Abstract

The way in which people choose to travel has changed throughout history and adaptations have taken place in order to provide the most convenient, efficient and cost-effective method(s) of transport possible. This research explores two trends—technological and socio-economic change—by discussing the effects of their application in the renewed drive to promote car clubs in Greater London through the introduction of new technologies and innovative ways in which a car can be used and hired, thus helping to generate new insights for car sharing. A mixed methods approach was used, combining secondary data analysis obtained from a car club member survey of 5898 people with in-depth, semi-structured interviews. Our findings show that there is an opportunity to utilise car clubs as a tool for facilitating a step change away from private vehicle ownership in the city. In addition, the results suggest that car club operators are seeking to deliver a mode of transport that is able to compete with private car ownership. In terms of policy implications, such findings would suggest that compromise is necessary, and an operator/authority partnership would offer the most effective way of delivering car clubs in a manner that benefits all Londoners.

1. Introduction

Car clubs are a method of transport provision that have served Londoners for several years, with data on this particular mode and its use in the city first recorded in 2007 [1]. As a result, car clubs are commonly recognised as one of the more mature forms of disruptive transport serving the city [2,3]. While car clubs have long been established, it is their evolution in recent years, both in the context of London and more globally that has generated interest. Their growth in popularity, both in terms of membership and ridership, has been enabled by technological advances and the rise of the sharing economy, which have made accessing and travelling by car clubs easier and more practical over time [4,5].

The impact of these enabling factors has not only been recognised in academia, but also by governmental organisations such as the Department for Transport, as the following excerpt from its Future of Mobility Urban Strategy shows:

“New models based on shared use or ownership of vehicles are proliferating, enabled by digital platforms and in line with a shift towards a sharing economy in other sectors.”[6] (p. 22)

As a result of this changing environment, there are increasing calls for further exploration into the benefits of car clubs, particularly in the context of London where the service they provide continues to be piecemeal in nature. First, the findings discussed within this paper provide additional evidence to aid understanding of the role played by car clubs and will consequently facilitate further investigation into how car clubs can be better utilised in the city in order to complement existing sustainable transport modes. In addition, this paper also contributes new material to this field of transport research as a result of its specific focus on the role of technology and access-based consumption. While both ‘enablers’ have been recognised in the literature for their ability to make car clubs a more appealing option [7,8], the application of these economic principles to a mixed methods piece of research in the context of London provides new insight into this evolving transport mode, which is attracting substantial interest due to its adaptability and potential to replace private car ownership.

The article is organised as follows: Section 2 discusses the literature on car clubs, disruptive technologies and the sharing economy. Section 3 presents the case study which provides context for the use of car clubs and the role they play within Greater London. Section 4 describes the methods used in the analysis. Section 5 discusses the findings of the analysis. Section 6 offers a discussion of the findings, considering whether the mechanism of access over ownership could work effectively for car clubs in London. The final section draws conclusions from the findings and provides recommendations to promote change and encourage the growth and resultant uptake of car clubs in Greater London.

2. Literature Review

Both within London and beyond, the continued growth of car clubs represents an interesting phenomenon as it comes at a time when private car ownership is arguably peaking or even declining. Coined by Metz (2013), the term ‘peak car’ refers to a theory which suggests that the number and distance of trips undertaken by private car has plateaued when measured against other modes of transport [9]. This can be observed in the London context, as evidenced by Transport for London (TfL) travel data, which shows that car trips had declined from comprising around 50% of all trips in 1993 to only 38% by 2013 [9]. This decline is perhaps not surprising considering the densification of London’s urban form [10], exacerbated by substantial population growth, and increasing capacity constraints of London’s road network.

Further evidence of the shifting travel choices of Londoners is provided by the number of car free households in central London: in 2010, 55.7% of households were car free, while in outer London, 30% did not have a vehicle. With regard to the overall context of the city, these figures represent a 4.1% increase from the 2011 Census [11]. This evidence is particularly important for promoters of car clubs, who argue that they provide a step change away from private car ownership. For example, Birdsall (2014) explains that car clubs are a transport mode that have the ability to fill a gap and help resolve the first and last mile challenge for multimodal trips [12]. They can also be used for trips where it is preferable to have access to a vehicle in order to carry goods. In this respect, promoters of car clubs argue that the mode is complementary to public transport and active travel by acting as a stop-gap solution in the transition away from private vehicle ownership. However, the evidence supporting these claims has met with some opposition, particularly regarding newer forms of car clubs such as point-to-point and free-floating models. These models have been interrogated by some scholars due to a lack of research and evidence [12,13] to support the case for encouraging the uptake of public transport and active travel modes [3,14,15], while others have challenged the premise entirely by presenting evidence to suggest that these models, in some cases, may actually reduce the number of trips undertaken by sustainable modes of transport.

This evolving London context is perhaps the first stepping-stone in understanding how this symbiotic relationship between access-based transport and technology may continue to flourish in the future. For example, the London Assemblies 2018 publication, ‘Future transport: How is London responding to technological innovation?’, identified car-club services as offering a potential transport model that could be used in the delivery of autonomous vehicles, arguing that delivering autonomy through car club vehicles would help the transition to shared, connected and autonomous vehicles (CAVs), as “Londoners will see vehicles as a service rather than a possession to own” [16] (p. 23), a view upheld by the likes of Shaheen, et al. (2018) and The Economist (2016) [2,3,17].

According to Katzev (2003), the concept of car clubs is based on the “distinction between automobile access and ownership” [18] (p. 68). Car clubs can therefore be recognised as an example of what Rifkin (2000) first termed ‘the age of access’—a world that is moving away from market-based transactions in favour of network relationships [19].

These network relationships rely on technology for their delivery and operation and, as a result, it is possible to maintain that access-based transport and technology are complementary. As Cohen and Kietzmann (2014) explain, it is the ubiquity of the internet and associated information and communication technologies that make sharing on a large scale possible [20].

Such is the importance of technology in enabling car clubs, that its investigation and reporting within academia is widespread. Both Le Vine et al. (2014) and the Transportation Research Board 2016 Annual Report have described how technology enables ‘disruptive’ modes of transport, citing car clubs specifically [15,21]. Evidence from the literature has also suggested that technology facilitates lower transaction costs, aids the management and payment of services, and helps identify and locate a vehicle to hire, as well as making it possible to unlock the vehicle without the need for keys. In addition, technology aids the service provider by reducing the costs of delivery, as vehicles can be tracked, fuel levels assessed and the quality of driving monitored [4,5,15].

Further evidence of the relationship between technology, car clubs and indeed sustainability has been observed in the roll out of electric vehicles (EVs) throughout car club fleets. A Vulog (2019) white paper explained that car clubs have been early adopters of EVs because their fleets are well positioned to accommodate the vehicles if a suitable infrastructure is in place, as often car clubs partner with manufacturers and therefore receive the newest and most environmentally friendly fleets first [22]. This, teamed with the expansion of the ultra-low emission zone (ULEZ) in London in October 2021, may well favour car clubs, with the majority of fleets in London already meeting the criteria to operate within the ULEZ.

