Exploring Phenological and Agronomic Parameters of Greek Lentil Landraces for Developing Climate-Resilient Cultivars Adapted to Mediterranean Conditions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material

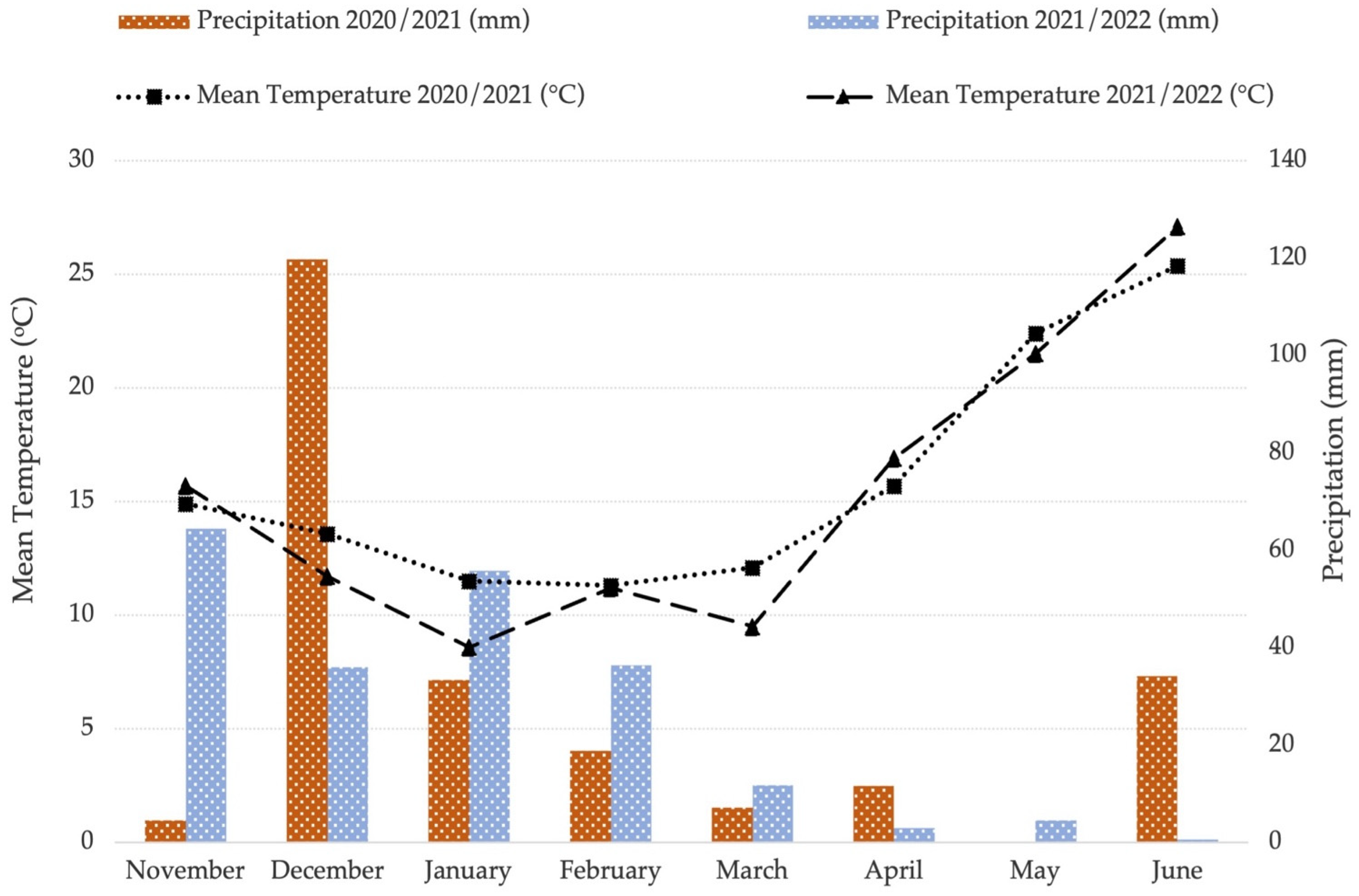

2.2. Study Location, Experimental Design, and Crop Management

2.3. Sampling, Measurements, and Methods

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Phenological Parameters

3.2. Plant Population and Yield Performance

3.3. Yield-Related Parameters

3.4. Seed Physical and Quality Parameters

3.5. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) of Evaluated Parameters

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BY | Biological yield |

| HI | Harvest index |

| LAP | Leaf area per plant |

| NP | Number of plants at harvest |

| NBP | Number of branches per plant |

| NPP | Number of pods per plant |

| NSP | Number of seeds per pod |

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

| PH | Plant height |

| SD | Seed diameter |

| SY | Seed yield |

| SYL | Seed yield loss |

| SYP | Seed yield per plant |

| SPC | Seed protein content |

| SYLP | Seed yield loss percentage |

| TF | Time to flowering |

| TM | Time to maturity |

| TSW | Thousand seed weight |

References

- Scippa, G.S.; Trupiano, D.; Rocco, M.; Viscosi, V.; Di Michele, M.; D’Andrea, A.; Chiatante, D. An Integrated Approach to the Characterization of Two Autochthonous Lentil (Lens culinaris) Landraces of Molise (South-Central Italy). Heredity 2008, 101, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonnante, G.; Hammer, K.; Pignone, D. From the Cradle of Agriculture, a Handful of Lentils: History of Domestication. Rend. Lincei 2009, 20, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ates, D. Genetic Diversity in Lentil Landraces Revealed by Diversity Array Technology (DArT). Turk. J. Field Crops 2019, 24, 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochfort, S.; Panozzo, J. Phytochemicals for health, the role of pulses. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 7981–7994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaale, L.D.; Siddiq, M.; Hooper, S. Lentil (Lens culinaris Medik.) as Nutrient-Rich and Versatile Food Legume: A Review. Legume Sci. 2023, 5, e169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.A.; Iqbal, M.S.; Akbar, M.; Arshad, N.; Munir, S.; Ali, M.A.; Massod, H.; Ahmad, T.; Shaheen, N.; Tahir, A.; et al. Estimating Genetic Variability among Diverse Lentil Collections through Novel Multivariate Techniques. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0269177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montejano-Ramírez, V.; Valencia-Cantero, E. The Importance of Lentils: An Overview. Agriculture 2024, 14, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudryj, A.N.; Yu, N.; Aukema, H.M. Nutritional and health benefits of pulses. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2014, 39, 1197–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAOSTAT. Statistics Division, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QI (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Liber, M.; Duarte, I.; Maia, A.T.; Oliveira, H.R. The History of Lentil (Lens culinaris subsp. culinaris) Domestication and Spread as Revealed by Genotyping-by-Sequencing of Wild and Landrace Accessions. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 628439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preiti, G.; Calvi, A.; Badagliacca, G.; Lo Presti, E.; Monti, M.; Bacchi, M. Agronomic Performances and Seed Yield Components of Lentil (Lens culinaris Medikus) Germplasm in a Semi-Arid Environment. Agronomy 2024, 14, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, H.; Vasconcelos, M.; Gil, A.M.; Pinto, E. Benefits of Pulse Consumption on Metabolism and Health: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 61, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghababaei, F.; McClements, D.J.; Pignitter, M.; Hadidi, M. A Comprehensive Review of Processing, Functionality, And Potential Applications of Lentil Proteins in the Food Industry. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2024, 333, 103280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatty, R.S. Composition and Quality of Lentil (Lens culinaris Medik.): A Review. Can. Inst. Food Sci. Technol. J. 1988, 21, 144–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khazaei, H.; Subedi, M.; Nickerson, M.; Martínez-Villaluenga, C.; Frias, J.; Vandenberg, A. Seed Protein of Lentils: Current Status, Progress, and Food Applications. Foods 2019, 8, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Etemadi, F.; Franck, W.; Franck, S.; Abdelhamid, M.T.; Ahmadi, J.; Mohammed, Y.A.; Lamb, P.; Miller, J.; Carr, P.M.; et al. Evaluation of Environment and Cultivar Impact on Lentil Protein, Starch, Mineral Nutrients, and Yield. Crop Sci. 2022, 62, 893–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, O.A.M.; Moreno, R.R.; Camara, M.F. Mineral and Trace Element Content in Legumes (Lentils, Chickpeas and Beans): Bioaccessibility and Probabilistic Assessment of the Dietary Intake. J. Food Comp. Anal. 2018, 73, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Arntfield, S.D.; Nickerson, M. Changes in Levels of Phytic Acid, Lectins and Oxalates during Soaking and Cooking of Canadian Pulses. Food Res. Int. 2018, 107, 660–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Canqui, H.; Holman, J.D.; Schlegel, A.J.; Tatarko, J.; Shaver, T.M. Replacing Fallow with Cover Crops in a Semiarid Soil: Effects on Soil Properties. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2013, 77, 1026–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, Y.; Hamel, C.; Kutcher, H.R.; Poppy, L. Lentil Enhances Agroecosystem Productivity with Increased Residual Soil Water and Nitrogen. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2017, 32, 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesfin, S.; Gebresamuel, G.; Haile, M.; Zenebe, A. Potentials of Legumes Rotation on Yield and Nitrogen Uptake of Subsequent Wheat Crop in Northern Ethiopia. Heliyon 2023, 9, e16126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgopoulou, E.; Gakis, N.; Kapetanakis, D.; Voloudakis, D.; Markaki, M.; Sarafidis, Y.; Lalas, D.P.; Laliotis, G.P.; Akamati, K.; Bizelis, I.; et al. Climate Change Risks for the Mediterranean Agri-Food Sector: The Case of Greece. Agriculture 2024, 14, 770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxevanos, D.; Kargiotidou, A.; Noulas, C.; Kouderi, A.-M.; Aggelakoudi, M.; Petsoulas, C.; Tigka, E.; Mavromatis, A.; Tokatlidis, I.; Beslemes, D.; et al. Lentil Cultivar Evaluation in Diverse Organic Mediterranean Environments. Agronomy 2024, 14, 790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor, M.M.A.; Tahjib-Ul-Arif, M.; Alim, S.M.A.; Islam, M.M.; Hasan, M.T.; Babar, M.A.; Hossain, M.A.; Jewel, Z.A.; Murata, Y.; Mostofa, M.G. Lentil Adaptation to Drought Stress: Response, Tolerance, and Breeding Approaches. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1403922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sehgal, A.; Sita, K.; Rehman, A.; Farooq, M.; Kumar, S.; Yadav, R.; Nayyar, H.; Singh, S.; Siddique, K.H.M. Chapter 13—Lentil. In Crop Physiology Case Histories for Major Crops; Sadras, V.O., Calderini, D.F., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; pp. 408–428. [Google Scholar]

