Abstract

Background: Participation is often defined as taking part and being included in different areas of life. Leisure represents an important area of life for all people. People with disabilities have the right to experience leisure time in a self-determined manner. They have the right to participate in leisure activities on an equal basis with others. Due to various influencing factors, people with intellectual disabilities, especially those with severe to profound intellectual disabilities, are at risk of decreased participation. This is alarming because participation in leisure activities reflects quality of life. Purpose: The present study aims to review the empirical findings on leisure participation and its influencing factors in people with mild to moderate disabilities as compared to people with severe to profound intellectual disabilities. Method: A scoping review following the PRISMA-ScR checklist by Cochrane and the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) was conducted to examine research studies published in peer-reviewed journals between 2000 and 2022. The studies that were included relate to activities within the everyday leisure time of people with intellectual disabilities, regardless of age, gender, or severity of their cognitive disability. The categories of vacation and tourism were excluded so as to focus on everyday leisure. The sample was screened by two reviewers independently. In total, 27 articles met the inclusion criteria, with 21 articles referring to people with a mild to moderate intellectual disability and only six articles referring to people with a severe to profound intellectual disability. The evidence was summarized with a predefined standardized charting form, which was used by the two reviewers. Results: The results show that participation in leisure activities by people with intellectual disabilities can be limited, especially for those with severe to profound intellectual disabilities. This contradicts the guiding principle and human rights of inclusion and self-determination. Their participation in leisure time is extremely dependent on external factors, such as support people, leisure time availability, and form of living. Passive activities at home are often provided for people with severe to profound intellectual disabilities in particular; therefore, the need for interactive and self-determined leisure opportunities in the community is enormous. Various factors influencing leisure participation can be identified. Implications: The findings of this scoping review can be used to consider intervention, support, and barriers to enhancing leisure participation among people with disabilities as an important area of life.

1. Introduction

Participation is defined as ‘being involved in life situations’ [1]. Being involved is determined by the limitations of the body’s structures and functions, as well as contextual factors, and manifests itself in the performance of activities, such as communicating, learning, and being mobile. These activities can be assigned to different domains of life, such as self-care, home life, community, and social and civic life. In the domain of ‘community, social and civic life’, participation in leisure activities is defined as consisting of play, sports, culture, crafts, hobbies, and social activities. Dijkers [2] extended the concept of participation. He describes participation as the extent or degree to which people take part in various activities and fulfill specific roles; therefore, participation can be objectively operationalized as active engagement, which can be quantitatively observed by measuring the duration and frequency. Qualitatively, leisure time participation can be assessed through subjective perceptions of leisure time. As people with severe or profound intellectual disabilities often communicate nonverbally using idiosyncratic symbols [3], their leisure participation can be observed through expressions such as mimicking and gesturing emotions, including pleasure, happiness, and/or enjoyment [2,4,5]. Whilst participation is important in all areas of life, this scoping review focuses on participation in leisure activities of people with intellectual disabilities (ID) and the influencing factors of various activities.

It is necessary to increase our knowledge of leisure participation and its influencing factors on people with mild to profound intellectual disabilities to enable participation and increase their quality of life. For this purpose, a scoping review was performed because it represents a method for screening and synthesizing the state of research on a broad topic, such as leisure participation. To the authors’ knowledge, until 2022, there were seven reviews on community participation and intellectual disability, social participation and intellectual disability, and participation in outside school activities among people with different disabilities [6,7,8,9,10,11,12]. We are not aware of a review that encompasses a compilation of empirical findings on leisure participation in the context of intellectual disability. In order to gain in-depth knowledge on the leisure participation of people with intellectual disabilities, we conducted this scoping review by comparing empirical findings on the leisure participation of people with mild to moderate intellectual disabilities with findings on the leisure participation of people with severe to profound intellectual disabilities. The factors influencing leisure participation for people with intellectual disabilities were identified and compiled.

2. Leisure as an Important Domain of Life

Leisure time has become increasingly important in the course of the post-industrial reduction in working hours [13,14]. In addition to the quantitative increase in free time, social developments in Western societies have led to a change in the way it is treated. While free time has long been viewed as ‘leftover’ time distinct from working time [15], qualitative characteristics, such as self-determined freedom to shape one’s own life, are now seen as hallmarks of this period of time [16]. Thus, in the discourse of leisure research, different concepts of leisure exist, which can be shaped by different disciplines. In summary, leisure can be viewed in various ways:

- As activity—some activities involve planning, the use of facilities or equipment, and the involvement of other people. Others are much more spontaneous.

- As time—leisure takes place in ‘non-obligated time’, in other words, those occasions when we are free of responsibilities and the demands of others.

- As a state of mind—when we feel free to choose our activity to please ourselves, without external pressure or rewards [17].

Leisure time plays an important role in the lives of all people. Especially in the course of identity development in adolescence, leisure time represents an area of life in which adolescents can learn more about themselves and define their character apart from adults [18]. Free time provides the space and freedom of action to try new activities, demonstrate skills, connect with others, and stand up for and express oneself. Numerous studies demonstrate the qualitative value of free time in the lives of people (e.g., [19]). Social roles, values, and norms can be tried and tested in leisure. Leisure beckons opportunities to experiment with these qualities and to test and develop facets of oneself. Engaging in new activities during leisure time offers opportunities to discover new interests, pursue one’s intrinsic motivation to engage in activities, and form relationships with others. Thus, social–emotional development is strengthened, and empathy, self-determination, self-efficacy, and autonomy are promoted [20,21]. However, Larson [21] points out that autonomy is not unconditional. For example, there are many people who have only limited opportunities to develop their decision-making competence due to influencing factors, such as time determined by others, limited options for action, little time, and/or a high level of dependence on others. Leisure activities in particular are based on the principle of voluntariness. They are therefore well suited for learning and consolidating autonomy and self-determination while taking the social context into account. Participation in social leisure activities can promote community participation and inclusion. In this regard, Doistua et al. [22] distinguished between guided and self-organized leisure activities. When people have the opportunity to organize their leisure time according to their wishes in an intrinsically motivated way, they not only experience leisure time positively, but their satisfaction also increases. Leisure time has a great impact on the quality of life [23]. Thus, leisure participation affects emotional, social, mental, and physical well-being. Leisure represents an area of life that affects all people. People with disabilities also have leisure needs, just like any other person. To promote inclusive participation in leisure, contextual factors are needed that enable the person to find, access, and benefit from leisure opportunities. Aitchison [24,25] considers the study of disability and leisure to be important to make leisure inclusive.

