Abstract

Film and television play a key role in shaping cultural perceptions of disability, but they often rely on recurring stereotypes that may reinforce stigma and exclusion. Although scholarly interest in this issue has increased, the academic literature remains fragmented and lacks a comprehensive synthesis. This critical review examines how disability is represented through stereotypical portrayals in narrative audiovisual media, specifically scripted films and television series. It synthesizes peer-reviewed studies that explicitly analyze these representations and their narrative or sociocultural functions. The review identifies dominant tropes, theoretical frameworks, and disciplinary approaches while providing a qualitative synthesis of key trends and findings. Although persistent stereotypes are still common, the review also highlights a growing presence of more inclusive and complex portrayals that challenge traditional norms. By providing a structured overview of existing research, this study enhances academic understanding of how disability is depicted on screen and supports efforts to promote more inclusive and accurate representations in popular media.

1. Introduction

1.1. Audiovisual Media and Social Construction

We are currently in the golden age of television fiction and cinema. The growing volume of productions, along with globalization, the internet, and streaming platforms, has amplified the impact of audiovisual products and their ability to shape habits and social customs [1]. Furió Alarcón [2] argues that this impact is rooted in cinema’s capacity to convey messages that gradually influence individual opinions and, over time, society as a whole.

García Amilburu et al. [3] describe a film as a sequence of shots that conveys a discourse about reality. Goyes Narváez [4] expands on this idea, emphasizing that audiovisual culture goes far beyond the use of technology or storytelling; it reconfigures reality through the production of images, sounds, and narrative structures that shape how individuals perceive themselves and others.

In the digital era, audiovisual media connect science, art, and technology, stimulating imagination and generating new knowledge that influences social imaginaries [4]. Thus, cinema and reality maintain a bidirectional relationship: cinema serves as a medium for artists to portray reality, while reality itself is shaped by the norms, values, behaviours, and social models proposed by films and television series [1].

Domingo Moratalla [5], analyzing Julián Marías’ work, states that cinema allows viewers to “gain life experience,” bringing them closer to diverse contexts while providing escapism and comfort [5]. He highlights its potential for human experimentation, for exploring possibilities, and its substantial educational value [5]. This potential, combined with more realistic representations, may help counteract stereotypes and foster the inclusion of people with disabilities.

Images, meanwhile, have been a key element in the social, cultural, and economic development of societies from the late 20th century to the present. Within audiovisual culture, what we consume visually not only stimulates us but also shapes behaviours, consolidates habits, and contributes to the formation of personal and social imaginaries, often reinforcing preexisting stereotypes [6]. In audiovisual content creation, elements such as colour, light, and music play decisive narrative roles that intensify the conveyed message. For example, colour can elicit automatic responses in viewers, with some theorists arguing that specific hues function as somatic triggers [7]. These formal decisions, although subtle, have a direct influence on how viewers interpret and emotionally engage with narratives, affecting how disability and other social issues are portrayed on screen.

1.2. Representation and Discourse in Audiovisual Works

Cinema and the messages conveyed through images can serve as instruments of social control, as numerous productions have depicted specific groups as threats, portraying them as villains within a dichotomous framework of “good versus evil” [8]. This conception of cinema as a shaper of reality is further supported by Aguilar Carrasco [9], who contends that individuals are not born with a predetermined ideology or ethical system; instead, these are constructed from imaginaries and symbols generated by humanity, mainly influenced by immediate environments. This environment—including family, friends, educational institutions, laws, media, and audiovisual narratives—transmits values that operate both visually and implicitly, rendering them difficult to detect through rational analysis. Even when viewers recognize that the content is fictional, its impact persists, as cinema teaches us how to interpret our own reality, delineates what is acceptable and what is not, how we should act, and even with whom we should or should not interact [9].

From this perspective, it becomes imperative to examine the role of stereotypes in shaping social imaginaries. Lippmann, as cited in Lombardinilo [10] (p. 234), defines stereotypes as:

“They are an ordered, more or less consistent image of the world, to which our habits, our tastes, our capacities, our comforts, and our hopes have adjusted themselves.”

This conceptualization underscores the structuring power of stereotypes as cognitive frameworks that simplify social reality and reinforce preexisting belief systems. Exploring how media discourses function as mechanisms of symbolic construction raises the fundamental question of this study: How is disability represented in these audiovisual narratives?

1.3. Theoretical Models of Disability and Their Impact on Representation

There are various perspectives on disability, including the individual, medical, social, and biopsychosocial. The functional diversity model also exists and prioritizes abilities over limitations [11]. This study adopts the definition promoted by CERMI, which supports the use of the term “person with a disability” from a legal and sociological perspective, rejecting euphemistic or stigmatizing expressions [12].

We position ourselves within the biopsychosocial model, aligned with the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) developed by the WHO. This framework classifies health-related factors that influence human functioning and disability [13]. However, despite legislative progress, society still sees disability predominantly through a medical or rehabilitative model. This view favours representations that focus on demonstrating “worth” through exceptionality, neglecting its social dimension [14].

From this perspective, audiovisual representations of people with disabilities tend to be unrealistic and stereotyped. These depictions often reinforce ableist views [14]. Ableism, as a system of oppression, imposes a single vision of the “functional” body, limiting the rights and opportunities of those who do not conform to that norm or hegemonic characteristics [15]. This bias is present in social relationships, families, educational and cultural institutions, and the media [15].

Within this framework, Robbins [16] analyzes how cinema employs “narrative prostheses” such as editing, camera work, sound, and lighting. These elements allow viewers to construct an image of disability in the same way that some people with disabilities use physical prostheses. This audiovisual construction influences social perceptions of normality and differences.

Beyond explicit content, narrative and aesthetic forms also play a role. Hyperrealistic representations may reinforce stigmas. More symbolic or stylized portrayals open spaces for critique and resignification [17].

We consider it essential to address three key aspects. First, the portrayal of families and caregivers, since personal and familial relationships are frequently reflected in audiovisual media [1]. Second is the construction of characters beyond their disability, alongside the lasting impact of the rehabilitative model [14]. Third, visual representations influence how viewers identify with people with disabilities, considering the significant educational potential of audiovisual media [2,3,5].

1.4. Need for a Critical Review

Despite the growing interest in the representation of disability in the media, there is still no critical review that synthesizes the recurring stereotypes present in film and television. Most existing studies focus on specific genres, characters, or productions, which makes it challenging to obtain a global view of the phenomenon. In addition, the wide range of theoretical frameworks spread across disciplines leads to fragmentation, preventing the construction of a coherent narrative about the stereotypes shaping social imaginaries.

