1. Introduction

China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is a transnational economic strategy introduced by President Xi Jinping in 2013 during a visit to Kazakhstan. It aims to promote policy coordination, infrastructure connectivity, trade facilitation, financial integration, and people-to-people bonds among participating countries, with no exclusive target countries but rather open to all willing partners. In the decade since its inception, the BRI has attracted widespread international attention as a driver of regional economic cooperation and development. Among the many sectors influenced by the BRI, the automotive industry has emerged in recent years as a significant focus for collaboration. This industry is an important engine of technological innovation and industrial transformation globally, and it has drawn increasing interest from emerging economies along the BRI route in their pursuit of industrial modernization. The cooperation between China and Kazakhstan in the automotive sector under the BRI framework is a particularly promising example of this trend, marrying China’s industrial capacity with Kazakhstan’s development ambitions.

China has been the world’s largest automobile producer and seller for fifteen consecutive years, and, in 2023, China’s automobile exports reached 4.91 million units, officially surpassing Japan to become the world’s largest automobile exporter. This milestone reflects China’s broader economic rise in the 21st century, sometimes characterized as the advent of a “Chinese Century”. However, alongside its rapid growth, China’s automotive industry faces challenges of domestic market saturation and the urgent need for structural upgrading. Transitioning from being a large automobile-producing country to a globally competitive automotive power has become a critical goal for China’s policymakers. The Chinese government’s strategic plan “Made in China 2025” explicitly identifies the automotive industry as a priority sector for enhancing innovation and international competitiveness. This plan urges Chinese automakers to leverage opportunities like the BRI to expand into overseas markets, thereby upgrading the automotive value chain and reducing overcapacity at home. Research suggests that participation in BRI projects can indeed contribute positively to innovation in advanced manufacturing industries in China. In line with these strategies, Chinese automakers are encouraged to accelerate market development in BRI countries and ultimately aim to penetrate European and other global markets.

Kazakhstan, for its part, has articulated bold aspirations for its automotive industry despite its late start. The national development strategy “Kazakhstan–2050” and the Third Modernization Plan both prioritize accelerating the modernization of the domestic automotive industry. In 2019, the Kazakh government introduced the “Automobile Production Development Roadmap 2019–2024,” a policy framework to support the growth of local automobile production through incentives and capacity-building measures. These initiatives underscore Kazakhstan’s commitment to diversifying its economy by developing manufacturing sectors such as automotive, reducing its historical over-reliance on extractive industries. Notably, the development goals of China and Kazakhstan in the automotive field show a high degree of alignment, making their cooperation increasingly important and mutually beneficial.

The industrial complementarities between China and Kazakhstan provide a strong foundation for collaboration. China’s domestic automobile market is enormous, total vehicle ownership in China reached approximately 353 million in 2024 and Chinese automakers are seeking new markets abroad for their expanding production capacity. In contrast, Kazakhstan’s vehicle ownership is relatively low (about 5.74 million registered motor vehicles as of early 2025). Kazakhstan’s automotive market has largely been supplied by imports, and there is substantial room for growth in vehicle penetration. Chinese cars, which offer a competitive price-to-quality ratio, have been well received in Kazakhstan, finding a niche between the higher-priced Western/Japanese models and lower-priced Russian models. Moreover, Kazakhstan’s strategic geographic location at the crossroads of Europe and Asia combined with its membership in the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) makes it an ideal gateway for Chinese automobiles to enter neighboring Central Asian markets and even Eastern Europe under the BRI framework.

There is also a structural economic synergy in this partnership. Kazakhstan’s economy has historically suffered from a narrow industrial base (dominated by oil, gas, and minerals) and urgently needs to develop manufacturing industries to achieve diversification and sustainable growth. The automotive industry, being capital-intensive, knowledge-intensive, and having long value chains with strong multiplier effects, is seen as a catalyst for industrialization. Studies indicate that one job in automotive manufacturing can create four or more jobs in related industries. The sector’s growth can spur the development of supporting infrastructure, logistics, and services, thereby strengthening the broader economic network. Kazakhstan’s current automotive manufacturing relies heavily on foreign assembly operations, and it does not yet have indigenous auto brands. In contrast, China has developed a comprehensive automotive industrial chain over the past decades, though it now faces issues of overcapacity and a plateauing domestic market. Through capacity cooperation and technology transfer, China can assist Kazakhstan in building up local automotive production capabilities from simple assembly to eventually manufacturing components locally, thus helping Kazakhstan upgrade its industrial base and reduce dependence on imports. At the same time, such cooperation allows Chinese firms to utilize their excess capacity, enter new markets, and move up the value chain, aligning with China’s strategic goals for its automotive industry.

The geopolitical context further amplifies the significance of Sino-Kazakh automotive cooperation. Kazakhstan is the largest economy in Central Asia and a pivotal state in the overland “Silk Road Economic Belt” component of the BRI. Successful industrial projects in Kazakhstan can have a demonstration effect for other countries along the BRI, showcasing the benefits of partnering with China in high-value manufacturing. Additionally, deepening economic ties with Kazakhstan supports China’s broader strategy of “opening up to the West”—balancing its international economic engagements more evenly between eastern (Asia-Pacific) and western (Eurasian) directions. Tangible achievements in the automotive sector not only contribute to Kazakhstan’s economic development but also strengthen bilateral relations and potentially draw more regional countries into mutually beneficial cooperation with China. In this sense, the China–Kazakhstan automotive partnership holds strategic value beyond its economic dimensions, reinforcing diplomatic and people-to-people ties under the BRI umbrella.

Despite a growing body of research on BRI-related economic cooperation, relatively few studies have focused on Kazakhstan’s automotive industry as a standalone case. Much of the literature examines broader regional trends or China–Central Asia relations in general. This paper seeks to fill that gap by providing an in-depth analysis of the China–Kazakhstan automotive industry cooperation as a distinct project under the BRI. By examining this case, we aim to identify long-term challenges and recent developments that shed light on the dynamics of China’s strategic partnership with Kazakhstan. The structure of this paper is as follows:

Section 2 establishes the theoretical framework and background, reviewing relevant literature and context on BRI cooperation and automotive industry developments in both countries.

Section 3 describes the methodology, which involves qualitative content analysis of various sources to trace the evolution of the cooperation.

Section 4 presents the analysis of the China–Kazakhstan automotive cooperation, divided into three phases, and discusses the current status and how sustainable growth can be ensured moving forward. Finally,

Section 5 concludes with a summary of findings and specific recommendations to promote the long-term stability and mutual benefits of the cooperation.

2. Materials and Methods

The Belt and Road Initiative forms the macro-context for China–Kazakhstan economic cooperation. Although the BRI does not designate specific target countries, Kazakhstan was de facto an early focal point due to President Xi’s announcement in Astana and Kazakhstan’s enthusiastic response. The BRI’s inclusive approach means that any country along the route that welcomes Chinese trade and investment and offers a stable partnership can become a priority cooperation partner. In the case of Kazakhstan, scholars have noted that the country’s active participation in BRI projects is both an opportunity and a necessity. Kazakhstan’s unique landlocked geography makes it dependent on robust overland links to major markets; hence, it stands to gain significantly from the transcontinental logistics and infrastructure corridors promoted by the BRI. By leveraging BRI investments, Kazakhstan can transform into an important transportation and logistics hub connecting China, Russia, and Europe, which would greatly enhance its geopolitical and economic stature.

From China’s perspective, the BRI is a platform to foster economic ties in Central Asia and beyond, especially in the context of shifting global dynamics. Analysts observe that in the face of challenges such as the COVID-19 pandemic and heightened geopolitical competition (e.g., strains in China–U.S. relations and sanctions on Russia), China has strong incentives to deepen cooperation with Central Asian countries to secure new markets and supply chains. Central Asia, with Kazakhstan as the largest economy, is seen as a critical region for China’s “westward” economic outreach. By investing in Kazakhstan’s industrial projects, China not only addresses overcapacity in its own industries but also strengthens economic interdependence in a region where it aims to maintain influence alongside other powers.

