Surface Engineering of PET Fabrics with TiO2 Nanoparticles for Enhanced Antibacterial and Thermal Properties in Medical Textiles

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. In Situ Immobilization of TiO2 Nanoparticles (NPs) on PET Fabric

2.3. Characterization of Surface and Chemical Properties

2.4. Antibacterial Evaluation

2.5. Characterization of Thermophysiological Comfort and Thermal Properties

2.5.1. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

2.5.2. Thermal Conductivity

2.5.3. Thermal Resistance

2.5.4. Relative Water Vapor Permeability

2.5.5. Air Permeability

2.5.6. Infrared Thermography

3. Results and Discussion

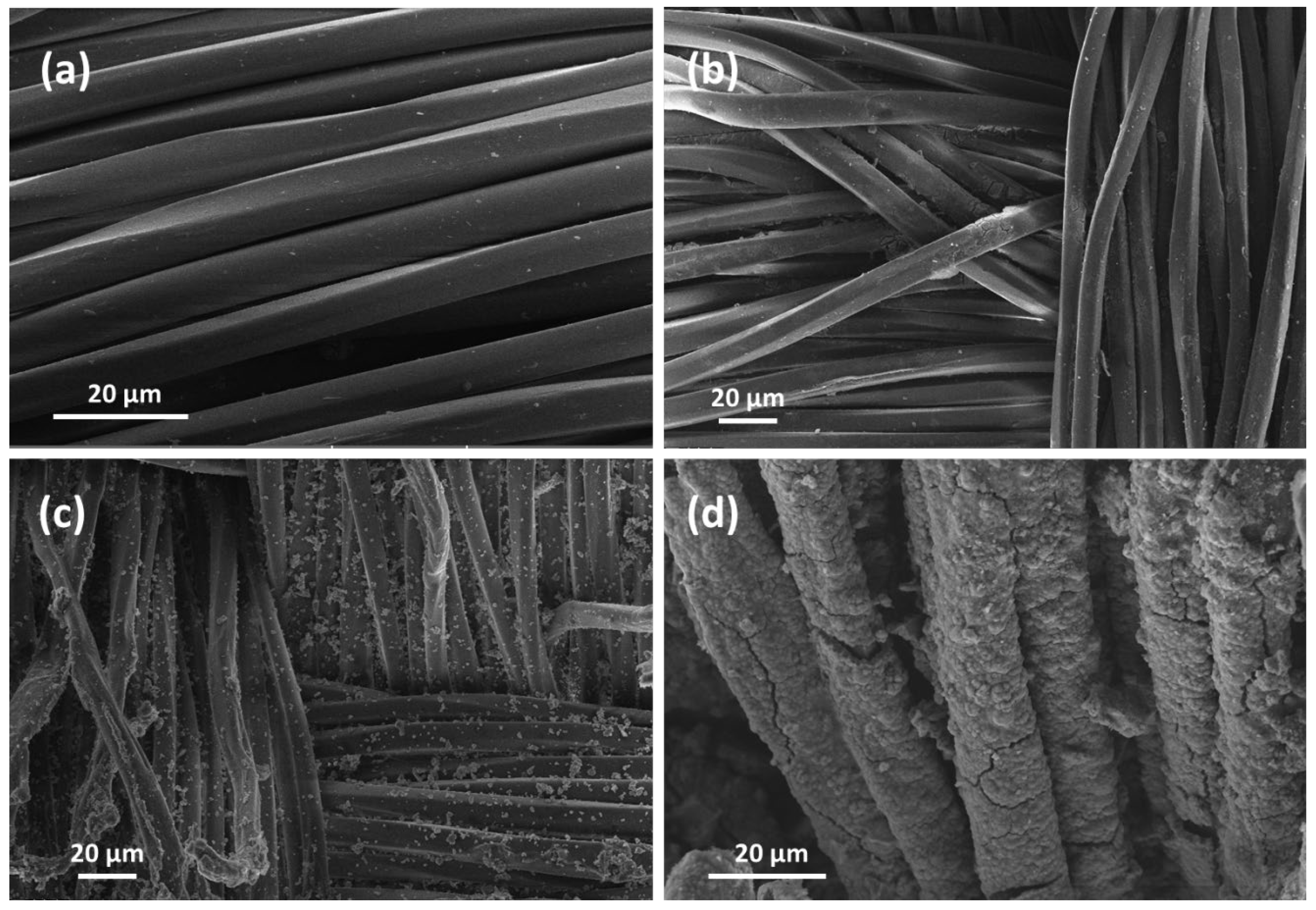

3.1. SEM Analysis of TiO2 NPs-Coated PET Samples

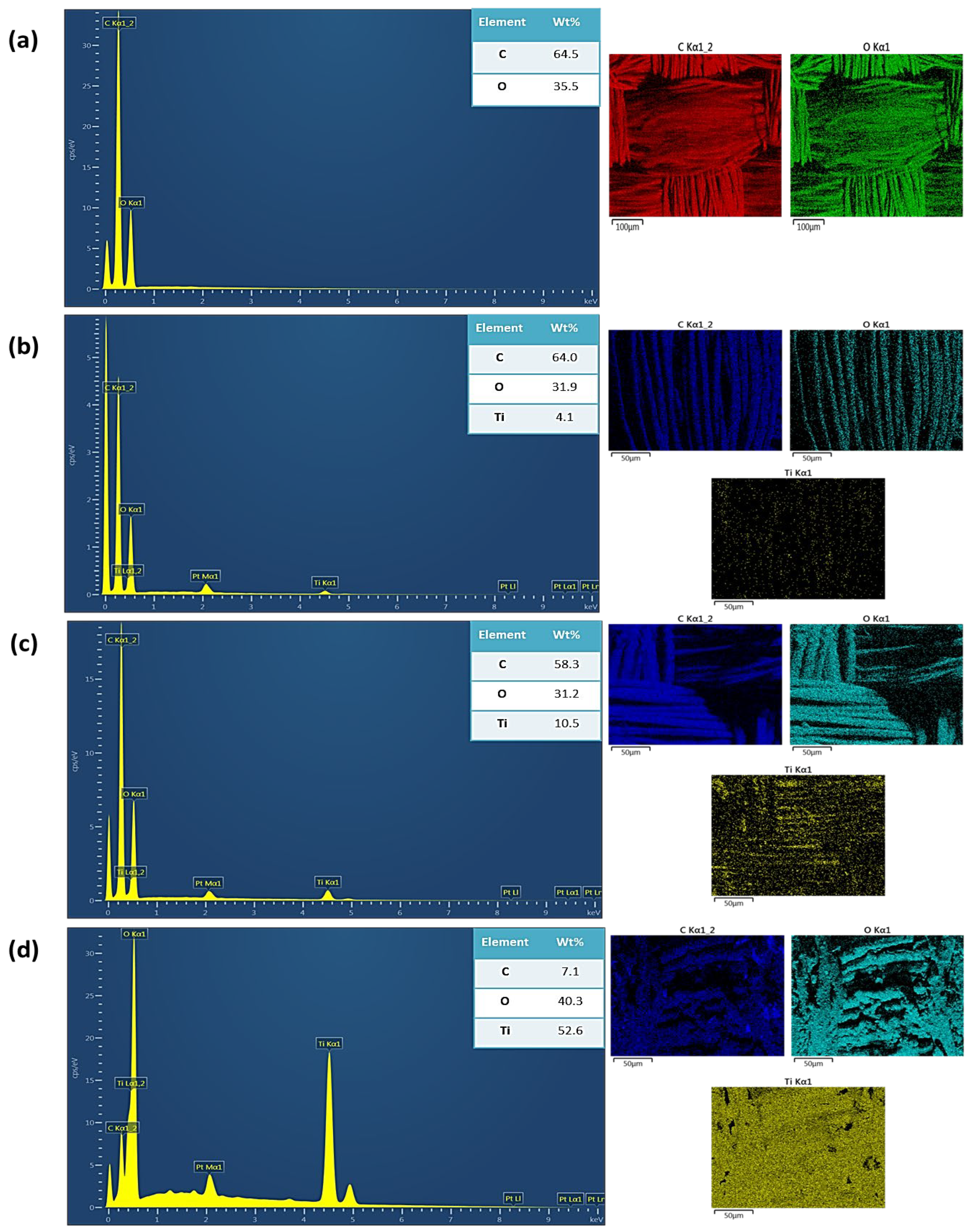

3.2. EDS Analysis of TiO2 NPs-Coated PET Samples

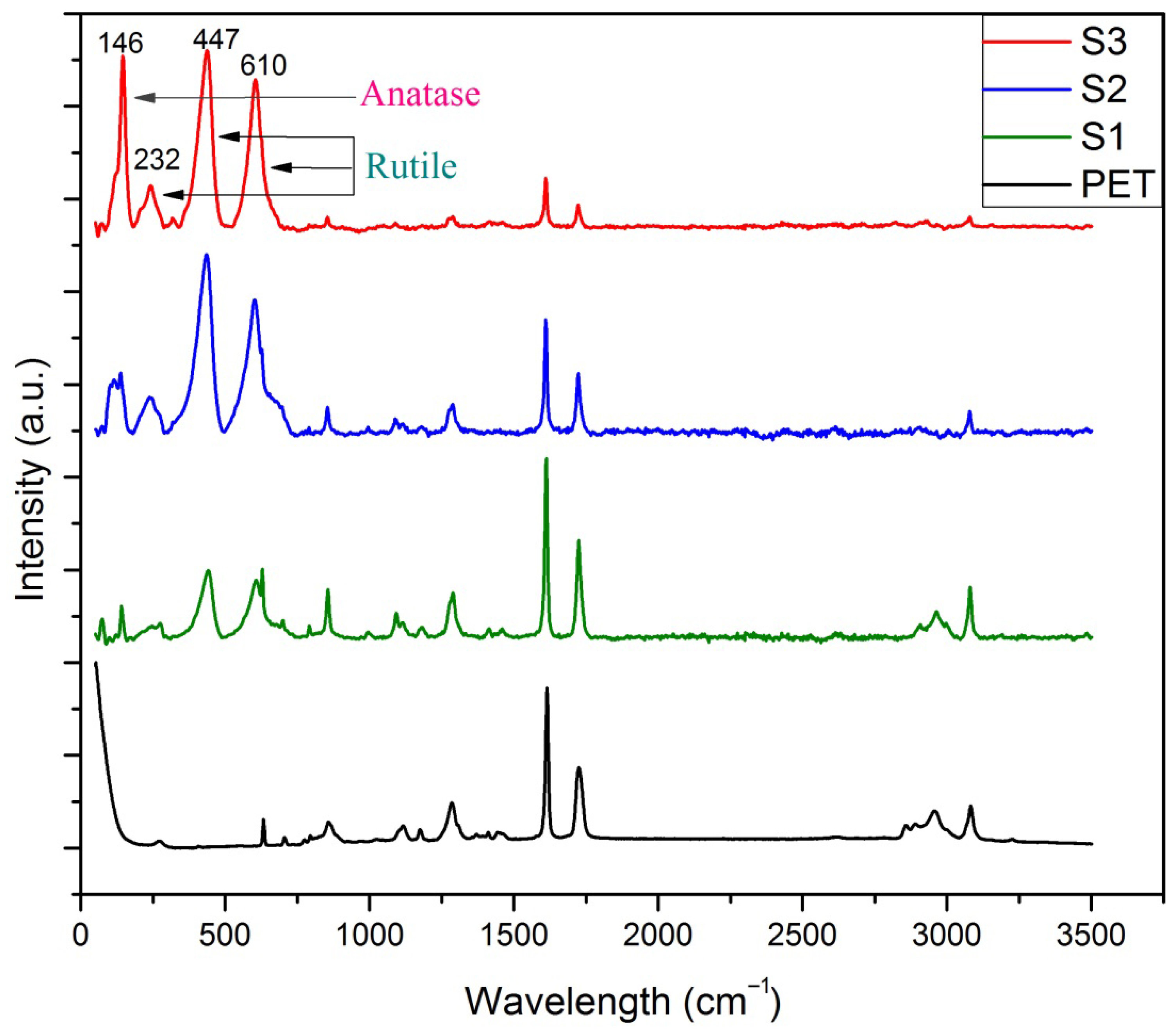

3.3. Raman Spectroscopy of TiO2 NPs-Coated PET Fabrics

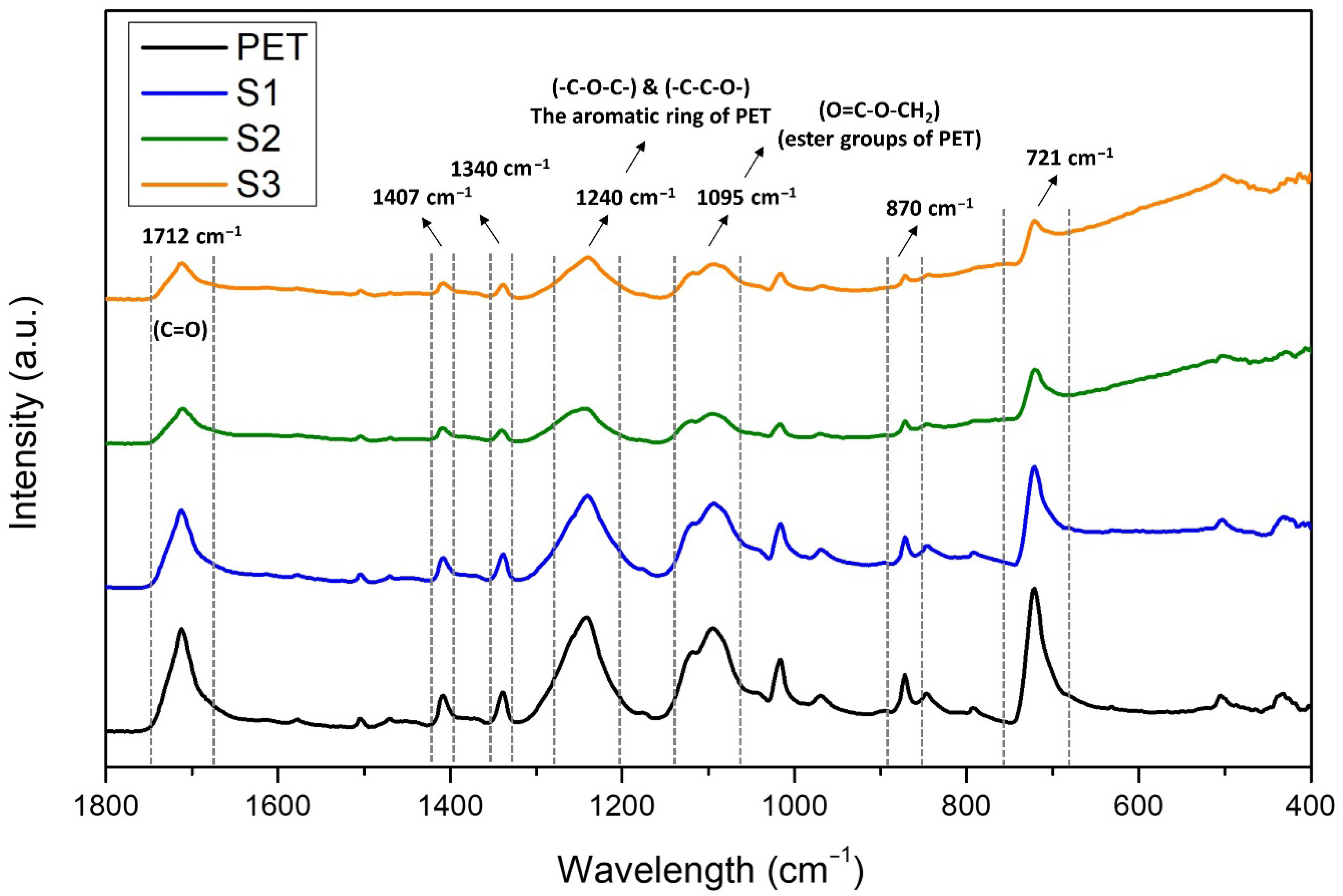

3.4. FT-IR Analysis

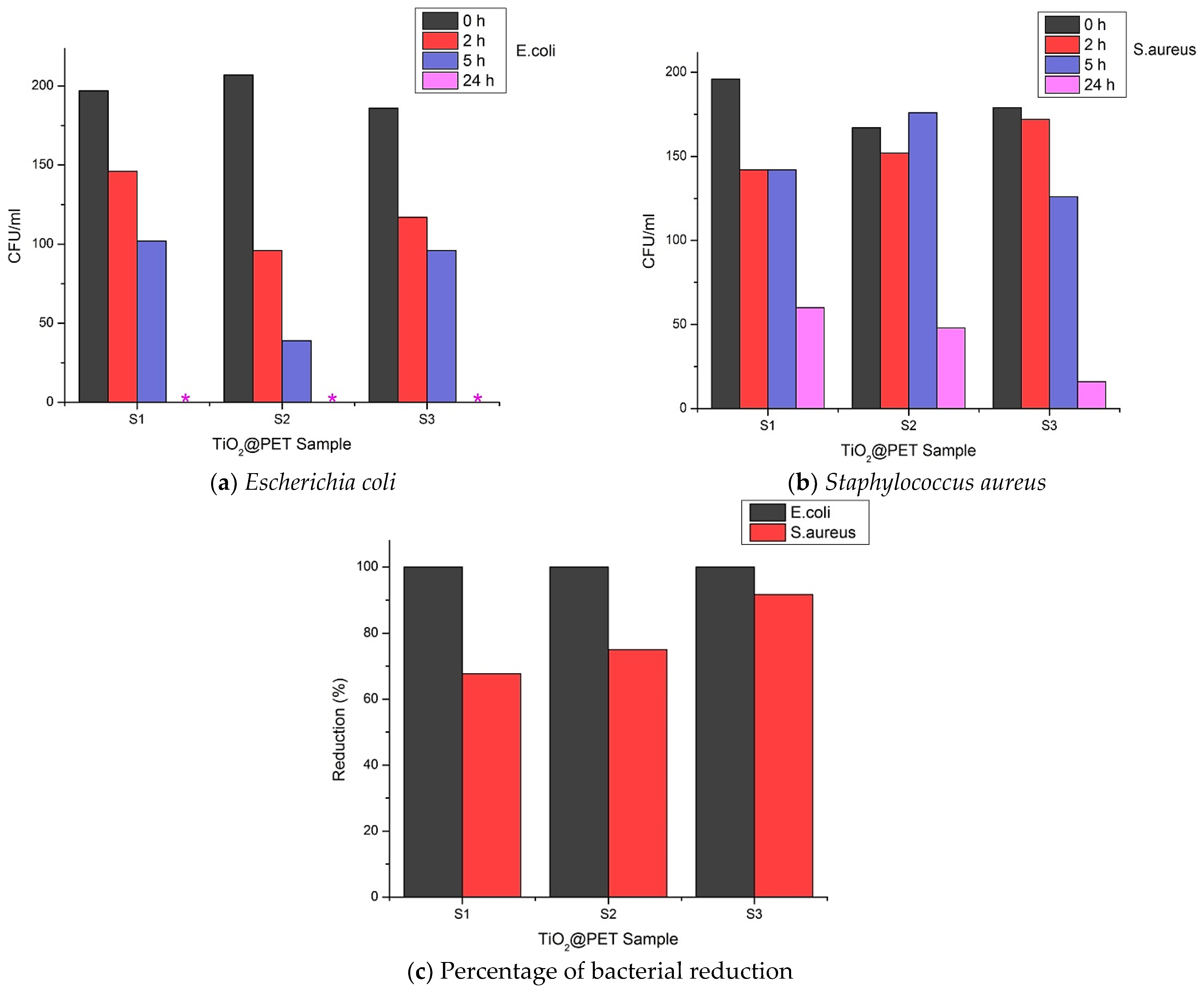

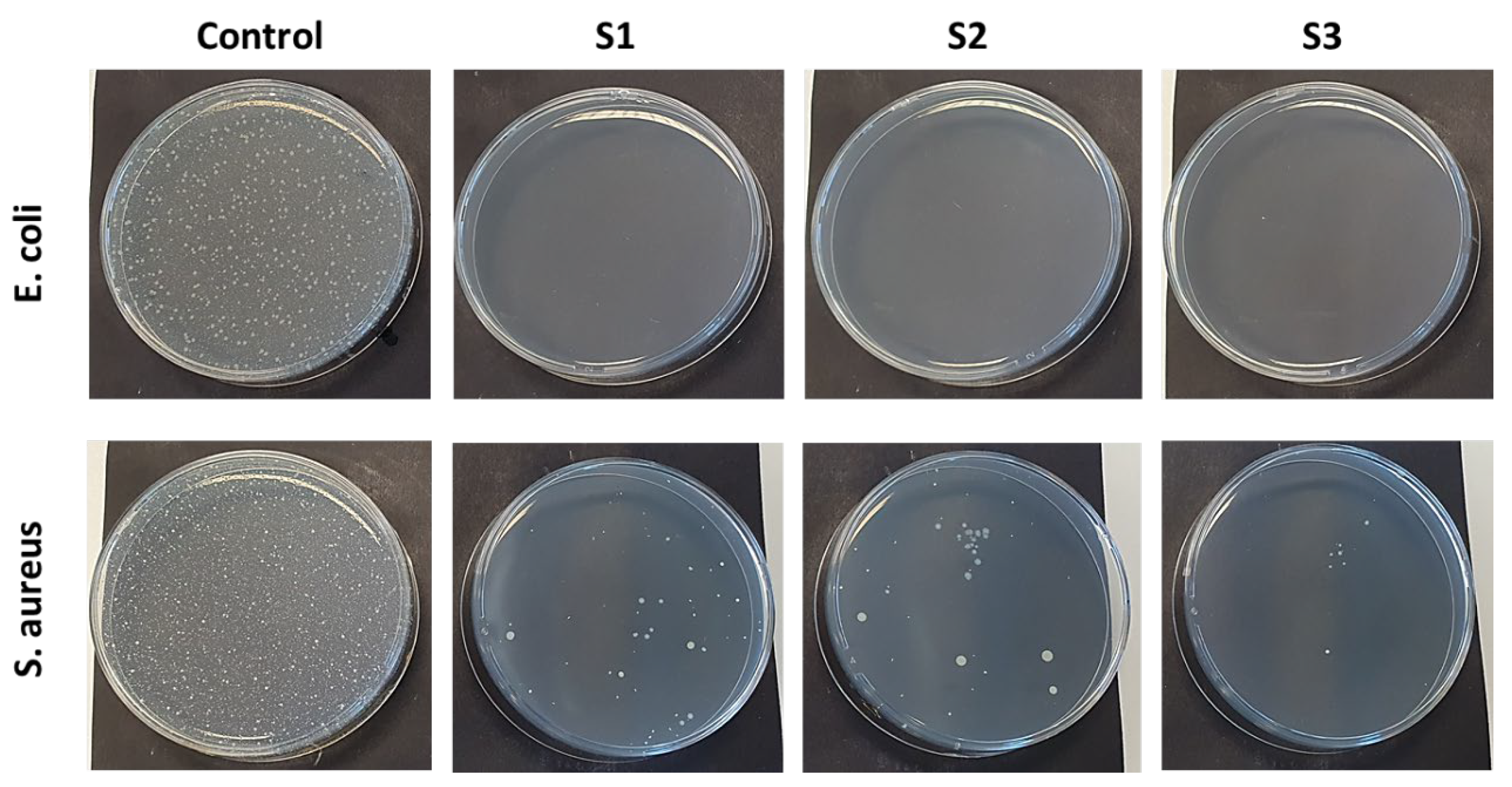