This critical review differs from studies such as that of ter Haar et al. [18], which focus on the lived experiences of people with disabilities regarding their public representation. While that study analyzes subjective perceptions of social discourses, the present work focuses on the narrative content of audiovisual media itself—films and television series—as cultural texts. Its goal is to explore recurring representational patterns, the conceptual categories used in the literature, and the common traits in how disability is portrayed. These two approaches are complementary: one addresses the impact of representations, while the other analyzes their construction.

We therefore begin with the hypothesis that the representation of characters with disabilities in audiovisual media significantly influences the construction of social imaginaries either by reinforcing stereotypes or by promoting inclusive attitudes, thereby shaping how non-disabled people relate to the disability community.

In this study, the concept of inclusive and accurate representation is not treated as a fixed or universal category, but rather as a dynamic and evolving construct shaped by cultural, political, and social contexts. Inclusive representation refers to portrayals that move beyond stereotypical or reductionist frameworks, presenting people with disabilities as complex, diverse, and active individuals. This involves recognizing disability not merely as an individual condition, but as a social construct shaped by broader cultural narratives and ideological structures [14].

From this perspective, inclusive representation rejects both victimization [16] and idealization [14]. Instead, these portrayals promote narratives centred on autonomy, self-determination, and the plurality of lived experiences, which align with the guidelines of the social model [11]. Simultaneously, accurate representation is not confined to clinical precision. Still, it concerns the extent to which audiovisual narratives reflect the structural and societal conditions that shape the experience of disability [15]. This includes portrayals that avoid equating disability with “otherness” [16] and instead offer critical, socially aware perspectives.

This approach aligns with the social and human rights models of disability, which shift the analytical focus away from the “damaged” body and toward the environments and systems that sustain exclusion and dependence [11]. Therefore, the analysis presented here does not evaluate representations based on literal or medical accuracy, but rather on their potential to foster more equitable and critical discourses in media and their faculty to transform collective imaginaries.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Theoretical Framework

This review adopts a qualitative, integrative approach to synthesize academic literature on stereotyped representations of disability in audiovisual media. The aim is to critically examine how disability stereotypes have been approached across disciplines, identify recurring tropes, and reflect on the theoretical and cultural frameworks used to interpret them. This approach is especially suitable for mapping a fragmented and interdisciplinary field, enabling the organization of dispersed insights and the identification of key trends and research gaps.

To ensure methodological transparency, we followed a multi-step process involving the definition of research questions, the development of comprehensive search strategies, the selection of peer-reviewed sources based on predefined criteria, and the qualitative analysis of the resulting literature. Rather than offering a quantitative assessment of study quality, this review emphasizes conceptual contributions, recurring themes, and interpretive frameworks present across the literature.

To maintain academic rigor and transparency, we established clear inclusion and exclusion criteria to guide the literature selection process, drawing on principles commonly recommended for evidence synthesis in qualitative research settings [19]. These criteria ensured that the selected articles focused specifically on the representation of disability in fictional films or television content and engaged in critical or narrative analysis. Studies focusing exclusively on news, documentary, advertising, or non-narrative formats were excluded. This approach supports a structured overview of how stereotypes related to disability have been examined in audiovisual media and offers a foundation to guide future research.

2.2. Analytical Focus and Identification of Research Questions

This critical literature review aims to examine how academic studies have addressed the representation of people with disabilities in audiovisual media, with a particular emphasis on the use of stereotypes and the conceptual frameworks that underpin such analyses. The goal is not only to identify patterns but also to critically assess how these patterns have been theorized and interpreted across academic literature.

To structure this review, the following research questions guide the critical analysis: (1) What stereotypes have been identified in the representations of characters with disabilities in audiovisual media? (2) What theoretical and conceptual approaches have been used to analyze these representations? (3) What genres, themes, and character traits predominate in audiovisual works representing disability? (4) What gaps or limitations does the literature identify regarding the representation of disability in audiovisual products?

2.3. Literature Search Strategy

To support a critical analysis of how disability is represented in audiovisual media, relevant academic studies were identified through a purposive selection strategy. The focus was on literature examining characters with disabilities in film and television, with particular attention to how these representations engage with stereotypes and narrative or symbolic discourses. The academic studies were selected if they addressed characters with disabilities and their representations in audiovisual works, whether films or television series. No restrictions were applied regarding the type of disability represented, including physical, sensory, intellectual, or psychosocial conditions.

Regarding the core concepts, the studies had to focus on the media representation of disability, emphasizing stereotypes, visual or symbolic discourses influencing social perception. Research addressing ableism and the narrative use of disability was also included.

This study was limited to narrative audiovisual productions in film and television (movies, series, soap operas, and miniseries), excluding video games, documentaries, reality shows, news content, social media, and literature.

The search strategy was designed to locate pertinent scholarship. Boolean operators (“AND,” “OR”) were used to design queries tailored to the syntax of each database. Searches were conducted in June 2025 across Scopus, Web of Science (all collections), and ERIC, in both English and Spanish. These sources were selected due to their scope, academic quality, multidisciplinary coverage, and ability to retrieve both consolidated literature and recent studies not yet formally indexed.

For each research question, a specific search string was developed with the support of artificial intelligence tools (ChatGPT), resulting in a total of 12 strings (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Database Query Strategies.

Additionally, a complementary manual search was conducted to ensure the exhaustiveness of the corpus, using broader terms such as “disability,” “representation,” and “film and stereotypes.” Citation tracking and reference checking of the included studies were also performed.

In total, 58 articles were retrieved through this manual search, which were included in the screening process under the same conditions as those retrieved from the databases (a total of 960 records before applying filters).

2.4. Study Selection Process

The study selection process was organized into several consecutive stages, conducted by the three authors, who combined automated filters with manual screening according to predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 2).

Table 2.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria.

The initial automatic filtering of search results limited the records to the English and Spanish languages, open access, and a period between 2015 and 2025. This preselection reduced the records from 960 to 180 (from databases) and from 58 to 41 (from the manual search), resulting in a total of 221 records. The methodological decision to limit the time frame was based on the increase in audiovisual productions featuring characters with disabilities since the 2010s, as noted by García-Borrego and González-Cortés [20].

Subsequently, all results were exported to Mendeley to remove duplicates, reducing the corpus to 172 studies (131 from databases and 41 from manual search). A two-phase manual review was then conducted: first, titles and abstracts, followed by full-text screening. Each author independently reviewed the studies to minimize the risk of bias, achieving 97.7% agreement (168 texts), and disagreements were resolved by consensus.

Eligible studies included research using qualitative, quantitative, or mixed methods analyzing representations of disability, stereotypes, or visual discourses, including conceptual frameworks such as ableism or disability models. Studies focusing solely on subjective perceptions without analyzing audiovisual content, as well as publications lacking empirical grounding, duplicates, incomplete, or inaccessible works, were excluded.

