Social Dynamics Management in Inclusive Secondary Classrooms: A Qualitative Study on Teachers’ Practices to Promote the Participation of Students with Intellectual Disabilities

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Conceptualizing Social Participation

1.2. Explanatory Models

1.3. Social Dynamics Management

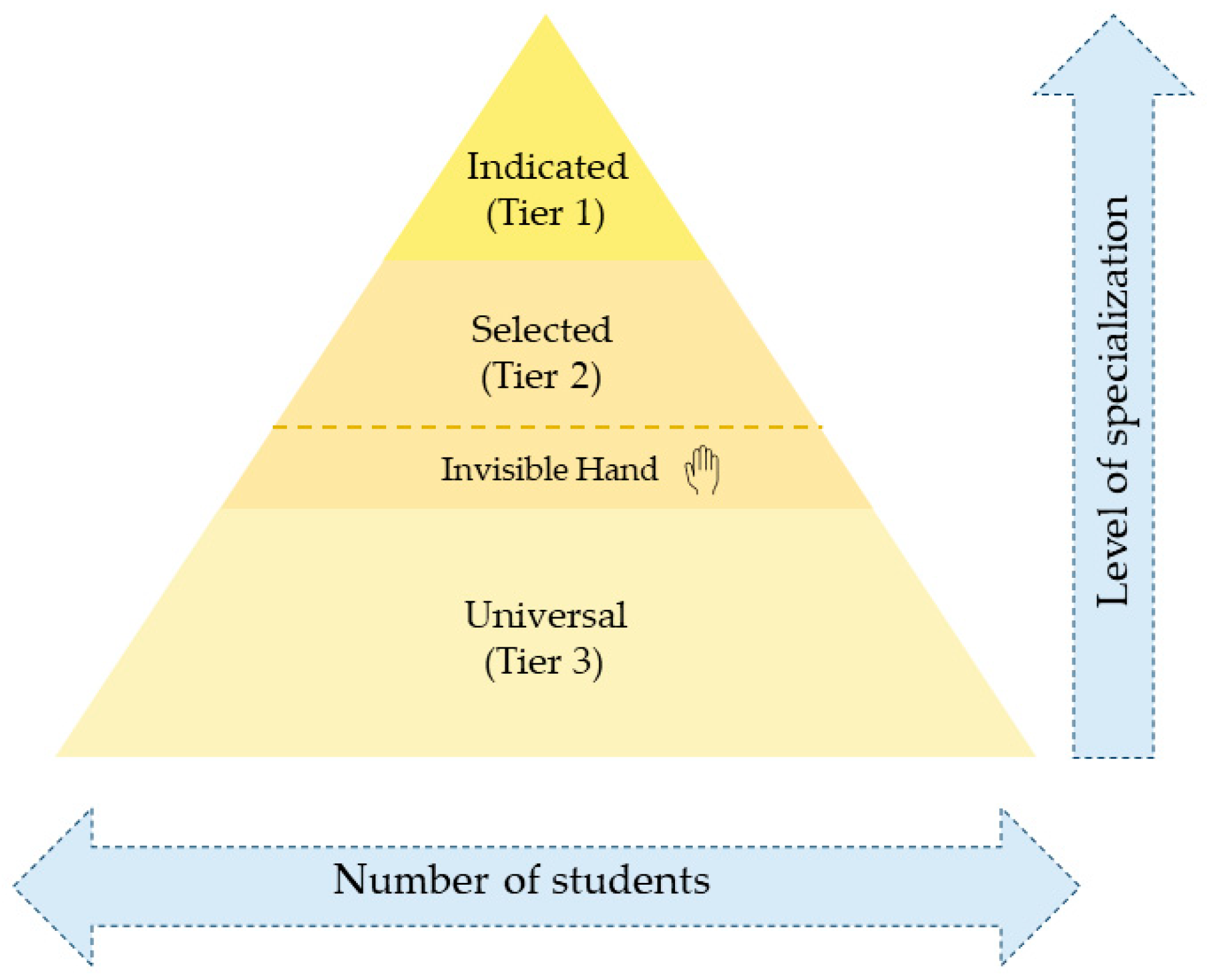

- Universal tier (Tier 1): Strategies for the entire class to promote positive participation conditions (e.g., classroom culture, group formation, inclusive values).