- Lazaro, A.; Ruiz, M.; de la Rosa, L.; Martin, I. Relationship between Agro/Morphological Characters and Climatic Parameters in Spanish Landraces of Lentil (Lens culinaris Medik.). Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2001, 48, 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toklu, F.; Karakoy, T.; Haklı, E.; Bicer, T.; Brandolini, A.; Kilian, B.; Ozkan, H. Genetic Variation among Lentil (Lens culinaris Medik.) Landraces from Southeast Turkey. Plant Breed. 2009, 128, 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, S.A.; Sarıkaya, M.F.; Nadeem, M.A.; Ali, A.; Mortazavi, P.; Bedir, M.; Tatar, M.; Madenova, A.; Kabylbekova, B.; Ali, F.; et al. Revealing the Genetic Diversity and Population Structure in Lentil (Lens culinaris) Germplasm using Inter-Primer Binding Site (iPBS)-Retrotransposon Markers. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardi, M.; Materne, M.; Cogan, N.O.; Rodda, M.; Daetwyler, H.D.; Slater, A.T.; Forster, J.W.; Kaur, S. Assessment of Genetic Variation within a Global Collection of Lentil (Lens culinaris Medik.) Cultivars and Landraces using SNP Markers. BMC Genet. 2014, 15, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suri, G.K.; Braich, S.; Noy, D.M.; Rosewarne, G.M.; Cogan, N.O.I.; Kaur, S. Advances in lentil production through heterosis: Evaluating generations and breeding systems. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0262857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Union for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants (UPOV). Lentil: Guidelines for the Conduct of Tests for Distinctness, Uniformity and Stability, 2015. Available online: https://www.upov.int/edocs/tgdocs/en/tg210.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- IUSS Working Group WRB. World Reference Base for Soil Resources. In International Soil Classification System for Naming Soils and Creating Legends for Soil Maps, 4th ed.; International Union of Soil Sciences (IUSS): Vienna, Austria, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- AGPG. Lentil Descriptor; International Board for Plant Genetic Resources: Rome, Italy, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Plaza, J.; Morales-Corts, M.R.; Pérez-Sánchez, R.; Revilla, I.; Vivar-Quintana, A.M. Morphometric and Nutritional Characterization of the Main Spanish Lentil Cultivars. Agriculture 2021, 11, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Nahas, A.I.; El-Shazly, H.H.; Ahmed, S.M.; Omran, A.A.A. Molecular and Biochemical Markers in Some Lentil (Lens culinaris Medik.) Genotypes. Ann. Agric. Sci. 2011, 56, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardar, M.M.; Tahir, A.T.; Ali, S.; Ayub, J.; Ali, J.; Kausar, F.; Yasmin, T.; Jabeen, Z.; Ilyas, M.K. Insights from Lentil Germplasm Resources Leading to Crop Improvement Under Changing Climatic Conditions. Life 2025, 15, 561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, J.; Sen Gupta, D.; Baum, M.; Varshney, R.K.; Kumar, S. Genomics-Assisted Lentil Breeding: Current Status and Future Strategies. Legum. Sci. 2021, 3, e71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Yadav, P.; Seema; Kumar, R.R.; Kushwaha, A.; Rashid, M.H.; Tarannum, N. Lentil Breeding: Present State and Future Prospects. Int. J. Environ. Clim. Chang. 2022, 12, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra-García, A.; Gioia, T.; von Wettberg, E.; Logozzo, G.; Papa, R.; Bitocchi, E.; Bett, K.E. Intelligent Characterization of Lentil Genetic Resources: Evolutionary History, Genetic Diversity of Germplasm, and the Need for Well-Represented Collections. Curr. Protoc. 2021, 1, e134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idrissi, O.; Piergiovanni, A.R.; Toklu, F.; Houasli, C.; Udupa, S.M.; De Keyser, E.; Van Damme, P.; De Riek, J. Molecular Variance and Population Structure of Lentil (Lens culinaris Medik.) Landraces from Mediterranean Countries as Revealed by Simple Sequence Repeat DNA Markers: Implications for Conservation and Use. Plant Genet. Resour. Charact. Util. 2018, 16, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsanakas, G.F.; Mylona, P.V.; Koura, K.; Gleridou, A.; Polidoros, A.N. Genetic Diversity Analysis of the Greek Lentil (Lens culinaris) Landrace ‘Eglouvis’ Using Morphological and Molecular Markers. Plant Genet. Resour. Charact. Util. 2018, 16, 469–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghamdi, S.S.; Khan, A.M.; Ammar, M.H.; Harty, E.H.; Migdadi, H.M.; El-Khalik, S.M.; Al-Shameri, A.M.; Javed, M.M.; Al-Faifi, S.A. Phenological, Nutritional and Molecular Diversity Assessment among 35 Introduced Lentil (Lens culinaris Medik.) Genotypes Grown in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 277–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceritoglu, M.; Çığ, F.; Erman, M.; Ceritoglu, F. Integrating Multi-Trait Selection Indices for Climate-Resilient Lentils: A Three-Year Evaluation of Earliness and Yield Stability Under Semi-Arid Conditions. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Kumar, S.; Mehra, R.; Sood, S.; Malhotra, N.; Sinha, R.; Jamwal, S.; Gupta, V. Evaluation and Identification of Advanced Lentil Interspecific Derivatives Resulted in the Development of Early Maturing, High Yielding, and Disease-Resistant Cultivars Under Indian Agro-Ecological Conditions. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 936572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erskine, W.; Ellis, R.H.; Summerfield, R.J.; Roberts, E.H.; Hussain, A. Characterization of Responses to Temperature and Photoperiod for Time to Flowering in a World Lentil Collection. Theor. Appl. Genet. 1990, 80, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summerfield, R.J.; Roberts, E.H.; Erskine, W.; Ellis, R.H. Effects of Temperature and Photoperiod on Flowering in Lentil (Lens culinaris Medik.). Ann. Bot. 1985, 56, 659–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sita, K.; Sehgal, A.; HanumanthaRao, B.; Nair, R.M.; Vara Prasad, P.V.; Kumar, S.; Gaur, P.M.; Farooq, M.; Siddique, K.H.M.; Varshney, R.K.; et al. Food Legumes and Rising Temperatures: Effects, Adaptive Functional Mechanisms Specific to Reproductive Growth Stage and Strategies to Improve Heat Tolerance. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Barpete, S.; Kumar, J.; Gupta, P.; Sarker, A. Global Lentil Production: Constraints and Strategies. SATSA Mukhapatra-Annu. Tech. 2013, 17, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Shavrukov, Y.; Kurishbayev, A.; Jatayev, S.; Shvidchenko, V.; Zotova, L.; Koekemoer, F.; De Groot, S.; Soole, K.; Langridge, P. Early Flowering as a Drought Escape Mechanism in Plants: How Can It Aid Wheat Production? Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choukri, H.; El Haddad, N.; Aloui, K.; Hejjaoui, K.; El-Baouchi, A.; Smouni, A.; Thavarajah, D.; Maalouf, F.; Kumar, S. Effect of High Temperature Stress During the Reproductive Stage on Grain Yield and Nutritional Quality of Lentil (Lens culinaris Medikus). Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 857469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suárez, J.C.; Urban, M.O.; Contreras, A.T.; Noriega, J.E.; Deva, C.; Beebe, S.E.; Polanía, J.A.; Casanoves, F.; Rao, I.M. Water Use, Leaf Cooling and Carbon Assimilation Efficiency of Heat-Resistant Common Beans Evaluated in Western Amazonia. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 644010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awasthi, R.; Kaushal, N.; Vadez, V.; Turner, N.C.; Berger, J.; Siddique, K.H.M.; Nayyar, H. Individual and Combined Effects of Transient Drought and Heat Stress on Carbon Assimilation and Seed Filling in Chickpea. Funct. Plant Biol. 2014, 41, 1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, M.H.; Al-Khaishany, M.Y.; Al-Qutami, M.A.; Al-Whaibi, M.H.; Grover, A.; Ali, H.M.; Al-Wahibi, M.S. Morphological and Physiological Characterization of Different Genotypes of Faba Bean Under Heat Stress. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2015, 22, 656–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parihar, A.K.; Tripathi, S.; Hazra, K.K.; Lamichaney, A.; Gupta, D.S.; Kumar, J.; Singh, A.K.; Sharma, J.D.; Sofi, P.A.; Lone, A.A.; et al. Environmental Adaptation of Small-Seeded Lentils (Lens culinaris) in Indian Climates: Insights into Crop–Environment Interactions, Mega-Environments, and Breeding Approaches. Crop Sci. 2025, 65, e70090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ninou, E.; Papathanasiou, F.; Vlachostergios, D.N.; Mylonas, I.; Kargiotidou, A.; Pankou, C.; Papadopoulos, I.; Sinapidou, E.; Tokatlidis, I. Intense Breeding within Lentil Landraces for High-Yielding Pure Lines Sustained the Seed Quality Characteristics. Agriculture 2019, 9, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erskine, W. Selection for Pod Retention and Pod Indehiscence in Lentils. Euphytica 1985, 34, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ćeran, M.; Miladinović, D.; Đorđević, V.; Trkulja, D.; Radanović, A.; Glogovac, S.; Kondić-Špika, A. Genomics-Assisted Speed Breeding for Crop Improvement: Present and Future. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 8, 1383302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choukri, H.; Aloui, K.; El Haddad, N.; Hejjaoui, K.; Smouni, A.; Kumar, S. Variation of Seed Yield and Nutritional Quality Traits of Lentil (Lens culinaris Medikus) Under Heat and Combined Heat and Drought Stresses. Plants 2025, 14, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takele, E.; Mekbib, F.; Mekonnen, F. Genetic Variability and Characters Association for Yield, Yield Attributing Traits and Protein Content of Lentil (Lens culinaris Medikus) Genotype in Ethiopia. CABI Agric. Biosci. 2022, 3, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karadavut, U. Path Analysis for Yield and Yield Components in Lentil (Lens culinaris Medik.). Turk. J. Field Crops 2009, 14, 97–104. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, A.; Gill, R.K.; Singh, M. Genetic Variability and Association Analysis for Various Agro Morphological Traits in Lentil (Lens culinaris M.). Legum. Res. 2020, 43, 776–779. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, P.; Vimal, S.C.; Kumar, A. Study of Simple Correlation Coefficients for Yield and Its Component Traits in Lentil (Lens culinaris Medik.). Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2017, 6, 3260–3265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Chaudhary, L.; Kumar, M.; Yadav, R.; Devi, U.; Amit; Kumar, V. Phenotypic Diversity Analysis of Lens culinaris Medik. Accessions for Selection of Superior Genotypes. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Aysh, F.M. Genetic Variability, Correlation and Path Coefficient Analysis of Yield and Some Yield Components in Landraces of Lentil (Lens culinaris Medik.). Jordan J. Agric. Sci. 2014, 10, 737–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.R.; Singh, S.; Gill, R.K.; Kumar, R.; Parihar, A.K. Selection of Promising Genotypes of Lentil (Lens culinaris Medik.) by Deciphering Genetic Diversity and Trait Association. Legum. Res. 2020, 43, 764–769. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, P.; Pandey, A. Correlation Between Different Traits of Aromatic Rice (Oryza sativa L.) and Their Cause-Effect Relationship. Appl. Biol. Res. 2012, 14, 47–53. [Google Scholar]

