Public Transport in the Disabling City: A Narrative Ethnography of Dilemmas and Strategies of People with Mobility Disabilities

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Quebec City, a Path under Construction towards Inclusion

1.1.1. Context of Accessibility and Portrait of People with Mobility Disabilities

1.1.2. RTC, the Public Transport Service Provider

1.2. Barriers to Public Transport Accessibility for People with Disabilities

1.3. Experiencing Mobility: Meanings, Practices, Relationships

1.4. This Study

Research Questions

- Social and Physical Factors: What role do public transport and social and physical factors play in the (im)mobility practices of PMDs?

- Practices and Strategies: What are the personal, social, and landscape physical conditions that influence these practices? How do these conditions interact in their mobility decision-making ecosystem?

- Meanings of Disability: What are the social representations of fixed-route public transport and paratransit services that fuel PMDs’ decisions and strategies to use one or the other service? How do these representations feed into PMDs’ identities, their meanings of disability, and their perceptions of social inclusion?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Narrative Ethnography and Mobility Research in Disability Situations

2.2. Data Gathering

The objective of NI is the reconstruction of the interviewee’s experience, according to his/her subjective system of values. The interviewee builds a story, a narrative, of her/his experience; these stories reconstruct the time and space of the interviewee’s everyday life, his/her orientations and his/her projects and strategies [70].

2.3. Research Design

3. Results

3.1. Participants and Design

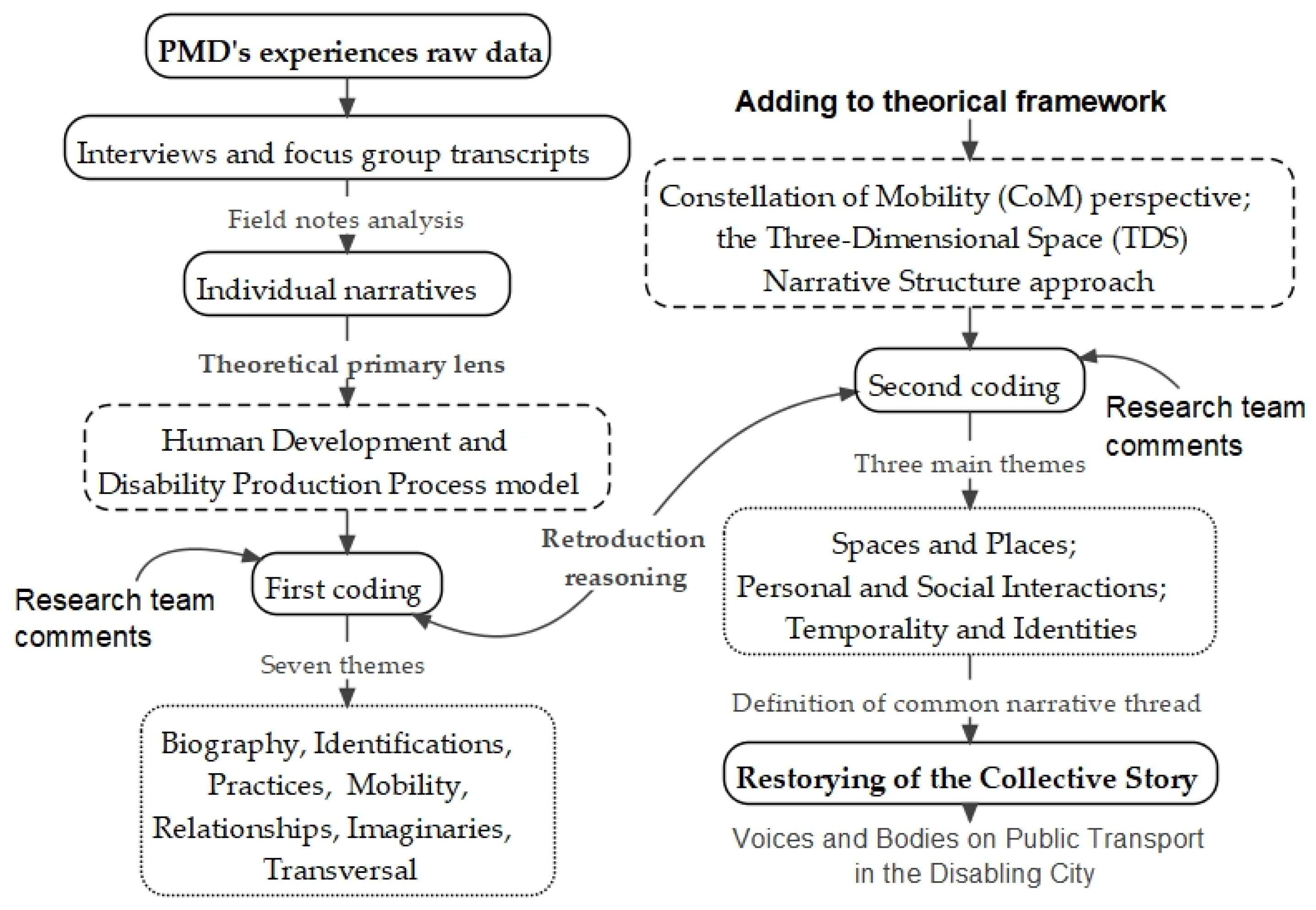

3.2. Analysis and Restorying Process of Mobility Experiences Data

3.3. Considerations Reading the Restorying Collective Story

3.4. Schematic Restorying of Collective Story

Voices and Bodies on Public Transport in the Disabled City

4. Discussion

4.1. Theoretical Dialogue: Narrating Disability in Constellations of Mobility

4.2. Dilemmas and Mobility Strategies of PMDs on Public Transport

4.2.1. Dilemma No. 1. A Necessary Choice: Fixed-Route Public Bus or Paratransit

4.2.2. Dilemma No. 2. Uncertainty or Freedom on the Fixed-Route Public Bus

50% of the RTC network’s total ridership is registered on the 13 accessible routes at the 430 accessible stops. 64% of all passenger boardings are made on the 13 accessible routes. Almost 80% of boardings and alightings on the 13 accessible routes are made at their accessible stops, again for all customers.