3.5. Antibacterial Performance

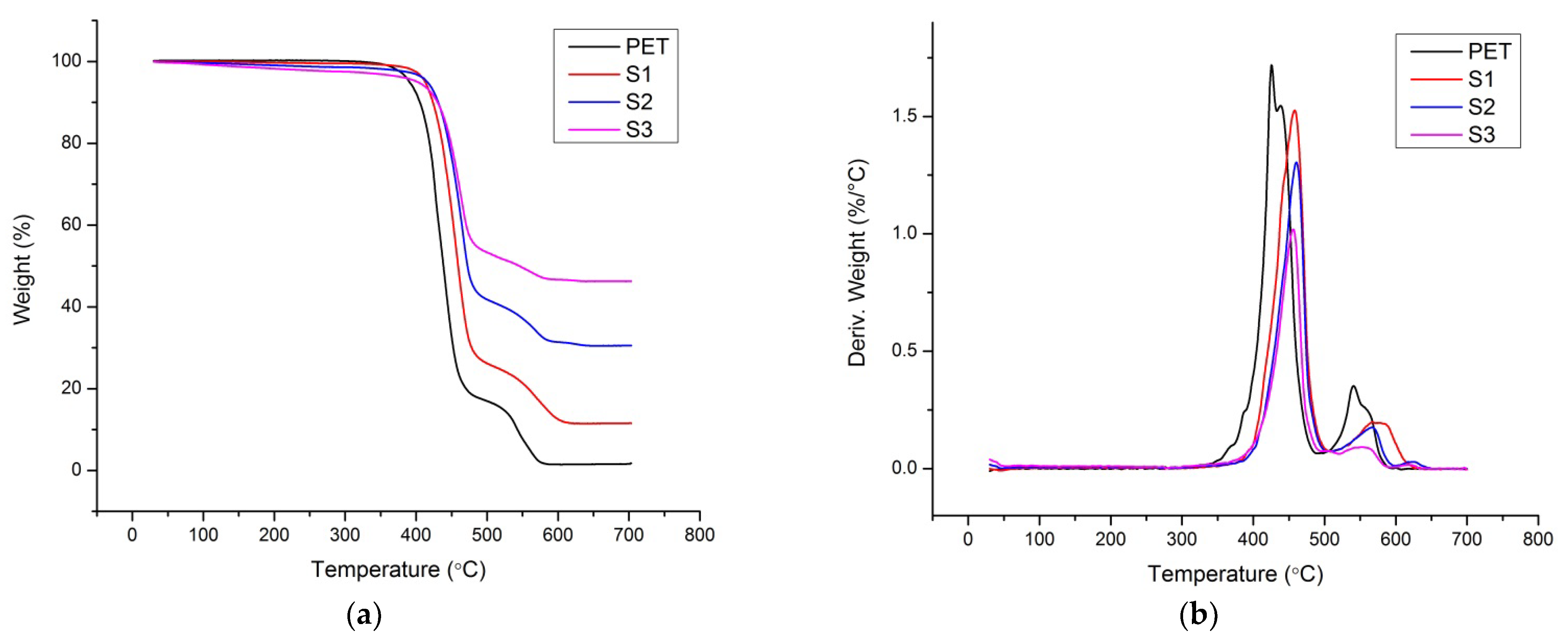

3.6. Thermal Stability

3.7. Thermal Insulation Index (I)

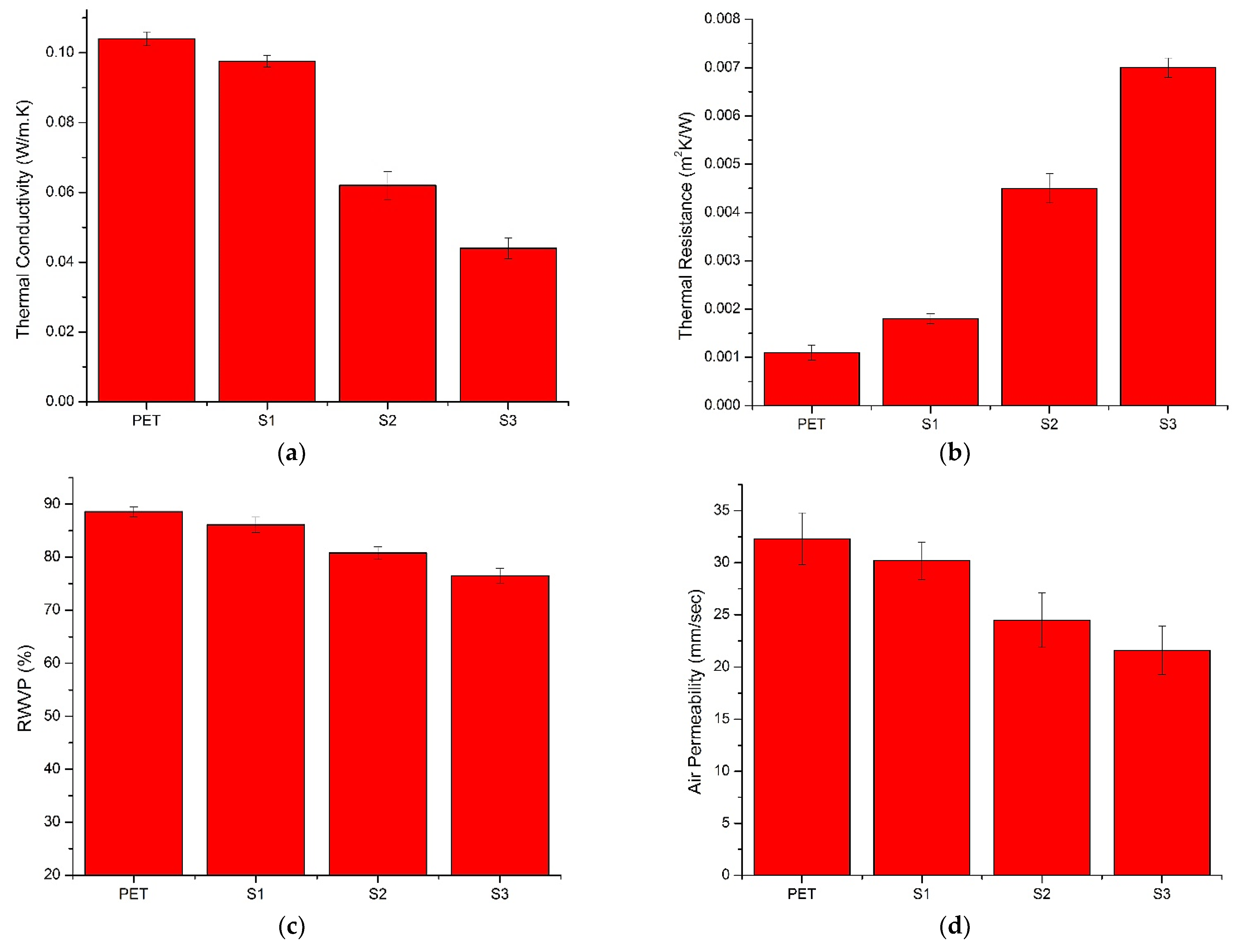

3.8. Thermal Conductivity

3.9. Thermal Resistance

3.10. Relative Water Vapor Permeability (RWVP)

3.11. Air Permeability (AP)

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rivero, P.J.; Urrutia, A.; Goicoechea, J.; Arregui, F.J. Nanomaterials for functional textiles and fibers. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2015, 10, 501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chokesawatanakit, N.; Thammasang, S.; Phanthanawiboon, S. Enhancing the multifunctional properties of cellulose fabrics through in situ hydrothermal deposition of TiO2 nanoparticles at low temperature for antibacterial self-cleaning under UV–Vis illumination. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 256, 128321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thi, Q.; Huong, T.; Thanh, N.; Nam, H.; Hai, N.D.; Dat, N.M. Surface modification and antibacterial activity