3. Leisure Participation of Individuals with Intellectual Disabilities

Research indicates that children and adolescents with a wide range of intellectual disabilities experience limitations in leisure participation within their community environments [26,27,28]. Melbøe and Ytterhus [29] investigated what types of activities adolescents with intellectual disabilities participate in during their free time. The study shows that youth with intellectual disabilities have the same preferences and desires for leisure activities as their peers without disabilities. However, a closer look reveals that youth with intellectual disabilities lack access to institutionally organized leisure activities, thus limiting their ability to express their preferences, which negatively impacts their well-being [23]. Buttimer and Tierney [28] suggested in their study that the leisure activities of young people with intellectual disabilities are predominantly passive and medial in nature. This type of leisure activity is often carried out alone within their home. In addition, the parents of children with disabilities cite a lack of friendships, the feeling of ‘not being welcome’, and a lack of leisure-oriented skills as the most frequent barriers to leisure activities. Leisure time increasingly takes place in the individual private sphere, and social participation and the choice of leisure activities seem to be limited. However, a study by Eratay [30] shows that leisure activities in particular offer opportunities for social interaction, which in turn can have a positive effect on the development of social skills and a reduction in behavioral problems in young people with intellectual disabilities. In addition to social action, self-determination and the subjective attribution of meaning in the performance of leisure activities are recognized as important elements of leisure participation [19,21]. Thus, the environment represents an important determinant when it comes to participation [10]. For individuals to be able to act in a self-determined manner, they need choices in their environment that they can intentionally decide on based on their needs and competencies. Eldeniz and Cay [31] examined school-based leisure support for students with intellectual disabilities. They found that participation in leisure activities increases when students are allowed to choose the leisure activity on their own. If the teacher determines the activity, the active participation of the students is lower. Dahan-Oliel, Shikako-Thomas, and Majnemer [32] conducted a systematic review of the relationship between leisure participation and quality of life in children with neurodevelopmental disorders. They were able to show that active physical leisure participation is related to increased physical and emotional well-being, that successful leisure participation with others results in increased social well-being and increased self-efficacy, and that exercising leisure preferences is related to well-being and individual satisfaction. The promotion of participation in leisure activities by adolescents, therefore, seems to be an important concern in the context of quality of life. Studies on leisure participation of adults with intellectual disabilities also show similar results. Badia et al. [23] investigated the relationship between leisure activities and the quality of life of people with developmental and intellectual disabilities. They found positive correlations between the expression and exercise of leisure preferences and individual well-being. Participants with disabilities who perceive limitations in their participation in leisure activities show lower levels of emotional and physical well-being [33].

4. Method

4.1. Scoping Review Questions

A scoping review methodology was chosen because this methodology enables a rigorous review of a broad topic area as opposed to a more narrowly defined systematic review. Scoping reviews are a good method for pooling or communicating research findings, identifying research gaps, and making recommendations for future research [34,35]. It is an appropriate method to meet the aims of this study, given that participation is a complex concept and, as we know, has not been reviewed before in the context of leisure activities of people with intellectual disabilities. The goal of the review is to provide an overview of the available evidence on the leisure participation of people with mild to moderate intellectual disabilities in comparison to individuals with severe to profound intellectual disabilities. The conducted scoping review is based on the methodology developed by the Joanna Briggs Institute and follows the manual for scoping reviews [36]. The following was our guiding research question:

- What perspectives for action and research can be identified to support and ensure the participation of people with intellectual disabilities in leisure time?

Since people with intellectual disabilities are at risk for decreased participation in leisure activities [28,29], which affects various dimensions of the quality of life [37,38], the following questions were explored to address the guiding research question:

- What characteristics are used to define leisure participation for people with mild to moderate intellectual disabilities and for people with severe to profound intellectual disabilities?

- What are the patterns of participation in everyday leisure activities of people with mild to moderate intellectual disabilities in comparison to people with severe to profound intellectual disabilities?

- What are the factors that facilitate or hinder the use of leisure time and participation in leisure activities of people with intellectual disabilities?

4.2. Review Protocol

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria and Search Strategy

To complete the scoping review, we developed a review protocol based on the scoping review questions mentioned above. First, we identified the core terms based on the PCC framework (population, construct, context) recommended by the JBI manual [36,39]: as core terms for the population, we determined people with intellectual disability following the revision of the ICD-11 [40]:

- Mild intellectual disability;

- Moderate intellectual disability;

- Severe intellectual disability;

- Profound intellectual disability.

We then derived the first inclusion criterion. We only focused on studies that had people with intellectual disabilities in their sample or as a part of a larger cohort of participants. As an exclusion criterion, we did not consider studies that did not have people with intellectual disabilities in their sample. Studies with people with dementia, minimal consciousness, unconsciousness, or another disability or chronic condition without an intellectual disability were excluded. We also did not focus on people with autism spectrum disorders because of the limited time frame of the review and because there is already a scoping review on patterns and determinates of leisure participation in this population [41]. Another core term was participation; therefore, we included only the studies that deal with the conceptualization of participation [42]. With the core term ‘leisure’, we narrowed the construct participation of people with intellectual disabilities in the context of leisure time. Studies were included that either used the term ‘leisure’ in the title or had ‘leisure’ set as a keyword. Thus, only studies were included if they were related to participation in leisure time or activities. It did not matter whether the studies explored participation in informal (unstructured/spontaneous) leisure activities (e.g., at home) or formal (structured/preplanned) leisure activities [43]. Studies with a focus other than participation in everyday leisure activities, for example, studies that focused on participation in therapy, self-care, tourism, and/or traveling, were excluded.

To refine the search, other inclusion and exclusion criteria were chosen. We limited the search to articles written in the English language in peer-reviewed journals because this guarantees the scientific value of the studies and the reliability and trustworthiness of the data to provide a review of the empirical research literature [44]. We confined our search to the period of 2000–2022. This time period was chosen because, in 2001, the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) was officially endorsed by all 191 member states of the World Health Organization (WHO) as the international standard for describing and measuring health and disability. Furthermore, the time period was chosen to ensure the review is up to date with the latest research on the topic. In addition, the interaction of people with intellectual disabilities within the community from the late twentieth century to today is characterized by the paradigms of self-determination, inclusion, participation, and community care. For these reasons, we conducted our search between 2000 and 2022. Additionally, only full-text versions were included in our review. Articles without open access or access via an institutional login to review the full text were excluded.

The research team identified relevant studies within ERIC, PubMed, PSYNDEX, and PsycINFO. The databases were selected through the EBSCOhost information service and searched sequentially. Reference lists of relevant articles were also hand-searched to identify any additional sources. The search terms were generated by performing an initial search using Google Scholar and identifying important keywords in publications. Additional core terms based on the PCC framework recommended by the JBI manual [36,39] were systematically divided into search terms [34].

The search terms were entered in the following sequence: (a) participation OR engagement OR involvement AND (b) cognitive disabilit* OR developmental disabilit* OR intellectual disabilit* OR special needs OR profound intellectual and multiple disabilit* OR profound and multiple learning disabilit* OR profound intellectual disabilit* OR severe intellectual disabilit* OR severe to profound disabilit* OR complex needs [3] AND (c) leisure OR leisure time OR leisure activit* OR recreation* OR hobb* OR play* OR free time [41].

4.3. Study Selection

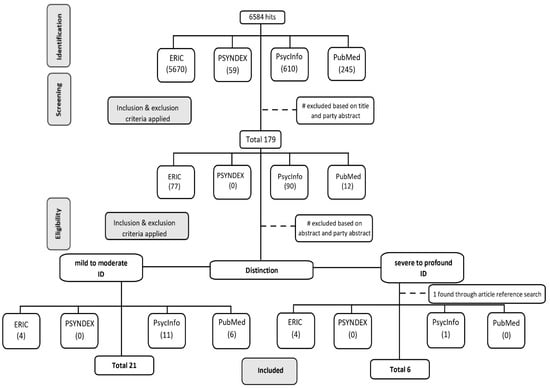

We considered both UK and US English terminology, and singular and plural forms. The search produced 6584 results because we used the functions ‘apply related words’ and/or ‘apply equivalent subjects’ of the databases. In an initial scan, we screened the titles and applied the previously established inclusion and exclusion criteria. Most of the studies were excluded because the term ‘leisure’ was not mentioned in the title or because a different target group other than people with intellectual disabilities was specified in the title (n = 6292). Duplicates, doctoral theses, and reviews with another topic were removed (n = 109). We excluded four studies that focused on the development or validation of a diagnostic instrument. In cases of uncertainty, the study titles were marked, and both reviewers independently screened the title and abstract. The first screening resulted in 179 hits. In the second scan, all 179 titles, abstracts, and full texts were reviewed by the two independent reviewers based on the review questions and the previously established inclusion and exclusion criteria. In this process, we excluded any publications that did not report an empirical study (n = 9). All the duplicates (n = 14) and abstracts without access to a full-text version (n = 19) were removed. According to our working definition, study participants had to have an intellectual disability without Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). Studies with participants with dementia, minimal consciousness, or unconsciousness, or without an intellectual disability were excluded. Therefore, we excluded a total of 77 publications because most of these studies included participants without intellectual disabilities. Finally, several studies were excluded because the subject differed from the subject of this review (n = 33). Thus, we excluded a total of 152 studies because of the above-mentioned reasons. A total of 27 studies were selected for this scoping review (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the study selection process.