4.2.3. Dilemma No. 3. Spontaneity and Reliability in Paratransit

4.2.4. Dilemma No. 4. Ask, Ask, Ask, “I Don’t Want to Bother Anyone!”

4.2.5. Dilemma No. 5. Rhythms on the Fixed-Route Public Bus: Between Reliability and Inclusion

4.3. Limitations

4.4. Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. The Fixed-Route Public Bus: Before Boarding

The fixed-route public bus is safer than paratransit services, because we have our backs to the traffic, and behind us there is a cushion, which is this thick and bolted to the floor-ceiling. So, if there is an impact, we are pressed against the cushion. Yes, you can get hurt, but there is no danger of flying off again. Unlike the paratransit bus, where you’re facing traffic, and if there’s an impact and you’re badly strapped in, you’re pushed into the entrance.

For me, there are always questions before I go out. It’s always an adventure. It’s not saying, “Ah, I’m going to take the bus”, but “Can I take the bus?”. It’s not: “Do I want to?”, it’s: “Can I? Is the weather nice? Is the pavement not slippery? Is there a chance that I’ll find the empty space and be able to board? Will I be able to board and then get off at an accessible stop? So, there are many, many things I need to think about before getting out or considering taking the fixed-route public bus.

I’ve tried the bus, but it’s difficult because I have to be with someone all the time. I don’t have much balance, so when the bus pulls away, they’re in a hurry and then I understand, there’s another bus behind, another exchange somewhere. They start off and it’s often violent when they do. I need time to sit down and position mywalker.

For someone with physical disabilities, testing the fixed-route public bus in everyday life, when there are people at the stop, there are people on the bus, you know, the driver is in a hurry, it’s stressful. You say: “I don’t want to slow down the service. Maybe I won’t be able to”.

I’ve almost lost my physical capacity. It’s hard for me to go round the corner in my wheelchair. I already have a head control and a micro-joystick to drive my wheelchair. So, I’m really one of the most dependent users, if you like. I won’t be able to give the driver a ticket.

In winter, the pavements are in more or less good condition and people don’t like being frozen either, especially people with reduced mobility. So winter is the biggest factor. But there’s the snow clearance factor. It’s not just the cold, it’s the snow clearance. Often, you get to a resort and there are mountains of snow this high and all that. We can’t get to the bus station, and we get discouraged.

I have to take the climate into account. I can go out if it’s sunny. Then, when I’m stuck in the rain, well, where do I hide? I have to wait somewhere to catch a bus. And when you’re in a wheelchair, or with reduced mobility, an umbrella in the wind, when you don’t have enough muscles and all that, it’s the umbrella that’s in charge, not you. And when you’re in a wheelchair, like me, an umbrella is impossible. I can’t take an umbrella with the wind and all. And if I hold it low enough to be able to control it, I can’t see the road. So, it’s downright impossible.

At the same stop, sometimes a driver will deploy the bus’s access ramp. But the bus following, with another non-accessible route, will not deploy the access ramp, even if there is one. So, the disabled person will not be able to get on the bus, even if it is at an accessible stop and the entire bus is accessible, because it is not an accessible route.

Appendix A.2. Inside the Fixed-Route Public Bus

What I’ve observed is that, at the bus stop, the driver normally deploys the wheelchair access ramp, then the wheelchair user gets on, and then it’s the turn of the others, who have two legs. But often people pull over to get in front of the wheelchair user. The ramp isn’t even deployed and they practically jump over it.

People don’t realise. They think that with the wheelchair you move and then it will position itself, because there’s a sort of beam for safety, but you can’t go straight in, you need to position yourself first. And you’re like, “please, please, please, can you push yourself”. Then some of them push themselves, but just a little, and then you start to explain. That means you have to go forward, sideways, then backwards, so you need a good square of space.

Sometimes you have to ask the people who are already sitting in front to stand up, to fold their seats, to leave room so that we can get in, move back, and then tell them: “Okay, you can now lower the seats in front so that you can sit down”, but in a stop, you have to ask them to stand up.

It’s horrible, because you have to keep smiling, you know, there are people you’re going to say to: “Can you move?” and then they’re going to look at you like: “Bloody hell, I wasn’t expecting that, I’m reading, or I’m talking on the phone, you’re disturbing me, you can see it”. Then you say, “No, that’s not it, you’ll have to move again”. So, these are the things that stop you from taking the bus.

This has created tension among the drivers. I call it contradictory injunctions. On the one hand, customers want a fast, reliable service. They need to be able to make their connections. Then, at the same time, we tell them: “Take the time to deploy the ramp. Take the time to talk to someone who needs directions, to answer the question of someone with an intellectual limitation. But don’t start too quickly so that an elderly person has time to sit down”. But that creates tension. What’s more, as there aren’t that many wheelchair users on our buses, the drivers forget how to deploy the ramp, because they don’t deploy it very often.

Already with the negative perception that we have of disability, there are people who seem upset with a disabled person on the bus… That’s the price of disability. That’s what they make me do to find a seat with my wheelchair: beg, plead, ask, when it should be automatic that people see a wheelchair, they settle down, but no.

Let’s say I’m sitting on the bus and I’m in a bad mood for some reason, and then someone in a wheelchair asks for the ramp to be deployed, and then they get on the bus and slow down the bus journey. You know, I then look at the person in the wheelchair with my bad mood eyes, but because I’m in a bad mood for other things. I think people sometimes project, that it’s not always a look from someone who’s upset that the person is disabled.

We did a focus group with customers, people with intellectual disabilities, and they said they were being harassed on the bus. Then one person in a wheelchair said, “I’ve already used fixed-route public transport. I went back to STAC (paratransit services) because my life is complicated. My life is more difficult. I don’t want to get on the bus and have to face other people’s stares and attitudes, it’s too much. It’s just too much. That’s why I went back to STAC”.

Appendix A.3. Paratransit Services: Reasons, Rules, Possibilities

Paratransit has enabled people to become more autonomous, and there are people who also have a life because of it. There are people who started out with paratransit, then worked all their lives that way, thanks to paratransit. They couldn’t get a car, and you can’t just work for a few months in the summer, because in the winter you can’t go anywhere. Climate issues in Quebec mean that we really need a quality transport service, which is currently deteriorating.

Then, when it comes down to it, people say: “Yeah, that’s my right, ta ta ta”. Yes, but labour shortages, there are a whole bunch of factors that are uncontrollable, that will lead to a certain deterioration in the service, but it’s not necessarily because of the evil Government that planned everything. There’s no conspiracy to annoy the disabled.

