Application of Trichoderma spp. to Control Colletotrichum sp. and Pseudopestalotiopsis spp., Causing Agents of Fruit Rot in Pomelo (Citrus maxima (Burm.) Merr.)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Isolation of Fungi Causing Pomelo Rot in Ben Tre

2.2.2. Isolation and Selection of Trichoderma spp. Fungi with the Ability to Antagonize Colletotrichum sp. and Pseudopestalotiopsis spp. Causing Fruit Rot Disease on Pomelos in Ben Tre

2.2.3. Antagonistic Ability of Trichoderma spp. Against Pathogenic Fungi

2.3. Data Processing

3. Results

3.1. Isolation of Fungi Causing Pomelo Fruit Rot Disease in Ben Tre

3.1.1. Morphological Characteristics of Fungal Strains Causing Pomelo Fruit Rot

3.1.2. Growth of Fungal Strains Causing Pomelo Fruit Rot on PDA Medium

3.1.3. Morphological Classification of Fungal Strains Causing Pomelo Fruit Rot

3.1.4. Evaluation of the Pathogenicity of Selected Fungal Strains

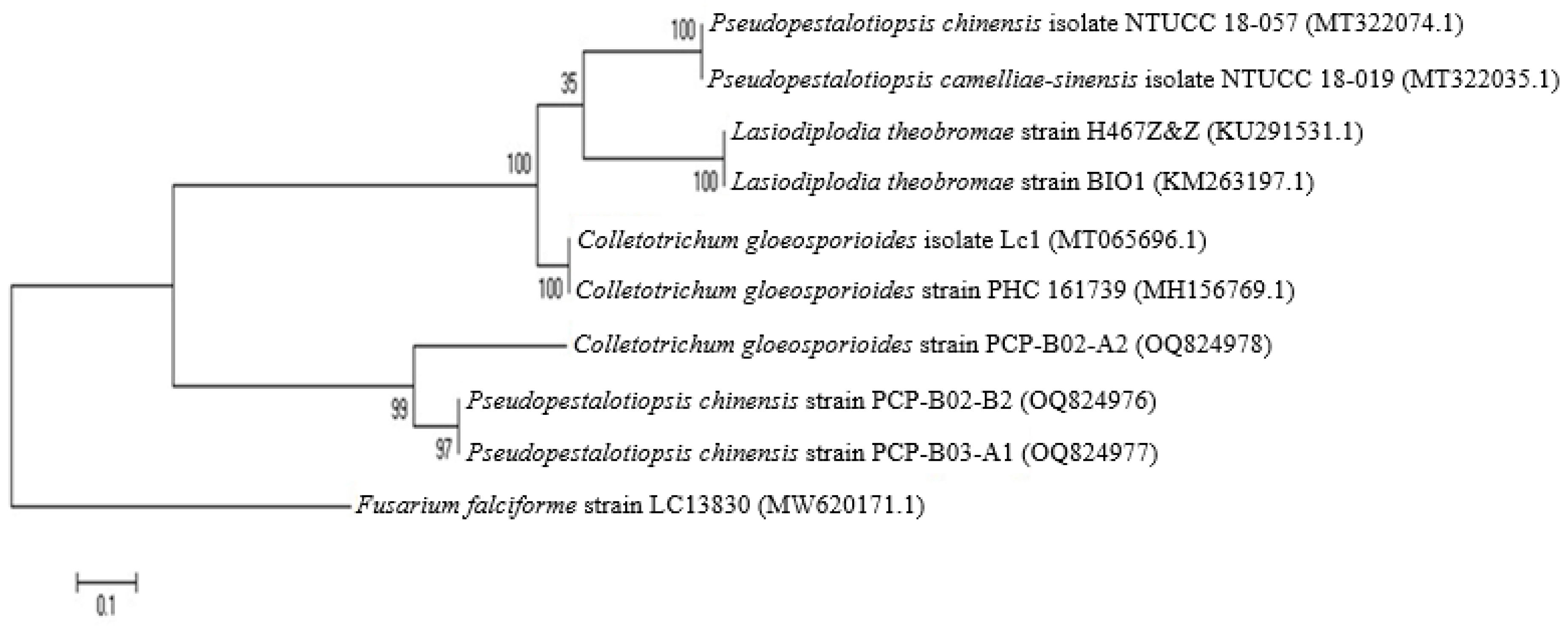

3.1.5. Identification of Fungi Causing Pomelo Fruit Rot

3.2. Isolation of Trichoderma spp. from Pomelo Farms in Ben Tre

3.2.1. Isolation of Trichoderma spp. from Pomelo Cultivation Soil

3.2.2. Growth of Trichoderma spp. on PDA Medium

3.3. Antagonistic Ability of Trichoderma spp. Against Fruit Rot Fungi

3.3.1. Antagonistic Ability of Trichoderma spp. Against Colletotrichum gloeosporioides PCP-B02-A2 on PDA Medium

3.3.2. Antagonistic Ability of Trichoderma spp. Against Pseudopestalotiopsis chinensis PCP-B02-B2 on PDA Medium

3.3.3. Antagonistic Ability of Trichoderma spp. Against Pseudopestalotiopsis camelliae-sinensis PCP-B03-A1 on PDA Medium

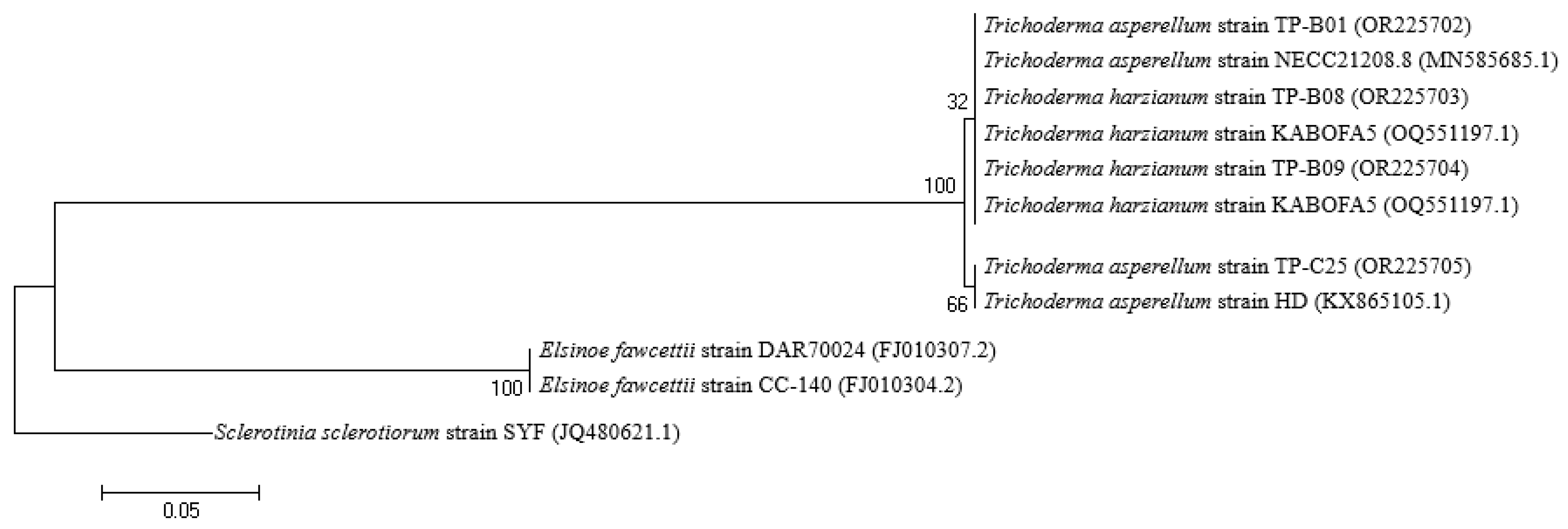

3.4. Identification of Trichoderma spp. Fungi that can Antagonize Fungi Causing Pomelo Fruit Rot

3.5. Ability to Produce Enzymes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ITS | Internal Transcribed Spacer |

| PCR | Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| PDA | Potato Dextrose Agar |

| TSM | Trichoderma Selective Medium |

References

- Methacanon, P.; Krongsin, J.; Gamonpilas, C. Pomelo (Citrus Maxima) pectin: Effects of extraction parameters and its properties. Food Hydrocoll. 2013, 35, 383–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, T.B.; Muoi, N.V.; Tuoi, N.T.K.; Toan, H.T. Determination of physico-chemical characteristics of da xanh (Citrus maxima) and nam roi (Citrus grandis L.) pomelo by weight. Can Tho Univ. J. Sci. 2023, 59, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swamy, C.T.; Sivadurga, K.; Reddy, M.P.; Marimuthu, G.; Prashantkumar, C.S.; Premkumar, C.; Purewal, S.S. Citrus waste: A treasure of promised phytochemicals and its nutritional-nutraceutical value in health promotion and industrial applications. In Recent Advances in Citrus Fruits; Singh Purewal, S., Punia Bangar, S., Kaur, P., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 395–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narasimha Rao, S.; Bhattiprolu, S.L.; Prasanna Kumari, V.; Vijaya Gopal, A. Cultural and morphological variability in Colletotrichum lindemuthianum (Sacc. and Magn.) causing anthracnose of field bean. Pharma. Innov. J. 2022, 11, 212–222. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Sui, Y.; Li, J.; Tian, X.; Wang, Q. Biological control of postharvest fungal decays in citrus: A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 62, 861–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maharachchikumbura, S.S.N.; Hyde, K.D.; Groenewald, J.Z.; Xu, J.; Crous, P.W. Pestalotiopsis revisited. Stud. Mycol. 2014, 79, 121–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Mi, X.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, L.; Wei, C. Characterization and pathogenicity of Pestalotiopsis-like species associated with gray blight disease on Camellia sinensis in Anhui Province, China. Plant Dis. 2019, 103, 2786–2797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darapanit, A.; Boonyuen, N.; Leesutthiphonchai, W.; Nuankaew, S.; Piasai, O. Identification, Pathogenicity and effects of plant extracts on Neopestalotiopsis and Pseudopestalotiopsis causing fruit diseases. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 22606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Liu, M.; Liu, L.; Tang, Z.; Dan, Y.; Cui, X.; Yin, F. First report of Pseudopestalotiopsis theae causing leaf spot on Euonymus japonicus in China. Plant Dis. 2022, 107, 1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahriar, S.A.; Nur-Shakirah, A.O.; Mohd, M.H. Neopestalotiopsis clavispora and Pseudopestalotiopsis camelliae-sinensis causing grey blight disease of tea (Camellia sinensis) in Malaysia. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2021, 162, 709–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Blay, V.; Pérez-Gago, M.B.; De La Fuente, B.; Carbó, R.; Palou, L. Edible coatings formulated with antifungal GRAS salts to control citrus anthracnose caused by Colletotrichum gloeosporioides and preserve postharvest fruit quality. Coatings 2020, 10, 730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, F.V.; Herrmann-Andrade, A.M.; Calabrese, C.D.; Bello, F.; Vázquez, D.; Musumeci, M.A. Effectiveness of Trichoderma strains isolated from the rhizosphere of citrus tree to control Alternaria alternata, Colletotrichum gloeosporioides and Penicillium digitatum A21 resistant to Pyrimethanil in post-harvest oranges (Citrus sinensis L. (Osbeck)). J. Appl. Microbiol. 2020, 129, 712–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penet, L.; Guyader, S.; Pétro, D.; Salles, M.; Bussière, F. Direct splash dispersal prevails over indirect and subsequent spread during rains in Colletotrichum ghloeosporioides infecting yams. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e115757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drenth, A.; Guest, D.I. 7.1 Principles of phytophthora disease management. In Diversity and Management of Phytophthora in Southeast Asia; Drenth, A., Guest, D.I., Eds.; ACIAR Monograph: Canberra, Australia, 2004; pp. 154–160. [Google Scholar]