Briggs (2014) also considered the opportunity that car clubs present in aiding the delivery of a wider transportation package [14]. However, for this to come to fruition a combination of technology-led integration and a willingness to promote car clubs as one of the city’s key mobility options would be required. This example represents a tentative nod towards a new transport mobility solution commonly called Mobility-as-a-Service (MaaS). As Nikitas et al. (2017) observed, the future of urban mobility may not be about creating and adapting to new, transformative, and disruptive modes of transportation or vehicles but instead about innovating with regard to the ways in which existing transport is used [23]. They argued that shared use models, such as car clubs, could be viewed as catalysts that facilitate the growth of MaaS by replacing privately owned transportation with personalised mobility packages that give access to multiple travel modes on an ‘as-needed’ basis, exploiting the riches of modern information and communications technology (ICT) [23].

For the world of transport and mobility, the shared economy has resulted in disruptive and exciting changes to transport offerings. Advocates of the shared economy have identified inefficiencies in current operations and have sought to upheave ‘normality’ by creating transport provisions that maximise efficiency and provide on-demand access through ‘sharing’ rather than private ownership. The transport-based shared economy has also benefited from shifting societal ideologies that stem from a growing social desire to be more environmentally friendly and economically savvy [7,24].

When considering the role of the sharing economy in the context of car clubs where monetary payment is commonplace, it is important to reflect on the work of academics such as Belk (2014) [25], Frenken and Schor (2017) [26] and Ranjbari et al. (2018) [27]. They have argued that, within the car club ecosystem, the transaction tends to result in financial benefit for at least one of the parties, and therefore car clubs should be categorised accordingly [25,26,27]. Thus, they suggested that ‘access’ would be a more suitable term to adopt, enabling money to be detached from the sharing transaction, and instead transforming it into an exchange of commodities [28].

Eckhardt and Bardhi (2015) build upon this construct by discussing the impact that monetary transactions have on the ideology of the sharing economy [29]. In areas of the transport industry such as car sharing, which can be recognised as part of a market-mediated economy, there is a strong case for claiming that in fact it is no longer sharing that is taking place; rather, consumers are paying to access someone else’s goods or services for a particular period of time. The resultant economic exchange means that consumers are seeking utilitarian, rather than social value. Developing this understanding further, it seems plausible to suggest that car clubs could be reallocated from the broader ‘shared economy’ definition into a more specific access-based consumption branch of the construct. In addition, it is worth noting that Bardhi and Eckhardt (2012) described ‘car sharing’ as a type of access-based consumption rather than sharing, whereby the former is defined as “transactions that can be market mediated but where no transfer of ownership takes place” (Bardhi and Eckhardt, 2012: 881) [7]. Similarly, Schaefers et al. (2016: 571) defined access-based consumption as “market-mediated transactions that provide customers with temporally limited access to goods in return for an access fee, while the legal ownership remains with the service provider” [30].

Le Vine et al. (2014) highlighted the suitability of the term ‘access’ and unbefitting nature of the term ‘sharing’ in this respect:

“Car sharing sits within the emerging class of ‘mobility services’ that draw on modern technology to enable access to car-based mobility without the consumer owning the physical asset (a car).”[15] (p. 3)

In this case, the definition relies on the term ‘access’ to explain the exchange taking place. From the user’s perspective, payment is made in order to access the vehicle for their own personal use, and interaction with any other user (i.e., sharing) is highly unlikely.

3. Case Study

London is a city that is brought to life by technology: a city made mobile by the countless transport models that serve the millions of commuters, tourists and residents who travel throughout it every day. In this ever-evolving climate, there is a growing demand and expectation placed on transport providers to deliver the most suitable, time-efficient, economically advantageous and hassle-free methods of travel possible. This has resulted in the highly competitive market of public and private transport modes currently available to people across the city.

The excitement generated around mobility in London makes it an interesting city for assessment, particularly given that car club growth in the capital has arguably been restricted by the geographical construct of boroughs, into which the city is divided, which has made the development of a citywide delivery mechanism almost impossible. As a result, there is a significant desire from policymakers to better understand the wider implications of car clubs in London [31].

In addition, London offers a wealth of data and analysis that makes it an attractive city for assessment. A recent Carplus Annual Survey (2017) revealed that there were eight car clubs operating in London, with around 193,500 members in total [32]. As of 31 March 2018, the revised figures suggested the city’s car clubs had witnessed further growth, with a total of 245,000 members and 2636 vehicles calculated (Information obtained via email correspondence (18 July 2019) with the Chief Executive of COMO UK). These figures constitute an increase from the 161,172 members recorded in 2011, representing a growth of approximately 20% to 2017. In 2020, the Annual Survey [33] saw the results impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic [34,35]. The report suggested a growing fleet size (3886 vehicles) with 565,505 members (a 130% increase), of which 189,275 had used a service within the last 12 months, highlighting the infrequency of use by members (69% used the service less than 5 times a year).

While this figure appears impressive at first glance, by comparison with other European cities, London’s car club growth is relatively low. For instance, it was reported that the German market grew by over 1.5 million members from 2011 to 2017 [36]. Such disparities, in spite of a relatively similar base membership in 2011, would suggest that the delivery of car clubs in the London context has, so far, not reached its potential, and is perhaps limited by several factors that have restricted their uptake in the city. This analysis therefore seeks to understand some of these limitations and identify how London should progress its car club strategy in order to maximise the benefits that car clubs can create for its citizens.

4. Methods

In an attempt to answer some of the questions posed in the literature review, and to contribute new material to this subject area, a mixed-methods approach was adopted. According to Creswell et al. (2003), mixed methods studies involve the collection and analysis of both quantitative and qualitative data in a single study [37]; the data can be collected concurrently or sequentially and then integrated at one or more stages of research. This approach has been referred to by academics as the third paradigm for social research; a natural complement to traditional methods whose usefulness has become more limited [38]. The mixed-methods approach was selected for this research, as it facilitates the creation of a more complete and nuanced picture [39].

The quantitative analysis obtained from a car club member survey provides a strong evidential base to offset, and strengthen, the limitations of qualitative interviews with a few industry specialists. Conversely, qualitative, in-depth interviews with the aforementioned industry specialists offer a level of detail with which to contextualise the quantitative data. A secondary data set was chosen for this analysis, as it allowed the researchers to access information than could have otherwise been obtained through primary methods. To this end, Vartanian (2011) argued the case for the use of secondary data, citing the comprehensiveness offered as an important factor for its use [40]. In the case of this analysis, the secondary data set analysed was obtained from London Councils, a city-wide cross-party organisation representing London’s 32 boroughs and the City of London. Given that this dataset has been used to inform the annual Carplus surveys (2015–2018), it was deemed suitable for carrying out car club analysis in Greater London. The quantitative data consisted of 5898 survey responses comprised of six Excel spreadsheets, with each spreadsheet containing the raw data responses from a car club provider; the operators were Bluecity, Enterprise Car Sharing, Zipcar, DriveNow, E-Car and Co-wheels. The data set consisted of a set of questions that each operator sent to its members via email or app notifications, with London Councils acting as an intermediary to ensure the questions were consistent across all car club providers.

As of 31 March 2018, there were an estimated 245,000 car club members in London, with 2636 registered vehicles, according to COMO UK. The survey was issued to all car club members with an account, with 5898 choosing to respond; therefore, the data is limited, as the choice to respond is reliant on individual car club users. In light of this, it could be anticipated that respondents to the survey are those that are relatively active on the platform or felt that they had a specific reason to respond.

