Abstract

Using boundary-layer theory, natural convection heat transfer formulas that are accurate over a wide range of Rayleigh numbers (Ra) were developed in the 1970s and 1980s for vertical and downward-facing plates. A comprehensive formula for upward-facing plates remained unsolved because they do not form conventional boundary-layers. From the thermodynamic constraints on heat-engine efficiency, the novel approach presented here derives formulas for natural convection heat transfer from isothermal plates. The union of four peer-reviewed data-sets spanning has 5.4% root-mean-squared relative error (RMSRE) from the new upward-facing heat transfer formula. Applied to downward-facing plates, this novel approach outperforms the Schulenberg (1985) formula’s 4.6% RMSRE with 3.8% on four peer-reviewed data-sets spanning . The introduction of the harmonic mean as the characteristic length metric for vertical and downward-facing plates extends those rectangular plate formulas to other convex shapes, achieving 3.8% RMSRE on vertical disk convection from Hassani and Hollands (1987) and 3.2% from Kobus and Wedekind (1995).

1. Introduction

Natural convection is the flow caused by nonuniform density in a fluid. It is a fundamental process with applications from engineering to geophysics.

When a stationary, immersed object changes temperature, nearby fluid can change density as it warms or cools. Under the influence of gravity, density changes cause fluid to flow. The rates of fluid flow and heat transfer from the object grow until reaching a plateau. This investigation seeks to predict the overall steady-state heat transfer rate from an external, flat, isothermal surface inclined at any angle in a Newtonian fluid.

An “external” plate is one that fluid can flow around freely, especially horizontally. If enclosed, the enclosure must have dimensions much larger than the heated or cooled surface. Natural convection in an enclosure of size comparable to the heated or cooled surface can organize into cells of Rayleigh-Bénard convection, which is not treated here.

The characteristic length L is the length scale of a physical system. For many heat transfer processes, it is the volume-to-surface-area or area-to-perimeter ratio of the heated or cooled object. There are several characteristic length metrics used for natural convection, some of which are valid only for convex objects. This investigation focuses on flat plates with convex perimeters.

1.1. Flow Topologies

There are three topologies of convective flow from external, convex plates.

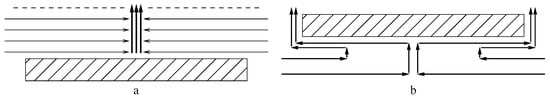

For a horizontal plate with a heated upper face, streamline photographs in Fujii and Imura [1] show natural convection pulling fluid horizontally from above the plate’s perimeter into a rising central plume. Figure 1a, below, is a diagram of this upward-facing convection. Horizontal flow is nearly absent at the elevation of the dashed line.

Figure 1.

(a) flow above a heated plate; (b) flow below a heated plate.

Kitamura, Mitsuishi, Suzuki, and Kimura [2] show top-views of plumes from heated rectangular plates with aspect ratios between 1:1 and 8:1. The plates with high aspect ratios have a plume over the plate’s mid-line parallel to the longer sides, but not as long.

The streamline photograph of a vertical plate in Fujii and Imura [1] shows fluid being pulled horizontally before rising into a plume along the vertical plate.

Modeled on a streamline photograph in Aihara, Yamada, and Endö [3], Figure 1b is a flow diagram for a horizontal plate with heated lower face. Unheated fluid below the plate flows horizontally inward. It rises a short distance, flows outward closely below the plate, and flows upward upon reaching the plate edge.

There is a symmetry in external natural convection; a cooled plate induces downward flow instead of upward flow. Flow from a cooled upper face is the mirror image of flow from a heated lower face. Flow from a cooled lower face is the mirror image of flow from a heated upper face.

Sublimation from an upper face is downward convection when the dissolved sublimate is denser than the fluid. The rest of this investigation assumes a heated plate.

An important aspect of all three flow topologies is that fluid is pulled horizontally before being heated by the plate. Pulling horizontally expends less energy than pulling vertically because the latter does work against the gravitational force. Inadequate horizontal clearance around a plate can obstruct flow and reduce convection and heat transfer.

1.2. Fluid Mechanics

In fluid mechanics, the convective heat transfer rate is represented by the average Nusselt number (). The Rayleigh number () is the impetus to flow due to temperature difference and gravity. A fluid’s Prandtl number () is its momentum diffusivity per thermal diffusivity ratio. These three “variable groups” are dimensionless (measurement units of the constituent variables cancel each other).

The characteristic length L scales ; is scaled by ; is independent of L.

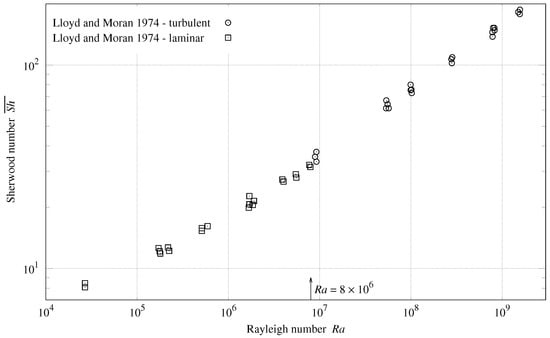

Formulas for heat transfer can apply to mass transfer via analogous variable groups, such as Schmidt number () and . Figure 2 has Sherwood number () instead of on its vertical axis.

Figure 2.

Upward convection mass transfer from horizontal plate.

1.3. Turbulence Versus Laminar Flow

Previous investigations [1,2,4,5] assumed that natural convection heat transfer formulas would differ substantially when the convection was turbulent versus laminar. For their upward-facing plate, Lloyd and Moran [4] reported that the transition from laminar to turbulent flow occurred at . The straight line segments they fitted to their data at greater and lesser were disjoint at . However, with their fit lines removed, if represents a discontinuity, then it is one of several, and subsumed within the scatter of their measurements in Figure 2.

About their measurements of vertical and downward tilted plates, Fujii and Imura [1] wrote:

“Though the boundary layer was not always laminar near the trailing edge for large [] values, no influence of the flow regime on the data shown …is appreciable.”

