Abstract

This paper examines how mobility can be re-examined within four communities that face substantial transport barriers. Four case study communities facing mobility exclusion were investigated: (i) an ageing community in South Wales; (ii) a community of people with learning difficulties from across Wales; (iii) female university students in Pakistan; (iv) a deprived neighbourhood in mid-Wales. Using an illuminative evaluation, collating a variety of information from documents associated with the communities, it was identified that transport creates freedom, independence, and contributes to sense of purpose, worth, and can help create community. Barriers to public transport include inaccessibility of the first/last mile, services not running at required times, being delayed, and cancelled. Barriers to active travel include poor infrastructure. Not being able to be mobile affects health, not just with a lack of active travel but also missed health appointments and a lack of access to healthy foods. Already marginalised communities are further disadvantaged by the barriers reducing access to jobs, education, services, shops, and leisure. Communities want support to develop their knowledge into a package that actors can use to develop a solution, often citing the need for quantitative skills, however, other ways of utilising experiential knowledge might be more appropriate.

1. Introduction

Certain individuals face gaps in transport provision, which lead to social exclusion, reducing people’s access to work, services, shops, and appointments as well as access to leisure and recreation [1,2]. Furthermore, transport related social exclusion can also lead to a reduced quality of life due to high levels of pedestrian casualties and fatalities as well as traffic-related air and noise pollution [2,3]. Transport inequalities are highly correlated with social disadvantage, and individuals facing social exclusion are also more affected by transport exclusion and the negative health-related externalities of transport systems [2,3]. Lucas [2] notes that exclusion can be at any level, from the individual level to a macro level, but given that already excluded groups or communities are often further disadvantaged by access to transport and the negative impacts of transport, this paper examined transport-related social exclusion from the perspective of the community. Communities sometimes attempt to overcome these inequalities themselves through lobbying, facilitating, and sometimes resourcing the mobility themselves. For example, community transport or specialised transit services can provide door-to-door transport for those unable to use public transport or other modes of transport. These services are a vital lifeline for people who would otherwise be cut-off. However, this may not be enough to overcome social exclusion, only overcoming part of the issue. This article looks at how it might be possible to allow communities to have more influence over planning transport and mobility in their local area beyond just running community transport services,. Therefore addressing the role of community in encouraging more active and public transport, the use of other modes including shared bike schemes and car schemes, and identifying where technology might play a role in reducing transport need or demand. Future transport planning is at a crossroads, where one direction sees increasing technology to control transport provision vis-à-vis intelligent transport systems or autonomous vehicles, against one with less technocratic intervention, including reducing traffic rules, keeping the streets open to interpretation and people focussed, for example, shared spaces, woonerf, and home zones. What balance of these is found if the communities themselves are involved in planning?

Transport planning has shifted from directly attempting to plan for demand to more nuanced management of that demand in an effort to curtail unsustainable growth, especially around the use of private vehicles. Nevertheless, forecasting transport growth is still dominant in transport planning. However, it is widely acknowledged that transport models tend to poorly predict transport growth [4,5], and in any case that predicting the amount of travel and providing for it, or even trying to manage it, does not work to create mobility solutions that reduce transport demand. In realty, it results in an unsustainable system, prioritising independent vehicle-based mobility at the expense of healthier and more sustainable transport solutions such as walking, cycling, and using public transport.

New philosophies for transport planning include moving from predict and provide to decide and provide [6], while Vision Zero approaches integrate targets to reduce deaths from roads including those arising from collisions, pollution, and inactivity [7] from poor health, and the use of mobility capital, or deep mapping approaches [8]. These approaches suggest a greater role for understanding people within the transport system, introducing added complexity and allowing for a wider set of priorities to be examined including sustainability and health, but also creating space for an understanding of marginalisation and exclusion that has occurred in traditional transport planning. Furthermore, such approaches may involve a co-production approach, allowing the users of the service to shape and guide how the service looks, its priorities, and solutions. This approach overcomes concerns shared by actors involved in consultation processes of tokenism and becoming involved in already decided schemes or at the wrong point of the planning process. In turn, it might also help marginalised groups gain more power. Accessibility planning in the United Kingdom (UK) is still an example of having solutions done to communities rather than done with them.

Drawing on the philosophies of social justice, the movement of transport justice goes a step further, arguing that governments have the fundamental duty of providing everyone with adequate transportation and therefore mitigating the social disparities found in the current system [9]. One way to provide a better and more inclusive solution is to understand the needs of the excluded group through involvement and engagement of the group in developing the solution. Using Arnstein’s Ladder of Participation [10], current transport planning may be viewed more “doing for” rather than “doing with” a community, where community members are informed, consulted, and engaged but stops short of co-design or co-production. Co-design would be involvement of the community in designing a solution. Co-production is an ongoing process of producing and evaluating solutions. This paper aims to look at how the involvement of the community in planning their own transport solutions might help reduce transport exclusion and improve transport justice.

