Full-Field In-Plane Tensile Characterization of Cotton Fabrics Using 2D Digital Image Correlation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- The sample is presumably planar. This presumption holds for initially flat specimens with or without geometric discontinuities (such as cracks, notches, or cut-outs) or gradients in material characteristics.

- The camera sensor plane and the sample plane are parallel. A nominally planar object is considered to be subjected to a combination of in-plane tension, in-plane shear, or in-plane biaxial loading so that the sample primarily deforms inside the original planar surface. Poisson’s effect in the crack tip region (which causes slight out-of-plane motion) is expected to be minimal in comparison to the applied in-plane deformations when cracked or notched specimens are loaded.

- The loaded sample is deformed only in the original plane.

2.1. Statistics

2.1.1. Maximum Force and Elongation Recorded on Tensile Testing Machine

- Factor A: Type of fabric (Fabric 1, Fabric 2, Fabric 3)

- Factor B: Specimen orientation (warp vs. weft)

2.1.2. Strain Values Obtained by DIC Measurement

- The main effect of Fabric type on strain values;

- The main effect of Orientation (warp vs. weft);

- The potential interaction between Fabric type and Orientation.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. ANOVA Results for Maximum Force and Elongation

- Effect of Fabric: There was a clear distinction among the three tested fabrics in terms of maximum force.

- Effect of Orientation (warp vs. weft): Across all fabrics, warp-oriented specimens exhibited higher average tensile strength, although the degree of this difference varied from one fabric to another.

- Interaction Between Fabric and Orientation: A significant Fabric × Orientation interaction (p < 0.05) indicates that the impact of orientation is not uniform across all fabrics. For instance, Fabric 3 displayed a considerably larger discrepancy between warp and weft (over 250 N difference on average), whereas Fabric 2 showed only a moderate divergence between these two orientations.

- Effect of Fabric: The extremely low p-value indicates a statistically significant difference among Fabric 1, Fabric 2, and Fabric 3 in terms of elongation.

- Effect of Orientation: This finding confirms that warp vs. weft orientation strongly influences the observed elongation values.

- Fabric × Orientation Interaction: A significant interaction suggests that the difference between warp and weft elongation depends on the specific fabric being tested.