Churchill and Chu [5] conclude that one of its equations

“…based on the model of Churchill and Usagi [6] provides a good representation for [sic] the mean heat transfer for free convection from an isothermal vertical plate over a complete range of Ra and Pr from 0 to ∞ even though it fails to indicate a discrete transition from laminar to turbulent flow.”

The lack of a significant transition between the rates of (mean) heat transfer in laminar and turbulent natural convection indicates that a more basic principle organizes natural convection.

1.4. Thermodynamics

The fundamental laws of thermodynamics make no distinction between laminar and turbulent flows. Considering a small object inside a very tall column of fluid as a closed system, natural convection is a heat engine that converts the temperature difference between the object and fluid into the flow of that fluid. The heated object is the heat source; fluid far above the object is the heat sink.

System-wide thermodynamic constraints cannot be enforced locally, requiring a radical departure from boundary-layer analysis (which is based on local flow solutions of the Navier–Stokes equations). This investigation solves algebraic equations in terms of average fluid velocity, heat conduction, and power flux.

1.5. Not Empirical

Empirical theories derive their coefficients from measurements, inheriting the uncertainties from those measurements. Theories developed from first principles derive their coefficients mathematically. For example, the Blasius model of laminar flow coefficient is the solution of a differential equation (Lienhard and Lienhard [7]). Another example is the heat conduction shape factor for one face of a disk, which is exactly twice its diameter. The present theory derives from first principles; it is not empirical. (The conduction shape factor is used in Section 8. It is derived exactly in Section 16.) Each equation term is tied to an aspect of the plate geometry, orientation, and flow diagram.

This investigation tests its theory on prior works’ measurement data with as wide a range of and as possible. Few of the cited studies provided estimated measurement uncertainties. Root-mean-squared relative error (RMSRE), introduced in Section 7.5, provides an objective, quantitative evaluation of each data set versus the theory.

1.6. Detail

Were this theory derived using the usual fluid-mechanics techniques, derivation detail would be unnecessary. However, this powerful new methodology is unlike those techniques. The first derivations provide more detail to enable readers to adapt the present methodology to other fluid mechanics problems.

2. Materials and Methods

There are robust measurements of natural convection heat and mass transfer in the peer-reviewed literature. Table 1 lists the data-sets to be compared with the present theory. Within each face group, all have been scaled to the same characteristic length metric. The “±” column is the estimated convection measurement uncertainty (scatter from Lloyd and Moran [4]) reported in the cited source. Both plates from Fujii and Imura [1] had side walls.

Table 1.

Sources of measurements.

Measurements were copied from the text of Aihara et al. [3], Faw and Dullforce [10], and Goldstein and Lau [11]. The remaining heat transfer measurements were captured from graphs in the cited works by measuring the distance from each point to its graph’s axes, then scaling to the graph’s units using the “Engauge” software. Measurements obscured by other points in the graph were excluded. (Excluding the obscured points eliminates clustered points, not outliers; thus, correlations with theory will tend to be weaker than if all the points had been included.)

These data files, which were used for generating the present work graphs and tables, are collected in Supplementary Material.

3. Prior Work

3.1. Atmospheric Science

Rennó and Ingersoll [12] relate the “convective available potential energy” (CAPE) of a planetary atmosphere to heat-engine efficiency. Atmospheric convection is analyzed as a four-phase cyclic heat engine. They introduce “total convective available potential energy” (TCAPE) in terms of the reversible heat-engine efficiency limit . For dry air:

where is the fluid’s specific heat (at constant pressure), T is the absolute temperature of the ground (heat source), and is the upper atmosphere (heat sink) absolute temperature.

, where is the heat-engine efficiency of natural convection. Rennó and Ingersoll assert that . Thus, .

The Goody [13] cyclic heat-engine analysis splits atmospheric convection into four phases, three of them reversible, and accounts for their energy flows and entropy. Table 2 shows the sink () and source (T) temperatures, the efficiency limits from Goody (), and . In the first row, matches within . In the second row, is 30% larger than . The third row changes from 260 K to 250 K, causing and to match within 1%. If “260 K” was a misprint, then both studies agree that .

Table 2.

Atmospheric convection efficiency limit.

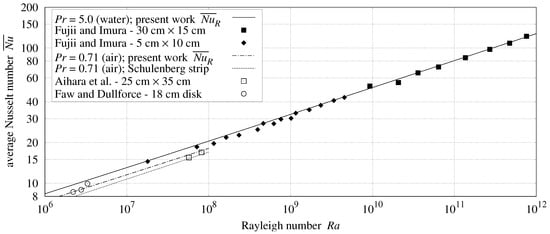

3.2. Upward Natural Convection from a Horizontal Plate

For upward convection heat or mass transfer from a horizontal surface, prior works [1,2,4,8,11] propose constant coefficients fitted to fractional powers of , spanning various ranges. The goal of this investigation being a comprehensive formula, the present theory will be compared with the measurements presented in these works, not with their piece-wise power-law approximations.

3.3. Natural Convection from a Vertical Plate

The natural convection heat transfer formula developed by Churchill and Chu [5] for a vertical rectangular isothermal plate is:

3.4. Downward Natural Convection from a Horizontal Plate

Schulenberg [14] derives a formula for convection below a level isothermal strip of width . The Schulenberg [14] heat transfer formula for an isothermal strip was:

1.156 is the only 4-digit coefficient in the paper’s isothermal plate correlations; the others have 3 significant digits. Section 11 graphically demonstrates the discrepancy.

Proposed is a corrected formula and its equivalent, normalized so that appears only in the denominator:

Schulenberg also gives a formula for downward convection from a level isothermal disk using its radius as the characteristic length. The expression on the right side is its equivalent normalized form:

4. Unenclosed Heat Engine

Although most textbook heat-engine analyses are of cyclic heat engines, a continuous process can also convert a temperature difference into mechanical work, which qualifies it as a heat engine.

