Strengthening Active Transportation Through Small Grants

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. United Nations Sustainability

1.2. Environmental

1.3. Economic

1.4. Socio-Cultural

1.5. Solutions Are Multifaceted

1.6. The United States Relies on Advocacy Groups to Promote Bicycling

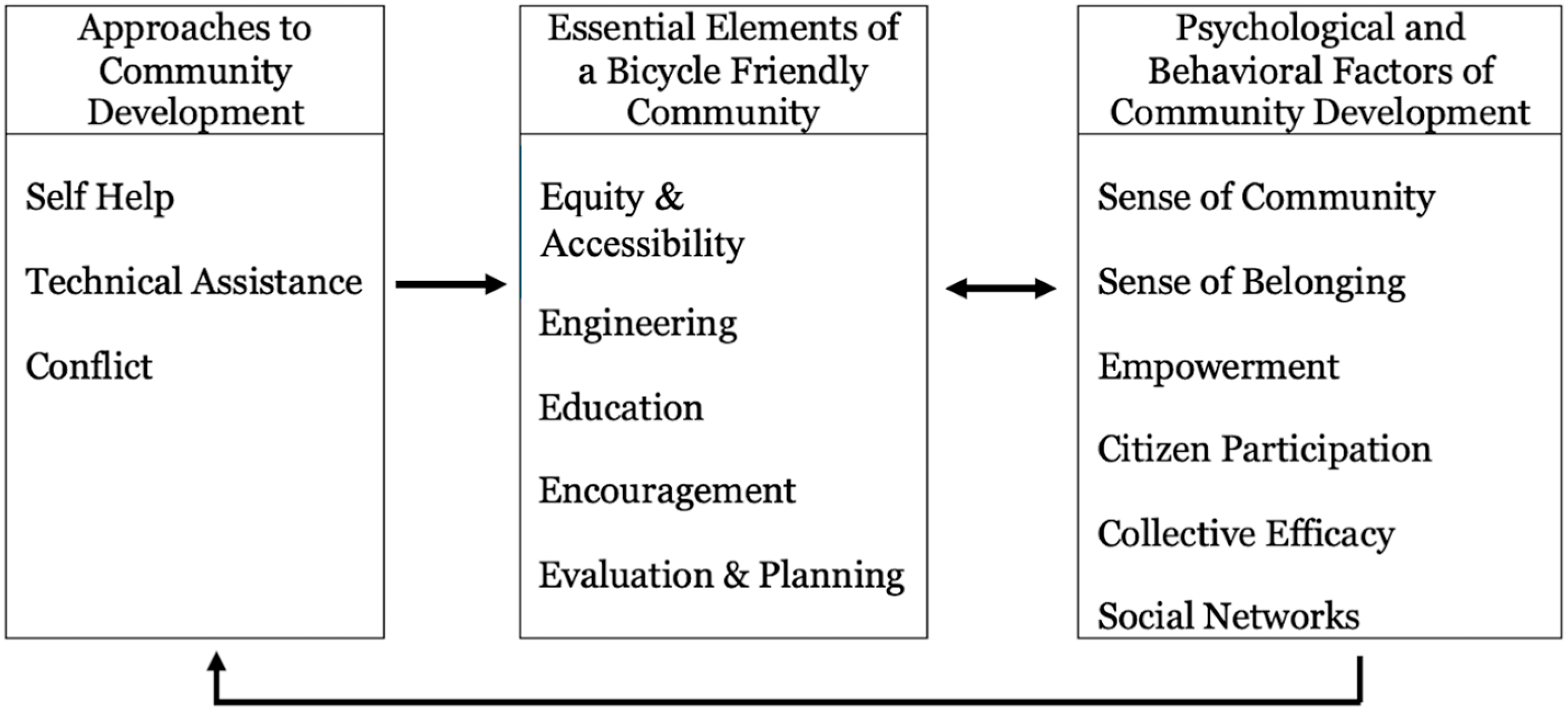

1.7. Bicycle Community Development Framework

1.8. Approaches to Community Development

1.9. Essential Elements of a Bicycle-Friendly Community (5Es)

1.10. Psychological and Behavioral Factors of Community Development

1.11. Purpose Statement

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

2.2. Data Analysis

2.3. Research Process

| Purpose: Evaluate the Outride organization’s efforts to increase bicycling through its Outride Fund recipients. |

| Data Collection: Conducted semi-structured interviews via Zoom with grant recipient organizational leaders following an interpretative phenomenological approach. |

| Data Analysis: Cleaned data, Zoom transcriptions and interviewer notes, before following IPA suggested principles including coding through line-by-line analysis to discover emerging themes. |

| Results: Compared and if appropriate described and themes through the BCDF. |

| Discussion: Explained results in context of Outride’s efforts to increase bicycling in grant funded communities. |