STAC try to meet all the demand. But it’s not always possible, and then, as I said, they have taxi problems. So, they’re not able to meet all the demand. So, the first demands they meet are for healthcare, work and study. Then leisure, then shopping, that’s going to come later, there are choices to be made.

If people had their own vehicle, it would be a 15 or 20 min trip, but because they use paratransit, it’s an hour or an hour and a quarter trip, because they are picking up other users. Paratransit takes so long and is so restrictive that they just get off. We’d like to think about using active transport. If you have to go 2 kilometres, it’s conceivable, but if you’re 60 kilometres, no.

In the organisation of my life, in general, I alternate with teleworking, face-to-face work; there are days when I have to pick up my children from daycare, things like that. So, I have to do a lot of planning. And when you take paratransit, you always have to plan a day or two in advance, arrival time, departure time, all that. It’s hard to remember all these appointments and what time I have to be at what place. Whereas with the bus, you get out of your house, you know it’s coming every 15 min, you get out of your house, you take the bus when it comes, then you get off, then you don’t know what time your activity finishes.

Say a friend says: “Will you come to my house?”, I say: “OK. What time does it end?” Well, it ends when you’ve had enough. I can’t say that [laughs]. I have to leave at such and such a time, because I have transport. So, you have to plan ahead. And then, if you plan it like that, you come back at 9.00, and then, at 9.00, everybody’s gone, it’s over, and then you feel that your host would really like to go to bed, but now he’s waiting with you for half an hour, for you to take your transport to go home, or you yourself, you’re fed up, you’d like to go, but you can’t, your transport arrives in an hour. That’s what I find difficult about having a significant disability like that, is that you lose out on a lot of spontaneous opportunities. You know, someone calls you up and says, “Hey, Will, are you coming over to our place today? If they don’t give you a lift, and you don’t know the way by bus, you can’t go, because you would have had to know the day before, to plan your transport, to be able to go.

There are disabled people who want everything for free. But not me. I want a normal life. If I have the means to survive, then to pay for my things. I’m happy with that. To have a better income as a disabled person, to have the poverty line, let’s say, or the minimum guaranteed income. That’s a battle. But having privileges isn’t my battle either. If I want to be privileged because of my disability, I can make a face about it, if they want to give me privileges. That’s not what I want.

I used to take my car with someone who drove it, as a passenger. It was for grocery shopping, for pleasure parties, restaurants, outings. Then for work, it was paratransit. I don’t drive. I depend on friends. But I’ve started lending my car. For example, a friend will say to me: “You know what, there’s a disabled person who needs to go to the shopping centre and she needs to go to the restaurant. I’m going to invite her to go with me. Can I take your car?” Okay. So, I started lending her my car. My car was doing community work. [laughs]. One time, an attendant came and told me: there’s a lady who’d like to go to the Basilica of Sainte-Anne-de Beaupré, but the paratransit service won’t take her. But she’d like to go and say her prayers there. Can we take your car? Okay, go ahead. I’ve never seen this person before. I used to lend my car and I never got paid, but it could be a possibility for people who have adapted cars to help other disabled people, like a breakdown assistance community, carpooling between people. Because I say to myself: “My car is here”. It doesn’t move any more, it rots. I pay a lot more in repairs when it doesn’t move than I’m going to lose when people use it, you understand, even if they don’t pay me. And I think there are things that even among us, disabled people, some have the means, or that they can help others who don’t have the means, or to help them out. For example, someone who is caught in the middle of the night, then has something to do, then someone lends him the car, because there is something urgent to do, but the paratransit services is closed.

Even if you made the fixed-route public bus 100% accessible, there are still many who prefer paratransit. It’s door-to-door, some people don’t have a choice, but there are also a lot of people who feel that part of their social life, in any case, is the interaction they have on paratransit, whether it’s with a driver or with other customers.

We would never question paratransit. What we’re doing for accessible transport for fixed-route public buses isn’t about doing away with paratransit. That’s just not possible. But it’s very difficult, it’s a challenge, because people are used to paratransit, because it’s an accessible door-to-door service.

Appendix A.4. “We’re Stuck with Other People”—Paratransit Populations

I think the hidden aim, which is admitted but never talked about, is to allow older people to take public transport for longer so as not to overburden the paratransit system. To use paratransit, you have to have a medical diagnosis of permanent disability that prevents you from taking fixed-route public transport.

References

- Denault, M.; Varin, M.-A. La relance et l’électrification du transport en commun. Transp. Regards Mobilité Québec Sabl. 2023, 30, 55–57. [Google Scholar]

- Réseau de Transport de la Capitale (RTC). Améliorer l’Accessibilité du Transport en Commun Régulier à Québec, Bilan du Plan de Développement 2012–2016. 2012. Available online: https://cdn.rtcquebec.ca/sites/default/files/2019-07//Bilan_PlanDev%202012-2016_accessible.pdf (accessed on 7 October 2023).

- Boucher, N.; Dumont, I.; Fougeyrollas, P.; Beauregard, L.; Lachapelle, Y.; Gascon, H.; Caillouette, J. De manière singulière et d’usage inclusif. Représentations sociales, Transport collectif et interrelations entre handicap, territoire et environnement. Rech. Sociographiques 2019, 60, 139–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Chowdhury, S. Investigating the barriers in a typical journey by public transport users with disabilities. J. Transp. Health 2018, 10, 361–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, J. Self-Determination in Transportation: The Route to Social Inclusion for People with Disabilities. Ph.D. Thesis, City University of New York, New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Office at Geneva. Disability Inclusive Language Guidelines. United Nations Disability Inclusion Strategy; United Nations: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cass, N.; Shove, E.; Urry, J. Social Exclusion, Mobility and Access. Sociol. Rev. 2005, 53, 539–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, N.; Butz, D. Moving toward mobility justice. In Mobilities, Mobility Justice and Social Justice; Nancy, C., David, B., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; ISBN 978-0-429-43458-7. [Google Scholar]

- Fougeyrollas, P.; Boucher, N.; Fiset, D.; Grenier, Y.; Noreau, L.; Philibert, M.; Gascon, H.; Morales, E.; Charrier, F. Handicap, environnement, participation sociale et droits humains: Du concept d’accès à sa mesure. Dév. Hum. Handicap. Chang. Soc./Hum. Dev. Disabil. Soc. Change 2015, 5–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prince, M.J. Disabling Cities and Repositioning Social Work. In Social Work and the City: Urban Themes in 21st-Century Social Work; Williams, C., Ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2016; pp. 173–192. ISBN 978-1-137-51623-7. [Google Scholar]

- RTC Media. Le RTC s’Engage à Rendre 1000 Arrêts Accessibles d’Ici 2028. Communiqués 2022. Available online: https://www.rtcquebec.ca/medias/communiques/le-rtc-sengage-rendre-1-000-arrets-accessibles-dici-2028 (accessed on 7 October 2023).