Consider a large vertical column of still, dry air having a molar mass M under the influence of gravitational acceleration g. Initially, the air will be in equilibrium, with uniform absolute temperature and a pressure profile P which decays exponentially with altitude z:

where is the universal gas constant, the ideal gas law finds the density of a parcel of air:

A heated parcel of volume V has a density of . The buoyancy force on it is:

Given , is the heat required to raise the parcel temperature from to . The force on the parcel is:

As it rises, the parcel’s state changes. Temperature, volume, and pressure are three variables having two degrees of freedom from Formula (7). For a large vertical column of still, dry air, Fermi [15] teaches:

Since air is a poor conductor of heat, very little heat is transferred to or from the expanding air, so that we may consider the expansion as taking place adiabatically.

Hence, the temperature of a parcel of dry air drops per kilometer of altitude gain. In a column having initially uniform temperature, a heated parcel will rise until its temperature drops to .

From the conservation of mass, , where and are the density and volume at altitude . The maximum work W which can be extracted from a buoyant parcel is the integral of upward force Formula (9) with respect to altitude z above the heated plate:

The thermodynamic efficiency () of this ideal convection heat engine will be the thermodynamic efficiency limit for external convection, :

Note that is of the (Carnot) reversible heat-engine efficiency limit .

This derivation was for adiabatic gases whose coefficient of thermal expansion . More generally:

The system being in continuous operation, instead of energies W and , power fluxes () are of interest. The powers per heated plate area are for the kinetic flux of the fluid and for the plate total, which is also the convective power flux. The thermodynamic efficiency of a steady-state convection process is , which the second law of thermodynamics constrains so that:

5. Dimensional Analysis

Additional fluid properties used in this investigation are thermal conductivity k, kinematic viscosity , and thermal diffusivity . is the average convective surface conductance, with units .

“Scalable” heat transfer equations are relations between named, dimensionless “variable groups”, which themselves are functions of variables and other variable groups. “Dimensional analysis” discovers these dimensionless variable groups and their scalable relationships.

Nusselt’s dimensional analysis of natural convection (from Lienhard and Lienhard [7]) employs four variable groups: average Nusselt number , Prandtl number , , and .

The equivalence was added for this investigation.

From these variable groups come the dimensionless Grashof number () and Rayleigh number ():

Let be the heat transport capacity per kinetic energy ratio. increases with , g, L, and :

The denominator , canceling one of the two factors of in , makes dimensionless.

Two variable groups with power flux units () will prove useful:

6. Combining Heat Transfers

Conduction and convection are both heat transfer processes.

There is an unnamed form that appears frequently in heat transfer formulas:

Churchill and Usagi [6] wrote that such formulas are “remarkably successful in correlating rates of transfer for processes which vary uniformly between these limiting cases.”

A value of models competitive processes; the combined transfer rate is between the larger constituent rate and their sum.

models independent processes; the combined transfer rate is the sum of the constituent rates.

The Churchill and Chu Formula (2) for vertical plates has the form of Equation (19) with . Natural convection requires some conduction to heat the fluid. This is consistent with cooperating processes having ; when both are transferring, the combination is larger than their sum.

With and , taking the pth root of both sides of Equation (19) yields a vector-space functional form known as the -norm, which is notated :

7. Upward-Facing Circular Plate

7.1. Characteristic Length

For a horizontal upward-facing plate, Figure 1a shows that natural convection pulls fluid from the edges into a central plume. The characteristic length should be a function of radial distance from the edges to the center. This is accomplished by using the area-to-perimeter ratio as the characteristic length L.

Lloyd and Moran [4] measured upward convection from horizontal disks, rectangles, and right triangles having aspect ratios between 1:1 and 10:1. They wrote:

It is immediately obvious that within the scatter of the data, approximately percent, the data from all plan-forms are correlated through the use of , …

Goldstein et al. [8] found that correlated their measurements with aspect ratios between 1:1 and 7:1.

7.2. Conduction

Consider a horizontal disk with its upper face, having area A, heated to . Its is of its radius. The power flowing from an object into a stationary, uniform medium is , where k is thermal conductivity and S is the conduction shape factor (having length unit). For one side of a disk, Incropera, DeWitt, Bergman, and Lavine [16] gives . Converting conduction power flux into conduction Nusselt number from Formula (14):

7.3. Kinetic Flux

Fluid heated near the plate converts thermal energy into kinetic energy by accelerating upward. Fluid accelerating upward spreads apart, pulling fluid horizontally to maintain its density. At some elevation , the fluid no longer accelerates upward (otherwise, its velocity would be unbounded) and the horizontal flow is negligible, which is marked by the dashed line in Figure 1a.

An ideal turbine at elevation would capture the upward kinetic energy of the plume. The kinetic power through the aperture would be , where u is the plume upward velocity; its flux, .

Vertical acceleration pulls fluid horizontally at elevations between 0 and . “Fig. 14(f)” of Fujii and Imura [1] shows that horizontal velocities are fairly uniform within that span. The kinetic flux should be proportional to scaled by . grows with u, but shrinks with kinematic viscosity because of viscous losses. has reciprocal length units, while already has power flux units. This suggests scaling by a (dimensionless) Reynolds number , which is used extensively for modeling forced flows. Let , where is the average length of flow parallel to the plate. For the upward-facing plate, ; hence , leading to a kinetic power flux . From the dimensional analysis, is the maximum heat flux which could be transported by the flow induced by u. Multiplying this heat flux by yields the maximum kinetic flux which could result from natural convection:

7.4. Plate Flux

With upward convection pulling fluid horizontally from the disk’s perimeter, heat transfer near the perimeter is more flow-induced than it is conduction. If the flow were parallel, 1/2 of the plate’s area would be considered flow-induced. If the flow were radial, would be considered flow-induced. However, the square plate photographs in Kitamura et al. [2] show plumes as a network of connected ridge segments, not a central cone. An intermediate allocation is needed. The geometric mean of and is . Hence, of the plate is designated as flow-induced, of the plate as conduction.