Miller and Wyborn (2020) suggest that co-production in planning and development leads to more inclusive and sustainable outcomes, but is rarely used in transport planning [11]. Musselwhite (2021) used a co-production approach in a case study of older people’s transport needs in Greater Manchester, where older people identified needs and issues pertinent to their mobility in their community and co-designed solutions to which the responsible transport authority, Transport for Greater Manchester, acted upon [12]. Jacobsen (2021) showed how the co-production of technology in an established Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) system allowed people to use it how they wanted, rather than simply as it had been designed, allowing for greater flexibility of use [13]. However, as noted by Nostikasari and Casey (2020), in a U.S. case study of Dallas-Fort Worth, Texas, privilege and power are still given to transport prediction models over more grounded and specific experiential knowledge from the residents (and even planners themselves) [14]. Similarly, Stepanova and Polk (2023) noted in the co-development of Haga Station, Gothenburg, Sweden, how institutional co-production among professionals is privileged over citizen co-production, since some of the major decisions have already been made prior to involvement [15].

This paper looks at what happens if transport is viewed from a community perspective; how far community understandings of their mobility might help in shaping solutions to their mobility. Four case studies were examined, which were selected for seedcorn funding in a competitive tender for research that linked with policy and practice to answer a transport and health community issue. Each of the four case studies were examined through a process evaluation.

2. Materials and Methods

Design: A formative process evaluation was carried out using an illuminative approach. This approach captures a myriad of materials as is found in the field including documents, interviews, and blogs and utilises a qualitative approach to analyse and assimilate the data. An illuminative methodology is a flexible methodology that draws on available resources and opportunities, utilising different techniques in order to discover and document what is happening from different perspectives in the community to illuminate the most significant features, recurring concomitants, and critical processes [16,17].

Case Studies: The four case studies examined were the winners of the Transport and Health Integrated Research Network (THINK) project call for seedcorn funding Transport in the Community. The projects are all nearing their completion at the time of writing (June 2023), having begun in September 2022. The case studies are self-defined communities of transport need, who are willing to work together to solve a transport solution, but represent very different transport needs, different transport options, different geography, locations, and communities and therefore represent four very different communities. These case studies were deliberately chosen to help identify elements that are common despite different contexts and backgrounds. The case studies were:

Case study 1: Age Morgannwg Case Study. Older People and Mobility (led by a charity for older people living in Rhondda Cynon Taf, Bridgend, and Merthyr Tydfil, a series of networked small/medium towns in the historic ex-mining towns of South Wales, UK). This case study centred on the needs of older people for transport assistance to access support groups and activities being run in their local urban area. The community wanted to collect information to help them source a new transport service to meet the needs of older people. The project first facilitated a survey on transport need and transport barriers and was completed by 75 older people in the community, followed by group discussions with older people and support staff. The data were analysed by the community and fed in to provide a better transport service more tailored to older people’s needs. The findings of this survey and group discussion are not contained in this report, moreover, the outputs and outcomes from the act of doing this, and any ongoing processes while carrying this out.

Case study 2: Learning Difficulties Case Study. Community Transport Association, Wales: Social inclusion of people with learning difficulties through community-led transport across Wales, UK. The identified community in this case study was young people with learning difficulties who faced significant transport barriers, leading to the exclusion and marginalisation of an already socially excluded group. The project was used as a catalyst to encourage discussion and action around changing working practices and identify ways in which bus, rail, and community transport services could be adapted to support the mobility needs of people with learning difficulties. The communities here came from a variety of different locations, from rural to urban including suburban.

Case study 3: Young Women in Pakistan Case Study. Fatima Jinnah Women University, Pakistan: Increasing Mobility of Young Women in Pakistan through the use of Scooties. Scooties are scooters (small motorbikes or mopeds) in Pakistan. This project focussed on the mobility of female students aged 18–25 who faced transport exclusion through social or psychological abuse and sexual harassment on public transport. The project offered to purchase scooties, along with training and support, for female students to help them continue their education. The community here focussed on female students in a variety of urban and suburban areas.

Case study 4: Newtown Case Study. Sustrans: Encouraging Active Travel In Newtown. This project aimed to help a community in the Treowen estate within Newtown, Powys, Wales, with their active travel to enable them to walk, cycle, and wheel more. The project was carried out using co-production with the community identifying barriers and developing solutions around sharing and mapping information and developing companion and buddy schemes.

Procedure: At the time of analysis, each case study had been running for nine months. Each case study provided a variety of information as noted in “Tools” (below), which was collated, analysed, and themes developed.

Tools: Illuminative evaluation examines material that is already being produced within each case study. In each case study, the following data that were available was examined:

Application form. The form used to apply for the funding, which included sections on a problem needing to be solved, methods to solve it, and where they hoped the project would lead in the future.

