1. Introduction

Health professionals with diverse social identities, including disability, are needed for their valuable contributions to patient care and the healthcare system [

1,

2]. The inclusion of disabled health professionals begins with including students living with disabilities in health professional education programs (HPPs). The Accessible Canada Act and Articles 24 (right to education) and 27 (reasonable accommodation at the workplace) of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, legally require the removal of barriers to access for disabled people both domestically and globally [

3,

4]. These changes in legislation and greater awareness are leading to more disabled students accessing post-secondary education, including HPPs [

5,

6]. However, students living with disabilities experience delays in program progression/graduation, lower retention, and higher attrition [

7,

8]. They also report ongoing barriers within HPPs for several reasons, including stigma, discrimination and ableism [

9].

HPPs require students to complete university-based coursework and fieldwork. Fieldwork education provides students with opportunities to apply their classroom learning to real-world contexts. This learning typically occurs beyond the campus environment and may be referred to as experiential learning, clinical education, clerkship, professional placement or practicum. Supports, such as accommodations, provided by post-secondary education institutions are typically focused on university-based coursework, rather than the continuum of educational experiences, which include fieldwork [

10]. While some accommodations developed for university-based learning may apply to fieldwork, they are not always sufficient [

11,

12]. Examples of accommodations specific to the fieldwork setting include fieldwork sites close to the students’ homes, fieldwork deferrals, adaptive equipment (e.g., transparent surgical masks for lipreading) [

11,

12]. A recent scoping review of strategies to increase accessibility, including accommodation, in HPPs showed that these strategies are not routinely evaluated and thus, it is unknown to what extent they work [

11].

The challenges that disabled students identify in HPPs extend into fieldwork education due to its inflexibility, complexity and dynamic nature [

13]. A recent survey of students living with disabilities in HPPs indicates they struggle to navigate accommodation processes due to poor communication and a lack of clarity in complex systems [

14]. Disabled students are often dependent on fieldwork educators and coordinators to ensure their accommodation needs are met and report stigma and discrimination in this process.

University-based fieldwork coordinators search for supportive and collaborative educators when finding fieldwork opportunities for students because fieldwork educators provide direct supervision and assessment of student learning. A recent mixed-methods study explored the experiences of university-based fieldwork coordinators and found two major themes [

15]. First, coordinators were committed to student success, but constantly navigating challenges presented by post-secondary institutions, such as the limited knowledge that advisors in the student disability office, where accommodation plans are developed, had about fieldwork in HPPs [

15]. Secondly, coordinators work within evolving human dynamics and social norms such that students’ decisions regarding disclosure and the nature of fieldwork settings vary widely, requiring a nuanced approach to accommodation planning each time [

15].

The fieldwork educator can facilitate the successful engagement of students in their setting through the removal of barriers, so their perspective is important. This is critical when supervising disabled students given the additional barriers they experience [

13,

14]. For HPP faculty and staff to support fieldwork educators, understanding their experiences and perspectives is essential. While the experiences of university-based educators in supporting students with disabilities have been studied previously [

16], a focus on fieldwork educators, particularly across more than one health profession, is limited. The purpose of this study is to understand the experiences and perspectives of fieldwork educators when supervising students living with disabilities from HPPs in fieldwork. A secondary aim is to compare the perspectives of disabled versus nondisabled fieldwork educators for further insights. The findings from this study may inform the development of accommodation and accessibility supports and practices.

2. Materials and Methods

A cross-sectional survey of fieldwork educators was conducted to understand their perspectives on supervising disabled students. The study is part of a larger initiative within the School of Rehabilitation Science at McMaster University to explore strategies to improve the accessibility of HPPs for applicants/students living with disabilities [

11]. Ethics approval was provided by the Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board (ID# 17527).

2.1. Survey Design

The research team selected and adapted a subset of questions from prior surveys [

14,

15,

17] to suit the local context and ensure responses could be collected in approximately 35 min. Survey questions were selected if they aligned with the study’s purpose. An example of how the local context was considered was the renaming of the nature of disabilities to match categories used in disability work on campus.

The survey was structured with stemming questions, such that if respondents answered ‘yes’ to an initial question, a “stem”, they received follow-up questions seeking more information. For example, respondents were asked whether they received accommodation plans. Those who indicated that they did were asked further questions related to the accommodations provided. This design was chosen because respondents with practical knowledge would be best suited to explain their perspective on the phenomenon.