- Réseau de Transport de la Capitale (RTC). Rapport d’Activité 2021. 2022. Available online: https://cdn.rtcquebec.ca/sites/default/files/2022-05/RTC_Rapport%20activite%202021.pdf (accessed on 7 October 2023).

- Statistics Canada. Canadian Survey on Disability, 2017: Concepts and Methods Guide. 2017. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/89-654-x/89-654-x2018001-eng.htm (accessed on 7 October 2023).

- Ministère des Transports, Gouvernement du Québec. Paratransit Eligibility Policy. 1998. Available online: https://cdn-contenu.quebec.ca/cdn-contenu/adm/min/transports/transports/transport_adapte/paratransit-eligibility-policy.pdf (accessed on 7 October 2023).

- Langan, C. Mobility Disability. Public. Cult. 2001, 13, 459–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velho, R.; Holloway, C.; Symonds, A.; Balmer, B. The Effect of Transport Accessibility on the Social Inclusion of Wheelchair Users: A Mixed Method Analysis. Soc. Incl. 2016, 4, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarhaug, J.; Elvebakk, B. The impact of Universally accessible public transport–a before and after study. Transp. Policy 2015, 44, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezyak, J.L.; Sabella, S.; Hammel, J.; McDonald, K.; Jones, R.A.; Barton, D. Community participation and public transportation barriers experienced by people with disabilities. Disabil. Rehabil. 2020, 42, 3275–3283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.; Esfahani, H.N.; Novack, V.L.; Sheen, J.; Hadayeghi, H.; Song, Z.; Christensen, K. Impacts of disability on daily travel behaviour: A systematic review. Transp. Rev. 2022, 43, 178–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kett, M.; Cole, E.; Turner, J. Disability, Mobility and Transport in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Thematic Review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larrouy, M. Invention of Accessibility: French Urban Public Transportation Accessibility from 1975 to 2006. Rev. Disabil. Stud. Int. J. 2006, 2, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Levine, J.; Grengs, J.; Merlin, L.A. The Special Case of Public-Transport Accessibility. In From Mobility to Accessibility: Transforming Urban Transportation and Land-Use Planning; Cornell University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2019; ISBN 978-1-5017-1610-2. [Google Scholar]

- Carlsson, G. Travelling by urban public transport: Exploration of usability problems in a travel chain perspective. Scand. J. Occup. Ther. 2004, 11, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavery, I.; Davey, S.; Woodside, A.; Ewart, K. The vital role of street design and management in reducing barriers to older peoples’ mobility. Landsc. Urban. Plan. 1996, 35, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petzäll, J. Traversing step obstacles with manual wheelchairs. Appl. Erg. 1996, 27, 327–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertocci, G.; Smalley, C.; Page, A.; Digiovine, C. Manual wheelchair propulsion on ramp slopes encountered when boarding public transit buses. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2019, 14, 561–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almada, J.F.; Renner, J.S. Public transport accessibility for wheelchair users: A perspective from macro-ergonomic design. Work 2015, 50, 531–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Souza, C.; Steinfeld, E.; Paquet, V.; Feathers, D. Space Requirements for Wheeled Mobility Devices in Public Transportation: An Analysis of Clear Floor Space Requirements: (Investing in Accessible Transportation and Mobility ABE60). Transp. Res. Rec. 2010, 2145, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazares, R.A. Disability Inclusive Transportation: Assessing First Mile Last Mile Conditions in the Richmond Region. Master of Urban and Regional Planning Capstone Projects. 2021. Available online: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1047&context=murp_capstone (accessed on 7 October 2023).

- D’Souza, C.; Paquet, V.; Lenker, J.A.; Steinfeld, E. Effects of transit bus interior configuration on performance of wheeled mobility users during simulated boarding and disembarking. Appl. Erg. 2017, 62, 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, K.L.; Bertocci, G.; Smalley, C. Ramp-related incidents involving wheeled mobility device users during transit bus boarding/alighting. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2015, 96, 928–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenker, J.; Damle, U.; D’Souza, C.; Paquet, V.; Mashtare, T.; Steinfeld, E. Usability Evaluation of Access Ramps in Transit Buses: Preliminary Findings. J. Public. Transp. 2016, 19, 109–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwangbo, H.; Kim, J.; Kim, S.; Ji, Y.G. Toward Universal Design in Public Transportation Systems: An Analysis of Low-Floor Bus Passenger Behavior with Video Observations. Hum. Factors Ergon. Manuf. Serv. Ind. 2015, 25, 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wretstrand, A.; Petzäll, J.; Ståhl, A. Safety as perceived by wheelchair-seated passengers in special transportation services. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2004, 36, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velho, R. Transport accessibility for wheelchair users: A qualitative analysis of inclusion and health. Int. J. Transp. Sci. Technol. 2019, 8, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egger, S.M.; Gemperli, A.; Filippo, M.; Liechti, R.; Gantschnig, B.E. The experiences and needs of persons with disabilities in using paratransit services. Disabil. Health J. 2022, 15, 101365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Routhier, F.; Lettre, J.; Pigeon, C.; Fiset, D.; Martel, V.; Binet, R.; Vézina, V.; Collomb d‘Eyrames, O.; Waygood, E.O.; Mostafavi, M.A.; et al. Evaluation of three pedestrian phasing with audible pedestrian signals configurations in Quebec City (Canada): An exploratory study of blind or visually impaired persons’ sense of safety, preferences, and expectations. Disabil. Rehabil. 2023, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin Ginis, K.A.; Sinden, A.R.; Bonaccio, S.; Labbé, D.; Guertin, C.; Gellatly, I.R.; Koch, L.; Ben Mortenson, W.; Routhier, F.; Basham, C.A.; et al. Experiential Aspects of Participation in Employment and Mobility for Adults with Physical Disabilities: Testing Cross-Sectional Models of Contextual Influences and Well-Being Outcomes. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2023, 105, 303–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, A.; O’Dea, E.; Bigonnesse, C.; Labbe, D.; Mahal, T.; Qureshi, M.; Mortenson, W.B. Stakeholders Walkability/Wheelability Audit in Neighbourhoods (SWAN): User-led audit and photographic documentation in Canada. Disabil. Soc. 2020, 35, 902–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, K.L.; Noreau, L.; Gagnon, M.-A.; Barthod, C.; Hitzig, S.L.; Routhier, F. Housing, Transportation and Quality of Life among People with Mobility Limitations: A Critical Review of Relationships and Issues Related to Access to Home- and Community-Based Services. Disabilities 2022, 2, 204–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Conference Board of Canada. The Business Case to Build Physically Accessible Environments; The Conference Board of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cresswell, T. Towards a Politics of Mobility. Environ. Plan. D 2010, 28, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cresswell, T. Geographies of Mobilities: Practices, Spaces, Subjects; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; ISBN 978-1-315-58439-3. [Google Scholar]