Correspondence. In the form of (1) emails between the case study leaders and the wider THINK project team as the project developed and (2) subsequent online discussions between the case study leads and the THINK project team.

Discussions between the case study leads, each other, and the THINK project team were conducted at the inception start-up meeting and throughout the project.

Documents of the first reports and blogs submitted to the project team. The case study teams had to provide a report three months into their award and were encouraged to provide a blog for the THINK website.

Data Analysis: Data from the various sources that were assembled from each case study area were assimilated into a single transcription so that it was in a usable format for thematic analysis. Analysis was carried out through the researcher reading and re-reading the assembled text for each case study and identifying and highlighting the key and sub-themes; no analysis software was used due to the variety of sources assembled together. The themes and sub-themes were highlighted and noted using coloured pens on printed transcripts. The project employed a priori analysis, looking for certain themes already established in the previous literature and knowledge, and post hoc analysis for themes that were developed and read from within the data. In terms of a priori analysis, three themes were looked at for potential changes in (i) health; (ii) travel behaviour and; (iii) community cohesion. Each time text that fitted these themes was found, it was highlighted, and additional points were noted that formed sub-themes. Allowing space for post hoc themes to be developed through reading and interpreting the data further identified two additional themes of (i) transport democracy and; (ii) inequalities. The illuminative approach uses the concept of ‘recognition of authority’ and cross-checking triangulation to ensure that the data collected are robust [16,17]. The data analysis considered the difference in power to which different data are acquired, for example, someone speaking from their own authority and experience is classed as a different power to someone speaking on someone else’s behalf. This is acknowledged in creating themes and sub-themes. Data were also triangulated across case studies for the similarity of themes, despite differences in the case study context and design, and as such, the findings can be somewhat generalised to other locations, since the contexts and design of the case study areas were so diverse.

3. Results and Discussion

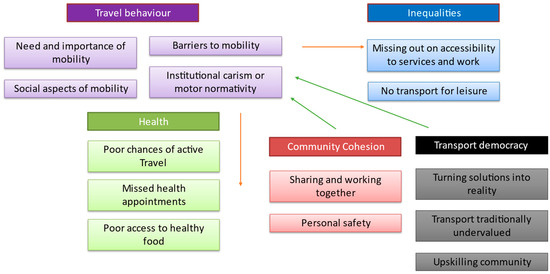

The findings are described around the five key themes, reported in terms of travel behaviour, equalities, health, community cohesion, and transport democracy, with further sub-themes under each (see Figure 1). Three of the themes (health, travel behaviour, and community cohesion) were derived from previous literature and two themes (transport democracy and inequalities) were added through reading and analysing the data. Sub-themes were all generated through analysis of the data. The most significantly discussed theme, travel behaviour, is important for people to get from A to B (an a priori theme that was expected to be found) and also included important sub-themes of social aspects of mobility and the need and importance of mobility (both derived from the analysis of the data itself). Two further sub-themes of travel behaviour were negative barriers to travelling and the underlying notion of car dominance or institutional carism [18] or motornormativity [19]. These two sub-themes in turn feed into further inequalities (a theme derived from the analysis of the data itself) further divided into sub-themes of people missing out on accessibility to services and work and also of leisure, and a main theme of facing poorer health outcomes (a priori category) through sub-themes of a lack of active travel, missing health appointments, and poor access to healthy food. Working together on transport solutions improves community cohesion (a priori main category) through the two sub-themes of sharing and working together and understanding personal safety issues and transport democracy, which can help overcome some of the barriers through the sub-themes of turning solutions into reality, re-evaluating the importance of travel, and upskilling community members. Each of these themes will now be looked at in more detail.

Figure 1.

The five key themes from across the case studies, their sub-themes, and how they interlink (red arrows show a negative relationship and green arrows show positive relationship).

Key theme 1: Travel behaviour. The need and importance of being mobile, followed by barriers to this, were most often discussed in community settings. The dominance of much of the information provided was around the barriers. The social aspects of the journey itself are provided as a special sub-set of the need and importance to be mobile, as both a facilitator to mobility but also as a positive outcome of mobility itself. Underlying both of these were issues around the dominance of the car in community thinking and provision, demonstrating institutional carism [18] or motornormativity [19], where the car is both unconsciously and consciously prioritised over other forms of transport. Groups mentioned the need for technology here to help collect data on travel behaviour through surveys, diaries, and to help handle or analyse the data.