Heat transfer from the flow-induced part of the plate will be proportional to , , and Formula (22) u in the dimensionless expression . As cooperating processes, conductive and flow-induced heat transfers combine using the -norm. Solving for plate power flux from Formula (14):

Assume , so that the term can be ignored. From definitions (18) collect and terms:

Dividing both sides of Formula (25) by , then raising both sides to the 4/3 power, isolates :

In the absence of obstruction, and will increase to the maximum allowed by upper-bound Formula (26). Substituting from Formula (26) into Formula (24) yields the asymptotic formula for plate flux :

Restoring the -norm from Equation (23) into Equation (29) yields the comprehensive formula for natural convection heat transfer from an external, horizontal plate’s isothermal upper face:

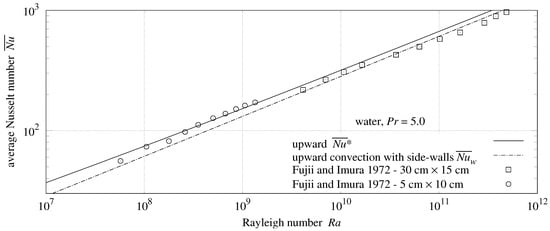

7.5. Upward-Facing Measurements

Formula (30) assumes unobstructed flow. A completely unobstructed apparatus is difficult to build. Measurements smaller than are expected.

Measurement bias and uncertainty can result in values slightly larger than .

Lloyd and Moran [4] estimated 5% scatter for their data. Two “Lloyd and Moran 1974—laminar” points at 26,900 have values of 14% and 19% larger than in Figure 3.

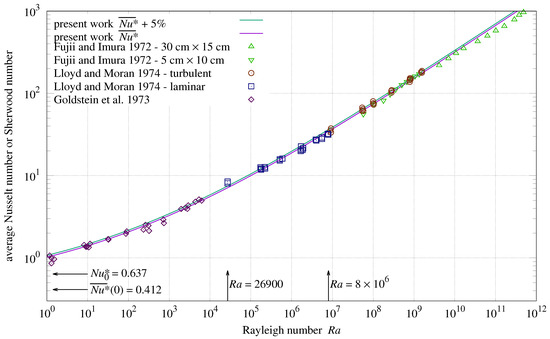

Figure 3.

Upward convection heat or mass transfer from horizontal plate.

26,900 was the smallest measured by Lloyd and Moran; the next smallest 171,750 was 6.4 times larger. Range extremes are often the most susceptible to measurement bias. Having excesses several times larger than 5%, the points at 26,900 should be excluded as outliers.

Excluding the two largest and two smallest measurements relative to , the Lloyd and Moran measurements have a 4.9% root-mean-squared relative error (RMSRE) from . This is a close match spanning four orders of magnitude of which includes the laminar-turbulent transition at .

7.6. RMSRE

RMSRE gauges the fit of measurements to formula , giving each measurement equal weight. The root-mean-squared error of relative to at n points is:

Table 3 also splits RMSRE into bias and scatter. The root-sum-squared of bias and scatter is RMSRE.

Table 3.

Upward convection mass or heat transfer from horizontal plate.

Note that in Figure 3. models convection; it does not extend to static conduction.

The Fujii and Imura upward-facing data-set is revisited in Section 20.

8. Vertical Rectangular Plate

8.1. Characteristic Length and Conduction

The vertical characteristic length is the plate’s height. The conduction constant will not depend on the plate’s width. The asymptotic case is a strip, an infinitely wide rectangle.

Conduction shape factors are not well-defined with unbounded source areas, but Nusselt numbers can be. Fortunately, for a strip can be related to square plate . Incropera et al. [16] give a dimensionless shape factor for both faces of a rectangular plate. For one face of an square plate:

Strip conduction must distribute over one dimension (vertical) what square plate conduction distributes over two:

8.2. Kinetic and Plate Fluxes

Fluid is pulled horizontally before rising into a plume at the plate. The upward flow is parallel; the plate area is treated as 1/2 flow-induced, 1/2 conduction. The average length of contact with the plate is , resulting in the factor . Fluid heated by the plate accelerates upward along its surface. This reduces the effective length of contact by 1/2, resulting in as the heat transfer factor in Formula (36). The kinetic and plate power fluxes are:

Assume and ignore the conduction term; collect and terms from definitions (18):

Dividing both sides of Formula (38) by , then raising both sides to the 4/3 power, isolates :

Reintroduce the -norm into Formula (41):

For large , the Churchill and Chu Equation (2) reduces to .

9. Downward-Facing Rectangular Plate

Figure 1b shows flow in two plumes on horizontally opposite sides of the plate; downward-facing characteristic length is of the shorter plate edge. Compared with the vertical convection strip, and . Plate areas are treated as 1/2 flow-induced, 1/2 conduction.

For upward-facing and vertical plates, the induced flow brings unheated fluid into contact with the plate, which is responsible for amplifying convection. In contrast, fluid below the downward-facing plate is warmed by conduction through the fluid above it. The outward creep immediately below the plate stays in contact until it reaches a plate edge. The fluid’s temperature profile differs little from static conduction. Thus, static and dynamic heat transfers are combined using the -norm, which is addition.

Figure 1b shows convective flow experiencing three changes in direction. Two horizontal accelerations and decelerations of flow introduce two factors of into . The short upward acceleration and deceleration of flow below the plate is the only such occurrence among the three plate orientations. It slightly opposes buoyant flow because fluid immediately below the plate is less dense than fluid moving upward to replace it. There is no appropriate vertical distance, is used for the third factor in .

All of the lower face is in contact with the horizontal flow; the heat transfer factor is :

Assume and ignore the conduction term; collect and terms; then solve for plate flux :

The plate obstructs heated fluid from rising; thus, will be an upper-bound. Solving for in Equation (45), restoring the -norm (addition), and substituting for :

10. Generalization

These three derivations can be generalized to Equation (48) via Formula (47). L is characteristic length; is static conduction; E is the count of changes in direction of fluid flow; B is the sum of the mean lengths of flows parallel to the plate divided by L; C is the plate area fraction responsible for flow-induced heat transfer; D is the effective length of heat transfer contact with the plate divided by L; when without side walls; otherwise .

Table 4 lists the parameters for the three plate orientations developed thus far.

Table 4.

Derivation parameters.