- Pelgrims, C. Tension between Fast and Slow Mobilities: Examining the Infrastructuring Processes in Brussels (1950–2019) through the Lens of Social Imaginaries. Transfers 2019, 9, 20–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansilla, J.C.; Mejía Betancur, L.; Queiroz Lambach, C. Transmedial Worlds with Social Impact: Exploring Intergenerational Learning in Collaborative Video Game Design. J. Child. Stud. 2019, 44, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansilla, J.C. Thinking society and cultural practices in the (digital) hybrid age: Notes and queries on Media Ecology Research. New Explor. Stud. Cult. Commun. 2021, 2, 93–108. Available online: https://jps.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/nexj/article/view/37373 (accessed on 7 October 2023).

- Sylvestre, G. Aging and sustainability: Creating a discourse on places of inclusive mobility for the promotion of longevity. In Diverse Perspectives on Aging in a Changing World; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; ISBN 978-1-315-63838-6. [Google Scholar]

- Mansilla, J.C.; Schwartz, G. Youth Culture and Digital Resistance: Paris, Medellín and São Paulo. In Survey on the Use of Information and Communication Technologies in Brazilian Cultural Facilities: ICT in Culture 2016; Regional Center for Studies on the Development of the Information Society—Cetic.br: São Paulo, Brazil, 2017; pp. 171–180. ISBN 978-85-5559-043-6. [Google Scholar]

- Morin, E. Introduction à la Pensée Complexe; ESF éditeur: Paris, France, 1990; ISBN 978-2-7101-0800-9. [Google Scholar]

- Comunian, R. Location, location, location: Exploring the complex relationship between creative industries and place. Creat. Ind. J. 2010, 3, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castells, M. Space of Flows, Space of Places: Materials for a Theory of Urbanism in the information age. In The Cybercities Reader; Graham, S., Ed.; The Routledge urban reader series; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2004; pp. 82–93. ISBN 978-0-415-27955-0. [Google Scholar]

- Appadurai, A. Global Ethnoscapes: Notes and Queries for a Transnational Anthropology. In Interventions: Anthropologies of the Present; School of American Research: Santa Fe, NM, USA, 1989; pp. 48–65. Available online: https://web.mit.edu/uricchio/Public/Documents/Appadurai-Modernity_at_Large-Ch3.pdf (accessed on 7 October 2023).

- Mannheim, K. The Problem of Generations. In Essays on the Sociology of Knowledge; Kecskemeti, P., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 1952; pp. 276–322. [Google Scholar]

- Schatzki, T.R. The Trajectories of a Life. In Doing Transitions in the Life Course: Processes and Practices; Stauber, B., Walther, A., Settersten, R.A., Jr., Eds.; Life Course Research and Social Policies; Springer International Publishing: Cham, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 19–34. ISBN 978-3-031-13512-5. [Google Scholar]

- Manzo, L.C.; Perkins, D.D. Finding Common Ground: The Importance of Place Attachment to Community Participation and Planning. J. Plan. Lit. 2006, 20, 335–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imrie, R. Disability and Discourses of Mobility and Movement. Environ. Plan. A 2000, 32, 1641–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boucher, N. Handicap, recherche et changement social. L’émergence du paradigme émancipatoire dans l’étude de l’exclusion sociale des personnes handicapées. Lien Soc. Polit. 2003, 50, 147–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fougeyrollas, P.; Boucher, N.; Edwards, G.; Grenier, Y.; Noreau, L. The Disability Creation Process Model: A Comprehensive Explanation of Disabling Situations as a Guide to Developing Policy and Service Programs. Scand. J. Disabil. Res. 2019, 21, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharebaghi, A.; Mostafavi, M.-A.; Chavoshi, S.H.; Edwards, G.; Fougeyrollas, P. The Role of Social Factors in the Accessibility of Urban Areas for People with Motor Disabilities. ISPRS Int. J. Geo Inf. 2018, 7, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffestin, C. Territorialité: Concept ou paradigme de la géographie sociale? Geogr. Helv. 1986, 41, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stafford, L.; Vanik, L.; Bates, L.K. Disability Justice and Urban Planning. Plan. Theory Pract. 2022, 23, 101–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clandinin, D.J. Engaging in Narrative Inquiry; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-1-315-42961-8. [Google Scholar]

- Squire, C. From Experience-Centred to Socioculturally-Oriented Approaches to Narrative. In Doing Narrative Research; SAGE Publications, Ltd.: New York, NY, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-1-5264-0227-1. [Google Scholar]

- Lamb, E.G. Age and/as Disability: A Call for Conversation. Age Cult. Humanit. Interdiscip. J. 2015, 2, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, M.; Bigby, C. (Eds.) Handbook on Ageing with Disability; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2021; ISBN 978-0-429-46535-2. [Google Scholar]

- Raymond, É.; Grenier, A.; Hanley, J. Community Participation of Older Adults with Disabilities. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2014, 24, 50–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, R. Participant pseudonyms in qualitative family research: A sociological and temporal note. Fam. Relatsh. Soc. 2020, 9, 383–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guenther, K.M. The politics of names: Rethinking the methodological and ethical significance of naming people, organizations, and places. Qual. Res. 2009, 9, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarbin, T.R. Narrative Psychology: The Storied Nature of Human Conduct; Bloomsbury Academic: New York, NY, USA, 1986; ISBN 978-0-275-92103-3. [Google Scholar]

