1. Introduction

Urban cycling and bike-sharing systems have become increasingly prominent in cities worldwide, providing an alternative mode of transportation that addresses challenges such as traffic congestion, air pollution, and declining physical activity [

1,

2]. Bike-sharing programs offer a flexible and affordable means of mobility, allowing individuals to rent bicycles for short periods. These systems have been integrated into the broader urban transport infrastructure, complementing public transit and contributing to the development of more sustainable urban environments [

2,

3]. The rise of urban cycling and bike-sharing is part of a larger shift towards sustainable, smart mobility policies aimed at reducing car dependency and promoting active mobility (e.g., [

4]).

Research indicates that bike-sharing can enhance urban connectivity by bridging gaps in the public transport network, particularly in areas underserved by traditional transit systems [

5,

6]. Additionally, cycling contributes to public health by encouraging physical activity and reducing exposure to air pollution associated with motorized vehicles [

7]. For instance, one review found that cycling to school helped children increase their overall levels of physical activity while also improving their cycling skills, thus potentially contributing to the development of lifelong physical activity habits [

8].

However, the success of urban cycling or bike-sharing systems depends on a range of factors, including urban density, socio-economic characteristics of users, and the availability of cycling infrastructure [

9,

10]. Studies have shown that bike-sharing usage tends to be higher in densely populated areas and among certain demographic groups, such as younger, more affluent individuals [

11]. Moreover, the benefits of bike-sharing are contingent upon equitable access to bicycles and cycling infrastructure across different urban areas [

5]. Understanding these dynamics is critical for designing effective policies to promote urban cycling and enhance the sustainability of urban transport systems.

One factor, in particular, that is worthy of continued exploration concerns the laws and regulations that may surround cycling, especially as it relates to so-called mandatory helmet laws (MHLs). Though helmets are a clearly effective safety measure for cyclists, MHLs may often disturb existing routines or patterns of urban cycling or bike share usage, presenting challenges for cities seeking to implement smart or sustainable mobility strategies. It is against this background that the following study takes place. In particular, the following study explores how Prague’s proposed MHL [

12]—which was put forth in 2023 and eventually did not pass—could potentially influence private and shared cycling behaviors. To achieve this, we conducted a survey of urban cyclists in Prague to assess their current cycling habits and how they expect those habits to change should an MHL come into place.

Moving forward, this paper progresses in four main steps. First, we will expand on the benefits and challenges of MHLs, thus providing deeper insight into the complexities of such regulations and the context of our study. Second, we will present the general background of cycling in Prague and the methodology of the current study. Third, we will put forward the main results from our survey and, in the end, propose potential implications for research and policy.

2. Mandatory Helmet Laws (MHLs) and Cycling Behavior

The literature on MHL and helmet use presents a complex landscape of safety benefits, behavioral impacts, and public health implications. Helmets are widely recognized for their effectiveness in reducing head injuries among cyclists. A systematic review by Olivier and Creighton [

13] found that helmet use significantly decreases the risk of head injuries by 51% and fatal injuries by 65%, and these results are generally supported by more recent reviews as well [

14]. Likewise, an older systematic review by Macpherson and Spinks [

15] focusing on mandatory helmet laws suggests that such legislation has a protective effect against head injuries and does not seem to reduce the number of cyclists. These findings support the argument for MHL as a means to enhance cyclist safety. However, further studies on the impact of MHLs on cycling behaviors muddy this picture. Clarke [

16] highlights that while MHLs may improve safety, they often lead to a reduction in cycling rates. Similarly, a study from Australia shows a decline in the number of cyclists following the introduction of MHL, suggesting that mandatory helmet policies can deter people from cycling due to various factors [

17]. Indeed, there are numerous psychosocial factors influencing helmet use. Factors such as helmet aesthetics or cost, convenience, prior experiences, parental attitudes, and group norms play significant roles in individuals’ decisions to wear helmets [

18,

19]. For instance, parents have reported that the availability and cost of suitable helmets, as well as the need to buy specific helmets for specific sports (e.g., baseball, ski, etc.), are important limitations. Elsewhere, the perception of helmets as inconvenient or unfashionable often outweighs the recognized safety benefits, a dynamic that may be further exacerbated by the casual, spontaneous nature of bike-sharing. There is also a significant gendered component to these factors, with girls and women regularly found to adopt or encourage helmet use at higher rates [

19]. As such, Valero-Mora and colleagues [

20] concluded that laws alone may not be sufficient to ensure compliance without adequate awareness campaigns providing information about the law and encouraging riders to wear helmets.