A number of studies have examined the evolving China–Kazakhstan relationship under the BRI. Cheng [

1] noted that China’s BRI has broad inclusion criteria and that political goodwill and mutual economic benefit are key conditions for cooperation. Scholars [

2] found that the BRI has significantly increased Chinese outward investment in the manufacturing sectors of participating emerging economies. Kazakhstan, as an emerging economy along the Belt, has indeed attracted substantial Chinese investment in manufacturing industries including automotive assembly. Research by JSC Samruk-Kazyna [

3] similarly observed positive impacts of BRI projects on trade volumes between China and partner countries, suggesting that initiatives under the BRI encourage deeper trade relations—Kazakhstan being no exception.

Kazakh scholars and policymakers [

4,

5,

6] emphasize the necessity for Kazakhstan to engage deeply with BRI to avoid overdependence on any single partner. One analysis highlighted that Kazakhstan must balance relations with major powers like China and Russia to overcome its geographic constraints (notably lack of sea access) and to fully capitalize on transit corridors such as the China–Europe railway routes that traverse its territory [

7,

8]. By doing so, Kazakhstan can reinforce its role as the key bridge in Eurasian overland trade. Another perspective underscored that Russia traditionally dominates northern Eurasian transit routes while China dominates the south; thus, Kazakhstan’s strategy has been to diversify its transit options and trade partnerships to bolster its own economic security and bargaining position. In this context, Sino-Kazakh cooperation is seen as having strategic complementarity: China gains a stable partner in Central Asia for its westward expansion, and Kazakhstan gains an investor and technology partner to reduce its historical reliance on Russia.

Kazakhstan’s domestic policy vision, embodied in the “Nurly Zhol” (Bright Path) new economic policy, aligns closely with the BRI. Ma [

9] points out that Nurly Zhol’s focus on improving transport infrastructure, industrial modernization, and connectivity mirrors the BRI’s objectives. This alignment of national strategies increases the synergy and shared interests in cooperation: both China and Kazakhstan prioritize infrastructure development, industrial diversification, and attracting foreign investment. Kazakhstan’s active participation in BRI projects, while maintaining its own national development priorities, allows it to attract foreign capital and technology without compromising its goal of balancing relationships with strategic partners.

Empirical analyses of Sino-Kazakh economic exchange underscore a pattern of complementary trade. Huang et al. [

10] used trade margin analysis to show that from 2002 to 2017, growth in China–Kazakhstan trade was largely driven by each country’s comparative advantages: Kazakhstan exported resource-intensive goods aligned with its natural endowments, while China exported a variety of manufactured goods leveraging its production capacity. This complementarity suggests that as cooperation deepens (for instance, with Kazakhstan starting to assemble and eventually produce some industrial goods like vehicles), the range of cooperative products will broaden, potentially moving up the value chain (e.g., energy technologies, machinery, and automotive components).

Nevertheless, some studies urge caution regarding the future trajectory of China–Kazakhstan economic cooperation. Dukeyev [

11] and Wang [

12] express concerns that political instability in Central Asia and enduring public wariness could pose risks. They note that while Central Asian governments seek to leverage BRI to counterbalance Russian influence, there is still a deficit of mutual understanding and trust between local populations and Chinese entities. In Kazakhstan, segments of society have harbored suspicions toward the influx of Chinese companies and workers, fueled by historical fears and misinformation. Although the Kazakh government has taken steps to promote and protect foreign partnerships, a lack of broad public support could constrain future projects. Additionally, Russia’s traditional dominance in the region’s politics and security means that Kazakhstan must carefully navigate its cooperation with China so as not to trigger geopolitical frictions. These insights suggest that while the economic logic for cooperation is strong, soft factors like public perception and geopolitical considerations must be managed to ensure long-term success.

In summary, the theoretical context for China–Kazakhstan cooperation under the BRI highlights a balance of opportunities and challenges. On one hand, the partnership is driven by clear complementary interests, strategic alignment of national initiatives, and the promise of mutual economic gains (especially through industrial cooperation such as automotive manufacturing). On the other hand, sustaining this partnership requires careful attention to political sensitivities and the inclusion of measures to build trust and equitable benefits. This study focuses on the automotive industry as a key area where these dynamics play out, offering a concrete window into how high-level BRI visions translate into sectoral cooperation on the ground.

This study employs a qualitative content analysis approach to investigate the development of China–Kazakhstan automotive industry cooperation. Content analysis is a research method for systematically and objectively analyzing textual or visual information, allowing researchers to interpret themes, patterns, and meanings within documents and communications. A qualitative content analysis (as opposed to quantitative coding alone) is well-suited to our inquiry because much of the relevant data—such as government agreements, policy statements, and media reports—are unstructured text that convey narrative and strategic context rather than easily quantifiable data. By qualitatively examining these texts, we can extract insights into the policy logic, industrial positioning, strategic intents, and evolving cooperation models that define Sino-Kazakh collaboration in the automotive sector.

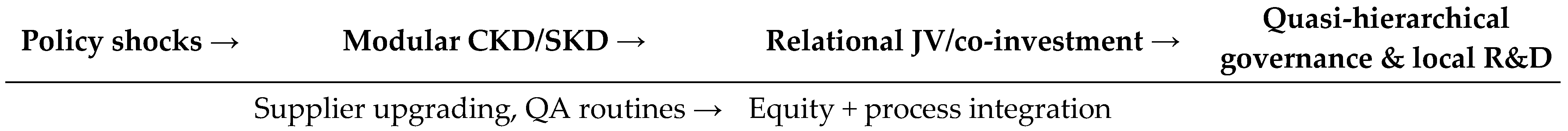

Building on Gereffi–Humphrey–Sturgeon [

13], the cooperation has progressed from modular (CKD/SKD import assembly with codified specs), to relational (co-investment, co-design of processes, localized supplier development), and into emerging hierarchical/captive elements (equity control, in-house standards, plant-level R&D). Key triggers: (i) policy instruments (public procurement localization, recycling incentives), (ii) equity ties (JAC/CMC–Allur, Chery–Astana Motors industrial park), (iii) capability formation (paint/weld shops; component lines).

Figure 1 illustrates the development of governance in Sino–Kazakh automotive cooperation under the BRI. The data sources for analysis include (1) official bilateral documents (e.g., agreements, memoranda of understanding, and joint statements between the Chinese and Kazakh governments related to industrial and automotive cooperation), (2) policy speeches and press releases by government officials in both countries (especially those highlighting BRI cooperation and automotive projects), (3) industry news and media reports from Chinese and Kazakh outlets (reporting on automotive market developments, project milestones, public opinion, etc.), and (4) company press releases and project descriptions (particularly from Chinese automakers involved in Kazakhstan). These sources were collected from public domains, e.g., government websites, news archives, industry publications, and academic repositories, ensuring that all data is from open, published sources (no confidential or private data).

In conducting the content analysis, we followed a structured process: first, we gathered a corpus of relevant documents from 2013 (when BRI was announced) to 2024. We then performed a thematic coding, identifying recurring themes such as “technology transfer,” “investment model,” “localization,” “policy support,” “market expansion,” and “challenges.” Through iterative reading and coding, we distilled the material into coherent categories corresponding to the phases of cooperation and key issues. This method allows us to summarize clear and systematic cooperation themes from a large volume of text, understand the discourse and strategic intent of the stakeholders, and reveal the evolution of cooperation pathways over time.

Methodological Transparency and Source Credibility Protocol

We followed a pre-specified protocol for qualitative content analysis and source triangulation.

- (1)

Collection: e harvested policy documents (laws, decrees, inter-governmental MoUs), firm-level releases, industry association statistics (AKAB), OICA/CEIC production series, and major media with primary data citations.

- (2)

Eligibility: Sources were retained if they (i) reported a verifiable statistic or policy text, (ii) were produced by an official body/industry association, or (iii) were corroborated by ≥2 independent outlets.