- Feixa, C.; Sánchez-García, J.; Soler-i-Martí, R.; Ballesté, E.; Hansen, N. Methodology Handbook: Ethnography and Data Analysis; TRANSGANG Working Papers 4.1; Universitat Pompeu Fabra & European Research Council: Barcelona, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Russo, J. Anthropology in the Meantime: Experimental Ethnography, Theory, and Method for the Twenty-First Century by Michael, M. J. Fischer (review). Anthropol. Q. 2020, 93, 1655–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansilla, J.C.; Grassi, P.; Palmas, L.Q. Contemporary Youth Culture at the Margins of Marseille and Milan: Gangs, Music, and Global Imaginaries. Youth Glob. 2022, 3, 359–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez García, J.; Oliver, M.; Mansilla, J.C.; Hansen, N.; Feixa, C. Between cyberspace and the street: Conducting ethnography with youth street groups in times of physical distancing. Hipertext.net 2020, 21, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballesté, E.; Grassi, P.; Mansilla, J.C.; Oliver, M. Youth Street Groups and Mediation in Southern Europe: Ethnographic Findings; TRANSGANG Final Reports 01; Universitat Pompeu Fabra & European Research Council: Barcelona, Spain, 2023; p. 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cass, N.; Doughty, K.; Faulconbridge, J.; Murray, L. Ethnographies of Mobilities and Disruption; Research Report; Research Councils UK Energy Programme: Brighton, UK, 2015; p. 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grard, J. Approche(s) narrative(s) et récit à la première personne. Généalogie et politiques de l’enquête. Vie Soc. 2017, 20, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-1-4129-9531-3. [Google Scholar]

- Bruner, J. Life as Narrative. Soc. Res. 1987, 54, 11–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillen, F.; Elida, D. Investigación cualitativa: Método fenomenológico hermenéutico. Propósitos Represent. 2019, 7, 201–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.A.; Flowers, P.; Larkin, M. Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis: Theory, Method and Research, 2nd ed.; SAGE: London, UK, 2022; ISBN 978-1-5297-5380-6. [Google Scholar]

- Parks, P. Story Circles: A New Method of Narrative Research. AM J. Qual. Res. 2023, 7, 58–72. [Google Scholar]

- Polkinghorne, D.E. Validity Issues in Narrative Research. Qual. Inq. 2007, 13, 471–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovchelovitch, S.; Bauer, M.W. Narrative Interviewing. In Qualitative Researching with Text, IMAge and Sound: A Practical Handbook; Bauer, M.W., Gaskell, G., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2000; pp. 57–74. ISBN 978-0-7619-6481-0. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, D.L. Focus Groups as Qualitative Research; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1997; ISBN 978-1-4129-8428-7. [Google Scholar]

- Haw, K.; Hadfield, M. Video in Social Science Research Functions and Forms; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-0-203-83911-9. [Google Scholar]

- Tedlock, B. From Participant Observation to the Observation of Participation: The Emergence of Narrative Ethnography. J. Anthropol. Res. 1991, 47, 69–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragin, C.C. Constructing Social Research: The Unity and Diversity of Method; Pine Forge Press: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1994; ISBN 978-0-8039-9021-0. [Google Scholar]

- Ollerenshaw, J.A.; Creswell, J.W. Narrative Research: A Comparison of Two Restorying Data Analysis Approaches. Qual. Inq. 2002, 8, 329–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewey, J. Experience and Education, Reprint ed.; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1997; ISBN 978-0-684-83828-1. [Google Scholar]

- Connelly, F.M.; Clandinin, D.J. Narrative Inquiry; Routledge Handbooks Online: New York, NY, USA, 2006; ISBN 978-0-8058-5932-4. [Google Scholar]

- Clandinin, D.J.; Connelly, F.M. Narrative Inquiry: Experience and Story in Qualitative Research; Jossey-Bass Publishers: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Desmond, M. Relational ethnography. Theor. Soc. 2014, 43, 547–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, M. Quality indicators in narrative research. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2021, 18, 353–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, P.H. Assuring Quality in Narrative Analysis. West. J. Nurs. Res. 1996, 18, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, D.; Munger, F. Narrative, Disability, and Identity. Narrative 2007, 15, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sait, C. “This Journey Has Definitely Changed Me”: An Ethnographic Narrative Exploring Disabled Peoples’ Lives through Embodied Experiences and Identity Negotiation. Master’s Thesis, Te Herenga Waka-Victoria University of Wellington, Wellington, New Zealand, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, B.; Sparkes, A.C. Narrative and its potential contribution to disability studies. Disabil. Soc. 2008, 23, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tindall, L.; Smith, J.A.; Flower, P.; Larkin Interpretative, M. Phenomenological Analysis: Theory, Method and Research. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2009, 6, 346–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, D. Narrative ethnography: How to study stories in the context of their telling. In Handbook of Ethnography in Healthcare Research; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2020; ISBN 978-0-429-32092-7. [Google Scholar]

- Shakespeare, T. The Social Model of Disability. In The Disability Studies Reader; Davis, L.J., Ed.; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2006; pp. 2–197. [Google Scholar]

- Chaves, E.S.; Cooper, R.A.; Collins, D.M.; Karmarkar, A.; Cooper, R. Review of the use of physical restraints and lap belts with wheelchair users. Assist. Technol. 2007, 19, 94–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pyer, M.; Tucker, F. ‘With us, we, like, physically can’t’: Transport, mobility and the leisure experiences of teenage wheelchair users. Mobilities 2014, 12, 36–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Souza, C.; Paquet, V.L.; Lenker, J.A.; Steinfeld, E. Self-Reported Difficulty and Preferences of Wheeled Mobility Device Users for Simulated Low-Floor Bus Boarding, Interior Circulation, and Disembarking. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2019, 14, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Best, K.; Kiki, M.; Lamontagne, M.E.; Routhier, F. Public transportation training: A low-tech approach to facilitate using the bus for people with disabilities. In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference of the Association for the Advancement of Assistive Technology in Europe (AAATE), Paris, France, 30 August–1 September 2023; pp. 209–211. [Google Scholar]

- Ministère des Transports du Québec; Réseau de Transport de la Capitale; Société de Transport de Lévis; Communauté Métropolitaine de Québec; Ville de Québec; Ville de Lévis. EOD2017, Enquête Origine-Destination, Région Québec-Lévis: La Mobilité des Personnes dans la Région de Québec-Lévis. Volet Enquête-Ménages. Sommaire des Résultats. 2019. Available online: https://www.transports.gouv.qc.ca/fr/ministere/Planification-transports/enquetes-origine-destination/quebec/2017/Documents/EOD17_faits_saillants_VF.pdf (accessed on 7 October 2023).