- Papastylianou, P.; Vlachostergios, D.N.; Dordas, C.; Tigka, E.; Papakaloudis, P.; Kargiotidou, A.; Pratsinakis, E.; Koskosidis, A.; Pankou, C.; Kousta, A.; et al. Genotype X Environment Interaction Analysis of Faba Bean (Vicia faba L.) for Biomass and Seed Yield across Different Environments. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Perez, V.; Shunmugam, A.S.K.; Rao, S.; Cossani, C.M.; Tefera, A.T.; Fitzgerald, G.J.; Armstrong, R.; Rosewarne, G.M. Breeding Has Selected for Architectural and Photosynthetic Traits in Lentils. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 925987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusmenoglu, I.; Muehlbauer, F.J. Genetic Variation for Biomass and Residue Production in Lentil (Lens culinaris Medik.). II. Factors Determining Seed and Straw Yield. Crop Sci. 1998, 38, 911–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, S.L.; Ceccarelli, S.; Blair, M.W.; Upadhyaya, H.D.; Are, A.K.; Ortiz, R. Landrace Germplasm for Improving Yield and Abiotic Stress Adaptation. Trends Plant Sci. 2016, 21, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, A.; Erskine, W. Recent Progress in the Ancient Lentil. J. Agric. Sci. 2006, 144, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Duan, R.; Long, J.; Bu, H. Seed Size-Number Trade-Off Exists in Graminoids but Not in Forbs or Legumes: A Study from 11 Common Species in Alpine Steppe Communities. Plants 2025, 14, 2730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Genotype | Accession Number | Landrace/Cultivar Name | Date of Collection | Collecting Institute | Region | Collecting Site | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ID | Genotype Class | Seed Size | ||||||

| DOM_Ldr | Landrace | Large Seed | - | - | 2017 | Laboratory of Agronomy, Agricultural University of Athens | Central Greece | Domokos, Fthiotis |

| LA2 large | Landrace | Large Seed | PI 297749 | ILL 281 | 12 May 1964 | Western Regional Plant Introduction Station, USDA-ARS | Thessaly | Larissa |

| APK_Ldr | Landrace | Small Seed | - | - | 2017 | Laboratory of Agronomy, Agricultural University of Athens | Peloponnese | Arkadia |

| BEL | Landrace | Small Seed | K-095/06 | - | 22 September 2006 | Institute of Plant Breeding and Genetic Resources, ELGO-Dimitra | Western Macedonia | Velanidia, Kozani |

| CHR | Landrace | Small Seed | LENS 65 | LENS 65 | 1942 | Leibniz Institute of Plant Genetic and Crop Plant Research | Peloponnese | Chrysovitsi, Arkadia |

| DIG | Landrace | Small Seed | IK-100/06 | - | 25 September 2006 | Institute of Plant Breeding and Genetic Resources, ELGO-Dimitra | Ionian Islands | Digaleto, Kefallinia |

| DIL | Landrace | Small Seed | GRC1766/04 | - | 8 August 2004 | Institute of Plant Breeding and Genetic Resources, ELGO-Dimitra | Thessaly | Dilofo, Larissa |

| EGL | Landrace | Small Seed | PI 633933 | G075 | 9 September 1999 | Western Regional Plant Introduction Station, USDA-ARS | Ionian Islands | Englouvi, Lefkada |

| EGL_Ldr | Landrace | Small Seed | - | - | 2019 | Laboratory of Agronomy, Agricultural University of Athens | Ionian Islands | Englouvi, Lefkada |

| GER | Landrace | Small Seed | HL-164/07 | - | 8 July 2007 | Institute of Plant Breeding and Genetic Resources, ELGO-Dimitra | Crete | Tzermiado, Lasithi |

| GYT | Landrace | Small Seed | LENS 47 | LENS 47 | 1942 | Leibniz Institute of Plant Genetic and Crop Plant Research | Peloponnese | Polovitsa, Lakonia |

| IER | Landrace | Small Seed | LENS 83 | LENS 83 | 1942 | Leibniz Institute of Plant Genetic and Crop Plant Research | Crete | Ierapetra, Lasithi |

| KOR | Landrace | Small Seed | PI 297765 | ILL 297 | 12 May 1964 | Western Regional Plant Introduction Station, USDA-ARS | Western Macedonia | Korynos, Kastoria |

| KOZ | Landrace | Small Seed | LENS 7 | LENS 7 | 1941 | Leibniz Institute of Plant Genetic and Crop Plant Research | Western Macedonia | Monastiraki, Kozani |

| LA1 | Landrace | Small Seed | PI 297739 | ILL 271 | 12 May 1964 | Western Regional Plant Introduction Station, USDA-ARS | Thessaly | Larissa |

| LAX | Landrace | Small Seed | F-173/06 | - | 4 October 2006 | Institute of Plant Breeding and Genetic Resources, ELGO-Dimitra | Western Macedonia | Lachanokipoi, Kastoria |

| MOL | Landrace | Small Seed | PI 297790 | ILL 322 | 12 May 1964 | Western Regional Plant Introduction Station, USDA-ARS | Ionian Islands | Molle, Kefallinia |

| MOL_Ldr | Landrace | Small Seed | - | - | 2017 | Laboratory of Agronomy, Agricultural University of Athens | Ionian Islands | Molle, Kefallinia |

| PRG | Landrace | Small Seed | PI 297789 | ILL 321 | 12 May 1964 | Western Regional Plant Introduction Station, USDA-ARS | Ionian Islands | Pyrgi, Kefallinia |

| PTO | Landrace | Small Seed | LENS 4 | LENS 4 | 1941 | Leibniz Institute of Plant Genetic and Crop Plant Research | Western Macedonia | Agricultural Experimental Station of Ptolemaida, Kozani |

| RIZ | Landrace | Small Seed | P-118/06 | - | 25 August 2006 | Institute of Plant Breeding and Genetic Resources, ELGO-Dimitra | Peloponnese | Riza, Lakonia |

| TSO | Landrace | Small Seed | K-106/06 | - | 23 September 2006 | Institute of Plant Breeding and Genetic Resources, ELGO-Dimitra | Western Macedonia | Tsotyli, Kastoria |

| ELPm | Cultivar | Large Seed | - | ELPIDA | 2019 | Institute of Industrial and Forage Crops, ELGO-Dimitra (commercial cultivar—registration date: 19 September 2016) | - | - |

| IKAm | Cultivar | Large Seed | - | IKARIA | 2019 | Institute of Industrial and Forage Crops, ELGO-Dimitra (commercial cultivar—registration date: 27 July 1990) | - | - |

| THEm | Cultivar | Large Seed | - | THESSALIA | 2019 | Institute of Industrial and Forage Crops, ELGO-Dimitra (commercial cultivar—registration date: 7 March 1986) | - | - |

| ARK | Cultivar | Small Seed | LENS 235 | ARCADIA | 1989 | Leibniz Institute of Plant Genetic and Crop Plant Research (Donor: Institute of Industrial and Forage Crops, ELGO-Dimitra) (commercial cultivar—registration date: 7 March 1986) | - | - |

| ARX | Cultivar | Small Seed | LENS 234 | ARACHOVA | 1989 | Leibniz Institute of Plant Genetic and Crop Plant Research (Donor: Institute of Industrial and Forage Crops, ELGO-Dimitra) (commercial cultivar—registration date: 7 March 1986) | - | - |

| ATHm | Cultivar | Small Seed | - | ATHENA | 2019 | Institute of Industrial and Forage Crops, ELGO-Dimitra (commercial cultivar—registration date: 29 December 2006) | - | - |

| DIMm | Cultivar | Small Seed | - | DIMITRA | 2019 | Institute of Industrial and Forage Crops, ELGO-Dimitra (commercial cultivar—registration date: 7 March 1986) | - | - |

| PEL | Cultivar | Small Seed | LENS 237 | PELASGIA | 1989 | Leibniz Institute of Plant Genetic and Crop Plant Research (Donor: Institute of Industrial and Forage Crops, ELGO-Dimitra) (commercial cultivar—registration date: 7 March 1986) | - | - |

| SAMm | Cultivar | Small Seed | - | SAMOS | 2019 | Institute of Industrial and Forage Crops, ELGO-Dimitra (commercial cultivar—registration date: 27 July 1990) | - | - |

| Genotype | Stem: Anthocyanin Coloration | Leaflet: Size | Leaflet: Shape | Flower: Color of Standard | Flower: Violet Stripes of Standard | Seed: Main Color | Seed: Pattern of Secondary Color * | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ID | Genotype Class | Seed Size | |||||||

| DOM_Ldr | L | LS | Present | Large | Elliptic | Pink-Blue | Present | Green-Pink | Absent |

| LA2 large | L | LS | Absent | Large | Elliptic | White | Present | Green-Pink | Absent |

| APK_Ldr | L | SS | Present | Medium | Elliptic | Pink-Blue | Present | Green-Pink | Absent + Blotched |

| BEL | L | SS | Present | Small | Elliptic | Pink-Blue | Present | Green-Pink | Absent |

| CHR | L | SS | Present | Medium | Elliptic | White | Present | Pink-Green | Absent |

| DIG | L | SS | Absent | Medium | Elliptic | Blue | Present | Pink-Green | Absent + Marbled |

| DIL | L | SS | Absent | Large | Elliptic | White | Present | Green | Absent |

| EGL | L | SS | Absent | Medium | Elliptic | White | Present | Green-Pink | Absent |