- (3)

Credibility Rating: We rated each item High (official statistics or inter-governmental texts), Medium (industry associations and OEM releases), and Exploratory (journalism/analyst notes with indirect data).

- (4)

Cross-Verification: Every quantitative claim in Results was cross-checked against at least one independent statistical series (AKAB/OICA/World Bank/UNESCO UIS/WIPO).

- (5)

Coding & Audit: Two coders independently applied a structured codebook (policy instruments; GVC mode; capability upgrading; localization; risk). Cohen’s κ for code agreement was 0.79; disagreements were resolved by consensus.

- (6)

Reproducibility: A full bibliography with URLs and access dates accompanies the Data Reliability Matrix (

Table 1). Where publicly queryable portals are used (WIPO IP Statistics Data Center; World Bank/UNESCO UIS), we specify indicator names and query endpoints to enable replication.

- (7)

Limitations: Pairwise patent co-inventorship at the CN–KZ level is sparse and sometimes masked in aggregates; we therefore (i) report KZ PCT activity/time-trends directly and (ii) use the presence/absence of CN–KZ co-inventions (from WIPO’s “International co-inventions—inventor country pairs”) as a qualitative phase marker.

Table 1.

Data Reliability Matrix.

Table 1.

Data Reliability Matrix.

| Claim Used in the Paper | Evidence Type | Primary Source(s) | Cross-Check | Credibility |

|---|

| JAC/CMC acquired 51% of Allur Group (May 2019) | Deal announcement | Gasgoo Autonews; Forbes KZ digest | People’s Daily (RU) review feature | High |

| 2019 decree: state procurement restricted to locally produced cars (CT-KZ) for 2 years | Gov’t decree summary | Newsline; Axar | AKAB notes (public procurement exclusion list) | High |

| Domestic share breached ≈59% in 2019 (sales) | AKAB market stats (reported via media) | Astana Times (December 2019) | AKAB “market share >50% in Oct” note | Medium–High |

| Home-produced share reached ~70% by 2024 | Official newswire citing plant outputs | Kazinform (July 2024) | Plant output breakdown | High |

| BYD launched retail only in Jan–Feb 2025 (after delays in 2024) | OEM/distributor releases; press | Astana Motors; Astana Group; Kolesa.kz; Kursiv | — | High |

| KZ GERD (R&D expenditure) 0.145% of GDP (2023) | World Bank/UNESCO UIS | World Bank WDI (GB.XPD.RSDV.GD.ZS) | UIS country portal | High |

| China GERD 2.56% (2022) | World Bank/UNESCO UIS | World Bank WDI | UIS fact sheet | High |

| KZ PCT international applications 23 (2023); national-phase entries 16 | WIPO country profile (last updated 05/2025) | WIPO KZ statistical profile (PDF) | — | High |

| Chinese brands’ share surged in 2023–2024 | Association & trade analytics | Focus2Move 2023/2024; AKAB news; BestSellingCarsBlog (Jan’23) | Messe Frankfurt Central Asia brief | Medium |

To illustrate how different types of sources contributed to our analysis,

Table 2 outlines the main categories of materials and their analytical purpose.

Using this qualitative content analysis approach, our study triangulates information from the above sources to build a comprehensive narrative. By systematically comparing Chinese and Kazakh perspectives in the texts, we ensure a balanced understanding of the cooperation. The methodology allows us to capture not only what cooperation has occurred (facts and figures), but also how and why it has unfolded in this manner—including the motivations of stakeholders and the context of decisions. This is crucial for drawing nuanced conclusions and making informed suggestions for the future.

3. Results

3.1. China’s Automotive Industry: Policy, Export Trends, and Internationalization

China’s automotive industry has evolved into the world’s largest, but it now stands at a crossroads where further growth depends on qualitative improvements and international expansion [

35,

36]. Over the past decades, Chinese government policy has strongly influenced the sector’s development—from joint venture requirements that facilitated technology transfer in the early years [

37], to recent initiatives encouraging innovation and global competitiveness [

38]. After years of rapid expansion, Chinese auto industry policy entered a new stage emphasizing the creation of globally competitive automotive groups and the upgrading of the industrial value chain [

39]. Key policy documents (like “Made in China 2025” and industry-specific plans) call for Chinese automakers to build strong international brands, improve quality and after-sales service, and leverage platforms such as the BRI to deepen international cooperation [

40]. The underlying goal is to move Chinese auto manufacturing from a volume-centric growth model to one focused on innovation, brand value, and higher value-added segments of production.

Recent global events have had a profound impact on China’s automotive export trends. The geopolitical fallout from the Russia–Ukraine conflict since 2022, coupled with the trade tensions between China and Western countries, inadvertently opened new markets for Chinese automakers. With Western and Japanese firms scaling back or exiting the Russian market due to sanctions and political pressure, Chinese brands seized the opportunity to fill the void. As a result, Chinese car exports to Russia surged, and by extension, Chinese vehicles have made greater inroads into Central Asian markets that have close economic ties with Russia [

41,

42]. Analysts attribute this rapid expansion not only to external factors but also to China’s long-term logistical strategy: the development of transcontinental rail routes and trade corridors under the BRI has reduced transportation barriers, making it easier to ship Chinese cars westward [

43]. In essence, China’s westward logistics capabilities (e.g., rail links through Kazakhstan) and the sudden increase in demand in Russia/Central Asia created a perfect window for Chinese automakers to gain market share in those regions.

Despite these successes, Chinese automakers face significant challenges in their internationalization drive. Industry studies show that while China leads globally in sheer production volume, its automakers’ presence in mature markets remains limited and they are vulnerable to global economic fluctuations [

44]. The COVID-19 pandemic, semiconductor supply shortages, and rising protectionism have all affected automotive supply chains and sales, prompting Chinese firms to consider how to maintain stable growth amid “deglobalization” trends [

45]. Researchers argue that Chinese auto companies must adapt by improving their resilience and focusing on strategic markets where they have competitive advantages [

12]. In the long run, the only viable path for China’s auto industry is further internationalization—essentially “going global”—because the domestic market’s growth is slowing and global integration is necessary for technological and innovative leapfrogging.

However, multiple sources diagnose several internal weaknesses that Chinese automakers need to overcome to succeed abroad. These include a relatively low level of indigenous R&D and innovation (many Chinese firms still rely on technology from foreign partners for core components), weaker global brand recognition and brand equity for most Chinese marques, and underdeveloped international distribution and after-sales service networks. Additionally, Chinese car companies historically focused on cost leadership, which sometimes came at the expense of quality perception and overseas customer trust. If Chinese cars are to capture significant market share in competitive markets, they must invest in enhancing product quality, safety, and design to meet higher consumer expectations, as well as establish reliable after-sales support overseas [

46]. Studies comparing China’s automotive development to that of established auto-producing nations (like the USA, Germany, Japan, or South Korea) suggest that having strong independent innovation capability and a positive brand image are crucial for export success. For example, South Korean automakers in the past two decades significantly improved their global standing by focusing on quality and design, a trajectory Chinese firms seek to emulate [

47].

In response to these challenges, Chinese policymakers and companies have taken steps such as increasing investment in electric vehicles (EVs) and new energy vehicle technologies, where they can potentially leapfrog established players, and using diplomatic channels (like BRI forums) to secure market access agreements [

48].

As the global automotive industry shifts toward electric vehicles (EVs), the China–Kazakhstan partnership is increasingly framing its future through the lens of electrification. China is at the forefront of the EV revolution—every tenth car on Chinese roads is now electric, and the country accounted for about 40% of worldwide electric car exports in 2024 [

49]. Facing protectionist pressures in Western markets, Chinese EV manufacturers have pivoted to emerging economies, including Central Asia [

50]. In Kazakhstan, demand for EVs, though nascent, is growing rapidly, buoyed by supportive policies such as a zero import customs duty on electric cars through end-2025. Chinese automakers have quickly filled this niche: in 2023 Kazakhstan imported roughly 6875 electric cars from China, and by 2024 sales of Chinese EVs in Kazakhstan had surged by a factor of 36 year-on-year. This remarkable growth reflects a convergence of interests—China’s push to export green technology aligns with Kazakhstan’s efforts to modernize and decarbonize its transportation sector.

