1. Introduction

Precise and reliable navigation technologies are fundamental to intelligent and high-performance transportation systems applications such as Advanced Driver-Assistance Systems (ADASs), Vehicle-to-Vehicle (V2V) plus Vehicle-To-Infrastructure (V2I) communication, lane-level navigation, and traffic monitoring [

1,

2,

3]. Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS), including the Global Positioning System (GPS), Globalnaya Navigatsionnaya Sputnikovaya Sistema (GLONASS), Galileo satellite navigation system (Galileo), BeiDou Navigation Satellite System (BDS), are integral and reliable technology to modern transportation applications, providing navigation solutions continuously and ubiquitously. Differential GNSS positioning (DGNSS) provides real-time solutions by applying corrections, which are pseudo-range (or phase-range) corrections (PRCs) and range rate corrections (RRCs) transmitted from a base station. When DGNSS uses carrier-phase measurements, the technique is known as real-time kinematic (RTK); whereas when it relies solely on code measurements, it is simply known as DGNSS [

4]. The DGNSS demonstrates meter-level horizontal root mean square error (RMSE) values [

5,

6]. In forested environments, RTK achieved horizontal positioning RMSE values of less than 50 cm [

7]. Additionally, the integration of RTK positioning with an Inertial Navigation System (INS) demonstrates a positioning accuracy of 3 cm when utilizing (BDS) [

8]. Different RTK-based georeferencing methods can achieve high photogrammetric accuracy without relying on ground control points (GCPs) [

9]. RTK positioning has been proven to enable a few centimeters of horizontal accuracy in unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) applications, making it highly suitable for precision mapping and geospatial data acquisition [

10,

11]. Therefore, differential positioning, particularly RTK, is the most favorable technique for transportation applications, either as a standalone method or integrated with systems such as INS, Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR), or Precise Point Positioning with RTK (PPP-RTK) [

12,

13].

The relative positioning (RP) technique, rather than transmitting PRC and RRC to the rover, determines the baseline vector between the base and rover, and, similar to DGNSS, can be implemented using code- or carrier-phase measurements through single, double, or triple difference methods [

4]. Unmodeled GNSS errors were analyzed, revealing greater impact over long baselines, strong L1–L2 correlation, and that they were mainly caused by atmospheric [

14]. Low-cost GNSS receivers can achieve meter-level horizontal accuracy using relative positioning over long baselines [

15]. Numerical algorithms have been developed to demonstrate the efficiency of relative positioning accuracy in real-time and post-processing for various applications [

16,

17,

18].

Towards low-cost precise navigation, the growing advancements in smart devices, such as smartphones embedded with GNSS sensors, have become increasingly significant, particularly following the Google I/O Conference, where access to raw GNSS measurements was made available [

19]. Mobile applications such as Geo++RINEX and GNSS Logger now allow users to directly extract these measurements in RINEX format [

20,

21]. The release of multi-constellation, multi-frequency GNSS smartphones such as the Xiaomi Mi 8, Huawei Mate 40, Google Pixel 9 Pro XL, and Samsung Galaxy S22 has paved the way for low-cost, high-precision positioning using consumer-grade devices, including the Xiaomi 11T module employed in this research [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26]. Smartphone-based RTK positioning has demonstrated accuracy ranging from centimeter to meter levels, making it suitable for various transportation applications across diverse environmental conditions [

27,

28].

This study evaluates the performance of carrier-based RTK and code-only RP solutions using single-frequency multi-GNSS data extracted from the Xiaomi 11T module employing different constellations scenarios for transportation applications. The rest of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 describes the carrier-based RTK and code-only RP GNSS mathematical model.

Section 3 describes the experimental setup, smartphone hardware, data collection, data quality, and processing approach.

Section 4 presents and analyzes the results.

Section 5 discusses the key findings and implications, and

Section 6 concludes the paper with a summary and suggestions for future research.

2. GNSS Mathematical Models

2.1. Carrier-Based RTK Mathiematical Model

A geodetic receiver (Trimble R4s) was positioned to be stationary and centering over a known base point (

A) and a smartphone (Xiaomi 11T) was moving over unknown points (i.e., rover

B). The base station observation equation at reference time

and observation equation of rover at time

can be expressed as follows [

4]:

The parameters and represent the carrier phase range, in meter, between the satellite s and receivers A and B, respectively; and are the geometric range between satellite and receivers A and B, respectively; and are phase-range biases that depend on both receivers (A and B) and satellite positions such as orbit errors and atmospheric refraction; represents the satellite-only-based phase-range biases such as satellite clock error; and are the phase-range biases based on receivers (e.g., receiver clock error and multipath) A and B, respectively; is the wavelength of the transmitted signal; and finally, and are the phase ambiguity for receivers A and B, respectively.