The uptake of bike helmets is further complicated in urban environments where bike-sharing programs present additional challenges to associated legislation. Research in New York and Seattle reveals that bike share users are less likely to wear helmets compared to private bicycle users [

21,

22], while one systematic review identifies an “unhelmeted” rate amongst bike share users varying between 36.0 and 88.9% in the retained studies [

23]. This lower rate of helmet use among bike-share users complicates the implementation of MHL, as it could potentially discourage the spontaneous use of shared bicycles, which are integral to sustainable or smart mobility strategies. Elsewhere, further studies and policy analyses examine the legislative context of MHL and its enforcement, exploring how such laws influence urban mobility patterns and cycling behaviors [

24]. Beyond the actual law or policy, enforcement and associated social norms are crucial components. For instance, though helmets are mandatory in Argentina, only 8.5% of the population actually regularly wear a helmet—a stark contrast from Norway, where helmet use is not mandatory and yet uptake is nearly 60% [

18]. As such, information about usage patterns and attitudes in a specific context, such as Prague, is critical to the implementation of MHLs or other safety promotion measures.

3. Background

Urban cycling in Prague has transformed from a non-existent mode of transport to being perceived as one of the main building blocks of Prague’s Active Mobility Strategy, which sets the goal modal split of cycling to be 3.5% on average throughout the year [

25], therefore aiming to almost double cycling rates in the city (cf. [

26]). Historically, Prague’s infrastructure was dominated by car-centric designs with no to limited space for cyclists. However, recent years marked a shift towards integrating cycling into urban mobility plans, driven by growing environmental concerns, technological advancements, and the global climate crisis.

Despite these advancements, the proposal of a mandatory helmet law (MHL) in 2023 for all adults riding a bicycle in the Czech Republic ignited a debate on its potential impacts on urban cycling. Proponents argue that MHL would enhance cyclist safety by reducing head injuries [

12], while critics contend that such legislation could discourage cycling, counteracting the progress made in promoting sustainable transport [

27]. The arguments in favor of implementing the MHL in the Czech Republic primarily revolved around perceived safety benefits. Senator Zuzana Ožanová, who proposed the law, argued that helmets should be mandatory for all cyclists, including adults, to prevent head injuries and “improve police accident statistics” [

12]. She also highlighted that bicycles from the law’s point of view are not only mechanical bikes but also e-bikes and e-scooters, where the speed is high and therefore the risk of accidents is significant [

27]. Similar safety-based arguments have been used in other countries. In neighboring Slovakia, an MHL was introduced in 2009 for cyclists outside of cities, with proponents citing the vulnerability of the head and the need for protection [

28]. In Australia, since the 1970s, the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons (RACS) has pushed for helmet laws as a major road safety measure [

29].

Against this background, the following research examines the potential effects of MHL on cycling behavior, looking deeper into differences between privately owned and shared bicycles, and evaluates its implications for Prague’s climate commitments, especially as it relates to the usage of sustainable mobility options. By analyzing survey data from urban cyclists and reviewing the relevant literature, the study aims to provide insights into the complex relationship between helmet legislation, cycling rates, and sustainability goals, offering a possible perspective on the future of urban mobility in Prague.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Instrument

An online, Likert-scale survey was designed based on existing studies in the area of helmet use and helmet legislation (e.g., [

18,

30]). The survey was divided into four broad parts:

Section 1 filtered for adult age, bicycle usage, and residence in Prague.

Section 2 focused on transportation behavior and asked about the regularity of using own or shared bicycles for transport around Prague and wearing a helmet on those two types of bicycles.

Section 3 captured attitudes related to the proposed MHL in Prague, including participants’ agreement with the proposed law and questions related to their potential mobility behaviors should the law come into effect. And

Section 4 asked for demographic characteristics such as age, gender, and education level. Furthermore, all participants provided informed consent to participate in the survey, and beyond the general demographic characteristics, no personal identifying information was recorded.

