Composition and Occurrence of Airborne Fungi in Two Urbanized Areas of the City of Sofia, Bulgaria

Abstract

1. Introduction

Status of the Problem in Sofia

- To assess the weekly dynamics of fungal spore distribution at the two sampling sites;

- To determine the taxonomic affiliation of the isolated fungi and identify the dominant fungal genera and strains;

- To test the sensitivity of the isolates to commercially available antifungal agents.

2. Materials and Methods

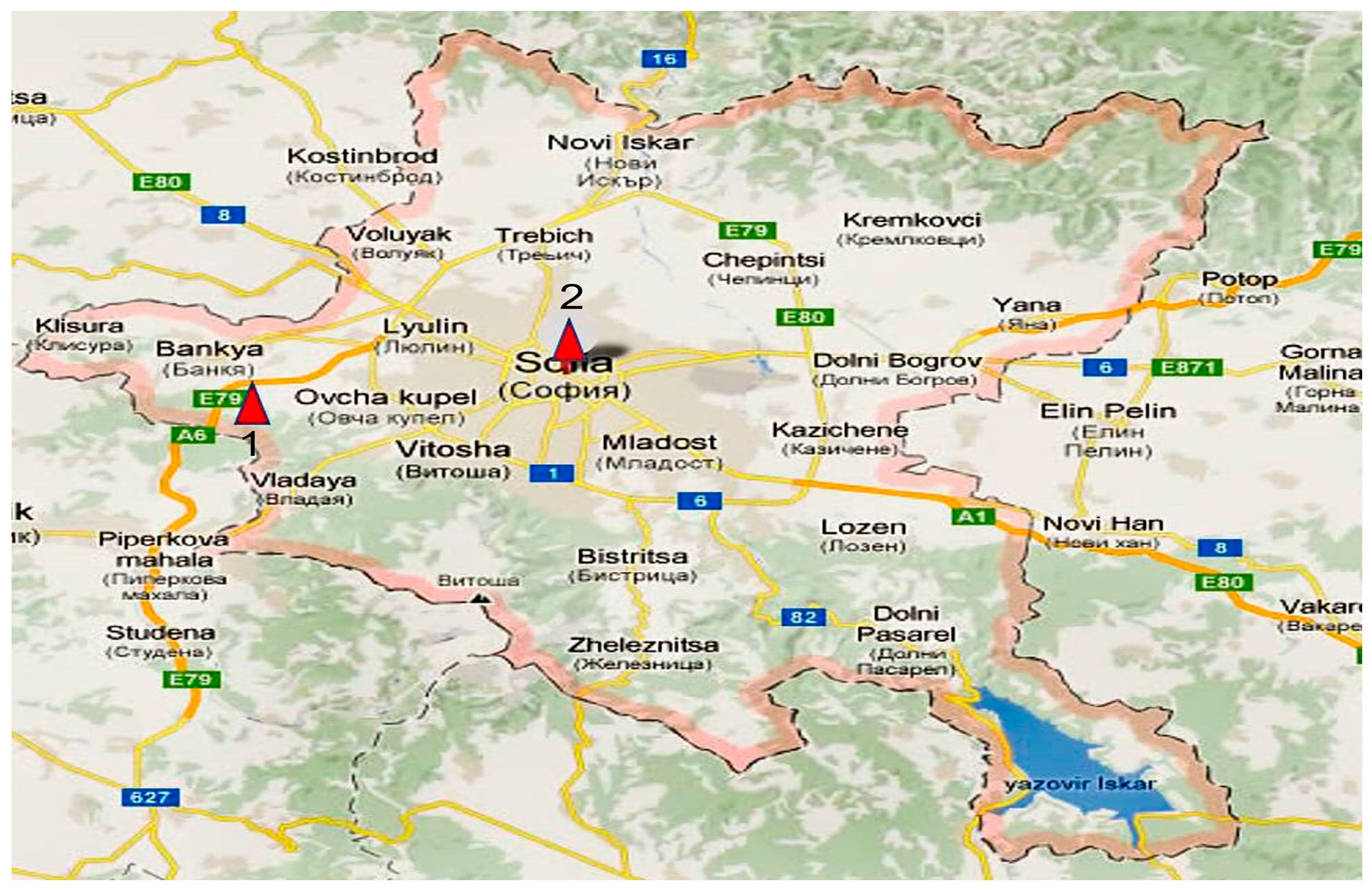

2.1. Research Focus and Sampling Locations

2.2. Sampling Methods

2.2.1. Koch Sedimentation Method

2.2.2. Andersen Cascade Impactor

2.3. Culture Media and Incubation Conditions

- Yeast Extract Glucose Chloramphenicol Agar (YGC): Yeast extract 5.0, D (+)-Glucose 20.0, Chloramphenicol 0.1, Agar 14.9, final pH 6.6 ± 0.2 at 25 °C;

- Gause Medium (G1): Soluble starch 20.0 g, KNO3 1.0 g, NaCl 0.5 g, MgSO4 × 7H2O 0.5 g, K2HPO4 0.5 g, FeSO4 × 7H2O 10.0 mg, Agar 15.0 g, distilled water 1.0 L, Adjusted pH 7.4.

2.4. Isolation of Pure Cultures

2.5. Identification of Fungal Isolates

2.5.1. Classical Identification Methods

2.5.2. Molecular Genetic Identification

2.6. Estimation of Airborne Fungal Diversity

2.7. Sensitivity of Dominant Fungal Species to Antifungal Agents

2.8. Determination of the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration of the Two Tested Antifungal Preparations, Nystatin and Amphotericin, Against the Identified Fungal Species