The phase-range corrections at reference time

(

) at base station (known) can be expressed as follows:

Base station

A transmits phase-range correction

and range rate corrections

) to rover

B. Therefore, phase-range corrections at rover

B can be predicted at time

t using the relation:

The term

represents the latency; higher accuracy is achieved when the latency is small. By applying the base station correction, the corrected phase range at rover

B can be expressed as follows:

By substituting Equation (2) and the phase-range correction according to Equations (3) and (4), respectively, Equation (5) can be rewritten as follows:

It can be noticed that the satellite-only-based phase errors canceled out. Also, for short baseline (in our case less than 5 km), the phase-range errors that depend on receiver and satellite position can be neglected. Thus, the corrected phase range at rover

B can be rewritten as follows:

2.2. Code-Only RP Mathiematical Model

The objective of relative positioning is the determination of the position of the smartphone (i.e., rover

B) with respect to the reference point (i.e., base

A), which is stationary, by determination of the baseline vector. Corresponding to the position vector of point

A (

) and

B (

), the baseline vector (

) relation can be expressed as follows [

29]:

3. Kinematic GNSS Data Processing

3.1. Kinematic Experimental Setup

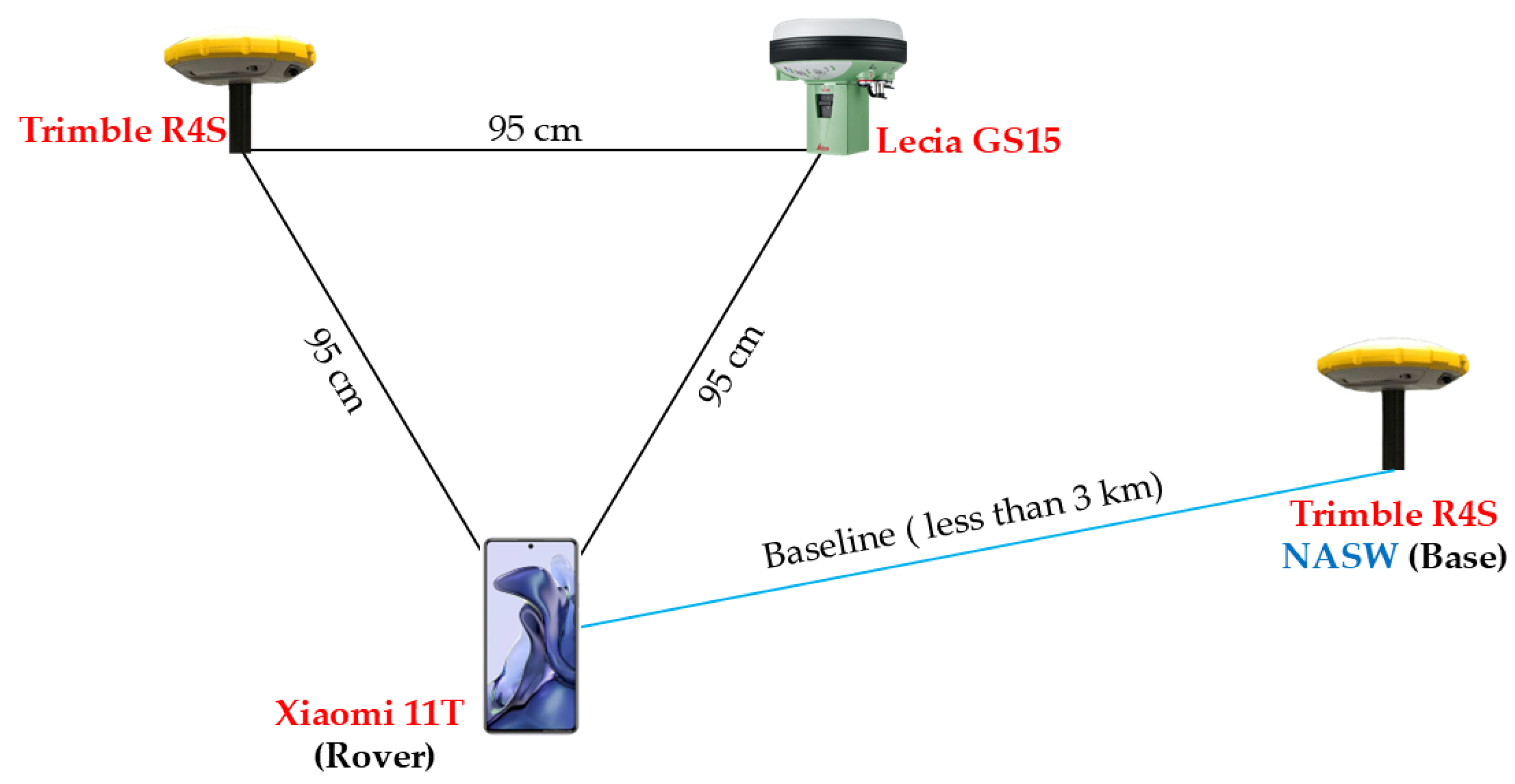

To examine the performance of the low-cost single-frequency multi-GNSS RTK and RP solutions for transport applications, a kinematic survey configuration was developed (

Figure 1). As given in

Figure 1, three GNSS receivers were mounted on a moving vehicle with a low-cost GNSS receiver (Xiaomi 11T, Beijing, China) and two geodetic-grade GNSS receivers (Leica GS15 (Heerbrugg, Switzerland) and Trimble R4S (Westminster, CO, USA)). In addition, a stationary geodetic GNSS receiver (Trimble R4S) was positioned over the New Aswan reference point to serve as a base station. Raw GNSS data were collected along a trajectory in New Aswan City, Egypt as depicted in

Figure 2.

The raw GNSS data collected from the two geodetic rover receivers were processed using carrier-phase RTK positioning with the RTKLIB GNSS software (version 2.4.3) serving as the ground truth for evaluating the smartphone-based positioning solutions [

30,

31]. The smartphone’s raw GNSS data were extracted directly in RINEX format using the Geo++RINEX Android application (version 2.1.6) [