The preliminary survey was shared with an advisory committee that had been established to support the broader initiative. This committee included student consultants with lived experience, leadership from HPPs, and representatives from key service providers across campus. The committee provided feedback on the content and clarity of the survey and modifications were made based on their feedback. The revised survey was uploaded to LimeSurvey for electronic distribution.

In the final version of the survey, there were 35 questions. The following number and types of questions were included: 15 ‘select all’, 9 ‘select one’, 6 ‘free text’, 1 ‘select all and comment’, 1 ‘number’, 1 ‘rank choice’ and 1 Likert question. Fifteen of these questions were stem questions. The full survey is available in the

Supplementary File S1.

2.2. Participants and Recruitment

Fieldwork educators who supervise students from nine HPPs across the Faculty of Health Sciences at McMaster University were invited to complete the survey. The nine programs were occupational therapy (OT), physiotherapy (PT), speech-language pathology (SLP), child-life and pediatric psychosocial care (CL), psychotherapy, medicine (UGME), nursing (RN), physician-assistant (PA), and midwifery (MW). The university-based faculty members responsible for fieldwork in the HPPs distributed the survey to fieldwork educators by email. Educators were eligible to participate if they supervised HPP students in fieldwork.

One author (S.D.) followed up with the same faculty members to request a reminder email be sent to the program’s fieldwork educators two weeks after the initial survey distribution. The information letter/consent form was circulated as an attachment to the recruitment email. Consent was confirmed through the first survey question, which asked if the respondent had read and understood the information in the consent form, had their questions answered and agreed to take part in the study. A sample size calculation is not possible as the recruitment email was sent by faculty members and could have been forwarded to other colleagues.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize responses as counts and percentages, while content analysis was used for open-text responses [

18]. Percentages represent the proportion of eligible participants who responded to the respective survey questions. Respondents were considered eligible if they had the opportunity to answer a question. For example, all those who indicated they were living with a disability were eligible for questions characterizing their disability while those who indicated no disability were ineligible.

For questions in which we asked participants to rank the three most important items, we generated a summary score for each item by multiplying the number of respondents who rated an item as most important by three, the second-ranked item by two, and the third-ranked item by one. To obtain an overall score for each item, we divided the sum of these three products by the number of eligible respondents. All analyses were conducted using Microsoft Excel (2024).

3. Results

In total, 42 respondents provided consent in the survey to participate in the study. The majority were OTs (N = 13, 31%), practicing between 6–15 years (N = 23, 55%), in an outpatient hospital setting (N = 21, 50%), with adults (N = 24, 57%), their employer required them to supervise students in fieldwork (N = 27, 64%), and they reported receiving formal education in accessibility/accommodation (N = 26, 62%) (

Table 1).

Of the 26 respondents who reported receiving formal education, 20 (77%) stated the focus of the training was a proactive, barrier-removal accessibility approach, 14 (54%) stated the focus was an individualized accommodation approach and 2 (8%) were unsure. With respect to the education provider, 15 (58%) respondents indicated they received training from their workplace; 12 (46%) through their own professional development; 12 (46%) from their health professional education; and 5 (19%) from the student’s university. Most often, respondents requested more education on how to provide individualized support and accommodations to students with specific needs (N = 8, 31%).

Of the total 42 respondents, 10 (24%) identified as living with a disability, and the majority acquired their disabilities before practicing as health professionals (

Table 2). Most disabled respondents selected more than one category to describe the nature of their disabilities, and half of those respondents indicated they did not receive accommodations at work (N = 5, 50%). Of those who reported receiving workplace accommodations, the types of accommodations included support for physical tasks, assistive technology/computer or furniture modifications, alternative formats for documents, captioning and digital stethoscopes.

3.1. Supervising Disabled Students

Most survey respondents (N = 27, 64%) reported they had supervised a fieldwork student who was living with a disability within the previous 10 years; however, 6 (14%) had not and 9 (21%) were not sure if any of the students they had supervised were disabled. Of the respondents who had supervised a student living with a disability, 23 (85%) supervised five or fewer disabled students, 3 (11%) did not know how many students living with disabilities they supervised, and 1 (4%) supervised more than 10 disabled students. Almost half indicated they never received an accommodation plan from the program, and the nature of the students’ disabilities was most often mental health (N = 16, 59%), as reported by the respondents (

Table 3).

