Adaptation, Cross-Cultural Validation and Assessment of Measurement Properties of the French-Canadian Version of the Knowledge, Comfort, Approach and Attitude Towards Sexuality Scale (KCAASS) for Use in Stroke Rehabilitation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Population

2.3. Sampling and Recruitment

2.4. The Original KCAASS

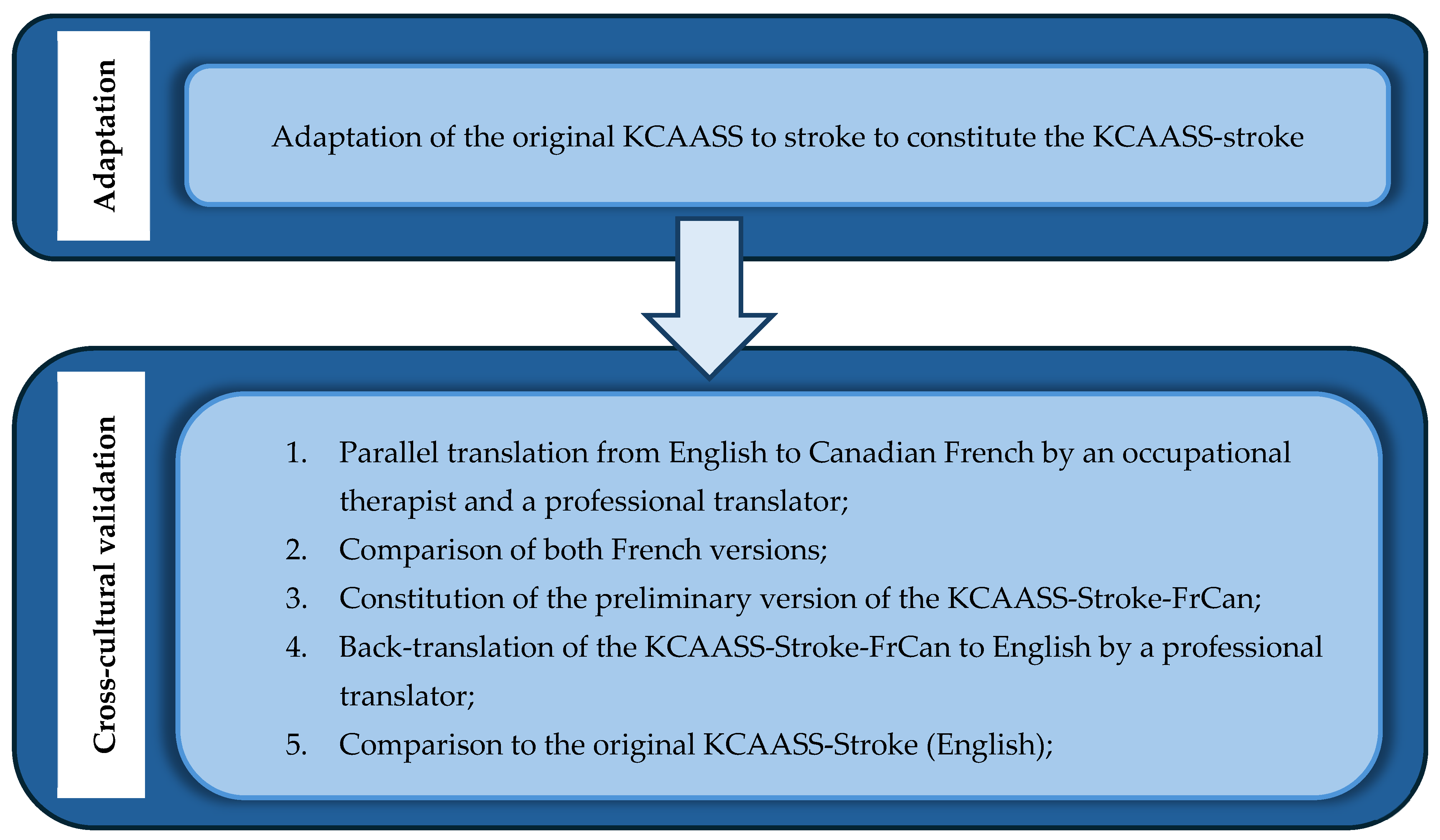

2.5. Adaptation and Cross-Cultural Validation

2.6. Measurement Properties the KCAASS-Stroke-FrCan

2.6.1. Data Collection

2.6.2. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Adaptation and Cross-Cultural Validation of the KCAASS-Stroke-FrCan