3.2. ANOVA Results for EpsX and EpsY

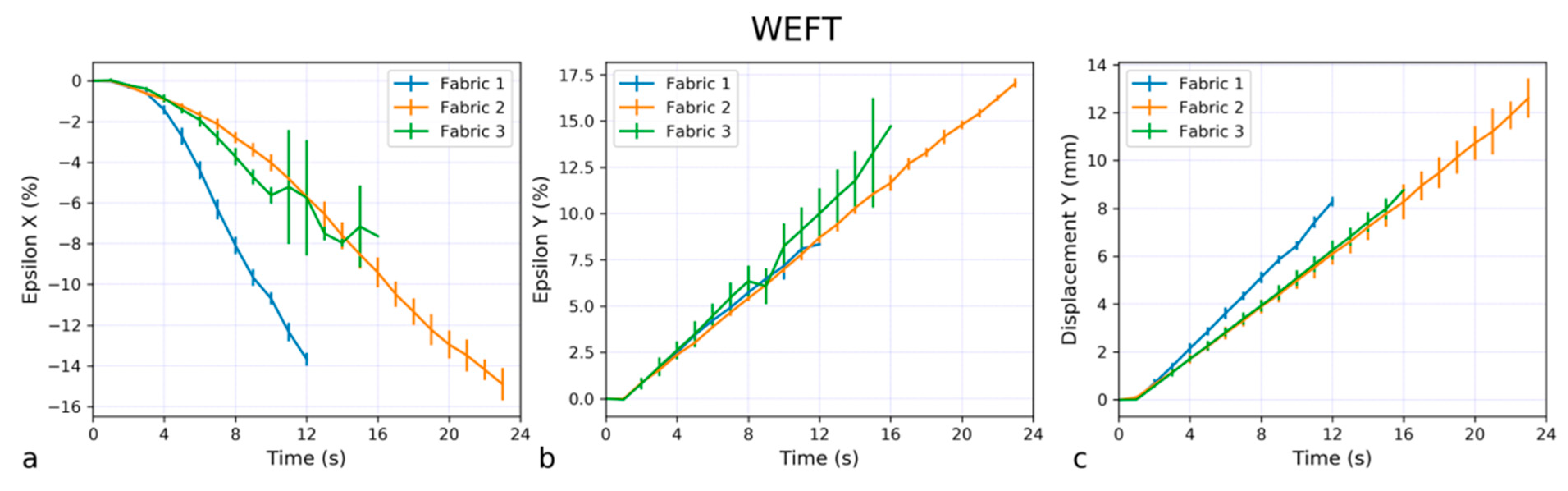

- Fabric type significantly affects both EpsX and EpsY (p < 0.001). Fabric 2 exhibited the highest EpsY values, while Fabric 3 had the lowest. This suggests that Fabric 2 is structurally more flexible in the y-direction, potentially due to differences in weave density, fiber composition, or finishing processes.

- Orientation has a significant effect on EpsY (p < 0.001), but not on EpsX (p = 0.193). This indicates that strain in the y-direction is more dependent on fiber orientation than strain in the x-direction. This could be due to anisotropic behavior in the weave structure, where fibers aligned in the y-direction experience higher deformations under loading.

- The interaction between Fabric and Orientation is significant for both EpsX and EpsY, suggesting that the influence of orientation on strain varies depending on the fabric type. For instance:

- -

- Fabric 1 shows minimal differences between warp and weft, indicating a more balanced mechanical response in both directions.

- -

- Fabric 2 and Fabric 3 exhibit pronounced differences between warp and weft, meaning that their strain response is orientation-dependent.

- -

- EpsX is significantly lower for Fabric 2 in the weft direction, whereas EpsY is significantly higher for Fabric 2 in the weft direction. This suggests that Fabric 2 undergoes more elongation in the y-direction while resisting deformation in the x-direction.

- Fabric 1 and Fabric 2 did not significantly differ in warp orientation, but in weft orientation, Fabric 2 had significantly lower EpsX than Fabric 1.

- Fabric 3 exhibited the highest EpsX values, with significant differences from both Fabric 1 and Fabric 2 in most comparisons. This implies that Fabric 3 may have a lower stiffness in the x-direction, possibly due to its fiber arrangement or lower thread density in the warp direction.

- The difference between warp and weft orientations was only significant for Fabric 2, where EpsX was lower in the weft direction.

- Fabric 2 showed significantly higher EpsY compared to Fabric 1 and Fabric 3.

- The difference between warp and weft was statistically significant across most groups, reinforcing the idea that EpsY is more sensitive to fiber orientation than EpsX

- The largest difference was observed between Fabric 2 (weft) and Fabric 3 (warp), with a mean difference of 10.61 (p < 0.001), confirming the pronounced effect of both Fabric type and Orientation on strain in the y-direction. The post hoc test further reveals that for Fabric 2 and Fabric 3, EpsY is significantly higher in the weft direction than in the warp direction. This suggests that these fabrics allow more deformation perpendicular to the warp fibers, likely due to differences in crimp or fiber flexibility.

3.3. Comparison of ANOVA Results from Tensile Testing and DIC Analysis

- DIC reveals deformation anisotropy at an earlier stage.

- ○

- Tensile testing shows that orientation influences maximum elongation, but DIC shows that EpsY (strain in the loading direction) is more orientation-sensitive than EpsX.

- ○

- This suggests that DIC enables a deeper understanding of fiber interactions within the weave.

- DIC identifies strain concentration zones before failure.

- ○

- In tensile testing, failure is recorded at the moment of specimen rupture, with no information on how the deformation evolved prior to breaking.

- ○

- DIC enables continuous strain monitoring, allowing detection of early damage accumulation, which can be critical for applications requiring long-term durability.

- DIC captures lateral deformation that tensile tests cannot detect.

- ○

- Tensile testing only records elongation in the loading direction.

- ○

- DIC provides information on strain perpendicular to the loading direction (EpsX), which reveals lateral strain redistribution that may be crucial for understanding material ductility and flexibility.

- DIC is essential for fabrics with complex structural responses.

- ○

- The significant Fabric × Orientation interaction effect in both EpsX and EpsY suggests that some fabrics exhibit non-uniform deformation.

- ○

- This complex behavior is difficult to interpret from tensile force and elongation alone, but DIC makes it quantifiable.