4.4. Study Charting and Analysis

To collect the data regarding the research questions of the review, we developed a predefined standardized charting form as a team. The charting process was multi-staged, involving data extraction from each article. The descriptive characteristics for all the selected studies, such as authors, date and country of the publication, participants (sample size, diagnosis, age), type of study, outcome measures, type of leisure participation, and main findings (pattern of leisure participation and factors influencing participation) were extracted and organized. Table A1 in Appendix A includes studies of leisure participation with participants with mild to moderate, and severe to profound intellectual disabilities. The summary tables of the study data were used to examine and compare the main findings to determine the pattern and influencing factors of participation in leisure time among people with mild to moderate and severe to profound intellectual disabilities.

5. Results

5.1. Overview

Four major databases were systematically searched for studies on leisure participation among people with ID. A total of 23 relevant articles were found for people with mild to moderate ID, and only four studies were found that addressed leisure in the context of severe to profound ID. Of the 23 studies, two have a subsample of people with severe to profound ID; therefore, we assigned these two studies to this population (n = 6).

The evidence is descriptive and about 70% of the articles (19 of 27) focused on the participation patterns of people with ID, with 10 studies (37%) also addressing the influencing factors, barriers, and facilitators of leisure participation.

The selected studies were published between March 2001 and September 2022. Among the articles included, the number of published articles through the years was balanced. Within our review search, we found seven published articles between 2001 and 2006 (n = 7; 25.9%). Between 2007 and 2011, six studies (n = 6; 22.2%) could be identified. Eight studies (n = 8; 29.6%) were published from 2012 to 2018, and between 2019 and 2022, six published studies (n = 6; 22.2%) could be found. Most of the studies were conducted in the USA (n = 5; 18.5%), followed by Israel and Spain (n = 4; 14.8% (each)), Canada and the Netherlands (n = 3; 11.1% (each)), Norway (n = 2; 7.4%), Sweden, India, UK, Germany, Australia, and Ireland (n = 1, 3.7% (each)). In regard to the study design, most of the studies were quantitative (n = 19; 70.4%) in nature, and only eight studies (29.6%) had a qualitative study design. In the 27 studies, different age groups were identified in the samples. Pochstein [45], Dolva et al. [46,47], Taheri et al. [48], Solish et al. [49], and Buttimer and Tierney [28] identified children and/or adolescents with mild/moderate ID as the target groups in their study (n = 6; 22.2%). Among their sample group, Duvdevany and Arar [50], Yalon-Chamowitz and Weiss [51], Patterson and Pegg [52], Lövgren and Rosqvist [53], Hall [54], and Mihaila et al. [55] only included adults with mild to moderate ID who were over 18 years of age. Adults with severe to profound ID were in the target group in the studies by Yu et al. [56], Zijlstra and Vlaskamp [57], Wilson et al. [58], and van Delden et al. [59]. Overall, n = 10 (37%) studies examined leisure time participation among adults 18 years and older. Cross-age target groups were found in the research by Beart et al. [60], Sellinger et al. [61], Azaiza et al. [62], Badia et al. [23,26,27], Dusseljee et al. [63], Dykens [64], Venkatesan and Yashodharakumar [65], and Doistua et al. [22] (n = 9; 33.3%). Gilor et al. [66] did not specify the age of their sample (n = 1; 3.7%).

5.2. Definitions and Assessment of Leisure Participation

5.2.1. Participants with Mild to Moderate ID

The fact that leisure can be viewed from different perspectives [17] is also reflected in the operationalization of leisure participation within the different studies. Assessments of leisure participation among people with mild to moderate ID often demonstrate a quantitative research design and frequently involve surveying leisure activities that the participants are currently engaged in [23,28,46,55,63,64] and recording leisure parameters, such as with whom the activity is performed [48,49], in which environment or location the activity is performed [27,46,50,60,65], when the activity is performed, how often the activity takes place, and how often the person with a disability participates [48,57,61]. In the studies, leisure is seen as both an activity and as free time [17]. In addition to measuring leisure time activities, factors such as age, gender, the severity of disability, type of organization, type of housing, assistance/support, and friendships are often surveyed [22,26,27,28,48,50,55,61]. Questionnaires were used in 14 of 21 studies (66.6%). Standardized measures of leisure participation included the leisure activities list (n = 1) [50], the TRAIL Leisure Assessment Battery (TLAB) for people with cognitive impairments (n = 2) [28,55], the activities questionnaire (n = 3) [48,49,61], the Spanish version of the leisure assessment inventory (n = 3) [23,26,27], and the recreation and leisure questionnaire (n = 1) [64].

Some of the researchers used qualitative methods, including focus group interviews (n = 2), semi-structured interviews (n = 4), structured interviews (n = 1), activity logs (n = 1), field visits (n = 1), and observations (n = 1). In 6 of the 21 studies (28.6%) with participants with mild to moderate ID, only proxy surveys were conducted [46,48,49,61,64,66]. In three other studies, the proxies and the people with ID were defined as the sample group [28,45,55]. Overall, proxy surveys were found in more than one-third (n = 9; 42.7%) of the 21 studies.

The studies with a qualitative research design (n = 8; 38.1%) more strongly address the subjective dimension of leisure participation. In this way, questions are asked not only about the leisure activities carried out, but also about other leisure preferences, wishes, interests, and barriers experienced. Emotions (e.g., happiness, satisfaction, loneliness) during the leisure experience and the experience of assistance, independence, self-determination, self-esteem, and control were also a point of focus [28,60]. The themes of social interactions, friendship, and social belonging during participation in community-based leisure activities can be found in Patterson and Pegg [52] and Hall [54]. Overall, the qualitative studies tend to examine the subjective meaning of participation in leisure time [28,53,60] and highlight subjectively experienced barriers and opportunities. Leisure participation as a state of mind [17] is taken into account here. When proxies were interviewed, the interviewers explored the difficulties in organizing and implementing leisure activities for children with ID [66], and developed an assessment regarding a sports program in which children and adolescents have participated [45].