Only peer-reviewed studies were included. In the case of grey literature, only doctoral theses available in institutional repositories were considered, excluding undergraduate and master’s theses.

During the manual review of titles, 90 studies were excluded. Of the 82 remaining abstracts, 40 were removed for the following reasons: 22 did not address audiovisual representations of disability, 14 analyzed other types of media, 2 were master’s theses, and 2 lacked a clear methodology.

A total of 42 full-text studies were assessed. Three were excluded: one was inaccessible, and two doctoral theses could not be processed in MAXQDA (version 24). Finally, 39 studies [21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59] were included in the synthesis.

The total number of selected studies is summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow Diagram of the Study Selection Process.

2.5. Data Selection and Extraction

After screening and selecting the final set of studies, key bibliographic information—such as authorship, year of publication, country, journal, and SJR quartile—was extracted into an Excel spreadsheet to support comparative analysis. These data are presented in the Results section to provide context about the academic landscape of the field.

In parallel, a qualitative coding process was conducted using MAXQDA software. The coding scheme focused on aspects such as the type of disability represented and the recurrence of specific stereotypes. The analysis followed a primarily deductive logic, guided by the research questions and theoretical background, while remaining open to inductively emerging categories identified through a close reading of the texts.

2.6. Thematic Analysis and Synthesis

A qualitative thematic analysis was used to synthesize the content of the included studies and identify significant patterns in the representation of disability in audiovisual works.

The studies were classified according to audiovisual production type, genre, methodology, disability represented, identified stereotypes, conceptual frameworks used, and other relevant communicative aspects. This categorization supported the development of a structured narrative on how disability stereotypes are constructed and discussed in academic literature.

Across the 39 analyzed studies, 883 coded segments were identified. The coding hierarchy is presented in tabular format (Table 3) to provide a compact and comprehensive view of the entire analytical structure. Additionally, artificial intelligence (specifically ChatGPT) was used solely as a support tool to generate preliminary drafts of the coding matrix, which were thoroughly reviewed and refined by the researchers.

Table 3.

Hierarchical Structure of Coding Categories Used for Thematic Analysis of the Selected Studies (Excel, using data from MAXQDA).

3. Results

This section presents the findings obtained from the review of the 39 articles included in the analysis. Following an initial overview that outlines the characteristics of the selected studies, the results are organized into thematic blocks that address our research questions. The thematic coding developed in MAXQDA enabled us to structure the corpus around analytical categories related to these questions, including the characteristics of the studies, the types of disabilities represented, the identified stereotypes, and the theoretical frameworks used to analyze these representations. This classification aims to provide an extensive and systematic understanding of how disability is represented in audiovisual works, as well as the ideological frameworks that shape these representations.

3.1. Characteristics of the Studies

A total of 39 studies [21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59] were analyzed in the final synthesis. These works span a publication period from 2015 to 2025 and examine representations of disability in narrative audiovisual products, including films and television series. The studies exhibit notable geographical and methodological diversity and have been published in peer-reviewed scientific journals with varying levels of indexing, as indicated by the SJR quartile.

Table 4 presents the main bibliographic characteristics of the included studies, organized by authorship, country of the journal’s publication, analyzed medium, type of disability represented, journal title, and SJR quartile (when applicable).

Table 4.

Bibliographic Characteristics of the Studies Included in the Corpus [21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59].

As shown in Table 4, the final corpus of 39 studies presents considerable geographical and contextual diversity. The articles analyze works from a total of 17 countries, with Spain (n = 10), the United States (n = 9), the United Kingdom (n = 8), and India (n = 5) being the most represented. Most studies originate from middle- to high-income contexts, which may influence the cultural frameworks from which disability representation is approached.

Regarding language, English predominates, particularly in studies published in indexed journals. However, Spanish-language articles from Spain and Latin America were also included, enriching the linguistic diversity of the corpus.

With respect to the indexing level of the journals according to the SJR indicator, 85% of the reviewed articles were published in journals with an identified quartile: 11 studies in quartile 1 (Q1), 14 in quartile 2 (Q2), 7 in quartile 3 (Q3), and 1 in quartile 4 (Q4). In six cases, it was not possible to determine the quartile due to a lack of updated information or publicly available data.

3.2. Stereotypes of Disability in Audiovisual Media

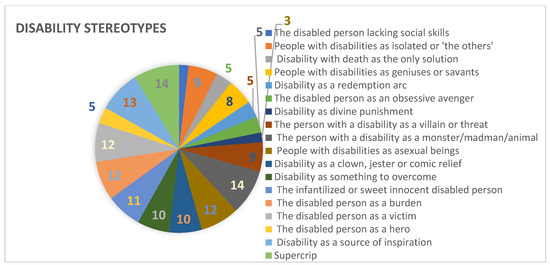

One of the central questions of this review was to identify the most frequent stereotypes in the representation of disability in films and television series. To this end, the descriptions and critical assessments provided by the studies about the represented characters were analyzed, with these references thematically coded using MAXQDA (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Disability Stereotypes Used in Media (Excel, using data from MAXQDA).

A total of 21 different stereotypes—both negative and positive—were identified. The most recurrent was the Supercrip stereotype (n = 14), which portrays people with disabilities as heroic figures who overcome their limitations through individual effort, even acquiring extraordinary abilities. Although sometimes perceived as positive, this figure reinforces ableism by requiring exceptional achievements to grant social value [21,22,23]. This archetype is familiar in superhero films or in stories where characters possess supernatural abilities that “compensate” for their disability [21,24,25].

Also, with 14 mentions, the stereotype of people with disabilities as monstrous, dangerous, or dehumanized figures stands out, associated with villains, criminals, or unstable individuals, as noted by Álvarez Ramírez, Solís García, and Kramer [15,26,27]. Some characters, such as the antagonist in Don’t Breathe, are not even given names, as Wischert-Zielke [28] points out, which accentuates their depersonalization.

The third most frequent stereotype, with 13 mentions, was the representation of disability as a source of inspiration for non-disabled people. In this pattern, characters serve as catalysts for others’ personal growth, as reported by Maestre Limiñana, Gauci and Callus, and Lopera-Mármol et al. [22,29,30,31].

The stereotype of the unsexualized character (n = 12) reflects the presumed inability to engage in romantic or sexual relationships, often overlapping with the “sweet innocent” figure (n = 11). Examples can be found in Oasis [32] and in analyses of the original version of The Little Mermaid [33].