It is conceivable that Kazakhstan may follow—indeed, discussions are underway to establish a local EV manufacturing plant in Kazakhstan [

51]. Such a move would cement the country’s role in the EV supply chain, enabling technology transfer in battery assembly, charging infrastructure, and software for electric drivetrains. From China’s perspective, cultivating EV assembly hubs abroad helps absorb domestic overcapacity and advances the goals of Made in China 2025 by upgrading overseas production to high-tech outputs. For Kazakhstan, embracing EV manufacturing and infrastructure supports its green economy transition and mitigates chronic urban air pollution, while also creating skilled jobs in a future-oriented industry.

That said, significant challenges must be managed to realize this EV-driven cooperation. One concern is infrastructure: Kazakhstan’s electric grid and charging network remain underdeveloped relative to the anticipated growth in EV usage. Lawmakers have noted that power grid capacity and charging standards will need upgrades to accommodate the influx of EVs. Chinese companies are beginning to address this by tailoring EV models to local conditions—for instance, JAC Motors and others have adapted electric models for extreme temperatures and rough roads in Kazakhstan—and by engaging in dialogue on charging protocol compatibility. Furthermore, policy coordination is key. The Belt and Road framework provides a platform for joint initiatives on green infrastructure: both countries can collaborate on installing charging stations along BRI transit routes and share best practices in EV regulation. Overall, the electric vehicle transition is becoming a focal point of China–Kazakhstan industrial collaboration. By jointly investing in EV technology and infrastructure now, the two partners are not only responding to global automotive trends but also shaping a more sustainable and high-tech foundation for their future cooperation [

52].

The BRI itself is seen as a vehicle to facilitate auto exports: Chinese-built infrastructure (ports, railroads, logistics parks) along the BRI can specifically support the export of heavy goods like vehicles [

53]. Moreover, China often engages in policy coordination with BRI countries to harmonize standards and regulations, for instance, aligning automotive technical standards, or negotiating reduced tariffs within free trade agreements or regional unions, which can smooth the entry of Chinese vehicles into those markets [

54].

Kazakhstan, as a member of the EAEU, imposes common external tariffs and standards influenced historically by Russian regulations. Chinese automakers entering Kazakhstan benefit from bilateral and multilateral agreements that China has pursued to improve trade flows with the EAEU [

55]. This cooperative policy environment, combined with Kazakhstan’s receptiveness, has made Kazakhstan one of the first countries where Chinese automakers have moved beyond just exporting into actually assembling and manufacturing vehicles locally [

56]. The subsequent sections of this paper will detail how one Chinese company, in particular JAC Motors, pioneered this process, and how other Chinese brands are following suit, supported by both home-country policy pushes and host-country incentives.

3.2. Kazakhstan’s Automotive Industry Development and Market

Kazakhstan’s automotive industry is a relatively young sector that has become a focal point of the country’s industrial policy in the last decade. Historically, Kazakhstan’s automobile market was supplied by imports, mainly second-hand vehicles or new vehicles from Russia, Europe, Japan, and South Korea, with very limited local assembly [

57]. In the 2000s, initial steps toward local assembly were taken through foreign direct investment: for example, Kazakhstan’s Asia Auto plant (in Ust-Kamenogorsk) assembled vehicles under license for brands like Škoda, Chevrolet, Lada, and Kia, among others. By 2010, several such assembly projects were producing small volumes, often from semi-knocked-down (SKD) kits. While modest, these early efforts proved the concept that Kazakhstan could host automotive assembly operations, given its market size and regional location [

58].

The government of Kazakhstan has actively supported the automotive sector as part of its broader industrialization agenda. Policies include tax breaks for local assembly, preferential procurement rules, and industry development programs such as the Roadmap 2019–2024 [

59]. A significant policy measure was the 2019 decree banning government agencies from purchasing imported cars, requiring them instead to buy domestically assembled vehicles. This effectively created a guaranteed demand for locally produced cars, encouraging further investment in local assembly [

60]. The legal basis was rooted in Kazakhstan’s Law on Public Procurement and related regulations on protecting the domestic market [

61]. As a result, being recognized as a “Kazakhstan-made” automobile became highly advantageous, prompting foreign manufacturers to localize production to qualify for public tenders. The partnership with JAC Motors (as discussed later) and similar deals with other Chinese automakers can be partly understood in this context by producing within Kazakhstan, these companies attain the status of domestic manufacturers, unlocking both government contracts and certain tax/customs incentives.

Kazakhstan’s market has been on a steady growth trajectory. By around 2012–2013, annual new car sales in Kazakhstan had grown sharply (a trend interrupted by an economic downturn in 2015–2016 due to falling oil prices and currency devaluation, but later recovering). The COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 did not hamper Kazakhstan’s automotive sales as severely as expected; in fact, local industry data indicated continued growth in production and sales through 2020 and 2021 [

62]. The share of locally assembled vehicles in Kazakhstan’s new car market has increased dramatically in recent years, reaching about 60% by 2018 and roughly 66% (two-thirds) by 2020. This means the majority of new cars sold in Kazakhstan are now assembled domestically—a stunning rise from a decade prior, and a testament to successful industrial policy and partnerships [

63]. During the same period, Kazakhstan’s automotive manufacturing output grew over 50%, becoming one of the leading segments of its machinery manufacturing industry [

64]. The output of vehicles not only caters to local demand but has also begun to be exported to neighboring countries, marking Kazakhstan’s entry as an exporter (albeit on a small scale so far) in the automotive domain.

The growth of Kazakhstan’s auto industry can be attributed to several factors: stable consumer demand supported by a growing middle class, government incentives as mentioned, and crucially, foreign partnerships bringing in technology and capital. Apart from Chinese firms, notable players include Russian automaker AvtoVAZ (Lada) which has long dominated budget segments, and more recently, partnerships with companies like Hyundai (which opened a plant in Almaty in 2019 for completely knocked down assembly (CKD). South Korean Hyundai models and Russian Lada models consistently rank among the top sellers in Kazakhstan, indicating that Kazakh consumers are open to non-Western brands that can offer reliability or affordability. Chinese brands were not significantly present in Kazakhstan until the mid-2010s; their subsequent rise (detailed in

Section 4) was facilitated by the trail blazed by JAC Motors and the conducive environment created by Kazakhstan’s policies.

Kazakh experts view automotive industry development as strategically important. Ilasheva and Beknazarov emphasize that the automotive sector can play a substantial role in Kazakhstan’s economy by fostering related industries and contributing to GDP growth. They argue that having a local automotive manufacturing base is part of being a diversified modern economy, and its absence historically was a gap Kazakhstan needed to fill. Furthermore, analyses like Smatildayeva et al. [

65] have discussed Kazakhstan’s integration into global value chains (GVCs) in the automotive industry, using Kostanay region (where a major assembly cluster is located) as a case study. Their findings suggest that participation in automotive GVCs (through partnerships with foreign automakers) can yield macroeconomic benefits and greater stability for Kazakhstan by embedding its economy into international production networks. This integration is aligned with Kazakhstan’s goals under the BRI—not just to be a transit corridor but also to develop local production and value-added capabilities.

3.3. Quasi-Experimental Estimate of Localization Effects

Design: We estimate a two-period DiD on the share of home-produced vehicles in new sales using Kazakhstan as treated and a “low-exposure” Central Asian control that had no passenger-car localization before 2024 (Kyrgyzstan/Tajikistan; assembly activity in KG started only in 2024–2025). Treatment = post-policy era (2019–2024) with procurement/localization pushes; Control remains ~0% localized over the same horizon [

66,

67].

Inputs: KZ pre-policy baseline (2015) ≈ 17%; post (2019) ≈ ~59%; post-late (2024) ≈ ~70%. Controls: ≈0% throughout 2015–2023.