4.2. Data Collection

A non-representative, purposive sample of urban cyclists using private bicycles, shared bicycles, or both was targeted. To reach these groups, the questionnaire was spread on relevant, Prague-focused online urban cycling and bike-sharing. These included Facebook groups dedicated to bike-sharing, cycling, or urbanism in Prague; a Discord server dedicated to local bike-share users; an online urban cycling news site; and local Strava cycling groups. All data was collected during the first week of April 2024.

Using this approach, the survey received a total of 506 responses. However, after applying controls based on the filter questions, 448 responses were deemed usable for the final analysis. Male respondents (n = 343) comprised 77% of the sample, while female respondents (n = 105) accounted for 23%. The median age of the entire sample was 32, with a mean of 33.34. Respondents ranged in age from 18 to 72 years. On average, male respondents were 34.55 years old, whereas female respondents had an average age of 29.39 years. Regarding educational attainment, 66.96% (n = 300) of respondents held higher professional or university education, while 33.04% (n = 148) had a high school diploma or lower. In terms of employment status, 45.98% (n = 206) were employed full-time, 21.43% (n = 96) were self-employed, 18.3% (n = 82) were employed part-time, and 5.8% (n = 26) were unemployed.

4.3. Data Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using Jamovi 2.5.3 software. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize respondents’ cycling behaviors, helmet use, and attitudes toward the proposed mandatory helmet law (MHL).

To assess differences in helmet usage between private and shared bicycle users, an independent samples t-test was performed, with Welch’s t-test applied in cases of unequal variances. Chi-square tests for independence were used to examine associations between helmet use and demographic factors, such as biological sex and education level.

Further chi-square tests were conducted to analyze relationships between opinions on the MHL and demographic variables, as well as to evaluate the potential impact of the proposed law on cycling frequency for both private and shared bicycle users. Effect sizes were calculated using Cramer’s V to assess the strength of associations where applicable.