20]. The characteristics of the smartphone GNSS data are summarized in

Table 1.

3.2. Kinematic GNSS Data Quality

As illustrated in

Figure 3, the number of satellites tracked for each GNSS constellation, and their corresponding horizontal dilution of precision (HDOP) values are presented. It is evident that the GPS and BDSs consistently maintain a higher number of tracked satellites (exceeding eight satellites per epoch), which results in favorable HDOP values that remain below 1.5 during all epochs; in contrast, the GLONASS system exhibits a comparatively lower number of tracked satellites, often not exceeding six and occasionally dropping to four satellites per epoch. This reduced satellite availability leads to significantly higher HDOP values, exceeding 3, indicating poorer horizontal positional accuracy.

The percentage of GNSS measurements is computed for each satellite system utilizing the RINEX SCAN (Version 1.0.0) software [

32]; then, it is summarized in

Table 2. It is clear that all GNSSs exhibit losses in phase measurements; however, the Galileo system experiences losses in both code and phase measurements for some satellites.

To further analyze the quality of GNSS data obtained from the smartphone, the carrier-to-noise density ratio (C/N0), which represents the received signal strength, was evaluated for each satellite [

33]. The minimum and maximum average C/N0 values for each GNSS constellation along with their corresponding satellite are illustrated in

Figure 4. It can be observed that all average C/N0 values fall within the range of 30 dB-Hz to 40 dB-Hz. In addition, the highest average C/N0 recorded was 39.002 dB-Hz by satellite C24, while the lowest was 30.596 dB-Hz, corresponding to satellite R01. Moreover,

Figure 4 also presents the epoch-by-epoch C/N0 variations throughout the trial, and it is shown that the signal strength fluctuates significantly over time with satellite G02 frequently reaching instantaneous C/N0 values as high as 45 dB-Hz.

3.3. Kinematic GNSS Data Processing Methodology

Based on the aforementioned data quality analysis, a variety of processing scenarios were implemented including the GPS-only (G), GPS/Galileo (GE), GPS/GLONASS (GR), GPS/BDS (GC), and all four systems (GREC) processing options. These configurations were expected to improve satellite availability and enhance its positioning geometry, as reflected by the HDOP. The number of visible satellites and their corresponding HDOP values for each processing scenario are given in

Figure 5.