| EGL_Ldr | L | SS | Absent | Medium | Elliptic | White | Present | Green-Pink | Absent + Blotched + Marbled-Blotched |

| GER | L | SS | Present | Medium | Elliptic | White | Present | Green | Absent |

| GYT | L | SS | Absent | Large | Elliptic | Pink-Blue | Present | Green | Absent |

| IER | L | SS | Absent | Medium | Obovate | White | Present | Green | Absent + Blotched + Marbled-Blotched |

| KOR | L | SS | Absent | Small | Elliptic | Pink-Blue | Present | Green | Absent |

| KOZ | L | SS | Present | Small | Elliptic | Pink-Blue | Present | Green | Absent |

| LA1 | L | SS | Absent | Medium | Elliptic | White | Absent | Greenish Yellow | Absent |

| LAX | L | SS | Absent | Small | Elliptic | Pink-Blue | Present | Pink-Green | Absent + Blotched |

| MOL | L | SS | Present | Medium | Elliptic | Pink-Blue | Present | Pink-Green | Absent + Blotched |

| MOL_Ldr | L | SS | Absent | Medium | Elliptic | Blue-Pink | Present | Pink-Green | Absent + Blotched |

| PRG | L | SS | Absent | Medium | Elliptic | White | Present | Pink-Green | Absent |

| PTO | L | SS | Absent | Medium | Obovate | White | Present | Green | Absent |

| RIZ | L | SS | Absent | Small | Obovate | Pink-Blue | Present | Green | Absent + Blotched + Spotted + Marbled |

| TSO | L | SS | Present | Medium | Obovate | Pink-Blue | Present | Pink-Green | Absent |

| ELPm | C | LS | Absent | Medium–Large | Elliptic | White | Present | Green | Absent |

| IKAm | C | LS | Absent | Large | Elliptic | White | Present | Green | Absent |

| THEm | C | LS | Absent | Medium–Large | Elliptic | White | Present | Pink-Green | Absent |

| ARK | C | SS | Absent | Medium | Elliptic | White | Present | Green | Absent |

| ARX | C | SS | Absent | Medium | Elliptic | Pink-Blue | Present | Pink-Green | Absent |

| ATHm | C | SS | Absent | Medium | Elliptic | Pink-Blue | Present | Green | Absent |

| DIMm | C | SS | Absent | Medium | Elliptic | White | Present | Pink-Green | Absent |

| PEL | C | SS | Absent | Medium | Elliptic | White | Absent | Green-Pink | Absent |

| SAMm | C | SS | Present | Medium | Elliptic | White | Present | Green | Absent |

| Time to Flowering (TF; Days After Sowing to Flowering) | Time to Maturity (TM; Days After Sowing to Maturity) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | ||||

| 2020/2021 | 146.9 ± 2.0 b | 193.5 ± 0.5 b | ||

| 2021/2022 | 159.7 ± 1.5 a | 208.0 ± 0.6 a | ||

| Genotype | ||||

| ID | Genotype Class | Seed Size | ||

| DOM_Ldr | L | LS | 158.8 ± 2.6 bcdef | 202.0 ± 1.8 cdefg |

| LA2 large | L | LS | 156.8 ± 2.6 efg | 201.8 ± 2.7 cdefg |

| APK_Ldr | L | SS | 158.7 ± 3.0 bcdef | 203.0 ± 3.6 bcde |

| BEL | L | SS | 155.7 ± 3.7 fg | 196.5 ± 4.7 h |

| CHR | L | SS | 178.3 ± 0.9 a | 211.7 ± 1.7 a |

| DIG | L | SS | 155.2 ± 3.2 fgh | 204.0 ± 4.0 bcd |

| DIL | L | SS | 159.7 ± 1.1 bcdef | 205.6 ± 3.6 bc |

| EGL | L | SS | 159.3 ± 2.8 bcdef | 202.7 ± 2.6 bcdef |

| EGL_Ldr | L | SS | 158.3 ± 2.3 cdefg | 202.7 ± 4.8 bcdef |

| GER | L | SS | 156.2 ± 3.1 fg | 198.5 ± 5.6 gh |

| GYT | L | SS | 150.2 ± 3.4 hij | 192.3 ± 2.2 ij |

| IER | L | SS | 157.7 ± 2.8 efg | 199.7 ± 3.2 efgh |

| KOR | L | SS | 155.0 ± 3.6 fgh | 201.7 ± 5.1 defg |

| KOZ | L | SS | 159.8 ± 2.2 bcdef | 201.7 ± 5.1 defg |

| LA1 | L | SS | 163.8 ± 2.0 b | 204.5 ± 2.9 bcd |

| LAX | L | SS | 153.2 ± 2.4 ghi | 196.5 ± 4.7 h |

| MOL | L | SS | 163.0 ± 1.5 bcd | 202.0 ± 1.8 cdefg |

| MOL_Ldr | L | SS | 155.8 ± 3.2 fg | 197.5 ± 2.9 h |

| PRG | L | SS | 155.0 ± 3.1 fgh | 196.7 ±2.3 h |

| PTO | L | SS | 157.0 ± 3.5 efg | 202.3 ± 3.9 bcdef |

| RIZ | L | SS | 156.2 ± 3.0 fg | 199.0 ± 1.4 fgh |

| TSO | L | SS | 157.8 ± 2.7 defg | 202.0 ± 1.8 cdefg |

| ELPm | C | LS | 94.2 ± 7.3 k | 191.8 ± 2.3 j |

| IKAm | C | LS | 156.5 ± 3.2 efg | 205.5 ± 3.7 bcd |

| THEm | C | LS | 154.8 ± 3.2 fgh | 206.0 ± 3.6 b |

| ARK | C | SS | 148.8 ± 4.7 ij | 196.5 ± 4.7 h |

| ARX | C | SS | 163.5 ± 1.6 bc | 204.5 ± 2.9 bcd |

| ATHm | C | SS | 147.2 ± 4.9 j | 196.0 ± 4.5 hi |

| DIMm | C | SS | 156.8 ± 3.1 efg | 203.3 ± 4.4 bcde |

| PEL | C | SS | 162.0 ± 1.8 bcde | 204.0 ± 3.1 bcd |

| SAMm | C | SS | 91.2 ± 5.5 k | 191.8 ± 2.3 j |

| Source of Variance | df | |||

| FYear | 1 | 1406.837 *** | 3540.654 *** | |

| FGenotype | 30 | 314.398 *** | 44.489 *** | |

| FYear × Genotype | 30 | 8.799 *** | 17.771 *** | |

| Genotype Class | ||||

| L | 158.1 ± 0.7 a | 201.1 ± 0.8 a | ||

| C | 141.5 ± 3.9 b | 200.0 ± 1.3 a | ||

| Source of Variance | df | |||

| FYear | 1 | 32.335 *** | 282.214 *** | |

| FGenotype Class | 1 | 44.102 *** | 2.038 ns | |

| FYear × Genotype Class | 1 | 1.642 ns | 0.775 ns | |

| Seed Size | ||||

| LS | 144.0 ± 5.1 b | 201.5 ± 1.6 a | ||

| SS | 155.0 ± 1.2 a | 200.6 ± 0.7 a | ||

| Source of Variance | df | |||

| FYear | 1 | 18.209 *** | 152.71 *** | |

| FSeed Size | 1 | 11.057 ** | 0.405 ns | |

| FYear × Seed Size | 1 | 0.479 ns | 1.325 ns | |

| TF | TM | NP | SY | SYLP | SYL | BY | HI | PH | NBP | LAP | NPP | NSP | SYP | TSW | SD | SPC | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype | |||||||||||||||||||

| ID | Genotype Class | Seed Size | |||||||||||||||||

| DOM_Ldr | L | LS | 4.0 | 2.2 | 23.2 | 58.8 | 46.3 | 61.2 | 43.5 | 41.0 | 31.9 | 68.6 | 26.7 | 54.1 | 9.0 | 58.7 | 9.1 | 15.4 | 0.8 |

| LA2 large | L | LS | 4.1 | 3.3 | 36.8 | 56.8 | 97.5 | 45.2 | 46.2 | 45.5 | 24.5 | 38.2 | 23.7 | 50.6 | 18.6 | 56.9 | 5.2 | 5.7 | 1.3 |

| APK_Ldr | L | SS | 4.7 | 4.3 | 11.0 | 57.2 | 159.7 | 63.7 | 20.4 | 48.8 | 14.0 | 16.0 | 17.4 | 48.2 | 7.2 | 57.1 | 7.9 | 30.6 | 1.5 |

| BEL | L | SS | 5.9 | 5.9 | 10.1 | 57.2 | 57.6 | 60.6 | 30.2 | 31.7 | 13.4 | 24.3 | 29.8 | 51.8 | 8.6 | 57.3 | 11.9 | 3.4 | 3.2 |

| CHR | L | SS | 1.1 | 2.0 | 25.0 | 85.2 | 78.4 | 26.8 | 27.2 | 76.9 | 25.2 | 38.9 | 24.4 | 55.1 | 41.1 | 85.0 | 9.2 | 27.1 | 1.0 |

| DIG | L | SS | 5.0 | 4.8 | 17.4 | 58.7 | 63.1 | 90.5 | 69.2 | 15.3 | 19.1 | 39.5 | 21.5 | 64.9 | 3.6 | 58.6 | 11.2 | 3.2 | 2.4 |

| DIL | L | SS | 1.7 | 4.0 | 20.0 | 74.9 | 79.8 | 120.9 | 58.9 | 37.4 | 12.9 | 24.9 | 36.2 | 63.7 | 7.3 | 74.8 | 11.5 | 2.8 | 1.4 |

| EGL | L | SS | 4.3 | 3.1 | 12.1 | 41.7 | 49.7 | 39.4 | 23.1 | 26.2 | 19.0 | 23.8 | 23.1 | 39.3 | 8.4 | 41.6 | 6.3 | 4.5 | 0.6 |

| EGL_Ldr | L | SS | 3.5 | 5.8 | 13.3 | 36.1 | 29.0 | 30.4 | 18.9 | 27.4 | 21.9 | 21.8 | 15.6 | 36.1 | 4.3 | 36.2 | 6.7 | 4.8 | 3.5 |

| GER | L | SS | 4.9 | 6.9 | 12.5 | 62.8 | 89.1 | 57.1 | 25.9 | 68.4 | 17.2 | 20.7 | 23.6 | 51.5 | 9.7 | 62.7 | 11.0 | 3.0 | 4.0 |