5. Results

5.1. Cycling Behavior

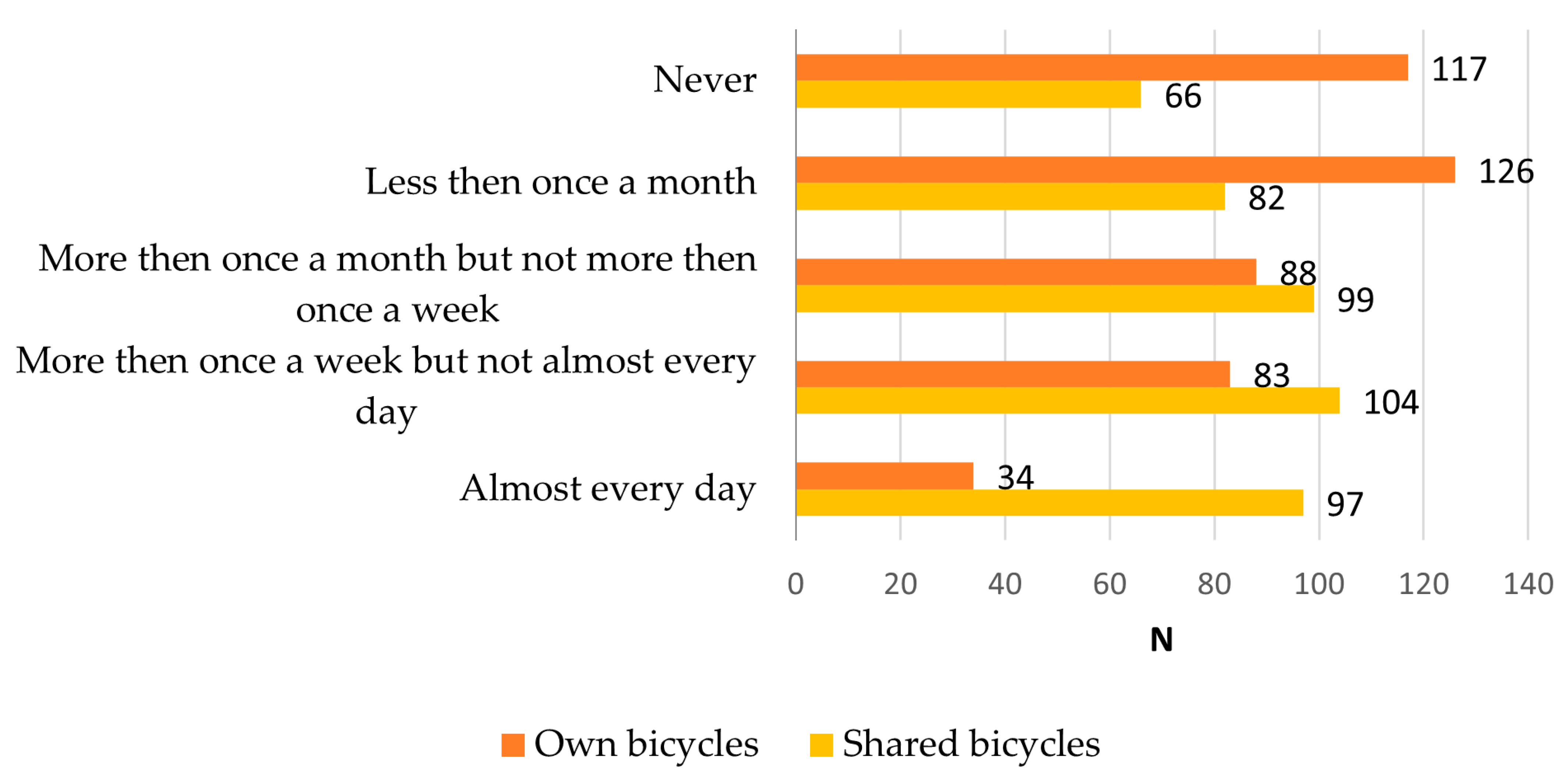

The data indicate that 21.7% (n = 97) of respondents use their own bicycle for transportation in Prague almost every day. A total of 67% (n = 300) of respondents report using their own bicycles at least once a month, while 14.7% (n = 66) of the respondents report never having used their own bicycle in Prague.

As for using shared bicycles for urban transportation, a minority of the survey participants, 7.6% (N = 34), report employing shared bicycles in Prague every day. A total of 26.1% (N = 117) respondents do not employ shared bicycles, and 45.8% (n = 205) of the respondents report using a shared bicycle in Prague at least once a month. The full, detailed distribution of cycling behavior in Prague is presented in

Figure 1.

5.2. Current Helmet Use in Prague

The survey data reveal diverse attitudes towards helmet use among urban cyclists in Prague, with notable differences between users of privately owned and shared bicycles. Nearly 75% of private bicycle riders reported always or mostly wearing a helmet, whereas 62.3% of respondents indicated they have never worn a helmet when using a shared bicycle. Only 1.8% of respondents stated that they always wear a helmet while riding a shared bike. Full results on helmet usage are presented in

Figure 2.

Filtering for users who use exclusively either private or shared bicycles, the difference between “only own bicycle users” and “only shared bicycle users” was significant; t(141) = −6.72, p < 0.001; t(141) = −6.72, p < 0.001; t(141) = −6.72, p < 0.001. Due to unequal variances (p < 0.05 on Levene’s test), Welch’s t-test also confirmed the result; t(29.4) = −4.63, p < 0.001; t(29.4) = −4.63, p < 0.001; t(29.4) = −4.63, p < 0.001.

Neither biological sex nor education levels were found to be statistically significant predictors of helmet use, except in the case of education-levels amongst own bicycle users. Chi-square tests examined the relationship between biological sex and helmet-wearing behavior on both personal and shared bicycles. No significant associations were found for either, χ2(3, N = 116) = 0.575, p = 0.902 for personal bicycles and χ2(4, N = 448) = 5.07, p = 0.280 for shared bicycles. While males reported slightly higher helmet use on both, the differences were not statistically significant. However, education level was significantly associated with helmet use on personal bicycles, χ2(3, N = 116) = 9.85, p = 0.020, with higher rates of consistent helmet use among those with a high school education or lower (87.5%) compared to university-educated individuals (80.3%). For shared bicycles, no significant relationship was found, χ2(2, N = 65) = 0.727, p = 0.695, as most respondents rarely wore helmets regardless of education level.