3. Results

3.1. Approaches to Community Development

3.2. Essential Elements of a Bicycle-Friendly Community (5Es)

we will use these grant dollars to build a pump track next to an elementary school and near an existing trail network. Once complete, we’ll start programs like, group rides, bicycle camps, and bicycle training, which should increase use of the track.

the bicycle is a fun, exciting learning tool the kids love and I teach them how to use tools to work on their bike, and the pump track, how to ride safely…so topics like momentum, balance, pedal power, why wear a helmet, and other physics...being comfortable with tools is real important to help them be more self-sufficient.

“that a large group of kids riding respectfully and safely is a rolling billboard promoting bicycling”, while Interviewee #45 commented that “biking is contagious, kids join our program and soon their parents are calling us to see if the brothers and sisters can join; some immigrant mothers that don’t drive have joined our “kids” program; we love it”.

3.3. Psychological and Behavioral Factors of Community Development

mostly in the wintertime when our community needs visitors because summer is already busy…we also groom trails in the winter even when there are no events to attract tourists. Yeah, the tourism people in town appreciate and support us.

we were doing an Earn a Bike program with kids, but couldn’t ride much with these kids. We Zoomed with the kids about how to ride safely and decided to start giving bikes to adult family members, so at least someone could ride with the kids. The result of that was like beyond our possible wildest imagination, and we now ride with those families.(Interviewee #14)

there are significant benefits to these kids given their environment—they get out to natural areas, especially for kids with trauma, the challenge of riding the bike is a benefit- takes time to learn to improve and the self ownership as you must move the pedals, imparts physical and mental skills, analogy for the other aspects of life…if you can get good at cycling then you can get good at other things, build confidence, can be humbling, but you can get over it.

used bicycling in really creative ways, like doing service learning projects with the DOT, where our kids learned about safe streets and urban planning through workshops by local professionals, and then they assessed streets and presented their findings and suggestions to the Community Board and DOT and the suggestions have been approved! We are now on our fourth project with the DOT.

the kids call my class life-tech, because we teach them how to write resumes, present themselves, business, profit and statements and about climate change and how the bicycle can save the world and you as a bike tech can save the world. If you can fix someone’s bike so they don’t need to drive a car, you’re changing the world, you know, oh my God, we can change the world!

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Future Research Recommendations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Outride. Mission Outride. n.d. Available online: https://outridebike.org/aboutus (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Johansson, C.; Lövenheim, B.; Schantz, P.; Wahlgren, L.; Almström, P.; Markstedt, A.; Strömgren, M.; Forsberg, B.; Sommar, J.N. Impacts on air pollution and health by changing commuting from car to bicycle. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 584–585, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.-H.; Chancellor, C. A conceptual framework for integrating bicycle friendliness into community development. Community Dev. 2019, 50, 589–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Tao, L.; Yang, F.; Bao, Y.; Li, C. Promoting green transportation through changing behaviors with low-carbon-travel function of digital maps. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Communciations 2024, 11, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Goal 11: Make Cities Inclusive, Safe, Resilient and Sustainable. United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. 17–20 October 2016. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/cities/ (accessed on 12 October 2024).

- Pucher, J.; Buehler, R. Making cycling irresistible: Lessons from the Netherlands, Denmark and Germany. Transp. Rev. 2008, 28, 495–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorobets, A. Development of bicycle infrastructure for health and sustainability. Lancet 2016, 388, 1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrelja, R.; Rye, T. Decreasing the share of travel by car, Strategies for implementing ‘push’ or ‘pull’ measures in a traditionally car-centric transport and land use planning. Int. J. Sustain. Transp. 2022, 17, 446–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsenkova, S.; Mahalek, D. The impact of planning policies on bicycle-transit integration in calgary. Urban Plan. Transp. Res. 2014, 2, 126–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The White House. Putting America First in International Environmental Agreements. 2025. Available online: https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/01/putting-america-first-in-international-environmental-agreements/ (accessed on 23 February 2025).