Of the 12 respondents who always or sometimes received students’ accommodation plans, 6 (50%) indicated they were consulted about these plans. However, when all 27 respondents who supervised students living with disabilities are included in the analysis, only 22% were consulted. The reason why only 12 respondents were eligible for the consultation question is because they reported receiving accommodation plans.

Of those same 12 respondents, 8 (67%) indicated they were informed of students’ needs for accommodation from the student, 7 (58%) from the program’s academic coordinator and 5 (42%) stated there was no routine method of notification. Most often (N = 8, 67%), accommodation plans were received before or at the beginning of the fieldwork experience. Respondents reported the types of accommodations most often implemented to support disabled students in fieldwork pertained to time (i.e., extra time, breaks/absences, altered schedules, etc.) and were evaluated through informal means (

Table 4).

3.2. Disabled Versus Nondisabled Respondents

To identify if there were any differences in the answers of respondents living with disabilities compared to those not living with disabilities, their answers were extracted separately and compared.

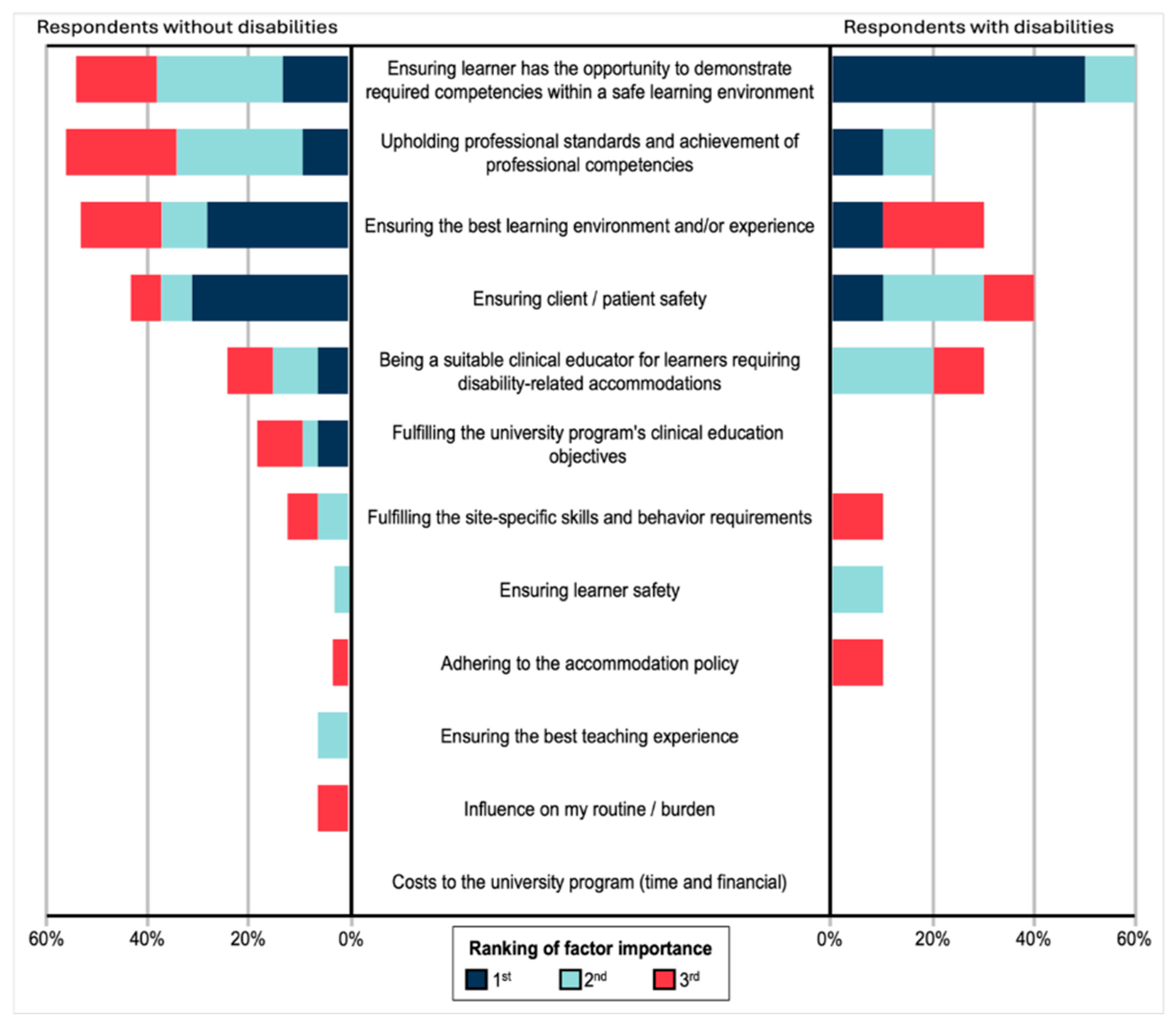

Figure 1 depicts the factors that respondents ranked as most important when implementing disability-related accommodations. Both disabled and nondisabled respondents ranked “ensuring client/patient safety” as the second most important factor (overall score = 0.80 and 1.13, respectively). However, respondents living with disabilities ranked “ensuring student has opportunity to demonstrate required competencies within a safe learning environment” highest (overall score = 1.70) and respondents not living with disabilities ranked “ensuring the best learning environment and/or experience” highest (overall score = 1.19). Thus, disabled respondents emphasized a barrier-free and safe environment for students in their work as fieldwork educators. Numerical differences could not be compared as no statistical test exists to compare ranked items.