11. Self-Obstruction of Vertical and Downward-Facing Plates

Defined in Formula (14), the Prandtl number () is the momentum diffusivity per thermal diffusivity ratio of a fluid. Heat transfer from plates to fluids with small is primarily conduction. Temperature changes in fluids with large cause changes in density which induce fluid flow that transports heat. The and upper-bound Formulas (42) and (46) are asymptotic for large .

Other than as a factor of , does not affect upward-facing heat transfer because the heated fluid flows directly upward, as does conducted heat. When heated fluid must take longer paths around self-obstructing vertical and downward-facing plates, its heat transfer potential is reduced.

scales with ; is a property of three-dimensional fluids. A function of having values between 0 and 1 should scale in the vertical and downward-facing formulas. Both Schulenberg [14] and Churchill and Chu [5] realized their formulas’ dependence on in this way. Expressing the denominator of vertical Formula (2) as the sixth root of an -norm expression named :

The functions , , and are quite similar. Coefficients 0.492, 0.477, and 0.520 are all within 5% of 1/2. This suggests using 1/2 as the coefficient in a unified function . The -norm p parameters and differ by less than 7%; and lies between them:

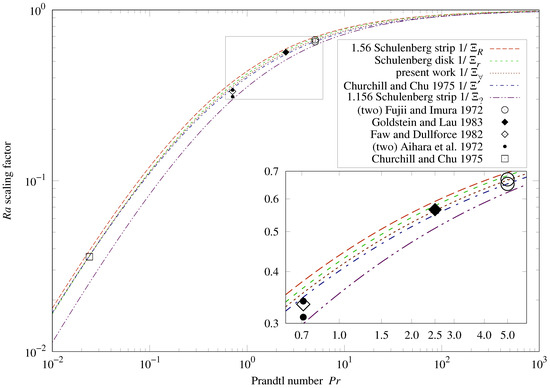

12. Ra Scaling Factors

Figure 4 presents the scaling functions used in the vertical and downward-facing formulas. Also shown are values calculated from coefficients fitted to measurements in the cited sources.

Figure 4.

scaling functions.

Table 5 lists each fitted value and its deviation from each scaling function at the given . Churchill and Chu is closest to the fitted values.

Table 5.

scaling factors.

If a candidate formula is correct, negative deviations of fitted (aggregate) values can result from flow obstructions or measurement bias; positive deviations can result only from measurement bias.

The positive deviations, and , would indict two of the five sources in Table 5. The positive deviations, and , are tolerable.

With values between those of and , is the most plausible of these scaling functions.

The “1.156 Schulenberg strip ” curve in Figure 4 is the scaling function from Formula (3). Section 3 argues that this formula from Schulenberg [14] contained a typographical error. Being 40% less than the other curves at corresponds to Formula (3) taking values 10% less than (corrected) Formula (4).

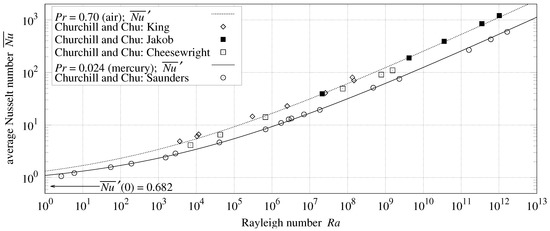

13. Vertical Measurements

Figure 5 and Table 6 present four data-sets from Churchill and Chu [5]. Differences between RMSRE computed from Formula (55) and Churchill and Chu Formula (2) are less than 1%.

Figure 5.

Heat transfer from vertical rectangular plate.

Table 6.

Heat transfer from vertical rectangular plate.

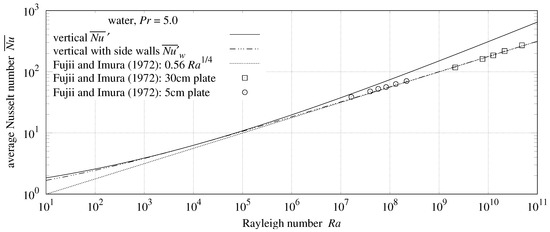

14. Downward-Facing Measurements

Figure 6.

Downward convection heat transfer from horizontal plate.

Table 7.

Downward convection heat transfer from horizontal plate.

15. Characteristic Length Metrics

For upward convection, (area-to-perimeter ratio) is well-defined for any flat, convex plate.

16. Downward-Facing Circular Plate

Schulenberg Equations (4) and (5) for downward-facing strips and disks have matching exponents, but their coefficients and characteristic lengths differ: is of the rectangle’s shorter side, versus disk radius R. Can Formula (56) predict heat transfer for both shapes using a single characteristic length metric?

16.1. Harmonic Mean

Figure 1b shows fluid closest to the heated surface flowing outward from the mid-line. If the plate edge is at varying distances from the mid-line (in the direction of flow), then some sort of length averaging is needed. The flow will be faster over shorter distances because it experiences less drag; this suggests the use of the “harmonic mean”, in which small values have more influence than large.

For rectangles and disks, the mid-line is one of the plate’s equal-area bisectors. For rectangles it is parallel to the longer sides; but it is not the longest bisector, which is diagonal. Being parallel to the longer sides implies that the mid-line is perpendicular to the shorter sides. It will also be perpendicular to the shortest equal-area bisector; and this works for disks as well, where all diameters are bisectors.

Consider a flat heated surface with its convex perimeter defined by functions and within the range along the equal-area bisector which is perpendicular to the shortest equal-area bisector. Let be the combined harmonic mean of and :

For rectangular plates, Formula (57) is of the shorter side’s length, the same characteristic length used by Schulenberg [14]. For disks of radius R:

16.2. Recalculate Conduction

The derivation of downward Formulas (46) and (56) was for a square plate. To derive the downward formula for a disk, will be recalculated; it will be scaled larger because of the increased flow over shorter distances. Recalling from Section 7, the conduction shape factor for one side of a disk is .

Upward-facing disk was scaled by in Formula (27) because its flow was midway between parallel and radially inward; downward-facing was unscaled in (rectangle) Formula (44). The flow from a downward-facing disk spreads from a diameter; an intermediate scale is needed. The geometric mean of 1 (unscaled) and is . Scaling by the reciprocal, , yields the rectangular . With the harmonic mean metric (57) and , the rest of the derivation is unchanged. Thus, the downward Formula (56) works for both rectangular and circular plates.