The quantitative analysis was undertaken using car club member surveys that were distributed to members of six car clubs in 2019. The data obtained was made available in its raw format, ready for analysis and interpretation; therefore, all of the analysis disclosed within this section of the report was undertaken by the researchers.

A breakdown of the number of respondents by operator is presented in Table 1, below.

Table 1.

Survey responses by operator (n = 5898).

For the qualitative aspect of this research, semi-structured interviews were chosen as the method of data collection, due to their versatility and flexibility [41], thus ensuring that the interviews, while maintaining a basic structure, were open to a degree of reciprocity between the interviewer and interviewee. This enabled the discussion to unearth as much information as possible from the participant through follow-up questions and open discussion [42].

The interviewees all had backgrounds within the car club industry in London, as detailed in Table 2, below.

Table 2.

Range of interview respondents identified.

For the qualitative analysis in this mixed methods study, a thematic approach was adopted. Thematic analysis is perhaps the most common method used within qualitative analysis and was described by Guest et al. (2011) as a method of analysis that focuses on identifying themes by describing implicit and explicit ideas observed within the data [43]. The method is particularly popular, as it is a fruitful approach for capturing the complexities of textual data.

Thematic analysis also allows the researcher to identify, analyse and report patterns (themes) that they observe within the data [44]. As a result, this method can often facilitate an insightful analysis and offer opportunities to find answers to research questions that other methods may not [44].

After undertaking the quantitative and qualitative analysis, the findings from both were combined for interpretation by identifying similarities and differences observed from each aspect of the research.

5. Findings

5.1. Quantitative Analysis

The quantitative data was categorised into respective boroughs, and it was then possible to collate the member responses from each operator to provide a wider overview of car club survey respondents who used the services in London, thus enabling a better understanding of the distribution of car club survey respondents across the city. Creating a dataset at this borough level in turn made the analysis of comparative datasets such as census data possible. Initially the census data obtained consisted of information on population density and car or van availability by borough.

To better understand the composition of the respondents and provide an overview of the demographic characteristics of car club users, some high-level analysis of their age distribution was carried out, presented below in Table 3. Only 1112 respondents provided information about their age in the car club survey.

Table 3.

Demographic characteristics—age groups (n = 1112).

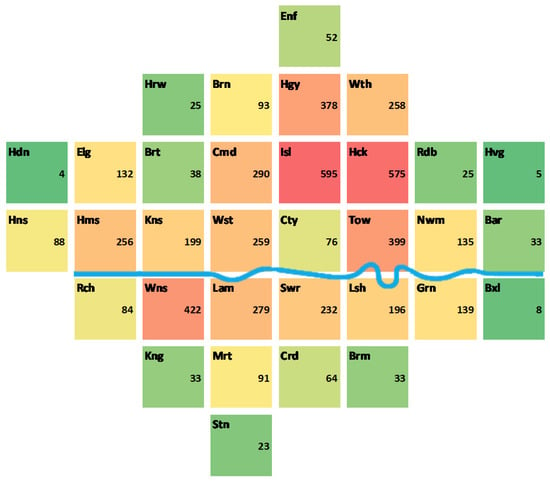

The distribution of car club respondents was translated into a cartogram map that represents the data in proportional squares, providing a depiction of the data that is particularly effective in highlighting car club users without consideration of the scale or size of the boroughs, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

A cartogram of London’s car club memberships. Cartographic Base Maps available from London Datastore (contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database rights.).

From Figure 1, it is apparent that, other than the City of London, central London boroughs generally have the greatest number of respondents. Baumgarte et al. (2021) also obtained a similar finding: car sharing activity is at its most intensive in the city centre, which is likely to be caused by the higher density of car club stations [45]. There is a particularly high level of membership in Islington, Hackney and neighbouring boroughs to the north as well as a cluster of high membership boroughs in the west of the city. The high membership levels to the west are interesting, as these boroughs are slightly more removed from what is recognised as London’s ‘core’, suggesting that factors other than centrality may have resulted in higher levels of respondents in these areas.

To test this theory, survey respondents were assessed against population density and the availability of cars and vans in each London borough. These two census data sources were selected as both have been identified within the literature as having an influence on car club usage: for example, Celsor and Millard-Ball (2007) provided an overview of neighbourhood characteristics identified in previous studies that are necessary for car clubs to succeed [46]. They suggested that, along with the presence of parking pressures and mixed-use development, car clubs operate best in environments where there is a high population density and where residents have opportunities to live without a car [46].

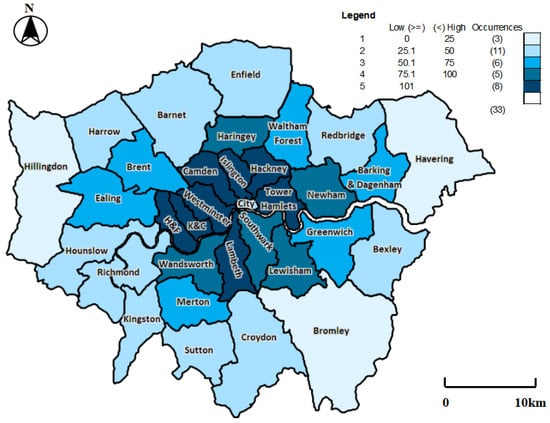

The census data sources were converted into thematic maps to see if there were any obvious geographical similarities between the population density of London and the location of survey respondents or the availability of cars and vans and the location of respondents in London.

Figure 2 shows that population density in London is greatest in the centre, which in its simplest terms reflects a city that exhibits many of the characteristics of the Burgess Model, albeit with a shift in the location of the most expensive housing to reflect changing societal desires to reside more centrally within London.

Figure 2.

London’s population density by borough. Data Sources: Thematic Base Maps available from London Datastore (contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database rights.) and Census (2011)–analysis conducted by the authors [47].

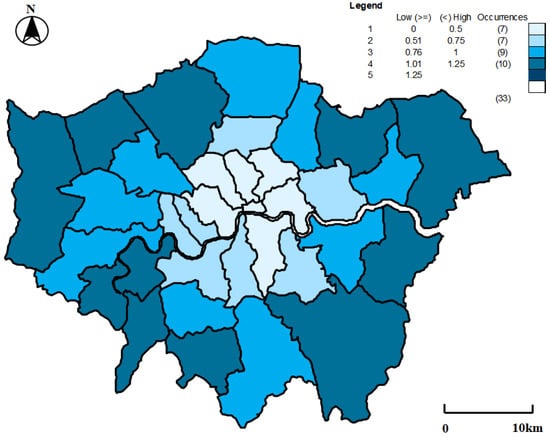

In regard to car ownership, an inverse pattern to that of population density can be observed, with car ownership levels being the lowest in central boroughs and highest in outer boroughs (Figure 3). This observation is widely accepted in the London context and reflects variations in the provision of alternative modes of transportation and the location of amenities.

Figure 3.

London’s car ownership levels by borough. Data sources: Thematic Base Maps available from London Datastore (contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database rights.) and Census (2011)–analysis conducted by the authors [47].