2.9. Statistical Evaluation

3. Results

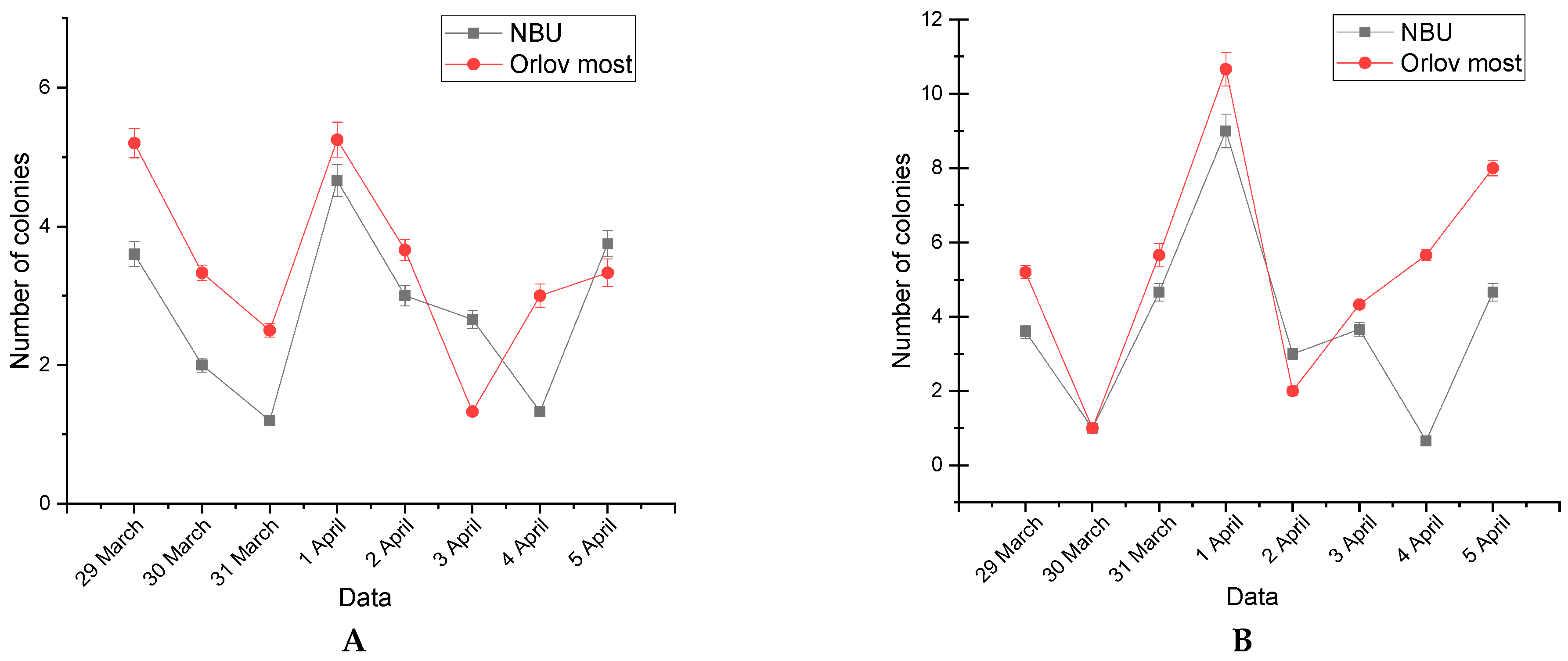

3.1. Quantitative Analysis

3.2. Weekly Dynamics of Airborne Fungal Spores

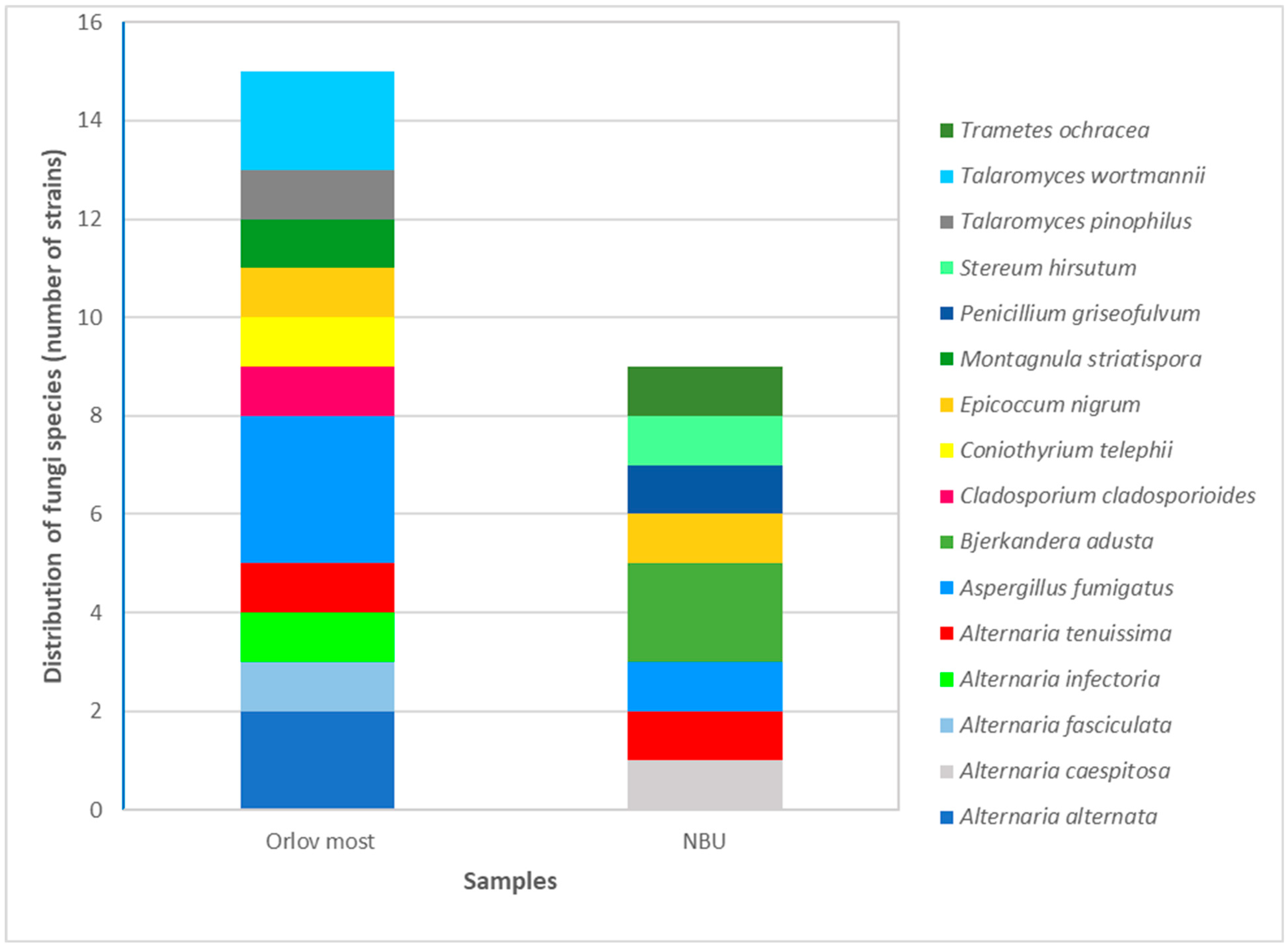

3.3. Identification of Fungal Isolates

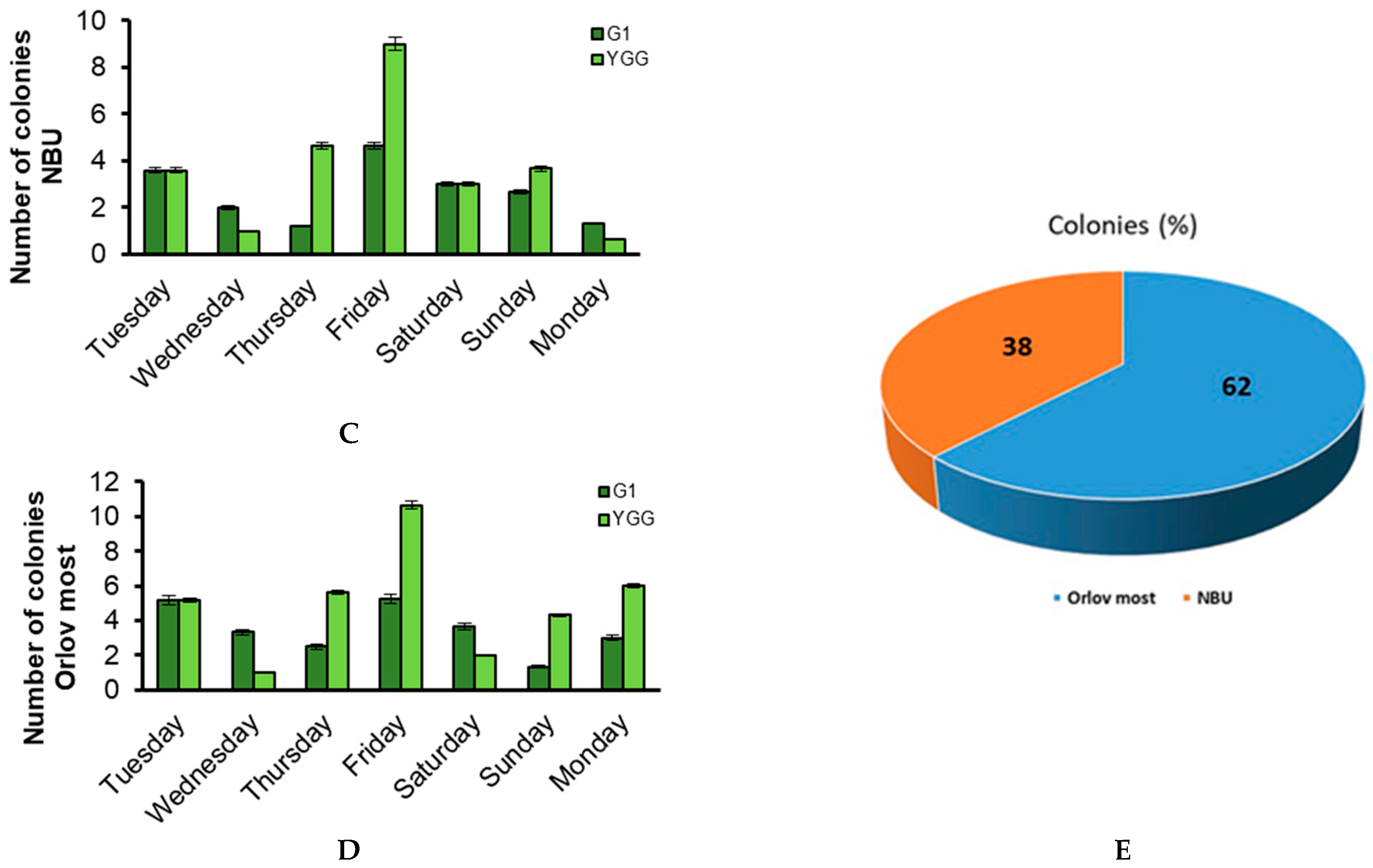

3.3.1. Classical Taxonomic Identification

3.3.2. Molecular Genetic Identification

3.4. Sensitivity of Isolated Fungal Strains to the Antifungal Agents Nystatin and Amphotericin

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kelishadi, R.; Poursafa, P. Air pollution and non-respiratory health hazards for children. Arch. Med. Sci. 2010, 6, 483–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietras, B.G. The origin of dust particles in atmospheric air in Krakow (Poland) (atmospheric background). Land 2022, 11, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzyzanowski, M.; Apte, J.S.; Bonjour, S.P.; Brauer, M.; Cohen, A.J.; Prüss-Ustun, A.M. Air pollution in the mega-cities. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2014, 1, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- States of Global Air. Air Pollution and Health in Cities. 2022. Available online: https://www.stateofglobalair.org/resources/health-in-cities (accessed on 22 September 2022).

- Marlier, M.E.; Jina, A.S.; Kinney, P.L.; DeFries, R.S. Extreme air pollution in global megacities. Curr. Clim. Change Rep. 2016, 2, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health Effects Institute. Air Quality and Health in Cities: A State of Global Air Report 2022; Health Effects Institute: Boston, MA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- US EPA (US Environmental Protection Agency). Particulate Matter (PM) Basics. 2018. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/pm-pollution/particulate-matter-pm-basics (accessed on 22 September 2018).

