“We Carry the Burden of Doing Right, Doing Wrong, and the Guilt That Follows”: A Qualitative Study of Postpartum Experiences of Autistic and Non-Autistic Mothers

Abstract

1. Introduction

“Motherhood (and the right to exercise it) becomes a source of discrimination for women in general, and for disabled [or neurodivergent] women, it often entails serious and even harmful consequences”.[4] (p. 9)

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Materials

- (1)

- How did you experience the postpartum period during the first months at home? (general question)

- (1a)

- Did you feel that you had support during this stage? (specific question)

- (2)

- How was your postpartum care experience? (general question)

- (2a)

- Did healthcare professionals provide you with postpartum follow-up? (specific question)

- (3)

- How was your mood during the postpartum period? (general question)

- (3a)

- Did you experience any symptoms of depression during this stage? (specific question)

- (4)

- What type of feeding did you use for your baby? (general question)

- (4a)

- Did you use breastfeeding, formula feeding, or a combination of both? (specific question)

- (4b)

- How long did it last? (specific question)

- (4c)

- Did you face any challenges with breastfeeding/feeding? (specific question)

- (5)

- Would you like to add anything else about your postpartum experiences? (general)

- (5a)

- Do you have any advice or information for an autistic mother going through the postpartum period? (specific question)

2.3. Process

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Community Involvement

3. Results

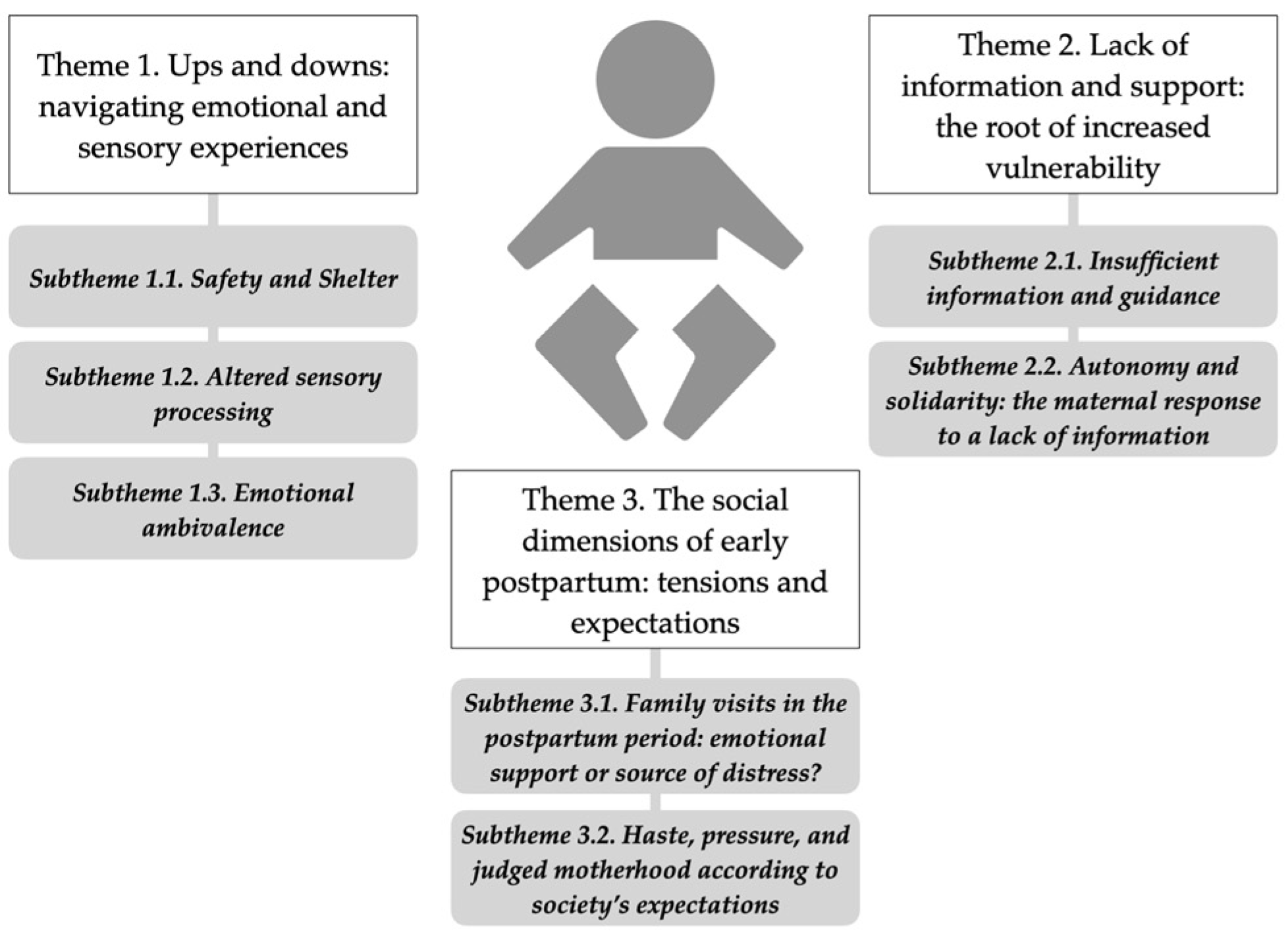

3.1. Theme 1: Ups and Downs: Navigating Emotional and Sensory Experiences

3.1.1. Subtheme: Safety and Shelter

“I saw myself as a total lioness; I didn’t want anyone to come near my child. I even remember lowering the blinds at home in case someone came by, thinking we weren’t there”.(autistic mother 1, has three children)

“I see myself as very mammalian, I think it was a bit like survival mode. I let that protective part toward my child emerge fully, even more than towards myself. I remember the first weeks feeling like something very animalistic, like I needed to stay at home. Going out made me feel insecure, not wanting to interact with other people. It wasn’t very rational—there were certain people who, if they came close to me, I felt a lot of rejection, not because I had anything against them”.(non-autistic mother 5, has one child)

3.1.2. Subtheme: Altered Sensory Processing

“I perceived breastfeeding as a moment of connection and tenderness, but most of the time nursing felt intrusive, and I had to make a great effort to endure without having a shutdown”.(autistic mother 4, has one child)