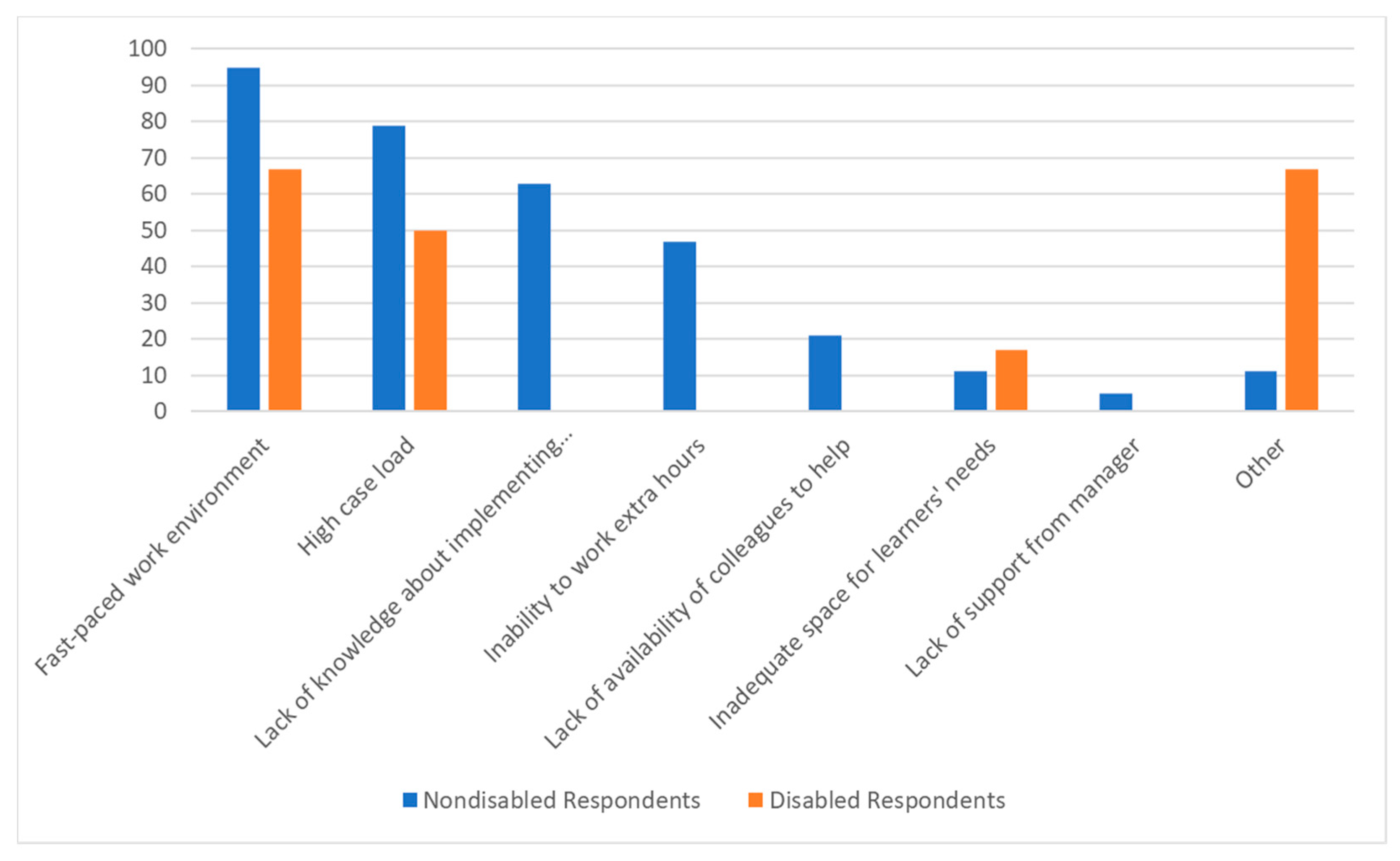

Figure 2 illustrates the challenges experienced by both respondents in their fieldwork education role by those living or not living with disabilities. Of the 27 eligible respondents, two did not provide a response. Of those remaining, both disabled respondents (N = 6) and nondisabled respondents (N= 19) reported a fast-paced work environment (N = 4, 67% & N = 18, 95%, respectively) and high case load (N = 3, 50% & N = 15, 79%, respectively) as their greatest challenges in this role. Notably, a lack of knowledge about implementing accommodations (N = 12, 63%) was the next greatest challenge for respondents not living with disabilities; however, this challenge was not identified by any respondents living with disabilities. Disabled respondents identified “other” challenges, including a lack of communication from the program, timing of disclosure by the student, poor specificity of requirements for accommodation and meeting their own productivity requirements.