- Ayaz, M.; Li, C.-H.; Ali, Q.; Zhao, W.; Chi, Y.-K.; Shafiq, M.; Ali, F.; Yu, X.-Y.; Yu, Q.; Zhao, J.-T.; et al. Bacterial and fungal biocontrol agents for plant disease protection: Journey from lab to field, current status, challenges, and global perspectives. Molecules 2023, 28, 6735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Contreras-Cornejo, H.A.; Macías-RodríGuez, L.; Cortés-Penagos, C.; López-Bucio, J. Trichoderma virens, a plant beneficial fungus, enhances biomass production and promotes lateral root growth through an auxin-dependent mechanism in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2009, 149, 1579–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sood, M.; Kapoor, D.; Kumar, V.; Sheteiwy, M.S.; Ramakrishnan, M.; Landi, M.; Araniti, F.; Sharma, A. Trichoderma: The “Secrets” of a multitalented biocontrol agent. Plants 2020, 9, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, A.O.; De Mio, L.L.M.; Soccol, C.R. Trichoderma as a powerful fungal disease control agent for a more sustainable and healthy agriculture: Recent studies and molecular insights. Planta 2023, 257, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, S.L.; Hermosa, R.; Lorito, M.; Monte, E. Trichoderma: A multipurpose, plant-beneficial microorganism for eco-sustainable agriculture. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2022, 21, 312–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, Y.; Ribera, J.; Schwarze, F.W.M.R.; De France, K. Biotechnological development of Trichoderma-based formulations for biological control. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2023, 107, 5595–5612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zin, N.A.; Badaluddin, N.A. Biological functions of Trichoderma spp. for agriculture applications. Ann. Agric. Sci. 2020, 65, 168–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madbouly, A.K. Biodiversity of genus Trichoderma and their potential applications. In Industrially Important Fungi for Sustainable Development. Fungal Biology; Abdel-Azeem, A.M., Yadav, A.N., Yadav, N., Usmani, Z., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 429–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bargaz, A.; Lyamlouli, K.; Chtouki, M.; Zeroual, Y.; Dhiba, D. Soil microbial resources for improving fertilizers efficiency in an integrated plant nutrient management system. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinale, F.; Nigro, M.; Sivasithamparam, K.; Flematti, G.; Ghisalberti, E.L.; Ruocco, M.; Varlese, R.; Marra, R.; Lanzuise, S.; Eid, A.; et al. Harzianic acid: A novel siderophore from Trichoderma harzianum. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2013, 347, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Sharma, D.D.; Babu, A.M.; Datta, R.K. SEM studies on the hyphal interaction between a biocontrol agent Tharzianum and mycopathogen Fusarium causing root rot disease in mulberry. Ind. J. Seric. 1998, 37, 17–20. [Google Scholar]

- Brotman, Y.; Kapuganti, J.G.; Viterbo, A. Trichoderma. Curr. Biol. 2010, 20, R390–R391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gow, N.A.R.; Lenardon, M.D. Architecture of the dynamic fungal cell wall. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2022, 21, 248–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gow, N.A.R.; Latge, J.-P.; Munro, C.A. The fungal cell wall: Structure, biosynthesis, and function. Microbiol. Spectr. 2017, 5, 267–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, R.; Kalia, A.; Lore, J.S.; Kaur, A.; Yadav, I.; Sharma, P.; Sandhu, J.S. Trichoderma sp. Endochitinase and Β-1,3-glucanase impede Rhizoctonia solani growth independently, and their combined use does not enhance impediment. Plant Pathol. 2021, 70, 1388–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holkar, S.K.; Ghotgalkar, P.S.; Lodha, T.D.; Bhanbhane, V.C.; Shewale, S.A.; Markad, H.; Shabeer, A.T.P.; Saha, S. Biocontrol potential of endophytic fungi originated from grapevine leaves for management of anthracnose disease caused by Colletotrichum gloeosporioides. 3 Biotech 2023, 13, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruangwong, O.-U.; Pornsuriya, C.; Pitija, K.; Sunpapao, A. Biocontrol mechanisms of Trichoderma koningiopsis PSU3-2 against postharvest anthracnose of chili pepper. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.; Borah, S.M.; Borah, P.K.; Bora, P.; Sarmah, B.K.; Lal, M.K.; Tiwari, R.K.; Kumar, R. Deciphering the antimicrobial activity of multifaceted rhizospheric biocontrol agents of Solanaceous crops Viz., Trichoderma harzianum MC2, and Trichoderma harzianum NBG. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1141506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khuong, N.Q.; Nhien, D.B.; Thu, L.T.M.; Trong, N.D.; Hiep, P.C.; Thuan, V.M.; Quang, L.T.; Thuc, L.V.; Xuan, D.T. Using Trichoderma asperellum to antagonize Lasiodiplodia theobromae causing stem-end rot disease on pomelo (Citrus maxima). J. Fungi 2023, 9, 981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, X.T.; Tran, V.T. Isolation and characterization of Trichoderma strains antagonistic against pathogenic fungi on orange crops. Vietnam Natl. Univ. J. Sci. Nat. Sci. Technol. 2020, 36, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvia, M. Application of Trichoderma as an alternative to the use of sulfuric acid pesticides in the control of Diplodia disease on pomelo citrus. IOP Confer. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 819, 012007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, L.W.; Knight, T.E.; Tesoriero, L.; Phan, H.T. Diagnostic Manual for Plant Diseases in Vietnam; ACIAR Monograph: Canberra, Australia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Roger, S.; Beasley, D. Management of Plant Pathogen Collections; Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry: Queensland, Australia, 2005.