enhancement of acrylic fabric by coating silver/graphene oxide nanocomposite. J. Polym. Res. 2023, 30, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kübra, A.; Çevik, S. Electrospray deposited plant-based polymer nanocomposite coatings with enhanced antibacterial activity for Ti-6Al-4V implants. Prog. Org. Coat. 2024, 186, 107965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Cao, Y.; Zhen, Q.; Hu, J.-J.; Cui, J.-Q.; Qian, X.-M. Facile Preparation of PET/PA6 Bicomponent Microfilament Fabrics with Tunable Porosity for Comfortable Medical Protective Clothing. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2022, 5, 3509–3518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassabo, A.G.; Elmorsy, H.M.; Gamal, N.; Sedik, A.; Saad, F.; Bouthaina, M.; Othman, H.A. Applications of nanotechnology in the creation of smart sportswear for enhanced sports performance: Efficiency and comfort. J. Text. Color. Polym. Sci. 2023, 20, 11–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, J.; Zhao, Y.; Meng, Y.; Su, J.; Han, J. Long-lasting superhydrophobic antibacterial PET fabrics via graphene oxide promoted in-situ growth of copper nanoparticles. Synth. Met. 2023, 293, 117293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oopath, S.V.; Baji, A.; Abtahi, M.; Luu, T.Q.; Vasilev, K.; Truong, V.K. Nature-inspired biomimetic surfaces for controlling bacterial attachment and biofilm development. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 10, 2201425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, M.; Liu, S.; Deflorio, W.; Hao, L.; Wang, X.; Salazar, K.S.; Taylor, M.; Castillo, A.; Cisneros-zevallos, L.; Oh, J.K.; et al. Influence of surface roughness, nanostructure, and wetting on bacterial adhesion. Langmuir 2023, 39, 5426–5439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özen, İ.; Çinçik, E.; Şimşek, S. Thermal comfort properties of simulated multilayered diaper structures in dry and wet conditions. J. Ind. Text. 2016, 46, 256–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.Z.; Hussain, S.; Siddique, H.F.; Baheti, V.; Militky, J.; Azeem, M.; Ali, A. Improvement of liquid moisture management in plaited knitted fabrics. Tekst. Konfeksiyon 2018, 28, 182–188. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.Z.; Baheti, V.; Ashraf, M.; Hussain, T.; Ali, A.; Javid, A.; Rehman, A. Development of UV protective, superhydrophobic and antibacterial textiles using ZnO and TiO2 nanoparticles. Fibers Polym. 2018, 19, 1647–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuenyongsuwan, J.; Nithiyakorn, N.; Sabkird, P.; O’Rear, E.A.; Pongprayoon, T. Surfactant effect on phase-controlled synthesis and photocatalyst property of TiO2 nanoparticles. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2018, 214, 330–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhao, J.; Sun, L.; Wang, X. A review on the application of photocatalytic materials on textiles. Text. Res. J. 2015, 85, 1104–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujishima, A.; Honda, K. Electrochemical photolysis of water at a semiconductor electrode. Nature 1972, 238, 37–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mutsak Ahmed, R.; Hasan, I. A review on properties and applications of TiO2 and associated nanocomposite materials. Mater. Today Proc. 2023, 81, 1073–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Paola, A.; Bellardita, M.; Palmisano, L. Brookite, the least known TiO2 photocatalyst. Catalysts 2013, 3, 36–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Pillai, S.C.; Falaras, P.; O’Shea, K.E.; Byrne, J.A.; Dionysiou, D.D. New insights into the mechanism of visible light hotocatalysis. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2014, 5, 2543–2554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, J.; Jia, Z. Morphological control and photodegradation behavior of rutile TiO2 prepared by a low-temperature process. Mater. Lett. 2006, 60, 1753–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taziwa, R.; Okoh, O.; Nyamukamba, P.; Zinya, S.; Mungondori, H. Synthetic methods for titanium dioxide nanoparticles: A review. In Titanium Dioxide—Material for a Sustainable Environment; Yang, D., Ed.; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2018; p. 518. ISBN 978-1-78923-327-8. [Google Scholar]