- Selected tier (Tier 2): Targeted support for the 10–15% of students who are at risk of exclusion, such as interventions that reduce social risk and build resilience. Teachers’ subtle orchestration of social dynamics is essential here, referred to as the invisible hand.

1.4. Research Gap

- What strategies do teachers report using across the three SDM tiers (universal, selected, indicated)?

- Are there additional practices beyond those described in the SDM model that teachers consider pedagogically relevant?

- How evenly is teachers’ professional knowledge distributed across the three tiers? Where do gaps appear?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample

2.2. Research Design and Research Procedure

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

“But what I actually want to say is that, for me, it’s not just the fit pupils who should be offered this opportunity, but it’s our job to see how we can simplify a topic so that everyone can benefit from it, so that everyone can learn the same subject matter.”(Interview 28, lines 120ff.)

“As I said, there is no catalogue for this either. It’s more of an intuitive behaviour, like, okay, what is wanted right now or what are the needs on the part of the children or on my part.”(Interview 23, lines 498ff.)

“We keep an eye on all the pupils, but diagnostics, and perhaps this has something to do with the fact that it is a ninth grade class, is not an issue for me.”(Interview 26, lines 684 ff.)

3.1. Teachers’ Knowledge in Promoting Social Participation

“I would say that through the way we live together in class, we have managed to establish a fairly eye-level structure. […] But I would say that we have quite little hierarchical structure in this class, as I know it from other classes.”(Interview 13, lines 973ff.)