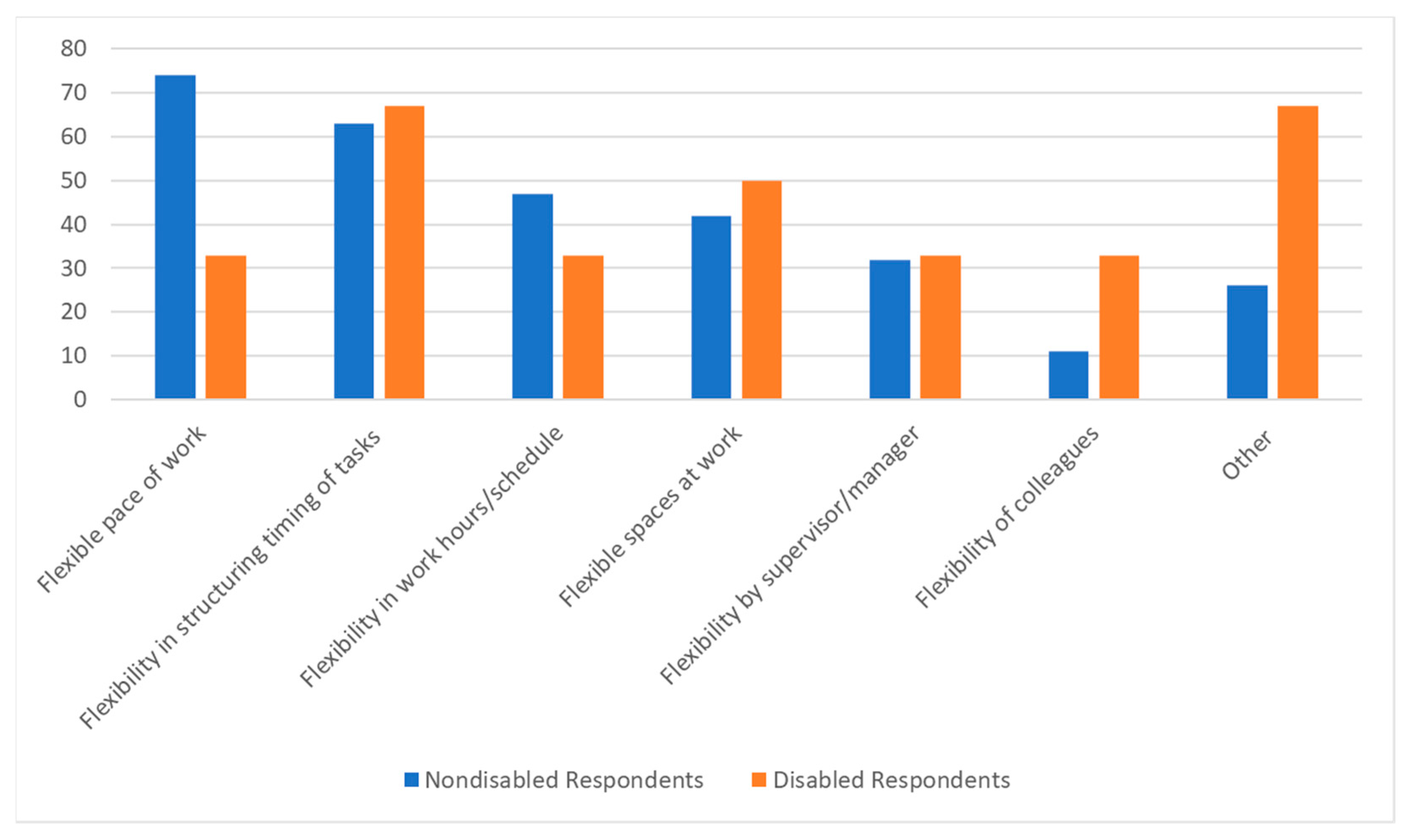

Figure 3 demonstrates the needs of disabled and nondisabled respondents in their fieldwork educator role. Respondents not living with disabilities indicated a flexible pace of work (N = 14, 74%) would be most helpful when supervising students with disabilities, whereas respondents living with disabilities indicated flexibility in the structuring/timing of work tasks (N = 4, 67%) would be most helpful. This factor was the second most helpful (N = 12, 63%) as reported by nondisabled respondents. Disabled respondents provided several “other” factors, such as being involved in the development of accommodations, having access to support if needed in accommodating students, greater transparency about accommodations and not having accommodation needs as a fieldwork educator.

There were some differences in the responses to the open-ended questions on the survey. Respondents’ experiences in fieldwork shaped future supervision of students living with disabilities such that both groups valued a learner-centred approach to working with each student to support their learning needs, regardless of whether a disability is present or identified. However, disabled respondents further elaborated on the steps they take to connect with students. These steps included: an explicit statement in their introductory letter expressing their commitment to support students living with disabilities; some disclosure of their own disabilities; and support needs to normalize the accommodation process. With respect to the implications of supervising disabled students for their practice, respondents living without disabilities mostly did not indicate any implications. Disabled respondents provided specific examples of strategies they used while supervising disabled students and how these are similar to strategies they use with clients, including asking about student/client preferences and ensuring accessible education materials.

Respondents were asked how HPPs and professional bodies could assist them in the supervision of students living with disabilities in fieldwork. Both disabled and nondisabled respondents agreed their highest need was strategies to reduce workplace barriers while supporting disabled students. Nondisabled respondents also provided specific suggestions related to information and resources they need in their role as fieldwork educator; this included: detailed accommodation plans, expectations