- Ghosh, B.; Lal, H.; Srivastava, A. Review of bioaerosols in indoor environment with special reference to sampling, analysis and control mechanisms. Environ. Int. 2015, 85, 254–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franchitti, E.; Caredda, C.; Anedda, E.; Traversi, D. Urban aerobiome and effects on human health: A systematic review and missing evidence. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szylak-Szydlowski, M.; Kulig, A.; Miaśkiewicz-Peska, E. Seasonal changes in the concentrations of airborne bacteria emitted from a large wastewater treatment plant. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2016, 115, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emetere, M.E.; Oloke, O.C.; Afolalu, S.A.; Joshua, O. Short review on the atmospheric bioaerosols. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 665, 012054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillai, S.D.; Ricke, S.C. Bioaerosols from municipal and animal wastes: Background and contemporary issues. Can. J. Microbiol. 2002, 48, 681–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasanen, P.; Pasanen, A.L.; Janunen, M. Water condensation promotes fungal growth in ventilation ducts. Indoor Air 2000, 3, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.M.; Harrison, R.M. The effects of meteorological factors on atmospheric bioaerosol concentrations—A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2004, 326, 151–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, Z.G.; Ouyang, Z.Y.; Zheng, H.; Wang, X.K.; Hu, L.F. Culturable airborne bacteria in outdoor environments in Beijing, China. Microb. Ecol. 2007, 54, 487–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, B.L.; Cookson, J.T. Natural atmospheric microbial conditions in a typical suburban area. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1983, 45, 919–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, W.; Li, Y.; Bai, W.; Hou, J.; Ma, T.; Zeng, X.; Zhang, L.; An, T. The source and transport of bioaerosols in the air: A review. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 2021, 15, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veresoglou, S.D.; Rillig, M.C. Challenging cherished ideas in mycorrhizal ecology: The Baylis postulate. New Phytol. 2014, 204, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez, A.; Amo De Paz, G.; Rastrojo, A.; Ferencova, Z.; Gutiérrez-Bustillo, A.M.; Alcamí, A.; Moreno, D.A.; Guantes, R. Temporal patterns of variability for prokaryotic and eukaryotic diversity in the urban air of Madrid (Spain). Atmos. Environ. 2019, 217, 116972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.Z.; Li, Y.P.; Xie, W.W.; Lu, R.; Mu, F.F.; Bai, W.Y.; Du, S.L. Temporal-spatial variations of fungal composition in PM2.5 and source tracking of airborne fungi in mountainous and urban regions. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 708, 135027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S.H.; Cho, J.H. Evaluation of airborne fungi and the effects of a platform screen door and station depth in 25 underground subway stations in Seoul, South Korea. Air Qual. Atmos. Health 2016, 9, 561–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Hu, Z.; Zhou, M.; Hu, J.; Yao, X.; Zhang, H.; Li, Z.; Lou, L.; Xi, C.; Qian, H.; et al. The distribution variance of airborne microorganisms in urban and rural environments. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 247, 898–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalakrishnan, S.; Arigela, R.; Gupta, S.K.; Raghunathan, R. Dynamic response of passive release of fungal spores from exposure to air. J. Aerosol Sci. 2019, 133, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagerman, A.D.; South, D.D.; Sondgerath, T.C.; Patyk, K.A.; Sanson, R.L.; Schumacher, R.S.; Delgado, A.H.; Magzamen, S. Temporal and geographic distribution of weather conditions favorable to airborne spread of foot-and-mouth disease in the coterminous United States. Prev. Vet. Med. 2018, 161, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bui, V.N.; Nguyen, T.T.; Hung, N.V.; Bui, A.N.; McCallion, K.A.; Lee, H.S.; Than, S.T.; Coleman, K.K.; Gray, G.C. Bioaerosol sampling to detect avian influenza virus in Hanoi’s largest live poultry market. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2019, 68, 972–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.; Fan, C.; Qi, J.; Li, H.; Dong, L.; Hu, W.; Kojima, T.; Zhang, D. Decrease of bioaerosols in westerlies from Chinese coast to the northwestern Pacific: Case data comparisons. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 864, 161040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, P.; Shen, D.; Tang, Q.; Huang, K.; Li, C. PM2.5 from a broiler breeding production system: The characteristics and microbial community analysis. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 256, 113368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, G.; Han, Y.; Li, L.; Liu, J. Characterization and source analysis of indoor/outdoor culturable airborne bacteria in a municipal wastewater treatment plant. J. Environ. Sci. China 2018, 74, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Górny, R.L. Microbial aerosols: Sources, properties, health effects, exposure assessment—A review. KONA Powder Part. J. 2020, 37, 64–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, A.; Grimberg, S.J.; Holsen, T.M. A static water surface sampler to measure bioaerosol deposition and characterize microbial community diversity. J. Aerosol Sci. 2005, 36, 639–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Després, V.; Huffman, J.A.; Burrows, S.M.; Hoose, C.; Safatov, A.; Buryak, G.; Fröhlich-Nowoisky, J.; Elbert, W.; Andreae, M.O.; Pöschl, U.; et al. Primary biological aerosol particles in the atmosphere: A review. Tellus B Chem. Phys. Meteorol. 2012, 64, 15598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Li, F.; Yang, J.; Liu, X.; Cho, W.C. MicroRNAs as regulators of airborne pollution-induced lung inflammation and carcinogenesis. Arch. Toxicol. 2015, 89, 677–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelova, B.; Iliev, M. Metagenomic analysis of microbial diversity in the urban air of Sofia (Bulgaria) during spring and winter. Proc. Bulg. Acad. Sci. 2024, 77, 1449–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Goel, A.K. Prevalence of methicillin resistant Staphylococcal bioaerosols in and around residential houses in an urban area in Central India. J. Pathog. 2016, 2016, 7163615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, X.; Kong, S.; Zheng, S.; Cheng, Y.; Wu, F.; Niu, Z.; Yan, Q.; Wu, J.; Zheng, H.; Zheng, M.; et al. Variation of airborne DNA mass ratio and fungal diversity in fine particles with day–night difference during an entire winter haze evolution process of Central China. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 694, 133802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatahinia, M.; Zarei-Mahmoudabadi, A.; Shokri, H.; Ghaymi, H. Monitoring of Mycoflora in outdoor air of different localities of Ahvaz, Iran. J. Mycol. Med. 2018, 28, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.W.; Kendrick, B. A year-round study on functional relationships of airborne fungi with meteorological factors. Int. J. Biometeorol. 1995, 39, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Celenk, S.; Bicakci, A.; Erkan, P.; Aybeke, M. Cladosporium Link ex Fr. and Alternaria Nees ex Fr. spores in the atmosphere of Edirne. J. Biol. Environ. Sci. 2007, 1, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Grinn-Gofron, A. Cladosporium spores in the air of Szczecin. Acta Agrobot. 2007, 60, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ianovici, N.; Tudorica, D. Aeromycoflora in outdoor environment of Timisoara City (Romania). Not. Sci. Biol. 2009, 1, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrissey, C.O. Diagnosis and management of invasive fungal infections due to non-Aspergillus moulds. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2025, 80 (Suppl. S1), i17–i39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonc, E.; Plewa, K. Comparison of indoor and outdoor bioaerosols in poultry farming. In Advanced Topics in Environmental Health and Air Pollution Case Studies; InTech: Rijeka, Croatia, 2011; pp. 339–351. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, J.H.; Lee, J.E.; Lee, C.H.; Kim, S.S.; Lee, B.U. Treatment of fungal bioaerosols by a high-temperature, short-time process in a continuous-flow system. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 2742–2749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliev, M.; Ilieva, R.; Nedkov, I.; Pelkin, A.; Terziyska, V. Seasonal variability of ambient bioaerosol concentrations over densely populated central area in Sofia, Bulgaria: Focus on spring and summer. Proc. Bulg. Acad. Sci. 2025, 78, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.Y.; Fong, J.J.; Park, M.S.; Chang, L.; Lim, Y.W. Identifying airborne fungi in Seoul, Korea using metagenomics. J. Microbiol. 2014, 52, 465–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón-Ezquerro, M.C.; Serrano-Silva, N.; Brunner-Mendoza, C. Metagenomic characterisation of bioaerosols during the dry season in Mexico City. Aerobiologia 2020, 36, 493–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Fu, H.; Wang, W.; Liu, J.; Meng, Q.; Wang, W. Characteristics of bacterial and fungal aerosols during the autumn haze days in Xi’an, China. Atmos. Environ. 2015, 122, 439–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wessels, J.G.H. Fungal hydrophobins: Proteins that function at an interface. Trends Plant Sci. 1996, 1, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon-Nobbe, B.; Denk, U.; Poll, V.; Rid, R.; Breitenbach, M. The spectrum of fungal allergy. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2008, 145, 58–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Bracero, M.; Markey, E.; Clancy, J.H.; McGillicuddy, E.J.; Sewell, G.; O’Connor, D.J. Airborne fungal spore review, new advances and automatisation. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abel-Fernández, E.; Martínez, M.J.; Galán, T.; Pineda, F. Going over fungal allergy: Alternaria alternata and its allergens. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandit, T.; Singh, S.; Singh, A.B. Prevalence of culturable and nonculturable airborne fungi in a grain store in Delhi. Aerobiologia 1995, 11, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gams, W.; Anderson, T.-H. Compendium of Soil Fungi; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- White, T.J.; Bruns, T.; Lee, S.; Taylor, J. Amplification and Direct Sequencing of Fungal Ribosomal RNA Genes for Phylogenetics. In PCR Protocols; Innis, M.A., Gelfand, D.H., Sninsky, J.J., White, T.J., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1990; pp. 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoch, C.L.; Seifert, K.A.; Huhndorf, S.; Robert, V.; Spouge, J.L.; Levesque, C.A.; Chen, W.; Fungal Barcoding Consortium. Nuclear Ribosomal Internal Transcribed Spacer (ITS) Region as a Universal DNA Barcode Marker for Fungi. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 6241–6246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magurran, A.E. Measuring Biological Diversity; Blackwell Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Krebs, C.J. Ecological Methodology, 2nd ed.; Benjamin/Cummings: Menlo Park, CA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Adhikari, A.; Sen, M.M.; Gupta-Bhattacharya, S.; Chanda, S. Airborne viable, non-viable, and allergenic fungi in a rural agricultural area of India: A 2-year study at five outdoor sampling stations. Sci. Total Environ. 2004, 326, 123–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolov, G.; Kandova, Y.; Hristova, R.; Nedyalkov, M.; Petrunov, B. The role of fungal allergens in respiratory diseases in Bulgaria. In Allergy, Asthma & Immunology: From Basic Science to Clinical Application, Proceedings of the V World Asthma and COPD Forum, New York, NY, USA, 21–24 April 2012; WIPO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012; pp. 47–54. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Georgi-Nikolov-7/publication/236031853_The_role_of_fungal_allergensin_respiratory_diseases_in_Bulgaria/links/55d4108a08ae7fb244f59250/The-role-of-fungal-allergensin-respiratory-diseases-in-Bulgaria.pdf (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- Jaeger, E.E.; Carroll, N.M.; Choudhury, S.; Dunlop, A.A.; Towler, H.M.; Matheson, M.M.; Adamson, P.; Okhravi, N.; Lightman, S. Rapid detection and identification of Candida, Aspergillus, and Fusarium species in ocular samples using nested PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2000, 38, 2902–2908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, D.; Ilieva, M.; Fritz, T.; Galler, H.; Habib, J.; Kriso, A.; Kropsch, M.; Ofner-Kopeinig, P.; Reinthaler, F.F.; Strasser, A.; et al. Background concentrations of airborne, culturable fungi and dust particles in urban, rural and mountain regions. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 892, 164700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigorova-Pesheva, B.; Kadinov, G. Airborne microorganisms in hot point and green areas at different height of ground air. Int. Multidiscip. Sci. GeoConf. SGEM 2024, 24, 367–374. [Google Scholar]