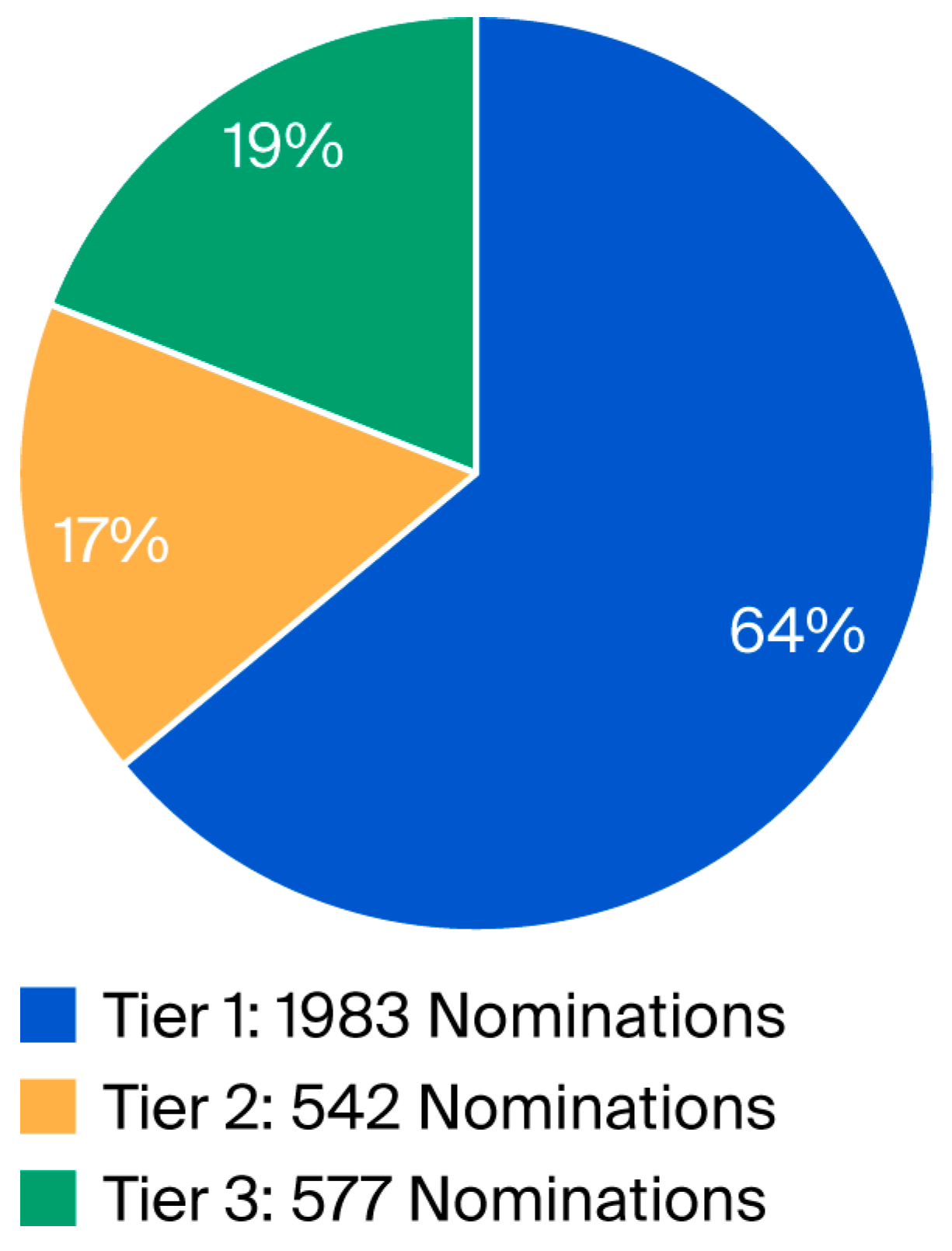

3.2. Importance of the Measures—Ranking of Mentions

“When you work as a team, things just go better and they establish themselves much more easily. And when I know I have a team, I don’t have to keep an eye on everything myself. […] Or everyone has a different perspective on certain problems, and that helps you to talk about them as a team and find solutions together.”(Interview 13, lines 459ff.)

“I think that’s such an invisible thing. That you look […] who would be a good fit for whom? Who could possibly work with whom?”(Interview 6, line 480ff.)

“But I would say that we have very little hierarchical structure in this class compared to what I have experienced in other classes. And working together benefits from either having a structure based on equality or having positive role models as discussion leaders or something like that”(Interview 13, line 973ff.).

“As I said, there is no catalogue there either. It’s more of an intuitive behavior, this okay, what is wanted or what are the needs on the part of the children or on my part.”(Interview 23, lines 498ff.)

“I believe that as a teacher you have more power than you sometimes think yourself. Through the attitude. It’s more of a feeling thing. So it’s not something specific that you do, but rather the feeling of sitting in the middle of these children.”(Interview 6, lines 792ff.)

4. Discussion

4.1. Broad but Unequal Knowledge Across SDM Tiers

4.2. Expansion of the SDM Model

4.3. Practical Implications

- Tier 2 interventions: The lack of clarity and visibility in this area suggests that teachers would benefit from training to help them recognize early signs of social exclusion and apply targeted, subtle interventions.

- Tier 3 approaches: Teachers need access to evidence-based tools and guidance for complex cases. Their frequent reliance on intuitive experimentation indicates that they are often left to act alone in high-stakes situations.

- General approaches: Given the importance of teachers’ attitudes, professional development should include opportunities for critical reflection on clear beliefs and values.

- Cross-professional cooperation: Schools should institutionalize cooperative structures and ensure that teachers are not isolated in their efforts to promote participation.

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Disability Language/Terminology Positionality Statement

Abbreviations

| SDM | Social Dynamics Management |

| ID | Intellectual Disabilities |

| MTSS | Multi-Tiered Systems of Support |

References

- Dell’Anna, S.; Pellegrini, M.; Ianes, D.; Vivanet, G. Learning, social, and psychological outcomes of students with moderate, severe, and complex disabilities in inclusive education: A systematic review. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 2022, 69, 2025–2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocaj, A.; Kuhl, P.; Kroth, A.J.; Pant, H.A.; Stanat, P. Wo lernen Kinder mit sonderpädagogischem Förderbedarf besser? Ein Vergleich schulischer Kompetenzen zwischen Regel- und Förderschulen in der Primarstufe. Kölner Z. Soziologie Sozialpsychologie 2014, 66, 165–191. [Google Scholar]