- Ripat, J.D.; Brown, C.L.; Ethans, K.D. Barriers to wheelchair use in the winter. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2015, 96, 1117–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abma, T.A.; Stake, R.E. Science of the Particular: An Advocacy of Naturalistic Case Study in Health Research. Qual. Health Res. 2014, 24, 1150–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, L.; Doughty, K. Interdependent, imagined, and embodied mobilities in mobile social space: Disruptions in ‘normality’, ‘habit’ and ‘routine’. J. Transp. Geogr. 2016, 55, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, H. Rhythmanalysis: Space, Time and Everyday Life; Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK, 2013; ISBN 978-1-4725-2886-5. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-Determination Theory: Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development, and Wellness; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-1-4625-2880-6. [Google Scholar]

- Bibri, S.E.; Krogstie, J.; Kärrholm, M. Compact city planning and development: Emerging practices and strategies for achieving the goals of sustainability. Dev. Built Environ. 2020, 4, 100021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Duren, N.R.L.; Salazar, J.P.; Duryea, S.; Mastellaro, C.; Freeman, L.; Pedraza, L.; Porcel, M.R.; Sandoval, D.; Aguerre, J.A.; Angius, C.; et al. Cities as Spaces for Opportunities for All: Building Public Spaces for People with Disabilities, Children and Elders; Inter-American Development Bank (IDB): Washington DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Situation * (Place/Space CoM) | Continuity * (MovementCoM) | Interaction * | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Past * | Present * | Future * | Personal * (Practice CoM) | Social * (Representation CoM) | |

| Look at context, time, and place situated in a physical landscape or setting with topological and spatial boundaries with characters’ intentions, purposes, and different points of view (TDS). | Look back to remembered experiences, feelings, and stories from earlier times (TDS). | Look at current experiences, feelings, and stories relating to actions of an event (TDS). | Look forward to implied and possible experiences and plot lines (TDS). | Look inward to internal conditions, feelings, hopes, aesthetic reactions, and moral dispositions (TDS). | Look outward to existential conditions in the environment with other people and their intentions, purposes, assumptions, and points of view (TDS). |

| Boundaries of a physical landscape. Movement needs infrastructural context (spaces) in which mobility is enacted. Our mobilities create spaces and stories—spatial stories. Space, place, and landscape are ‘verbs’ rather than ‘nouns’ (CoM). | Patterns of movement that are embedded in time and informed by memories, events, and expectations (CoM). Research on human experiences of mobility is concerned with the evolution of events (movements) that occur over time, and with the way in which personal memories and expectations, social representations, infrastructural context, and interactions are articulated in narratives that generate spaces and places of human action (TDS linked to CoM). | Ways of practicing movement that make sense for each person. Practices are associated with different spaces, scales, ranges of embodied engagements, technologies, and infrastructure (CoM). | Social representations of the movement and people’s identities, and the conflicts between peripheral (resistance) and central (hegemonic) narratives (CoM). | ||

| People with Mobility Disabilities (PMD) | Stakeholders Involved in Inclusive Mobility (STKs) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pseudonym | Age | Gender 1 | Impairment | Aids | Pseudonym | Age | Gender 1 | Organisation (Field of Action) |

| Amber * | 30s | Woman | Visual | White Cane | Ellen | 30s | Woman | Adaptavie (rehabilitation services) |

| Tom * | 40s | Man | Motor | Manual Wheelchair | ||||

| Gregory * | 50s | Man | Motor | Orthopaedic Shoes | Rachel | 50s | Woman | RTC (fixed-route and paratransit transport provider) |

| Philbert * | 60s | Man | Motor | Electric Wheelchair | ||||

| Kenneth * | 50s | Man | Motor | Rollator | Gina | 40s | Woman | Ville de Québec (Transport Mobility Government Section) |

| Lizzie * | 60s | Woman | Motor | Electric Wheelchair | ||||

| Camelia * | 50s | Woman | Motor | Electric Wheelchair | Basil | 50s | Man | Capvish (civil society organisation for PMD) |

| Rowan | 30s | Man | Motor | Electric Wheelchair | ||||

| Ernest * | 50s | Man | Motor | Manual Wheelchair | ||||

| Wilbur | 50s | Man | Visual | Guide Dog | ||||

| Henry | 70s | Man | Motor | Electric Wheelchair | ||||

| Sarah * | 60s | Woman | Motor | Rollator | ||||

| Situation (Place/Space) | Continuity (Movement) | Interaction | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Past | Present | Future | Personal (Practice) | Social (Representation) | |

| People with mobility disabilities in Quebec City experiencing public transport. The accessibility of Quebec City’s physical landscape depends on an intricate network of public governance. | “There are no more than 100 wheelchair users using fixed-route public buses, this is nothing” (Ernest). “The closer you are to the city centre, the easier it is to get moving. Because fixed-route transit or even paratransit can’t take you outside the city” (Ellen). | “I hope the tramway in Quebec City won’t be like that, because they talk about universal accessibility, but who knows what universal accessibility is?” (Wilbur). | “In Quebec City people think that public transport is for the poor, and soon they’ll be saying that it’s for disabled people” (Rachel). “There’s another group representing seniors, who have accessibility needs as they get older. I don’t want to say anything, but they’re all former public service retirees with large pension funds. They don’t want better bus access, they want parking” (Wilbur). | ||

| BEFORE BOARDING THE FIXED-ROUTE PUBLIC BUS With RTC’s integrated mobility support service—SAMI program, “customers” can test the accessibility of the buses (Rachel) | “When I fell out of the wheelchair on a snowy street, I fractured my wrist twice, I was left with a trauma” (Camelia). For wheelchair users, rainy days pose challenges for “finding shelter and use an umbrella while waiting for a bus” (Camelia). | “Is the weather nice? Is the pavement not slippery?” (Camelia). “In winter, the pavements are in more or less good condition. We can’t get to the bus station, and we get discouraged” (Philbert). “In summer, I don’t need transport, just my walker” (Sarah). | “Is there a chance that I’ll find the empty space and be able to board? Will I be able to board and then get off at an accessible stop?” (Camelia). “I’m one of the most dependent users, I won’t be able to give the driver a ticket” (Henry). | “Having accessible fixed-route public buses allows people with disabilities to develop their autonomy” (Henry). “The fixed-route public bus is freedom” (Amber). “I’m surrounded by friends whom I can ask for favors, but you always have to ask, ask, ask” (Sarah). “I don’t have much balance, so when the bus pulls away, it’s often violent. I need time to sit down and position my walker” (Sarah). | |