- Hai, V.D.; Hoang, S.M.T.; Hung, N.T.Q.; Ky, N.M.; Gwi-Nam, B.; Ki-hong, P.; Chang, S.W.; Bach, Q.V.; Nhu-Trang, T.T.; Nguyen, D.D. Characteristics of airborne bacteria and fungi in the atmosphere in Ho Chi Minh city, Vietnam—A case study over three years. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2019, 145, 104819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvetnić, Z.; Pepeljnjak, S. Distribution and mycotoxin-producing ability of some fungal isolates from the air. Atmos. Environ. 1997, 31, 491–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.D. Fungi as contaminants in indoor air. Atmos. Environ. Part A 1992, 26, 2163–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Subai, A.A. Air-borne fungi at Doha, Qatar. Aerobiologia 2002, 18, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorenson, W.G. Fungal spores: Hazardous to health? Environ. Health Perspect. 1999, 107, 469–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurup, V.P.; Shen, H.-D.; Banerjee, B. Respiratory fungal allergy. Microbes Infect. 2000, 2, 1101–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, R.K.; Portnoy, J.M. The role and abatement of fungal allergens in allergic diseases. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2001, 107, S430–S440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vagelas, I.; Gougoulias, N.; Nedesca, E.-D.; Liviu, G. Bread contamination with fungus. Carpathian J. Food Sci. Technol. 2011, 3, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Hargreaves, M.; Parappukkaran, S.; Morawska, L.; Hitchins, J.; He, C.; Gilbert, D. A pilot investigation into association between indoor airborne fungal and non-biological particle concentrations in residential houses in Brisbane, Australia. Sci. Total Environ. 2003, 312, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nageen, Y.; Wang, X.; Pecoraro, L. Seasonal variation of airborne fungal diversity and community structure in urban outdoor environments in Tianjin, China. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1043224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelova, B.; Ilieva, R.; Iliev, M.; Nedkov, I.; Stoyanov, D.; Groudeva, V. Investigation of microbiota in atmospheric aerosols during lidar monitoring of highly urbanized area in Sofia city. Sci. Sess. Fac. Biol. 2020, 105, 24–31. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, A.; Ganguli, M.; Singh, A.B. Fungal spores are an important component of library air. Aerobiologia 1995, 11, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosas, I.; Calderón, C.; Martínez, L.; Ulloa, M.; Lacey, J. Indoor and outdoor airborne fungal propagule concentrations in Mexico City. Aerobiologia 1997, 13, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waisel, Y.; Ganor, E.; Glikman, M.; Epstein, V.; Brenner, S. Airborne fungal spores in the coastal plain of Israel: A preliminary survey. Aerobiologia 1997, 13, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picco, A.M.; Rodolfi, M. Airborne fungi as biocontaminants at two Milan underground stations. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2000, 45, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.Y.; Lee, C.C.; Li, F.C.; Ma, Y.P.; Su, H.J. The seasonal distribution of bioaerosols in municipal landfill sites: A 3-yr study. Atmos. Environ. 2002, 36, 4385–4395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelton, B.; Kirkland, K.H.; Flanders, W.D.; Morris, G.K. Profiles of airborne fungi in buildings and outdoor environments in the United States. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002, 68, 1743–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuder, E.M. Seasonal variations in the occurrence of culturable airborne fungi in outdoor and indoor air in Cracow. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2003, 52, 203–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colakoglu, G. Airborne fungal spores at the Belgrad forest near the city of Istanbul (Turkey) in the year 2001 and their relation to allergic diseases. J. Basic Microbiol. 2003, 43, 376–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troutt, C.; Levetin, E. Correlation of spring spore concentrations and meteorological conditions in Tulsa, Oklahoma. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2001, 45, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denning, D.W.; O’Driscoll, B.R.; Hogaboam, C.; Bowyer, P.; Niven, R.M. The link between fungi and severe asthma: A summary of the evidence. Eur. Respir. J. 2006, 27, 615–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Gracia, M.D.; Elizondo-Zertuche, M.; Orué, N.; Treviño-Rangel, R.D.J.; Rodríguez-Sánchez, I.P.; Adame-Rodríguez, J.M.; Zapata-Morín, P.A.; Robledo-Leal, E. Culturable airborne fungi in downtown Monterrey (Mexico) and their correlation with air pollution over a 12-month period. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baboli, Z.; Hayati, R.; Mosavion, K.; Goudarzi, M.; Sadeghi-Nejad, B.; Ghanbari, F.; Maleki, H.; Yazdani, M.; Davoudi, G.H.; Goudarzi, G. An evaluation of fungal contamination and its relationship with PM levels in public transportation systems. Environ. Res. 2024, 252, 118901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; He, Y.; Bu, H. Association between sensitization to common fungi and severe asthma. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1582643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trautmann, A.; Wuthrich, B.; Blaser, K.; Scheynius, A.; Crameri, R. IgE-mediated and T cell-mediated autoimmunity against manganese superoxide dismutase in atopic dermatitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2005, 115, 1068–1075. [Google Scholar]