for the learner, meetings with faculty, funding, staff and guides on how to balance accommodations and caseload management. In contrast, disabled respondents suggested external strategies that directly improve the experience of students, such as mentorship for students, repetitive normalization of accessibility and accommodation through standard use of an accessibility statement and features (e.g., closed captioning for videos) in all communications within professions. These differences demonstrate a focus on individualized support for respondents to support students versus system or structural level strategies to improve inclusion and acceptance of disability.

4. Discussion

In this cross-sectional study, fieldwork educators in nine HPPs were invited to complete a survey about their experiences and perceptions of supervising disabled students. Almost a quarter of the respondents identified living with a disability themselves. While many respondents reported having supervised at least one student living with a disability, almost half of them had never received an accommodation plan to support the student. The accommodations the fieldwork educators reported they most frequently implemented pertained to time, and evaluation of accommodations was often informal between student and fieldwork educator. Despite having formal education on accessibility and/or accommodations, some respondents expressed interest in learning about how to accommodate individual students with unique needs.

Strikingly, a minority of respondents sometimes or always received the students’ accommodation plans, and only half of them reported being involved in the accommodation planning process. This finding aligns with other research, which has recognized that fieldwork educators typically are not involved in accommodation development [

19]. Since students have several fieldwork opportunities across their HPPs, and their accommodation needs may vary from one setting to the next, the involvement of fieldwork educators is important to generate accommodations that are relevant and useful [

14]. However, the logistics of engaging fieldwork educators in this process are challenging because of the separate meetings that would be required of the fieldwork educators who supervise more than one student each year, and the meetings for the university-based fieldwork coordinator who oversees fieldwork assignments for all students in the HPP.