- Mrkajic, V.; Vukelic, D.; Mihajlov, A. Reduction of CO2 emission and non-environmental co-benefits of bicycle infrastructure provision: The case of the University of Novi Sad, Serbia. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 49, 232–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Rueda, D.; de Nazelle, A.; Tainio, M.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J. The health risks and benefits of cycling in urban environments compared with car use: Health impact assessment study. BMJ 2011, 343, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, W.; Forsberg, B.; Johansson, C.; Sommar, J.N. Air pollution as a risk factor in health impact assessments of a travel mode shift towards cycling. Glob. Health Action 2018, 11, 1429081-13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravett, N.; Mundaca, L. Assessing the economic benefits of active transport policy pathways: Opportunities from a local perspective. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2021, 11, 100456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishman, E.; Schepers, P.; Kamphuis, C.B.M. Dutch cycling: Quantifying the health and related economic benefits. Am. J. Public Health 2015, 105, e13–e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, J.H. Urban bicycle tourism: Path dependencies and innovation in greater Copenhagen. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1648–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meschik, M. Sustainable cycle tourism along the Danube cycle route in Austria. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2012, 9, 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, B.; Riley, C.; Herrin, J.; Spatz, E.S.; Arora, A.; Kell, K.P.; Welsh, J.; Rula, E.Y.; Krumholz, H.M. Identifying county characteristics associated with resident well-being: A population based study. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0196720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatersleben, B.; Murtagh, N.; White, E. Hoody, goody or buddy? How travel mode affects social perceptions in urban neighbourhoods. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2013, 21, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatersleben, B.; Uzzell, D. Affective appraisals of the daily commute: Comparing perceptions of drivers, cyclists, walkers, and users of public transport. Contemp. Account. Res. 2007, 39, 416–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaJeunesse, S.; Rodríguez, D.A. Mindfulness, time affluence, and journey-based affect: Exploring relationships. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2012, 15, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaire-Gonzalez, D.; de Nazelle, A.; Cole-Hunter, T.; Curto, A.; Rodriguez, D.A.; Mendez, M.A.; Garcia-Aymerich, J.; Basagaña, X.; Ambros, A.; Jerrett, M.; et al. The added benefit of bicycle commuting on the regular amount of physical activity performed. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2015, 49, 842–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzek, M.; Jackowski, J.; Jurecki, R.S.; Szumska, E.M.; Zdanowicz, P.; Żmuda, M. Electric Vehicles—An overview of current Issues—Part 1—Environmental impact, source of energy, recycling, and second life of battery. Energies 2024, 17, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meenar, M.; Flamm, B.; Keenan, K. Mapping the emotional experience of travel to understand cycle-transit user behavior. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Congestion Relief Zone. 2025. Available online: https://congestionreliefzone.mta.info/about (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Piatkowski, D.; Bopp, M. Increasing bicycling for transportation: A systematic review of the literature. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2021, 147, 04021019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Sustainable & Smart Mobility. n.d. Available online: https://transport.ec.europa.eu/eu-mobility-transport-achievements-2019-2024/sustainable-smart-mobility_en (accessed on 28 September 2024).

- Cohen, J. How U.S. Bike Planning Has Changed, State by State Next City. 29 March 2017. Available online: https://nextcity.org/urbanist-news/statewide-bike-plans-new-updating-none (accessed on 15 October 2024).

- Alexander, D. “They’re So Bad”: Donald Trump Promises to Scrap “Dangerous” New York Bike Lanes and “Kill” Congestion Charge. road.cc. 11 February 2025. Available online: https://road.cc/content/news/trump-vows-scrap-dangerous-new-york-bike-lanes-312577 (accessed on 13 March 2025).

- Chen, L.; Chen, C.; Srinivasan, R.; McKnight, C.E.; Ewing, R.; Roe, M. Evaluating the safety effects of bicycle lanes in New York City. Am. J. Public Health 2012, 102, 1120–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanford Braff, C. The Perfect Time to Ride: A History of the League of American Wheelmen; American Bicyclist: Newport, RI, USA, 2007; pp. 18–23. [Google Scholar]

- Guroff, M. American Drivers Have Bicyclists to Thank for a Smooth Ride to Work. Smithsonian. 12 September 2016. Available online: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/travel/american-drivers-thank-bicyclists-180960399/ (accessed on 9 October 2024).

- League of American Bicyclists. Awards Criteria. n.d.a. Available online: https://bikeleague.org/bfa/5-es/ (accessed on 28 February 2025).