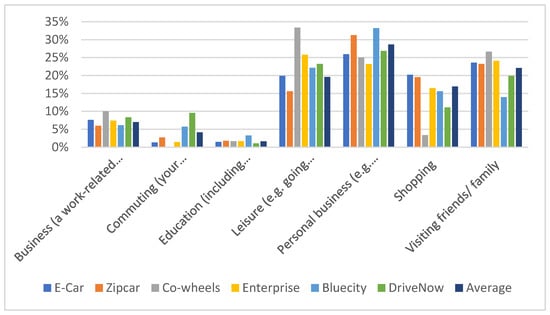

Data about the last journey made via a car club vehicle was broken down and is presented in Figure 4, showing both the responses by operators as well as an average for all car club member survey responses.

Figure 4.

Car club members most recent journey purpose.

Figure 4 illustrates that the majority of journeys are undertaken for the purpose of personal and leisure activities, as well as meeting friends or family. Personal journeys accounted for an average of 29% of all trips and were relatively consistent across all operators, with Enterprise members making the lowest proportion of personal trips (23%) and Bluecity members the highest (33%). By contrast, trips associated with work or education comprised a much lower percentage share for all operators, with business, education and commuting trips accounting for a combined 13% of the member responses. The consistency of responses across all the operators would suggest that the data is relatively reliable, and therefore it is plausible to assume that respondents tended to use vehicles to undertake more spontaneous trips, or trips where a car may be beneficial (i.e., transporting goods or people). With regard to the nature of the respondents’ journeys being made through car clubs, it is feasible to suggest that, for this group of people, there is a higher propensity for car club trips to occur outside of rush hour traffic, with the likely time and destination of journeys differing from the majority of commuting trips being completed in the capital.

The impact of car clubs on car ownership has been widely researched [48,49], with most academics concluding that car clubs reduce the number of private vehicles owned. Research from Cervero, Golub and Nee (2007) provides a relevant example: their findings for the San Francisco area concluded that 29% of carshare members had got rid of one or more cars, and 4.8% of members’ trips and 5.4% of their vehicle miles travelled were in car share vehicles [50]. Such findings suggest that car ownership among car club members in London would be expected to reduce significantly during their period of membership, which did indeed turn out to be the case. We acknowledge that while other factors may also have played a part in this reduction, it is fair to assume that car clubs did play a role in reducing the number of vehicles owned, either by providing a step change away from private ownership complemented by alternative modes (i.e., public transport) or as a more direct replacement for private vehicle use, although this could be examined empirically in further research.

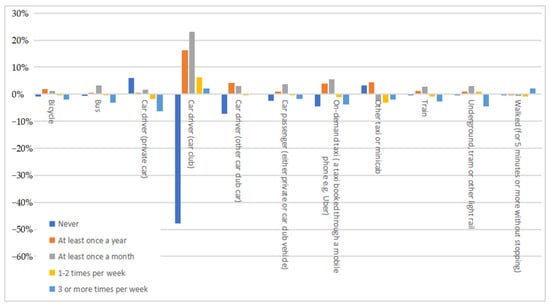

The final piece of quantitative analysis sought to identify what impacts car clubs have had on respondents’ use of other transport modes, with the results presented in Figure 5. For the survey respondents, the greatest impact of joining a car club was found to be the use of car club vehicles, with the amount of people who have ‘never’ used a car club reducing by 48%, as would be anticipated. However, the most interesting observation regarding the impact that membership has on car club use is that the greatest increases took place in the ‘once a year’ and ‘once a month’ categories, increasing by 16% and 23% respectively. Increases in these categories, rather than the ‘1–2 times a week’ (6% increase) or ‘3 or more times a week’ (2% increase), suggest that car club journeys tended to be infrequent trips undertaken to fill gaps in cases where other travel modes are less convenient.

Figure 5.

Impact of car club membership.

With regard to the use of other transport modes, for the survey respondents, the impact of becoming a car club member was generally relatively minimal. The impact on travel as a private car driver was an increase of 6%, with 266 respondents stating they have ‘never’ driven a private vehicle in the last 12 months, and a reduction of 6% (315 responses) in the number who have driven three or more times in the last 12 months. In the case of public transport trips, there was a reduction of 3% (98 responses) in the use of buses for journeys made three or more times a week while train journeys reduced by 2% (104 responses). However, these are relatively minor reductions and do not suggest that car clubs have a significant impact on the respondents’ use of public transport: rather, users were more open to various travel options and so perhaps spread their journeys more widely over a range of modes. Pertinently, research from Martin and Shaheen (2011) found that, on the one hand, car sharing decreased the use of buses and railways by quite a few participants [51]. On the other hand, many participants increased their use of other travel modes, such as walking, cycling and carpooling [51].

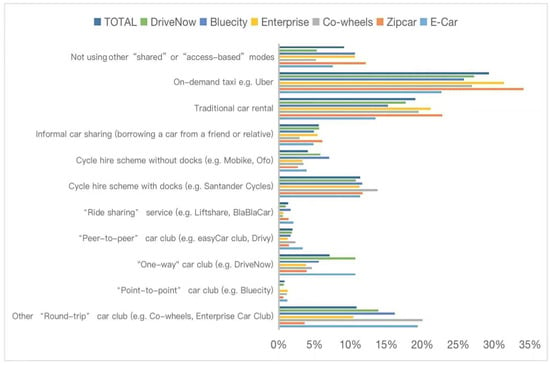

To complement this analysis, we also explored whether respondents used other forms of ‘shared’ mobility. A summary of the analysis is presented in Figure 6, which shows that 91% of the respondents had used one of the modes of transportation listed, suggesting that users appear receptive to using ‘shared’ or ‘access-based’ modes of transportation. Such findings are not conclusive; however, the evidence provides a strong case for suggesting that using car clubs could act as an enabler or catalyst in creating a mindset change towards access over ownership. This research advocates that London should capitalise on this shifting mentality by ensuring the combination of transport modes available can rival car ownership in terms of ease of use and cost. If a mechanism can be found to do so, the propensity to forgo a private vehicle will be increased, and the benefits to the city, operators and governing bodies will be maximised. Interestingly, at the time of writing, E-scooters are being trialled in London, in partnership with local authorities, highlighting a shift in mentality involving a willingness to trial and create suitable policy and regulations for access-based modes.

Figure 6.

Car club members’ use of other ‘shared’ modes of transport.

5.2. Qualitative Analysis

To complement the quantitative analysis, a series of interviews were undertaken with industry experts. The process followed a thematic framework that was applied to an inductive reasoning approach.

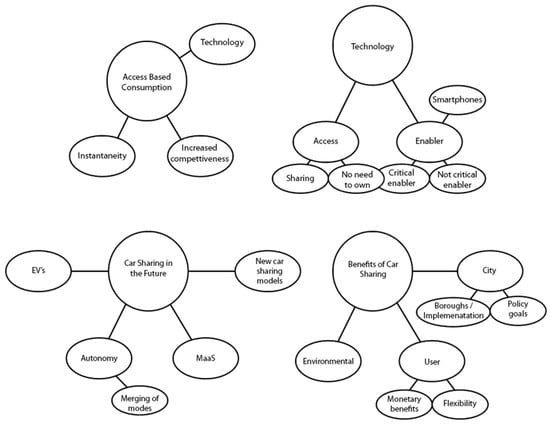

The methodology established four key themes from the interview transcripts. Figure 7 represents the four key themes visually, with the sub-themes and relationship between each also shown in the diagram. The qualitative findings from each of these themes are discussed in turn below.