- Klich, M.A. Identification of Common Aspergillus Species; Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, K.; Amaresan, N.; Bhagat, S.; Madhuri, K.; Srivastava, R.C. Isolation and characterization of Trichoderma spp. for Antagonistic activity against root rot and foliar pathogens. Indian J. Microbiol. 2011, 52, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doyle, J.J.; Doyle, J.L. A rapid DNA isolation procedure for small quantities of fresh leaf tissue. Phytochem. Bull. 1987, 19, 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- White, T.J.; Bruns, T.; Lee, S.; Taylor, J. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In PCR Protocols: A Guide to Methods and Applications; Innis, M.A., Gelfand, D.H., Sninsky, J.J., White, T.J., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1990; pp. 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, D.K.; Wells, H.D.; Markham, C.R. In vitro antagonism of Trichoderma species against six fungal plant pathogens. Phytopathology 1982, 72, 379–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakraliya, S.S.; Zacharia, S.; Bajiya, M.R.; Sheshma, M. Management of leaf blight of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) with bio-agents, neem leaf extract and fungicides. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2017, 6, 296–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zhang, J. Lasiodiplodia theobromae in citrus fruit (Diplodia stem-end rot). In Postharvest Decay; Bautista-Baños, S., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014; pp. 309–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awan, Q.N.; Akgül, D.S.; Unal, G. First report of Lasiodiplodia pseudotheobromae causing postharvest fruit rot of lemon in Turkey. Plant Dis. 2016, 100, 2327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhu, Z.; Fu, Y.; Cheng, J.; Xie, J.; Lin, Y. Identification of Lasiodiplodia pseudotheobromae causing fruit rot of citrus in China. Plants 2021, 10, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juge, N. Plant protein inhibitors of cell wall degrading enzymes. Trends Plant Sci. 2006, 11, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terefe, N.S.; Gamage, M.; Vilkhu, K.; Simons, L.; Mawson, R.; Versteeg, C. The kinetics of inactivation of pectin methylesterase and polygalacturonase in tomato juice by thermosonication. Food Chem. 2009, 117, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, S.; Lin, H.; Lu, W.; Wang, H.; Chen, Y.; Lin, Y.; Fan, Z. The role of cell wall polysaccharides disassembly in Lasiodiplodia theobromae-induced disease occurrence and softening of fresh longan fruit. Food Chem. 2021, 351, 129294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, J.; Feichtenberger, E. Citrus Phytophthora diseases: Management challenges and successes. J. Citrus Pathol. 2015, 2, 27203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerioni, L.; Bennasar, P.B.; Lazarte, D.; Sepulveda, M.; Smilanick, J.L.; Ramallo, J.; Rapisarda, V.A. Conventional and reduced-risk fungicides to control postharvest Diplodia and Phomopsis stem-end rot on lemons. Sci. Hortic. 2017, 225, 783–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musheer, N.; Ashraf, S. Effect of Trichoderma spp. on Colletotrichum gleosporiodes Penz and Sacc. causal organism of Turmeric leaf spot disease. Trends Biosci. 2017, 10, 9605–9608. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmmed, M.S.; Sikder, M.M.; Sarker, S.R.; Hossain, M.S.; Shubhra, R.D.; Alam, N. First Report of Pseudopestalotiopsis theae Causing Aloe Vera Leaf Spot Disease in Bangladesh. Am. J. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nujthet, Y.; Kaewkrajay, C.; Kijjoa, A.; Dethoup, T. Biocontrol Efficacy of Antagonists Trichoderma and Bacillus against Post-Harvest Diseases in Mangos. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2024, 168, 315–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Los Santos-Villalobos, S.; Guzmán-Ortiz, D.A.; Gómez-Lim, M.A.; Délano-Frier, J.P.; De-Folter, S.; Sánchez-García, P.; Peña-Cabriales, J.J. Potential use of Trichoderma asperellum (Samuels, Liechfeldt et Nirenberg) T8a as a biological control agent against Anthracnose in mango (Mangifera indica L.). Biol. Control 2012, 64, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaverri, P.; Samuels, G.J. Hypocrea/Trichoderma (Ascomycota, Hypocreales, Hypocreaceae): Species with Green Ascospores; Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Q.; Sun, R.; Ni, M.; Yu, J.; Li, Y.; Yu, C.; Dou, K.; Ren, J.; Chen, J. Identification of a novel fungus, Trichoderma asperellum GDFS1009, and comprehensive evaluation of its biocontrol efficacy. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0179957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucuk, C.; Kivanc, M. Mycoparasitism in the biological control of Gibberella zeae and Aspergillus ustus by Trichoderma harzianum strains. J. Agric. Technol. 2008, 4, 49–55. [Google Scholar]

- Rajendiran, R.; Jegadeeshkumar, D.; Sureshkumar, B.T.; Nisha, T. In vitro assessment of antagonistic activity of Trichoderma viride against post harvest pathogens. J. Agric. Technol. 2010, 6, 31–35. [Google Scholar]