- Keener, R. Origins of Unity: How Bikes Belong Shaped Industry Collaboration. PeopleForBikes. 13 August 2024. Available online: https://www.peopleforbikes.org/news/bikes-belong-history (accessed on 22 August 2024).

- People for Bikes. Mission. People for Bikes. n.d. Available online: https://www.peopleforbikes.org/mission (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Fosterling, J. 2024’s Best Places to Bike. PeopleForBikes. 21 June 2024. Available online: https://www.peopleforbikes.org/news/2024-best-places-to-bike (accessed on 22 August 2024).

- Adventure Cycling Associaton. Our Mission. n.d. Available online: https://www.adventurecycling.org/about/mission/ (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- League of American Bicyclists. Equity and Our History. n.d.b. Available online: https://bikeleague.org/about/equity-and-history/ (accessed on 8 December 2024).

- Christenson, J.A. Themes of community development. In Community Development in Perspective; Christenson, J.A., Robinson, J.W., Jr., Eds.; Iowa State University Press: Ames, IA, USA, 1989; pp. 26–47. [Google Scholar]

- Gallardo, R. Information Sheet 2019 (POD-09-15). In Community Economic Development Approaches Technical Report; Mississippi State University: Mississippi State, MS, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J.W., Jr.; Green, G.P. Developing communities. In Introduction to Community Development: Theory, Practices, and Service-Learning; Robinson, J.W., Jr., Green, G.P., Eds.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, S. The Importance of Community. Psychology Today. 18 July 2023. Available online: https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/what-the-wild-things-are/202307/the-importance-of-community (accessed on 3 April 2024).

- McLean, M. “Me Too” Global Movement—What Is the “Me Too” Movement; Global Fund for Women: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2012; Available online: https://www.globalfundforwomen.org/movements/me-too/ (accessed on 28 June 2022).

- Fisher, A.T.; Sonn, C.C. Psychological sense of community in Australia and the challenges of change. J. Community Psychol. 2002, 30, 597–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, D.; Long, D. Neighborhood sense of community and social capital: A multi-level analysis. In Psychological Sense of Community: Research, Applications, and Implications; Fisher, A., Sonn, C., Bishop, B., Eds.; Plenum: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 291–318. [Google Scholar]

- Fulbright-Anderson, K.; Auspos, P. Community Change: Theories, Practice, and Evidence. 2006. Available online: https://www.aspeninstitute.org/publications/community-change-theories-practice-and-evidence/ (accessed on 24 April 2024).

- Vidal, A.C. Reintegrating disadvantaged communities into the fabric of urban life: The role of community development. Hous. Policy Debate 1995, 6, 169–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagerty, B.M.K.; Lynch-Sauer, J.; Patusky, K.L.; Bouwsema, M.; Collier, P. Sense of belonging: A vital mental health concept. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 1992, 6, 172–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagerty, B.M.K.; Williams, R.A.; Coyne, J.C.; Early, M.R. Sense of belonging and indicators of social and psychological functioning. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 1996, 10, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslow, A.H. Motivation and Personality; Addison-Wesley Educational Publishers Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, M.; McLaren, S. Physical activity alone and with others as predictors of sense of belonging and mental health in retirees. Aging Ment. Health 2005, 9, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rappaport, J. Terms of empowerment/exemplars of prevention: Toward a theory for community psychology. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1987, 15, 121–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christens, B.D.; Speer, P.W. Community organizing: Practice, research, and policy implications. Soc. Issues Policy Rev. 2015, 9, 193–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, M.A.; Israel, B.A.; Schulz, A.; Checkoway, B. Further explorations in empowerment theory: An empirical analysis of psychological empowerment. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1992, 20, 707–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maton, K.I. Empowering community settings: Agents of individual development, community betterment, and positive social change. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2008, 41, 4–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohmer, M.L. Citizen participation in neighborhood organizations and its relationship to volunteers’ self-and collective efficacy and sense of community. Soc. Work. Res. 2007, 31, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamble, D.N.; Weil, M.O. Citizen participation. In Encyclopedia of Social Work, 19th ed.; Edwards, R.L., Ed.; National Association of Social Workers: Washington, DC, USA, 1995; Volume 1, pp. 483–494. [Google Scholar]

- Blanchet-Cohen, N. Igniting citizen participation in creating healthy built environments: The role of community organizations. Community Dev. J. 2015, 50, 264–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control; W.H. Freeman and Company: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, B.; Hunt, J. Collective efficacy: Taking action to improve neighborhoods. Natl. Inst. Justice J. 2016, 277, 18–21. Available online: http://nij.gov/journals/277/Pages/collective-efficacy.aspx (accessed on 25 February 2024).