Back-of-the-envelope effect: Using 2015 as baseline and 2024 as post, the DiD point estimate is on the order of +50–55 percentage points (ΔKZ ≈ +53 pp vs. ΔControl ≈ 0 pp).

Caveats: Parallel trends are plausible given zero localization in controls, but 2022–2023 shocks (re-exports to Russia, supply chain disruptions) could bias magnitude.

In summary, Kazakhstan’s automotive industry has quickly moved from near non-existence to a growing manufacturing sector with regional significance. The government’s protective and promotional measures have nurtured local assembly, and foreign partnerships (especially with Chinese firms in recent years) have provided the technology and know-how needed for expansion. With strong domestic demand, supportive policies, and external investment, Kazakhstan is poised to continue this upward trajectory. The following sections will delve into how China–Kazakhstan cooperation has specifically propelled this industry, structuring the analysis around the phases of collaboration and technological deepening.

4. Discussion

The evolution of the China–Kazakhstan automotive industry partnership can be delineated into three major phases, each characterized by a distinct mode of cooperation and level of technology transfer.

Table 3 demonstrates: Phase 1—Export and Assembly (2014–2017), Phase 2—Technology Partnership (2018–2021), and Phase 3—Localization and Joint Ventures (2022–2024). This periodization emerges from our analysis of shifts in strategy, policy support, and the nature of industrial involvement over time. In this section, we discuss each phase in detail, highlighting key events, achievements, and challenges.

4.1. Phase 1: Export and Assembly (2014–2017)

Phase 1 marks the beginning of substantive automotive cooperation, initiated under the high-level political agreement of capacity cooperation between China and Kazakhstan. In late 2014, Chinese Premier Li Keqiang visited Kazakhstan and for the first time proposed integrating China’s industrial capacity with Kazakhstan’s resources under the BRI framework. Among the areas of focus was the automotive sector—the idea was to combine Chinese technology and manufacturing know-how with Kazakhstan’s desire to develop its own industry, thereby carrying out joint infrastructure and industrial projects. This political commitment was formalized in 2015 through two Memorandum of Understanding, which included specific provisions for cooperation in automobile manufacturing. These agreements can be seen as foundational, setting the stage for corporate-level deals and projects.

On the corporate front, a landmark partnership was forged between Anhui Jianghuai Automobile Co. (JAC Motors) and Kazakhstan’s Allur Group (the leading domestic automotive holding company). In 2014, JAC Motors responded to China’s policy call and signed a product assembly and distribution agreement with Allur Group. This agreement allowed Allur to begin assembling semi-knocked-down kits of JAC vehicles in Kazakhstan and sell them domestically [

68]. Initial models assembled included JAC’s S3 and S5 compact SUVs, N-series light trucks, and even a small batch of electric vehicles (the iEV6S). The inclusion of new energy vehicles at this early stage was notable, signaling an intent to introduce advanced vehicle types to the Kazakh market. Shortly after, JAC and Allur deepened their collaboration by signing a “JAC Product Assembly Authorization Agreement” in Beijing. This second agreement was more comprehensive: it granted Allur the license to assemble JAC’s full model lineup in Kazakhstan, and it explicitly aimed to promote the localization of production and eventual export of Kazakh-assembled JAC cars to Russia and other neighboring countries. In essence, by covering nearly all JAC models, this agreement transformed the partnership into an exclusive strategic alliance for the region. The cooperation up to this point was still primarily assembly-oriented, but it set a precedent for deeper integration.

Initially, Chinese automobiles entered Kazakhstan simply as imports—either fully built units or as SKD kits for basic assembly. This market-oriented entry mode was straightforward, involving standard sales contracts and requiring minimal coordination aside from logistics and marketing. However, as soon as the assembly agreements took effect, JAC Motors expanded the scope of locally assembled products and started establishing a more permanent presence in the market. During 2015–2016, assembly operations ramped up in Kostanay (a key industrial city in northern Kazakhstan where Allur’s facilities are located), and JAC invested in training and equipping Allur’s assembly line. Chinese technicians provided on-site guidance, and technology transfer began in areas such as assembly techniques, quality control, and workforce training. The benefits of this technology transfer were multi-fold, aligning with theories of international technology licensing and spillovers [

69]. For Kazakhstan, acquiring assembly know-how and gradually learning to produce automotive parts meant jump-starting an industry without having to reinvent the wheel—it could leverage China’s mature automotive technology to build an industrial base. For JAC Motors, helping establish a local manufacturing operation provided a foothold in the region and improved its competitiveness: with local assembly, JAC could avoid high import tariffs (as Kazakhstan applies significant duties on imported vehicles) and reduce transportation costs, allowing JAC vehicles to be priced more competitively in Kazakhstan. Moreover, local production enhances a company’s brand image and acceptance, since consumers and officials see it as contributing to the local economy (this is particularly important given the Kazakh government’s support for local manufacturing).

The early results of Phase 1 were encouraging. By 2015, JAC Motors—a newcomer to Kazakhstan—climbed into the top 15 best-selling automotive brands in the country. This was a remarkable achievement considering the entrenched position of brands like Lada, Toyota, Hyundai, and others. It demonstrated that with the right mix of affordability and local presence, a Chinese brand could gain market share even in a competitive environment. In 2016, the cooperation took a leap forward with the launch of the Kostanay JAC Automobile Plant, a joint venture factory that was part of a list of 32 priority industrial projects between the two countries. In fact, this project was highlighted by both governments as the only automotive industry project among those strategic initiatives, underscoring its political and economic significance. The Kostanay plant started SKD production (basic assembly from imported kits) of JAC vehicles, but with a roadmap for increasing localization. As an immediate impact, in 2016 JAC’s sales (now counted as “domestic production” in Kazakhstan) surged by 500% compared to 2015. The JAC S3 SUV even won Kazakhstan’s “People’s Brand” award that year, a sign of its popularity and acceptance by Kazakh consumers. By 2017, Allur and JAC assembled 765 vehicles in Kazakhstan, and for the first time, vehicles produced in Kazakhstan were exported to neighboring markets (with about 200 units sent to Central Asian countries in 2017). This milestone of exporting regionally fulfilled one of the cooperation’s early goals and was widely reported in local media as Kazakhstan’s entry into automobile exporting. Also, in 2017–2018, JAC’s brand rose to become the 4th most popular in the Kazakh auto market, indicating sustained performance.

From a GVC perspective, the governance of the Sino-Kazakh automotive venture in Phase 1 transitioned from a purely market-based relationship to what can be described as “modular/relational” governance [

70]. In the very initial stage (around 2014–2015), when JAC was mostly exporting CBUs or SKD kits, the interactions were market-based—each transaction was arms-length, guided by prices and contracts, with low asset specificity. As soon as local assembly commenced and technology transfer activities started, the nature of coordination changed. The relationship became more relational, meaning it required closer communication, mutual trust, and longer-term commitment. Kazakhstan’s government contributed by providing a supportive policy environment (tax breaks, inclusion in industrialization programs, etc.) and by treating the JAC-Allur venture as a domestic producer (thereby qualifying it for government procurements). JAC contributed not just capital and kits but also managerial expertise and technical training. This interdependence and exchange of tacit knowledge (e.g., technical know-how and training) are hallmarks of relational governance in GVCs. In Phase 1, however, the governance had not yet reached a hierarchical form; JAC did not own the Kazakh enterprise, and decision-making was shared or negotiated. This balance was beneficial in the early stage as it allowed flexibility and adaptation, both sides were learning how to work together and how to operate in a new market context.