- Kortekangas-Savolainen, O.; Lammintausta, K.; Kalimo, K. Skin prick test reactions to brewer’s yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) in adult atopic dermatitis patients. Allergy 1993, 48, 147–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jalili, D.; Dehghani, M.; Fadaei, A.; Alimohammadi, M. Assessment of airborne bacterial and fungal communities in Shahrekord hospitals. J. Environ. Public Health 2021, 2021, 8864051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardin, B.; Kelman, B.; Saxon, A. Adverse human health effects associated with molds in the indoor environment. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2003, 45, 470–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vonberg, R.; Gastmeier, P. Nosocomial aspergillosis in outbreak settings. J. Hosp. Infect. 2006, 63, 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hristova, D.; Kandova, Y.; Nikolov, G.; Petrunov, B. Sensitization to fungal allergens in patients with respiratory allergy–accuracy in diagnostic process. J. Microbiol. Epidemiol. Immunobiol. 2020, 97, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar, F.M.A.; Galala, A.A.; El-Sokkary, M.M.; Khalil, A.T.; Sallam, A. In vitro cytotoxicity and secondary metabolites of Talaromyces wortmannii isolated from Arundo donax L.: Identification of a new phytoceramide. Sci. Afr. 2025, 27, e02600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Dong, F.; Bao, F.; Chen, S.; Tian, H. Cutaneous mycosis caused by Talaromyces wortmannii: A novel fungal pathogen. J. Dtsch. Dermatol. Ges. 2024, 22, 1145–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Data | Temperature [°C] | Wind Speed [m/s] | Amount of Precipitation [mm] | Recorded Phenomena | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average | Min. | Wind Speed [m/s] | Av. | Max | Gusts of Wind | |||

| 29.03.2022 | 10.2 | 2.0 | 18.5 | 2.5 | 8 | - | 0 | - |

| 30.03.2022 | 11.1 | 0.0 | 19.0 | 2.4 | 7 | - | 0 | - |

| 31.03.2022 | 15.2 | 10.6 | 19.0 | 4 | 10 | 18 | 0 | Rain/Sleet |

| 01.04.2022 | 13.9 | 8.0 | 21.9 | 3.7 | 8 | 19 | 0 | Rain/Sleet, Thunderstorm |

| 02.04.2022 | 10.8 | 6.0 | 17.2 | 4.2 | 12 | 22 | 13.2 | Rain/Sleet, Thunderstorm |

| 03.04.2022 | 5.8 | 2.0 | 10.2 | 4.5 | 8 | - | 2.5 | Rain/Sleet |

| 04.04.2022 | 5.4 | 0.0 | 10.0 | 2.8 | 6 | - | 1 | Rain/Sleet |

| 05.04.2022 | 7.9 | 0.0 | 16.0 | 1.3 | 3 | - | 0 | - |

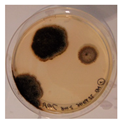

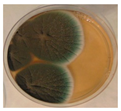

| Orlov Most | ||||

|  |  |  |  |

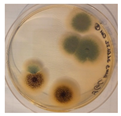

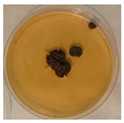

| NBU | ||||

|  |  |  |  |

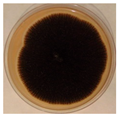

| Aspergillus | Aspergillus | Aspergillus | Epicoccum |

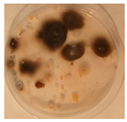

|  |  |  |

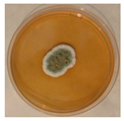

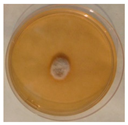

| Penicillium | Herpotrichia | Stereum | Trametes |

|  |  |  |

| Alternaria | Cladosporium | Talaromyces | Bjerkandera |

|  |  |  |

| № | Strain № | Identified as | GenBank Accession Number | Similarity to the Reference Strains, % | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | 6A1 | Alternaria alternata | PV771525 | 99.80%, Alternaria alternata CBS 102,600 | Orlov Most |

| 2. | 6A2 | Herpotrichia striatispora | PV771526 | 97%, Herpotrichia striatispora CBS 385.65 | Orlov Most |

| 3. | 6A9 | Alternaria angustiovoidea | PV771527 | 99.62% Alternaria angustiovoidea CBS 195.86 | Orlov Most |

| 4. | 7A1 | Aspergillus fumigatus | PV771528 | 99.23% Aspergillus fumigatus ATCC 1022 | Orlov Most |