Both RTK and relative positioning techniques were processed using the Net-Diff GNSS software (version 1.14) as summarized on

Table 3 [

34]. It is important to note that the Xiaomi 11T smartphone does not support navigation message recording. As a result, the broadcast navigation messages were obtained from the International GNSS Service (IGS) website [

35]; additionally, a stochastic model based on C/N0 and satellite elevation was applied. The mathematical expression of the stochastic model can be described as follows [

36]:

where

σ denotes signal uncertainty;

a and

b are factors that are derived from filter residuals;

E represents the satellite’s elevation angle; and C/N0 symbolizes the carrier-to-noise density ratio in dB-Hz (signal quality metric).

The processing outputs consisted of epoch-by-epoch latitude and longitude errors, referenced to the World Geodetic System 1984 (WGS-84). These geodetic coordinates were subsequently converted to projected coordinates in the Universal Transverse Mercator (UTM) Zone 36N, resulting in easting and northing values [

37]; thereafter, these were transformed into horizontal positioning errors using the following relation:

4. Results and Analysis

The horizontal positioning errors over time are shown in

Figure 6 for both RTK and RP solutions. It can be observed that the RTK processing scenarios achieve sub-1.5 m accuracy despite some fluctuations; moreover, the quad-constellation RTK solution demonstrates the best performance, consistently maintaining sub-1 m accuracy and even reaching below 50 cm at certain times.

On the other hand, the code-based RP approach exhibits meter-level performance with errors generally exceeding 3 m across all scenarios. Similarly to RTK, the quad-constellation RP solution shows the best results within its category, maintaining errors below 3 m for almost all epochs.

In general, it can be said that carrier-based RTK achieves horizontal positioning accuracy in the sub-meter to meter range, whereas code-only RP provides meter-level accuracy.

To further analyze the horizontal positioning accuracy, RMSE was evaluated using the following equation:

Table 4 summarizes the RMSE values for horizontal positioning accuracy using both RTK and RP methods. For RTK, all scenarios achieve sub-meter RMSE values with the GPS-only solution reaching 0.766 m in horizontal directions. The GREC solution demonstrates superior performance, achieving horizontal RMSE of 0.456 m; on the contrary, all RP scenarios exhibit meter-level horizontal RMSE values. The GPS-only solution records a horizontal RMSE of 1.703 m. Similarly to RTK, the multi-constellation solution, particularly (GREC) and (GE), offer superior performance, achieving horizontal RMSE values of 1.541 m.

Moreover, boxplots were used in order to better visualize and analyze the horizontal positioning accuracy of the proposed RTK and RP scenarios. The interquartile range (IQR) is calculated to show clear indication of consistency, while outliers highlight instances of degraded accuracy as given in

Figure 7. For the RTK solution, the IQR of the horizontal positioning errors are 0.575 m, 0.352 m, 0.492 m, 0.564 m, and 0.249 m for the G, GE, GR, GC, and GREC scenarios, respectively, whereas the RP’s values are 1.345 m, 1.196 m, 1.806 m, 1.343 m, and 1.017 m for the same scenarios, respectively. This shows that the RTK solutions exhibit more consistent horizontal positioning accuracy than the RP counterparts. Moreover, it is noticed that the horizontal positions discrepancies are narrowly distributed for RTK processing options particularly for GE and GREC options; on the other hand, these discrepancies are widely distributed for RP processing options.

5. Discussion

Real-time positioning is critical for transportation applications; consequently, high-precision positioning techniques such as RP or RTK are often preferred over low-cost alternatives like PPP, which is limited by its long convergence time. However, achieving cost-effective instantaneous positioning has become increasingly feasible due to advancements in GNSS technology. Therefore, in our research, we examine the positioning accuracy for both RTK and RP processing models for transportation applications.

For this purpose, the cumulative distribution function (CDF) of the horizontal positioning components is computed (

Figure 8). It is obvious that about 90% of the RTK- GREC horizontal errors are below 0.7 m, while it is less than 1.2 m for the RTK-GE solution; additionally, it under 1.4 m for the other RTK processing options. Regarding the RP processing solutions, the horizontal positioning errors are raised. For instance, 90% of the RP-GREC horizontal accuracy is below 2.5 m; however, it is approximately less than 3 m, 3.5 m, 3.5 m, and 5 m for GE, GC, G, and GR solutions.