3.2. Measurement Properties the KCAASS-Stroke-FrCan

3.2.1. Sample Description

3.2.2. Construct Validity

3.2.3. Internal Consistency

3.2.4. Test—Retest Reliability

3.2.5. Standard Error of Measurement and Minimal Detectable Change

4. Discussion

4.1. Adaptation and Cross-Cultural Validation

4.2. Measurement Properties of the KCAASS-Stroke-FrCan

4.2.1. Construct Validity and Internal Consistency

4.2.2. Test–Retest Reliability

4.2.3. Responsiveness

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Disability Language/Terminology Positionality Statement

Abbreviations

| KCAASS | Knowledge, Comfort, Approach and Attitude towards Sexuality Scale |

| KCAASS-Stroke-FrCan | Knowledge, Comfort, Approach and Attitude towards Sexuality Scale adapted to Stroke and translated in Canadian French |

| ICC | Intraclass correlation coefficients |

| SEM | Standard error of measurement |

| MDC | Minimal detectable change |

References

- Feigin, V.L.; Stark, B.A.; Johnson, C.O.; Roth, G.A.; Bisignano, C.; Abady, G.G.; Abbasifard, M.; Abbasi-Kangevari, M.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abedi, V.; et al. Global, regional, and national burden of stroke and its risk factors, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Neurol. 2021, 20, 795–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Canadian Chronic Disease Surveillance System (CCDSS) [Data Tool]. 2025. Available online: https://health-infobase.canada.ca/ccdss/data-tool/ (accessed on 5 July 2025).

- Engel-Yeger, B.; Tse, T.; Josman, N.; Baum, C.; Carey, L.M. Scoping review: The trajectory of recovery of participation outcomes following stroke. Behav. Neurol. 2018, 2018, 5472018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grenier-Genest, A.; Gérard, M.; Courtois, F. Stroke and sexual functioning: A literature review. NeuroRehabilitation 2017, 41, 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korpelainen, J.T.; Nieminen, P.; Myllylä, V.V. Sexual functioning among stroke patients and their spouses. Stroke 1999, 30, 715–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H.; Kim, O. Influence of mastery and sexual frequency on depression in Korean men after a stroke. J. Psychosom. Res. 2008, 65, 565–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, M.; Lever, S.; McCluskey, A.; Power, E. How is sexuality after stroke experienced by stroke survivors and partners of stroke survivors? A systematic review of qualitative studies. Clin. Rehabil. 2019, 33, 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, M.; Low, M.A.; Power, E.; McCluskey, A.; Lever, S. Addressing Sexuality Among People Living With Chronic Disease and Disability: A Systematic Mixed Methods Review of Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices of Health Care Professionals. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2021, 102, 999–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auger, L.-P.; Pituch, E.; Filiatrault, J.; Courtois, F.; Rochette, A. Implementation of a sexuality interview guide in stroke rehabilitation: A feasibility study. Disabil. Rehabil. 2021, 9, 4014–4022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, K.; Dodington, A.; Smith, C.; Heck, C.S. Addressing clients’ sexual health in occupational therapy practice. Can. J. Occup. Ther. 2020, 87, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kendall, M.; Booth, S.; Fronek, P.; Miller, D.; Geraghty, T. The development of a scale to assess the training needs of professionals in providing sexuality rehabilitation following spinal cord injury. Sex. Disabil. 2003, 21, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fronek, P.; Kendall, M.; Booth, S.; Eugarde, E.; Geraghty, T. A longitudinal study of sexuality training for the interdisciplinary rehabilitation team. Sex. Disabil. 2011, 29, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazukauskas, K.A.; Lam, C.S. Disability and Sexuality: Knowledge, Attitudes, and Level of Comfort Among Certified Rehabilitation Counselors. Rehabil. Couns. Bull. 2010, 54, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, M.A.; Power, E.; McGrath, M. Sexuality after stroke: Exploring knowledge, attitudes, comfort and behaviours of rehabilitation professionals. Ann. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2022, 65, 101547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, M.W.M.; Gianotten, W.L.; Heijnen, L.; Lambers, E.J.H.R.; Willems, M. Sexological Competence of Different Rehabilitation Disciplines and Effects of a Discipline-specific Sexological Training. Sex. Disabil. 2008, 26, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samain, J.; Courtois, F.; Moyson, J.; Stoquart, G.; Jacquemin, G. Traduction française et validation du questionnaire «Knowledge, Comfort, Approach and Attitudes Towards Sexuality Scale». Sexologies 2022, 31, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verschuren, J.E.A.; Enzlin, P.; Geertzen, J.H.B.; Dijkstra, P.U.; Dekker, R. Sexuality in people with a lower limb amputation: A topic too hot to handle? Disabil. Rehabil. 2013, 35, 1698–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianotten, W.L.; Bender, J.L.; Post, M.W.; Höing, M. Training in sexology for medical and paramedical professionals: A model for the rehabilitation setting. Sex. Relatsh. Ther. 2006, 21, 303–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonjon, G.; Ilharreborde, B.; Odent, T.; Moreau, S.; Glorion, C.; Mazda, K. Reliability and Validity of the French-Canadian Version of the Scoliosis Research Society 22 Questionnaire in France. Spine 2014, 39, E26–E34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbière, M.; Fraccaroli, F. La conception, la validation, la traduction et al. l’adaptation transculturelle d’outils de mesure: Exemples dans le domaine de la santé mentale. In Méthodes Qualitatives, Quantitatives et Mixtes, 2nd ed.; Corbière, M., Larivière, N., Eds.; Presses de l’Université du Québec (PUQ): Québec City, QC, Canada, 2020; pp. 703–752. [Google Scholar]