It is also worth noting the competitive landscape during Phase 1. Kazakhstan’s market was, and remains, heavily influenced by Russian and other foreign brands. Russian-made Lada cars, due to their low price and historical presence, were consistently top sellers (from 2015 to 2019 Lada was among the top three brands annually, capturing, for instance, about 23% market share in 2018). Western and Japanese brands like Toyota, Chevrolet, and Hyundai also had significant market share, often assembled in Kazakhstan or imported from Russia. For JAC (and Chinese brands generally) to succeed, they needed to prove themselves against these established players on quality, price, and service. The early success of JAC was thus not just a product of government support but also of competitive positioning: JAC vehicles, particularly the crossovers like S3, offered a modern design and features at a price point attractive to middle-class Kazakh buyers, undercutting many Western/Japanese models while being more modern than the cheapest Russian models. The assembly in Kazakhstan also meant JAC could market their cars as “Made in Kazakhstan with Chinese technology,” which had a certain appeal in terms of national pride and reliability (given China’s growing reputation in manufacturing).

In summary, Phase 1 established the proof of concept for China–Kazakhstan cooperation in automotives. The joint efforts resulted in Kazakhstan’s first meaningful production and export of vehicles and demonstrated win–win outcomes: Kazakhstan nurtured a nascent auto industry, and China (via JAC) gained a new market and regional production base. As one Chinese media outlet described it, this was a “capacity cooperation achieving a win–win situation” for both countries. The stage was set for deeper cooperation, which indeed followed in the next phase.

4.2. Phase 2: Technology Partnership (2018–2021)

Phase 2 of the cooperation saw a transition from basic assembly to a deeper technology partnership and capacity expansion. By around 2018, the initial assembly project had matured, and both sides were looking to elevate the cooperation. A key development at the outset of this phase was the Chinese partners increasing their stake and control in the Kazakh venture. In 2019, JAC Motors, together with China National Machinery Import and Export Corporation (CMC), undertook a strategic investment to acquire a majority share (51%) of Allur Group. This move effectively transformed the governance model of the cooperation to a lead-firm (hierarchical) model, where JAC (and its Chinese ally) assumed the role of controlling shareholders. By becoming the major stakeholder in Allur, JAC gained strong supervisory control and could more directly steer the operations, decisions, and future investments of the Kazakh entity. For the Kazakh side, selling a stake in Allur was likely seen as a trade-off to secure greater capital infusion and long-term commitment from the Chinese side, as well as to solidify JAC’s identity as a domestic producer (since now the producer was partially Chinese-owned but legally local).

This joint venture restructuring coincided with policy shifts and market trends that underscored the mutual benefits of deeper integration. As mentioned, in 2019 the Kazakh government’s ban on state procurement of imported vehicles came into force. With JAC-Allur now classified as a domestic manufacturer, its vehicles became eligible for government and public sector fleet purchases—a significant boost in potential demand (Kazakhstan’s government and state-owned enterprises are major vehicle buyers, especially for SUVs, pickups, and other utilitarian vehicles suitable for the country’s terrain). JAC’s acquisition of Allur thus not only consolidated its local presence but also ensured it could leverage these policy privileges.

From 2019 through 2021, the China–Kazakhstan automotive partnership deepened in qualitative ways. First, technology transfer entered a phase of “deep integration.” The Allur/JAC operations began moving from SKD to CKD assembly, meaning a greater portion of work (welding, painting, assembly of completely disassembled parts) was performed in Kazakhstan as opposed to just final assembly. Chinese engineers trained Kazakh technicians in more advanced manufacturing processes like body welding and automotive painting—processes that require significant skill and are crucial for raising the local content of vehicles. By the end of Phase 2, the localization rate (the percentage of parts by value sourced or made locally) of vehicles assembled in Kazakhstan had reportedly increased to about 15%. While still modest, this indicates progress beyond merely bolting together kits; local suppliers for certain components (e.g., tires, batteries, glass, small plastic parts) may have started contributing. There were also efforts to develop parts production: for instance, plans were announced to begin producing some automotive components like multimedia systems and car seats in Kazakhstan by 2025, showing a forward-looking strategy to broaden the industrial base. These plans fall in line with moving the cooperation up the value chain, aiming for Kazakhstan to eventually manufacture a significant share of auto parts domestically [

71].

Second, industrial capacity and output saw significant growth. According to industry reports, by 2020 Kazakhstan’s annual vehicle production crossed the 50,000-unit mark for the first time. Locally produced vehicles (including all brands assembled in Kazakhstan) accounted for roughly two-thirds of all new cars sold in the country, which was a dramatic increase from perhaps only one-third earlier in the decade. Specifically, the share of the automotive industry in Kazakhstan’s machinery manufacturing sector rose from 26.3% in 2019 to 33.4% by 2021, reflecting how auto manufacturing became a leading driver of industrial growth [

72]. Even the global pandemic in 2020 did not halt this progress—Kazakhstan’s auto sales and production continued to expand while many other industries contracted. Chinese media highlighted Kazakhstan’s “vast automobile market and rapid development” despite COVID-19, attributing it partly to the timely capacity cooperation projects that met pent-up demand for new vehicles.

Third, new Chinese entrants and partnerships emerged. While JAC was the pioneer, other Chinese automotive companies took notice of Kazakhstan’s potential and the success of the JAC-Allur model. In April 2021, Great Wall Motors’ SUV brand Haval officially entered the Kazakh market, setting up dealerships and planning local assembly. In December 2021, Geely Auto (another major Chinese manufacturer) began sales in Kazakhstan, similarly eyeing local assembly opportunities. Then in 2022, Kazakhstan’s largest automotive holding Astana Motors signed memoranda with Chery Automobile, Changan Automobile, and Great Wall Motor to produce their models in Kazakhstan. Astana Motors even announced a project to build a new multi-brand automobile plant in Almaty’s Industrial Zone, slated to produce Chery, Changan, and Haval vehicles with an annual capacity in the tens of thousands and start production by 2025. These developments signaled that the China–Kazakhstan auto cooperation was no longer confined to a single company (JAC) but had grown into a broader trend of Chinese automakers partnering with local firms to localize production. The driving force for the Chinese companies was clear: Kazakhstan represented both a growing market in itself and a manufacturing springboard into the Russia-led EAEU common market (which, besides Kazakhstan, includes Russia, Belarus, Armenia, and Kyrgyzstan). By producing in Kazakhstan, Chinese firms could potentially export cars duty-free to Russia and other EAEU countries, circumventing some of the import barriers they face if exporting directly from China.

From Kazakhstan’s viewpoint, the influx of multiple Chinese automakers was a welcome development that could accelerate the country’s quest to become an automotive manufacturing hub in Central Asia. Local authorities pushed for deeper localization: for example, they encouraged the expansion of full-cycle assembly (CKD) and the development of supplier parks (for parts like engines, batteries, etc.). By late 2020, Kazakhstan’s leadership openly championed the idea of establishing automotive clusters and parts production bases in various regions. The presence of several Chinese firms increased competition and technology flow, which could benefit Kazakhstan through knowledge spillover and better consumer choice. It also fit into Kazakhstan’s “Bright Road” program of attracting foreign investment into manufacturing and creating jobs. Recent geopolitical realignments have accelerated Kazakhstan’s bid to become a regional automotive assembly hub. Redirected supply chains and sanctions-resistant strategies incentivize Chinese, Korean, and Russian automakers to localize partial assembly (e.g., semi-knock-down) within Kazakhstan. The Astana Motors Manufacturing Kazakhstan plant in Almaty, capable of assembling three Chinese brands with an annual capacity of 120,000 units, exemplifies this shift. Meanwhile, ten component-manufacturing projects are underway in Kostanai and Almaty to support localization. This industrial clustering offers sustainable value beyond transit alone and strengthens Kazakhstan’s integration into Eurasian production networks.

Crucially, Phase 2 also saw Kazakhstan starting to export vehicles in notable quantities, predominantly those produced by the joint ventures with Chinese companies. Since JAC’s acquisition of Allur, the Kazakh-produced JAC vehicles began reaching other markets: in 2020, over 8000 cars assembled in Kazakhstan were exported (more than double the roughly 2600 exported in 2019). These exports, valued at ~55.9 billion Kazakh tenge, went to neighboring countries in Central Asia. Essentially all of Kazakhstan’s vehicle exports were coming out of the Allur (Golden Steppe) factory, underscoring the importance of the Chinese partnership in enabling Kazakhstan not only to meet domestic demand but also to become a minor exporter. Although the volumes are still small on a global scale, the growth rate is impressive and symbolically important—Kazakhstan had gone from 0 exports to thousands in a short span, marking its entry into the regional automotive supply chain.