Furthermore, the histogram of the horizontal positioning accuracy, along with the corresponding standard deviation (STD) that quantifies the precision of the error distribution along the trajectory, is computed and presented in

Figure 9 in order to enable a comparative assessment of the proposed processing scenarios. As shown, for the RTK solution, the horizontal error distributions range from 0 to 1 m, with a uniform distribution observed in the GE and GREC scenarios; moreover, the STD is significantly enhanced in case of the GREC scenario to reach 0.166 m compared to the other RTK scenarios. Adding Galileo observations to the RTK-GPS solution also improves the positioning’s precision compared to GLONASS and BDS as the STD of the RTK-GE solution is diminished to be 0.244 m in comparison to 0.364 m, 0.289, and 0.382 for the RTK-G, RTK-GR, and RTK-GC solutions, respectively.

For the RP solution, the 2D positioning errors range from 0 to 2 m with clear superiority to the GREC scenario. It is clear that the STD values are greater than their RTK counterparts. Additionally, the precision of the RP-GREC is the best among the other RP solutions as it decreased to be 0.704 m, while the STD metrics are 0.865 m, 0.786 m, 1.207 m, and 0.863 m for the RP-G, RP-GE, RP-GR, and RP-GC scenarios, correspondingly, with obvious superiority for the RP-GE scenario.

To better visualize the horizontal accuracy performance of the Xiaomi 11T using both RTK and RP methods, satellite imagery of road environments was utilized in QGIS (version 3.40.3) with Google Satellite imagery as the background [

38,

39]. The performance of the proposed RTK and RP solutions is presented in

Figure 10. Both positioning methods demonstrated high accuracy in suburban environments, with noticeable degradation in medium and challenging environments. The GREC scenario showed superior performance compared to the other RTK and RP solutions, especially in medium-complexity environments for both positioning modes.

6. Conclusions

In this study, the positioning accuracy of single-frequency quad-GNSS carrier-phase-based RTK and code-based RP was evaluated for transportation applications, utilizing the ultra-low-cost Xiaomi 11T smartphone.

Initially, the quality of the smartphone’s raw GNSS data was assessed by analyzing measurement availability. It was observed that all systems experienced carrier-phase measurement losses, while the Galileo system additionally suffered from code measurement losses. The signal strength, represented by C/N0, was also evaluated. Results indicated that the average C/N0 values did not exceed 40 dB-Hz and did not fall below 30 dB-Hz across all systems.

During the kinematic trial, the Xiaomi 11T achieved sub-meter-level accuracy using RTK and meter-level accuracy using RP. For the GPS-only configuration, the horizontal RMSE was 0.766 m for RTK and 1.703 m for RP. The quad-constellation solution demonstrated superior performance, achieving horizontal RMSE values of 0.456 m and 1.541 m for RTK and RP, respectively.

Overall, Xiaomi 11T has demonstrated its capability to support urban transportation applications that require real-time sub-meter-level positioning accuracy, such as autonomous vehicle navigation, lane-level positioning for advanced driver-assistance systems, public transport monitoring, and precise traffic monitoring.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A., H.A.K. and A.A.; methodology, M.A. and H.A.K.; software, H.A.K.; validation, M.A. and H.A.K.; formal analysis, A.A. and H.A.K.; investigation, M.A.; resources, A.A. and H.A.K.; data curation, H.A.K. and A.A.; writing—original draft preparation, H.A.K.; writing—review and editing, M.O.A.M.; visualization, M.A. and M.O.A.M.; supervision, M.A.; project administration, M.A.; funding acquisition, M.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project is sponsored by Prince Sattam Bin Abdulaziz University (PSAU) as part of funding for its SDG Roadmap Research Funding Program, project number PSAU-2023- SDG-43.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