| GYT | L | SS | 5.6 | 2.8 | 22.7 | 52.7 | 59.0 | 74.4 | 48.6 | 58.7 | 9.6 | 9.4 | 27.2 | 52.8 | 8.8 | 52.8 | 13.0 | 5.5 | 1.6 |

| IER | L | SS | 4.3 | 3.9 | 19.9 | 56.6 | 49.6 | 59.4 | 23.6 | 79.2 | 11.6 | 23.2 | 16.0 | 58.7 | 9.2 | 56.5 | 22.2 | 8.7 | 1.7 |

| KOR | L | SS | 5.7 | 6.2 | 11.4 | 60.2 | 75.1 | 91.0 | 32.3 | 58.0 | 25.7 | 24.3 | 15.0 | 54.4 | 13.9 | 60.3 | 11.7 | 16.8 | 3.8 |

| KOZ | L | SS | 3.3 | 6.2 | 20.7 | 31.8 | 78.0 | 84.6 | 36.8 | 16.2 | 23.7 | 33.3 | 21.6 | 29.5 | 4.4 | 31.6 | 7.2 | 2.5 | 3.6 |

| LA1 | L | SS | 3.0 | 3.5 | 41.0 | 79.1 | 62.3 | 99.6 | 35.1 | 83.8 | 16.1 | 52.5 | 22.7 | 67.2 | 21.3 | 79.2 | 13.9 | 8.2 | 0.9 |

| LAX | L | SS | 3.8 | 5.9 | 12.2 | 15.2 | 37.9 | 47.7 | 15.5 | 16.9 | 16.4 | 9.6 | 20.0 | 11.2 | 5.7 | 15.3 | 7.1 | 3.5 | 2.8 |

| MOL | L | SS | 2.3 | 2.2 | 17.0 | 57.0 | 41.2 | 65.2 | 43.5 | 36.5 | 20.0 | 35.0 | 13.0 | 54.1 | 7.9 | 57.1 | 16.5 | 4.1 | 0.7 |

| MOL_Ldr | L | SS | 5.0 | 3.6 | 40.9 | 46.6 | 73.4 | 94.4 | 36.5 | 22.3 | 10.9 | 42.4 | 19.6 | 50.8 | 4.7 | 46.7 | 12.1 | 3.8 | 0.9 |

| PRG | L | SS | 5.0 | 2.8 | 35.2 | 80.6 | 71.3 | 117.4 | 53.7 | 33.9 | 6.1 | 41.2 | 24.7 | 77.1 | 10.2 | 80.8 | 12.6 | 1.9 | 2.1 |

| PTO | L | SS | 5.5 | 4.7 | 17.7 | 47.7 | 48.9 | 47.9 | 22.9 | 43.9 | 14.6 | 16.8 | 16.7 | 38.2 | 7.7 | 47.6 | 12.2 | 5.9 | 2.3 |

| RIZ | L | SS | 4.7 | 1.7 | 24.8 | 31.0 | 32.7 | 40.2 | 34.5 | 13.9 | 24.9 | 16.2 | 17.8 | 34.3 | 10.3 | 31.1 | 12.0 | 4.5 | 2.8 |

| TSO | L | SS | 4.1 | 2.2 | 14.1 | 34.3 | 53.4 | 63.7 | 24.5 | 19.2 | 20.0 | 19.3 | 21.7 | 32.3 | 3.1 | 34.4 | 6.6 | 3.3 | 0.9 |

| ELPm | C | LS | 19.0 | 3.0 | 60.5 | 114.6 | 103.4 | 64.1 | 61.0 | 68.0 | 14.8 | 28.9 | 20.0 | 114.8 | 15.9 | 114.5 | 18.1 | 5.7 | 1.6 |

| IKAm | C | LS | 4.6 | 4.0 | 69.1 | 62.8 | 96.5 | 96.1 | 47.0 | 28.2 | 13.1 | 30.4 | 6.5 | 57.3 | 8.5 | 62.7 | 11.0 | 8.6 | 1.6 |

| THEm | C | LS | 5.1 | 4.3 | 13.3 | 44.5 | 39.3 | 72.9 | 43.4 | 34.4 | 21.3 | 26.5 | 32.0 | 41.9 | 4.3 | 44.6 | 13.6 | 4.0 | 1.6 |

| ARK | C | SS | 7.8 | 5.9 | 8.9 | 54.2 | 43.1 | 64.5 | 13.3 | 54.8 | 16.5 | 11.9 | 17.3 | 51.5 | 10.3 | 54.3 | 16.3 | 3.3 | 3.2 |

| ARX | C | SS | 2.5 | 3.5 | 21.0 | 87.2 | 54.7 | 119.1 | 44.3 | 66.2 | 28.6 | 41.3 | 27.6 | 83.9 | 10.6 | 87.4 | 10.0 | 9.7 | 0.8 |

| ATHm | C | SS | 8.1 | 5.6 | 21.9 | 47.1 | 55.5 | 56.7 | 41.3 | 25.4 | 19.2 | 13.0 | 16.2 | 44.2 | 6.2 | 47.2 | 13.8 | 14.6 | 3.0 |

| DIMm | C | SS | 5.0 | 5.3 | 21.4 | 44.9 | 121.0 | 100.7 | 31.4 | 37.6 | 29.7 | 26.1 | 10.9 | 44.0 | 17.7 | 44.8 | 10.5 | 3.9 | 2.6 |

| PEL | C | SS | 2.7 | 3.8 | 9.1 | 101.4 | 59.8 | 70.9 | 19.2 | 89.6 | 22.8 | 36.3 | 11.1 | 86.3 | 13.8 | 101.3 | 33.8 | 5.4 | 1.2 |

| SAMm | C | SS | 14.8 | 3.0 | 28.0 | 36.4 | 77.4 | 46.4 | 21.1 | 28.5 | 5.3 | 60.3 | 20.0 | 35.2 | 5.2 | 36.3 | 9.8 | 5.5 | 0.8 |

| Genotype Class | |||||||||||||||||||

| L | 5.0 | 4.4 | 24.5 | 65.1 | 117.6 | 80.1 | 41.4 | 49.5 | 22.2 | 38.3 | 25.5 | 8.8 | 17.3 | 65.0 | 33.8 | 17.7 | 2.9 | ||

| C | 20.4 | 4.9 | 30.2 | 65.7 | 92.3 | 89.0 | 52.4 | 56.1 | 20.3 | 41.5 | 29.5 | 13.9 | 11.4 | 65.9 | 34.5 | 16.2 | 3.2 | ||

| Seed Size | |||||||||||||||||||

| LS | 19.2 | 4.2 | 42.9 | 72.1 | 93.5 | 84.8 | 64.5 | 50.6 | 20.9 | 66.5 | 32.4 | 67.4 | 12.2 | 72.3 | 12.2 | 8.9 | 2.6 | ||

| SS | 10.1 | 4.6 | 22.0 | 67.8 | 112.9 | 80.2 | 40.9 | 51.6 | 21.5 | 33.8 | 25.0 | 65.9 | 16.6 | 67.6 | 23.6 | 12.1 | 3.1 | ||

| Number of Plants at Harvest (NP; Plants per m2) | Seed Yield (SY; kg ha−1) | Seed Yield Loss Percentage (SYLP; %) | Seed Yield Loss (SYL; kg ha−1) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | ||||||

| 2020/2021 | 22.7 ± 0.7 a | 899 ± 65 a | 8.6 ± 1.0 a | 47 ± 3 a | ||

| 2021/2022 | 23.6 ± 0.6 a | 826 ± 58 a | 6.8 ± 0.7 a | 45 ± 4 a | ||

| Genotype | ||||||

| ID | Genotype Class | Seed Size | ||||

| DOM_Ldr | L | LS | 20.7 ± 1.9 abcde | 1231 ± 296 bcdef | 8.7 ± 1.6 bc | 102 ± 26 a |

| LA2 large | L | LS | 14.1 ± 2.1 e | 765 ± 177 fghijklm | 14.6 ± 5.8 abc | 67 ± 12 abc |

| APK_Ldr | L | SS | 27.8 ± 1.2 ab | 858 ± 200 defghijk | 7.4 ± 4.8 bc | 33 ± 9 bc |

| BEL | L | SS | 30.0 ± 1.2 a | 1252 ± 293 bcde | 2.4 ± 0.6 c | 28 ± 7 bc |

| CHR | L | SS | 25.6 ± 2.6 abc | 291 ± 101 mn | 23.4 ± 7.5 a | 44 ± 5 abc |

| DIG | L | SS | 25.2 ± 1.8 abc | 1437 ± 344 bc | 2.8 ± 0.7 c | 49 ± 18 abc |

| DIL | L | SS | 23.0 ± 1.9 abcde | 328 ± 100 lmn | 11.9 ± 3.9 abc | 52 ± 25 abc |

| EGL | L | SS | 25. 2 ± 1.2 abc | 1449 ± 247 bc | 4.7 ± 1.0 c | 62 ± 10 abc |

| EGL_Ldr | L | SS | 25.2 ± 1.4 abcd | 1324 ± 195 bcd | 6.3 ± 0.8 c | 80 ± 9 abc |

| GER | L | SS | 26.3 ± 1.3 abc | 547 ± 140 hijklmn | 9.7 ± 3.5 abc | 33 ± 8 bc |

| GYT | L | SS | 22.6 ± 2.1 abcde | 788 ± 170 efghijkl | 4.9 ± 1.2 bc | 40 ± 12 abc |

| IER | L | SS | 22.2 ± 1.8 abcde | 536 ± 124 hijklmn | 18.8 ± 3.8 ab | 95 ± 23 ab |

| KOR | L | SS | 23.7 ± 1.1 abcde | 627 ± 154 hijklmn | 11.6 ± 3.6 abc | 56 ± 21 abc |

| KOZ | L | SS | 21.9 ± 1.8 abcde | 1265 ± 164 bcde | 2.5 ± 0.8 c | 34 ± 12 bc |

| LA1 | L | SS | 17.8 ± 3.0 cde | 272 ± 88 n | 8.5 ± 2.2 bc | 19 ± 7 c |

| LAX | L | SS | 29.6 ± 1.5 a | 1930 ± 120 a | 1.9 ± 0.3 c | 39 ± 8 abc |

| MOL | L | SS | 23.0 ± 1.6 abcde | 945 ± 220 defghi | 3.5 ± 0.6 c | 33 ± 9 bc |

| MOL_Ldr | L | SS | 22.2 ± 3.7 abcde | 884 ± 168 defghij | 2.5 ± 0.7 c | 21 ± 8 c |