“I have been disconnected from my body, I don’t know if it was to recover quickly from the wounds and to be able to breastfeed despite being touched constantly”.(autistic mother 5, has one child)

“It is very invasive, yes, and as I said, they don’t explain anything either […] It felt more like pressure to continue with that breastfeeding […] I liked feeling that bond I hadn’t experienced, I wanted to live it, but I wasn’t comfortable”.(autistic mother 3, has three children)

“It wasn’t easy, but from 6 or 7 months, when the pain disappeared, it was super cool and still a very beautiful experience, with its ‘not so good’ things”.(non-autistic mother 5, has one child)

3.1.3. Subtheme: Emotional Ambivalence

“…a lot of sadness, a strong sense of loss, but at the same time also a lot of happiness and a strong feeling of rebirth, of rediscovering myself, my own body, and accepting my new reality”.(non-autistic mother 5, has one child)

3.2. Theme 2: Lack of Information and Support: The Root of Increased Vulnerability

3.2.1. Subtheme: Insufficient Information and Guidance

“Much of the information I gathered about motherhood wasn’t useful because it didn’t take into account the difficulties faced by an autistic person, especially someone hypersensitive like me. I had to figure out on the fly what worked and what didn’t, which is extremely hard for me and consumes a lot of energy and resources”.(autistic mother 4, has one child)

3.2.2. Subtheme: Autonomy and Solidarity: The Maternal Response to a Lack of Information

“I read a lot, I read a lot […] And I even took an online midwifery course, where they covered topics like breastfeeding, early care, and maternal rest”.(non-autistic mother 6, has one child)

“Find a mothers’ group. […] I’ve discovered that autistic women tend to want to help each other, share our experience and knowledge, support one another”.(autistic mother 4, has one child)

“I had to create my own birth guideline. Fortunately, my midwife and the entire maternity ward at the hospital were receptive and willing to adapt to my needs. […] We shouldn’t have to rely on luck to have our needs met”.(autistic mother 4, has one child)

3.3. Theme 3: The Social Dimensions of Early Postpartum: Tensions and Expectations

3.3.1. Subtheme: Family Visits in the Postpartum Period: Emotional Support or Source of Distress?

3.3.2. Subtheme: Haste, Pressure, and Judged Motherhood According to Society’s Expectations

“Simply being an autistic mother—just by being a mother, it feels like you lose your right to privacy, to have time for yourself, to meet your own needs, etc. For an autistic mother, this is terrible. How are we supposed to manage a situation or even a single day if we don’t have time to self-regulate? How can we handle social interaction if we don’t have time to prepare?”.(autistic mother 4, has one child)