Another frequent pattern was that of the passive victim (n = 12), depicted as defenseless or resigned to their fate [34,35,36]. Related to this is the stereotype of disability as a burden on the surrounding environment, especially within the family context [37,38,39].

Finally, the stereotype of the person with a disability whose death is seen as a narrative resolution was identified, as in The Sea Inside, where the disabled body is portrayed as a prison [22].

Overall, these stereotypes reveal a narrative focused on exceptionality, suffering, or otherness, which reinforces ableist imaginaries. Although some authors highlight progress toward more positive representations, the identified patterns reveal limited diversity and underscore the need for more inclusive and nuanced discourses [36].

3.3. Theoretical and Conceptual Approaches

The second research question focused on identifying the theoretical approaches used to analyze audiovisual representations of disability. Although the frameworks were diverse, two lines of analysis stood out for their frequency and cross-cutting relevance (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Theoretical Approaches Are Most Mentioned (Excel, using data from MAXQDA).

The most frequent approach is ableism, explicitly mentioned in 12 of the analyzed documents. On multiple occasions, the queer-crip approach, a more critical perspective, is further highlighted within the corpus, as cited in several studies, including those by García León and García León [40,41]. As discussed in the theoretical framework, ableism refers to social, institutional, political, cultural, and educational structures that discriminate against people with disabilities for the mere fact of “being.” This approach emphasizes how audiovisual products legitimize the duality between people with and without disabilities, privileging bodily and cognitive normativity. In some cases, it is complemented by references to the social model of disability, which shifts the focus from the body to the environment and symbolic barriers.

Other works rely on concepts such as the disabled body or the notion of narrative prosthesis (Figure 4) to interpret the role of disability in the plot as a symbolic or structural resource, appearing 12 times across all studies. These approaches highlight how disability functions as a metaphor, obstacle, or element of narrative transformation. Studies such as those by Wang-Xu [42] or Biernoff [43] explore how the disabled body is constructed as the “other” within visual frameworks that reproduce binaries between normality and deviance.

Figure 4.

Visual Representation of the Concept of “Narrative prosthesis” and Corporality (MAXQDA).

Finally, although excluded from this review selection because his seminal work, The Cinema of Isolation, was published in 1994 and therefore falls outside the study’s time frame, Martin F. Norden was cited in eight studies as a key reference in the cinematic analysis of disability. Within disability media studies, he is widely recognized as one of the first scholars to examine how disability is portrayed in film, highlighting how audiovisual productions have historically relegated people with disabilities to a position of otherness while reinforcing societal norms surrounding disability. Norden argued that cinematic representations of disability are inherently ideological [22,25]. His work made a significant contribution to the field by proposing the first categorization of disability archetypes in cinema, some of which remain relevant today. Norden also became relevant due to his contributions to establishing an analytical framework that helps explain how certain bodies are privileged over others [23,28]. Nevertheless, his work has also been subject to criticism [43].

3.4. Genres, Themes, and Character Traits

The third research question addressed the genres of the productions, themes, and characters. In the reviewed studies, no emphasis was made on the personal characteristics of the characters; therefore, this section discusses the type of production (whether films, series, or both), the film industry in which it was produced, the genre of the audiovisual work analyzed, and the type of disability represented.

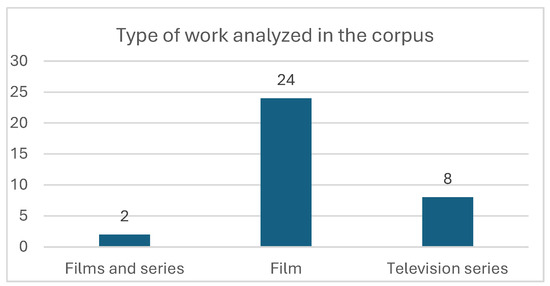

Most studies examined films (n = 24), followed by television series (n = 8) and combined analyses (n = 2) [44]. The remaining five studies did not specify the type of production, focusing instead on character analysis itself (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Type of Work Analyzed in the Corpus (Excel, using data from MAXQDA).

Regarding origin, 26 productions were Western, 7 came from Hindi or Arab industries, and 3 were independent. The remaining 3 studies focused on identifying characters with specific types of disabilities, without specifying the industry of the productions analyzed [45,46,47] (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Industry that Produced the Works Analyzed (Excel, using data from MAXQDA).

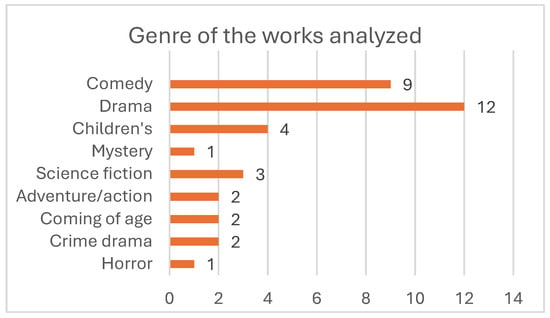

Regarding genre, dramatic productions predominated (n = 12), followed by comedies (n = 9), children’s films (n = 4), science fiction (n = 3), action/adventure and coming-of-age (n = 2 each), and finally mystery and horror (n = 1). Three studies did not specify the genre (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Genre of the works analyzed (Excel, using data from MAXQDA).

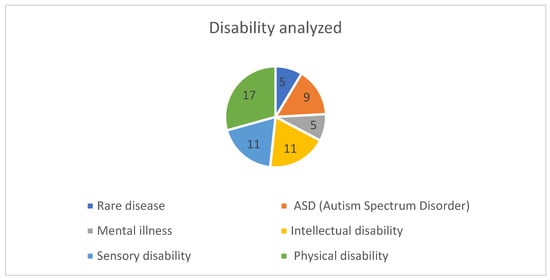

Finally, the most frequently represented type of disability was physical disability (n = 17), followed by intellectual and sensory disabilities (n = 11 each), autism spectrum disorder (n = 9), and rare and mental illnesses (n = 5 each) (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Disability Analyzed (Excel, using data from MAXQDA).

3.5. Gaps and Limitations Highlighted by Studies

As a conclusion to our research questions, many of the studies included in this review point to more positive trends in these representations, as noted by Lopera-Mármol et al. [48] and Wohlmann and Harrison [49]. However, the limited representation of certain disabilities, such as rare diseases [50] or stuttering [51], is also noteworthy. As shown in the previous section, visually recognizable disabilities, such as physical or sensory ones, predominate to the detriment of intellectual disabilities or mental illnesses, thus continuing to reproduce negative stereotypes.