5.2.2. Participants with Severe to Profound ID

Studies on leisure time participation in the context of severe to profound ID have a solely quantitative study design (n = 4), which partly focuses on the qualitative aspects of leisure participation. As Badia et al. [23,26,27] also included people with severe ID in their sample groups, we included these two studies; therefore, we assume six studies for this group of individuals (n = 6; 22.2% out of 27 studies). van Delden et al. [59] used a single-case design with inter-case replication, as well as within-case replication. They conducted a study with an interactive ball that responds to body movements, attention, and vocalization of users with profound intellectual and multiple disabilities (PIMD). The goal of the study was to record and increase attention, body movement, and negative as well as positive vocalizations, and to reduce negative emotional expressions. The instruments used were the alertness observation list according to Vlaskamp [67] and an observation scheme for affective behavior. To measure movement, they used computer vision. Wilson et al. [58] focused on leisure engagement in naturally occurring leisure times. They also conducted a single case study in an A–B–A design. They asked about popular leisure activities and instructed staff to provide choices to participants after an initial observation period without intervention. The direct support staff was trained to provide choices in a paired-item manner in the respective participant’s home individually. Wilson et al. [58] observed the participants to determine if their engagement in leisure activities changed. Leisure engagement was defined to include motor movement, communication, and/or attendance, while turn-taking is related to a leisure activity. Engagement resulting from motor movement involved the manipulation of a leisure material or movement related to a specific leisure activity. They used an observation system as an instrument. Yu et al. [56] observed happiness indices during naturally occurring work and leisure activities for individuals with severe and profound disabilities. Both groups showed more happiness indices during leisure than work activities. Three studies [23,26,57] measured more quantitative objective characteristics of leisure time participation. The actual leisure time of 160 individuals with profound intellectual and multiple disabilities was recorded over four weekends by Zijlstra and Vlaskamp [57]. They examined the relationship between the characteristics of the setting and the distribution of the content, frequency, and duration of leisure activities of individuals with profound intellectual and multiple disabilities in different residential facilities. The information about the sample and the leisure activities offered was collected with the help of two instruments: a questionnaire and a diary. The direct support professionals documented in both instruments. The questionnaire was used to obtain information about the selection of the leisure activities. In addition, they were required to evaluate the leisure activities offered to the participants. The diary consisted of a semi-structured questionnaire containing questions about the type of leisure activities offered to the participants, the frequency and duration, the location of the leisure activities, the size of the group, and the time when the leisure activities took place. Badia et al. [23,26] examined the type and number of leisure activities and activities in which the individual would like to increase their participation, the degree of unmet leisure involvement based on the selection of activities in which the individual has an interest but in which they are not participating, and internal and external barriers to leisure participation.

Overall, the methods that can be identified are observations (n = 3), questionnaires (n = 3), a diary (n = 1), and structured interviews (n = 2). The interviews, questionnaires, and diary were completed by proxy by the support staff. Standardized measures included the alertness observation list (n = 1) [59] and the Spanish version of the leisure assessment inventory (n = 2) [23,26].

5.3. Patterns of Leisure Participation

5.3.1. Patterns of Leisure Participants with Mild to Moderate ID

Over half of the studies focused on the quantitative aspects of leisure activities for people with ID. They examined specific patterns regarding the types of activities, amount and frequency of activities, participation in activities, locations of the activities, and who joined during leisure time.

The study results suggest that individuals with mild to moderate ID tend to participate less in social and recreational activities than normally developing children [49,62]. Buttimer and Tierney [28] found in their study that the most commonly cited social and communicative leisure activity of adolescents and young adults with mild to moderate ID was talking on the phone. The study results report that people with mild to moderate ID often carry out solitary, passive, and sedentary leisure activities [27,28,64,65]. These activities include, for example, watching TV, playing computer games, listening to music, or reading [27,28,46,64]. In contrast to these studies, other studies have shown that adolescents with ID are both active and sociable in their leisure time [46,48]. Dolva et al. [46] pointed out that social participation of adolescents with mild to moderate ID largely involved parents and family, while socializing with other adolescents mainly took place within formal activities adapted for disabled people. Through discussions with the parents of children with ID [46], about 372 leisure activities were able to be cited, which can be divided into physical (44%), hobby and recreation (25%), computer and media (23%), and cultural activities (18%). This division into subgroups also can be found in other research, for example, in Mihaila et al.’s [55] study. They focused on the frequency of leisure activities and examined physical leisure (0.59 h/day), social activities (1.11 h/day), cognitively stimulative activities (1.25 h/day), and passive leisure activities (2.40 h/day) [55]. Other studies have shown that social leisure activities decline with age [27,53,63]. Lövgren and Rosqvist [53] found that middle-aged people with mild to moderate ID in Sweden do have not enough leisure activities to carry out in their free time besides household chores, preparing for their job, or meeting relatives/friends.

Some other studies have shown that leisure participation in the community can be more difficult for people with ID [11,27,63,65]. The findings indicate that people with mild to moderate intellectual disabilities primarily use segregate leisure opportunities in the community that are not used by people without disabilities [46,54,60,63]. Hall [54] and Beart et al. [60] pointed out that most of the participants from their samples were a part of special groups for people with disabilities (e.g., day centers) for carrying out leisure activities [60], especially for recreational hobbies, sports, and social connections [54]. Regarding leisure involvement, Patterson and Pegg [52] reported that people with mild to moderate ID have the ability to participate in serious leisure activities. These activities enable them to develop increased levels of confidence, skills, and self-esteem [52]. They found that many participants in their study were engaged in activities for at least two years and up to fifteen years.

It seems that the type of leisure activity determines the place of leisure experience. This is especially true for physical activities that take place outside in the community, whereas cognitive stimulating activities are almost always carried out at home [27,55,64]. It appears that social activities are almost evenly distributed between home and community locations [27,55]. Venkatesan and Yashodharakumar [65] discovered that people with ID are more frequently involved in indoor leisure activities than in outdoor activities. Beart et al. [60] disproved the hypothesis that most leisure activities for people with ID are home-based; in their sample, only 22 out of 86 leisure activities were home-based.

The patterns regarding who joins in during leisure time differ significantly. Some studies have shown that people with mild to moderate ID wish to have more interaction from partners/friends who join their leisure activities and not to do everything on their own or only with family members [27,28,45,49]. As mentioned above, frequently reported leisure activities at home can include watching TV, listening to music, or playing computer games [27,28,46,64]. Dolva et al. report that nearly half of the named activities were carried out alone [46]. This is confirmed by Mihaila et al. [55], who found that over half of people with Down syndrome in their research carried out physically and cognitively stimulating activities on their own. Other studies have shown that social activities or cultural activities are predominantly enjoyed together with family members or sometimes with friends [46,47,49,55]. Thus, Dolva et al. [47] and Solish et al. [49] discovered that, in leisure activities, people with mild to moderate ID engage most often with family members and less with their peers or other adults by group [49]. The study of Duvevany and Arar [50] provides evidence that an individual with ID with more friends will have increased levels of participation in leisure activities.

Some studies also focused on the qualitative aspects of leisure activities. They examined preferences, experiences, and enjoyment during leisure activities. The children with mild to moderate ID in Pochstein’s [45] sample talked about their former experiences with sports clubs and inclusion. Most of them were often left out or even bullied by teammates. After partaking in Pochstein’s [45] program, most of them talked about the fun they had and that they found friends at the sports club. Only two of them noted that they did not feel very welcome [45]). Badia et al. [27] researched the preferences of people with ID, and their sample wished to increase social activities even though they were already engaged in a lot of different social activities. They also preferred to have more active leisure at home (e.g., cooking) [27]. Doistua et al. [22] show that self-organized leisure time was associated with higher perceived psychological (emotional and cognitive) benefits. According to Dolva et al. [46], half of all leisure activities are chosen by people with ID themselves (according to the parents’ reports), and the most common motive for choosing an activity was their interest in the activity. Other feelings during leisure activities were highlighted by Yalon-Chamovitz and Weiss [51] and Patterson and Pegg [52] in their studies. Thus, the motives for engaging in leisure activities were success and developed preferences (in VR games) [51] or increased self-confidence, skills, and self-esteem [52].

