowledge. Int. Dairy J. 2003, 13, 841–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falentin, H.; Postollec, F.; Parayre, S.; Henaff, N.; Le Bivic, P.; Richoux, R.; Thierry, A.; Sohier, D. Specific metabolic activity of ripening bacteria quantified by real-time reverse transcription PCR throughout Emmental cheese manufacture. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2010, 144, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Cano, I.; Rocha-Mendoza, D.; Ortega-Anaya, J.; Wang, K.; Kosmerl, E.; Jiménez-Flores, R. Lactic acid bacteria isolated from dairy products as potential producers of lipolytic, proteolytic and antibacterial proteins. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 103, 5243–5257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Settanni, L.; Moschetti, G. Non-starter lactic acid bacteria used to improve cheese quality and provide health benefits. Food Microbiol. 2010, 27, 691–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaya, J.; Barzideh, Z.; LaPointe, G. Symposium review: Interaction of starter cultures and nonstarter lactic acid bacteria in the cheese environment. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 3611–3629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Pasteurized Milk | TPC (Log10 CFU/mL) | Spore (Log10 CFU/mL) | pH |

|---|---|---|---|

| Batch 1 | 2.55 ± 0.07 | BDL | 6.58 ± 0.02 |

| Batch 2 | 2.55 ± 0.07 | BDL | 6.58 ± 0.02 |

| Batch 3 | 2.64 ± 0.06 | BDL | 6.56 ± 0.01 |

| Batch 4 | 2.64 ± 0.06 | BDL | 6.56 ± 0.01 |

| Parameters | |

|---|---|

| TPC (Log10 CFU/g) | 0.99 ± 0.10 |

| Coliforms (Log10 CFU/g) | ≤1.0 log |

| Spores (Log10 CFU/g) | BDL |

| Duration | Treatments | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Months) | T1 (C SF) | T2 (BL SF) | T3 (CT SF) | T4 (BL+CT SF) |

| 0 | 8.57 ± 0.02 cC | 8.73 ± 0.05 bC | 8.79 ± 0.03 bC | 8.90 ± 0.04 aC |

| 1 | 9.42 ± 0.01 aB | 9.46 ± 0.03 aB | 9.42 ± 0.03 aB | 9.43 ± 0.02 aB |

| 2 | 9.45 ± 0.03 aB | 9.51 ± 0.09 aB | 9.48 ± 0.07 aB | 9.45 ± 0.01 aB |

| 3 | 9.41 ± 0.01 aB | 9.37 ± 0.01 aB | 9.37 ± 0.04 aB | 9.38 ± 0.04 aB |

| 4 | 12.41 ± 0.03 aA | 12.42 ± 0.03 aA | 12.44 ± 0.02 aA | 12.41 ± 0.03 aA |

| 5 | 12.41 ± 0.05 aA | 12.44 ± 0.01 aA | 12.43 ± 0.01 aA | 12.40 ± 0.01 aA |

| 6 | 12.40 ± 0.02 aA | 12.39 ± 0.03 aA | 12.38 ± 0.03 aA | 12.37 ± 0.01 aA |

| Duration | Treatments | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Months) | T1 (C SF) | T2 (BL SF) | T3 (CT SF) | T4 (BL+CT SF) |

| 0 | 8.03 ± 0.12 aA | 8.12 ± 0.18 aA | 8.01 ± 0.06 aA | 8.14 ± 0.23 aA |

| 1 | 7.36 ± 0.0 aB | 6.40 ± 0.02 bB | 6.36 ± 0.03 bB | 6.37 ± 0.01 bB |

| 2 | 3.94 ± 0.01 aC | 3.74 ± 0.17 aC | 3.34 ± 0.05 bC | 3.42 ± 0.06 bC |

| 3 | 2.73 ± 0.13 bD | 2.64 ± 0.10 bD | 2.62 ± 0.01 bD | 3.05 ± 0.42 aD |

| 4 | 0.92 ± 0.06 aE | 0.88 ± 0.12 aE | 0.91 ± 0.09 aE | 0.90 ± 0.14 aE |

| 5 | 0.42 ± 0.04 aF | 0.40 ± 0.08 aF | 0.42 ± 0.17 aF | 0.40 ± 0.23 aF |

| 6 | 0.10 ± 0.43 bF | 0.15 ± 0.15 bF | 0.20 ± 0.23 aF | 0.22 ± 0.19 aF |

| Duration | Treatments | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Months) | T1 (C SF) | T2 (BL SF) | T3 (CT SF) | T4 (BL+CT SF) |

| 1 | 38.08 ± 0.58 cA | 38.96 ± 0.10 bA | 39.15 ± 0.67 bA | 39.73 ± 1.76 aA |

| 2 | 39.37 ± 0.44 aA | 38.52 ± 0.19 bA | 37.63 ± 1.73 cB | 38.99 ± 0.85 bB |

| 3 | 38.01 ± 0.44 aB | 36.94 ± 0.79 cB | 37.83 ± 1.36 bB | 37.77 ± 1.55 bC |

| 4 | 36.31 ± 0.29 bC | 36.73 ± 0.80 bB | 36.48 ± 1.31 bC | 37.04 ± 1.22 aD |

| 5 | 36.93 ± 0.89 bD | 36.38 ± 0.45 bC | 37.62 ± 1.02 aB | 36.93 ± 0.93 bD |

| 6 | 36.13 ± 0.99 cE | 35.88 ± 1.30 bD | 36.63 ± 0.60 aC | 36.91 ± 0.09 aD |

| Duration | Cheese Categories | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Months) | T1 (C SF) | T2 (BL SF) | T3 (CT SF) | T4 (BL+CT SF) |