| PRG | L | SS | 25.9 ± 1.9 abc | 1013 ± 334 cdefgh | 1.7 ± 0.5 c | 17 ± 8 c |

| PTO | L | SS | 21.1 ± 2.1 abcde | 754 ± 147 fghijklm | 7.5 ± 1.5 bc | 50 ± 10 abc |

| RIZ | L | SS | 27.8 ± 1.6 ab | 1109 ± 140 bcdefg | 3.2 ± 0.4 c | 36 ± 6 abc |

| TSO | L | SS | 15.6 ± 3.8 de | 1559 ± 218 ab | 3.1 ± 0.7 c | 53 ± 14 abc |

| ELPm | C | LS | 16.8 ± 5.9 cde | 387 ± 181 klmn | 12.9 ± 5.4 abc | 20 ± 5 c |

| IKAm | C | LS | 23.0 ± 1.2 abcde | 533 ± 159 hijklmn | 3.2 ± 1.6 c | 20 ± 10 c |

| THEm | C | LS | 25.9 ± 0.9 abc | 707 ± 128 ghijklmn | 9.4 ± 1.5 bc | 71 ± 21 abc |

| ARK | C | SS | 20.8 ± 1.8 abcde | 906 ± 201 defghij | 6.7 ± 1.2 bc | 56 ± 15 abc |

| ARX | C | SS | 22.2 ± 1.9 abcde | 462 ± 164 jklmn | 5.7 ± 1.3 c | 30 ± 15 bc |

| ATHm | C | SS | 24.1 ± 2.1 abcd | 901 ± 173 defghij | 5.5 ± 1.3 bc | 51 ± 12 abc |

| DIMm | C | SS | 24.1 ± 0.9 abcd | 650 ± 119 ghijklmn | 11.9 ± 5.9 abc | 63 ± 26 abc |

| PEL | C | SS | 19.3 ± 2.2 bcde | 488 ± 202 ijklmn | 13.6 ± 3.3 abc | 41 ± 12 abc |

| SAMm | C | SS | 20.7 ± 1.9 abcde | 454 ± 68 jklmn | 6.7 ± 2.1 bc | 24 ± 5 c |

| Source of Variance | df | |||||

| FYear | 1 | 2.523 ns | 1.184 ns | 3.257 ns | 0.092 ns | |

| FGenotype | 30 | 4.431 *** | 5.827 *** | 4.139 *** | 2.994 *** | |

| FYear × Genotype | 30 | 3.782 *** | 2.182 ** | 2.636 *** | 2.316 *** | |

| Genotype Class | ||||||

| L | 23.7 ± 0.5 a | 23.7 ± 0.5 a | 7.3 ± 0.8 a | 47 ± 3 a | ||

| C | 21.6 ± 0.9 b | 21.6 ± 0.9 b | 8.5 ± 1.1 a | 43 ± 5 a | ||

| Source of Variance | df | |||||

| FYear | 1 | 3.992 ns | 0.074 ns | 3.292 ns | 0.125 ns | |

| FGenotype Class | 1 | 5.292 * | 14.049 *** | 1.022 ns | 0.319 ns | |

| FYear × Genotype Class | 1 | 6.872 ** | 1.284 ns | 1.990 ns | 0.181 ns | |

| Seed Size | ||||||

| LS | 18.5 ± 1.4 b | 18.5 ± 1.4 b | 10.1 ± 1.8 a | 58 ± 9 a | ||

| SS | 24.0 ± 0.4 a | 24.0 ± 0.4 a | 7.2 ± 0.7 a | 44 ± 3 b | ||

| Source of Variance | df | |||||

| FYear | 1 | 3.560 ns | 1.391 ns | 2.663 ns | 0.029 ns | |

| FSeed Size | 1 | 23.491 *** | 1.480 ns | 2.945 ns | 3.978 * | |

| FYear × Seed Size | 1 | 2.712 ns | 5.342 * | 5.338 * | 0.168 ns | |

| Biological Yield (BY; kg ha−1) | Harvest Index (HI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | ||||

| 2020/2021 | 4759 ± 221 a | 0.187 ± 0.010 a | ||

| 2021/2022 | 4442 ±207 a | 0.190 ± 0.011 a | ||

| Genotype | ||||

| ID | Genotype Class | Seed Size | ||

| DOM_Ldr | L | LS | 6979 ± 1239 ab | 0.167 ± 0.028 efghi |

| LA2 large | L | LS | 4782 ± 901 cdefghi | 0.155 ± 0.029 fghij |

| APK_Ldr | L | SS | 4778 ± 398 cdefghi | 0.172 ± 0.034 efghi |

| BEL | L | SS | 6438 ± 794 abc | 0.190 ± 0.025 defgh |

| CHR | L | SS | 3970 ± 441 hijkl | 0.075 ± 0.024 j |

| DIG | L | SS | 4521 ± 1277 efghij | 0.346 ± 0.022 a |

| DIL | L | SS | 3032 ± 729 jklm | 0.104 ± 0.016 ij |

| EGL | L | SS | 7212 ± 680 a | 0.195 ± 0.021 defgh |

| EGL_Ldr | L | SS | 5999 ± 463 abcde | 0.216 ± 0.024 cdefg |

| GER | L | SS | 4444 ± 470 efghij | 0.132 ± 0.037 hij |

| GYT | L | SS | 4021 ± 797 ghijkl | 0.218 ± 0.052 cdefg |

| IER | L | SS | 4268 ± 412 fghijk | 0.147 ± 0.047 ghij |

| KOR | L | SS | 5217 ± 687 cdefghi | 0.126 ± 0.030 hij |

| KOZ | L | SS | 4623 ± 695 efghij | 0.284 ± 0.019 abc |

| LA1 | L | SS | 2593 ± 371 klm | 0.107 ± 0.037 ij |

| LAX | L | SS | 5997 ± 379 abcde | 0.326 ± 0.022 ab |

| MOL | L | SS | 4220 ± 749 fghijk | 0.215 ± 0.032 cdefg |

| MOL_Ldr | L | SS | 3613 ± 538 ijkl | 0.232 ± 0.021 cdef |

| PRG | L | SS | 4695 ± 368 defghij | 0.096 ± 0.035 ij |

| PTO | L | SS | 3594 ± 788 ijkl | 0.256 ± 0.034 bcd |

| RIZ | L | SS | 5817 ± 543 abcdef | 0.133 ± 0.024 hij |

| TSO | L | SS | 4193 ± 590 fghijk | 0.267 ± 0.015 abcd |

| ELPm | C | LS | 6393 ± 638 abcd | 0.238 ± 0.019 cde |

| IKAm | C | LS | 1703 ± 424 m | 0.222 ± 0.062 cdefg |

| THEm | C | LS | 2350 ± 521 lm | 0.206 ± 0.026 cdefgh |

| ARK | C | SS | 5689 ± 1007 abcdefg | 0.130 ± 0.018 hij |

| ARX | C | SS | 5662 ± 306 abcdefgh | 0.159 ± 0.036 efghi |

| ATHm | C | SS | 4036 ± 730 ghijkl | 0.105 ± 0.028 ij |

| DIMm | C | SS | 5274 ± 889 bcdefghi | 0.171 ± 0.018 efghi |

| PEL | C | SS | 4132 ± 529 fghijkl | 0.159 ± 0.024 efghi |

| SAMm | C | SS | 4695 ± 368 defghij | 0.096 ± 0.035 ij |

| Source of Variance | df | |||

| FYear | 1 | 1.898 ns | 0.093 ns | |

| FGenotype | 30 | 5.306 *** | 5.783 *** | |

| FYear × Genotype | 30 | 2.152 ** | 1.769 * | |

| Genotype Class | ||||

| L | 12.8 ± 0.4 a | 4850 ± 175 a | ||

| C | 9.9 ± 0.6 b | 3942 ± 284 b | ||

| Source of Variance | df | |||

| FYear | 1 | 0.137 ns | 0.325 ns | |

| FGenotype Class | 1 | 7.720 ** | 2.994 ns | |

| FYear × Genotype Class | 1 | 1.259 ns | 0.376 ns | |

| Seed Size | ||||

| LS | 12.0 ± 1.4 a | 4389 ± 526 a | ||

| SS | 11.9 ± 0.3 a | 4627 ± 151 a | ||

| Source of Variance | df | |||

| FYear | 1 | 0.091 ns | 3.248 ns | |

| FSeed Size | 1 | 0.204 ns | 0.644 ns | |

| FYear × Seed Size | 1 | 0.633 ns | 5.438 * | |

| Plant Height (PH; cm) | Number of Branches per Plant (NBP) | Leaf Area per Plant (LAP; cm2) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | |||||