- Ortelli, S.; Costa, A.L.; Dondi, M. TiO2 nanosols applied directly on textiles using different purification treatments. Materials 2015, 8, 7988–7996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.Z.; Baheti, V.; Militky, J.; Wiener, J.; Ali, A. Self-cleaning properties of polyester fabrics coated with flower-like TiO2 particles and trimethoxy (octadecyl)silane. J. Ind. Text. 2019, 50, 543–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.Y.; Li, S.H.; Ge, M.Z.; Wang, L.N.; Xing, T.L.; Chen, G.Q.; Liu, X.F.; Al-Deyab, S.S.; Zhang, K.Q.; Chen, T.; et al. Robust superhydrophobic TiO2 @fabrics for UV shielding, self-cleaning and oil–water separation. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 2825–2832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Deng, H.; Lu, F.; Chen, W.; Su, X. Antibacterial nanocellulose-TiO2/polyester fabric for the recyclable photocatalytic degradation of dyes. Polymers 2023, 15, 4376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salvia Binte Touhid, S.; Shawon, M.R.K.; Ali Khoso, N.; Xu, Q.; Pan, D.; Liu, X. TiO2/Cu composite NPs coated polyester fabric for the enhancement of antibacterial durability. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 774, 12114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghavian, H.; Černík, M.; Dvořák, L. Advanced (bio) fouling resistant surface modification of PTFE hollow-fiber membranes for water treatment. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 11871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghavian, H.; Khan, M.Z.; Wiener, J.; Militky, J.; Tomkova, B.; Venkataraman, M.; Ali, Z.; Cernik, M.; Dvorak, L. Green superhydrophobic surface engineering of PET fabric for advanced water-solvent separation. Prog. Org. Coatings 2024, 197, 108842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.Z.; Taghavian, H.; Wiener, J.; Militky, J. Green in-situ immobilization of ZnO nanoparticles for functionalization of polyester fabrics. Surf. Interfaces 2024, 55, 105336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.Z.; Ashraf, M.; Hussain, T.; Rehman, A.; Malik, M.M.; Raza, Z.A.; Nawab, Y.; Zia, Q. In situ deposition of TiO2 nanoparticles on polyester fabric and study of its functional properties. Fibers Polym. 2015, 16, 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrios, Y.; Perez, L.D.; Soto, C.Y.; Sierra, C. Metal-organic framework (MOFs) tethered to cotton fibers display antimicrobial activity against relevant nosocomial bacteria. Inorganica Chim. Acta 2022, 537, 120955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, S.; Cayer, M.-P.; Ahmmed, K.M.T.; Khadem-Mohtaram, N.; Charette, S.J.; Brouard, D. Characterization of the antibacterial activity of an SiO2 nanoparticular coating to prevent bacterial contamination in blood products. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peer, P.; Sedlaříková, J.; Janalíková, M.; Kučerová, L.; Pleva, P. Novel polyvinyl butyral/monoacylglycerol nanofibrous membrane with antifouling activity. Materials 2020, 13, 3662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hes, L. Non-destructive determination of comfort parameters during marketing of functional garments and clothing. Indian J. Fibre Text. Res. 2008, 33, 239–245. [Google Scholar]

- Mangat, M.M.; Hes, L.; Bajzık, V. Thermal resistance models of selected fabrics in wet state and their experimental verification. Text. Res. J. 2015, 85, 200–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hes, L.; Loghin, C. Heat, moisture and air transfer properties of selected woven fabrics in wet state. J. Fiber Bioeng. Informatics 2009, 2, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogusławska-Baczek, M.; Hes, L. Effective water vapour permeability of wet wool fabric and blended fabrics. Fibres Text. East. Eur. 2013, 97, 67–71. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 11092:2014; Textiles—Physiological Effects—Measurement of Thermal and Water-Vapour Resistance under Steady-State Conditions (Sweating Guarded-Hotplate Test). International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014.

- Hes, L.; de Araujo, M. Simulation of the effect of air gaps between the skin and a wet fabric on resulting cooling flow. Text. Res. J. 2010, 80, 1488–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 9237:1995; Textiles—Determination of the Permeability of Fabrics to Air. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1995.