| 1 | 24.56 ± 0.20 | 24.07 ± 0.51 | 24.73 ± 0.49 | 23.78 ± 0.19 |

| 2 | 24.59 ± 0.13 | 24.11 ± 0.25 | 24.52 ± 0.12 | 23.62 ± 0.28 |

| 3 | 24.38 ± 0.17 | 24.05 ± 0.16 | 24.62 ± 0.02 | 23.63 ± 0.30 |

| 4 | 24.99 ± 0.23 | 24.81 ± 0.13 | 24.39 ± 0.26 | 24.25 ± 0.93 |

| 5 | 24.97 ± 0.65 | 24.91 ± 0.24 | 24.77 ± 0.16 | 24.14 ± 0.16 |

| 6 | 25.20 ± 0.58 | 25.01 ± 0.22 | 25.36 ± 0.54 | 24.65 ± 0.34 |

| Duration | Treatments | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Months) | T1 (C SF) | T2 (BL SF) | T3 (CT SF) | T4 (BL+CT SF) |

| 1 | 33.92 ± 0.17 | 34.18 ± 0.95 | 34.12 ± 0.92 | 35.27 ± 0.49 |

| 2 | 34.11 ± 1.03 | 33.91 ± 0.54 | 33.28 ± 0.14 | 34.13 ± 0.24 |

| 3 | 34.53 ± 0.02 | 34.50 ± 0.33 | 34.70 ± 0.78 | 34.02 ± 0.52 |

| 4 | 34.88 ± 0.28 | 35.03 ± 0.58 | 33.32 ± 0.36 | 34.56 ± 0.03 |

| 5 | 33.62 ± 0.93 | 34.29 ± 0.95 | 34.55 ± 0.63 | 34.95 ± 0.70 |

| 6 | 34.19 ± 0.53 | 33.68 ± 0.19 | 35.19 ± 0.58 | 34.92 ± 0.45 |

| Duration | Treatments | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Months) | T1 (C SF) | T2 (BL SF) | T3 (CT SF) | T4 (BL+CT SF) |

| 1 | 0.68 ± 0.04 C | 0.63 ± 0.01 C | 0.60 ± 0.06 D | 0.69 ± 0.01 D |

| 2 | 0.73 ± 0.03 C | 0.73 ± 0.04 C | 0.76 ± 0.04 C | 0.71 ± 0.05 D |

| 3 | 0.79 ± 0.02 C | 0.80 ± 0.04 B | 0.78 ± 0.01 C | 0.80 ± 0.00 C |

| 4 | 0.84 ± 0.06 B | 0.82 ± 0.02 B | 0.82 ± 0.07 B | 0.84 ± 0.01 B |

| 5 | 0.89 ± 0.01 B | 0.87 ± 0.05 B | 0.88 ± 0.01 B | 0.87 ± 0.02 B |

| 6 | 0.98 ± 0.06 A | 0.99 ± 0.03 A | 0.96 ± 0.05 A | 0.96 ± 0.02 A |

| Duration | Cheese Categories | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Months) | T1 (C SF) | T2 (BL SF) | T3 (CT SF) | T4 (BL+CT SF) |

| 1 | 5.00 ± 0.04 | 4.96 ± 0.00 | 4.99 ± 0.01 | 4.98 ± 0.04 |

| 2 | 4.98 ± 0.02 | 4.97 ± 0.00 | 4.96 ± 0.02 | 5.04 ± 0.06 |

| 3 | 5.00 ± 0.01 | 5.02 ± 0.07 | 4.98 ± 0.03 | 4.98 ± 0.07 |

| 4 | 4.99 ± 0.01 | 5.02 ± 0.02 | 4.99 ± 0.01 | 4.99 ± 0.04 |

| 5 | 4.95 ± 0.02 | 4.98 ± 0.06 | 5.03 ± 0.03 | 5.00 ± 0.01 |

| 6 | 5.01 ± 0.03 | 4.97 ± 0.04 | 5.03 ± 0.03 | 4.97 ± 0.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kaushik, R.; Anand, S. Enhancing the Biopreservative Effect of Non-Starter Lactic Acid Bacteria Using Soluble Fiber During Cheese Ripening. Appl. Microbiol. 2025, 5, 132. https://doi.org/10.3390/applmicrobiol5040132

Kaushik R, Anand S. Enhancing the Biopreservative Effect of Non-Starter Lactic Acid Bacteria Using Soluble Fiber During Cheese Ripening. Applied Microbiology. 2025; 5(4):132. https://doi.org/10.3390/applmicrobiol5040132

Chicago/Turabian StyleKaushik, Rakesh, and Sanjeev Anand. 2025. "Enhancing the Biopreservative Effect of Non-Starter Lactic Acid Bacteria Using Soluble Fiber During Cheese Ripening" Applied Microbiology 5, no. 4: 132. https://doi.org/10.3390/applmicrobiol5040132

APA StyleKaushik, R., & Anand, S. (2025). Enhancing the Biopreservative Effect of Non-Starter Lactic Acid Bacteria Using Soluble Fiber During Cheese Ripening. Applied Microbiology, 5(4), 132. https://doi.org/10.3390/applmicrobiol5040132