| 2020/2021 | 21.3 ± 0.4 b | 10.8 ± 0.5 b | 649 ± 19 a | ||

| 2021/2022 | 27.0 ± 0.5 a | 13.1 ± 0.4 a | 574 ± 14 b | ||

| Genotype | |||||

| ID | Genotype Class | Seed Size | |||

| DOM_Ldr | L | LS | 26.1 ± 3.4 abc | 19.3 ± 5.4 a | 747 ± 82 abcd |

| LA2 large | L | LS | 25.0 ± 2.5 abcde | 13.9 ± 2.2 bcd | 728 ± 70 abcde |

| APK_Ldr | L | SS | 25.7 ± 1.5 abc | 11.3 ± 0.7 cde | 663 ± 47 cdefgh |

| BEL | L | SS | 26.3 ± 1.4 abc | 13.6 ± 1.4 bcd | 533 ± 65 hijkl |

| CHR | L | SS | 18.2 ± 1.9 e | 12.9 ± 2.1 bcde | 551 ± 55 ghijkl |

| DIG | L | SS | 23.7 ± 1.8 abcde | 10.0 ± 1.6 de | 610 ± 53 defghijk |

| DIL | L | SS | 22.2 ± 1.2 abcde | 8.5 ± 0.9 ef | 583 ± 86 fghijk |

| EGL | L | SS | 22.4 ± 1.7 abcde | 14.0 ± 1.4 bcd | 724 ± 68 abcdef |

| EGL_Ldr | L | SS | 25.7 ± 2.3 abc | 13.2 ± 1.2 bcd | 586 ± 37 efghijk |

| GER | L | SS | 29.2 ± 2.0 a | 13.4 ± 1.1 bcd | 517 ± 50 ijkl |

| GYT | L | SS | 25.5 ± 1.0 abcd | 11.1 ± 0.4 cde | 588 ± 65 efghijk |

| IER | L | SS | 22.0 ± 1.0 abcde | 10.9 ± 1.0 cde | 835 ± 54 ab |

| KOR | L | SS | 25.4 ± 2.7 abcde | 14.4 ± 1.4 bcd | 469 ± 29 kl |

| KOZ | L | SS | 26.3 ± 2.5 abc | 11.3 ± 1.5 cde | 608 ± 54 defghijk |

| LA1 | L | SS | 20.4 ± 1.3 bcde | 11.0 ± 2.4 cde | 661 ± 61 cdefghi |

| LAX | L | SS | 26.6 ± 1.8 abc | 10.6 ± 0.4 cde | 529 ± 43 hijkl |

| MOL | L | SS | 19.5 ± 1.6 cde | 16.6 ± 2.4 ab | 656 ± 35 cdefghi |

| MOL_Ldr | L | SS | 20.2 ± 0.9 bcde | 14.7 ± 2.5 bc | 573 ± 46 ghijk |

| PRG | L | SS | 19.8 ± 0.5 cde | 14.4 ± 2.4 bcd | 591 ± 59 efghijk |

| PTO | L | SS | 28.5 ± 1.7 a | 10.5 ± 0.7 cde | 784 ± 53 abc |

| RIZ | L | SS | 18.4 ± 1.9 de | 13.3 ± 0.9 bcd | 541 ± 39 ghijkl |

| TSO | L | SS | 25.1 ± 2.0 abcde | 12.1 ± 1.0 bcde | 752 ± 67 abcd |

| ELPm | C | LS | 27.1 ± 1.6 ab | 5.0 ± 0.6 f | 404 ± 33 l |

| IKAm | C | LS | 26.8 ± 1.5 abc | 10.7 ± 1.4 cde | 876 ± 29 a |

| THEm | C | LS | 27.7 ± 2.4 a | 11.1 ± 1.2 cde | 690 ± 102 bcdefg |

| ARK | C | SS | 25.7 ± 1.7 abc | 10.5 ± 0.5 cde | 562 ± 40 ghijk |

| ARX | C | SS | 20.4 ± 2.4 bcde | 12.2 ± 2.0 bcde | 620 ± 70 defghij |

| ATHm | C | SS | 24.0 ± 1.9 abcde | 12.3 ± 0.7 bcde | 504 ± 33 jkl |

| DIMm | C | SS | 24.1 ± 2.9 abcde | 11.7 ± 1.2 cde | 535 ± 24 hijkl |

| PEL | C | SS | 26.4 ± 2.5 abc | 12.6 ± 1.9 bcde | 589 ± 27 efghijk |

| SAMm | C | SS | 24.9 ± 0.5 abcde | 4.3 ± 1.1 f | 402 ± 36 l |

| Source of Variance | df | ||||

| FYear | 1 | 142.801 *** | 14.785 *** | 16.351 *** | |

| FGenotype | 30 | 5.183 *** | 3.161 *** | 4.418 *** | |

| FYear × Genotype | 30 | 2.116 ** | 1.394 ns | 1.056 ns | |

| Genotype Class | |||||

| L | 23.7 ± 0.4 a | 12.8 ± 0.4 a | 628 ± 14 a | ||

| C | 25.2 ± 0.7 a | 9.9 ± 0.6 b | 567 ± 23 b | ||

| Source of Variance | df | ||||

| FYear | 1 | 53.962 *** | 9.038 ** | 4.237 * | |

| FGenotype Class | 1 | 3.273 ns | 15.757 *** | 5.190 * | |

| FYear × Genotype Class | 1 | 0.371 ns | 0.002 ns | 3.426 ns | |

| Seed Size | |||||

| LS | 26.6 ± 1.0 a | 12.0 ± 1.4 a | 679 ± 42 a | ||

| SS | 23.7 ± 0.4 b | 11.9 ± 0.3 a | 600 ± 12 b | ||

| Source of Variance | df | ||||

| FYear | 1 | 35.704 *** | 2.969 * | 4.036 * | |

| FSeed Size | 1 | 8.372 ** | 0.003 ns | 5.778 * | |

| FYear × Seed Size | 1 | 0.089 ns | 0.849 ns | 0.137 ns | |

| Number of Pods per Plant (NPP) | Number of Seeds per Pod (NSP) | Seed Yield per Plant (SYP; g) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | |||||

| 2020/2021 | 66.6 ± 4.9 a | 1.42 ± 0.03 b | 2.68 ± 0.19 a | ||

| 2021/2022 | 55.9 ± 4.1 b | 1.47 ± 0.02 a | 2.47 ± 0.17 a | ||

| Genotype | |||||

| ID | Genotype Class | Seed Size | |||

| DOM_Ldr | L | LS | 52.0 ± 11.5 fghijk | 1.28 ± 0.05 hijkl | 3.69 ± 0.89 bcdef |

| LA2 large | L | LS | 33.7 ± 7.0 hijkl | 1.18 ± 0.09 kl | 2.29 ± 0.53 fghijklm |

| APK_Ldr | L | SS | 60.8 ± 12.0 efghi | 1.54 ± 0.05 bcdefghi | 2.58 ± 0.60 defghijk |

| BEL | L | SS | 99.4 ± 21.0 bcd | 1.54 ± 0.04 bcdefghi | 3.76 ± 0.88 bcde |

| CHR | L | SS | 37.8 ± 8.5 hijkl | 1.24 ± 0.21 jkl | 0.87 ± 0.30 mn |

| DIG | L | SS | 112.0 ± 29.7 abc | 1.83 ± 0.03 ab | 4.31 ± 1.03 bc |

| DIL | L | SS | 27.7 ± 8.6 ijkl | 1.31 ± 0.04 ghijkl | 1.15 ± 0.31 lmn |

| EGL | L | SS | 110.3 ± 17.7 abc | 1.51 ± 0.05 cdefghij | 4.35 ± 0.74 bc |

| EGL_Ldr | L | SS | 102.5 ± 15.1 bcd | 1.49 ± 0.03 cdefghij | 3.97 ± 0.59 bcd |

| GER | L | SS | 40.6 ± 8.5 hijkl | 1.44 ± 0.06 defghijk | 1.64 ± 0.42 hijklmn |

| GYT | L | SS | 52.9 ± 11.4 fghijk | 1.34 ± 0.05 fghijkl | 2.36 ± 0.51 efghijkl |

| IER | L | SS | 45.1 ± 11.6 ghijkl | 1.14 ± 0.04 l | 1.58 ± 0.45 hijklmn |

| KOR | L | SS | 42.0 ± 9.3 ghijkl | 1.57 ± 0.09 bcdefgh | 1.88 ± 0.46 hijklmn |

| KOZ | L | SS | 80.2 ± 9.7 cdef | 1.63 ± 0.03 abcde | 3.79 ± 0.49 bcde |

| LA1 | L | SS | 21.1 ± 5.8 kl | 1.39 ± 0.12 efghijkl | 0.82 ± 0.26 n |

| LAX | L | SS | 137.5 ± 6.3 a | 1.91 ± 0.04 a | 5.79 ± 0.36 a |

| MOL | L | SS | 88.1 ± 19.5 bcde | 1.70 ± 0.05 abcd | 2.84 ± 0.66 defghi |

| MOL_Ldr | L | SS | 73.6 ± 15.3 defg | 1.62 ± 0.03 abcdef | 2.65 ± 0.51 defghij |

| PRG | L | SS | 81.7 ± 25.7 cdef | 1.77 ± 0.07 abc | 3.04 ± 0.99 cdefgh |

| PTO | L | SS | 53.9 ± 8.4 fghij | 1.44 ± 0.05 defghijk | 2.26 ± 0.44 fghijklm |

| RIZ | L | SS | 83.7 ± 11.7 bcdef | 1.60 ± 0.07 bcdefg | 3.33 ± 0.42 bcdefg |

| TSO | L | SS | 115.0 ± 15.2 ab | 1.42 ± 0.02 defghijkl | 4.68 ± 0.65 ab |

| ELPm | C | LS | 18.4 ± 8.6 l | 1.32 ± 0.09 ghijkl | 1.16 ± 0.54 klmn |

| IKAm | C | LS | 22.5 ± 6.1 jkl | 1.26 ± 0.05 ijkl | 1.69 ± 0.48 hijklmn |

| THEm | C | LS | 31.1 ± 5.3 ijkl | 1.24 ± 0.02 jkl | 2.12 ± 0.39 ghijklmn |

| ARK | C | SS | 65.8 ± 13.8 efgh | 1.29 ± 0.05 hijkl | 2.72 ± 0.60 defghij |

| ARX | C | SS | 30.3 ± 12.5 ijkl | 1.38 ± 0.07 efghijkl | 1.28 ± 0.59 jklmn |

| ATHm | C | SS | 59.2 ± 10.7 efghi | 1.32 ± 0.03 ghijkl | 2.70 ± 0.52 defghij |

| DIMm | C | SS | 55.9 ± 10.0 efghij | 1.23 ± 0.09 jkl | 1.95 ± 0.36 ghijklmn |

| PEL | C | SS | 42.8 ± 15.1 ghijkl | 1.34 ± 0.08 fghijkl | 1.47 ± 0.61 ijklmn |

| SAMm | C | SS | 20.8 ± 3.0 kl | 1.45 ± 0.03 defghijk | 1.36 ± 0.20 jklmn |

| Source of Variance | df | ||||

| FYear | 1 | 6.319 ** | 5.995 * | 1.219 ns | |

| FGenotype | 30 | 7.537 *** | 12.830 *** | 5.634 *** | |

| FYear × Genotype | 30 | 2.447 *** | 3.973 *** | 2.154 ** | |

| Genotype Class | |||||

| L | 71.0 ± 4.0 a | 1.49 ± 0.02 a | 2.91 ± 0.15 a | ||

| C | 39.4 ± 3.9 b | 1.31 ± 0.01 b | 1.84 ± 0.17 b | ||

| Source of Variance | df | ||||

| FYear | 1 | 4.828 ** | 5.133 * | 0.029 ns | |

| FGenotype Class | 1 | 21.887 *** | 22.542 *** | 14.479 *** | |

| FYear × Genotype Class | 1 | 1.864 ns | 0.682 ns | 1.055 ns | |

| Seed Size | |||||

| LS | 32.1 ± 4.0 b | 1.26 ± 0.03 b | 2.21 ± 0.29 a | ||

| SS | 67.7 ± 3.6 a | 1.48 ± 0.02 a | 2.68 ± 0.14 a | ||

| Source of Variance | df | ||||

| FYear | 1 | 4.023 ** | 4.469 * | 1.146 ns | |

| FSeed Size | 1 | 18.14 *** | 22.695 *** | 1.899 ns | |

| FYear × Seed Size | 1 | 1.034 ns | 2.239 ns | 5.197 * | |

| Thousand Seed Weight (TSW; g) | Seed Diameter (SD; mm) | Seed Protein Content (SPC; %) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | |||||