Several studies also highlight the lack of intersectionality in the analyzed narratives. Characters with disabilities are rarely portrayed as simultaneously being women, racialized individuals, LGBTQIA+, older adults, or from disadvantaged social classes. This omission reinforces a view of disability as a circumstance affecting only white, cisgender, heterosexual men from middle-class families, as indicated by Aspler et al. [39], Deb [52], and Dean and Nordahl-Hansen [46], thus failing to reflect the diversity of this phenomenon.

Regarding the research itself, some authors point out that many current studies on media representations focus on a specific type of disability [48]. There is also a lack of empirical work, including representations created by members of the disability community, such as the study analyzed by Carter-Long [53]. Tharian et al. [44] stated that characters were significantly richer when their creators belonged to the community, or in the case of productions, when portrayed by actors and actresses with disabilities—a gap in the film industry also identified by Aspler et al. [39] and Zaptsi et al. [36].

These gaps highlight the need for continued research that adopts broader, intersectional, and participatory approaches, contributing to a more plural, critical, and realistic representation of disability in audiovisual media, while also fostering the artistic expression of people with disabilities [53].

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings

The analysis provides an overview of the current state of research on disability stereotypes in audiovisual products. Based on the synthesis of 39 studies, recurrent patterns were identified in the theoretical approaches employed, the predominant narrative genres, the characteristics of the represented characters, and the primary limitations of the field.

The most frequent stereotypes—such as the Supercrip, the inspirational figure, the monster, or the victim—continue to occupy a prominent place in disability representations. These patterns reinforce normative and ableist perspectives, in which disability is portrayed as an exceptional condition, emphasize the binary distinction between people with and without disabilities, and depict the disabled body as abject or morbid [22]. The persistence of these stereotypes reinforces scholarly observations about the reductive and emotionally manipulative nature of media narratives surrounding disability. Nevertheless, numerous more inclusive representations aimed at diverse audiences have emerged [54,55], suggesting that significant progress is indeed being made. These findings underscore the continued need for inclusive and accurate representations that move beyond these limiting portrayals and reflect the diversity and complexity of disability experiences, as proposed in the conceptual framework of this study.

4.2. Predominant Theoretical Approaches

Regarding analytical approaches, most studies adopt critical perspectives linked to ableism and the social model. However, there are also explicit references to the rehabilitative model—addressed from a critical standpoint and emphasizing the need to avoid falling back into it.

Symbolic or narrative frameworks, such as the disabled body or narrative prostheses, were also identified, offering interpretations of how disability holds substantial symbolic value. By merely visualizing the disabled body, it can be stripped of its negative connotations and redefined as a metaphor of beauty and desire [40,42].

4.3. Genres, Themes, and Character Representation

Regarding the characteristics of works and characters, there was a clear concentration in dramatic fiction productions, with a predominance of characters with physical or sensory disabilities, consistent with the findings of García-Borrego and González-Cortés [20]. Intellectual or psychosocial disabilities, as well as intersections with gender, age, race, or social class, are scarcely represented [48,52,56], which may limit the accuracy of these portrayals or their potential use as adequate educational resources, as noted by Deb [52], Ressa [38], and Solís García [26].

This concentration may suggest a narrowing of narrative possibilities. The predominance of dramatic productions increases the risk of reinforcing stereotypes. These include portraying people with disabilities as victims, depicting disability as a burden, or framing death as the only resolution. As a result, characters with disabilities are often constructed as passive subjects resigned to their circumstances, merely victims of their condition—offering a reductive vision of the disability experience.

These portrayals, centred on dramatism, may contribute to the perpetuation of a social image in which people with disabilities are seen as dependent and helpless, a perception which might reinforce paternalistic attitudes in real life. It also supports the notion that a life with disability is not worth living, as members of this group are perceived as incapable of developing or leading a meaningful existence.

Repeatedly featuring physical or sensory disabilities renders other conditions—less known to the public or not immediately visible—invisible, even though they equally deserve attention, representation, and visibility. By relying on a narrow, stereotyped image of disability, certain forms are being prioritized over others, often favouring those more socially accepted. This approach not only limits the creative and narrative scope of fiction but also denies its transformative potential, contributing to systemic neglect and the reproduction of ableist narratives [15] and undermining the capacity of fiction to function as a vehicle for cultural change. Addressing this issue requires a shift toward inclusive and accurate representations, which portray disabled individuals as autonomous and multidimensional, rather than as narrative devices confined to stereotypes.

Concerning the producing industries, the fact that such stereotypes are reproduced in both Western and Hindi or Arab industries [25,57,58,59] may suggest that this is a cross-cultural issue.

Regarding themes and character representation, it is essential to analyze how families are portrayed. Our findings suggest that these portrayals are often closely connected to the stereotype of the person with a disability as either a burden or someone needing special protection. Family members or primary caregivers are frequently shown as emotionally drained and perpetually anxious, as noted by Aspler [39], Dean [46], and Ressa [38]. Martos Contreras [37], for instance, analyzed a work where the character with a disability was treated with contempt by his daughters, further emphasizing the persistence of biased depictions of caregiving and family dynamics.

However, there are signs of progress. In her analysis of eight characters, Sanz-Simón [54] reported that two were portrayed as autonomous individuals who actively participated in family life within environments characterized by respect and affection, where relationships were not defined by disability.

4.4. Identified Gaps and Future Research Directions

While many of the reviewed studies analyzed predominantly focus on the presence of stereotypes in audiovisual narratives, they often overlook the personal characteristics of characters with disabilities—such as their profession, socio-affective life, hobbies, or interpersonal relationships.

Another aspect mentioned in the introduction but absent from the results is the issue of audience identification with characters with disabilities. The reviewed works do not examine how these characters are constructed in relation to emotional impact or viewer engagement, nor do they explore the types of identification or reactions they are intended to elicit. The role of visual framing in shaping audience identification, including how cinematographic techniques foster empathy or create distance, remains largely unexplored.

The included studies highlight relevant gaps, including the lack of intersectional perspectives [27,35,41,48] and the limited participation of people with disabilities in creating their own stories or appearing on camera [30,36,53]. These aspects open future research lines focused on access to representation, the social perspective from which these portrayals are constructed, and the need to involve the perspective of people with disabilities.

Additionally, future research could investigate how stereotype patterns vary across different media formats, as this dimension was not explored in the present review.

Reframing Stereotypes: Analytical Limitations and Critical Considerations

Some stereotypes tend to overlap; for example, the portrayal of a person with a disability as isolated often coincides with depictions of individuals lacking social skills. Together, these tropes contribute to a profoundly negative image, implying that people with disabilities are unfit to participate in social life fully. Such narratives can influence how non-disabled viewers interact with the disability community, while also undermining the self-esteem and self-perception of disabled individuals. These connotations are closely linked to other harmful tropes, such as the notion that people with disabilities are “better off dead” or represent a “burden” to their families. Collectively, these stereotypes reinforce social isolation, dependency, and a reductionist view of disability that limits personal development and reduces the individual to their condition.

