Thermal Analysis-Based Elucidation of the Phase Behavior in the HBTA:TOPO Binary System

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents

2.2. DSC Analysis

2.3. DES Solvent Extraction

3. Results and Discussion

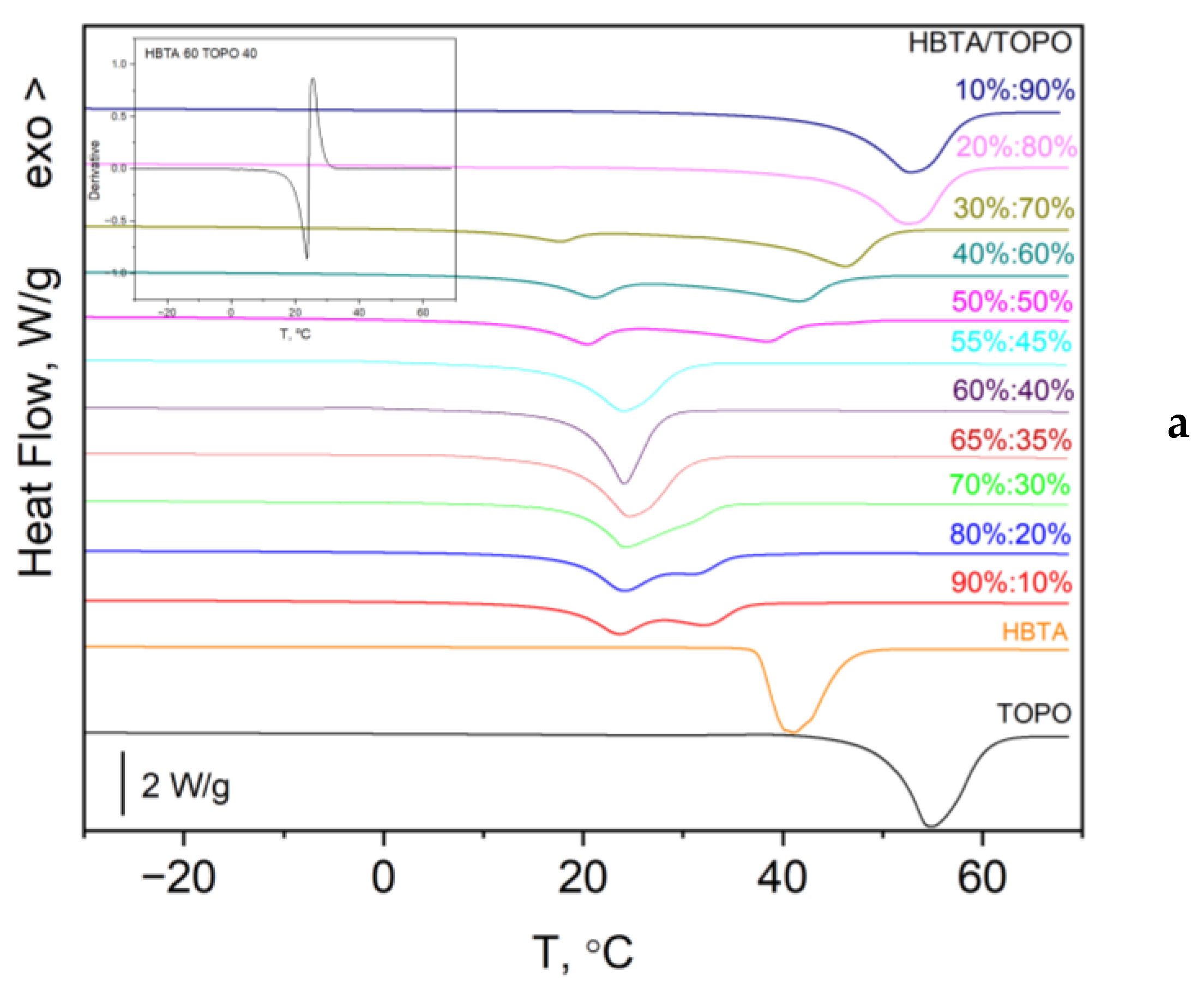

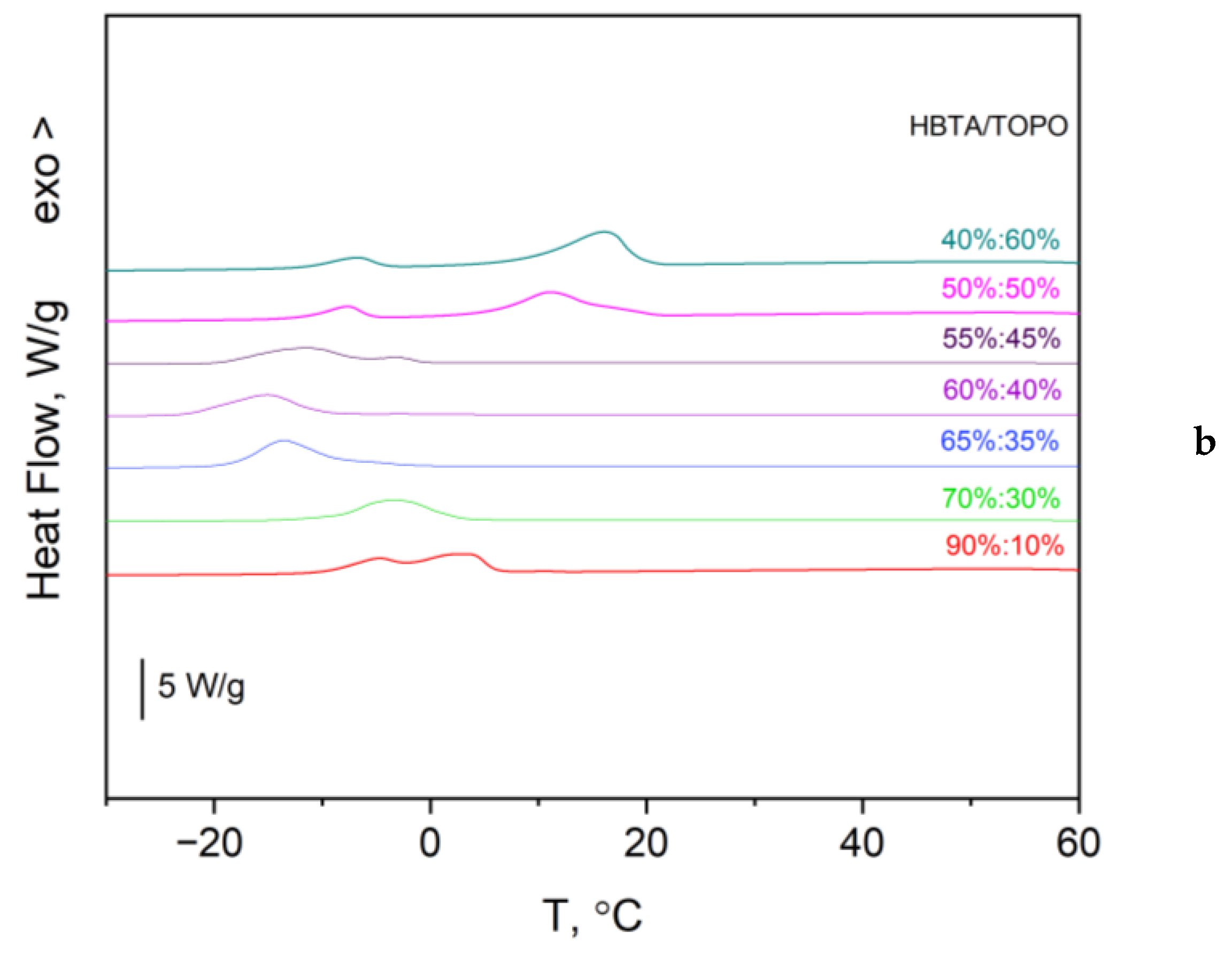

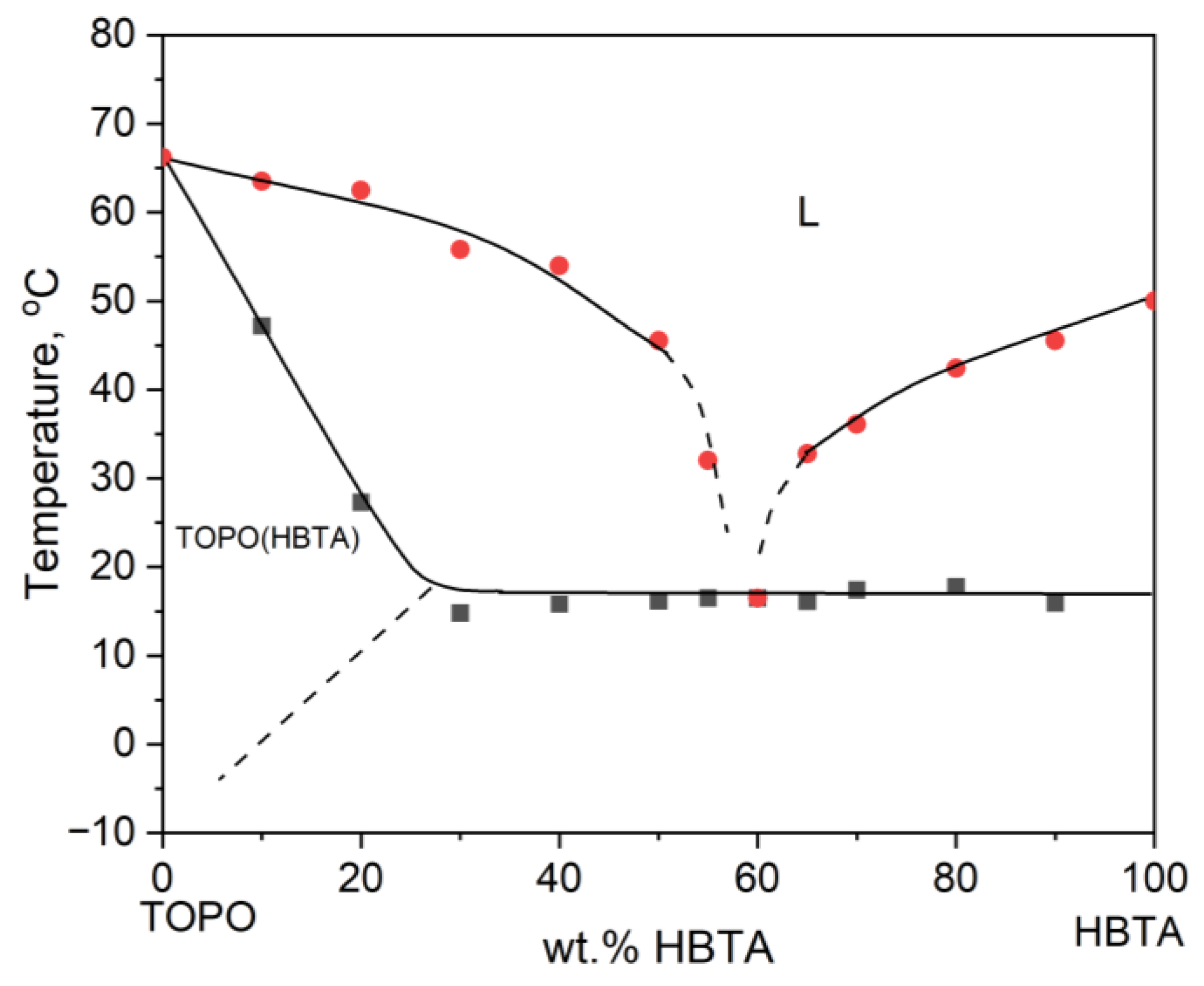

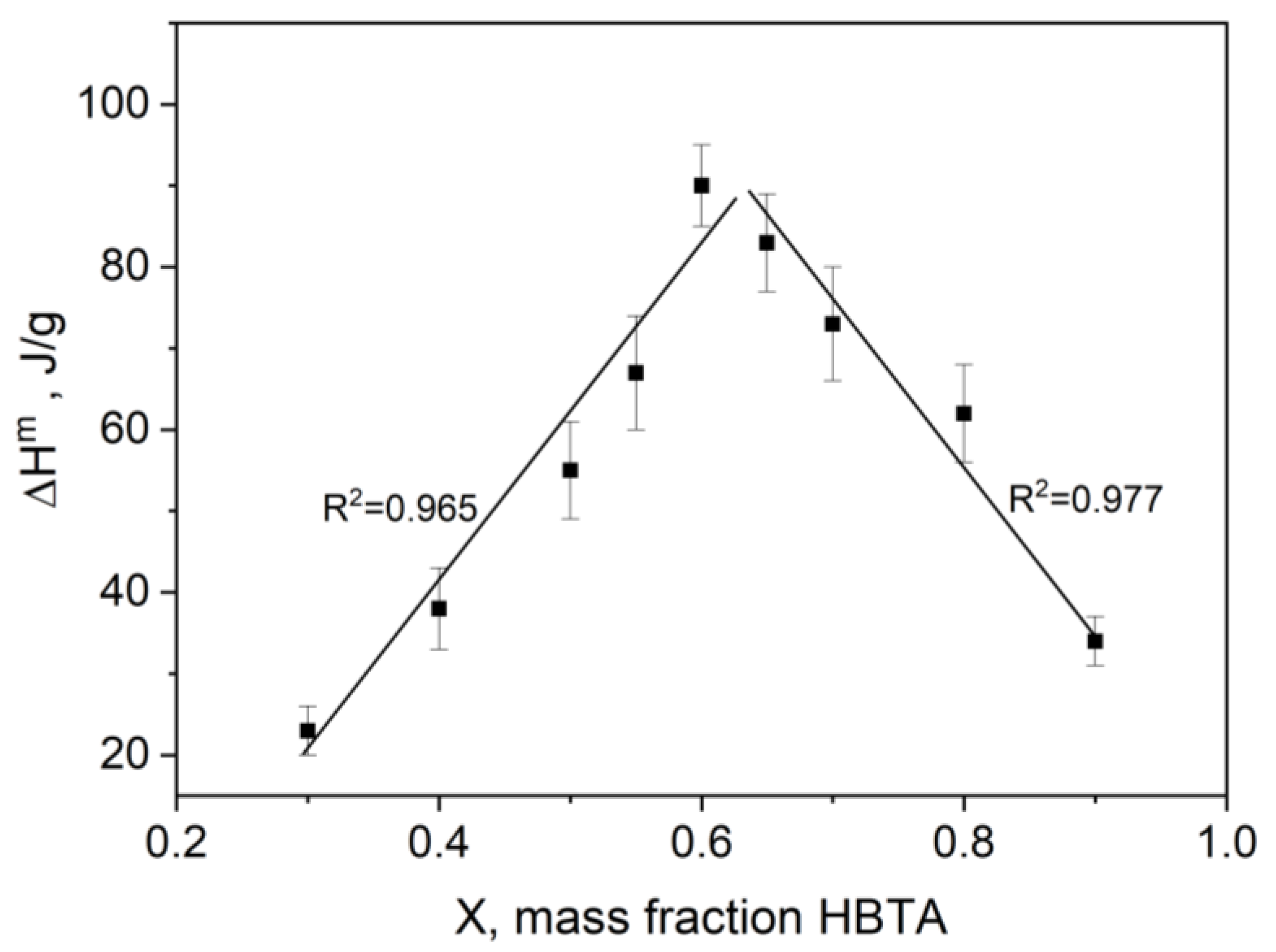

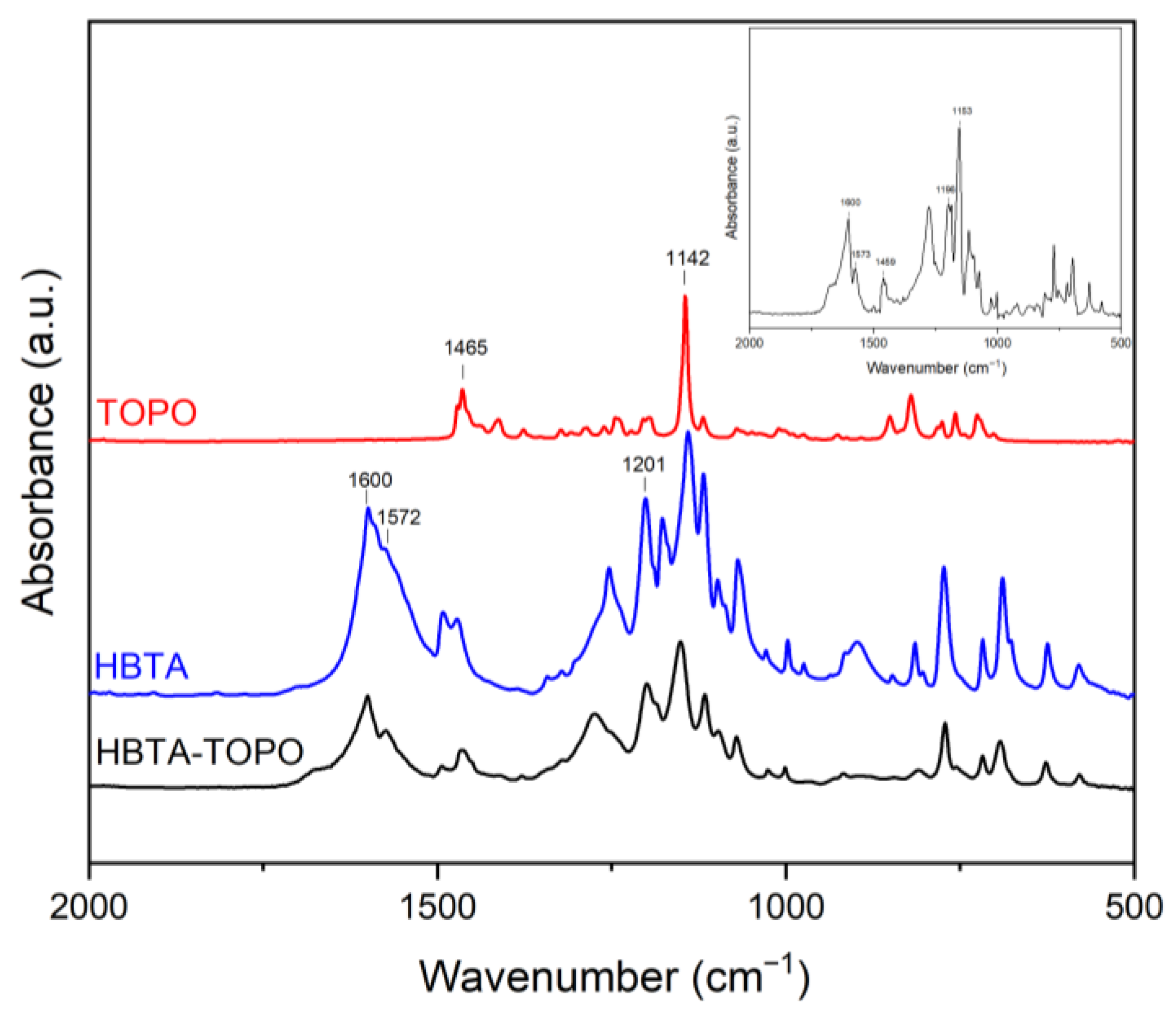

3.1. Thermal Analysis and Phase Behavior of the HBTA—TOPO Binary System

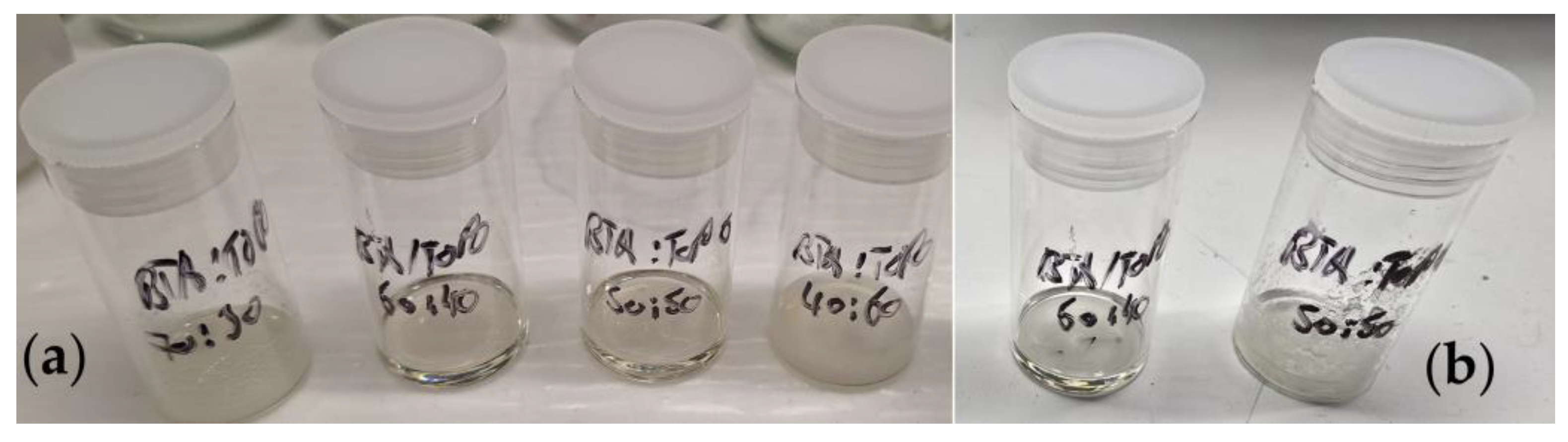

3.2. Li+ Extraction into the HBTA–TOPO DES

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abbott, A.P.; Capper, G.; Davies, D.L.; Rasheed, R.K.; Tambyrajah, V. Novel solvent properties of choline chloride/urea mixtures. Chem. Commun. 2003, 70–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, E.L.; Abbott, A.P.; Ryder, K.S. Deep eutectic solvents (dess) and their applications. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 11060–11082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sekharan, T.R.; Chandira, R.M.; Tamilvanan, S.; Rajesh, S.C.; Venkateswarlu, B.S. Deep eutectic solvents as an alternate to other harmful solvents. Biointerface Res. Appl. Chem. 2022, 12, 847–860. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; De Oliveira Vigier, K.; Royer, S.; Jérôme, F. Deep eutectic solvents: Syntheses, properties and applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 7108–7146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padinhattath, S.P.; Shaibuna, M.; Gardas, R.L. Solvent extraction with hydrophobic deep eutectic solvents: A benign alternative for efficient industrial wastewater treatment. In Deep Eutectic Solvents; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, USA, 2025; Volume 1504, pp. 271–290. [Google Scholar]

- Paiva, A.; Craveiro, R.; Aroso, I.; Martins, M.; Reis, R.L.; Duarte, A.R.C. Natural deep eutectic solvents—Solvents for the 21st century. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2014, 2, 1063–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, M.; García-Díaz, I.; López, F. Properties and perspective of using deep eutectic solvents for hydrometallurgy metal recovery. Miner. Eng. 2023, 203, 108306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Kim, J.; Lee, J.; Yang, H.; Jo, S.; Choi, W.; Kim, J.; Hong, H. Research trends in rare metal recovery processes using deep eutectic solvents. Korean J. Met. Mater. 2025, 63, 651–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alguacil, F. Utilizing deep eutectic solvents in the recycle, recovery, purification and miscellaneous uses of rare earth elements. Molecules 2024, 29, 1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, K.; Fan, D.; Wang, X.; Dong, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Cui, P.; Meng, F.; Wang, Y.; Qi, J. Lithium extraction from aqueous medium using hydrophobic deep eutectic solvents. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 110490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanada, T.; Goto, M. Synergistic deep eutectic solvents for lithium extraction. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 2152–2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodenough, J.B.; Park, K.S. The li-ion rechargeable battery: A perspective. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 1167–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, G.; Rentsch, L.; Höck, M.; Bertau, M. Lithium market research—Global supply, future demand and price development. Energy Storage Mater. 2017, 6, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanagasundaram, T.; Murphy, O.; Haji, M.N.; Wilson, J.J. The recovery and separation of lithium by using solvent extraction methods. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2024, 509, 215727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Wang, Y.; Chen, L.; Duan, W.; Ren, Z.; Zhou, Z. Ionic liquid for selective extraction of lithium ions from tibetan salt lake brine with high na/li ratio. Desalination 2024, 574, 117274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, L.; Rui, H.; Shi, D.; Peng, X.; Ji, L.; Song, X. Lithium recovery from effluent of spent lithium battery recycling process using solvent extraction. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 398, 122840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, L.; Shi, D.; Li, J.; Peng, X.; Nie, F. Selective extraction of lithium from alkaline brine using hbta-topo synergistic extraction system. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2017, 188, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, L.; Shi, D.; Peng, X.; Song, F.; Nie, F.; Han, W. Recovery of lithium from alkaline brine by solvent extraction with β-diketone. Hydrometallurgy 2018, 175, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, C.; Liu, C.; Han, Z.; Wang, J.; Liang, Y.; Zhong, H.; He, Z. Sustainable and efficient recovery of lithium from rubidium raffinate via solvent extraction. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 113374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masmoudi, A.; Zante, G.; Trébouet, D.; Barillon, R.; Boltoeva, M. Solvent extraction of lithium ions using benzoyltrifluoroacetone in new solvents. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2021, 255, 117653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Septioga, K.; Fajar, A.T.N.; Wakabayashi, R.; Goto, M. Deep eutectic solvent-aqueous two-phase leaching system for direct separation of lithium and critical metals. ACS Sustain. Resour. Manag. 2024, 1, 2482–2491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, J.; Ji, L.; Li, L. Separation of lithium from alkaline solutions with hydrophobic deep eutectic solvents based on β-diketone. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 344, 117729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croft, C.F.; Sarafska, T.; Spassov, T.G.; Kolev, S.D. Development of a polymer inclusion film incorporating a 1-dodecanol-decanoic acid eutectic mixture for the extraction of dy3+ and y3+. React. Funct. Polym. 2025, 216, 106454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Tu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Hu, X.; Wu, Y. Acidic protic ionic liquid-based deep eutectic solvents capturing SO2 with low enthalpy changes. AIChE J. 2023, 69, e18145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trombino, S.; Siciliano, C.; Procopio, D.; Curcio, F.; Laganà, A.S.; Di Gioia, M.L.; Cassano, R. Deep eutectic solvents for improving the solubilization and delivery of dapsone. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Las Heras, I.; Dufour, J.; Coto, B. A novel method to obtain solid–liquid equilibrium and eutectic points for hydrocarbon mixtures by using differential scanning calorimetry and numerical integration. Fuel 2021, 297, 120788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craveiro, R.; Aroso, I.; Flammia, V.; Carvalho, T.; Viciosa, M.T.; Dionísio, M.; Barreiros, S.; Reis, R.L.; Duarte, A.R.C.; Paiva, A. Properties and thermal behavior of natural deep eutectic solvents. J. Mol. Liq. 2016, 215, 534–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhadid, A.; Nasrallah, S.; Mokrushina, L.; Minceva, M. Design of Deep Eutectic Systems: Plastic Crystalline Materials as Constituents. Molecules 2022, 27, 6210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schawe, J.E.K.; Höhne, G.W.H. The analysis of temperature modulated dsc measurements by means of the linear response theory. Thermochim. Acta 1996, 287, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Imrie, C.T.; Hutchinson, J.M. An introduction to temperature modulated differential scanning calorimetry (tmdsc): A relatively non-mathematical approach. Thermochim. Acta 2002, 387, 75–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schawe, J.E.K. A comparison of different evaluation methods in modulated temperature dsc. Thermochim. Acta 1995, 260, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Findlay, A. The Phase Rule and Its Applications; Longmans, Green, and Company: London, UK, 1911. [Google Scholar]