Sub-theme 1.1. The need and importance to be mobile. The need to get out and about was emphasised in all case studies. Not just to access health care, education, shops, and services, but simply to socialise and to feel part of the community. In the Bro Morgannwg case study, older people noted how nice it was just to get out and see the world around them and how that improved their well-being. In this case study, a survey was run with the community which found 55% stressed that the importance of mobility was simply ‘to get me out of the house’, with 47% answering ‘to lift my spirits’, and a further 47% answering ‘to socialise’, and finally, 43% answering ‘to feel part of a community’. This was commensurate with research on older people’s mobility needs, which suggests that there is an undervaluing of the importance of mobility for affective (for independence, freedom, for a sense of purpose, etc.) and aesthetic purposes (getting out and about to see the world around, to enjoy mobility itself), which are vital for people’s health and well-being and are often ignored or overshadowed by practical needs [20].

Sub-theme 1.2. Social aspects of the journey itself. It is important to note though, that the social aspects of the journey may not be required just for the journey itself. People do not see their journey in isolation to what it is they are going to do. As an example, in case study 1 with Age Connects Morgannwg, older people would like and need a trained volunteer or support worker to join them on their whole journey and destination including the activity at the end, evidencing that transport often is not the only thing that people need support with and how it fits wider priorities. Transport planning separates the means and the end, while community planning suggests that the two might be better combined.

In addition, as noted in the Learning Difficulties and Community Transport case study with people with learning disabilities, the psychological aspects of the journey are vitally important and can be brought about by the community transport driver:

“Accessible transport is much more than wheelchair accessible services and door-to-door provision. It involves people feeling valued, being treated with respect, and provided with transport options that provide real choice and independence” (Learning Difficulties case study).

Previous research noted the importance of the social aspect of the bus, and the importance of the driver in particular to making or breaking a journey, both on public transport, on bus and rail, and on community transport [12].

Sub-theme 1.3. Barriers to mobility. In each community, there were identified issues with mobility, where particular groups of the community could not access what they needed or wanted. People want to get out more than they do but face barriers in doing so. People would like to use public transport more than they currently do. In the Age Connects Morgannwg case study, a survey run within the case study found that despite 79% of older people living on a bus route, only 48% used it. Issues for not using the bus included the lack of accessibility, bus stops being too far from home, and the service not running at the right times to meet the appointments they were going to. Furthermore, there were issues noted around struggling to stand outside in the cold waiting for a bus, not being able to walk up a hill with shopping from the stop, refusing to take assistance dogs or wheelchairs, and people not being able to rely on public transport to get to appointments as they were so frequently delayed or did not turn up at all. These issues have been discussed by older people in previous research (e.g., [12,20]). If the community members were unable to use the public bus, older people would turn to friends and family for lifts, but would feel a huge burden. This is commensurate with previous research that suggests that getting lifts from family, friends, and even neighbours occurred but a lot of guilt was found, with people feeling a sense of being a burden on others [21]. Bringing services together was also discussed as well as how to provide better integration. Mostly, this was discussed in terms of better timetabling or coordination between companies, possibly overseen by an executive, but technology such as Mobility as a Service was also briefly mentioned as a way to integrate mobility better.

Transport barriers are not just accessibility or service based. Significant psychological issues of understanding norms, of building confidence, and having general social support were all noted in the case studies. Previous research noted the importance of understanding the social norms surrounding transport use and people who had not used transport for a number of years being unable to overcome the fear of understanding how to use the system [20]. Musselwhite and Scott (2019) noted how social support can overcome this barrier, and schemes such as bus buddies, where people get someone to ride with who can support and help, can mean that people can travel where they want [8].

Sub-theme 1.4. The dominance of the car. The dominance of the car in terms of perceived accessibility and the freedom they bring was a key theme throughout the case studies. In addition, it was often noted that people did not have the knowledge of alternatives. In the Newtown case study, it was clearly noted that many members of the community aspired to own a car even though affording one was difficult and not owning a car really reduced their confidence in society:

“Feeling like a lesser member of society, perhaps particularly in a more rural area.” (Newtown case study).

Overall, there was a need to change the narrative, where community members were “Feeling impaired by not having a car, rather than liberated.” (Newtown case study).

This demonstrates that institutional carism [18] or motornormativity [19] also affects emotions.

Key theme 2: Inequalities. Analysis of the case studies revealed just how transport contributed to inequalities already found in the community groups, revealing links to social exclusion. The analysis suggests that people miss out on opportunities in accessing services, education, and work as well as leisure.

Sub-theme 2.1. Missing out on opportunities accessing services and work. All the projects examined communities that were excluded from accessing vital services. These services include activities that help them directly with their health and well-being and as noted above, can impact their attendance at health care appointments. With younger groups, with the young women in Pakistan or those with learning difficulties across Wales, direct links with education and work opportunities were missing, and missing links to the community were especially noted by the case study involving older people. It was felt that a better understanding of the community need for transport services coming from the community themselves would help enhance better provision and better use of such services.