16.3. Measurements

16.4. Rectangle Shape Factor

derives an exact expression for the rectangular plate’s dimensionless shape factor :

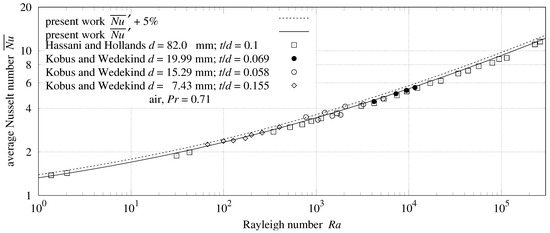

17. Vertical Circular Plate

Consider a flat vertical plate as an array of narrow vertical plates. With , integrate h across the vertical slices of heights ; then solve for in :

Therefore, the vertical characteristic length is the harmonic mean of vertical spans .

For a rectangle of height L, . For the disk of radius R, . Recalculating :

Instead of the bifurcated flow from the downward-facing plate, flow is along full vertical spans of the disk; 1/2 of the diameter-to-circle fringing which scaled downward-facing disk by should apply to vertical disks. With this scaling, , and the rest of the derivation is unchanged. Thus, the vertical Formula (55) works for disks and axis-aligned rectangular plates using harmonic mean Formula (61).

Measurements

Kobus and Wedekind [9] measured natural convection heat transfer from vertical thermistor disks in air. They also included a series of similar measurements from Hassani and Hollands (1987). was not specified; 0.71 is assumed. Each disk’s diameter d and thickness t are specified in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Heat transfer from vertical disk.

Air heated by the two disk sides flows over the upper half of the rim, inhibiting upper-rim heat transfer. The lower half of the rim transfers heat at the same per-area rate as the sides. The disk effective surface area, including half of the rim, is . Being normalized for the area, should be scaled by:

To convert characteristic lengths to the harmonic mean, Kobus and Wedekind gets scaled by ; gets scaled by and Formula (63). Hassani and Hollands used different characteristic lengths for and ; their gets scaled by , while gets scaled by and Formula (63).

Table 8.

Heat transfer from vertical disk.

In the clever design using thermistors, only horizontal clearance and the wires attached to the disk centers remained as obstructions, achieving a close match with the present theory in Table 8.

18. Upward-Facing Square Plate

Converting square plate Formula (33) from to is divided by 4. Expanding from Equation (60):

The square plate’s flow will be moderately radial, scaling midway between the reciprocal of from the upward-facing disk, and from the downward-facing disk’s bifurcated flow. The geometric mean of and is . Scaling by yields from Equation (21). The rest of the derivation is unchanged. Thus, the upward convection Formula (30) works for disks and square plates.

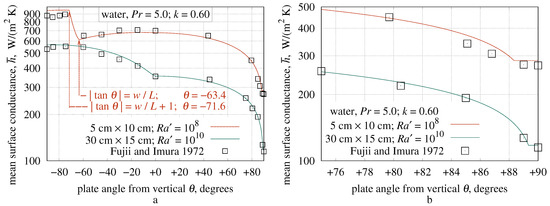

19. Vertical Rectangular Plate With Side Walls

The Fujii and Imura [1] apparatus had (unheated) perpendicular side walls of length forming a channel with the plate. In Table 9, the vertical 30 cm and 5 cm plates average 44% and 18% less heat transfer than expected by vertical Formula (55). Clearly, Formula (55) is incorrect for vertical plates with side walls.

Table 9.

Vertical Fujii and Imura plates.

Formula (65) incorporates an additional factor of in to model the side-wall drag. The side walls obstruct horizontal flow, so the combined length of flow along the plate and side wall is ; heat transfer contact along the plate is L. The -norm changes to the -norm (addition):

Using the general Formula (48) with , , and :

Table 9 details the performance of Formula (67) for vertical plates with side walls. RMSRE of 2.2% and 5.2% are substantial decreases from 43.8% and 18.9%. Figure 8 shows , as required by efficiency constraints.

Figure 8.

Vertical Fujii and Imura plates.

20. Upward-Facing Rectangular Plate With Side Walls

The area-to-perimeter ratio for side-walled upward-facing plates exclude side-wall length from the perimeter length () because there is no flow through side walls. Thus, .

In Table 3 (and Table 10), the Fujii and Imura data-sets averaged 0.4% and 11.4% less than expected from Formula (30). The 30 cm plate having side walls twice as long as its 15 cm channel width made its flow similar to vertical plate flow in each half of the plate towards the center line. .

Table 10.

Upward-Facing Fujii and Imura plates.

Fluid rises after heating; so the and heat transfer factors are both . As with the side-walled vertical plate, conduction and flow-induced heat transfer combine using the -norm (addition):

Flow is partially obstructed by the side walls; hence, will be scaled by . Using the general Formula (48) with , , , , and :

Figure 9 and Table 10 show that Formula (70) is effective for the 30 cm plate, but not for the 5 cm plate. The 5 cm plate’s 10 cm channel width is twice the 5 cm side-wall length. This makes its flow more radial than parallel. Thus, Formula (30) is more appropriate for the 5 cm plate.

Figure 9.

Upward-Facing Fujii and Imura plates.

Table 11 lists the general derivation Formula (48) parameters for the side-wall flow topologies.

Table 11.

Side-walled plate parameters.

21. Inclined Plate

Let be the angle of a plate from vertical. Face up ; vertical ; face down . This investigation has derived and tested formulas for rectangular and circular plates at , , and .

Following Fujii and Imura [1], the argument to vertical Formula (55) gets scaled by to model the reduced vertical convection from an inclined plate. (Fujii and Imura [1] credits B. R. Rich with the idea of scaling vertical by . It can be thought of as a reduction in the effective gravitational acceleration g, which scales linearly.) Following Raithby and Hollands [17], the and arguments to the upward and downward Formulas (30) and (56) get scaled by .