Student disability offices, where accommodations are developed, are often underresourced to meet the needs of students living with disabilities [

15]. One alternative to the current model is the development of a proactive accommodation plan, which is based on a student’s needs identified through a pre-placement meeting of the student, the fieldwork educator and the university-based fieldwork coordinator to apply the accommodations to the upcoming fieldwork setting [

20]. This approach will ensure the participation of the student, educator and coordinator and enable customization of the accommodation plan to the fieldwork site. However, this advanced planning will also increase time and scheduling demands for all.

Our survey results demonstrated a dominance of time-based accommodations, such as more time for tasks, time away from fieldwork, scheduling changes, etc. Time-based accommodations have been cited as a frequent and reasonable accommodation in other HPP studies [

12,

14]. As the priority, accommodations must reduce barriers to student learning. In this survey, responses provided in the “other” category of accommodations that fieldwork supervisors were asked to implement were uncommon but more complex and time-consuming to implement; these included selective patient assignment and hands-on skills support outside of the fieldwork setting. While complex accommodations may involve more resources, they are likely to set students up to succeed in fieldwork and their future practice.

Given the uniqueness of students, fieldwork settings and required tasks, evaluation is essential to determine accommodation effectiveness for enabling students to learn and demonstrate learning. However, findings from the survey indicated a lack of formal evaluation of accommodations. Respondents reported that evaluation typically happened informally by the student, the fieldwork educator or both. The experiences of both student and educator are valuable, but it’s possible that the effectiveness of the accommodation is conflated with the student’s performance in fieldwork. A lack of formal evaluation of accommodations is evident not only in fieldwork, but also in classroom settings and needs more attention [

14,

20]. The absence of evaluation may be due to the current constraints in the accommodation process, such as under-resourcing of student disability offices and the lack of tools for evaluation [

15].

Respondents also identified learning needs despite the majority reporting formal education in accessibility and accommodation legislation and practice. Specifically, they wanted to know how to best accommodate the specific student needs based on their conditions, age group, etc. This learning gap regarding the customization of accommodations is consistent with prior research [

19]. It is unrealistic for an educator to learn all possible accommodations their students may ever need, nor is this approach advisable since accommodations are meant to be individualized, not based on condition or age. Educators can learn to apply approaches and principles that facilitate successful implementation, such as collaborating with the student and program educator on the accommodation plan, as suggested earlier. This approach counters epistemic injustice in that the student’s knowledge of their needs and the strategies that work for them are recognized, believed and credible [

21]. If this approach is integrated and becomes usual practice, the accommodation development and implementation process will hopefully become easier.

Finally, the representation of fieldwork educators living with disabilities was almost 25% in this survey, whereas the prevalence of disabled health professionals varies considerably from 22% [

22] to 4.3% [

23], depending on the study. Disabled respondents are inclined to respond to an invitation to participate in research studies about disability-related issues [

24]. This may be because of their intimate knowledge of access as students, professionals and patients of the healthcare system themselves and therefore, the importance they place on rectifying the lack of inclusion in healthcare [

25,

26]. Across a variety of types of questions, including select all, ranking and open-text, the respondents living with disabilities in this study provided comments and suggestions from a justice lens and pertaining to systemic changes needed that might normalize disability, rather than “othering” disability. They emphasized the need to provide safe learning environments for disabled students to learn. Consistent with the existing literature, respondents not living with disabilities emphasized competency achievement and client safety in fieldwork education [

5]. Nondisabled respondents also identified their own support needs related to accommodating individual students; however, all professionals have the responsibility to normalize disability in the health professions. Perhaps engaging disabled professionals more explicitly will begin to model how to normalize the conversation around disability among health professionals.

Strengths and Limitations

The strength of this study is the breadth of health professional respondents who participated in the survey, some of whom are not well represented in this area of work, such as child life and pediatric psychosocial care. Also, the survey used in the study was modified from existing surveys implemented in previously published research [

14,

15,

17]. However, the sample size is small and limited to fieldwork educators affiliated with one university. Further, the survey questions were linked in that respondents were only eligible to answer certain questions based on previous responses. The “stem” nature of these questions decreased the number of responses even further for certain questions, which impacts the broad interpretation of the results. For example, only the 12 respondents who reported receiving accommodation plans were eligible for further questions about accommodations. However, fieldwork educators may be providing accommodations to students on-site without a formalized plan from the university; as such, the stem nature of the questions may have resulted in the exclusion of information that was relevant to the purpose of the study.