- Schuck, K.D.; Rauer, W.; Prinz, D. EiBiSch–Evaluation Inklusiver Bildung in Hamburgs Schulen: Quantitative und Qualitative Ergebnisse; Waxmann: Münster, Germany; New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bossaert, G.; de Boer, A.; Frostad, P.; Pijl, S.J.; Petry, K. Social participation of students with special educational needs in different educational systems. Irish Educ. Stud. 2015, 34, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koller, D.; Le Pouesard, M.; Rummens, J.A. Defining social inclusion for children with disabilities: A critical literature review. Child. Soc. 2018, 32, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krull, J.; Wilbert, J.; Hennemann, T. Does social exclusion by classmates lead to behaviour problems and learning difficulties or vice versa? A cross-lagged panel analysis. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2018, 33, 235–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cillessen, A.H.; Rose, A.J. Understanding popularity in the peer system. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2005, 14, 102–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karremans, J.C.; Finkenauer, C. Attraction and close relationships. In Social Psychology, 1st ed.; Hewstone, M., Stroebe, W., Jonas, K., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 347–378. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, R.G.; Taylor, E.M. Friendship and happiness in the third age. In Friendship and Happiness: Across the Life-Span and Cultures, 1st ed.; Demir, M., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 155–169. [Google Scholar]

- Sherman, A.M.; de Vries, B.; Lansford, J.E. Friendship in childhood and adulthood: Lessons across the life span. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 2000, 51, 31–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, J.A.; Inderbitzen, H.M. Peer acceptance and friendship: An investigation of their relation to self-esteem. J. Early Adolesc. 1995, 15, 476–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtzman, S.; DeClerck, D.; Turcotte, K.; Lisi, D.; Woodworth, M. Emotional support during times of stress: Can text messaging compete with in-person interactions? Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 71, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.M.; Vaterlaus, J.M.; Jackson, M.A.; Morrill, T.B. Friendship characteristics, psychosocial development, and adolescent identity formation. Pers. Relatsh. 2014, 21, 51–67. [Google Scholar]

- Powdthavee, N. Putting a price tag on friends, relatives, and neighbours: Using surveys of life satisfaction to value social relationships. J. Socio-Econ. 2008, 37, 1459–1480. [Google Scholar]

- Mund, M.; Johnson, M.D. Lonely me, lonely you: Loneliness and the longitudinal course of relationship satisfaction. J. Happiness Stud. 2021, 22, 575–597. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz-Mette, R.A.; Shankman, J.; Dueweke, A.R.; Borowski, S.; Rose, A.J. Relations of friendship experiences with depressive symptoms and loneliness in childhood and adolescence: A meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 2020, 146, 664–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koster, M.; Timmerman, M.E.; Nakken, H.; Pijl, S.J.; van Houten, E.J. Evaluating social participation of pupils with special needs in regular primary schools: Examination of a teacher questionnaire. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2009, 25, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulawiak, P.R.; Wilbert, J. Methoden zur Analyse der sozialen Integration von Schulkindern mit sonderpädagogischem Förderbedarf im gemeinsamen Unterricht. Empir. Sonderpädagogik 2015, 7, 241–257. [Google Scholar]

- Scharenberg, K.; Röhl, S. Klassenkomposition und soziale Integration in inklusiven Schulklassen. In Leistung und Wohlbefinden in der Schule: Herausforderung Inklusion; Rathmann, K., Hurrelmann, K., Eds.; Beltz: Weinheim, Germany, 2018; pp. 300–316. [Google Scholar]

- Zurbriggen, C.L.; Hofmann, V.; Lehofer, M.; Schwab, S. Social classroom climate and personalised instruction as predictors of students’ social participation. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2023, 27, 1223–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, R.; Carter, E.W.; Asmus, J.; Brock, M.E. Presence, proximity, and peer interactions of adolescents with severe disabilities in general education classrooms. Except. Child. 2016, 82, 192–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrote, A.; Dessemontet, R.S.; Opitz, E.M. Facilitating the social participation of pupils with special educational needs in mainstream schools: A review of school-based interventions. Educ. Res. Rev. 2017, 20, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köb, S.; Janz, F. Die soziale Position von Jugendlichen mit und ohne kognitive Beeinträchtigung in inklusiven Schulklassen–subjektive Theorien von Lehrkräften und Begründungen von Peers. Vierteljahresschr. Heilpädagogik Nachbargeb. 2020, 89, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Nowicki, E.A.; Brown, J.; Dare, L. Educators’ evaluation of children’s ideas on the social exclusion of classmates with intellectual and learning disabilities. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2018, 31, 154–163. [Google Scholar]