- Padder, B.A.; Sharma, P.N. In vitro and in vivo antagonism of biocontrol agents against Colletotrichum lindemuthianum causing bean anthracnose. Arch. Phytopathol. Plant Prot. 2011, 44, 961–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Wang, X.; Feng, G.-D.; Yao, Q.; Zhu, H. A Novel Strain Burkholderia theae GS2Y Exhibits Strong Biocontrol Potential against Fungal Diseases in Tea Plants (Camellia sinensis). Cells 2024, 13, 1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guzmán-Guzmán, P.; Kumar, A.; de los Santos-Villalobos, S.; Parra-Cota, F.I.; Orozco-Mosqueda, M.D.C.; Fadiji, A.E.; Hyder, S.; Babalola, O.O.; Santoyo, G. Trichoderma Species: Our Best Fungal Allies in the Biocontrol of Plant Diseases—A Review. Plants 2023, 12, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Widyaningsih, S.; Triasih, U. Biological Control of Strawberry Crown Rot Disease (Pestalotiopsis sp.) Using Trichoderma harzianum and Endophytic Bacteria. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 752, 012052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.; Bhandari, A. (Eds.) Bio-management of Postharvest Diseases and Mycotoxigenic Fungi, 1st ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020; ISBN 978-1003089223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kredics, L.; Büchner, R.; Balázs, D.; Allaga, H.; Kedves, O.; Racić, G.; Varga, A.; Nagy, V.D.; Vágvölgyi, C.; Sipos, G. Recent Advances in the Use of Trichoderma-Containing Multicomponent Microbial Inoculants for Pathogen Control and Plant Growth Promotion. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 40, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Strain | Shape | Surface Shape | Surface Color | Diameter (cm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCP-B02-A2 | Evenly radiated | The center of the fungus was pinkish white, raised, and winding in a wavy shape | White-gray, initially pinkish | 4.35 |

| PCP-B02-B1 | Almost round | The black and gray center then wander out evenly | Blackish gray | 8.80 |

| PCP-B02-B2 | Almost round to round | Hyphae grew thick and raised | Creamy white | 4.57 |

| PCP-B02-C1 | Evenly rounded | In the form of cotton foam, hyphae protrude from the medium | Gray | 8.90 |

| PCP-B02-C2 | Radiance | The center of the fungus was initially black, then spread evenly | Darkish gray | 90 |

| PCP-B02-D1 | Almost round | The hyphae grew thick with blackish hyphae | Blackish gray | 8.70 |

| PCP-B03-A1 | Spread evenly to almost round | The white hyphae were as porous as cotton, rising and then radiating | Milky white, light yellow in the center | 6.72 |

| PCP-B03-A2 | Evenly rounded | White hyphae grew thickly, gradually turned gray | Light gray | 90 |

| PCP-B15-A2 | Almost round | Mycelia thickened and raised to form circles | Creamy white | 6.25 |

| PCP-B17-A1 | Radiance | Thick hyphae grew close to the medium | Gray | 8.95 |

| PCP-B17-A2 | Almost round | Mycelia grew thickly and were sticking to the medium | Blackish brown | 8.54 |

| PCP-B17-B2 | Radiance | The hyphae grew thickly, protruding from the medium | Grayish white | 8.90 |

| PCP-B17-C1 | Evenly rounded | White hyphae spreads evenly | Gray | 8.95 |

| PCP-B17-C2 | Evenly rounded | Thick and silky mycelia | Black interspersed with gray | 90 |

| PCP-B17-D1 | Radiance | Hyphae grew tightly together | Light gray | 90 |

| PCP-B17-D2 | Almost round | The center of the fungus was initially black, then spread outward. | Darkish gray | 8.75 |

| PCP-C02-A1 | Evenly rounded | Mycelia grew in a circle, beyond the edge of the colony protruding | Black interspersed with gray | 8.90 |

| PCP-C02-A2 | Evenly radiated | Blackish brown to black from the center to the edge of the plate, fungal foci appeared | Blackish gray | 8.85 |

| PCP-C08-A1 | Almost round | White alternating with irregular blackish brown | Blackish brown | 8.70 |

| Fungus Strain | Growth Rate of Fungal Strain (cm) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 24 h | 48 h | 72 h | |

| PCP-B02-A2 | 1.55 g | 2.75 j | 3.65 g |

| PCP-B02-B1 | 4.60 b | 7.40 d–f | 8.50 e |

| PCP-B02-B2 | 1.13 h | 2.73 k | 3.55 g |

| PCP-B02-C1 | 4.05 cd | 7.45 c–f | 8.80 ab |

| PCP-B02-C2 | 4.05 cd | 7.66 bc | 8.55 de |

| PCP-B02-D1 | 3.67 e | 7.65 bc | 8.65 b–e |

| PCP-B03-A1 | 1.15 h | 2.65 l | 3.25 i |

| PCP-B03-A2 | 4.55 b | 7.50 b–e | 8.80 ab |

| PCP-B15-A2 | 0.64 i | 2.70 l | 5.35 f |

| PCP-B17-A1 | 5.20 a | 7.60 b–d | 8.75 a–c |

| PCP-B17-A2 | 3.57 e | 7.70 ab | 8.85 a |

| PCP-B17-B2 | 5.25 a | 7.25 fg | 8.50 e |

| PCP-B17-C1 | 2.67 f | 7.90 a | 8.55 de |

| PCP-B17-C2 | 2.46 f | 7.05 gh | 8.65 b–e |

| PCP-B17-D1 | 3.80 de | 7.50 b–e | 8.60 c–e |

| PCP-B17-D2 | 4.15 c | 7.30 ef | 8.50 e |

| PCP-C02-A1 | 3.65 e | 7.50 b–e | 8.70 a–d |

| PCP-C02-A2 | 4.70 b | 6.80 i | 8.30 f |

| PCP-C08-A1 | 4.50 b | 6.95 hi | 8.65 b–e |

| F | * | * | * |

| CV (%) | 8.20 | 5.10 | 3.00 |

| Fungus Strain | Length of Lesions (mm) on the Fruit in Days After Infection | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 7 | Day 9 | Day 12 | Day 14 | Day 17 | |