A significant contextual factor in this phase was the strategic necessity underscored by global politics. The souring of China’s relations with the U.S. and Europe, and Russia’s pivot toward China amidst Western sanctions, placed Central Asia in a more central position for China’s economic strategy. Scholars and commentators pointed out that for Kazakhstan to reduce its economic dependence on Russia and assert a more balanced foreign policy, it was prudent to deepen ties with China and other partners. Conversely, China, needing stable markets and routes to Europe that bypass potentially unfriendly territories, found in Kazakhstan a reliable partner to host part of its industrial chain. This confluence of interests provided strong political backing throughout Phase 2. It is no surprise that even during the pandemic, high-level virtual meetings and statements reiterated the commitment to keep the BRI projects moving. Both governments framed the continued industrial cooperation as a way to overcome new global challenges and to prepare for the post-pandemic economic recovery.

Table 4 below illustrates the structural transformation that occurred in China–Kazakhstan automotive cooperation between 2016 and 2024. This period, spanning the later stages of Phase 2 and the entirety of Phase 3, marks a significant progression from basic assembly operations toward localized CKD manufacturing capacity and enhanced technological capabilities. Notably, the reliance on imported technology gradually gave way to improved domestic R&D competencies, while market outreach expanded from domestic consumption to exports across the EAEU. These developments correspond with the objectives of Phase 3, which focused on joint ventures, supply chain localization, and international competitiveness.

Although BYD is a leading NEV producer globally, its official Kazakhstan entry was delayed: plans shifted from 2024 to retail launch in Jan–Feb 2025, with first showrooms opening in Almaty/Astana. Over 2023–2024, this timing disadvantage coincided with: (i) limited fast-charging coverage beyond major cities and regulatory uncertainty over grid readiness; (ii) homologation/price positioning under EAEU technical regs; and (iii) early mover advantages of other Chinese brands (Chery, Haval, JAC/Jetour) already embedded via Astana Motors and Allur plants/sales networks. These factors plausibly depressed BYD’s initial market penetration despite favorable national policies for localization and EVs [

73,

74,

75,

76,

77,

78,

79].

Summarizing Phase 2, the China–Kazakhstan automotive partnership became more institutionalized and multifaceted. It moved beyond a single-project focus to involve multiple actors and an ecosystem of cooperation (assemblies, supplier development, exports). The transfer of technology deepened, the scale of production grew, and bilateral investment ties strengthened (with Chinese capital now embedded in Kazakhstan’s auto industry). By the end of 2021, one could assert that Kazakhstan had established itself as an emerging automotive producer, thanks in large part to Chinese partnerships. The stage was now set for the current phase, where localization and innovation are in greater focus.

4.3. Phase 3: Localization and Joint Ventures (2022–2024)

Phase 3 represents the current state of cooperation (as of 2022–2024) and is characterized by efforts to consolidate gains, further increase localization, and explore joint ventures in higher value activities such as research and development (R&D). This phase is ongoing, but we can identify its early characteristics and trajectory.

A hallmark event was the Xi’an Summit in May 2023, the first China–Central Asia leaders’ summit, which highlighted the success of Sino-Kazakh cooperation and charted a vision for its future. In conjunction with that summit and other diplomatic exchanges (including mutual state visits), official statements on both sides emphasized the intention to elevate economic cooperation to a new level. Chinese government communications (e.g., through the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Xinhua News Agency) underscored that China and Central Asian countries will pursue “even closer economic cooperation under the BRI framework” to navigate the complex international environment. For Kazakhstan specifically, it was noted that there will be deeper integration of China’s BRI with Kazakhstan’s “Bright Road” strategy, expanding cooperation in fields including automobile manufacturing among others. In other words, the automotive sector was explicitly recognized as a continuing pillar of bilateral cooperation, and plans were made to further support it.

President of Kazakhstan Tokayev, at the Xi’an Summit and in other forums in 2023, praised the achievements of China–Kazakhstan automotive cooperation. He highlighted that numerous Chinese automobile production projects are successfully operating in various regions of Kazakhstan, and he encouraged Chinese companies to establish automotive industry clusters in the country. This encouragement is backed by assurances that the Kazakh government will protect investors’ interests and create all necessary conditions for them. Essentially, Kazakhstan signaled not only a welcoming stance but also an active courtship of more Chinese investment in advanced stages of the automotive value chain—for instance, manufacturing of parts like engines or batteries, or setting up R&D centers and joint design bureaus. The idea of “automotive industry clusters” suggests a move toward geographic concentrations of suppliers and assemblers, perhaps similar to what one sees in more developed automotive economies, scaled to Kazakhstan’s context [

79].

On the market side, by 2024 the presence of Chinese automotive brands in Kazakhstan has reached a new high. Nine Chinese automotive brands are reported to be selling or planning production in Kazakhstan, including well-known ones such as Geely, Chery, Changan, Haval (Great Wall), FAW, JAC, as well as sub-brands like Exeed (Chery’s premium line) and Jetour (another Chery sub-brand), and even FAW’s iconic Hongqi (Red Flag) brand which targets the high-end segment. This diversity of brands means Chinese automakers are covering all segments of the market—from budget cars and commercial vehicles to luxury SUVs. A key development was the signing of a memorandum between Kazakhstan’s Astana Motors LLP and China’s Chery International Co., Ltd. in December 2023, initiating the establishment of a joint automotive industrial park in the Almaty industrial zone [

80]. In the same year, JAC Motors (the pioneer) has continued to perform strongly; for instance, JAC sold over a certain threshold of vehicles (the exact figure was truncated in our source, but it implies a record number) in Kazakhstan, reflecting steady growth. Furthermore, Chinese automotive manufacturer JAC significantly expanded its production footprint in Kazakhstan, with more than 35,000 vehicles manufactured in the first five months of 2024, representing over 62% of total national automobile output [

81]. These industrial achievements coincide with strengthened political ties, underscored by the state visit of President Xi Jinping to Kazakhstan in July 2024. During this visit, both sides reaffirmed their commitment to deepen industrial integration and advance Belt and Road cooperation, with the automotive sector highlighted as a key area of future growth [

82].

Kazakhstan’s automotive market itself has continued to expand, and Chinese automakers are capturing a growing share. By early 2023, Chinese brands collectively accounted for an estimated 15–20% of new car sales in Kazakhstan (based on industry reports), a share that has likely risen with the introduction of new models and brands. The trend indicates that consumers are increasingly accepting Chinese cars, which are often priced competitively and now offer modern features and designs comparable to other global brands. The establishment of local assembly for more brands is also improving consumer confidence (since local assembly typically ensures better availability of spare parts and service, and sometimes even a price advantage).

On the industrial front, Phase 3 has an emphasis on local parts manufacturing and joint ventures in R&D. As noted, plans are underway for local production of certain components: for example, production of car seats and in-vehicle multimedia systems in Almaty is expected by 2025. These are often the first kinds of components to localize because they are less technologically complex than engines or transmissions but still provide significant value-add and jobs. In Kostanay, the site of the original JAC-Allur collaboration, there are discussions about producing engines or EV components in the future, leveraging Chinese expertise.

Moreover, joint R&D projects are on the horizon. Both governments have encouraged moving from simple assembly to co-development of vehicles. This could take the form of adapting Chinese models to Kazakh conditions (like extreme weather, road conditions) via local engineering input, or even developing a Kazakh-branded vehicle platform with Chinese technical support. While these ambitions are just beginning to materialize, they represent the next logical step for the partnership—evolving from manufacturing to innovation. Joint R&D would cement Kazakhstan’s climb up the value chain and integrate its engineers into international automotive design networks, while giving Chinese firms access to local talent and possibly new ideas.