5.3. Agreement with Proposed MHL

Respondents were further asked for their opinions on the proposed law, providing responses on a six-point scale, where one represents strong disagreement and six represents strong agreement with the proposed regulation. Overall, 60.5% of total respondents indicated that they disagreed or strongly disagreed with the proposed law, compared to 16.8% who agreed or strongly agreed.

Broken down by biological sex, male respondents were more likely to strongly oppose the regulation (48.4%) compared to female respondents (18.6%). Conversely, agreement with the law (scores of 5 and 6) was slightly higher among females (12.8% and 15.1%, respectively) than males (6.5% for both categories). A chi-square test for independence indicated a significant association between biological sex and opinions on the helmet law, χ2(5, N = 334) = 36.2, p < 0.001. These results suggest that attitudes toward mandatory helmet laws differ by biological sex, with males showing stronger opposition and females demonstrating relatively greater support.

5.4. Potential Impact of Proposed MHL on Ridership

A chi-square test of independence was conducted to examine the relationship between the frequency of using one’s own bicycle and whether individuals would expect to ride their own bicycle less if mandatory helmet laws (MHLs) were introduced. The test revealed a significant association, χ2(4,N = 448) = 46.2, p < 0.001, with a medium effect size (Cramer′s V = 0.321). Overall, 19.9% of respondents indicated they would ride their own bicycle less, highlighting the potential impact of an MHL on this subset of users.

The influence of a potential MHL was much stronger on the subset of users using shared bicycles, as 63.6% of respondents indicated they would ride shared bicycles less if an MHL were to be implemented. Furthermore, as above, a chi-square test of independence was conducted to assess the relationship between the frequency of using shared bicycles and whether individuals would ride shared bicycles less if MHL were introduced. The test showed a significant association, χ2(4,N = 448) = 66.8, p < 0.001, with a medium-to-large effect size (Cramer′s V = 0.386; Cramer’s\V = 0.386; Cramer′s V = 0.386).