“I thought people would respect my needs. But not being able to follow those standards turned into an endless source of problems […] I feel annoyed, frustrated, and anxious every time I have to deal with that kind of person”.(autistic mother 4, has one child)

“Everyone had an opinion—even if I didn’t ask for it. I decided to stop listening to most of it and go with my instincts. I felt much more confident”.(non-autistic mother 3, has three children)

“There’s a lot of pressure on mothers […] It’s like, ‘OK, you’re a mom, congratulations’, but two months later, everyone expects you to act as if you’re not”.(non-autistic mother 5, has one child)

“Most of the difficulties, the hardest and worst parts, came from outside […] society as a whole made my experience of motherhood infinitely more difficult and traumatic than it could have been”.(autistic mother 4, has one child)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Disability Language/Terminology Positionality Statement

References

- Ramos-Serrano, L.; Garcia-Molina, I. “I Am Their Haven”: Mothering Experiences of Spanish Autistic Mothers. Neurodiversity 2025, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargallo-Nieto, L.; Rodríguez-Zafra, A.; Clemente-Sánchez, M.; Garcia-Molina, I. Late diagnosis of autistic women in Spain: A participatory study. Women’s Stud. Int. Forum 2025, 113, 103177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Molina, I.; Cortés-Calvo, M. “Until I Had My Son, I Did Not Realise That These Characteristics Could Be Due to Autism”. Motherhood and Family Experiences of Spanish Autistic Mothers. Autism Adulthood 2024, 7, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomiz Pascual, M. del P. La Sexualidad y La Maternidad Como Factores Adicionales de Discriminación (y Violencia) En Las Mujeres Con Discapacidad. Rev. Esp. Discapac. 2016, 4, 123–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, D. Unlearning Shame: How Rejecting Self-Blame Culture Gives Us Real Power; Hachette UK: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Thom-Jones, S.; Brownlow, C.; Abel, S. Experiences of Autistic Parents, from Conception to Raising Adult Children: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Autism Adulthood 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagnier, M.; Moualla, M. The Autistic Parenting Journey: A Systematic Review of Qualitative Evidence and Thematic Meta-Synthesis. Autism Adulthood 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donovan, J.; Chiatti, B.D.; McKeever, A.; Bloch, J.R.; Gonzales, M.S.; Birati, Y. “Yes, I Can Bond.” Reflections of Autistic Women’s Mothering Experiences in the Early Postpartum Period. Women’s Health 2023, 19, 174550572311753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hampton, S.; Man, J.; Allison, C.; Aydin, E.; Baron-Cohen, S.; Holt, R. A Qualitative Exploration of Autistic Mothers’ Experiences II: Childbirth and Postnatal Experiences. Autism 2022, 26, 1165–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonnell, C.G.; DeLucia, E.A. Pregnancy and Parenthood Among Autistic Adults: Implications for Advancing Maternal Health and Parental Well-Being. Autism Adulthood 2021, 3, 100–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohl, A.L.; Crockford, S.K.; Blakemore, M.; Allison, C.; Baron-Cohen, S. A Comparative Study of Autistic and Non-Autistic Women’s Experience of Motherhood. Mol. Autism 2020, 11, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talcer, M.C.; Duffy, O.; Pedlow, K. A Qualitative Exploration into the Sensory Experiences of Autistic Mothers. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2023, 53, 834–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J.C.; Andrassy, B. Breastfeeding Experiences of Autistic Women. MCN Am. J. Matern./Child Nurs. 2022, 47, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Bas, G.A.; Youssef, G.J.; Macdonald, J.A.; Rossen, L.; Teague, S.J.; Kothe, E.J.; McIntosh, J.E.; Olsson, C.A.; Hutchinson, D.M. The Role of Antenatal and Postnatal Maternal Bonding in Infant Development: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Soc. Dev. 2020, 29, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segura González, R.M. El Efecto de los Factores Estresantes en las Mujeres. Altern. Psicol. Rev. Semest. 2015, 18, 35–47. [Google Scholar]