| INSIDE THE FIXED-ROUTE PUBLIC BUS RTC bus drivers meet contradictory demands. They ask them, on the one hand, not to delay bus journeys and, on the other, to give the time needed to ensure the safety of users in different disability situations: “That creates tension” (Rachel). | “I enter the bus in my wheelchair ‘Please, please, please, can you push yourself’. It’s horrible, because you have to keep smiling, you’re going to say to: ‘Can you move?’ and then they’re going to look at you like: “Bloody hell, you’re disturbing me, you can see it” (Camelia). “For me, finding a seat has been quite easy, the driver says, ‘release the seat’ or people do it of their own free will” (Robert). | “The ramp is not even deployed, and the other passengers do not wait and practically jump over it” (Rachel). “You press the bell to say, ‘I’m going to stop at this address’, the bus driver goes straight off and pretends not to hear you” (Amber). | It is not certain that people who are used to STAC, even if they can, will switch to the fixed-route public bus: “It’s a challenge, people are used to paratransit, because it’s an accessible door-to-door service” (Rachel). “The driver will answer in a disturbing way, as if I’m disturbing his day” (Amber). | “I’m courteous, always smiling and in a good mood” (Philbert). “Suppose I look at the person in the wheelchair with my bad mood eyes, but because I’m in a bad mood for other things. I think people sometimes project, that it’s not always a look from someone who’s upset that the person is disabled” (Rachel) | Conflicts arise between different kinds of populations and mobility needs: “I’m the priority! Even when it comes to holding the bus handlebar! Then the pushchairs, we’re the first priority, aren’t we?” (Ernest). “There are people who seem upset with a disabled person on the bus… That’s the price of disability” (Camelia). “Even if you made the fixed-route public bus 100% accessible, there are still many who prefer paratransit. It’s door-to-door, some people don’t have a choice, but there are also a lot of people who feel that this is part of their social life” (Wilbur). |

| USING PARATRANSIT SERVICES “During the taxi industry crisis, the first demands they meet are for healthcare, work and study. Then leisure, then shopping, that’s going to come later, there are choices to be made” (Rachel). Paratransit forbids passengers from “bringing along large shopping bags” (A). “Paratransit is very expensive. A STAC trip costs 24.75 Canadian dollars. A fixed-route public bus journey costs 4 Canadian dollars” (Rachel). “Drivers helps them out and takes them to their door. That’s what STAC does; fixed-route transport doesn’t do that” (Rachel). | “You must call a day in advance to get a vehicle. There’s no spontaneity” (Gina). “You have to know what you’re going to do before 6.00 p.m. to book for the day after” (Camelia). “You always have to plan a day or two in advance, arrival time, departure time, all that. It’s hard to remember all these appointments and what time I have to be at what place. Whereas with the bus, you get out of your house, you know it’s coming every 15 min” (Wilbur). “Drivers give excellent service: ‘Are you okay? Okay, how are you? Are you wearing your seat belt properly?’ I don’t have a problem with that” (Philbert). | “The vast majority of STAC services are provided by outsourced taxis, and “at the moment, the taxi industry isn’t pulling its weight” (Rachel). Some individuals are bimodal, using STAC mainly in winter and fixed-route public bus otherwise: “In winter they’re in a wheelchair, and they’re on door-to-door STAC service” (Rachel). “I used to lend my adapted car and I never got paid, but it could be a possibility for people who have adapted cars to help other disabled people, like a breakdown assistance community. Even among us, disabled people, some have the means, we can help others” (Camelia). | “The hidden aim, which is admitted but never talked about, is to allow older people to take public transport for longer so as not to overburden the paratransit system” (Henry). “You have to plan too much, I’m trying more and more to familiarise myself with fixed-route public transport, so I don’t have to take paratransit” (Wilbur). | “My independence also comes from transport. Paratransit services was a blow to me because it was my independence” (Sarah). “Paratransit is very infantilizing. When you call the paratransit service to book it, the question they ask you is: “Is it for home? Is it for work? Is it for leisure? What are you going to do there?” (Amber). “Some people are confident on their motor skills in a wheelchair, others do not, and they are the ones who will use paratransit” (Ellen). | “Paratransit has enabled people to become more autonomous, and there are people who also have a life because of it” (Henry). “We’re lucky to have access to paratransit services, like STAC. If that didn’t exist, we’d be in a lot more trouble” (Wilbur). Different people with similar transport needs compete for limited resources: “We’re stuck with other people, either elderly or retired, but we all have the same transport problem” (Camelia). “He says he’s an employee who works here, even though he’s a volunteer, you understand, and the STAC makes it a priority, but someone who calls the STAC and says it’s for leisure, that’s not a priority” (Tom). “You lose out on a lot of spontaneous opportunities. Someone calls you up and says, “Hey, Will, are you coming over to our place today? You would have had to know the day before, to plan your transport, to be able to go” (Wilbur). “Paratransit takes so long and is so restrictive, because they are picking up other users” (Ellen). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mansilla, J.C.; Boucher, N.; Routhier, F. Public Transport in the Disabling City: A Narrative Ethnography of Dilemmas and Strategies of People with Mobility Disabilities. Disabilities 2024, 4, 228-261. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities4010015

Mansilla JC, Boucher N, Routhier F. Public Transport in the Disabling City: A Narrative Ethnography of Dilemmas and Strategies of People with Mobility Disabilities. Disabilities. 2024; 4(1):228-261. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities4010015

Chicago/Turabian StyleMansilla, Juan Camilo, Normand Boucher, and François Routhier. 2024. "Public Transport in the Disabling City: A Narrative Ethnography of Dilemmas and Strategies of People with Mobility Disabilities" Disabilities 4, no. 1: 228-261. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities4010015

APA StyleMansilla, J. C., Boucher, N., & Routhier, F. (2024). Public Transport in the Disabling City: A Narrative Ethnography of Dilemmas and Strategies of People with Mobility Disabilities. Disabilities, 4(1), 228-261. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities4010015