Sub-theme 2.2. Transport for Leisure. All groups noted the importance of mobility to fulfilling leisure activity, but this was especially noted for older people in the Age Connects Morgannwg case study and those with learning difficulties case study. Previous research suggests that around a third of people with a learning disability spend less than an hour outside of their home on the weekend [22]. Having an active social life and being involved in leisure activity is linked to the health and well-being of older adults and those with learning difficulties, but the importance of transport as an enabler to get to and from such activity is often undervalued or underplayed [23]. It was noted just how much both public and community transport tended to run 9–5 weekdays, with a reduced or no service available out of these times. This particularly reduces people’s accessibility to leisure activity that takes place outside of such hours.

“The sector has delivered services mainly on a Monday to Friday, 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. basis, with provision outside of those hours by agreement and primarily for transport to health appointments. Growing awareness of a gap in community transport services for younger adults with learning disabilities who want to travel in the daytime, evenings or at weekends, and a wider need to ensure transport services across the board take an inclusive approach that meets the needs of all passengers” (Learning Difficulties case study).

Key theme 3: Health. The health outcomes of transport use were noted and discussed among the community case studies. Barriers to active travel were noted across all groups, with older people and those with learning disabilities blaming themselves for not being able to be active. Missed health appointments were a direct implication of poor transport provision and were discussed among the case studies. Finally, a lack of mobility accessing healthy food was also another issue noted.

Sub-theme 3.1 Active travel. Most notable among the case studies was how people felt excluded from performing transport behaviours that also improved their own health. Across all case study sites, people noted difficulties in walking and cycling. Narratives in the case studies suggested that there was a tendency for older people and those with learning difficulties to attribute some of that to their own lack of skills and ability, but discussions in the case studies changed the narrative to shift the blame onto the provision of infrastructure and the surrounding environment. In line with a transport justice approach, provision should be made so such groups do not feel excluded from being actively mobile. Case study Leads noted that much could be done locally to encourage such marginalised groups to carry out more active travel within the local community if their needs were understood and appropriate provision made for them. This led to co-produced solutions being discussed, for example, improving the infrastructure by making sure pavements were in good order and placed where people wanted them, putting in extra pedestrian crossings, and communities often cited the need for a better understanding of desire lines in creating these solutions. Similar to the Greater Manchester case study [12], active travel could be better supported by understanding the needs of local marginalised groups and being centred around the better provision of dedicated spaces to walk, better crossing points, and better lighting. In addition, sharing information was important, and communities creating their own maps of active travel in their local areas was discussed as a potential solution.

Sub-theme 3.2. Missed heath appointments. The marginalised communities all cited difficulty in getting to medical appointments due to transport accessibility, times, and cost, and this resulted in some groups missing medical appointments altogether, impacting on their health and well-being. This resonates with recent studies that suggest that around 35% of people have missed or delayed a health care appointment, and a further 18% missed medical treatment due to transport issues including cost and accessibility [24]. This was worse for already marginalised groups and those in rural areas [25]. Solutions discussed included examining how hospitals could integrate the appointment times better with both public and community transport. A solution again was mooted in the case study in Greater Manchester [12] and has been trialled with some success in Devon as part of their Total Transport Approach, Stockport Primary Care Trust, Greater Manchester, and Golden Jubilee Hospital, Clydebank, Scotland, with the cost of making it work outweighing the cost of the missed appointments over time.

Sub-theme 3.3. Accessing healthy food. The Newtown case study especially noted the need to create better active travel access to supermarkets rather than the fast food outlets that were situated in residential areas. Identifying and opening up pathways to such locations is vital, and learning from community members who have found ways to access and use supermarkets actively is important for health and well-being.

Key theme 4: Community cohesion. The very process of bringing communities together to work together on transport issues and solutions creates community cohesion and shows key links to community engagement, which this process fosters. The case studies identified sharing and working together including education and training, and how working together in a community could improve personal safety issues and concerns.

Sub-theme 4.1. Sharing and working together. The process of understanding and sharing needs among a community often leads to better community cohesion itself. The tightly defined communities in this project meant that conflicts between members were low. It is acknowledged that this might change if the process is expanded to involve other communities, as noted in the development of Haga Station, Gothenburg, Sweden [14].

Sub-theme 4.2. Education and training are programs continually asked for by the communities. For example, in the Young Women in Pakistan case study, road safety training and training in using the scooties (scooters) were added as being necessary for the community.

There was learning that happened within the communities of the case studies, for example, a main issue identified within the Newtown case study was about knowledge of the existence of a dedicated space for walking:

“There are paths through [the housing estate], but entrance points are unclear. This may deter people from trying to find them.” (Newtown case study).

On working together, the tacit knowledge of the existence of these can be shared, especially on the re-drawn map, the outcome of the Newtown case study.