| PCP-B02-A2 | 12.3 | 14.2 b | 18.2 b | 21.8 b | nd |

| PCP-B02-B2 | 12.8 | 14.1 b | 15.5 c | 16.6 c | 17.5 b |

| PCP-B03-A1 | 11.8 | 16.7 a | 19.9 a | 23.9 a | 28.1 a |

| F | ns | * | * | * | * |

| CV (%) | 10.4 | 10.2 | 7.13 | 9.27 | 3.83 |

| Strain Name | Shape | Surface Shape | Surface Color | Diameter (cm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TP-B01 | Radiance | Light green granules, forming concentric circles | Green, white | 8.90 |

| TP-B02 | Almost round | Green mixed with yellow granules | Green, light yellow | 9.0 |

| TP-B03 | Almost round to round | In the form of green granules, the center of the fungus forms a silky white circle | Green, white | 9.0 |

| TP-B04 | Evenly rounded | In the form of green granules, radiating evenly to form concentric circles | Dark green | 8.70 |

| TP-B05 | Radiance | White, thickly grown, alternating green hyphae | White, green | 9.0 |

| TP-B06 | Uneven roundness | Fine green granules, the center of the mycelia was white | Dark green, white | 8.85 |

| TP-B07 | Evenly rounded | Green granules, alternating white | Green, White | 8.90 |

| TP-B08 | Evenly radiated | Granules were green, white and light yellow | Light yellow, white | 9.0 |

| TP-B09 | Round to near-round | In the form of granules, the center of the colony was green, alternating in the middle of the hyphae with white | Green, White | 9.0 |

| TP-B10 | Evenly radiated | Silky, thickly grown mycelia with a light yellowish color mixed with green | Green, white, light yellow | 8.80 |

| TP-B11 | Uneven roundness | Green granular form | Dark green, white | 9.0 |

| TP-B12 | Uneven roundness | In the form of green hyphae, the hyphae radiated unevenly | Green | 8.90 |

| TP-G13 | Radiance | White hyphae with green granules in the middle | Green, White | 8.95 |

| TP-G14 | Almost round | White granules mixed with green granules | White, green center | 8.86 |

| TP-G15 | Evenly radiated | Light yellow hyphae mixed with white hyphae, scattered fungus grew thickly adhering to the medium | Brownish yellow, white | 9.0 |

| TP-G16 | Uneven roundness | Fine granular form with a dark green color | Dark green | 9.0 |

| TP-G17 | Radiance | In the form of green granules, around the center of the fungus there were protruding white hyphae | Green alters white, green in the center | 8.85 |

| TP-G18 | Almost round to round | White mixed with yellowish green hyphae | Light green, yellow-brown, white | 8.90 |

| TP-G19 | Uneven roundness | White hyphae thickly grew around the border with green granules | White, green, and green center | 9.0 |

| TP-C20 | Almost round | The hyphae were green mixed with white | Green, white | 8.70 |

| TP-C21 | Almost round to round | Green granules, with raised colony margins | Green, white | 8.90 |

| TP-C22 | Round to round | In the form of green granules, the center of the fungus had white granules | Dark green mixed with white | 9.0 |

| TP-C23 | Evenly rounded | Light yellow hyphae, the center of the fungi had green granules | Yellow-brown, green center | 9.0 |

| TP-C24 | Evenly radiated | White hyphae densely grew around the border with green granules | White, green | 8.90 |

| TP-C25 | Radiance | Dense white hyphae gradually turned green | White mixed with green | 9.0 |

| Fungal Strain | Growth Rate of Fungal Strain (cm) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 24 h | 48 h | 72 h | |

| TP-B01 | 3.56 a–c | 7.76 a | 8.70 ab |

| TP-B02 | 3.06 e–g | 7.36 d–f | 8.63 ab |

| TP-B03 | 2.80 hi | 6.90 hi | 8.76 ab |

| TP-B04 | 2.36 j | 5.20 n | 7.90 e |

| TP-B05 | 3.63 a–c | 7.63 a–c | 8.80 ab |

| TP-B06 | 3.50 bc | 7.60 a–d | 8.36 c |

| TP-B07 | 2.43 j | 5.56 m | 8.20 cd |

| TP-B08 | 3.20 ef | 7.10 gh | 8.66 ab |

| TP-B09 | 2.66 i | 7.30 e–g | 8.80 ab |

| TP-B10 | 2.90 gh | 7.50 b–e | 8.66 ab |

| TP-B11 | 3.13 ef | 6.56 k | 8.30 cd |

| TP-B12 | 3.76 a | 7.80 a | 8.70 ab |

| TP-G13 | 3.70 ab | 7.60 a–d | 8.76 ab |

| TP-G14 | 3.50 bc | 7.70 ab | 8.70 ab |

| TP-G15 | 3.20 ef | 7.20 fg | 8.33 cd |

| TP-G16 | 2.16 k | 5.86 l | 7.60 f |

| TP-G17 | 3.03 fg | 6.80 ij | 8.26 cd |

| TP-G18 | 3.26 de | 7.40 c–f | 8.60 b |

| TP-G19 | 3.56 a–c | 7.83 a | 8.60 b |

| TP-C20 | 2.80 hi | 5.36 mn | 7.30 g |

| TP-C21 | 3.10 ef | 6.63 jk | 8.36 c |

| TP-C22 | 2.66 i | 6.86 i | 8.16 d |

| TP-C23 | 3.43 cd | 7.20 fg | 8.36 c |

| TP-C24 | 3.66 ab | 7.76 a | 8.66 ab |

| TP-C25 | 3.73 a | 7.66 ab | 8.83 a |

| F | * | * | * |

| CV (%) | 5.05 | 3.61 | |

| Fungal Strain | Antagonistic Efficiency (%) | Diameter of Colletotrichum gloeosporioides PCP-B02-A2 (cm) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 48 h | 72 h | 96 h | 48 h | 72 h | 96 h | |