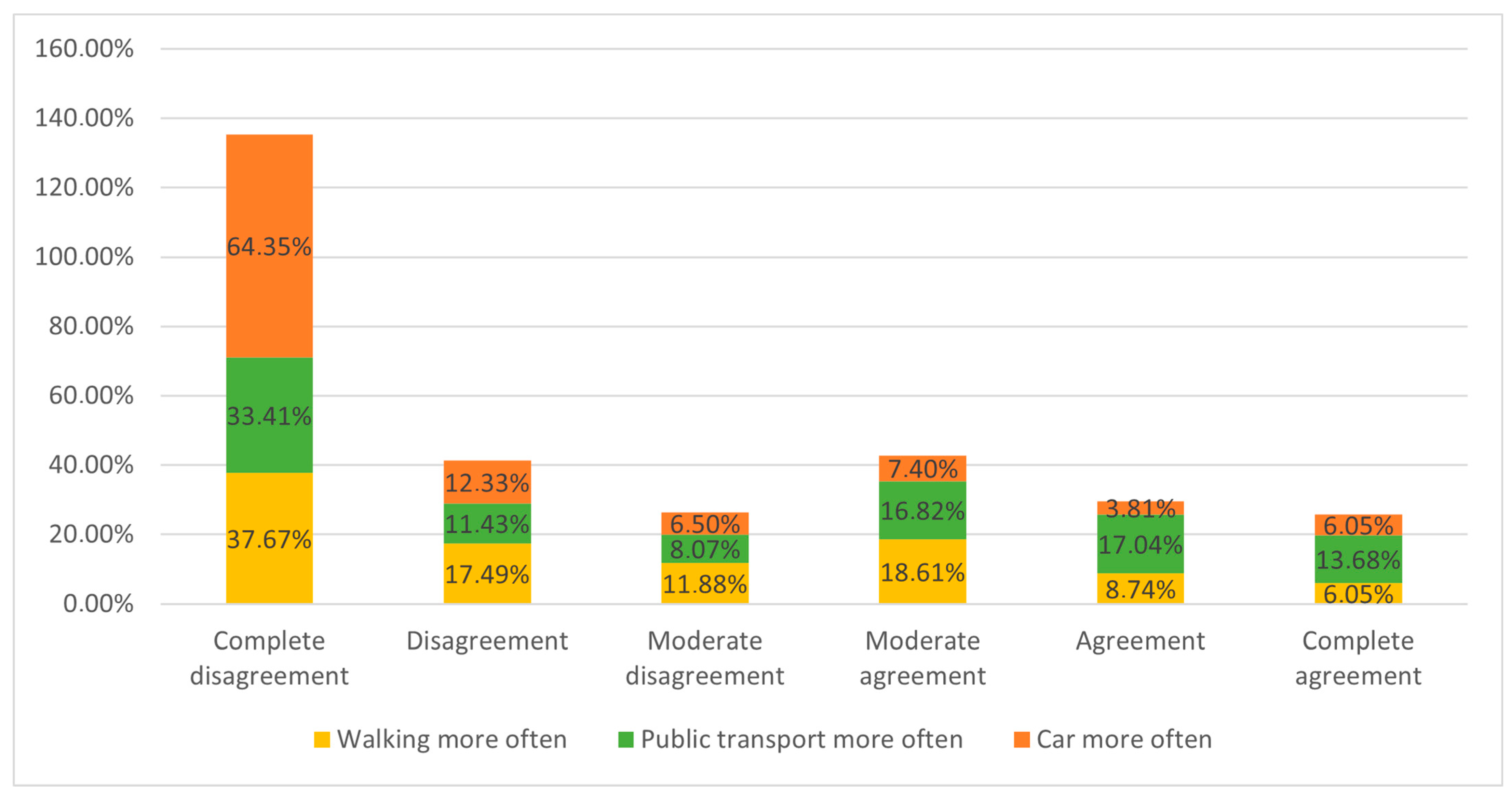

In terms of alternative modes of transportation, most respondents disagree or completely disagree with the statement that they would use the car more often, between approximately 15% and 30% of respondents. The full results are presented in

Figure 3.

6. Discussion

The debate over MHL underscores the challenge of balancing cyclist safety with the promotion of cycling. While helmets undeniably enhance safety by reducing the risk of head injuries [

13], mandatory helmet laws may deter people from cycling, thereby diminishing the broader public health benefits associated with increased physical activity and lower vehicle emissions [

16]. This paradox highlights the need for a nuanced approach to cycling safety that encourages helmet use without discouraging cycling, as evidenced by policies in Norway [

18,

31].

Purchasing and owning an urban bicycle requires a significant commitment, and many cyclists prefer to first experiment with urban cycling through shared bicycles. This serves as their initial introduction to this mode of transportation, particularly in cities with limited cycling culture. The introduction of MHL would likely discourage spontaneous use, as users may not have helmets readily available, creating an additional barrier to urban cycling. Indeed, our results show that the proposed MHL would have had a detrimental effect on both helmet usage and bike-sharing uptake. This is reflected by the reports of lesser helmet use amongst bike-sharing users and potential decreases in usage following the implementation of an MHL. Overall, these findings are consistent with observations in other cities, where helmet laws have led to a decline in bike-share usage [

22]. Fortunately, it does not seem—at least based on self-reports—that the MHL would have prompted a shift towards other, less sustainable modes of transport.

As our results make clear, there is a need to address the inherent tension between mandatory helmet usage and the spontaneous nature of bike-sharing services. For instance, to reconcile the safety benefits of helmet use with the need to promote cycling, policymakers should consider a multifaceted approach addressing education and promotion (e.g., [

18]), infrastructure improvements (e.g., [

31]), the enforcement of helmet wear among parents (e.g., [

32]), and an exploration of possible support from bike-sharing companies (e.g., [

33]).