Sub-theme 4.3. Improving personal safety. Personal safety was the central reason for the case study from Pakistan, but the issue of safety was evident in all case studies. Mobility is restricted for young women in many areas of Pakistan due to cultural norms, meaning that many women do not finish their education. In particular, walking and public transport make them vulnerable to potential attack. A short-term solution identified was to provide the young women with scooties (scooters), which would enable them to be mobile and feel personally safe. Longer-term solutions are being discussed, but cultural shifts take longer. Also being discussed are the best methods for these to be made available to the young women. Different models including loaning them and shared schemes as well as reducing the overall costs were discussed, with shared version of the scheme being most attractive due to costs and a lack of worry over maintenance or theft. Also discussed was making the short-term solution more sustainable through the use of electronic scooters or equivalent, though barriers to these are the increased expense, further emphasising the need for owners to have a grant or to be able to borrow them as part of a shared scheme. Safety was also an issue for people in the learning difficulties case study, where the use of public transport was seen as a flash point for disability discrimination. Sharing knowledge in the case studies among community members helped a little with understanding issues of personal safety and could help allay fears. There were also offers of support among members so that people could try out public transport or try a new walking or cycling route with a buddy.

Key theme 5: Transport democracy. The final theme examined how looking at transport within a community lens changes the perceptions and the nature of transport decision-making, and how it increases democracy in transport and mobility issues and has an impact on community and transport planning. First of all, the community groups established themselves to make a difference, and nine months in (at the time of writing), the communities are ready to consider turning the emerging solutions into reality and beginning to discuss how this might happen. When looking at this, two additional sub-themes emerge. First, there is the concept that in all activity within their groups, transport provision and accessibility have been underplayed or undervalued. Then, there has been a tension in the groups over wanting to be heard by decision-makers and feeling that they lack the skills in order to represent their community. The domination in transport of modelling and quantitative data over experiential knowledge has resulted in community members often wanting skills to help them provide data that might get used by decision-makers.

Sub-theme 5.1. Turning solutions into reality. The communities discussed how to action the issues that arose from their communities. What was common was that working in a community is a first step that then needs to be joined together with other community members to share local knowledge and lobby together through local community transport groups. Another source of sharing local knowledge and turning knowledge into action was to work with elected officials and other decision-makers including local transport providers who ran services in the community. In the previous Greater Manchester example [12], shared findings between community groups to co-develop solutions and the co-developed solutions were then shared with the wider transport planning authority, Transport for Greater Manchester. The need for the transport planning authority to be involved in the whole process from the beginning and to find mechanisms for change within their own strategies were identified at the start of the project. It is suggested that it would not be as successful to simply “go to a transport planning authority or transport executive” and ask them to deliver what was found without initial “buy-in” from the authority.

Sub-theme 5.2. Underplayed or undervalued transport. Transport tends to be undervalued; this was acknowledged especially in the Age Connects Morgannwg case study where previous funds provided for activities for older people had to be diverted as people could not get to the activities provided, which led to the application for these funds,

“Originally the project did not have transport but an activities coordinator wage. By end of January after speaking with potential clients, volunteers care givers and receivers it became apparent that transport was more of an issue, so we diverted the funding from the activities coordinator and instead funded a free minibus to take people to the coffee morning.” (Age Morgannwg case study).

Sub-theme 5.3. Upskilling the community or not? The need for high quality data was noted by communities. In contrast, there was a concern about the lack of skills within the community in collecting such evidence. Some of this may be unfounded, and challenging the notion of quantitative evidence being a necessity in delivering transport solutions needs further examination. For example, the use of deep mapping found different priorities for redevelopment among the community members to those found through the survey and consultation work [8]. In addition, the Greater Manchester case study [12] did not use any quantitative data in developing and prioritising the key recommendations that were taken up by Transport for Greater Manchester. Nevertheless, as previously identified, transport modelling and associated data are privileged over narratives, case studies, and experiential knowledge [16,17]. In any case, the quantitative skills needed could be part of the co-production process of creating community co-researchers. The upskilling of community members to co-research their community can be successful in better understanding the community needs and issues [26]. Communities mentioned the need for technology to help support data collection and analysis. Tensions remain, however, in how far community researchers can be upskilled into academic researchers or how far they provide a different skill and therefore offer a different perspective [27]. There is a feeling here in the findings that community members want skills to show what they are finding in the community, and they themselves feel that they want the academic skills to provide this in a robust way recognisable to funders and decision-makers in order to enact change. However, it could be argued that it is precisely the lack of these skills that provide the insight into community issues that is so missing in transport planning at the moment, where certain community needs are excluded. To this end, it might be better to change the philosophy and the system to recognise the importance of what community knowledge brings to the conversations, acknowledging that this requires a change in mindset from the technocratic, positivist underpinnings of forecast modelling, cost–benefit analysis, and other such quantitative models.