5.3.2. Patterns of Leisure Participants with Severe to Profound ID

The quantitative aspects (patterns/types of activities, places for activities, and partners during activities) for people with severe to profound ID dominate the research. Wilson et al. [58] found in their study that nearly no leisure activities were carried out by the majority of people (78%) with severe ID living in supported independent living settings. The findings are supported by Zijlstra and Vlaskamp [57]. They found that the leisure time of people with profound intellectual and multiple disabilities (PIMD) contains many empty hours and less quality time [57]. However, they also examined in their study that most people with profound intellectual and multiple disabilities are offered two to five possible activities each weekend [57], ranging from ‘audio–visual media’, ‘physically orientated activities’, or ‘play games’. The mean duration of leisure activities during one weekend was 3.8 h per person. In contrast to those activities that are more passive in nature, van Delden et al. [59] presented nine people with profound intellectual and multiple disabilities a technological ball with lights and special effects. Clearly positive effects in alertness, affective behavior, and movements were experienced for one participant. For the others, only alertness and affective behavior could be increased [59]. This could lead to more active leisure activities for these people.

The studies by Wilson et al. [58] and Zijlstra and Vlaskamp [57] provide evidence for locations where leisure takes place for people with severe to profound ID. The findings of Wilson et al. show that most of the offered leisure activities are home-based for people with severe to profound ID [58]. Zijlstra and Vlaskamp [57] found that people with PIMD spent most of their weekend time in their residential units or facilities, and that the duration of interactions in leisure time was very limited for most clients.

For people with severe to profound ID, it is essential to receive offers for choosing leisure activities. Wilson et al. [58] showed the importance of staff members’ presentations of leisure activities to people with severe intellectual disabilities. Without showing them different options, no leisure activity could be observed [58].

Regarding the qualitative aspects of leisure activities among people with severe to profound ID, Yu et al. [56] determined from their research that the happiness index of their sample was higher during leisure activities compared to work activities.

5.4. Influencing Factors on Leisure Participation

Various factors can be found in the studies that can influence the participation of leisure time of people with ID. We have structured these according to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) by the World Health Organization [1]. Since the factors affect people regardless of their severity of intellectual disability, we have not presented the comparative results for people with mild and moderate intellectual disabilities and for people with severe to profound intellectual disabilities. It is important to recognize that participation in leisure activities is a basic human right and should be provided to all people, regardless of their intellectual abilities. Therefore, efforts should be made to identify factors for participation and remove barriers. The following influencing factors can be found in the various studies.

5.4.1. Body and Mental Functioning

Several body and mental functioning aspects correlate with the types, frequencies, and participation in leisure activities. Azaiza et al. [62] posited that cognitive functioning is highly positively correlated with participation in leisure activities. Slight correlations between the health condition, physical functioning, and leisure participation were also examined by Azaiza et al. [62]. Contradictory results were found regarding the type, severity, and received medications: Badia et al. [26] determined that no disability-related factors were significantly relevant, whereas in the research of Badia et al. [27], the type of disability correlates with the types of activities. In Venkatesan and Yashodharakumar [65], the frequency of leisure activities correlates with the type of disability. In addition, Solish et al. [49] found that the number of friendships correlates with the type of disability. Doistua et al. [22] found that the type of disability was related to the degree of self-management in leisure. In addition, there was a significant relationship between the degree of satisfaction with leisure and the degree of self-management related to leisure. This relationship varied depending on the type of disability. Some studies showed that the type of genetic syndrome also impacts the types of activities chosen [55,61,64]. The severity also seems to be an influencing factor: it seems that people with profound, severe, or moderate ID participate less in activities than people with mild ID [27,57,63,65]. Dykens [64] found that the physical health of the individuals also impacts the type of leisure activities because a higher BMI is negatively correlated with physical play. Dykens [64] and Taheri et al. [48] also found that a higher IQ and adaptive behavior positively correlates with computer games and physical activities.

5.4.2. Activity Limitations

Leisure participation and leisure interests and preferences are related to the type and severity of disability [26,27], as well as adaptive behaviors [48], such as mobility-related [28,66] and social [49,50,54] skills. This is also evident in making friends. Children without disabilities have significantly more friends than children with ASD or ID [49]. Taheri et al. [48] used behavioral scores to assess the adaptive and maladaptive behaviors of children with ID. Their results indicate that adaptive behavior is an important predictor of activity participation [48]. A higher adaptive skill level can result in greater activity participation. They showed that participation of individuals with ID was highly linked to their gross motor function, manual and cognitive ability, and communicative skills. Doistua et al. [22] showed that the type of disability relates to the degree of self-management associated with leisure.

5.4.3. Contextual Characteristics

Personal Factors

One of the most important personal factors is the engagement of parents of children with ID [46,47,55]. Parents offer them different opportunities, drive them to various locations, and help organize leisure activities. Lövgren and Rosqvist [53] showed that many personal factors result from the lack of a strong voice/vulnerability. The diversity of people with ID is also a factor that influences their leisure activities [57,66]. During leisure activities, the adaptive behavior of people with ID is a decisive factor [48,52]. Additionally, their age has an impact on how they participate in leisure activities: younger people participate more in social, physical, and recreational activities [26,27,57,63]. Gender has an impact on the type of activities chosen: studies showed that male participants participated more in physical leisure activities than females [26,27,64]. The personal financial resources of people with ID [53,62] and a lack of time for leisure activities [28,53] are additional personal factors. Azaiza et al. [62] found that people who are employed and connected with colleagues at work engage in more leisure activities than unemployed people.

Environmental Factors

There are several geographic, economic, cultural, and social factors (e.g., national policy, social inclusion, and society’s negative attitude) [26,28,45,47,50,52,60,62,66] that can hinder or facilitate leisure participation and leisure service utilization. Suitable access to activities/sports clubs and adequate support (e.g., giving appropriate encouragement or staff presentations [52,58]) during these activities is essential for people with ID to participate in leisure activities [45,60,62]. Not only can access to clubs and activities be a challenging obstacle, but it can also be difficult to pay membership fees and acquire necessities, such as equipment [60]. Other research has found that the type of residence that people with ID reside in and who they live with are important factors: living together with their own family or in foster homes can increase leisure activities [27,50]. It seems that the type of residence (rural, town, or city) or foster home/community setting can influence the possibilities of leisure activities [27,46,50,57].

Other environmental factors include a lack of places for carrying out certain types of activities [28,55] and a lack of friends/social support [45,46,49,60]. Important factors for leisure providers include transportation, information, and qualified staff [26,27,45,55,60,66]. Some studies have found that the type of education a child receives also has an impact on their participation in leisure activities (inclusive schooling) [26,27,48,63].

6. Discussion

Overall, our findings suggest that participation in leisure activities is limited among people with ID, especially those with severe to profound ID. The majority of people with severe to profound ID engage in almost no or few leisure activities. Their participation in leisure time is extremely dependent on external factors, such as support people (and the given choice), the leisure time offered, and the form of living [57,58]. Zijlstra and Vlaskamp [57] and Wilson et al. [58] noted the importance of skilled staff to provide leisure opportunities for people with severe to profound ID. Zijlstra and Vlaskamp [57] showed that staff select inadequate leisure activities. According to them [57], staff seem to lack knowledge and techniques to provide activities for people with PIMD. There are various techniques to provide leisure opportunities for people with severe to profound ID. For example, support people can break down the activity (such as a preferred game) into sequential small steps so that they can be understood and performed jointly. The use of visual supports can also help in perceiving leisure, recognizing and understanding activities, or facilitating communication during leisure activities. Techniques such as modeling and prompting can assist in carrying out the leisure activity. Support people must be familiar with these methods and be able to apply them. Zijlstra and Vlaskamp [57] also noted that staff have too little time to provide appropriate leisure activities. Oftentimes, they are involved in other tasks in the homes, such as nursing, housekeeping, therapies, etc. Staff therefore need more time to be able to offer suitable leisure activities. The awareness of the importance of leisure experiences must be anchored in facilities for people with ID, and time must be available for leisure activities.