- Tobia, V.; Riva, P.; Caprin, C. Who are the children most vulnerable to social exclusion? The moderating role of self-esteem, popularity, and nonverbal intelligence on cognitive performance following social exclusion. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2017, 45, 789–801. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bossaert, G.; Colpin, H.; Pijl, S.J.; Petry, K. Truly included? A literature study focusing on the social dimension of inclusion in education. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2013, 17, 60–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asher, S.R.; Renshaw, P.D.; Hymel, S. Peer relations and the development of social skills. Young Child Rev. Res. 1982, 3, 137–158. [Google Scholar]

- Dijkstra, J.K.; Gest, S.D. Peer norm salience for academic achievement, prosocial behavior, and bullying: Implications for adolescent school experiences. J. Early Adolesc. 2015, 35, 79–96. [Google Scholar]

- Avramidis, E. Social relationships of pupils with special educational needs in the mainstream primary class: Peer group membership and peer-assessed social behaviour. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2010, 25, 413–429. [Google Scholar]

- Bukowski, W.M.; Hoza, B. Popularity and friendship: Issues in theory, measurement, and outcome. In Peer Relationships in Child Development, 1st ed.; Berndt, T.J., Ladd, G.W., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1989; pp. 15–45. [Google Scholar]

- Schwab, S. Social dimensions of inclusion in education of 4th and 7th grade pupils in inclusive and regular classes: Outcomes from Austria. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2015, 43, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hymel, S.; Wagner, E.; Butler, L.J. Reputational bias: View from the peer group. In Peer Rejection in Childhood, 1st ed.; Kupersmidt, J.B., Dodge, K.A., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990; pp. 156–186. [Google Scholar]

- Mamas, C.; Schaelli, G.H.; Daly, A.J.; Navarro, H.R.; Trisokka, L. Employing social network analysis to examine the social participation of students identified as having special educational needs and disabilities. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 2020, 67, 393–408. [Google Scholar]

- Woolfson, L.M. Is inclusive education for children with special educational needs and disabilities an impossible dream? Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2025, 95, 725–737. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design, 1st ed.; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Sameroff, A. Dynamic developmental systems: Chaos and order. In Chaos and Its Influence on Children’s Development: An Ecological Perspective, 1st ed.; Evans, G.W., Wachs, T.D., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2010; pp. 255–264. [Google Scholar]

- Rapp, A.C.; Corral-Granados, A. Understanding inclusive education—A theoretical contribution from system theory and the constructionist perspective. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2021, 28, 423–439. [Google Scholar]

- Maciver, D.; Rutherford, M.; Arakelyan, S.; Kramer, J.M.; Richmond, J.; Todorova, L.; Forsyth, K. Participation of children with disabilities in school: A realist systematic review of psychosocial and environmental factors. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0210511. [Google Scholar]

- Darwish, S.; Alodat, A.; Al-Hendawi, M.; Ianniello, A. General Education Teachers’ Perspectives on Challenges to the Inclusion of Students with Intellectual Disabilities in Qatar. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmer, T.W.; Dawes, M.; Hamm, J.V.; Lee, D.; Mehtaji, M.; Hoffman, A.S.; Brooks, D.S. Classroom social dynamics management: Why the invisible hand of the teacher matters for special education. Remedial Spec. Educ. 2018, 39, 177–192. [Google Scholar]