Raithby and Hollands take the maximum convective surface conductance , not , to determine the overall convection. This is because , , and have different characteristic lengths, while is independent of L. Taking the maximum asserts that the associated flow topologies are mutually exclusive. This extreme competition is the -norm, which is equivalent to the function when all its arguments are non-negative:

Rayleigh numbers can be expressed in terms of (vertical plate) :

The downward-facing topology flows outward from opposite plate edges; there is no plate area available for the vertical flow topology. Thus, and are mutually exclusive in Formula (72). The upward-facing topology draws fluid from the whole perimeter. Thus, and are mutually exclusive in Formula (73). Note that Formula (73) mutual exclusion may not hold when part of the perimeter flow is obstructed.

Ideally, when , should be independent of . For a 1 m square plate in fluid, , but . When forces to 0, only the conduction term remains. As noted in Section 7.5, Formula (30) does not extend to static conduction.

and track measurements well near in Figure 3, Figure 5, and Figure 7. Ignoring when , and when , avoids the conduction term competition at :

Note that and are true for any flat, convex plate face.

With , the proposed Formula (74) will match non-side-walled horizontal and vertical plate measurements to their appropriate , , and values.

22. Inclined Plate With Side Walls

The Fujii and Imura [1] apparatus had length side walls. In Table 7, the Formula (56) has less than 5% RMSRE; it is used as the side-walled downward-facing formula with , regardless of which side is shorter.

To adapt Formulas (72) and (73) to apparatus with side walls, Formula (67) replaces . This leads to proposed downward Formula (75) for side-walled plates:

Fujii and Imura photographs show the plume originating in the middle of the 5 cm plate when . The origin shifts 9% toward the elevated end of the plate when . The plume for the 30 cm plate at originates in the upper 1/4 of the plate. Plume movement with indicates that regions of upward-facing and vertical convection shared the side-walled plate in the Fujii and Imura apparatus.

The side-walled upward and vertical topologies compete for horizontal flow in the channel. If competition were between perpendicular flows, they would combine as the root-sum-squared, which is the -norm. To compete for horizontal channel flow, two changes in direction are required; they combine as the -norm.

The 30 cm plate has side walls twice as long as its channel width w. Flow through this channel will be primarily parallel, as modeled by Formula (70). The proposed upward formula for the 30 cm plate is:

The 5 cm plate’s 10 cm channel is twice as wide as its length; the horizontal flow will be more radial than parallel. At it is modeled by Formula (30), but with characteristic length .

Fujii and Imura streamline photographs show the vertical and upward-facing flow modes having uniform rates of the horizontal flow between the lower heated plate edge and pause elevation .

Uniform horizontal flow is not the case for the 5 cm plate at . The horizontal flow is slower near the lower plate edge and increases with elevation. The plume lacks a clear origin. It does not match any flow topology described thus far.

The upward-facing flow topology has bilateral symmetry; there is no flow between the halves created by severing along a plane of symmetry. Thus, half of the upward-facing flow topology is also a flow topology. Its general Formula (48) parameters are the same as the upward-facing topology, except that . The flow topology is modeled as the -norm of and , where is the heat transfer from this half upward flow topology. The proposed upward formula for the 5 cm plate is:

At , heat transfer is ; so . At , it is ; so . The transition between and depends on , w, and . Dimensional analysis yielding Formula (78) localizes the transition to , whose bounds are marked by arrows in Figure 10a.

Figure 10.

(a) Inclined Fujii and Imura plates; (b) Inclined plate detail.

Table 7, Table 9, Table 10, and Table 12 show that the present theory is sufficient to explain, with RMSRE between 2.2% and 6.0%, the Fujii and Imura heat transfer measurements of horizontal, vertical, and inclined plates.

Table 12.

Inclined plate heat transfer.

23. Results

Table 13 summarizes statistics for the eighteen data-sets presented in Figure 3, Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9 and Figure 10, and their associated tables. They are grouped by orientation and ordered by decreasing error relative to the present work, All but three of these data-sets have RMSRE of 6% or less, quantitatively supporting the present theory for horizontal, vertical, and inclined plates.

Table 13.

Measurements versus present theory.

24. Discussion

Rennó and Ingersoll [12] and Goody [13] found that the heat-engine efficiency limit for atmospheric convection is 1/2 of the reversible heat-engine efficiency limit . This investigation finds that is the limit for external natural convection generally. Reversible heat engines, such as Stirling engines, can be more efficient than . External convection is not reversible.

The Fujii and Imura [1] side-walled plates do not qualify as external because fluid was not free to flow horizontally near the plate. The side wall formulas are not general, particularly for square plates. They were investigated primarily to gauge how well the combination of -norm with trigonometric scaling of explains heat transfer from inclined plates.

Evidence from Lloyd and Moran [4], and statements in Fujii and Imura [1] and Churchill and Chu [5], that the laminar-turbulent transition was irrelevant to natural convection heat transfer were published in the early 1970s. Yet, the belief that it governs external plate natural convection heat transfer has persisted [2,11,17].

Much of the subsequent natural convection literature investigates local flow properties. Such studies do not inform this investigation’s systemic-invariant analysis. However, streamline photographs were crucial to characterizing the flow topologies and deriving the present formulas.

The pause in horizontal flow above the upward-facing 5 cm plate is visible in the photograph from Fujii and Imura [1]. Their photographs of vertical and downward-facing plate streamlines do not include enough of the fluid above the plates to see the horizontal pause expected by this investigation.

The harmonic mean integral in Formulas (57) and (61) converges only when the perimeter curve is perpendicular to the integration axis at both integration limits. For downward-facing plates this includes all circles, ellipses, and rectangles; for vertical plates, this includes all circles and ellipses, and trapezoids (including rectangles) with two vertical edges. When , vertical plate scales with . Hence, the heat flow rate is sensitive to only at small values.

25. Conclusions

Using a novel methodology based on streamline photographs, dimensional analysis, and the thermodynamic constraints on heat-engine efficiency, this investigation:

- Derived from first principles a previously unknown comprehensive heat transfer formula for upward-facing convection;

- Extended the scope of vertical and downward-facing formulas from rectangles to other shapes with convex perimeters using the harmonic mean for the characteristic length metric;

- Unified the dependence of vertical and downward-facing plates.