| 5. | 7A2 | Alternaria alternata | PV771529 | 99.00% Alternaria alternata CBS 102,595 | Orlov Most |

| 6. | 8A2 | Talaromyces pinophilus | PV771530 | 99.0% Talaromyces pinophilus CBS 631.66 | Orlov Most |

| 7. | 8A3 | Talaromyces wortmannii | PV771531 | 99.42% Talaromyces wortmannii CBS 316.63 | Orlov Most |

| 8. | 8A4 | Aspergillus fumigatus | PV771532 | 99.46% Aspergillus fumigatus ATCC 1022 | Orlov Most |

| 9. | 9A1 | Alternaria tenuissima | PV771533 | 100% Alternaria tenuissima CBS 117.44 | Orlov Most |

| 10. | 9A2 | Coniothyrium telephii | PV771534 | 99.60% Coniothyrium telephii CBS 188.71 | Orlov Most |

| 11. | 18A2 | Alternaria infectoria | PV771535 | 99.44% Alternaria infectoria CBS 210.86 | Orlov Most |

| 12. | 23A2 | Cladosporium cladosporioides | PV771536 | 100% Cladosporium pseudocladosporioides CBS 126,356 | Orlov Most |

| 13. | 23A3 | Epicoccum nigrum | PV771537 | 99.59% Epicoccum nigrum CBS 236.59 | Orlov Most |

| 14. | 27A1 | Aspergillus fumigatus | PV771538 | 99.0% Aspergillus fumigatus ATCC 1022 | Orlov Most |

| 15. | 32A1 | Aspergillus fumigatus | PV771539 | 99.62% Aspergillus fumigatus ATCC 90,906 | NBU |

| 16. | 32A2 | Talaromyces wortmannii | PV771540 | 99.46% Talaromyces wortmannii CBS 316.63 | Orlov Most |

| 17. | 62A1 | Epicoccum nigrum | PV771541 | 100% Epicoccum nigrum CBS 173.73 | NBU |

| 18. | 76A2 | Alternaria tenuissima | PV771542 | 99.22% Alternaria tenuissima CBS 117.44 | NBU |

| 19. | 77A1 | Penicillium griseofulvum | PV771543 | 99.63% Penicillium griseofulvum CBS 185.27 | NBU |

| 20. | 83A1 | Alternaria caespitosa | PV771544 | 99.46% Alternaria caespitosa CBS 177.80 | NBU |

| 21. | 90A1 | Bjerkandera adusta | PV771545 | 99.83% Bjerkandera adusta CBS 371.52 | NBU |

| 22. | 92A1 | Stereum hirsutum | PV771546 | 99.65% Stereum hirsutum CBS 930.70 | NBU |

| 23. | 117A2 | Trametes ochracea | PV771547 | 99.82% Trametes ochracea CBS 287.33 | NBU |

| 24. | 126 | Bjerkandera adusta | PV771548 | 99.00% Bjerkandera adusta CBS 371.52 | NBU |

| Biodiversity | Shannon Index | Simpson Index | Sørensen Index |

|---|---|---|---|

| Orlov Most | 2338 | 6887 | 0.25 |

| NBU | 2042 | 7518 |

| Fungal Species | Nystatin—% of Growth Inhibition | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 h | 48 h | 72 h | 96 h | 7 Days | |||

| Ascomycota | Alternaria alternata 61 | 94.64 ± 1.73 | 91.12 ± 1.52 | 88.68 ± 1.19 | 84.18 ± 1.65 | 79.56 ± 2.1 | |

| Alternaria tenuissima 91 | 98.99 ± 1.58 | 92.97 ± 1.55 | 89.07 ± 1.49 | 87.72 ± 2.11 | 84.78 ± 2.06 | ||

| Alternaria infectoria 182 | 100 ± 0.5 | 100 ± 0.5 | 93.74 ± 2.03 | 86.1 ± 1.98 | 75 ± 1.97 | ||

| Alternaria sp. 63 | 96.89 ± 1.04 | 96.46 ± 1.70 | 92.12 ± 2.02 | 87.69 ± 1.76 | 85.57 ± 1.32 | ||

| Cladosporium cladosporioides 23′ | 96.64 ± 1.19 | 93.69 ± 2.56 | 88.52 ± 2.22 | 88 ± 1.98 | 80.66 ± 3.02 | ||

| Talaromyces wortmannii 83 | 97.17 ± 2.03 | 96.59 ± 1.98 | 96.48 ± 1.79 | 90.78 ± 2.45 | 83.68 ± 2.89 | ||

| Talaromyces pinophilus 82 | 94.39 ± 1.99 | 92.53 ± 2.04 | 87.16 ± 1.45 | 85.57 ± 1.93 | 82.83 ± 2.01 | ||

| Talaromyces pinophilus 82′ | 96.09 ± 1.23 | 95 ± 1.78 | 90.07 ± 3.06 | ||||

| Talaromyces wortmannii 322 | |||||||

| Penicillium griseofulvum 771 | 92.19 ± 2.67 | 88.17 ± 2.01 | 82.9 ± 1.88 | 82.79 ± 2.01 | 79.71 ± 3.34 | ||

| Stereum hirsutum 921 | 99.22 ± 1.56 | 86.95 ± 2.05 | 86.81 ± 1.97 | 83.49 ± 2.45 | 73.11 ± 2.76 | ||

| Herpotrichia striatispora 62 | 81.05 ± 3.78 | 78.12 ± 2.78 | 78.02 ± 3.02 | ||||

| Coniothyrium telephii 92 | 100 ± 0.6 | 100 ± 0.3 | 92.64 ±0.4 | ||||

| Aspergillus fumigates 84 | 88.43 ± 2.65 | 87.56 ± 1.88 | 86.12 ± 2.57 | ||||

| Epicoccum nigrum 621 | 91.89 ± 3.56 | 91.9 ± 3.01 | 91.96 ± 1.96 | 90.86 ± 1.42 | 90.51 ± 1.89 | ||

| Basidiomycota | Bjerkandera adusta 126 | 87.28 ± 3.12 | 87.48 ± 2.66 | 85.75 ±2.08 | 86.22 ± 1.35 | 84.37 ± 1.87 | |

| Trametes ochracea 1172 | 100 ± 0.72 | 100 ± 0.55 | 71.22 ± 2.35 | 68.34 ± 1.79 | |||

| Bjerkandera adusta 901 | 93.63 ± 1.33 | 91.59 ± 2.21 | 91.67 ± 1.99 | 88.06 ± 0.89 | 88.79 ± 1.56 | ||