In order for people with ID to experience leisure time in a subjectively meaningful way, they need offers that correspond to their interests and leisure needs. If individuals with severe to profound ID are offered only limited leisure opportunities [57], they may be restricted in discovering their leisure interests and developing the corresponding leisure competencies. For people with severe to profound ID, hardly any studies on leisure preferences can be found. One reason for this could be that leisure time is recognized as less important for this group of people, along with therapies, support, education, etc. Another possible explanation is that uncertainties in working with individuals with severe to profound ID may contribute to a lack of opportunities for developing and addressing leisure preferences.

In order to provide subjective meaningful leisure choices to people with severe to profound ID, support people must know the leisure preferences of these people [58]. Wilson et al. [58] emphasized the importance of self-determined and self-selected leisure activities. Support people must be able to perceive, read, and understand the communicative signals of people with severe to profound ID, who often communicate non-verbally [3]. Thus, decisions for a leisure activity can be made with even the smallest communicative signals, such as a wink, the tensing of muscles, or other individual idiosyncratic behaviors. Passive activities at home are often provided for this group of people in particular; therefore, the need for interactive leisure opportunities in the community is enormous [57,59]. Under the conditions of the review, more studies on leisure participation of people with mild to moderate ID can be found than on leisure participation of people with severe to profound ID. Examining the results on the leisure patterns of people with mild to moderate ID, it can be seen that they often engage in passive leisure activities [27,28,64,65]. In this regard, reading, listening to music, and watching television represent popular activities at home, most of which are spent alone [27,28,46,65]. Outside the home, leisure activities are attended in special groups for people with intellectual disabilities in the community [46,54,55,60,63]. All things considered, this contradicts the guiding principle and human rights of inclusion and self-determination. The desire to make new friends is prominent, especially among children and youth with ID [23,28], and can increase their participation in leisure activities [50]. There is an urgent need for leisure opportunities in the community that can be found, accessed, and used without barriers. Inclusive offers must be created so that people with and without disabilities can experience leisure time together. However, qualitative studies show that feelings of ‘not being welcome’ and exclusion [28,45,60] are also experienced. Inclusive leisure opportunities can emerge when providers and users bring a positive attitude regarding inclusion. The studies show that the experience of leisure is associated with feelings of satisfaction and happiness [22,45,56]. Experiencing self-efficacy, control, success, and learning new skills also speak in favor of engaging in leisure activities and represent subjective motivations, even among people with ID [51,52].

The results concerning the factors influencing leisure participation show that participation is a complex phenomenon. Leisure participation is influenced by the body and mental functioning, activity limitations, and contextual characteristics. The findings underscore the value of the ICF as a framework [1] for analyzing and understanding the participation experiences of people with ID. While participation is influenced by personal factors of age, gender [26,27,53,57,63,64], and behavioral dispositions [28,48,49,52], other environmental factors, such as social support from parents or support people [46,47,55], school affiliation [26,27,48,63], leisure provision, transportation, and access to services in the community, are also very important [26,27,45,55,60,66]. Interestingly, the diagnosis of intellectual disability or cognitive functioning was significantly correlated with leisure participation in the study by Azaiza et al. [62]. Other studies (e.g., [26,65]) show no correlation or an activity-specific correlation. Similar findings can be found in studies of children and adolescents with developmental disabilities [9,68]. Additionally, similar patterns of participation and influencing factors can be found in a scoping review on the participation of children and youth with disabilities in activities outside of school by Tonkin et al. [10].

By examining the differences in leisure participation between individuals with mild to moderate ID and those with severe to profound ID, we can derive the following possible hypotheses or explanations: one possible explanation for differences in leisure participation could lie in activity-related demands. Every person has action competence, but activity demands must correspond to action competence, or the demands must be adapted to individual competencies. If no adaptation (e.g., for playing a game, understanding game rules, etc.) takes place, participation remains limited or reduced. Designing leisure activities that match the abilities of individuals with severe to profound ID may be more challenging compared to those with mild to moderate ID. Another explanation for differences in leisure participation is that individuals with severe to profound ID have a high level of support needs in their daily lives and are therefore have a greater degree of social dependence. They may therefore have less access to leisure activities and need support personnel to offer them appropriate activities. Another possible reason could be prejudice against individuals with severe to profound ID. Since they rarely communicate verbally or are sometimes completely non-verbal, some people may believe that they do not desire or need leisure activities and that therapy and care are sufficient. Since the social environment can also have a significant impact on leisure participation, our last hypothesis relates to this. Individuals with severe to profound intellectual disability often live in exclusive facilities and use services that are exclusively designed for people with disabilities. Perhaps they have no points of contact outside of these ‘special worlds’, and the social environment also wants to maintain the ‘protection’ of these exclusive worlds. Some studies have shown that the inclusive school setting and the community-based living situation (such as living with foster families or in the community with assistance) can influence leisure participation. [26,45,50]. As individuals with mild to moderate intellectual disabilities are more likely to be found in these settings than those with severe to profound intellectual disabilities [3], this may also explain the differences in leisure participation. It can be summarized that parents, staff, communities, institutions, policies, and people’s own choices influence each other’s participation in leisure activities in a multimodal way.

6.1. Perspectives for Practice and Further Research

This scoping review identifies opportunities for further research. First, most studies in this scoping review focused on describing patterns of participation. Few studies comprehensively examine a broad range of determinants of participation. Thus, there is a need for more studies that examine a range of personal, family, and environmental determinants of participation in leisure activities by people with ID across different activity types and settings. Further valid measurement instruments also need to be developed for this purpose. Future studies could focus on developing and/or adapting valid and standardized measurement instruments to survey leisure participation to provide robust measures and predictors of leisure participation among people with ID.

Second, most quantitative studies are cross-sectional in nature. It would be worth developing additional longitudinal studies that trace the development of leisure participation based on different determinants. Third, proxy surveys are still frequently found in both quantitative and qualitative studies. These fail to obtain the perspective of people with ID. Since the life domain of leisure in particular has a subjective interpretive authority, it is imperative that the people affected by a disability themselves have their voice heard.

The results further show that negative attitudes, separated ‘special’ services for people with ID, social support in the form of qualified and sensitized staff (e.g., to provide choice options), parents, and friends are important factors related to the level of participation in leisure. In addition, leisure is partly realized in the social space, in the community. Attention must be paid to the mobility of people with ID, access to offers, and information provided about offers without barriers. These factors require closer examination in the future. Studies on interventions, e.g., on the qualification of staff with regard to leisure assistance, on the promotion of leisure competencies of people with ID, and a reduction in these environmental barriers are also needed. Furthermore, our findings suggest that participation should be surveyed comprehensively, i.e., on subjective as well as objective aspects, and consider environmental barriers and facilitators.