So-called “positive” stereotypes such as the supercrip, the inspirational hero, or the disabled genius also carry problematic implications. These portrayals often suggest that people with disabilities are only valuable when they accomplish extraordinary feats. For disabled audiences, this can foster a constant need for validation; for non-disabled viewers, it reinforces the idea that disability is acceptable only when accompanied by exceptional talent, and they can be a source of inspiration or motivation. This implicit demand for heroism can be psychologically exhausting and may subtly reinforce exclusion.

Although this study offers a structured overview of how disability is represented in media, it does not capture the full complexity of the phenomenon. While thematic analysis helped identify major patterns, more nuanced or contradictory discourses may have been overlooked. The findings, in fact, reveal the coexistence of both inclusive and stigmatizing representations, reflecting uneven progress in terms of narrative diversity and accuracy.

An intersectional perspective is essential to understanding these dynamics. Disability is still predominantly portrayed as a condition affecting cisgender, middle-class men. When women with disabilities appear, they are often infantilized, reinforcing a dual layer of discrimination based on both gender and ability. Similarly, the overrepresentation of physical disability in audiovisual narratives contributes to repetitive storytelling and the marginalization of other equally valid experiences. For instance, the worldview of a wheelchair user cannot be equated with that of someone living with schizophrenia. Disability is a plural and heterogeneous reality, and media representations should reflect this diversity, encouraging both identification within the community and broader understanding among the general public.

One of the most significant challenges lies in the difficulty of clearly defining and consistently applying the notions of “inclusive” and “accurate” representation. These concepts are culturally contingent and not easily operationalized. Future research could investigate how different audiences interpret these portrayals and undertake cross-format and cross-cultural comparisons to better understand the narrative mechanisms underlying disability representation.

Finally, these findings highlight a broader tension within disability media studies: the analytical focus on identifying recurring stereotypes often overshadows the narrative, relational, and ideological dimensions of representation. While typologies help detect patterns, they risk flattening the complexity of characters and the sociocultural contexts in which such representations emerge. The repeated identification of tropes, such as the victim or the burden, may reflect not only media conventions but also methodological limitations within the field. These imitations often overlook elements such as character development, narrative structure, emotional resonance, and audience reception.

4.5. Study Limitations

This study presents some limitations inherent to the review methodology. First, although studies in English and Spanish were included, the search was limited to specific academic databases. It did not include literature in other languages or exhaustive searches of grey literature beyond accessible doctoral theses. This may have excluded relevant studies from different cultural or linguistic contexts.

Additionally, the analysis focused exclusively on what was reported in the included articles; therefore, the results largely depend on the approaches and level of detail provided by the cited authors.

Finally, coding and interpretation were conducted from a single research perspective, which may have influenced specific readings or thematic emphases. This was also affected by the generalization of some coding categories, which may have been biased due to the impossibility of delving into minute details, despite constant efforts to systematize the information through the analytical tool employed.

One of the most significant limitations of this study is its lack of consideration for differences between media production formats. Consequently, it does not examine potential variations in the identified stereotypes based on the audiovisual context or type of media format. This gap is essential, as different forms of media representation involve distinct narrative conventions and shape specific audience expectations. As a result, the analysis may be partially biased, limiting our ability to fully understand the potential impact of these representations on viewers and their relationship with the disability community.

However, this limitation also suggests a promising direction for future research. Subsequent studies could expand the scope by exploring whether these stereotypes are pervasive across formats, appearing consistently not only in narrative audiovisual media (as examined in this article) but also in other media types, such as social media content or television news broadcasts.

5. Conclusions

This study aimed to map the current state of academic research on the representation of disability, primarily in narrative audiovisual works (mainly films and series), based on an analysis of 39 studies published between 2015 and the present, using an ad hoc coding matrix created by the three researchers.

The findings show that representations remain dominated by classic stereotypes, such as the Supercrip, the victimization of disability, or desexualisation. However, the theoretical approaches used to analyze these representations are strongly critical of the rehabilitative model and ableism, reflecting an academic interest in adopting critical perspectives and questioning established paradigms that have shaped the field since its inception in the 1980s. Additionally, there is a growing line of research on the use of disability as a narrative element and on the use of disabled bodies as devices that draw the viewer’s attention by highlighting “what they are not” (while ignoring the fact that anyone could become part of this community at any point in life).

Representations continue to focus on obvious and normatively profiled disabilities, overlooking the fact that disability is a cross-cultural and intersectional phenomenon, affecting racialized, transgender, and non-heteronormative individuals, as well as those living in low-income countries. This lack of perspective is reinforced by the fact that the Western market, particularly the American industry, is the largest producer of disability-related works, excluding other markets such as Hindi cinema or independent films.

Another major critique is the predominance of drama as the preferred genre, as it tends to favour victimizing or pitiful portrayals where the character’s entire plot revolves around their disability. Little attention is paid to what motivates these characters or what they aspire to achieve (beyond overcoming barriers imposed by their disability). In other words, the focus is often on “what they are” rather than “who they are,” without portraying the everyday lives of people with disabilities who want to exist without being portrayed as examples to follow or as everyday superheroes.

As a solution to this issue, several authors cited in this study, such as Carter-Long [53] and Aspler et al. [39], stress the urgent need to place people with disabilities both in front of and behind the camera, as those who live these realities are the ones best equipped to tell them realistically. While academia may not directly fulfil this premise, it can encourage more inclusive, intersectional, and contextualized research that incorporates alternative theoretical models, new voices, and narrative formats through education. For future research, we suggest developing tools that invite reflection on the role of media in shaping the social construction of disability, guided by frameworks of inclusive and accurate representation. Such approaches can contribute to the generation of more plural, realistic, and transformative imaginaries. These tools could be applied to educational practices, helping to generate slight changes that, ideally, may plant the seeds for structural transformation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.G.G., C.F. and A.R.A.-G.; methodology, A.G.G., C.F. and A.R.A.-G.; validation, C.F. and A.R.A.-G.; formal analysis, A.G.G.; investigation, A.G.G.; resources, C.F. and A.R.A.-G.; data curation, A.G.G.; writing—original draft preparation, A.G.G.; writing—review and editing, C.F. and A.R.A.-G.; visualization, A.G.G.; supervision, C.F. and A.R.A.-G.; project administration, C.F. and A.R.A.-G.; funding acquisition, C.F. and A.R.A.-G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the University of León (Spain), through its own Predoctoral Grants Program, in the 2024 call for applications.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No publicly available datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study. The data are stored on the authors’ personal devices and are available upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT (OpenAI, GPT-4) as a support tool exclusively for technical and organizational purposes, such as drafting preliminary versions of the coding matrix and suggesting search strings for database queries. All outputs generated by the tool were carefully reviewed, validated, and refined by the authors, who take full responsibility for the final content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study, in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Disability Language/Terminology Positionality Statement