The experiential knowledge of the case study groups often led to differences produced by the communities compared to what had been produced by the professional authorities. This was not just privilege between modes, for example, championing motorised vehicle activity over-active travel, but also within active travel discussions. For example, active travel maps that had been produced by professional authorities in the Newtown case study showed very different locations to where the active travel was actually carried out as identified by the community. The maps produced professionally had labels of quality, for example, the width of the pavement, which were simply not important to the community themselves. This led to a very different map produced by the professionals, making an area look poorly connected in terms of active travel, which was not necessarily the case. The need for walking and cycling maps to be better suited to communities based on what is really important to that community is vital.

4. Conclusions

The findings from the four community case studies highlight some key issues across all groups, suggesting that generalisability across communities might be found given that they were all very different case studies. Importantly, they all found that transport and mobility are absolutely vital for people: it connects them to what they want to do, and it is vital for independence and freedom, especially among groups who might otherwise find it difficult to get out and about. Social support to enable this to happen is vital, and people talked about having support continuously from the journey to the destination as well as even at the destination. Barriers in the groups were numerous and easy to talk about. Some communities internalised the barriers, especially around active travel, feeling that they could not engage with what was required to walk or cycle. Communities tried to dispel this myth, and in the spirit of transport justice, tried to move the attribution to the infrastructure or level of service provided to enable them to be able to walk or cycle. The dominance of the car and private mobility on people’s thinking meant that it was perceived that certain types of mobility and certain journeys would only be able to be performed in a car. The result of this means that in some communities, people aspired to own a vehicle. Motorised vehicles were seen as a quick fix to overcoming these barriers. Even in the case study providing young women with scooties, it was seen as a short-term quick fix to the institutional and cultural change that is needed to reduce the harassment felt by women using public transport. Discussions on making private motorised transport more sustainable then took place. What the groups wanted was to do something about the barriers and be able to be more mobile. They were highly motivated to create interventions that would reduce the barriers, and the communities immediately discussed their own solutions, resourced socially, where people shared best practice or their own innovation to make mobility work in discussions, and in some case studies also attempted to map it.

Sometimes, the change needed requires additional resources and may require different actors to make that change, and the next stages invariably involve decision-makers who can enact some of the solutions that require larger interventions and turn them into action. As noted in previous community co-production techniques, this may involve conflict, which needs to be carefully managed [15]. Anxiety about presenting the findings in a way that will be acted upon means that the communities wanted to package up the experiential knowledge gained in the groups in a more systematic way to inform actors to make a change, often asking for quantitative or even modelling skills to do this. However, it could be argued that the traditional privileging of quantitative data over experiential knowledge can be challenged [14,15]. In terms of technology, very little has been discussed in terms of the provision of transport services, other than technology to bring services together, as might be found, for example, in supporting Mobility as a Service. Technology was most frequently mentioned in terms of use in data collection, for example, in collecting data to underpin the community ideas and planning, whether that is software for running questionnaires or surveys, or something to help analyse or handle the data. Overall, it can be said that technology did not focus highly in community planning around transport. Finally, the case studies articulated that local knowledge about not using public transport needed to be better understood. Underuse of a service might only need a small change to make it really used, for example, it runs at the wrong time or on a slightly wrong route, something that the local communities felt that they could provide but were not given the opportunity to do so. This was noticed in previous research, especially in rural difficult to reach areas, where the provision of services is based only on use, rather than on understanding community need [28].

The conclusion from judging these four case studies suggests that allowing for more detailed involvement and engagement of communities in their own transport planning certainly revealed new insights into barriers to transport use and their link with other forms of exclusion and poorer health. In addition, insights into how these might be overcome are useful through developing a co-design or a co-production approach. As such, the findings suggest that the local administration responsible for transport planning should involve communities in co-designing or co-producing the plan. In addition, the involvement and engagement of the local community in planning their own transport solutions were good for the people themselves, creating a cohesive community, learning from one another, and developing a concept of transport democracy, especially if discussions could be seen through to action. However, there are three caveats that must be taken into account: (1) the concept of institutional carism and motornomativity means that it is very difficult for communities to think outside of the provision for cars and other motor vehicles in their thinking around solutions; (2) the concept of the perceived need for statistics and data meant that people often wanted to support their argument with data that they did not have; (3) it will take time to build up community understanding and identify routes into community practice. These elements would need to be built into any strategy aimed at moving transport planning from the participation ladder from doing for to doing with the community.

It must be remembered that the findings here represent only four case studies and rely on qualitative analysis. Limitations to this include a difficulty with generalisation and issues with subjectivity and replicability. This was managed through two approaches in the research: first by picking a diverse set of case studies in terms of the needs and issues, geography, and context, and identifying where commonality still existed between themes and where differences were found and second, using recognition of authority and cross-checking triangulation to ensure that the data collected were robust. However, of course, different findings could be identified if different methodology, data, and case studies are used. It is suggested that further studies are needed to help develop the findings and strengthen the recommendations from this study.