- Guenet, J.-M. Contributions of phase diagrams to the understanding of organized polymer-solvent systems. Thermochim. Acta 1996, 284, 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rycerz, L. Practical remarks concerning phase diagrams determination on the basis of differential scanning calorimetry measurements. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2013, 113, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Composition HBTA:TOPO, Mass % | 90:10 | 80:20 | 70:30 | 65:35 | 60:40 | 55:45 | 50:50 | 40:60 | 30:70 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔHeut, J/g | 34 ± 3 | 62 ± 6 | 73 ± 7 | 83 ± 6 | 90 ± 5 | 67 ± 7 | 55 ± 6 | 38 ± 5 | 23 ± 3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ivanova, S.; Croft, C.F.; Sarafska, T.; Smith, J.N.; Kukoc, L.; Kolev, S.D.; Spassov, T.G. Thermal Analysis-Based Elucidation of the Phase Behavior in the HBTA:TOPO Binary System. Thermo 2026, 6, 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/thermo6010009

Ivanova S, Croft CF, Sarafska T, Smith JN, Kukoc L, Kolev SD, Spassov TG. Thermal Analysis-Based Elucidation of the Phase Behavior in the HBTA:TOPO Binary System. Thermo. 2026; 6(1):9. https://doi.org/10.3390/thermo6010009

Chicago/Turabian StyleIvanova, Stanislava, Charles F. Croft, Tsveta Sarafska, James N. Smith, Lea Kukoc, Spas D. Kolev, and Tony G. Spassov. 2026. "Thermal Analysis-Based Elucidation of the Phase Behavior in the HBTA:TOPO Binary System" Thermo 6, no. 1: 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/thermo6010009

APA StyleIvanova, S., Croft, C. F., Sarafska, T., Smith, J. N., Kukoc, L., Kolev, S. D., & Spassov, T. G. (2026). Thermal Analysis-Based Elucidation of the Phase Behavior in the HBTA:TOPO Binary System. Thermo, 6(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/thermo6010009