- Mundfrom, D.J.; Shaw, D.G.; Ke, T.L. Minimum sample size recommendations for conducting factor analyses. Int. J. Test. 2005, 5, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, K. Unravelling factor analysis. Evid. Based Ment. Health 2008, 11, 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavakol, M.; Dennick, R. Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. Int. J. Med. Educ. 2011, 2, 53–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVellis, R.F.; Thorpe, C.T. Scale Development: Theory and Applications; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Weir, J.P. Quantifying test-retest reliability using the intraclass correlation coefficient and the SEM. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2005, 19, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Beckerman Vogelaar, T.W.; Lankhorst, G.J.; Verbeek, A.L. A criterion for stability of the motor function of the lower extremity in stroke patients using the Fugl-Meyer Assessment Scale. Scand. J. Rehabil. Med. 1996, 28, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassere, M.N.; van der Heijde, D.; Johnson, K.; Bruynesteyn, K.; Molenaar, E.; Boonen, A.; Verhoeven, A.; Emery, P.; Boers, M. Robustness and generalizability of smallest detectable difference in radiological progression. J. Rheumatol. 2001, 28, 911–913. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kazmers, N.H.; Hung, M.; Bounsanga, J.; Voss, M.W.; Howenstein, A.; Tyser, A.R. Minimal Clinically Important Difference After Carpal Tunnel Release Using the PROMIS Platform. J. Hand Surg. Am. 2019, 44, 947–953.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Buuren, S.; Groothuis-Oudshoorn, K. mice: Multivariate Imputation by Chained Equations in R. J. Stat. Softw. 2011, 45, 1–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanc, M. French in Canada. In Martinie Bruno. Carol Sanders (dir.), (1993), French Today. Language in Its Social Context; Linx: Singapore, 1995; Volume 33, pp. 160–165. [Google Scholar]

- Vinay, J.-P.; Darbelnet, J. Comparative Stylistics of French and English; John Benjamins Publishing Company: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Fronek, P.; Booth, S.; Kendall, M.; Miller, D.; Geraghty, T. The effectiveness of a sexuality training program for the interdisciplinary spinal cord injury rehabilitation team. Sex. Disabil. 2005, 23, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyer, K.; das Nair, R. Why don’t healthcare professionals talk about sex? A systematic review of recent qualitative studies conducted in the United Kingdom. J. Sex. Med. 2013, 10, 2658–2670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mean (SD)/Frequency (%) | |