- Montazer, M.; Sadighi, A. Optimization of the hot alkali treatment of polyester/cotton fabric with sodium hydrosulfite. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2006, 100, 5049–5055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cammarano, A.; De Luca, G.; Amendola, E. Surface modification and adhesion improvement of polyester films. Cent. Eur. J. Chem. 2013, 11, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soundarrajan, P.; Sankarasubramanian, K.; Logu, T.; Sethuraman, K.; Ramamurthi, K. Growth of rutile TiO2 nanorods on TiO2 seed layer prepared using facile low cost chemical methods. Mater. Lett. 2014, 116, 191–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaraju, G.; Manjunath, K.; Ravishankar, T.N.; Ravikumar, B.S.; Nagabhushan, H.; Ebeling, G.; Dupont, J. Ionic liquid-assisted hydrothermal synthesis of TiO2 nanoparticles and its application in photocatalysis. J. Mater. Sci. 2013, 48, 8420–8426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, X.; Gao, X.; Qiu, J.; He, P.; Li, X.; Xiao, X. TiO2 nanorod-derived synthesis of upstanding hexagonal kassite nanosheet arrays: An intermediate route to novel nanoporous TiO2 nanosheet arrays. Cryst. Growth Des. 2012, 12, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramaniam, M.R.; Devanathan, S.; Kumaresan, D. Synthesis of micrometer-sized hierarchical rutile TiO2 flowers and their application in dye sensitized solar cells. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 36791–36799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selman, A.M.; Hassan, Z.; Husham, M. Structural and photoluminescence studies of rutile TiO2 nanorods prepared by chemical bath deposition method on Si substrates at different pH values. Meas. J. Int. Meas. Confed. 2014, 56, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mecozzi, M.; Nisini, L. The differentiation of biodegradable and non-biodegradable polyethylene terephthalate (PET) samples by FTIR spectroscopy: A potential support for the structural differentiation of PET in environmental analysis. Infrared Phys. Technol. 2019, 101, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Lafi, A.G.; Abboudi, M.; Aljoumaa, K. Natural sunlight ageing of control and sterilized poly(ethylene terephthalate): Two-dimensional infrared correlation spectroscopic investigation. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2017, 134, 44736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhullar, S.; Goyal, N.; Gupta, S. FericipXT-coated PEGylated rutile TiO2 nanoparticles in drug delivery: In vitro assessment of imatinib release. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 23886–23901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serov, D.A.; Gritsaeva, A.V.; Yanbaev, F.M.; Simakin, A.V.; Gudkov, S.V. Review of Antimicrobial Properties of Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 10519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krumdieck, S.P.; Boichot, R.; Gorthy, R.; Land, J.G.; Lay, S.; Gardecka, A.J.; Polson, M.I.J.; Wasa, A.; Aitken, J.E.; Heinemann, J.A.; et al. Nanostructured TiO2 anatase-rutile-carbon solid coating with visible light antimicrobial activity. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Liu, C.; Yang, D.; Zhang, H.; Xi, Z. Comparative study of cytotoxicity, oxidative stress and genotoxicity induced by four typical nanomaterials: The role of particle size. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2009, 29, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, M.A.O.; Hassan, S.; Ashraf, Y.; Basuony, Y.; Mostafa, S.T. Enhancing the functional properties of polyester and polyester/cotton fabric via treatment with impregnated metal oxide nanoparticles in the polymer network. Egypt. J. Chem. 2025, 68, 595–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Wu, H.; Wang, M.; Liang, Y. Prediction and optimization of radiative thermal properties of nano TiO2 assembled fibrous insulations. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2018, 117, 729–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood Katun, M.; Kadzutu-Sithole, R.; Moloto, N.; Nyamupangedengu, C.; Gomes, C. Improving thermal stability and hydrophobicity of rutile-TiO2 nanoparticles for oil-impregnated paper application. Energies 2021, 14, 7964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, Z.; Fang, L.; Hong, Z. Immobilization of TiO2 nanoparticles on PET fabric modified with silane coupling agent by low temperature hydrothermal method. Fibers Polym. 2013, 14, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczurek, A.; Tran, T.N.L.; Kubacki, J.; Gąsiorek, A.; Startek, K.; Mazur-Nowacka, A.; Dell’Anna, R.; Armellini, C.; Varas, S.; Carlotto, A.; et al. Polyethylene terephthalate (PET) optical properties deterioration induced by temperature and protective effect of organically modified SiO2–TiO2 coating. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2023, 306, 128016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, C.; Lin, C.; Hong, P. Melt-spinning and thermal stability behavior of TiO2 nanoparticle/polypropylene nanocomposite fibers. J. Polym. Res. 2011, 18, 367–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei Qazviniha, M.; Piri, F. Preparation, identification, and evaluation of the thermal properties of novolac resins modified with TiO2, MgO, and V2O5 oxides. Mech. Adv. Compos. Struct. 2024, 11, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Zhu, J.; Liao, X.; Ni, H. Thermal behavior of poly (ethylene terephthalate)/SiO2/TiO2 nano composites prepared via in situ polymerization. J. Iran. Chem. Soc. 2015, 12, 765–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zainudin, E.S.; Abdul, S.; Yamani, K.; Alamery, S.; Fouad, H.; Santulli, C. Thermal and acoustic properties of silane and hydrogen peroxide treated oil palm/bagasse fiber based biophenolic hybrid composites. Polym. Compos. 2022, 43, 5954–5966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.Z.; Taghavian, H.; Zhang, X.; Militky, J.; Ali, A.; Wiener, J.; Tun, V.; Venkataraman, M.; Dvorak, L. Highly stable, flexible, anticorrosive coating of metalized nonwoven textiles for durable EMI shielding and thermal properties. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 8127–8139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, P.; Rurali, R. Thermal conductivity of rutile and anatase TiO2 from first-principles. J. Phys. Chem. C 2019, 123, 30851–30855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirposhteh, E.A.; Mortazavi, S.B.; Dehghan, S.F.; Khaloo, S.S.; Montazer, M. Optimization and development of workwear fabric coated with TiO2 nanoparticles in order to improve thermal insulation properties and air permeability. J. Ind. Text. 2024, 54, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakdel, E.; Naebe, M.; Kashi, S.; Cai, Z.; Xie, W.; Chun, A.; Yuen, Y.; Montazer, M.; Sun, L.; Wang, X. Functional cotton fabric using hollow glass microspheres: Focus on thermal insulation, flame retardancy, UV-protection and acoustic performance. Prog. Org. Coat. 2020, 141, 105553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orjuela-garz, I.C.; Rodr, C.F.; Cruz, J.C.; Bricen, J.C. Design, characterization, and evaluation of textile systems and coatings for sports use: Applications in the design of high-thermal comfort wearables. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 49143–49162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghezal, I.; Moussa, A.; Ben Marzoug, I.; El-Achari, A.; Campagne, C.; Sakli, F. Investigating waterproofness and breathability of a coated double-sided knitted fabric. Coatings 2022, 12, 1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Kremenakova, D.; Wang, Y.; Militky, J.; Mishra, R. Study on air permeability and thermal resistance of textiles under heat convection. Text. Res. J. 2015, 85, 1681–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, J.; Mazari, A.; Volesky, L.; Mazari, F. Effect of nano silver coating on thermal protective performance of firefighter protective clothing. J. Text. Inst. 2019, 110, 847–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babaeipour, S.; Nousiainen, P.; Kimiaei, E.; Tienaho, J.; Kohlhuber, N.; Korpinen, R.; Kaipanen, K.; Österberg, M. Thin multifunctional coatings for textiles based on the layer-by-layer application of polyaromatic hybrid nanoparticles. Mater. Adv. 2024, 5, 6114–6131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, H.R.; Kim, J.; Park, C.H. Facile fabrication of multifunctional fabrics: Use of copper and silver nanoparticles for antibacterial, superhydrophobic, conductive fabrics. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 41782–41794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample Code | TPOT Volume (mL/L) |

|---|---|

| Pristine PET | 0 |

| S1 | 30 |

| S2 | 60 |

| S3 | 90 |

| Sample | Initial Decomposition Temp. (°C) | Final Decomposition Temp. (°C) | Residue at 700 °C (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pristine PET | 428 | 543 | 1.6 |

| S1 | 438 | 561 | 11.6 |

| S2 | 441 | 603 | 30.5 |

| S3 | 437 | 599 | 46.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Khan, M.Z.; Ali, A.; Taghavian, H.; Wiener, J.; Militky, J.; Křemenáková, D. Surface Engineering of PET Fabrics with TiO2 Nanoparticles for Enhanced Antibacterial and Thermal Properties in Medical Textiles. Textiles 2025, 5, 71. https://doi.org/10.3390/textiles5040071

Khan MZ, Ali A, Taghavian H, Wiener J, Militky J, Křemenáková D. Surface Engineering of PET Fabrics with TiO2 Nanoparticles for Enhanced Antibacterial and Thermal Properties in Medical Textiles. Textiles. 2025; 5(4):71. https://doi.org/10.3390/textiles5040071

Chicago/Turabian StyleKhan, Muhammad Zaman, Azam Ali, Hadi Taghavian, Jakub Wiener, Jiri Militky, and Dana Křemenáková. 2025. "Surface Engineering of PET Fabrics with TiO2 Nanoparticles for Enhanced Antibacterial and Thermal Properties in Medical Textiles" Textiles 5, no. 4: 71. https://doi.org/10.3390/textiles5040071

APA StyleKhan, M. Z., Ali, A., Taghavian, H., Wiener, J., Militky, J., & Křemenáková, D. (2025). Surface Engineering of PET Fabrics with TiO2 Nanoparticles for Enhanced Antibacterial and Thermal Properties in Medical Textiles. Textiles, 5(4), 71. https://doi.org/10.3390/textiles5040071