| 2020/2021 | 30.52 ± 1.21 a | 4.94 ± 0.08 a | 21.76 ± 0.07 b | ||

| 2021/2022 | 31.79 ± 1.20 a | 4.83 ± 0.10 a | 22.23 ± 0.06 a | ||

| Genotype | |||||

| ID | Genotype Class | Seed Size | |||

| DOM_Ldr | L | LS | 54.94 ± 2.04 a | 6.35 ± 0.40 ab | 21.92 ± 0.07 bcdef |

| LA2 large | L | LS | 53.77 ± 1.15 a | 6.91 ± 0.16 a | 22.06 ± 0.12 bcdef |

| APK_Ldr | L | SS | 26.11 ± 0.84 defghi | 3.86 ± 0.48 f | 22.42 ± 0.13 b |

| BEL | L | SS | 24.26 ± 1.18 efghi | 4.39 ± 0.06 def | 21.50 ± 0.28 efg |

| CHR | L | SS | 18.44 ± 0.69 i | 3.94 ± 0.44 ef | 23.35 ± 0.10 a |

| DIG | L | SS | 22.29 ± 1.02 fghi | 4.26 ± 0.06 def | 22.44 ± 0.22 b |

| DIL | L | SS | 30.93 ± 1.45 cde | 4.82 ± 0.06 cdef | 22.47 ± 0.13 b |

| EGL | L | SS | 25.86 ± 0.67 defghi | 4.61 ± 0.09 def | 22.14 ± 0.06 bcd |

| EGL_Ldr | L | SS | 26.09 ± 0.71 defghi | 4.67 ± 0.09 def | 22.18 ± 0.32 bcd |

| GER | L | SS | 26.27 ± 1.18 defghi | 4.70 ± 0.06 cdef | 21.91 ± 0.36 bcdef |

| GYT | L | SS | 33.89 ± 1.80 cd | 4.99 ± 0.11 cd | 21.05 ± 0.14 g |

| IER | L | SS | 31.60 ± 3.03 cde | 4.95 ± 0.18 cd | 21.76 ± 0.15 cdef |

| KOR | L | SS | 27.14 ± 1.29 cdefgh | 4.57 ± 0.31 def | 22.15 ± 0.34 bcd |

| KOZ | L | SS | 28.93 ± 0.85 cdefg | 4.95 ± 0.05 cd | 22.08 ± 0.32 bcde |

| LA1 | L | SS | 26.71 ± 1.52 defghi | 4.70 ± 0.16 cdef | 22.40 ± 0.08 b |

| LAX | L | SS | 21.98 ± 0.64 ghi | 4.23 ± 0.06 def | 21.77 ± 0.25 cdef |

| MOL | L | SS | 18.71 ± 1.26 hi | 3.96 ± 0.07 ef | 22.19 ± 0.07 bcd |

| MOL_Ldr | L | SS | 22.83 ± 1.12 efghi | 4.31 ± 0.07 def | 21.48 ± 0.08 efg |

| PRG | L | SS | 20.64 ± 1.06 ghi | 4.11 ± 0.03 def | 21.73 ± 0.18 def |

| PTO | L | SS | 28.58 ± 1.42 cdefg | 4.79 ± 0.12 cdef | 22.23 ± 0.21 bcd |

| RIZ | L | SS | 25.84 ± 1.27 defghi | 4.55 ± 0.08 def | 21.98 ± 0.25 bcdef |

| TSO | L | SS | 28.41 ± 0.76 cdefg | 4.63 ± 0.06 def | 22.18 ± 0.09 bcd |

| ELPm | C | LS | 48.32 ± 3.57 ab | 6.59 ± 0.15 ab | 21.03 ± 0.14 g |

| IKAm | C | LS | 56.50 ± 2.72 a | 6.31 ± 0.24 ab | 22.35 ± 0.17 bc |

| THEm | C | LS | 55.20 ± 3.05 a | 6.37 ± 0.10 ab | 22.36 ± 0.15 bc |

| ARK | C | SS | 30.48 ± 2.02 cdef | 4.95 ± 0.07 cd | 21.51 ± 0.28 efg |

| ARX | C | SS | 25.61 ± 1.04 defghi | 4.40 ± 0.19 def | 22.34 ± 0.07 bcd |

| ATHm | C | SS | 35.24 ± 1.99 c | 4.72 ± 0.28 cdef | 21.45 ± 0.26 fg |

| DIMm | C | SS | 28.15 ± 1.21 cdefg | 4.91 ± 0.08 cde | 22.27 ± 0.24 bcd |

| PEL | C | SS | 23.04 ± 3.18 efghi | 4.52 ± 0.10 def | 22.34 ± 0.11 bc |

| SAMm | C | SS | 45.12 ± 1.81 b | 5.66 ± 0.13 bc | 20.98 ± 0.07 g |

| Source of Variance | df | ||||

| FYear | 1 | 3.181 ns | 3.435 ns | 132.31 *** | |

| FGenotype | 30 | 51.274 *** | 19.773 *** | 19.551 *** | |

| FYear × Genotype | 30 | 1.897 ** | 1.248 ns | 7.296 *** | |

| Genotype Class | |||||

| L | 28.31 ± 0.83 b | 4.69 ± 0.07 b | 22.06 ± 0.06 a | ||

| C | 38.20 ± 1.80 a | 5.38 ± 0.12 a | 21.84 ± 0.09 b | ||

| Source of Variance | df | ||||

| FYear | 1 | 0.045 ns | 0.742 ns | 25.234 *** | |

| FGenotype Class | 1 | 27.736 *** | 20.567 *** | 4.937 * | |

| FYear × Genotype Class | 1 | 0.370 ns | 0.107 ns | 0.832 ns | |

| Seed Size | |||||

| LS | 53.49 ± 1.21 a | 6.50 ± 0.11 a | 21.94 ± 0.11 a | ||

| SS | 26.98 ± 0.51 b | 4.58 ± 0.04 b | 22.01 ± 0.05 a | ||

| Source of Variance | df | ||||

| FYear | 1 | 0.009 ns | 1.005 ns | 7.112 ** | |

| FSeed Size | 1 | 444.027 *** | 287.328 *** | 0.925 ns | |

| FYear × Seed Size | 1 | 0.533 ns | 0.186 ns | 2.198 ns | |

| Parameters | Factor-1 | Factor-2 | Factor-3 | Factor-4 | Factor-5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TF | 0.216 | 0.775 | −0.232 | 0.119 | −0.291 |

| TM | −0.057 | 0.741 | −0.075 | 0.590 | 0.127 |

| NP | 0.375 | 0.288 | −0.194 | −0.377 | 0.439 |

| SY | 0.955 | −0.125 | 0.189 | 0.033 | 0.021 |

| SYLP | −0.474 | 0.416 | 0.284 | −0.421 | 0.214 |

| SYL | 0.334 | 0.332 | 0.657 | −0.201 | 0.150 |

| BY | 0.711 | 0.343 | 0.384 | −0.249 | 0.081 |

| HI | 0.590 | −0.549 | −0.038 | 0.340 | −0.026 |

| PH | 0.146 | 0.225 | 0.325 | 0.471 | 0.554 |

| NBP | 0.330 | 0.453 | 0.141 | 0.134 | −0.446 |

| LAP | 0.149 | 0.247 | 0.413 | −0.249 | −0.504 |

| NPP | 0.952 | −0.047 | 0.015 | −0.118 | −0.006 |

| NSP | 0.549 | −0.261 | −0.559 | 0.307 | −0.027 |

| SYP | 0.945 | −0.120 | 0.188 | 0.042 | 0.021 |

| TSW | −0.313 | −0.289 | 0.738 | 0.363 | −0.034 |

| SD | −0.279 | −0.297 | 0.765 | 0.288 | −0.094 |

| SPC | −0.047 | 0.800 | −0.117 | 0.329 | −0.018 |

| Eigenvalue | 4.74 | 3.17 | 2.58 | 1.64 | 1.14 |

| Variability (%) | 27.89 | 18.62 | 15.20 | 9.63 | 6.72 |

| Cumulative (%) | 27.89 | 46.51 | 61.71 | 71.34 | 78.06 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bakoulopoulou, I.; Roussis, I.; Kakabouki, I.; Tigka, E.; Stavropoulos, P.; Mavroeidis, A.; Karydogianni, S.; Bilalis, D.; Papastylianou, P. Exploring Phenological and Agronomic Parameters of Greek Lentil Landraces for Developing Climate-Resilient Cultivars Adapted to Mediterranean Conditions. Crops 2025, 5, 91. https://doi.org/10.3390/crops5060091

Bakoulopoulou I, Roussis I, Kakabouki I, Tigka E, Stavropoulos P, Mavroeidis A, Karydogianni S, Bilalis D, Papastylianou P. Exploring Phenological and Agronomic Parameters of Greek Lentil Landraces for Developing Climate-Resilient Cultivars Adapted to Mediterranean Conditions. Crops. 2025; 5(6):91. https://doi.org/10.3390/crops5060091

Chicago/Turabian StyleBakoulopoulou, Iakovina, Ioannis Roussis, Ioanna Kakabouki, Evangelia Tigka, Panteleimon Stavropoulos, Antonios Mavroeidis, Stella Karydogianni, Dimitrios Bilalis, and Panayiota Papastylianou. 2025. "Exploring Phenological and Agronomic Parameters of Greek Lentil Landraces for Developing Climate-Resilient Cultivars Adapted to Mediterranean Conditions" Crops 5, no. 6: 91. https://doi.org/10.3390/crops5060091

APA StyleBakoulopoulou, I., Roussis, I., Kakabouki, I., Tigka, E., Stavropoulos, P., Mavroeidis, A., Karydogianni, S., Bilalis, D., & Papastylianou, P. (2025). Exploring Phenological and Agronomic Parameters of Greek Lentil Landraces for Developing Climate-Resilient Cultivars Adapted to Mediterranean Conditions. Crops, 5(6), 91. https://doi.org/10.3390/crops5060091