Figure 7.

A thematic framework—the four themes (developed from Braun and Clarke (2006) [52]).

5.2.1. Benefits of Car Clubs

When thematically reviewing the responses provided by the interviewees with regard to the benefits of car clubs, it was possible to broadly categorise them into three sub-themes that reflected the main beneficiaries of the service, namely the user of the service, the city and the environment.

From a user perspective the respondents highlighted the economic benefits of car clubs, explaining that they are more cost effective than private car ownership. A future mobility professor suggested that for users, the affordability and flexibility of car clubs as well as less bother resulting from the responsibility of owning and maintaining a car tended to be the main user benefits. In addition, representatives of car club operators described the benefits they believed their clients gained from using the service, focusing on how the service would cost the consumer less than private vehicle ownership as well as highlighting how car clubs have become a relatively hassle-free way to access a vehicle.

The identification of car sharing as ‘hassle free’ is an interesting insight, as this certainly has not always been the case and highlights a relatively momentous shift away from the clunky car club models of old. Moreover, it is noteworthy that, in light of improvements to the service provision, car sharing operators are, to some extent, willing to go toe-to-toe with the benefits of private vehicles in terms of ease of access and reduced hassle. The respondents recognised that currently private vehicle ownership still leads the way in this regard, as the following statement confirms:

“Private vehicle ownership does facilitate a level of on demand use that is rivalled, but not matched by car sharing.”(Zipcar UK, May 2019)

From a city perspective, the benefits of car sharing are a hot topic that remains open to debate. Advocates of car sharing argue in favour of its ability to reduce private car ownership and the associated benefits of efficiency and reducing emissions, congestion and space saving (parking demand). However, there are difficulties in assessing the benefits of car sharing in London, as one interviewee explained:

“These are not the benefits, but the potential benefits, because what may work in one area may not work in another place. In theory, car sharing could help local boroughs achieve the local transport strategies, and could help achieve the mayor’s transport strategy (MTS), and there are a number of different goals that are part of a subset of that. Now again it is not always the case, especially in inner London where active travel (walking and cycling) and public transport are particularly strong. Here putting people into cars is precisely the opposite of what we want to achieve. So, while in theory, it could reduce car ownership, and again we should talk about different models of car sharing, because different models have different effects on the market, in practice it only works in certain areas. So, I think striking the right balance is the key thing here.”(London Councils, April 2019)

This response highlights the complexity of delivering car sharing in London: there is no ‘one size fits all’ solution, and the benefits are likely to vary depending on the location. This complexity is exacerbated further by London’s geographical landscape in terms of policy and governance, as the city comprises 32 London boroughs and the City of London, all of which have their own governance strategy and requirements. As a Zipcar representative explained:

“London presents a difficult market to enter as each of the 33 London Boroughs has its own criteria for entry, this is particularly restrictive for the free-floating offering. (Zipcar are in almost all of the boroughs with their point-to-point offering, but only 10 with flex).”(Zipcar UK, May 2019)

Some boroughs are more supportive of car sharing and view it as a viable alternative to private vehicle ownership, a statement supported by an interviewee representing a Central London Borough, who explained that

“… there are complexities in London with 32 boroughs, the City of London and TfL all being highway authorities with their own jurisdiction… but most boroughs are supportive. I think some car club operators might argue for a simpler system, but they are also not necessarily willing to implement in London at the rate they might elsewhere, because London is expensive and not all of London is likely to be profitable for them.”(Central London Borough, August 2019)

By contrast, some boroughs, particularly in areas with good public transport and levels of active travel, may view car sharing as being detrimental to their ambitions at a borough level.

As a result, the delivery of car sharing in London has thus far been fragmented:

“Leading to piecemeal, sub-optimal, outcomes across London.”(Zipcar UK, May 2019)

From an environmental perspective, the benefits of car sharing can be viewed in terms of the individual and the city. Firstly, with regard to the user, the interviewees explained that growing environmental awareness and concerns, alongside a diminishing love affair with private vehicle ownership, has given rise to increased interest in car sharing. People now recognise that using a vehicle sporadically and only when necessary is more sustainable than owning and using a car that is idle for much of the time. Interestingly, both ShareNow and London Councils also noted how the sharing of vehicles presents an opportunity for the public to

“Trial and use electric vehicles and decide whether they would want one in future.”(London Councils, April 2019)

5.2.2. Technology

“Technology has been the starting point for the growth in car-sharing, the development of mobile applications and 3, 4, and 5G makes booking, paying and accessing vehicles instantaneous and easy to complete.”(Zipcar UK, May 2019)

In this response, many of the key sub-themes identified under the broader technology umbrella can be observed, namely, the role of smartphones in enabling journeys in car sharing vehicles, thus removing many of the barriers to entry and allowing a much more demand-responsive service, an idea explored by another interviewee, who explained:

“People are used to running their lives through their phone, they like the spontaneity of being able to book things instantly and have access to information. The way it’s facilitated means you can access a new vehicle for only a few pounds.”(Steer and COMO UK Chair, June 2019)

One of the key sub-themes explored under the topic of technology was the role it played in the uptake of car sharing, with another COMO UK representative remarking that technology, facilitated through mobile platforms, is an enabler for car sharing. However, the discussion about the extent to which technology has enabled car sharing was contested and debated by the respondents. For example, a future mobility professor agreed that technology is no doubt an enabler of delivery, but he challenged whether it was the critical enabler. This response could be interpreted in several ways and suggests that perhaps other factors have also encouraged a greater uptake of car sharing. Such an assumption would tend to align with the qualitative analysis undertaken in this report as several themes were identified, in addition to technology, as having facilitated a rise in its use and popularity.

5.2.3. Access-Based Consumption

Questions were therefore posed to the interviewees with the intention of gaining an understanding of their views about the relationship between car clubs, the sharing economy and access-based consumption.

Initially respondents debated the sharing economy in the context of car clubs and more generally. Interestingly, respondents with an academic background challenged the term ‘sharing economy’. A future mobility professor stated that he felt that “The sharing economy is, to some extent, another hyped phenomenon”, while a consultant described the premise as a “cuddly name for a new shiny business model”. In both instances, the respondents considered what is being shared, with the COMO UK Chair asking: “Are you sharing the asset or are you sharing the trip?” A similar view was expressed by the future mobility professor, suggesting that in the UK, there is not a strong sharing mobility culture, which explains why most people in London choose not to share an Uber, even though the model to do so (UberPool) is available.