Research indicates there are numerous possible pathways to promote participation in leisure time. Care providers, teachers, and families of children, youth, and adults with ID can work together to improve participation in leisure activities by addressing activity and environmental factors that have been shown to influence participation. Promoting participation must be multi-method and multi-modal [69]. Parents, teachers, and supporters can both promote leisure skills and shape contextual factors so that leisure participation can take place in social participation. Leisure competencies refer to a variety of knowledge, skills, and abilities that can contribute to experiencing leisure time in a subjectively satisfying way [70,71,72]. Parents, supporters, and assistants have the task of identifying a variety of leisure activities in society, offer these activities, and provide choices so that they may better recognize and support the leisure interests of people with ID. Leisure time is an area of life that is characterized by self-determined actions, choices, and decisions. Enabling this promotes individual development and a sense of self-efficacy.

In order for people with and without ID to be able to organize leisure time at all, the perception of free time represents an elementary basis. In the context of residential settings, schools, centers, and institutions, temporal, spatial, and visual structuring can help people with mild to moderate or severe to profound ID perceive free time, recognize leisure settings, and carry out leisure activities. To be able to experience leisure time in the community, not only are special offers for groups of people with ID needed, but inclusive leisure offers must be expanded and offered to a greater extent. To achieve this, a positive attitude towards inclusion in society is needed. Inclusive leisure activities can become possible if people with ID are involved as experts of their own lives in the planning and design of leisure activities by institutions. In addition, inclusion can be promoted when institutions for people with disabilities collaborate with other social institutions and leisure providers to plan activities together and break down barriers. Qualified staff is needed for this purpose. It also must be possible to travel to and enter the locations where leisure activities take place. Mobility concepts and barrier-free access to leisure locations are helpful for this purpose. When leisure providers make information available about their offerings, it is helpful for this information to be easily perceptible and comprehensible. Barrier-free equipment, adapted play concepts depending on the ability to act, and a positive attitude of those involved are supportive for experiencing leisure time positively in social participation in an inclusive community.

6.2. Limitations

The scoping review has the following limitations: gray literature was not included in the search, so some relevant information may be missing. Additionally, only English-language studies were searched in the databases. These were only included if they were accessible via an institutional login or were open access. The review focused exclusively on leisure participation, which excluded studies of leisure learning.

7. Conclusions

Knowledge about the participation of people with ID is incomplete and largely descriptive. Factors can be found that may have a positive or negative impact on leisure participation. Future studies could focus on testing a comprehensive model of the determinants of the participation of people with ID, incorporating environmental factors and statistical methods (e.g., structural equation modelling) to gain a better understanding of the different patterns of participation as a function of predictors. Practitioners and policymakers also need to consider specific determinants, such as attitudinal challenges and social support, to support social participation in the community.

Research points to several important environmental determinants. This allows for what could be a shift in practice from ‘fixing’ or ‘improving’ people with ID to changing and shaping the environment to enable and ensure participation in leisure time.

Author Contributions

Study conception, N.H., P.Z. and S.K.; methodology, N.H. and P.Z.; data collection and charting, N.H.; analysis and interpretation of results, N.H., P.Z. and S.K.; supervision, S.K. and P.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, N.H.; writing—review and editing: N.H., S.K. and P.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This publication was part of a practice research project in the field of inclusive youth work, which was funded by the Aktion Mensch Stiftung in Germany.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Study charting of the included studies.

Table A1.

Study charting of the included studies.

| Ref. | Authors | Sample and Diagnosis | Age (Year) | Type | Outcome Measures | Type of Leisure Participation | Main Findings (Pattern of Leisure Participation & Influencing Factors) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [60] | Beart; Hawkins; Kroese; Smithson; Tolosa 2001 UK | n = 29 (mild to moderate ID) | >16 | Qualitative | Focused interview (focus group) | Activities performed, facilitators to perform these activities, leisure wishes/interests, barriers to involvement | ‘It was found that participants undertook a wide variety of community-based leisure pursuits. Many of these activities took place in day centre time, as opposed to genuine leisure time. A range of activities which participants would wish to try in the future were identified. However, there were a number of perceived barriers which would make it difficult to access these opportunities. All five groups identified these barriers as being a lack of transport and carer/friend support.’ |

| [56] | Yu; Spevack; Hiebert; Martin; Goodman; Martin; Harapiak; Martin 2002 Canada | n = 12 (severe ID) n = 7 (profound ID) | 22–45 | Quantitative | Observation | Leisure activities for enjoyment: listening to music, watching TV, attending a concert in the gym, coffee and lunch breaks | ‘[…] groups showed more happiness indices during leisure than work activities, although the difference for the profound group was small (8% vs. 5%) compared to the severe group (18% vs. 4%).’ |

| [50] | Duvdevany; Arar 2004 Israel | n = 85 (ID) | 18–55 | Quantitative | Leisure Activities List [73], four further questionnaires (demographic, quality of life (QOL), loneliness, social relationship) | Subjective engagement (satisfaction, happiness, loneliness) during leisure activities, frequency of active and passive activities, and subjective assessment of independence | ‘The main findings show no significant differences between the two groups (people who live in foster homes and people who live in community settings) in the number of friendships or feelings of loneliness. Foster residents were more involved and more independent in their leisure activities than were those who live in community residences. […]’ |

| [58] | Wilson; Reid; Green 2006 USA | n = 3 (severe disabilities) | 25–29 | Quantitative | Interview (open-ended); structured interview; observations | Target behavior: participant leisure engagement in naturally occurring leisure times and responding to choices from the staff | ‘[…] during the choice presentation condition, each participant engaged in leisure activity during half or more of the observation intervals during each observation session […].’ ‘Corresponding with the lack of staff choice presentations during baseline, no participant was observed to make any leisure choices during baseline.’ ‘The comparison observations in other Supported Independent Living (SIL) situations further suggest that in-home leisure involvement of adults with severe disabilities can be problematic in these types of settings.’ |

| [28] | Buttimer; Tierney 2005 Ireland | n = 34 (mild/moderate ID) n = 34 (parents) | >16 | Quantitative | TLAB questionnaire [74] | Frequency of involvement in different kinds of activities (previous participation in a specific leisure activity and frequency); barriers of involvement | ‘Leisure activities which were mostly solitary and passive in nature were identified as those being most commonly engaged in. Barriers to leisure were also identified, with ‘access to’ and ‘location of’ the leisure facilities being barriers perceived by both students and parents.’ |

| [57] | Zijlstra; Vlaskamp 2005 Netherlands | n = 196 (PIMD) | >18 | Quantitative | Questionnaire, diary | Duration, frequency, location, and content of leisure activities in residential facilities during weekends | ‘A total mean of 3.8 h of leisure activities is provided for during the full weekend, almost half of which includes watching television or listening to music. Leisure activities are almost exclusively offered by professionals. Parents or volunteers only provide a minimum of activities during weekends.’ |

| [61] | Sellinger; Hodapp; Dykens 2006 USA | n = 223 (ID) | 5–54 | Quantitative | Behavior checklist, Leisure Activities Questionnaire [75] | Frequency of involvement in ‘common leisure activities for persons with mental retardation’ | ‘Individuals with Williams syndrome less often participated in visual-spatial activities, those with Prader-Willi syndrome more often performed both visual-spatial and visual strategy activities, and those with Williams and Down syndromes more often performed musical activities. With increasing chronological ages, all groups increased in their social activities […].’ |