- Farmer, T.W.; Hamm, J.V.; Dawes, M.; Barko-Alva, K.; Cross, J.R. Promoting inclusive communities in diverse classrooms: Teacher attunement and social dynamics management. Educ. Psychol. 2019, 54, 286–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gest, S.D.; Madill, R.A.; Zadzora, K.M.; Miller, A.M.; Rodkin, P.C. Teacher management of elementary classroom social dynamics: Associations with changes in student adjustment. J. Emot. Behav. Disord. 2014, 22, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juvonen, J.; Lessard, L.M.; Rastogi, R.; Schacter, H.L.; Smith, D.S. Promoting social inclusion in educational settings: Challenges and opportunities. Educ. Psychol. 2019, 54, 250–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. Ecological systems theory. Ann. Child Dev. 1989, 6, 187–249. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, L.B.; Thelen, E. Development as a dynamic system. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2003, 7, 343–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meuser, S.; Piskur, B.; Hennissen, P.; Dolmans, D. Targeting the school environment to enable participation: A scoping review. Scand. J. Occup. Ther. 2023, 30, 298–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamm, J.V.; Farmer, T.W.; Dadisman, K.; Gravelle, M.; Murray, A.R. Teachers’ attunement to students’ peer group affiliations as a source of improved student experiences of the school social–affective context following the middle school transition. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2011, 32, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norwalk, K.E.; Hamm, J.V.; Farmer, T.W.; Barnes, K.L. Improving the school context of early adolescence through teacher attunement to victimization: Effects on school belonging. J. Early Adolesc. 2016, 36, 989–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, S.S.; Zadzora, K.M.; Miller, A.M.; Gest, S.D. Predicting elementary teachers’ efforts to manage social dynamics from classroom composition, teacher characteristics, and the early year peer ecology. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2019, 22, 795–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Berg, Y.H.M.; Stoltz, S.E.M.J. Enhancing social inclusion of children with externalizing problems through classroom seating arrangements: A randomized controlled trial. J. Emot. Behav. Disord. 2018, 26, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odescalchi, C.; Gasteiger-Klicpera, B. Looking behind the desks: Secondary school teachers’ perceptions and strategies regarding the social participation of students with SEBD. Emot. Behav. Diffic. 2025, 30, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- de Leeuw, R.R.; de Boer, A.A.; Bijstra, J.; Minnaert, A.E. Teacher strategies to support the social participation of students with SEBD in the regular classroom. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2018, 33, 412–426. [Google Scholar]

- Odescalchi, C.; Paleczek, L.; Gasteiger-Klicpera, B. Primary school teachers’ social-emotional competencies and strategies in fostering the social participation of students with SEBD. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2025, 40, 393–407. [Google Scholar]

- Batsche, G. Multi-Tiered System of Supports for Inclusive Schools. In Handbook of Effective Inclusive Schools, 1st ed.; McLeskey, J., Waldron, N.L., Spooner, F., Algozzine, B., Eds.; Taylor & Francis: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 183–196. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, D. What Really Works in Special and Inclusive Education: Using Evidence-Based Teaching Strategies, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lane, K.L.; Carter, E.W.; Jenkins, A.; Dwiggins, L.; Germer, K. Supporting comprehensive, integrated, three-tiered models of prevention in schools: Administrators perspectives. J. Posit. Behav. Interv. 2015, 17, 209–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caplan, G. Principles of Preventive Psychiatry, 1st ed.; Basic Books: Oxford, UK, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, R. An operational classification of disease prevention. Public Health Rep. 1983, 98, 107–109. [Google Scholar]

- Brezinka, V. Zur Evaluation von Präventivintervention für Kinder mit Verhaltensstörungen. Kindh. Entwickl. 2003, 12, 71–83. [Google Scholar]

- Sarimski, K. Verhaltensanalyse. In Diagnostik in der klinischen Kinderpsychologie, 1st ed.; Irblich, D., Renner, G., Eds.; Hogrefe: Göttingen, Germany, 2009; pp. 109–120. [Google Scholar]

- Sarimski, K. Intellektuelle Behinderung im Kindes- und Jugendalter: Psychologische Analysen und Interventionen; Hogrefe: Göttingen, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Janz, F.; Klauß, T. Verhaltensstörungen im Förderschwerpunkt geistige Entwicklung: Möglichkeiten der Diagnostik. Lernen Konkret 2016, 35, 24–28. [Google Scholar]

- Hillenbrand, C. Emotional soziale Entwicklung. In Basiswissen Lehrerbildung: Inklusion in Schule und Unterricht: Grundlagen in der Sonderpädagogik; Lütje-Klose, B., Riecke-Baulecke, T., Werning, R., Eds.; Beltz: Weinheim, Deutschland, 2022; pp. 182–203. [Google Scholar]

- McLeskey, J.; Waldron, N.L. Educational programs for elementary students with learning disabilities: Can they be both effective and inclusive? Learn. Disabil. Res. Pract. 2011, 26, 48–57. [Google Scholar]