- Paricio del Castillo, R.; Polo Usaola, C. Maternidad e Identidad Materna: Deconstrucción Terapéutica de Narrativas. Rev. Asoc. Esp. Neuropsiquiatr. 2020, 40, 33–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, B.C.; Saldivia, S. Actualización En Depresión Postparto: El Desafío Permanente de Optimizar Su Detección y Abordaje. Rev. Med. Chile 2015, 143, 887–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buultjens, M.; Liamputtong, P. When Giving Life Starts to Take the Life out of You: Women’s Experiences of Depression after Childbirth. Midwifery 2007, 23, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J.L.; Warren, Z.E. Maternal Depressive Symptoms Following Autism Spectrum Diagnosis. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2012, 42, 1411–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrolini, V.; Rodríguez-Armendariz, E.; Vicente, A. Autistic Camouflaging across the Spectrum. New Ideas Psychol. 2023, 68, 100992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crane, L.; Lui, L.M.; Davies, J.; Pellicano, E. Autistic Parents’ Views and Experiences of Talking about Autism with Their Autistic Children. Autism 2021, 25, 1161–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dugdale, A.-S.; Thompson, A.R.; Leedham, A.; Beail, N.; Freeth, M. Intense Connection and Love: The Experiences of Autistic Mothers. Autism 2021, 25, 1973–1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marriott, E.; Stacey, J.; Hewitt, O.M.; Verkuijl, N.E. Parenting an Autistic Child: Experiences of Parents with Significant Autistic Traits. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2022, 52, 3182–3193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winnard, R.; Roy, M.; Butler-Coyne, H. Motherhood: Female Perspectives and Experiences of Being a Parent with ASC. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2022, 52, 2314–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Autistic Society. Autism: A Guide for Professionals. Available online: https://www.autism.org.uk/ (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Grant, A.; Jones, S.; Williams, K.; Leigh, J.; Brown, A. Autistic Women’s Views and Experiences of Infant Feeding: A Systematic Review of Qualitative Evidence. Autism 2022, 26, 1341–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demartini, B.; Nisticò, V.; Limonta, S.; Tarantino, V.; Stefanelli, G.; Calistro, F.; Giambanco, L.; Faggioli, R.; Gambini, O.; Turriziani, P. Long-Term Memory of Sensory Experiences from the First Pregnancy, Its Peri-Partum and Post-Partum in Women with Autism Spectrum Disorders without Intellectual Disabilities: A Retrospective Study. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2024, 54, 4709–4718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardner, M.; Suplee, P.D.; Bloch, J.; Lecks, K. Exploratory Study of Childbearing Experiences of Women with Asperger Syndrome. Nurs. Women’s Health 2016, 20, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, L. From Here to Maternity: Pregnancy and Motherhood on the Autism Spectrum; Jessica Kingsley Publishers: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolaidis, C.; Raymaker, D.; Kapp, S.K.; Baggs, A.; Ashkenazy, E.; McDonald, K.; Weiner, M.; Maslak, J.; Hunter, M.; Joyce, A. The AASPIRE Practice-Based Guidelines for the Inclusion of Autistic Adults in Research as Co-Researchers and Study Participants. Autism 2019, 23, 2007–2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, M. The Politics of Disablement—New Social Movements. In The Politics of Disablement; Macmillan Education UK: London, UK, 1990; pp. 112–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Reflecting on Reflexive Thematic Analysis. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2019, 11, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. To Saturate or Not to Saturate? Questioning Data Saturation as a Useful Concept for Thematic Analysis and Sample-Size Rationales. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2021, 13, 201–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, B.C.; Harris, I.B.; Beckman, T.J.; Reed, D.A.; Cook, D.A. Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research. Acad. Med. 2014, 89, 1245–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horton, E.; Brownhill, L.A.; Tones, D.; Goldschmied, A.Z.; Max, K.; Emine, G.; Dommett, E.; Lauren, W.; Taylor, J.; Carla, T.; et al. Developing an Evaluation Framework to Promote Meaningful Participation of Autistic People in Research: The ELPART and Participatory Group Checklist. Preprints 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, C.E.; Baron-Cohen, S. Sensory Perception in Autism. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2017, 18, 671–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leekam, S.R.; Nieto, C.; Libby, S.J.; Wing, L.; Gould, J. Describing the Sensory Abnormalities of Children and Adults with Autism. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2007, 37, 894–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampton, S.; Man, J.; Allison, C.; Aydin, E.; Baron-Cohen, S.; Holt, R. A Qualitative Exploration of Autistic Mothers’ Experiences I: Pregnancy Experiences. Autism 2023, 27, 1271–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, C.; Lepherd, L.; Ganguly, R.; Jacob-Rogers, S. Perinatal Issues for Women with High Functioning Autism Spectrum Disorder. Women Birth 2017, 30, e89–e95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, M.; McCowan, S.; Shaw, S.C. Autistic SPACE: A Novel Framework for Meeting the Needs of Autistic People in Healthcare Settings. Br. J. Hosp. Med. 2023, 84, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, L.; Kirton, J.; West, H.; Jackson, L.; Herron, K.; Cherry, M.G. The Interpersonal Experiences of Autistic Women and Birthing People in the Perinatal Period: A Systematic Review Using the Autistic SPACE Framework. J. Reprod. Infant. Psychol. 2025, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Molina, I. “When I Need Help, I Ask My Friends”: Experiences of Spanish Autistic Women When Disclosing Their Late Diagnosis to Family and Friends. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1342352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bargiela, S.; Steward, R.; Mandy, W. The Experiences of Late-Diagnosed Women with Autism Spectrum Conditions: An Investigation of the Female Autism Phenotype. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2016, 46, 3281–3294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leedham, A.; Thompson, A.R.; Smith, R.; Freeth, M. ‘I Was Exhausted Trying to Figure It out’: The Experiences of Females Receiving an Autism Diagnosis in Middle to Late Adulthood. Autism 2020, 24, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molina-Abarca, J.G. Maternidad y Autismo. In Mujeres y Autismo. La Identidad Camuflada; Merino, M., Ed.; 2022; pp. 283–292. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Molina, I. Revelar El Diagnóstico Para Construir Una Sociedad Más Tolerante: Relatos de Madres Autistas. In Proceedings of the 21st AETAPI Congress, Cádiz, Spain, 14–16 November 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny, L.; Hattersley, C.; Molins, B.; Buckley, C.; Povey, C.; Pellicano, E. Which Terms Should Be Used to Describe Autism? Perspectives from the UK Autism Community. Autism 2016, 20, 442–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacKinnon, K.R.; Lefkowitz, A.; Lorello, G.R.; Schrewe, B.; Soklaridis, S.; Kuper, A. Recognizing and Renaming in Obstetrics: How Do We Take Better Care with Language? Obstet. Med. 2021, 14, 201–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Autistic Mothers | Non-Autistic Mothers | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Age (Diagnosis Age) | N. Children (Age Range) | Mode of Birth | Group | Age | N. Children (Age Range) | Mode of Birth |