This study employs both person-first and identity-first language, depending on the terminology used in the original articles analyzed. This decision was made to maintain fidelity to the language choices of each author and their cultural context, while also respecting the diversity of perspectives within the disability community. Additionally, in our own writing, we primarily use person-first language (e.g., “person with a disability”) as it aligns with widely accepted norms in Spanish-speaking academic and legal frameworks. However, we acknowledge that identity-first language is increasingly embraced within some disability movements, particularly among those who view disability as a central and empowering part of their identity. Our: intention is to approach disability respectfully and critically, avoiding deficit-based narratives and embracing inclusive and socially oriented frameworks such as the social model and the concept of ableism.

References

- Salar Sotillos, M.J. Cine, realidad social y educación. Docencia y Derecho 2021, 7, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furió Alarcón, A. Cinema, a Tool for Social Change. Eur. Public Soc. Innov. Rev. 2024, 9, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Amilburu, M.; De Santiago Ruiz, P.; Orte García, J.M. El Cine En 7 Películas. Guía Básica Del Lenguaje Cinematográfico; UNED: Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia: Madrid, Spain, 2017; ISBN 978-84-362-7234-5. [Google Scholar]

- Goyes Narváez, J.C. Audiovisualidad, Cultura Popular e Investigación-Creación. Cuad. Cent. Estud. Diseño Comun. 2020, 79, 103–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo Moratalla, T. Figurarse La Vida. A Propósito de La Antropología Cinematográfica de Julián Marías. THÉMATA Rev. Filos. 2012, 46, 517–527. [Google Scholar]

- Osácar Marzal, E. La Imagen Turística de Barcelona a Través de Las Películas Internacionales. PASOS Rev. Tur. Patrim. Cult. 2016, 14, 843–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramesco, C. Colores de Cine: La Historia Del Séptimo Arte En 50 Películas; Blume: Barcelona, Spain, 2023; ISBN 978-84-100-4819-5. [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez Couto, D. Imágenes Del Control Social. Miedo y Conmoción En El Espectador de Un Mundo Bajo Amenaza. Re-Visiones 2024, 5. Available online: https://revistas.ucm.es/index.php/REVI/article/view/94597 (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- Aguilar Carrasco, P. El Papel de La Mujer En El Cine; Santillana Educación: Madrid, Spain, 2017; ISBN 978-84-141-0839-0. [Google Scholar]

- Lombardinilo, A. La Transformación de Las Noticias: Walter Lippmann y La Opinión Pública. Rev. Estud. Socioeducativos RESED 2023, 11, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez Dalmeda, M.E.; Chhabra, G. Modelos teóricos de discapacidad: Un seguimiento del desarrollo histórico del concepto de discapacidad en las últimas cinco décadas. Rev. Esp. Discapac. 2019, 7, 7–27. Available online: https://www.cedid.es/redis/index.php/redis/article/view/429 (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- Gascón-Cuenca, A.; Bernabé Padilla, I.; Hernández Azcón, A.; Ramos Miralles, A.; Martínez Trigo, A.; Martínez Cameros, C.E.; Costa Navarro, D.; Jusue Moñino, N.G.; Muñoz Ruíz, R.; Fierrez Soria, S.; et al. El Ordenamiento Jurídico Español y Las Personas Con Discapacidad: Entre La Autodeterminación y El Paternalismo. Clínica Juríd. Justícia Soc. Inf. 2021, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organización Mundial de la Salud. ICF: The International Classification of Functioning Disabilities and Health: Short Version; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2001; p. 228. ISBN 92-4-154544-5. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez Díaz, S.; Sánchez Padilla, R.; Ferreira, M.A.V. La Discapacidad Como Diversidad Funcional: Imágenes de Una Construcción Social. Intersticios Rev. Sociológica Pensam. Crít. 2024, 18, 7–33. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez Ramírez, G.E. El Capacitismo, Estructura Mental de Exclusión de Las Personas Con Discapacidad; CERMI, Ed.; Ediciones Cinca: Madrid, Spain, 2023; ISBN 978-84-18433-67-2. [Google Scholar]

- Robbins, J. Violencia, género y discapacidad: La ideología de la normalidad en el cine español. Hispanófila 2016, 177, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carney, J. Culture and Mood Disorders: The Effect of Abstraction in Image, Narrative and Film on Depression and Anxiety. Med. Humanit. 2020, 46, 430–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ter Haar, A.; Hilberink, S.R.; Schippers, A. Lived Experiences of Public Disability Representations: A Scoping Review. Disabilities 2025, 5, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Cortes, O.D.; Betancourt Núñez, A.; Bernal Orozco, M.F.; Vizmanos-Lamotte, B. Scoping Reviews: Una Nueva Forma de Síntesis de La Evidencia. Investig. En Educ. Medica 2022, 11, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Borrego, M.; González-Cortés, M.E. Cultural Journalism and Disability in Cinema: A View of Its Historical Evolution through Specialized Critique. Vis. Rev. Int. Vis. Cult. Rev. Rev. Int. Cult. Vis. 2022, 11, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahn, C.W. Marketing the Prosthesis: Supercrip and Superhuman Narratives in Contemporary Cultural Representations. Philosophies 2020, 5, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maestre Limiñana, S. La Mirada Rehabilitante En Campeones y Mar Adentro. Rev. Esp. Discapac. 2024, 12, 241–252. Available online: https://www.cedid.es/redis/index.php/redis/article/view/1032 (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- Martausová, M. Authenticity in Representations of down Syndrome in Contemporary Cinema: The “Supercrip” in the Peanut Butter Falcon (2019). Ekphrasis 2021, 25, 26–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaji, S.; C, S. Challenging conventional heroism: Redefining heroism through the representation of disabled superheroes in daredevil and x-men. ShodhKosh J. Vis. Perform. Arts 2023, 4, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawande, V.; Kashyap, G. Discovering Impaired Superheroes in Hindi Movies: A Study of Characterization of Disabled in Movies and Its Impact on Their Social Life. Community Commun. Amity Sch. Commun. 2017, 5, 52–59. [Google Scholar]