At a policy level, Phase 3 also involves standardization and regulatory alignment. To facilitate the operation of Chinese cars in Kazakhstan and potential export onward, efforts are made to harmonize vehicle standards (safety, emissions, etc.) between China, Kazakhstan, and the EAEU. This is often performed through mutual recognition agreements or adoption of international standards. Simplifying customs procedures, improving logistics (for example, enhancing the efficiency of rail transport of auto parts from China to Kazakhstan), and ensuring the availability of financing (like affordable auto loans or lease options for consumers, possibly through Chinese financial institutions in Kazakhstan) are also part of the ongoing support framework in this phase.

Finally, it is important to acknowledge the challenges that persist or arise in Phase 3. While the cooperation has been lauded as a success by leaders, certain issues need continuous management. Overcapacity in China—if Chinese production outstrips global demand, dumping cheap vehicles in Kazakhstan could hurt local ventures if not managed; thus Chinese firms need to ensure they do not just treat Kazakhstan as an outlet for oversupply but invest in sustainable operations. Competition is intensifying—not only among Chinese brands inter se, but also Western and other Asian automakers are eyeing Kazakhstan (for instance, Russia’s situation has opened it to more Chinese imports, but in Kazakhstan, companies like Lada and Hyundai are responding by updating models or increasing their own local assembly). Workforce development is an ongoing task—training more Kazakh engineers, managers, and technicians to reduce reliance on expatriate Chinese staff. Public perception remains something to nurture: as Chinese involvement deepens, it is crucial that the local population sees tangible benefits (jobs, affordable cars, knowledge transfer) to maintain broad support and avoid any nationalistic backlash against “foreign dominance.” So far, the signs are positive, as evidenced by Tokayev’s strong endorsement, but public outreach (like corporate social responsibility efforts by Chinese firms, local procurement to benefit Kazakh SMEs, etc.) will play a role in sustaining goodwill.

In conclusion, Phase 3 is about solidifying and innovating. The China–Kazakhstan cooperation in automotives has moved beyond the initial assembly success into a phase where the creation of a self-sustaining automotive ecosystem in Kazakhstan is within reach. If successful, Kazakhstan could become a Central Asian automotive manufacturing hub, exporting not only to its neighbors but potentially further, and Chinese automakers will have a firm long-term base in the region. This phase, being current, will be critical to watch in the coming years, as it will determine whether the partnership simply yields short-term outputs or truly transforms into a durable, high-tech collaboration with its own momentum.

Table 5 presents a phased evaluation of the effectiveness of technology transfer throughout the China–Kazakhstan automotive cooperation timeline. During Phase 1 (2014–2016), the collaboration was limited to complete vehicle exports, resulting in minimal localization (<5%) and a workforce composed largely of unskilled labor. In Phase 2 (2016–2019), the shift to licensed production (SKD) led to increased localization (15%), the emergence of skilled workers, and modest process innovations. Finally, Phase 3 (2019–present) witnessed the maturation of the partnership through full-process manufacturing and joint R&D initiatives. This stage saw the localization rate rise to 35%, alongside the formation of engineering teams and enhanced product adaptation capabilities. The table effectively maps the evolution of technical content, transfer modalities, and innovation capacity across the three cooperation stages.

5. Conclusions

The cooperation between China and Kazakhstan in the automobile industry under the Belt and Road Initiative has progressed through three distinct stages, each yielding significant benefits to both parties. In the first phase (2014–2017), the focus was on market entry and assembly, with China (via companies like JAC Motors) supplying vehicles and basic manufacturing technology, and Kazakhstan gaining its first foothold in automobile production. This phase demonstrated the viability of capacity cooperation: Kazakhstan benefited from job creation and the inception of an auto industry, while Chinese firms opened new markets and avoided trade barriers by localizing production. The second phase (2018–2021) deepened the partnership into a technology-driven alliance. Chinese investment and ownership in Kazakhstan’s automotive ventures increased, governance shifted to a more integrated model, and technology transfer intensified—moving Kazakhstan up the value chain from simple assembly to partial localization of parts and components. The auto sector in Kazakhstan grew rapidly in output, and Kazakhstan emerged as a regional exporter of vehicles, showcasing the success of the partnership. The third (ongoing) phase (2022–2024) is characterized by localization and joint ventures aimed at higher value activities. Multiple Chinese automakers are now present, local assembly is becoming full-cycle with an expanding local supplier base, and plans are in motion for joint R&D and the manufacturing of more complex components in Kazakhstan. High-level political support from both Beijing and Astana remains strong, positioning the automotive cooperation as a flagship project of the BRI in Central Asia.

Throughout these stages, the collaboration has been mutually beneficial and aligned with each country’s strategic goals: China has addressed domestic overcapacity and bolstered its automakers’ global reach, while Kazakhstan has accelerated its industrialization, reduced dependence on imports, and moved towards economic diversification. The case exemplifies how BRI partnerships can evolve from simple trade to comprehensive industrial integration. It also illustrates the importance of supportive policies—such as Kazakhstan’s incentives for local manufacturing and China’s promotion of its enterprises “going out”—in achieving a sustainable cooperation framework.

However, to ensure long-term sustainability and to fully realize the potential of this partnership, several steps should be taken going forward. Based on our analysis, we offer the following key recommendations for policymakers and industry stakeholders in both countries:

Accelerate Technology Transfer and Move to Joint R&D: The two sides should transition from technology use to technology creation. This means establishing joint research and development centers or programs where Chinese and Kazakh engineers collaborate on designing new vehicle models or automotive technologies (for instance, electric vehicle components suited for extreme climates). By moving toward joint innovation, Kazakhstan can gradually develop its own engineering capabilities and intellectual property in the automotive field, while Chinese companies can tailor products more closely to regional needs and possibly discover novel solutions (a form of reverse innovation). Joint R&D would also help keep the partnership dynamic and future-oriented.

Develop Local Supply Chains through Industrial Parks: Building on the idea of automotive clusters, we recommend creating a dedicated automotive parts industrial park in Kazakhstan (if possible, near existing assembly plants like in Kostanay or Almaty). Such a park would host parts manufacturers (including those from China as well as Kazakh SMEs) producing components like batteries, tires, glass, electronics, and interiors. China can encourage its auto parts companies to invest in these parks, bringing in expertise in battery technology, electric drivetrains, electronic control systems, etc., which are increasingly important with the global shift to electric vehicles. Kazakhstan, in turn, can offer tax breaks and infrastructure support for park tenants. This would increase the local content of Kazakh-assembled vehicles and create ancillary industry jobs, reinforcing the economic multiplier effects of the automotive sector.

Enhance Training and Human Capital Development: A long-term partnership requires skilled human capital on the Kazakh side. China and Kazakhstan should expand joint training programs—for example, Chinese automakers could establish training academies in Kazakhstan to train local workers in advanced manufacturing, quality control, and auto engineering. Scholarships or exchange programs for Kazakh students in Chinese automotive engineering universities could also be increased. By cultivating a pool of Kazakh technicians and engineers, the dependence on foreign experts will decrease and local innovation will be spurred. This also addresses any local concerns by visibly investing in the people of Kazakhstan.

Utilize Kazakhstan as a Regional Export Hub: The cooperation should not limit itself to the Kazakh domestic market. Both sides should exploit Kazakhstan’s geographic position and trade agreements (like the EAEU) to make it a “regional vehicle and parts export center”. This entails coordinated marketing and distribution efforts to export Kazakh-assembled (or even co-developed) vehicles to neighboring markets: other Central Asian countries, the Caucasus, and even Eastern Europe. Chinese companies can channel exports through Kazakhstan to enjoy EAEU tariff advantages and shorten delivery times using the Trans-Caspian routes or the Eurasian rail corridors. For Kazakhstan, re-exporting adds scale to its production runs and improves the sustainability of factories. Governments can assist by negotiating export financing arrangements or regional auto trade agreements under BRI forums.