| Autistic mother 1 | 41 (40) | 3 (8–17) | Vaginal and cesarian | Non-autistic mother 1 | 39 | 3 (6–17) | Vaginal and cesarian |

| Autistic mother 2 | 36 (34) | 1 (4) | Vaginal | Non-autistic mother 2 | 35 | 1 (3) | Vaginal |

| Autistic mother 3 | 35 (34) | 3 (5–17) | Vaginal | Non-autistic mother 3 | 44 | 3 (6–19) | Vaginal |

| Autistic mother 4 | 40 (30) * | 1 (4) | Vaginal | Non-autistic mother 4 | 43 | 1 (3) | Vaginal |

| Autistic mother 5 | 35 (35) | 1 (2) | Cesarean | Non-autistic mother 5 | 30 | 1 (2) | Cesarean |

| Autistic mother 6 | 41 (40) | 1 (2) | Vaginal | Non-autistic mother 6 | 41 | 1 (2) | Vaginal |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

García-Plata, M.; Garcia-Molina, I. “We Carry the Burden of Doing Right, Doing Wrong, and the Guilt That Follows”: A Qualitative Study of Postpartum Experiences of Autistic and Non-Autistic Mothers. Disabilities 2025, 5, 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities5040086

García-Plata M, Garcia-Molina I. “We Carry the Burden of Doing Right, Doing Wrong, and the Guilt That Follows”: A Qualitative Study of Postpartum Experiences of Autistic and Non-Autistic Mothers. Disabilities. 2025; 5(4):86. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities5040086

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarcía-Plata, Marta, and Irene Garcia-Molina. 2025. "“We Carry the Burden of Doing Right, Doing Wrong, and the Guilt That Follows”: A Qualitative Study of Postpartum Experiences of Autistic and Non-Autistic Mothers" Disabilities 5, no. 4: 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities5040086

APA StyleGarcía-Plata, M., & Garcia-Molina, I. (2025). “We Carry the Burden of Doing Right, Doing Wrong, and the Guilt That Follows”: A Qualitative Study of Postpartum Experiences of Autistic and Non-Autistic Mothers. Disabilities, 5(4), 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities5040086