|---|---|

| Age (Mean (SD)) | 39.01 (9.28) |

| Gender | |

| - Female | 185 (93%) |

| - Male | 13 (6.5%) |

| - Unspecified | 1 (0.5%) |

| Years of experience in stroke healthcare (Mean (SD)) | 9.37 (7.8%) |

| Profession Frequency (%) | |

| - Occupational therapist | 58 (29.1%) |

| - Physical therapist | 44 (22.1%) |

| - Speech language pathologist | 24 (12.1%) |

| - Nurse | 18 (9%) |

| - Psychologist and neuropsychologist | 14 (7%) |

| - Special education technician | 13 (6.5%) |

| - Social worker | 11 (5.5%) |

| - Physician | 6 (3%) |

| - Clinical coordinator | 4 (2%) |

| - Attendants (Orderlies) | 2 (1%) |

| - Dietitian | 2 (1%) |

| - Technologist in physical therapy | 2 (1%) |

| - Kinesiologist | 1 (0.5%) |

| Workplace (Frequency (%)) | |

| Quebec | 194 (97.5%) |

| - Site 1—Suburban | 52 (26.1%) |

| - Site 2—Urban | 44 (22.1%) |

| - Site 3—Urban | 20 (10%) |

| - Site 4—Urban | 16 (8%) |

| - Site 5—Urban | 14 (7%) |

| - Site 6—Urban | 12 (6%) |

| - Site 7—Rural | 10 (5%) |

| - Other | 26 (13%) |

| Ontario | 5 (2.5%) |

| Stroke healthcare context (Frequency (%)) | |

| - Acute | 11 (5.5%) |

| - Inpatient | 94 (47.2%) |

| - Early supported discharge | 4 (2%) |

| - Outpatient/Social reintegration | 79 (39.7%) |

| - Home-based services | 11 (5.5%) |

| KCAASS-Stroke-FrCan (Mean (SD)) | |

| - Knowledge (14–56) | 30.4 (5.3) |

| - Comfort (21–84) | 59.5 (15.3) |

| - Approach (5–20) | 8.8 (3.3) |

| - Attitude (5–20) | 18.3 (1.5) |

| - Total (45–160) | 117.0 (19.9) |

| KCAASS-Stroke-FrCan Subscale (Range) | Time 1 (Mean (SD)) | Time 2 (Mean (SD)) | ICC Between Times 1 and 2 (p) | SEM | MDC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge (14–56) | 29.7 (5.0) | 29.1 (5.1) | 0.69 (<0.001) | 2.2 | 6.2 |

| Comfort (21–84) | 59.4 (17.1) | 60.5 (14.8) | 0.74 (<0.001) | 5.8 | 16.2 |

| Approach (5–20) | 9.4 (3.6) | 10.0 (3.8) | 0.82 (<0.001) | 0.94 | 2.6 |

| Attitude (5–20) | 18.5 (1.6) | 18.6 (1.4) | 0.37 (0.003) | 1.33 | 3.7 |

| Total | 116.9 (21.5) | 118.2 (19.8) | 0.81 (<0.001) | 5.6 | 15.5 |

| Tested Models | Initial Values | Percentage of Variance | Cumulated Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| One-factor | 14.594 | 32.431 | 32.431 |

| Two-factor | 3.800 | 8.445 | 40.876 |

| Three-factor | 3.182 | 7.071 | 47.947 |

| Four-factor | 2.642 | 5.871 | 53.818 |

| KCAASS-Stroke-FrCan Items | F1 (Comfort) | F2 (Knowledge) | F3 (Approach) | F4 (Attitude) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Anatomy | 0.184 | 0.578 | 0.155 | 0.102 |