In the context of London, the complexities of the city make it difficult to generalise about the relationship between car sharing and other modes of travel, as explained by the future mobility professor:

“This partly depends upon whether one is referring to central or outer London. However, car sharing is in any case a better alternative to privately owning a car (or owning more than one car). At the same time, the choice may not be between owning a car or joining a car club, but in fact owning a car or not having access to a car for one’s own use. ‘Uberisation’ suggests an even more flexible means of tripmaking by a car from a user perspective. Meanwhile there are clearly other modes (particularly for shorter trips) that are able to compete with the car (whether privately owned, leased or shared)—micromobilities as well as public transport.”(April 2019)

While agreeing with the access-based sentiment, a representative of car club operators provided an interesting perspective from the operator’s viewpoint. He explained that it is “absolutely essential for the running of the system that you have users who are in the mindset where they want to share the resource, whether they are paying for it or not”. In creating this environment, the DriveNow representative explained that a car club is more likely to survive and operate effectively if people buy into the system rather than abusing it. He pointed out that DriveNow (ShareNow):

“… couldn’t provide for your mobility needs on its own, it is about all of the services becoming available and accessed through your phone that makes car clubs and car sharing more of a proposition because if you cannot find a DriveNow vehicle you may get a bike, Uber, train, instead, or vice versa. It is all these different products. A private car can offer every trip function, while other modes cannot, but together hopefully we can have a proposition that’s as convenient as owning a private car.”(April 2019)

Such a sentiment provides an interesting point for consideration as it highlights the operator’s stance in not offering the complete product, but instead suggesting that their vehicles require the support of other modes in order to create a complete transport offering. This appears to be consistent with the quantitative analysis, which shows respondents continuing to use public transport and active modes of travel, as well as other forms of shared mobility.

5.2.4. The Future

When considering how car clubs may be delivered in the future, the consensus was that the primary existing models (flexible and round trip) will continue to operate and grow in the city. Respondents explained that these models tend to serve different purposes, and therefore there is scope for both to grow simultaneously in the city.

There was considerable interest in the potential hybridisation of flexible and ‘back-to-base’ models that would create a ‘back to area’ style model. A representative of a central London borough explained that this model would be provided: “without dedicated car-club only bays, but with a defined ‘base’ area to which the car must be returned (e.g., a street or small cluster of streets)”. This merging of models is an interesting proposition, as it would appear to benefit all parties involved. For the user, a ‘base’ model provides better opportunities to park a vehicle, while the local authority and service provider benefit as neither need to consider the provision of any hard infrastructure.

EVs were continually cited as a key component of London’s future transport, with car clubs identified for their ability to assist in achieving governmental targets by providing newer fleets in a shorter timeframe. For operators, the commitment and opportunity to deliver EVs in shorter timeframes was cited as a key motive and opportunity for growth. A Zipcar UK representative explained that Zipcar has made a commitment to deliver zero emission fleets by 2025, a timeframe much shorter than would be possible for private vehicles. Meanwhile the DriveNow and ShareNow representative gave his thoughts on the potential benefits of EVs:

“At DriveNow we are being pushed to use more electric vehicles because I think car sharing could have an important role to play in allowing people to access, use and understand electric vehicles and electric charging. With ULEZ coming in, if you own a car, you can come and try out one of our electric vehicles and see what it’s like and how it works, and by having this opportunity to use one instantly and not worry about the cost of getting a new electric vehicle might push the needle in favour of giving up a private car entirely. I think electric vehicles for car sharing is the next frontier that’s going to make them positive policy tools, for example we have 20% electric vehicles already, compared to what like 2% in the UK.”(April 2019)

Such an ambition highlights a key benefit of car clubs for London in the future; they offer a degree of adaptability that can be utilised to achieve policy ambitions for the city, such as reducing harmful emissions. However, Zipcar were not alone in voicing concerns over the provision of charging infrastructure in the city, suggesting that, as an operator, Zipcar would be positioned to meet their targets, but only if the level of charging infrastructure in London was to increase significantly. Conversely, however, there is an ongoing debate about who should provide this infrastructure, as a ShareNow representative confirmed, for Round Trip models: “It tends to be more difficult to get electric vehicles into the fleet because you tend to have dedicated parking so need dedicated charging points.” (April 2019)

The challenges and opportunities facing operators were further elaborated by the COMO UK chair, who noted:

“… what Zipcar and DriveNow are doing is charge when they need it, those vehicles are typically used for shorter journeys so need to be charged less often, I think we will move towards inductive charging with car-sharing presenting a potential testbed for them. Having an urban fleet that does a lot of mileage is a great way to test it, but then again you would not necessarily need a specific space, you may electrify a street instead. The challenge with EV charging for car sharing is that you want that facility to be available to everybody because they won’t be charging the whole time, they just need to be charged when people need to use them.”(May 2019)

6. Discussion

The quantitative analysis uncovered a clear relationship between population density and car sharing, which corresponds with findings from the likes of Celsor and Millard-Ball (2007) [46]. However, the focus on providing memberships in the ‘most suited’ boroughs has resulted in an imbalance with regard to car club provision, a limitation identified in the qualitative analysis that has yet to be addressed. From a critical perspective, it could be argued that both the providers and facilitators are at fault for this imbalance; respondents noted that both parties must recognise that a comprehensive provision would be of greatest benefit to all concerned. Car clubs would benefit from a greater catchment area and provision, offsetting any lost profits from serving potentially less profitable boroughs, while local authorities would benefit from offering better travel options for residents. To achieve this goal, respondents felt that better engagement between policymakers and operators would be required, fuelled by full transparency between all parties.

The complexities of the London boroughs and their associated policy management was a commonly recognised limiting factor, with all interview respondents in agreement that a more coordinated approach would benefit car club growth in London. However, more needs to be done to encourage the provision of services in outer boroughs where alternative modes are less forthcoming, and car clubs would be required to go toe-to-toe with car ownership. Based on the findings of the study by Loose et al. (2006), it is necessary to strengthen the cooperation between car club operators and local governments [53]. One of the difficulties that car club operators face is that they need to obtain permission from every borough where they intend to operate. Moreover, each borough has different standards for obtaining consent. Through a cooperative relationship, car clubs could be given licenses to operate in different boroughs, thus improving car sharing efficiency. The local council should regard the car club as a partner within the sustainable transport system. As Loose et al. (2006) recommended, municipalities should highlight the benefits of car sharing in terms of reducing motorised traffic and promote it, politically and practically, as a sustainable transport mode [53].

The literature review considered the debate surrounding the impact of car clubs on other forms of transportation, which was explored further during the interview process. Respondents raised concerns regarding the impact that car clubs, specifically flexible models, have on sustainable travel options. Operators appeared willing to support the development of an evidence base to aid understanding of car clubs but argued that currently there is not a consistent appetite for trialling and learning about the mode in London. Other interviewees, however, suggested that operators did not always provide the requested data to every borough. Such contrasting statements suggest that an impasse between the public and private bodies has been reached, with public bodies unwilling to trial or invest in a car-based mode of transportation due to a lack of evidence, thus making it difficult for operators to work efficiently. Interviewees felt that this lack of support and funding discouraged operators from sharing significant data or operating in less profitable boroughs, and this combination has resulted in a continuation of the piecemeal car club offering that currently prevails in London.

This research also sought to contribute to a greater understanding of the relationship between car clubs and sustainable travel. The quantitative analysis revealed that car club members only slightly reduced their use of sustainable travel modes. These findings were contrary to those of Shaheen, Totte and Stocker (2018), who suggested that becoming a car club member in London does not significantly reduce the use of other sustainable modes [3], a view advocated by Birdsall (2014) [12]. We argue that this finding is one that could be viewed positively by all parties, providing encouragement to introduce car clubs more widely.