| Legend | 95–100% | ||||||

| 90–94.99% | |||||||

| 80–89.99% | |||||||

| 60–79.99% | |||||||

| Fungal Species | Amphotericin—% of Growth Inhibition | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 h | 48 h | 72 h | 96 h | 7 Days | ||

| Ascomycota | Alternaria alternata 61 | 89.21 ± 2.34 | 87.41 ± 1.99 | 84.45 ± 3.12 | 82.09 ± 1.23 | 80.72 ± 3.21 |

| Alternaria tenuissima 91 | 90.18 ± 3.21 | 86.35 ± 2.06 | 85.95 ± 2.22 | 83.81 ± 1.63 | ||

| Alternaria infectoria 182 | 100 ± 0.3 | 100 ± 0.5 | 90.97 ± 2.57 | 89.88 ± 0.94 | ||

| Alternaria sp. 63 | 89.72 ± 4.33 | 87.66 ± 2.78 | 88.11 ± 1.50 | 91.87 ± 1.50 | ||

| Cladosporium cladosporioides 23′ | 90.38 ± 2.87 | 88.53 ± 1.68 | 88.63 ± 1.77 | 87.24 ± 2.16 | 85.57 ± 3.01 | |

| Talaromyces wortmannii 83 | ||||||

| Talaromyces pinophilus 82 | 93.54 ± 3.01 | 92.47 ± 1.56 | 89.21 ± 2.12 | 86.32 ± 1.29 | ||

| Talaromyces pinophilus 82′ | 91.88 ± 2.79 | 88 ± 1.99 | 87.84 ± 1.45 | 87.23 ± 2.76 | ||

| Talaromyces wortmannii 322 | 91.46 ± 1.66 | 87.32 ± 2.03 | 84.67 ± 2.36 | 84.85 ± 1.44 | ||

| Penicillium griseofulvum 771 | 92.14 ± 1.98 | 86.29 ± 2.42 | 80.17 ± 1.45 | 80.52 ± 2.52 | ||

| Stereum hirsutum 921 | 96.63 ± 2.04 | 94.03 ± 1.69 | 93.98 ± 1.72 | 91.71 ± 3.44 | 90.03 ± 1.59 | |

| Herpotrichia striatispora 62 | 93.09 ± 2.26 | 89.59 ± 2.17 | 88.59 ± 1.94 | 77.27 ± 3.94 | ||

| Coniothyrium telephii 92 | 79.84 ± 4.98 | 78 ± 1.88 | 77.36 ± 2.46 | |||

| Aspergillus fumigates 84 | 90.48 ± 1.33 | 90.31 ± 1.76 | 90.22 ± 2.34 | 89.16 ± 2.45 | ||

| Epicoccum nigrum 621 | 94.11 ± 1.79 | 93.87 ± 2.03 | 92.75 ± 1.23 | 78.72 ± 4.02 | ||

| Basidiomycota | Bjerkandera adusta 126 | 87.99 ± 2.65 | 87.59 ± 1.95 | 86.35 ± 2.51 | 83.77 ± 3.21 | 81.31 ± 2.35 |

| Trametes ochracea 1172 | 89.93 ± 1.57 | 89.88 ± 1.83 | 89.64 ± 1.63 | 89.59 ± 2.33 | 89.53 ± 2.62 | |

| Bjerkandera adusta 901 | 87.9 ± 2.17 | 86.38 ± 1.54 | 78.56 ± 2.05 | 76.13 ± 1.89 | 62.7 ± 2.25 | |

| Legend | 95–100% | |||||

| 90–94.99% | ||||||

| 80–89.99% | ||||||

| 60–79.99% | ||||||

| Fungal Strain | MIC mg/mL | |

|---|---|---|

| Nystatin | Amphotericin | |

| Alternaria alternata 61 | 0.18 | 0.042 |

| Herpotrichia striatispora 62 | 0.042 | 0.18 |

| Alternaria sp. 63 | 0.18 | 0.18 |

| Talaromyces sp. 82 | 0.042 | 0.085 |

| Talaromyces pinophilus 82′ | 0.18 | 0.18 |

| Talaromyces wortmannii 83 | 0.18 | resistant |

| Aspergillus fumigates 84 | 0.18 | 0.18 |

| Alternaria tenuissima 91 | 0.042 | 0.042 |

| Coniothyrium telephii 92 | 0.36 | 0.36 |

| Alternaria infectoria 182 | 0.36 | 0.36 |

| Cladosporium cladosporioides 23′ | 0.085 | 0.18 |

| Talaromyces wortmannii 322 | resistant | 0.18 |

| Epicoccum nigrum 621 | 0.042 | 0.085 |

| Penicillium griseofulvum 771 | 0.36 | 0.18 |

| Bjerkandera adusta 901 | 0.36 | 0.18 |

| Stereum hirsutum 921 | 0.042 | 0.36 |

| Trametes ochracea 1172 | 0.042 | 0.18 |

| Bjerkandera adusta 126 | 0.042 | 0.042 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ivanova, M.; Stoyancheva, G.; Dishliyska, V.; Miteva-Staleva, J.; Abrashev, R.; Spasova, B.; Gocheva, Y.; Yovchevska, L.; Satchanska, G.; Angelova, M.; et al. Composition and Occurrence of Airborne Fungi in Two Urbanized Areas of the City of Sofia, Bulgaria. Appl. Microbiol. 2025, 5, 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/applmicrobiol5030096

Ivanova M, Stoyancheva G, Dishliyska V, Miteva-Staleva J, Abrashev R, Spasova B, Gocheva Y, Yovchevska L, Satchanska G, Angelova M, et al. Composition and Occurrence of Airborne Fungi in Two Urbanized Areas of the City of Sofia, Bulgaria. Applied Microbiology. 2025; 5(3):96. https://doi.org/10.3390/applmicrobiol5030096

Chicago/Turabian StyleIvanova, Margarita, Galina Stoyancheva, Vladislava Dishliyska, Jeny Miteva-Staleva, Radoslav Abrashev, Boryana Spasova, Yana Gocheva, Lyudmila Yovchevska, Galina Satchanska, Maria Angelova, and et al. 2025. "Composition and Occurrence of Airborne Fungi in Two Urbanized Areas of the City of Sofia, Bulgaria" Applied Microbiology 5, no. 3: 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/applmicrobiol5030096

APA StyleIvanova, M., Stoyancheva, G., Dishliyska, V., Miteva-Staleva, J., Abrashev, R., Spasova, B., Gocheva, Y., Yovchevska, L., Satchanska, G., Angelova, M., & Krumova, E. (2025). Composition and Occurrence of Airborne Fungi in Two Urbanized Areas of the City of Sofia, Bulgaria. Applied Microbiology, 5(3), 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/applmicrobiol5030096