This project is sponsored by Prince Sattam Bin Abdulaziz University (PSAU) as part of funding for its SDG Roadmap Research Funding Program, project number PSAU-2023- SDG-43.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Guo, Y.; Tian, Z.; Li, B.; Zhou, J.; Yin, Z.; Dong, Q.; Ying, S. Lane-Level Map Matching for Vehicles Using Mask-Based Raster High-Definition Maps. Expert. Syst. Appl. 2025, 287, 128195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nour, M.; Nour, M.; Zaki, M.H. Integrating Vehicle-to-Infrastructure Communication for Safer Lane Changes in Smart Work Zones. World Electr. Veh. J. 2025, 16, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Winkel, K.N.; Christoph, M. Rethinking Advanced Driver Assistance System Taxonomies: A Framework and Inventory of Real-World Safety Performance. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2025, 29, 101336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann-Wellenhof, B.; Lichtenegger, H.; Wasle, E. GNSS–Global Navigation Satellite Systems: GPS, GLONASS, Galileo, and More; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; ISBN 3211730176. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Dong, X.; Liu, G.; Gao, M.; Zhao, W.; Lv, D.; Cao, S. Low-Cost Single-Frequency DGNSS/DBA Combined Positioning Research and Performance Evaluation. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, D.; Yu, B.; Zhao, J.; Li, S.; Zhou, H.; Xu, Y. Augmenting Vehicle GNSS Positioning through Cross-Street Measurements in Urban Canyons. Measurement 2026, 257, 118603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.M.; Park, J.W.; Lee, J.S.; Han, S.K. Assessment of the GNSS-RTK for Application in Precision Forest Operations. Remote Sens. 2023, 16, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Fu, J.; Xu, S.; Han, T.; Liu, Y. Research on Integrated Navigation System of Agricultural Machinery Based on RTK-BDS/INS. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monjardín-Armenta, S.A.; Rangel-Peraza, J.G.; Sanhouse-García, A.J.; Plata-Rocha, W.; Rentería-Guevara, S.A.; Mora-Félix, Z.D. Statistical Comparison Analysis of Different Real-Time Kinematic Methods for the Development of Photogrammetric Products: CORS-RTK, CORS-RTK + PPK, RTK-DRTK2, and RTK + DRTK2 + GCP. Open Geosci. 2024, 16, 20220650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czyża, S.; Szuniewicz, K.; Kowalczyk, K.; Dumalski, A.; Ogrodniczak, M.; Zieleniewicz, Ł. Assessment of Accuracy in Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) Pose Estimation with the REAL-Time Kinematic (RTK) Method on the Example of DJI Matrice 300 RTK. Sensors 2023, 23, 2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segovia Ramírez, I.; Parra Chaparro, J.R.; García Márquez, F.P. Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Integrated Real Time Kinematic in Infrared Inspection of Photovoltaic Panels. Measurement 2022, 188, 110536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Zhang, Y.; Li, T.; Wang, C.; Wu, Q.; Pei, L.; Zhang, W.A. RTK-LIO: Tightly Coupled RTK/LiDAR/Inertial Navigation System Based on Optimization Approach. IEEE Sens. J. 2025, 25, 26220–26227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, S.; Zhou, S.; Song, W.; Li, R. Feature Augmented PPP-RTK/INS/Vision Integration Based on Combinatorial Optimization for Urban Vehicle Navigation. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2025, 36, 055101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yu, X.; Guo, S. Inversion and Characteristics of Unmodeled Errors in GNSS Relative Positioning. Measurement 2022, 195, 111151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korenberg, M.J.; Carvalho, G.S.; Silva, F.O.; Vinicius, M.; Pacheco, O.; Campos, G.A.O. Performance Analysis of Relative GPS Positioning for Low-Cost Receiver-Equipped Agricultural Rovers. Sensors 2023, 23, 8835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahfouz, A.; Menzio, D.; Dalla Vedova, F.; Voos, H.; Mahfouz, A.; Menzio, D.; Dalla Vedova, F.; Voos, H. GNSS-Based Baseline Vector Determination for Widely Separated Cooperative Satellites Using L1-Only Receivers. Adv. Space Res. 2024, 73, 5570–5581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Liu, Y.; Liu, F. An Improved Relative GNSS Tracking Method Utilizing Single Frequency Receivers. Sensors 2020, 20, 4073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, Y.; Wang, S.; Liu, C. Research on GNSS Multi-System Relative Positioning Algorithm. Commun. Comput. Inf. Sci. 2019, 980, 434–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innovation: Precise Positioning Using Raw GPS Measurements from Android Smartphones—GPS World. Available online: https://www.gpsworld.com/innovation-precise-positioning-using-raw-gps-measurements-from-android-smartphones/ (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Geo++ RINEX Logger—Apps on Google Play. Available online: https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=de.geopp.rinexlogger (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- GnssLogger App—Apps on Google Play. Available online: https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.google.android.apps.location.gps.gnsslogger (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Yong, C.; Odolinski, R.; Zaminpardaz, S.; Moore, M.; Rubinov, E.; Er, J.; Denham, M. Instantaneous, Dual-Frequency, Multi-GNSS Precise RTK Positioning Using Google Pixel 4 and Samsung Galaxy S20 Smartphones for Zero and Short Baselines. Sensors 2021, 21, 8318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Ding, H.; Zhang, L.; Chen, L.; Guo, W.; Lin, W.; Qi, S. Performance Verification of GNSS/5G Tightly Coupled Fusion Positioning in Urban Occluded Environments with a Smartphone. GPS Solut. 2025, 29, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaštík, J.; Hernández Olcina, J.; Saloň, Š.; Tunák, D. Pixel 5 Versus Pixel 9 Pro XL—Are Android Devices Evolving Towards Better GNSS Performance? Sensors 2025, 25, 4452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xia, M.; Zhang, D.; Wen, W.; Chen, W.; Shi, C. Urban GNSS Positioning for Consumer Electronics: 3D Mapping and Advanced Signal Processing. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2025, 71, 7059–7072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlovčič-Prešeren, P.; Dimc, F.; Bažec, M. Exploiting the Sensitivity of Dual-Frequency Smartphones and GNSS Geodetic Receivers for Jammer Localization. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Li, X.; Li, X.; Han, X.; Shen, Z. Enhancing Smartphone-Based Vehicle Navigation in Deep Urban Areas Using Machine Learning-Aided PPP-RTK. GPS Solut. 2025, 29, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, X.; Liu, W.; Wang, Y.; Li, L.; Zhu, F.; Zhang, X. Smartphone RTK Positioning with Multi-Frequency and Multi-Constellation Raw Observations: GPS L1/L5, Galileo E1/E5a, BDS B1I/B1C/B2a. J. Geod. 2023, 97, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghilani, C.D.; Wolf, P.R. Elementary Surveying; Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; ISBN 0132554348. [Google Scholar]