- Barnes, J.A. Class and committees in a Norwegian Island Parish. Hum. Relat. 1954, 7, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, R.M.; Chan, C.D.; Farmer, L.B. Interpretative phenomenological analysis: A contemporary qualitative approach. Couns. Educ. Superv. 2018, 57, 240–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, M.; Larkin, M.; de Visser, R.; Fadden, G. Developing an interpretative phenomenological approach to focus group data. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2010, 7, 99–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.A. Evaluating the contribution of interpretative phenomenological analysis. Health Psychol. Rev. 2011, 5, 9–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.A.; Osborn, M. Interpretative phenomenological analysis as a useful methodology for research on the lived experience of pain. Br. J. Pain 2014, 9, 41–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, J.A. Reflecting on the development of interpretative phenomenological analysis and its contribution to qualitative research in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2004, 1, 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larkin, M.; Watts, S.; Clifton, E. Giving voice and making sense in interpretative phenomenological analysis. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 102–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietkiewicz, I.; Smith, J.A. A practical guide to using Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis in qualitative research psychology. Psychol. J. 2014, 20, 7–183. [Google Scholar]

- Nowell, L.S.; Norris, J.M.; White, D.E.; Moules, N.J. Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthines criteria. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2017, 16, 1609406917733847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooshmand, J.; Hotz, G.; Neilson, V.; Chandler, L. BikeSafe: Evaluating a bicycle safety program for middle school aged children. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2014, 66, 182–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nachman, E.R.; Rodriguez, D.A. Evaluating the effects of a class-room-based bicycle education intervention on bicycle activity, self-efficacy, personal safety, knowledge, and mode choice. Front. Sustain. Cities 2023, 5, 1098473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richmond, S.A.; Zhang, Y.J.; Stover, A.; Howard, A.; Macarthur, C. Prevention of bicycle-related injuries in children and youth: A systematic review of bicycle skills training interventions. Inj. Prev. J. Int. Soc. Child Adolesc. Inj. Prev. 2014, 20, 191–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, W.E.; Ferenchak, N.N. Why cities with bicycling rates are safer for all road users. J. Transp. Health 2019, 13, 100539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Abdel-Aty, M.; Lee, J.; Lee, C. Developing crash modification functions to assess safety effects of adding bike lanes for urban arterials with different roadway and socio-economic characteristics. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2015, 74, 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, M.A.; Reynolds, C.C.; Winters, M.; Cripton, P.A.; Shen, H.; Chipman, M.L.; Cusimano, M.D.; Babul, S.; Brubacher, J.R.; Friedman, S.M.; et al. Comparing the effects of infrastructure on bicycling injury at intersections and non-intersections using a case–crossover design. Inj. Prev. 2013, 19, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, C.A.; Newton, W.N.; LaRochelle, L.; Daly, C.A. National incidence and trends of bicycle injury. J. Orthop. Res. Off. Publ. Orthop. Res. Soc. 2023, 41, 1464–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, A. From civil rights to black lives matter protest, expert aldon morris explains how social justice movements succeed. Scientific American. 3 February 2021. Available online: https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/from-civil-rights-to-black-lives-matter1/ (accessed on 24 April 2024).

- Elliott, L.D.; Bopp, M. Success and Challenges of Community Bicycle Advocacy Organizations in Reaching Underserved Populations. Community Health Equity Res. Policy 2023, 45, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willis, D.; Manaugh, K.; El-Geneidy, A. Cycling under influence: Summarizing the influence of attitudes, habits, social environments and perceptions on cycling for transportation. Int. J. Sustain. Transp. 2015, 9, 565–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, C. Beyond the Bike; Identity and Belonging of Free Cycles Members. Masters Thesis, University of Montana, Missoula, MT, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Clanton, T.; Chancellor, C.; Pinckney, H.; Balidemaj, V. Examining Youth bicycle programming through the Empowerment- Based Youth Development Model. J. Youth Dev. 2023, 18, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Approach | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Self-Help | Focuses on assets Builds community capacity Strengthens networks | Lengthy Complex Assumes potential and motivation exists |

| Technical Assistance | Provides expert know-how Solves technical issues | Can generate dependency Top-down Short-term time horizon |