| 2. Positioning | 0.198 | 0.534 | 0.241 | 0.141 |

| 3. Bladder/bowel | 0.169 | 0.454 | 0.133 | −0.075 |

| 4. Devices | 0.274 | 0.436 | 0.070 | −0.092 |

| 5. Fertility | 0.246 | 0.399 | 0.011 | 0.005 |

| 6. Contraception | 0.236 | 0.441 | 0.210 | 0.045 |

| 7. Teenage issues | 0.411 | 0.486 | 0.087 | −0.060 |

| 8. Sexual preference | 0.345 | 0.616 | 0.121 | −0.028 |

| 9. Identity | 0.437 * | 0.319 | 0.225 | 0.067 |

| 10. Dating | 0.323 | 0.575 | 0.188 | 0.026 |

| 11. Communication | 0.334 * | 0.331 | 0.132 | −0.040 |

| 12. Inappropriate acts | 0.297 | 0.464 | −0.041 | 0.027 |

| 13. Counseling | 0.369 | 0.532 | 0.038 | −0.006 |

| 14. Professional issues | 0.238 | 0.380 | 0.049 | 0.039 |

| 15. Patient erection | 0.683 | −0.098 | −0.147 | 0.020 |

| 16. Loss | 0.448 | 0.160 | −0.523 * | 0.303 |

| 17. Ability to erect | 0.773 | −0.192 | 0.029 | 0.035 |

| 18. Ability for sex | 0.830 | −0.200 | 0.057 | −0.080 |

| 19. Orgasm | 0.866 | −0.195 | 0.081 | −0.040 |

| 20. Children | 0.742 | −0.177 | 0.097 | −0.203 |

| 21. Catheter | 0.750 | −0.239 | 0.146 | −0.090 |

| 22. Bowel | 0.854 | −0.162 | 0.157 | −0.077 |

| 23. Partner pain | 0.789 | −0.146 | 0.059 | −0.062 |

| 24. Dryness | 0.817 | −0.103 | 0.100 | −0.087 |

| 25. Positions | 0.649 | −0.188 | −0.004 | −0.048 |

| 26. Attractiveness | 0.781 | −0.146 | 0.111 | 0.026 |

| 27. Curiosity | 0.758 | 0.090 | 0.173 | −0.018 |

| 28. Attitude | 0.785 | −0.140 | 0.025 | −0.074 |

| 29. Preference | 0.725 | −0.169 | 0.105 | −0.094 |

| 30. Pornography | 0.594 | −0.007 | −0.387 | 0.118 |

| 31. Pleasure | 0.851 | −0.133 | 0.090 | −0.004 |

| 32. Body image | 0.856 | −0.149 | 0.123 | −0.002 |

| 33. Feeling | 0.833 | −0.080 | 0.085 | −0.074 |

| 34. Interest | 0.809 | −0.072 | 0.114 | −0.014 |

| 35. Arousal | 0.799 | −0.131 | 0.146 | −0.015 |

| 36. Masturbation | 0.483 | 0.112 | −0.529 | 0.277 |

| 37. Sexual acts | 0.468 | 0.127 | −0.579 | 0.353 |

| 38. Personal date | 0.438 | 0.016 | −0.518 | 0.274 |

| 39. Touching | 0.275 | 0.207 | −0.656 | 0.167 |

| 40. Personal approach | 0.335 | −0.006 | −0.676 | 0.128 |

| 41. Dismissal | −0.124 | −0.152 | 0.238 | 0.690 |

| 42. Partners | 0.112 | 0.061 | 0.082 | 0.225 |

| 43. Attractiveness | 0.065 | −0.137 | 0.445 | 0.662 |

| 44. Arousal | −0.002 | −0.118 | 0.346 | 0.795 |

| 45. Children | −0.061 | −0.172 | 0.367 | 0.654 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Auger, L.-P.; Quintal, I.; Goulet, K.; Miron, M.; La Charité-Harbec, S.; Rochette, A.; Higgins, J. Adaptation, Cross-Cultural Validation and Assessment of Measurement Properties of the French-Canadian Version of the Knowledge, Comfort, Approach and Attitude Towards Sexuality Scale (KCAASS) for Use in Stroke Rehabilitation. Disabilities 2025, 5, 106. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities5040106

Auger L-P, Quintal I, Goulet K, Miron M, La Charité-Harbec S, Rochette A, Higgins J. Adaptation, Cross-Cultural Validation and Assessment of Measurement Properties of the French-Canadian Version of the Knowledge, Comfort, Approach and Attitude Towards Sexuality Scale (KCAASS) for Use in Stroke Rehabilitation. Disabilities. 2025; 5(4):106. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities5040106

Chicago/Turabian StyleAuger, Louis-Pierre, Isabelle Quintal, Katia Goulet, Mirabelle Miron, Simon La Charité-Harbec, Annie Rochette, and Johanne Higgins. 2025. "Adaptation, Cross-Cultural Validation and Assessment of Measurement Properties of the French-Canadian Version of the Knowledge, Comfort, Approach and Attitude Towards Sexuality Scale (KCAASS) for Use in Stroke Rehabilitation" Disabilities 5, no. 4: 106. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities5040106

APA StyleAuger, L.-P., Quintal, I., Goulet, K., Miron, M., La Charité-Harbec, S., Rochette, A., & Higgins, J. (2025). Adaptation, Cross-Cultural Validation and Assessment of Measurement Properties of the French-Canadian Version of the Knowledge, Comfort, Approach and Attitude Towards Sexuality Scale (KCAASS) for Use in Stroke Rehabilitation. Disabilities, 5(4), 106. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities5040106