- Takasu, T.; Yasuda, A. Development of the Low-Cost RTK-GPS Receiver with an Open Source Program Package RTKLIB. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on GPS/GNSS, International Convention Center Jeju Korea, Seogwipo-si, Republic of Korea, 4–6 November 2009; Volume 1, pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Wiśniewski, B.; Bruniecki, K.; Moszyński, M. Evaluation of RTKLIB’s Positioning Accuracy Usingn Low-Cost GNSS Receiver and ASG-EUPOS. TransNav Int. J. Mar. Navig. Saf. Sea Transp. 2013, 7, 79–85. [Google Scholar]

- Ozdemir, B.N. RINEX SCAN: Open-Source RINEX Epoch and Frequency Scanning Software. Earth Sci. Inform. 2025, 18, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swamy, K.C.T.; Pasuluri, B.S.; Akash Venkata Ramana, G.; Jaya Tarun, K.; Bharath, M.; Dileep Kumar, B. Analysis of Carrier to Noise Density Ratio, Satellite Visibility and Skyplot of Multiple GNSS Constellations Using Smart Phone for Relative Positioning Application. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Emerging Smart Computing and Informatics, ESCI 2024, Pune, India, 5–7 March 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, J.; Gong, X.; Chen, Q. The Update of BDS-2 TGD and Its Impact on Positioning. Adv. Space Res. 2020, 65, 2645–2661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDDIS||Data and Derived Products|GNSS|GNSS Data and Product Archive. Available online: https://cddis.nasa.gov/Data_and_Derived_Products/GNSS/GNSS_data_and_product_archive.html (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Banville, S.; Lachapelle, G.; Ghoddousi-Fard, R.; Gratton, P. Automated Processing of Low-Cost GNSS Receiver Data. In Proceedings of the 32nd International Technical Meeting of the Satellite Division of the Institute of Navigation (ION GNSS+2019), Miami, FL, USA, 16–20 September 2019; pp. 3636–3652. [Google Scholar]

- Noureldin, A.; Karamat, T.B.; Georgy, J. Fundamentals of Inertial Navigation, Satellite-Based Positioning and Their Integration; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 1–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- QGIS Web Site. Spatial Without Compromise. Available online: https://qgis.org/ (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Google Earth. Available online: https://earth.google.com/web/@0,-0.31,0a,22251752.77375655d,35y,0h,0t,0r/data=CgRCAggBQgIIAEoNCPwEQAA (accessed on 29 August 2025).

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).