Funding

This research was funded by Health and Care Research Wales.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by Aberystwyth University’s Psychology Ethics Committee (ethics number 21791; granted on 3 May 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Lee, E.A.L.; Same, A.; McNamara, B.; Rosenwax, L. An Accessible and Affordable Transport Intervention for Older People Living in the Community. Home Health Care Manag. Pract. 2018, 30, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, K. A new evolution for transport-related social exclusion research? J. Transp. Geogr. 2019, 81, 102529. [Google Scholar]

- Mackett, R. Social Exclusion and Health, Related to Transport. In International Encyclopedia of Transportation; Vickerman, R., Noland, R., Ettema, D., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin, P. Trends in Car Use, Travel Demand and Policy Thinking; International Transport Forum Discussion Paper, No. 2020/27; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), International Transport Forum: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, P. Forecasting Road Traffic and Its Significance for Transport Policy. In Transport Matters; Docherty, I., Shaw, J., Eds.; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, G.; Davidson, C. Guidance for transport planning and policymaking in the face of an uncertain future. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2016, 88, 104–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitelegg, J. Mobility: A New Urban Design and Transport Planning Philosophy for a Sustainable Future; Straw Barnes Press: Church Stretton, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Musselwhite, C.; Scott, T. Developing A Model of Mobility Capital for An Ageing Population. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martens, K. Transport Justice: Designing Fair Transportation Systems, 1st ed.; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnstein, S.R. A Ladder of Citizen Participation. J. Am. Inst. Plan. 1969, 35, 216–224. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, C.A.; Wyborn, C. Co-production in global sustainability: Histories and theories. Environ. Sci. Policy 2020, 113, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musselwhite, C. Prioritising transport barriers and enablers to mobility in later life: A case study from Greater Manchester in the United Kingdom. J. Transp. Health 2021, 22, 101085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, M. Co-producing urban transport systems: Adapting a global model in Dar es Salaam. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2021, 17, 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nostikasari, D.; Casey, C. Institutional Barriers in the Coproduction of Knowledge for Transportation Planning. Plan. Theory Pract. 2020, 21, 671–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepanova, O.; Polk, M. The role of co-production in a conflictual planning process: The case of Haga station in Gothenburg, Sweden. Urban Transform. 2023, 5, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parlett, M.; Hamilton, D. Evaluation as Illumination: A New Approach to the Study of Innovation Programmes; SCRS: Edinburg, UK, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Parlett, M.; Hamilton, D. Evaluation as Illumination. In Curriculum Evaluation Today: Trends and Implications; Tawney, D., Ed.; SCRS: London, UK, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Musselwhite, C.B.A. Designing Public Space for an Ageing Population, 1st ed.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, I.; Tapp, A.; Davis, A. Motornomativity: How Social Norms Hide a Major Public Health Hazard. PsyArXiv 2022. Available online: https://osf.io/preprints/psyarxiv/egnmj/ (accessed on 2 August 2023).

- Musselwhite, C.; Haddad, H. Mobility, accessibility and quality of later life. Qual. Ageing Older Adults 2010, 11, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, A.; Musselwhite, C. Older peoples’ experiences of informal support after giving up driving. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2019, 30, 100367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mencap. Research on the Lives of 18–35 Year Old People with Learning Difficulties. 2019. Available online: https://www.mencap.org.uk/press-release/almost-1-3-young-people-learning-disability-spend-less-hour-day-outside-homes-survey (accessed on 2 August 2023).

- Graham, H.; de Bell, S.; Flemming, K.; Sowden, A.; White, P.; Wright, K. Older people’s experiences of everyday travel in the urban environment: A thematic synthesis of qualitative studies in the United Kingdom. Ageing Soc. 2020, 40, 842–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochran, A.L.; McDonald, N.C.; Prunkl, L.; Vinella-Brusher, E.; Wang, J.; Oluyede, L.; Wolfe, M. Transportation barriers to care among frequent health care users during the COVID pandemic. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasniuk, S.; Crizzle, A.M. Impact of health and transportation on accessing healthcare in older adults living in rural regions. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2023, 21, 100882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas-Hughes, H. Interlude: Community Researchers and Community Researcher Training. In Imagining Regulation Differently, 1st ed.; McDermont, M., Cole, T., Newman, J., Piccini, A., Eds.; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barke, J.; Thomas-Hughes, H. Community Researchers and Community Researcher Training: Reflections from the UK’s Productive Margins: Regulating for Engagement Programme; University of Bristol Law Research Paper Series 010; Bristol University: Bristol, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Miwa, T.; Wang, J.; Morikawa, T. Are seniors in mountainous areas able to realize their desired trips? A novel approach to estimate trip demand. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2023, 175, 103776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).