Increased public awareness of helmet safety is essential and can be accomplished with targeted education and promotional campaigns. These campaigns should address common perceived barriers to helmet use while highlighting the benefits of helmets. This recommendation aligns with the findings that psychosocial factors, such as convenience, perception of normality, and aesthetics, affect helmet use more than mandatory policies [

18]. This approach allows for the promotion of helmet use without the need for mandates, which can deter some individuals from cycling. This view is also seen in the existing literature pointing to how campaigns promoting voluntary helmet use might help avoid the use reductions seen from the implementation of MHL in other locations and instances [

16]. Furthermore, there is a need to consider gendered norms when implementing awareness or legislative campaigns, as previous research [

19] as well as data on agreement with the proposed MHL here suggest important gender-related differences concerning the support and uptake of helmet usage.

Improving cycling infrastructure should remain a priority for policymakers. By enhancing cycling routes and ensuring they are safer and more accessible, infrastructure improvements can make cycling a more attractive option. This is backed by research by [

3,

10] indicating that well-designed infrastructure can make cycling more appealing and reduce injury risks. Improved infrastructure can help reduce the need to rely on helmets as the primary means of safety, thus supporting both safety and ridership goals.

Encouraging helmet-wearing behavior among parents offers a practical approach to reinforcing helmet use among young cyclists. According to the Theory of Planned Behavior, children are likely to adopt behaviors demonstrated by influential figures, with parent modeling playing a particularly significant role in shaping long-term safety practices [

18,

32]. Regular helmet use by parents can establish a strong example, fostering habits that persist even when helmet use is no longer mandated. For instance, one report indicates that among parents who report always wearing a helmet, 86% likewise say their child also does so [

32]. Studies further show that in countries like Norway, where helmet use is voluntary, high rates of adherence (nearly 60%) are achieved through social norms rather than legislation, underscoring the potential impact of cultural modeling [

18]. By seeing helmet use as an established practice, children are more likely to view it as a natural component of cycling, which may contribute to sustained helmet adherence into adulthood. Promoting parental modeling, therefore, aligns with a holistic approach to urban cycling safety, advancing helmet use through voluntary behavior rather than mandatory regulation [

13,

16]. However, as other research has pointed out, many socio-cultural factors influence decisions to wear helmets or engage in various forms of mobility [

18,

34], suggesting a need for context-specific research and recommendations.

Bike-sharing companies, whose users often forego helmet use, have the potential to play a role in the promotion of helmet-wearing use. Existing data shows that bike-share users are less inclined to wear helmets, and mandatory laws could discourage bike-sharing, particularly for spontaneous use [

22]. By exploring potential ways that these companies can support helmet use, such as promoting helmet safety in their operations or providing access to helmets, policymakers and companies can both work toward making helmet use standard practice among bike-sharing users. This set of recommendations offers a proactive approach that aligns with broader cycling promotion goals in Prague, suggesting similar outcomes in other urban areas.

7. Conclusions

The above study, of course, has certain limitations that should be kept in mind. The sample cannot be said to be necessarily representative of the whole bike-riding population in Prague, and as our study focused only on one city, there is an obvious possibility that these results do not translate to other countries or contexts. Furthermore, as the survey relied on self-reports, it is possible that helmet use was overstated due to some form of social desirability bias. Finally, we do acknowledge the limits of our survey and analysis, as more fine-grained data collection or analysis methods, such as longitudinal or experimental studies, may have yielded different results.

Nonetheless, what our results make clear is that the introduction of an MHL in Prague would present a dynamic and multifaceted challenge to the city’s efforts to promote sustainable urban mobility through cycling. While the law might possibly aim to enhance cyclists’ safety by reducing head injuries, the findings of this study suggest that it could also lead to a decrease in cycling participation, particularly among bike-share users. Survey data indicate that almost two-thirds of bike-sharing users would cycle less if such a law was implemented. This decline would pose a significant risk to Prague’s sustainability and active mobility goals.

To balance cyclists’ safety with the promotion of cycling, a nuanced approach is recommended. Policymakers should consider integrating educational campaigns to raise awareness of helmet benefits without imposing mandatory requirements. Additionally, investment in separated cycling infrastructure will make cycling safer, potentially mitigating the perceived need for mandatory helmet laws.

By adopting these strategies, Prague can enhance cyclist safety while promoting cycling as a sustainable and accessible mode of urban transport, contributing to its broader climate and mobility objectives. This approach supports a more holistic view of urban mobility that aligns safety with sustainability goals.