| Conflict | Spurs creativity Redistributes power and resources | Requires efficient manager Could make things worse |

| Equity & Accessibility | Ensuring that tangible efforts exist to ensure equitable access and correct for historical disparities and systemic inequities across each of the other 4 E’s. |

| Engineering | The physical environment is the key determinant in whether people bike. Infrastructure includes networks of safe places to ride, maintenance of facilities, and bike parking. |

| Education | Providing instruction on skill development and motorists’ and cyclists’ rights and responsibilities on the road increases rider safety and confidence. |

| Encouragement | Providing opportunities and incentives to ride including signage, maps, commuter challenges, bicycle-themed celebrations, such as participation in National Bike to Work Day. |

| Evaluation & Planning | Develop a comprehensive bicycle master plan in combination with dedicated funding, citizen support, and ideally a dedicated Bicycle Program Coordinator and Bicycle Advisory Committee. |

| Sense of Community | Sociopsychological concepts such as networks, shared interests, and standards contribute to developing an individual’s sense of community [44,45]. Communities are connected by similar attitudes and feelings, and a stronger sense of community increases the likelihood of involvement in community affairs [46,47]. |

| Sense of belonging | Sense of belonging is characterized by feeling valued and “fitting in” with individuals, groups, or environments, and the desire to strengthen these relationships [48,49]. Considered a basic human need it significantly impacts mental and physical health, well-being, and quality of life [50,51]. People with a strong sense of belonging demonstrate higher involvement levels (psychologically, socially, spiritually, or physically), emphasize the importance of their involvement, and develop a foundation for emotional and behavioral responses. Notably, this sense can be tied to an environment, not necessarily to people or organizations [48]. |

| Empowerment | Empowerment involves individuals and groups, particularly those who are under-resourced or oppressed, gaining greater control over their lives and well-being through participation in relevant sociopolitical systems [52,53,54]. Empowered individuals are more capable of acquiring knowledge and resources to enhance their quality of life and reduce marginalization [55]. This process can foster a stronger sense of community and has been identified as a predictor of civic engagement [45]. |

| Citizen participation | Community involvement in decision-making enhances members’ capacities and results in positive changes [56,57]. This participation has proven particularly effective in gaining support and minimizing conflict for infrastructure development projects [58]. |

| Collective efficacy | Collective efficacy is a group’s shared belief in its ability to organize, plan, and execute actions to achieve specific goals [59]. It represents what group members are willing to do to improve their community [60]. This concept appears to be a natural outcome of empowered individuals who possess a strong sense of community and belonging. |

| Social networks | Social networks, as defined by, consist of points (people/groups) and lines (interactions) [61]. A well-functioning bicycle community organization’s social network would feature diverse points and lines, indicating collaborative efforts and social capital. To achieve bicycle-related infrastructure and policy projects, an organization’s network might need to include influential individuals, often elected officials. |

| Theme | Frequency | Percentage (%) * |

|---|---|---|

| Youth-focused | 54 | 82% |

| Bicycling education | 40 | 61% |

| Bikes as a tool for life lessons | 25 | 38% |

| Rider development mountain bike/leagues | 25 | 38% |

| Kids on bikes | 15 | 23% |

| Mentoring | 12 | 18% |

| Infrastructure development | 20 | 30% |

| Community-focused riding | 14 | 21% |

| Bicycle advocacy | 13 | 20% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chancellor, C.; Romans, T.S.; Clanton, T.; Rhodes, T.; Park, S. Strengthening Active Transportation Through Small Grants. Future Transp. 2025, 5, 84. https://doi.org/10.3390/futuretransp5030084

Chancellor C, Romans TS, Clanton T, Rhodes T, Park S. Strengthening Active Transportation Through Small Grants. Future Transportation. 2025; 5(3):84. https://doi.org/10.3390/futuretransp5030084

Chicago/Turabian StyleChancellor, Charles, Trevor S. Romans, Thomas Clanton, Tiffany Rhodes, and Sunwoo Park. 2025. "Strengthening Active Transportation Through Small Grants" Future Transportation 5, no. 3: 84. https://doi.org/10.3390/futuretransp5030084

APA StyleChancellor, C., Romans, T. S., Clanton, T., Rhodes, T., & Park, S. (2025). Strengthening Active Transportation Through Small Grants. Future Transportation, 5(3), 84. https://doi.org/10.3390/futuretransp5030084