- Schürer, S.; van Ophuysen, S.; Marticke, S. Social participation in secondary school: The relation to teacher-student interaction, student characteristics and class-related variables. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2025, 28, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dresing, T.; Pehl, T. Praxisbuch Interview, Transkription & Analyse: Anleitungen und Regelsysteme für Qualitativ Forschende, 8th ed.; Eigenverlag: Marburg, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mayring, P. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse–Grundlagen und Techniken, 13th ed.; Beltz: Weinheim, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Przibilla, B.; Linderkamp, F.; Krämer, P. Subjektive Definitionen von Lehrkräften zu Inklusion–eine explorative Studie. Empir. Sonderpädagogik 2018, 3, 232–247. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, S.; Muckenthaler, M.; Heimlich, U.; Kuechler, A.; Kiel, E. Teaching in inclusive schools. Do the demands of inclusive schools cause stress? Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2021, 25, 588–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böhm-Kasper, O.; Dizinger, V.; Gausling, P. Multiprofessional collaboration between teachers and other educational staff at German all-day schools as a characteristic of today’s professionalism. Int. J. Res. Ext. Educ. 2016, 4, 9–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Three Clusters of Professional Knowledge | Nine Main Categories Distributed Across the Clusters | Number |

|---|---|---|

| Cluster 1: Perception of and Influence on Social Structures | “Perception of social structures”, “Influencing social structures”, “Promoting social and communicative skills” | 1261 mentions |

| Cluster 2: Organization and Framework Conditions | “Framework conditions”, “Class and Team Composition”, “Cooperation”, “Classroom management” | 1244 mentions |

| Cluster 3: Teacher Attitudes | “Pedagogical values and convictions” and “Addressing topics such as disability, diversity, and inclusion” | 346 mentions |

| Differentiation in the classroom | 105 mentions | |

| Unstructured intuitive trial and error | 114 mentions | |

| Diagnostics | 32 mentions | |

| Total | 3102 mentions |

| Main Categories | Tier 1 | Tier 2 | Tier 3 | Total | Number Within the Cluster | Total Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster 1: Perception and Influence on Social Structures | 3102 | |||||

| Influence on social structures | 185 | 232 | 104 | 521 | 1261 | |

| Perception of social structures | 229 | 114 | 47 | 390 | ||

| Promotion of social and communicative skills | 279 | 37 | 34 | 350 | ||

| Cluster 2: Organization and Framework Conditions | ||||||

| Cooperation | 332 | 48 | 211 | 591 | 1244 | |

| Classroom management | 203 | 24 | 54 | 281 | ||

| General conditions | 198 | 25 | 29 | 252 | ||

| Composition of the class and the teaching team | 120 | - | - | 120 | ||

| Cluster 3: Teacher Attitudes | ||||||

| Pedagogical values and convictions | 256 | - | - | 256 | 346 | |

| Addressing topics such as disability, heterogeneity and inclusion | 67 | 18 | 5 | 90 | ||

| Other Categories | ||||||

| Unstructured intuitive trial and error | 20 | 32 | 62 | 114 | ||

| Lesson differentiation | 89 | 10 | 6 | 105 | ||

| Diagnostics | 5 | 2 | 25 | 32 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Köb, S.; Janz, F.; Mühlstädt, P.-M. Social Dynamics Management in Inclusive Secondary Classrooms: A Qualitative Study on Teachers’ Practices to Promote the Participation of Students with Intellectual Disabilities. Disabilities 2025, 5, 85. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities5040085

Köb S, Janz F, Mühlstädt P-M. Social Dynamics Management in Inclusive Secondary Classrooms: A Qualitative Study on Teachers’ Practices to Promote the Participation of Students with Intellectual Disabilities. Disabilities. 2025; 5(4):85. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities5040085

Chicago/Turabian StyleKöb, Stefanie, Frauke Janz, and Paula-Marie Mühlstädt. 2025. "Social Dynamics Management in Inclusive Secondary Classrooms: A Qualitative Study on Teachers’ Practices to Promote the Participation of Students with Intellectual Disabilities" Disabilities 5, no. 4: 85. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities5040085

APA StyleKöb, S., Janz, F., & Mühlstädt, P.-M. (2025). Social Dynamics Management in Inclusive Secondary Classrooms: A Qualitative Study on Teachers’ Practices to Promote the Participation of Students with Intellectual Disabilities. Disabilities, 5(4), 85. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities5040085