As acknowledged from the outset of this paper, a key focus of the study has been to understand the impact that the growth of the sharing economy, and more specifically access-based consumption, has had on the implementation of car clubs in London. Bardhi and Eckhardt (2012) suggested that in a contemporary society, ownership is no longer the ultimate expression of consumer desire [7]; in its place, they suggest, are models of access that are gaining popularity by utilising the internet [7].

This analysis therefore sought to investigate whether shifting consumer characteristics could be observed in the responses of car club members and interviewees, a cohort of users and experts who have engaged with access-based consumption on either a conscious or sub-conscious level.

From a qualitative perspective, respondents also cited smartphones and technology more generally as key enablers in the use of car clubs. Therefore, the findings of this analysis seem to agree with the observations made by Bardhi and Eckhardt (2012) and the analysis of the quantitative data [7].

Although such findings are not conclusive, the evidence from both the quantitative and qualitative analysis combined provides a strong case to suggest that using car clubs could act as an enabler or catalyst in creating a mindset change towards access over ownership. We therefore argue that London should capitalise on this shifting mentality by ensuring that the combination of transport modes available can rival car ownership in terms of ease of use and cost [54]. If it can do so, the propensity to forgo a private vehicle will increase, and the benefits to the city, operators and governing bodies will be maximised [55].

7. Conclusions and Recommendations

There is a comprehensive wealth of literature concerning the benefits of car clubs based on a wide range of case studies. However, there continues to be a lack of evidence concerning car clubs and their impact in the context of London. Researchers [14] and interviewees from both a public (London Councils) and private (DriveNow) perspective have suggested that evidence is limited concerning the impact of car clubs on public transport, particularly in the case of newer models.

Our research has sought to bridge this gap through a mixed methods approach that involved complementing interviews with industry experts with evidence from the most comprehensive car club survey for London in order to answer some of these questions. Such evidence has revealed car clubs to be beneficial in reducing car ownership levels (38% reduction), with minor impacts on the use of sustainable travel modes. The research did not find any evidence to suggest that new models of car clubs such as flexible car sharing have a greater impact on reducing travel by sustainable modes, instead uncovering a trend among members for using other access-based modes of transportation.

This paper also makes a significant contribution to furthering existing knowledge by considering how access-based consumption and technology have influenced car clubs, as well as adopting a forward-looking perspective by considering what the implications may be in the future. This analysis addresses an area of transportation that is growing in popularity, categorised as a form of disruptive transportation; such findings are important for London as they provide a basis for the city to plan effective delivery for the future. Most interestingly, the analysis highlights how the potential of car clubs in London is not currently being realised.

The outcomes derived from this study have several important policy implications. First, given that this study supplied evidence that car club membership is more likely to significantly decrease the use of privately-owned vehicles (although it depends on, for instance, whether users live in inner or outer London, as well as their local level of public transport provision), car club operators, policymakers and practitioners should implement a set of development steps designed to fully integrate car sharing into a sustainable transport system, which could help reduce car usage to some extent. Second, in order to promote car sharing in London, car club operators should improve the quality of car sharing services, publicise car sharing as an innovative and sustainable mobility service to a greater extent and become more aware of potential clients so that they can transform them into real car club users. Third, it is necessary to strengthen cooperation between the stakeholders involved, including car club operators, local governments/councils and potentially third parties. Only then can there be a genuine opportunity to turn the millions of potential customers into actual customers. Local councils should regard car clubs as a partner in the sustainable transport system. Moreover, they should also implement relevant policies and strategies to facilitate the development of car sharing, such as unified operating permission standards for car clubs in different areas and setting up reserved parking spaces for car club vehicles in public streets. Potentially third parties should commit to transparency in future investments, mergers and acquisitions. Fourth, the development of mobile applications used in car sharing should keep pace with the rapid advancement of technology. Producers of mobile applications should aim to make them easy and convenient for customers to use, promoting the benefits of car sharing services and attracting a wider pool of potential clients. For example, customers could select vehicles from different car club operators using smartphones. Fifth, it is worth noting that, as the development of car clubs in the UK is still in its infancy, EV charging infrastructure should be provided as the key to supporting and promoting the use of EVs by car clubs. However, in light of the existing difficulties car club operators face in terms of deployment, it is unrealistic to expect car clubs to solve the EV infrastructure problems in the short term. Therefore, stakeholders, including local authorities, car clubs and potentially third parties, should consider how a fair financing model could be set up. Moreover, stakeholders should discuss and determine whether only car club members would be entitled to use the charging points or if they should be accessible to all.

This study has several limitations. First, the research sample only contained car club users of the six participating car clubs. Thus, future studies could include additional car clubs as well as investigating potential car club users and former car club users whose memberships have lapsed. Second, given that this research has not investigated the profile of car club users and key non-car club groups (e.g., regular public transport commuters) in any detail, a comparison of car club users and users of other types of public transport could be undertaken to assess the distribution of transport options in future studies. Third, to take the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on travel behaviours into account [35,56,57], future research could investigate the effects of COVID-19 on car sharing, such as people choosing to revert to using private vehicles and other individual modes of travel due to health concerns.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.H. and M.C.; methodology, A.H. and M.C.; software, A.H.; validation, A.H., M.C. and Q.L.; formal analysis, A.H.; investigation, A.H.; resources, A.H., M.C. and Q.L.; data curation, A.H.; writing—original draft preparation, A.H. and M.C.; writing—review and editing, A.H., M.C. and Q.L.; supervision, M.C.; funding acquisition, M.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is partly funded by the EPSRC (EPSRC Reference: EP/R035148/1), the NSSFC (Project No. 21CSH015) and the NSFC (Project No. 51808392).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the conclusions of this article can only be made available for academic research.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the editor and the anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments to improve the initial manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- COMO UK. Car Club Annual Survey for London. 2018. Available online: https://como.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/London-Car-Club-Survey2017_18.pdf (accessed on 25 March 2021).

- Shaheen, S.; Cohen, A.; Jaffee, M. Innovative Mobility: Carsharing Outlook; Research Reports, Working Papers; Institute of Transportation Studies, UC Berkeley: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Shaheen, S.; Totte, H.; Stocker, A. Future of Mobility White Paper; Research Report, Working Paper; Institute of Transportation Studies, UC Berkeley: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Henten, A.; Windekilde, I.M. Transaction costs and the sharing economy. Digit. Policy Regul. Gov. 2016, 18, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namazu, M. The evolution of carsharing: Heterogeneity in Adoption and Impacts. Ph.D. Thesis, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Department for Transport. Future of Mobility: Urban Strategy; Department for Transport: London, UK, 2019.

- Bardhi, F.; Eckhardt, G.M. Access-based consumption: The case of car sharing. J. Consum. Res. 2012, 39, 881–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mounce, R.; Nelson, J.D. On the potential for one-way electric vehicle car-sharing in future mobility systems. Transp. Res. A-Pol. 2019, 120, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metz, D. Peak car and beyond: The fourth era of travel. Transp. Rev. 2013, 33, 255–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Marshall, S.; Cao, M.; Manley, E.; Chen, H. Discovering the evolution of urban structure using smart card data: The case of London. Cities 2021, 112, 103157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NOMIS. Official Labour Market Statistics and Online Portal for UK Census. 2019. Available online: https://www.nomisweb.co.uk/ (accessed on 5 November 2021).