| TP-B01 | 35.7 bc | 49.1 d–f | 67.7 a | 1.73 ef ± 0.06 | 1.85 b–d ± 0.05 | 1.55 d ± 0.05 |

| TP-B02 | 33.3 cd | 53.2 b–d | 61.4 bc | 1.80 de ± 0.10 | 1.70 d–f ± 0.10 | 1.85 b ± 0.05 |

| TP-B03 | 19.7 ef | 39.2 g | 61.1 bc | 2.16 bc ± 0.06 | 2.21 a ± 0.08 | 1.85 bc ± 0.05 |

| TP-B05 | 12.9 g | 36.8 g | 55.2 d | 2.35 a ± 0.05 | 2.30 a ± 0.10 | 2.15 a ± 0.05 |

| TP-B08 | 44.4 a | 60.6 a | 66.7 a | 1.50 g ± 0.10 | 1.43 g ± 0.06 | 1.60 d ± 0.10 |

| TP-B09 | 44.4 a | 52.6 b–d | 68.0 a | 1.50 g ± 0.10 | 1.72 d–f ± 0.07 | 1.53 d ± 0.12 |

| TP-B10 | 20.9 ef | 46.4 ef | 62.5 b | 2.13 bc ± 0.06 | 1.95 bc ± 0.15 | 1.80 c ± 0.10 |

| TP-B12 | 29.6 d | 51.1 cd | 62.5 b | 1.90 d ± 0.10 | 1.77 de ± 0.11 | 1.80 c ± 0.10 |

| TP-G13 | 22.2 e | 56.3 ab | 59.3 c | 2.10 c ± 0.10 | 1.59 f ± 0.08 | 1.95 b ± 0.05 |

| TP-G14 | 38.8 b | 50.5 c–e | 63.5 b | 1.65 f ± 0.05 | 1.80 c–e ± 0.10 | 1.75 c ± 0.05 |

| TP-G18 | 32.0 cd | 50.5 c–e | 62.5 b | 1.83 de ± 0.12 | 1.80 c–e ± 0.10 | 1.80 c ± 0.10 |

| TP-G19 | 16.6 fg | 45.0 f | 63.9 b | 2.25 ab ± 0.05 | 2.00 b ± 0.10 | 1.73 c ± 0.06 |

| TP-C24 | 32.0 cd | 56.0 b | 61.8 bc | 1.83 de ± 0.06 | 1.60 f ± 0.10 | 1.83 bc ± 0.06 |

| TP-C25 | 33.3 cd | 55.1 bc | 68.7 a | 1.80 de ± 0.10 | 1.63 ef ± 0.06 | 1.50 d ± 0.10 |

| F | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| CV (%) | 55.7 | 36.2 | 20.4 | 6.08 | 7.05 | 5.83 |

| Fungal Strain | Antagonistic Efficiency (%) | Diameter of Pseudopestalotiopsis chinensis PCP-B02-B2 (cm) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 48 h | 72 h | 96 h | 48 h | 72 h | 96 h | |

| TP-B01 | 19.9 f | 38.6 g | 64.2 b | 2.05 a ± 0.05 | 2.0 b ± 0.10 | 1.30 f ± 0.10 |

| TP-B02 | 42.7 b–d | 52.4 b–d | 54.6 d | 1.46 cef ± 0.06 | 1.55 e–g ± 0.05 | 1.65 d ± 0.05 |

| TP-B03 | 37.5 de | 54.0 b | 53.2 d | 1.60 bc ± 0.10 | 1.50 g ± 0.10 | 1.70 cd ± 0.10 |

| TP-B05 | 18.0 f | 24.8 h | 40.9 f | 2.10 a ± 0.10 | 2.45 a ± 0.05 | 2.15 a ± 0.05 |

| TP-B08 | 49.2 a | 55.0 b | 71.1 a | 1.30 f ± 0.10 | 1.46 g ± 0.06 | 1.05 g ± 0.05 |

| TP-B09 | 33.6 e | 47.8 d–f | 66.1 b | 1.70 b ± 0.10 | 1.70 c–e ± 0.10 | 1.23 f ± 0.06 |

| TP-B10 | 45.3 ab | 48.9 c–f | 64.2 b | 1.40 ef ± 0.10 | 1.66 c–f ± 0.06 | 1.30 f ± 0.10 |

| TP-B12 | 43.3 bc | 46.3 ef | 58.7 c | 1.45 de ± 0.05 | 1.75 cd ± 0.05 | 1.50 e ± 0.10 |

| TP-G13 | 16.0 f | 35.6 g | 42.3 f | 2.15 a ± 0.05 | 2.10 b ± 0.10 | 2.10 a ± 0.10 |

| TP-G14 | 43.3 bc | 63.2 a | 67.0 b | 1.45 de ± 0.05 | 1.20 h ± 0.10 | 1.20 f ± 0.10 |

| TP-G18 | 38.3 c–e | 44.8 f | 49.1 e | 1.57 b–d ± 0.04 | 1.80 c ± 0.10 | 1.85 b ± 0.05 |

| TP-G19 | 41.4 b–d | 50.2 b–e | 60.1 c | 1.50 cef ± 0.10 | 1.62 d–g ± 0.07 | 1.45 e ± 0.05 |

| TP-C24 | 46.6 ab | 50.9 b–e | 49.6 e | 1.36 ef ± 0.06 | 1.60 d–g ± 0.10 | 1.83 bc ± 0.06 |

| TP-C25 | 35.5 e | 52.9 bc | 64.2 b | 1.65 b ± 0.05 | 1.53 fg ± 0.12 | 1.30 f ± 0.10 |

| F | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| CV (%) | 49.0 | 38.1 | 28.8 | 6.08 | 6.40 | 6.23 |