A comprehensive and exact model for natural convection from an external, isothermal flat surface can now be succinctly stated. For horizontal upward-facing plates:

For vertical and downward-facing plates, the convection reduction due to self-obstruction is the scaling factor , yielding comprehensive formulas for vertical and downward :

The reduction in effective gravitational acceleration g also scales . The average convective surface conductance for an external, isothermal plate inclined at angle from vertical is:

- The upward-facing characteristic length is the area-to-perimeter ratio.

- The vertical characteristic length is the harmonic mean of the perimeter vertical spans.

- The downward-facing characteristic length is the harmonic mean of the perimeter distances to that bisector which is perpendicular to the shortest bisector.

- is the Rayleigh number computed with vertical characteristic length .

- ; and .

The harmonic mean metrics extend vertical and downward-facing to non-rectangular plates.

The present theory was compared with eighteen data-sets from seven peer-reviewed articles, testing circular, rectangular, and inclined rectangular plates, laminar and turbulent flows, with and . All except three of the data-sets had between 2% and 6% RMSRE from the present theory.

- The formula improves accuracy and range substantially over the piece-wise power laws currently employed for predicting upward convection heat transfer.

- With less than 1% difference between and the Churchill and Chu (1975) vertical formula, there is little need to replace it in existing applications.

- However, the published Schulenberg (1985) formula can return values which are 10% smaller than ; should replace it.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/thermo3010010/s1: a zip archive of the measurements extracted from prior works which were compared with the present theory.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Dave Custer, Rich Hilliard, Roberta Jaffer, and anonymous reviewers for their useful suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declare no conflict of interest.

Nomenclature

| Latin Letters | |

| average Nusselt number | |

| average surface conductance () | |

| Prandtl number | |

| Rayleigh number | |

| Reynolds number | |

| A | plate area () |

| B | sum of mean lengths of plate parallel flows divided by L |

| C | plate area fraction responsible for flow induced heat transfer |

| fluid specific heat at constant pressure () | |

| D | effective length of heat transfer contact with plate divided by L |

| E | count of changes in direction of fluid flow |

| g | gravitational acceleration () |

| I | power flux () |

| k | fluid thermal conductivity () |

| L | characteristic length (m) |

| M | air molar mass () |

| P | air pressure () |

| q | conduction power (W) |

| R | disk radius (m) |

| S | conduction shape factor (m) |

| Schmidt number | |

| T | temperature (K) |

| u | fluid velocity () |

| V | air volume () |

| W | work (J) |

| w | distance between side walls |

| perimeter functions (m) | |

| Greek Letters | |

| fluid thermal diffusivity () | |

| fluid thermal expansion coefficient () | |

| heat energy (J) | |

| temperature difference (K) | |

| thermodynamic heat-engine efficiency | |

| fluid kinematic viscosity () | |

| dimensionless variable groups | |

| fluid density () | |

| surface angle from vertical ( is face up) | |

| self-obstruction (reciprocal) factor | |

| Superscripts | |

| vertical plate | |

| * | upward-facing plate |

| Subscripts | |

| 0 | conduction |

| ∀ | unified |

| ∞ | bulk fluid |

| × | misprinted formula |

| A | atmospheric natural convective |

| i | induced flow along plate |

| k | kinetic |

| N | natural convective |

| p | plate |

| R | downward-facing plate |

| r | downward-facing disk |

| S | dimensionless shape factor |

| t | ideal turbine |

| w | with side walls |

Abbreviation

The following abbreviation is used in this manuscript:

| RMSRE | root-mean-squared relative error |

References

- Fujii, T.; Imura, H. Natural-convection heat transfer from a plate with arbitrary inclination. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 1972, 15, 755–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitamura, K.; Mitsuishi, A.; Suzuki, T.; Kimura, F. Fluid flow and heat transfer of natural convection adjacent to upward-facing, rectangular plates of arbitrary aspect ratios. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2015, 89, 320–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aihara, T.; Yamada, Y.; Endö, S. Free convection along the downward-facing surface of a heated horizontal plate. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 1972, 15, 2535–2549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, J.; Moran, W. Natural convection adjacent to horizontal surface of various planforms. J. Heat Transf. 1974, 96, 443–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churchill, S.W.; Chu, H.H. Correlating equations for laminar and turbulent free convection from a vertical plate. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 1975, 18, 1323–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churchill, S.W.; Usagi, R. A general expression for the correlation of rates of transfer and other phenomena. AIChE J. 1972, 18, 1121–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lienhard, J.H., IV; Lienhard, J.H., V. A Heat Transfer Textbook, 5th ed.; Version 5.10; Phlogiston Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein, R.; Sparrow, E.; Jones, D. Natural convection mass transfer adjacent to horizontal plates. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 1973, 16, 1025–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobus, C.; Wedekind, G. An experimental investigation into forced, natural and combined forced and natural convective heat transfer from stationary isothermal circular disks. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 1995, 38, 3329–3339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faw, R.; Dullforce, T. Holographic interferometry measurement of convective heat transport beneath a heated horizontal circular plate in air. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 1982, 25, 1157–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, R.J.; Lau, K.S. Laminar natural convection from a horizontal plate and the influence of plate-edge extensions. J. Fluid Mech. 1983, 129, 55–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rennó, N.; Ingersoll, A. Natural convection as a heat engine: A theory for CAPE. J. Atmos. Sci. 1995, 53, 572–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goody, R. On the Mechanical Efficiency of Deep, Tropical Convection. J. Atmos. Sci. 2003, 60, 2827–2832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulenberg, T. Natural convection heat transfer below downward facing horizontal surfaces. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 1985, 28, 467–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fermi, E. Thermodynamics; Dover Books in Physics and Mathematical Physics; Dover Publications: Mineola, NY, USA, 1956. [Google Scholar]

- Incropera, F.; DeWitt, D.; Bergman, T.; Lavine, A. Fundamentals of Heat and Mass Transfer; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Rohsenow, W.; Hartnett, J.; Cho, Y. Handbook of Heat Transfer; McGraw-Hill Handbooks; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).