- Birdsall, M. Carsharing in a sharing economy. ITE J. 2014, 84, 37–40. [Google Scholar]

- Shaheen, S.A.; Cohen, A.P. Growth in worldwide carsharing: An international comparison. Transp. Res. Rec. 2007, 1992, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Frost & Sullivan. Car-Sharing in London—Vision 2020. 2014. Available online: https://www.frost.com/news/press-releases/frost-sullivan-vision-2020-sets-framework-exponential-growth-car-sharing-market-london (accessed on 6 August 2021).

- Le Vine, S.; Zolfaghari, A.; Polak, J. Carsharing: Evolution, Challenges and Opportunities; ACEA: Brussels, Belgium, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- London Assembly-Transport Committee. Future Transport: How Is London Responding to Technological Innovation; London Assembly: London, UK, 2018.

- The Economist. The Driverless, Car-Sharing Road Ahead. 2016. Available online: https://www.economist.com/business/2016/01/09/the-driverless-car-sharing-road-ahead (accessed on 6 August 2021).

- Katzev, R. Car sharing: A new approach to urban transportation problems. Anal. Soc. Issues Public Policy 2003, 3, 65–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rifkin, J. The Age of Access: The New Culture of Hypercapitalism, Where All Life is a Paid-For Experience; Penguin: Harmondsworth, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, B.; Kietzmann, J. Ride on! Mobility business models for the sharing economy. Organ. Environ. 2014, 27, 279–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Transportation Research Board 2016 Annual Report; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Vulog. EU CO2 Emission Regulations—How Carmakers Can Avoid Billions in Fines by Launching EV Carsharing. 2019. Available online: https://info.vulog.com/eu-co2-emission-regulations (accessed on 6 August 2021).

- Nikitas, A.; Kougias, I.; Alyavina, E.; Njoya Tchouamou, E. How can autonomous and connected vehicles, electromobility, BRT, hyperloop, shared use mobility and mobility-as-a-service shape transport futures for the context of smart cities? Urban Sci. 2017, 1, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cheshire, L.; Walters, P.; Rosenblatt, T. The politics of housing consumption: Renters as flawed consumers on a master planned estate. Urban Stud. 2010, 47, 2597–2614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belk, R. You are what you can access: Sharing and collaborative consumption online. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 1595–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenken, K.; Schor, J. Putting the sharing economy into perspective. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2017, 23, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjbari, M.; Morales-Alonso, G.; Carrasco-Gallego, R. Conceptualizing the sharing economy through presenting a comprehensive framework. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Belk, R. Sharing Versus Pseudo-Sharing in Web 2.0. Anthropologist 2014, 18, 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvard Business Review. The Sharing Economy Isn’t About Sharing at All. 2015. Available online: https://hbr.org/2015/01/the-sharing-economy-isnt-about-sharing-at-all (accessed on 6 August 2021).

- Schaefers, T.; Lawson, S.J.; Kukar-Kinney, M. How the burdens of ownership promote consumer usage of access-based services. Mark. Lett. 2016, 27, 569–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Vine, S.; Polak, J. The impact of free-floating carsharing on car ownership: Early-stage findings from London. Transp. Policy 2019, 75, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steer Davies Gleave. Carplus Annual Survey of Car Clubs 2016/17; Steer Davies Gleave: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- COMO UK. Car Club Annual Report London 2020. 2020. Available online: https://como.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/CoMoUK-London-Car-Club-Summary-Report-2020.pdf (accessed on 19 August 2021).

- Zhang, Y.; Cao, M. How will transit station closures affect Londoners? Focus 2020, 22, 52–53. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Cao, M.; Cheng, L.; Zhai, K.; Zhao, X.; De Vos, J. Exploring the relationship between the COVID-19 pandemic and changes in travel behaviour: A qualitative study. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2021, 11, 100450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DriveNow. Is London Playing Catch Up to the Changes in the Car Sharing Market? 2019. Available online: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/london-playing-catch-up-changes-car-sharing-market-james-taylor/?trk=portfolio_article-card_title (accessed on 5 November 2021).

- Creswell, J.W.; Plano Clark, V.; Gutmann, M.; Hanson, W. Advanced mixed methods research designs. In Handbook of Mixed Methods in Social and Behavioral Research; Tashakkori, A., Teddlie, C., Eds.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003; pp. 209–240. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, R.B.; Onwuegbuzie, A.J. Mixed methods research: A research paradigm whose time has come. Educ. Res. 2004, 33, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Denscombe, M. Communities of practice: A research paradigm for the mixed methods approach. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2008, 2, 270–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vartanian, T. Secondary Data Analysis; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kallio, H.; Pietilä, A.M.; Johnson, M.; Kangasniemi, M. Systematic methodological review: Developing a framework for a qualitative semi-structured interview guide. J. Adv. Nurs. 2016, 72, 2954–2965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, H.J.; Rubin, I.S. Qualitative Interviewing: The Art of Hearing Data, 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Guest, G.; MacQueen, K.M.; Namey, E.E. Applied Thematic Analysis; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V.; Hayfield, N.; Terry, G. Thematic Analysis. In Handbook of Research Methods in Health Social Sciences; Liamputtong, P., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 843–860. [Google Scholar]

- Baumgarte, F.; Brandt, T.; Keller, R.; Röhrich, F.; Schmidt, L. You’ll never share alone: Analyzing carsharing user group behavior. Transp. Res. A-Pol. 2021, 93, 102754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celsor, C.; Millard-Ball, A. Where does carsharing work? Using geographic information systems to assess market potential. Transp. Res. Rec. 2007, 1992, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ONS. 2011 Census Analysis: Method of Travel to Work in England and Wales. 2019. Available online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/employmentandemployeetypes/datasets/methodoftraveltowork (accessed on 5 November 2021).

- Le Vine, S. Strategies for Personal Mobility: A Study of Consumer Acceptance of Subscription Drive-It-Yourself Car Services. Ph.D. Thesis, Imperial College London, London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, E.; Shaheen, S. Impacts of Car2go on Vehicle Ownership, Modal Shift, Vehicle Miles Traveled, and Greenhouse Gas Emissions: An Analysis of Five North American Cities; Research Report, Working Paper; Institute of Transportation Studies, UC Berkeley: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cervero, R.; Golub, A.; Nee, B. City Carshare: Longer-term travel demand and car ownership impacts. Transp. Res. Rec. 2007, 1992, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, E.; Shaheen, S. The impact of carsharing on public transit and non-motorized travel: An exploration of North American carsharing survey data. Energies 2011, 4, 2094–2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Loose, W.; Mohr, M.; Nobis, C. Assessment of the future development of car sharing in Germany and related opportunities. Transp. Rev. 2006, 26, 365–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spurling, D.; Spurling, J.; Cao, M. Transport Economics Matters: Applying Economic Principles to Transportation in Great Britain; Brown Walker Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, M.; Spurling, J. Fundamental Concepts and Functions of Passenger and Freight Transportation in Great Britain; Brown Walker Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Song, X.; Cao, M.; Zhai, K.; Gao, X.; Wu, M.; Yang, T. The effects of spatial planning, well-being and behavioural changes during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Sustain. Cities 2021, 3, 686706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vos, J. The effect of COVID-19 and subsequent social distancing on travel behavior. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2020, 5, 100121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).