| Fungal Strain | Antagonistic Efficiency (%) | Diameter of Pseudopestalotiopsis camelliae-sinensis PCP-B03-A1 (cm) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 48 h | 72 h | 96 h | 48 h | 72 h | 96 h | |

| TP-B01 | 28.0 bc | 50.6 a | 57.4 a | 1.90 de ± 0.10 | 1.50 f ± 0.10 | 1.63 e ± 0.06 |

| TP-B02 | 19.2 de | 24.3 f | 47.9 b | 2.13 bc ± 0.06 | 2.30 a ± 0.10 | 2.00 d ± 0.10 |

| TP-B03 | 18.6 de | 38.2 bc | 42.7 c | 2.15 bc ± 0.05 | 1.87 de ± 0.07 | 2.20 c ± 0.10 |

| TP-B05 | 24.2 cd | 32.5 c–e | 34.9 e | 2.00 cd ± 0.10 | 2.05 b–d ± 0.05 | 2.50 a ± 0.10 |

| TP-B08 | 17.9 e | 41.9 b | 56.5 a | 2.16 b ± 0.15 | 1.76 e ± 0.06 | 1.66 e ± 0.06 |

| TP-B09 | 26.1 bc | 43.0 b | 55.7 a | 1.95 de ± 0.05 | 1.76 e ± 0.15 | 170 e ± 0.10 |

| TP-B10 | 31.8 ab | 27.6 ef | 40.1 cd | 1.80 ef ± 0.10 | 2.20 ab ± 0.10 | 2.30 bc ± 0.10 |

| TP-B12 | 11.0 f | 24.3 f | 37.5 de | 2.35 a ± 0.05 | 2.30 a ± 0.10 | 2.40 ab ± 0.10 |

| TP-G13 | 30.5 ab | 29.2 d–f | 34.9 e | 1.83 ef ± 0.06 | 2.15 a–c ± 0.05 | 2.50 a ± 0.10 |

| TP-G14 | 26.1 bc | 27.6 ef | 39.2 cd | 1.95 de ± 0.05 | 2.20 ab ± 0.10 | 2.33 bc ± 0.06 |

| TP-G18 | 31.8 ab | 34.2 cd | 49.9 b | 1.80 ef ± 0.10 | 2.0 cd ± 0.10 | 1.92 d ± 0.07 |

| TP-G19 | 16.7 e | 33.1 c–e | 40.1 cd | 2.20 b ± 0.10 | 2.03 b–d ± 0.12 | 2.30 bc ± 0.10 |

| TP-C24 | 35.6 a | 30.9 de | 40.1 cd | 1.70 f ± 0.10 | 2.10 bc ± 0.10 | 2.30 bc ± 0.10 |

| TP-C25 | 35.6 a | 40.8 b | 56.5 a | 1.70 f ± 0.10 | 1.80 e ± 0.10 | 1.66 e ± 0.06 |

| F | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| CV (%) | 66.9 | 54.2 | 34.1 | 6.37 | 6.71 | 6.17 |

| Strains | Chitinase | Endo-β-1,3-Glucanase | Exo-β-1,3 Glucanase |

|---|---|---|---|

| (UI mL−1) | |||

| TP-B01 | 0.301 a | 0.064 a | 0.020 a |

| TP-B08 | 0.217 c | 0.032 c | 0.007 c |

| TP-B09 | 0.251 b | 0.049 b | 0.017 b |

| TP-B25 | 0.223 c | 0.019 d | 0.007 c |

| F | * | * | * |

| CV (%) | 4.10 | 13.3 | 8.60 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Khuong, N.Q.; Duy, L.B.; Thuan, V.M.; Ngan, N.T.; Hiep, P.C.; Quang, L.T.; Trong, N.D.; Thu, H.N.; Xuan, D.T.; Thu, L.T.M.; et al. Application of Trichoderma spp. to Control Colletotrichum sp. and Pseudopestalotiopsis spp., Causing Agents of Fruit Rot in Pomelo (Citrus maxima (Burm.) Merr.). Appl. Microbiol. 2025, 5, 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/applmicrobiol5030066

Khuong NQ, Duy LB, Thuan VM, Ngan NT, Hiep PC, Quang LT, Trong ND, Thu HN, Xuan DT, Thu LTM, et al. Application of Trichoderma spp. to Control Colletotrichum sp. and Pseudopestalotiopsis spp., Causing Agents of Fruit Rot in Pomelo (Citrus maxima (Burm.) Merr.). Applied Microbiology. 2025; 5(3):66. https://doi.org/10.3390/applmicrobiol5030066

Chicago/Turabian StyleKhuong, Nguyen Quoc, Le Ba Duy, Vo Minh Thuan, Nguyen Thanh Ngan, Phan Chan Hiep, Le Thanh Quang, Nguyen Duc Trong, Ha Ngoc Thu, Do Thi Xuan, Le Thi My Thu, and et al. 2025. "Application of Trichoderma spp. to Control Colletotrichum sp. and Pseudopestalotiopsis spp., Causing Agents of Fruit Rot in Pomelo (Citrus maxima (Burm.) Merr.)" Applied Microbiology 5, no. 3: 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/applmicrobiol5030066

APA StyleKhuong, N. Q., Duy, L. B., Thuan, V. M., Ngan, N. T., Hiep, P. C., Quang, L. T., Trong, N. D., Thu, H. N., Xuan, D. T., Thu, L. T. M., Nguyen, T. T. K., Xuan, L. N. T., & Phong, N. T. (2025). Application of Trichoderma spp. to Control Colletotrichum sp. and Pseudopestalotiopsis spp., Causing Agents of Fruit Rot in Pomelo (Citrus maxima (Burm.) Merr.). Applied Microbiology, 5(3), 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/applmicrobiol5030066