| [51] | Yalon-Chamowitz; Weiss 2008 Israel | n = 33 (moderate ID & severe cerebral palsy) | 20–39 | Quantitative | Questionnaire adapted from short feedback questionnaire [76] and based on Witmer and Singer’s [77] presence questionnaire, structured observation | Subjective enjoyment of the game, the degree of success at it, the extent of control within game, concentration span and fatigue, as well as the degree of their involvement in choosing the game | ‘The VR-based activities were perceived by the participants to be enjoyable and successful. Moreover, participants demonstrated clear preferences, initiation and learning. They performed consistently and maintained a high level of interest throughout the intervention period.’ |

| [52] | Patterson; Pegg 2009 Australia | n = 10 (mild to moderate ID) | 19–57 | Qualitative | Semi-structured interviews | Participation in community-based serious leisure activities; questions about interest, importance, duration/frequency, friendship, belonging, barriers, enjoyment, goals for the future | ‘The results of this study found that people with disabilities have the ability to participate in serious leisure activities and to successfully engage at such a level so as to enable them to develop increased levels of confidence, skills and self-esteem.’ |

| [49] | Solish; Perry; Minnes 2010 Canada | n = 90 (Typically Developed children (TD)) n = 65 (Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)) n = 30 (ID) | 5–17 | Quantitative | The activities questionnaire (participation in social, recreational, leisure activities) | Number and frequency of social, recreational, and leisure activities with peers; leisure partners; number and nature of friendships | ‘The TD children participated in significantly more social and recreational activities and had more friends than the children with disabilities. […]’ Children with ASD or ID participated in more social activities with their parents or other adults than peers. Children with ID had more friends than children with ASD. |

| [62] | Azaiza; Rimmerman; Croitori; Naon 2011 Israel | n = 153 (ID) | 16–65 | Quantitative | Questionnaire | ‘Items assessing health condition, physical functioning, cognitive functioning, Activities of Daily Living and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (ADL & IADL), participation in employment and service utilisation’ | Employed participants participated more in leisure activities than unemployed participants. Cognitive functioning correlates strongly with participation in leisure activities. Physical functioning correlates weakly with participation in leisure activities. Participation in leisure activities correlated moderately with knowledge of services and accessibility to services. All the correlations were significant. |

| [26] | Badia; Orgaz; Verdugo; Ullán; Martínez 2011 Spain | N = 237 (DD) n = 161 (mild to moderate ID) n = 14 (severe ID) | 17–65 | Quantitatve | Leisure activity participation, preference, and interests (activity photographs), questionnaire (personal and disability-related factors) | Type and number of leisure activities and activities in which the individual would like to increase participation; degree of unmet leisure involvement based on the selection of activities in which the individual has an interest, but in which he or she is not participating; internal and external barriers for leisure participation | ‘The results show that participation in leisure activities is determined more by personal factors and perceived barriers than by disability-related factors.’ Perceived barriers accounted for the degree of participation in physical and social leisure activities. Participation in leisure activities at home were equally explained by personal and environmental factors. |

| [63] | Dusseljee; Rijken; Cardol; Curfs; Groenewegen 2011 Netherlands | n = 653 (mild or moderate ID) | 15–88 | Quantitative | Interviews and questionnaires of those who could not be interviewed | Community participation in the domains of work, social contacts, and leisure activities; assessment of participation in leisure activities by two items: ‘(1) whether the person with ID sometimes visited a restaurant, café, cinema or theatre; and (2) whether he/she was engaged in leisure activities not specifically for people with ID’ | ‘Most people with mild or moderate ID in the Netherlands have work or other daytime activities, have social contacts and have leisure activities. However, people aged 50 years and over and people with moderate ID participate less in these domains than those under 50 years and people with mild ID. Moreover, people with ID hardly participate in activities with people without ID.’ |

| [27] | Badia; Orgaz; Verdugo; Ullán 2013 Spain | N = 237 (DD) n= 167 (ID) | 17–65 | Quantitative | Leisure activity participation, preference and interests (activity photographs), questionnaire (personal and disability-related factors) | Actual performance of different types of leisure activities, wish to perform these activities more often, interest in participating in these activities | ‘Leisure social activities and recreation activities at home were mostly solitary and passive in nature and were identified as those being most commonly engaged in. Respondents expressed preference for more social and physical activity, and they were interested in trying out a large number of physical activities. Age and type of schooling determine participation in leisure activity. The results underscore the differences in leisure activity participation, preference and interest depending on the severity of the disability.’ |

| [23] | Badia; Orgaz; Verdugo; Ullán; Martínez 2013 Spain | N = 125 (ID) n = 52 (mild ID) n = 64 (moderate to severe ID) | 17–65 | Quantitative | The Spanish version of the Leisure Assessment Inventory (LAI) [26]: leisure activity participation, preference and interests (activity photographs), subjective scale of integral quality scale | Leisure participation dimensions are leisure activities, preference, interest, and constraints | ‘No relationship was found between objective quality of life and leisure participation. However, correlations between some leisure participation dimensions and specific subjective quality of life domains were observed. The results establish a predictive relationship between leisure participation and material, emotional, and physical well-being. […]’ |

| [46] | Dolva; Kleiven; Kollstad 2014 Norway | n = 38 (parents of adolescents with Down Syndrome) | 14 | Qualitative | Structured parent interviews | Focus on leisure activities that engage adolescents with Down syndrome in their everyday life outside school | ‘The adolescents’ leisure appears as active and social. However, social participation largely involved parents and family, while socializing with other adolescents mainly took place within formal activities adapted for disabled.’ |

| [64] | Dykens 2014 USA | n = 123 (parents of people with Prader-Willi Syndrome, mild ID) | 4–48 | Quantitative | Questionnaires (demographic variables, behavior), Recreation and Leisure Questionnaire [61], IQ test, semi-structured interview (adaptive behavior) | Frequency of engagement in 30 specific leisure activities, reasons for engagement | Watching TV was the most frequent recreational activity, and was associated with compulsivity and skin picking. BMIs were negatively correlated with physical play, and were highest in those who watched TV and played computer games. Computer games, puzzles, and physical activities were associated with a higher IQ and adaptive scores. |

| [53] | Lövgren; Bertilsdotter Rosqvist 2015 Sweden | n = 13 (ID) | 38–60 | Qualitative | Semi-structured interviews, field-visits | Everyday life, work vs. leisure, and retirement, ageing, and identity were highlighted | ‘Structured activities are arranged by disability services in order to normalise living conditions and provide recreation for disabled people. However, the range of activities is constrained by financial resources, by notions of gender and age and by an institutionalised emphasis on the work ethic—leading to constructions of leisure partly as ‘time beside’ where ‘free time’ activities should not interfere with the duties of the working week.’ ‘This ‘free time’ was mainly associated with household chores, exercise […] and some social activities. Media consumption was described as a common activity, and appeared to sometimes be a social activity but more commonly to be a way of dealing with loneliness.’ |

| [65] | Venkatesan; Vashodharakumar 2016 India | n = 90 (TD) n = 30 (ID) | 8–39 | Quantitative | Self-developed semi-structures demographic data sheet, survey | Leisure participation is operationalized as nature, types, content, spread, and extent of leisure activities; community exposure refers to areas of social activity which may be used or can become an opportunity included in an individual’s leisure pursuits | ‘Concurrently, opportunities for community exposure indicate an overall identical trend of limited social visits (Mean: 4.58; SD: 3.26) which is lowest for persons with intellectual disabilities (Mean: 1.33; SD: 1.3), followed by significantly higher frequency for those with visual impairments (Mean: 3.50; SD: 1.75), hearing loss (Mean: 4.00; SD: 2.27) and the typical group (Mean: 9.50; SD: 1.59).’ |