- Solís García, P. La Visión de La Discapacidad En La Primera Etapa de Disney: Blancanieves y Los 7 Enanitos, Alicia En El País de Las Maravillas y Peter Pan. Rev. Med. Cine 2019, 15, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, R. Crime Media as Cinematic “Freak Show”: Ableism and Speciesism in Retelling Dahmer. Crime Media Cult. 2024, 20, 388–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wischert-Zielke, M. The Impulse-Image of Vampiric Capital and the Politics of Vision and Disability: Evil and Horror in Don’t Breathe. Cinej Cine. J. 2021, 9, 492–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauci, V.; Callus, A.M. Enabling Everything: Scale, Disability and the Film The Theory of Everything. Disabil. Soc. 2015, 30, 1282–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lopera-Mármol, M.; Jiménez-Morales, M.; Jiménez-Morales, M. Narrative Representation of Depression, ASD, and ASPD in «Atypical», «My Mad Fat Diary» and «The End of The F***ing World». Commun. Soc. 2023, 36, 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planella Ribera, J.; Pallarès Piquer, M.; Chiva Bartoll, Ó.; Muñoz Escalada, M.C. La visión de la discapacidad a través del cine. La película Campeones como estudio de caso [The Vision of Disability through Cinema. The Campeones Film as a Case Study]. Encuentros Maracaibo 2021, 13, 11–18. [Google Scholar]

- Santana Quintana, M.d.P. Impossible Paradise: Sex and Functional Diversity in Oasis (Oasiseu, 2002). Anclajes 2019, 23, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roshini, R.; Rajasekaran, V. An Analysis of Disability in The Little Mermaid: Examining Disparities and Similarities in the Fairytale and Its Movie Adaptation. Stud. Media Commun. 2023, 11, 220–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, R.E. Azeem and the Witch: Race, Disability, and Medievalisms in Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves. Open Libr. Humanit. 2023, 9, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S. Portrayal of Disability in Hindi Cinema. Int. J. Multidiscip. Res. 2024, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaptsi, A.; Vera Moreno, B.; Garrido, R. Análisis Psicosocial de La Representación Televisiva de La Diversidad Funcional Como Estrategia de Alfabetización Mediática. Ámbitos Rev. Int. Comun. 2024, 65, 32–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martos Contreras, E. The Treatment of Disability in El Cochecito (1960) | El tratamiento de la discapacidad en el cochecito (1960). Rev. Med. Cine 2024, 20, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ressa, T. Histrionics of Autism in the Media and the Dangers of False Balance and False Identity on Neurotypical Viewers. J. Disabil. Stud. Educ. 2021, 2, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aspler, J.; Harding, K.D.; Cascio, M.A. Representation Matters: Race, Gender, Class, and Intersectional Representations of Autistic and Disabled Characters on Television. Stud. Soc. Justice 2022, 16, 323–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García León, D.L. Body and Disability in Recent Colombian Cinema. The Case of Porfirio (2019) by Alejandro Landes | Cuerpo y Discapacidad En El Cine Colombiano Reciente. El Caso de Porfirio (2019) de Alejandro Landes. Bull. Hisp. Stud. 2021, 98, 507–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García León, D.L.; García León, J.E. Representing Male Disability in Colombian Audiovisual Media: The Masking of Social and Political Intersections in Los informantes. Lat. Am. Res. Rev. 2022, 57, 867–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang-Xu, S. The ambivalent vision: The “crip” invention of “blind vision” in blind massage. Int. J. Film Media Arts 2023, 8, 89–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biernoff, S. Sacha Polak’s Dirty God and the Politics of Authenticity. Cine. Cie 2022, 22, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tharian, P.R.; Henderson, S.; Wathanasin, N.; Hayden, N.; Chester, V.; Tromans, S. Characters with autism spectrum disorder in fiction: Where are the women and girls? Adv. Autism 2019, 5, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coronel-Hidalgo, J.; Cevallos-Solorzano, G.; Torres-Galarza, A.; Bailón-Moscoso, N. Down Syndrome Cinematography Analysis | Análisis de La Cinematografía Del Síndrome de Down. Educ. Medica 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, M.; Nordahl-Hansen, A. A Review of Research Studying Film and Television Representations of ASD. Rev. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2022, 9, 470–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendivelso Leal, R.; Hoyos Cuartas, L.A. Las Representaciones Sociales En La Discapacidad a Partir de La Cinematografía Infantil. Rev. Fac. Cienc. Salud UDES 2016, 3, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopera-Mármol, M.; Jiménez-Morales, M.; Jiménez-Morales, M. Communicating Health: Depictions of Depression, Antisocial Personality Disorder, and Autism without Intellectual Disability in British and U.S. Coming-of-Age TV Series. Humanities 2022, 11, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohlmann, A.; Harrison, M. To Be Continued: Serial Narration, Chronic Disease, and Disability. Lit. Med. 2019, 37, 67–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domaradzki, J. Treating Rare Diseases with the Cinema: Can Popular Movies Enhance Public Understanding of Rare Diseases? Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2022, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejías Martínez, G.; Mangado Martínez, M. La tartamudez en el cine: Análisis textual del cambio de paradigma en su representación [Stuttering in Cinema: Textual Analysis of the Paradigm Shift in Its Representation]. Fonseca J. Commun. 2022, 53–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, P. Nuances of the Unique and Evolving Conceptualisation of Intellectual Disability in India: A Study of the Changing Artistic Parlance of Representing Intellectually Disabled People in Mainstream Hindi Cinema. Br. J. Learn. Disabil. 2022, 50, 166–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter-Long, L. Disability cinema’s next wave: Observational agency subverts the ableist gaze. Film Q. 2022, 76, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz-Simón, L. The Construction of Characters with Disabilities in Film: The Importance of Verbal and Non-Verbal Communication. Vis. Rev. Int. Vis. Cult. Rev. Rev. Int. Cult. 2022, 11, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, R.; Gupta, K. From Representation to Re-Presentation: A Study of Disability in Literature and Cinema. Int. J. Innov. Multidiscip. Res. 2022, 5, 89–96. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins, C. Adaptation, Parody, and Disabled Masculinity in Motherless Brooklyn. Humanit. Switz. 2023, 12, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A. Representation of Disability-A Space of One’s Own in Literature and Cinema. Lapis Lazuli Int. Lit. J. 2022, 12, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Alkayed, Z.S.; Kitishat, A.R. Language Teaching for Specific Purposes: A Case Study of the Degree of Accuracy in Describing the Character of Mental Disabilities in Modern Arabic Drama (Egyptian Film Toot-Toot as an Example). J. Lang. Teach. Res. 2021, 12, 1039–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Zoubi, S.M.; Al-Zoubi, S.M. The Portrayal of Persons with Disabilities in Arabic Drama: A Literature Review. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2022, 125, 104221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).