4. Conclusions

- DIC reveals microstructural strain evolution, offering insights beyond global elongation measurements.

- The differences in ANOVA outcomes highlight that DIC captures deformation anisotropy that is not apparent in tensile testing.

- By analyzing both EpsX and EpsY, DIC provides a more complete picture of how fabrics accommodate strain, redistributing stresses within their structure.

- The combination of tensile testing and DIC enables a multi-scale understanding of textile behavior, making it an essential tool for optimizing fabric performance in structural applications.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Group1 | Group2 | Meandiff | p-adj | Lower | Upper | Reject |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fabric1_Warp | Fabric1_Weft | −20.6667 | 0.9823 | −124.4535 | 83.1201 | False |

| Fabric1_Warp | Fabric2_Warp | −3.6667 | 1.0 | −107.4535 | 100.1201 | False |

| Fabric1_Warp | Fabric2_Weft | 35.6667 | 0.8495 | −68.1201 | 139.4535 | False |

| Fabric1_Warp | Fabric3_Warp | 2.6667 | 1.0 | −101.1201 | 106.4535 | False |

| Fabric1_Warp | Fabric3_Weft | −256.6667 | 0.0 | −360.4535 | −152.8799 | True |

| Fabric1_Weft | Fabric2_Warp | 17.0 | 0.9926 | −86.7868 | 120.7868 | False |

| Fabric1_Weft | Fabric2_Weft | 56.3333 | 0.4874 | −47.4535 | 160.1201 | False |

| Fabric1_Weft | Fabric3_Warp | 23.3333 | 0.9702 | −80.4535 | 127.1201 | False |

| Fabric1_Weft | Fabric3_Weft | −236.0 | 0.0001 | −339.7868 | −132.2132 | True |

| Fabric2_Warp | Fabric2_Weft | 39.3333 | 0.7936 | −64.4535 | 143.1201 | False |

| Fabric2_Warp | Fabric3_Warp | 6.3333 | 0.9999 | −97.4535 | 110.1201 | False |

| Fabric2_Warp | Fabric3_Weft | −253.0 | 0.0 | −356.7868 | −149.2132 | True |

| Fabric2_Weft | Fabric3_Warp | −33.0 | 0.8849 | −136.7868 | 70.7868 | False |

| Fabric2_Weft | Fabric3_Weft | −292.3333 | 0.0 | −396.1201 | −188.5465 | True |

| Fabric3_Warp | Fabric3_Weft | −259.3333 | 0.0 | −363.1201 | −155.5465 | True |

Appendix B

| Group1 | Group2 | Meandiff | p-adj | Lower | Upper | Reject |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fabric1_Warp | Fabric1_Weft | −0.0833 | 0.9998 | −1.2211 | 1.0544 | False |

| Fabric1_Warp | Fabric2_Warp | 5.3 | 0.0 | 4.1622 | 6.4378 | True |

| Fabric1_Warp | Fabric2_Weft | 9.88 | 0.0 | 8.7422 | 11.0178 | True |

| Fabric1_Warp | Fabric3_Warp | −2.3 | 0.0002 | −3.4378 | −1.1622 | True |

| Fabric1_Warp | Fabric3_Weft | 2.6967 | 0.0 | 1.5589 | 3.8344 | True |

| Fabric1_Weft | Fabric2_Warp | 5.3833 | 0.0 | 4.2456 | 6.5211 | True |

| Fabric1_Weft | Fabric2_Weft | 9.9633 | 0.0 | 8.8256 | 11.1011 | True |

| Fabric1_Weft | Fabric3_Warp | −2.2167 | 0.0003 | −3.3544 | −1.0789 | True |

| Fabric1_Weft | Fabric3_Weft | 2.78 | 0.0 | 1.6422 | 3.9178 | True |

| Fabric2_Warp | Fabric2_Weft | 4.58 | 0.0 | 3.4422 | 5.7178 | True |

| Fabric2_Warp | Fabric3_Warp | −7.6 | 0.0 | −8.7378 | −6.4622 | True |

| Fabric2_Warp | Fabric3_Weft | −2.6033 | 0.0001 | −3.7411 | −1.4656 | True |

| Fabric2_Weft | Fabric3_Warp | −12.18 | 0.0 | −13.3178 | −11.0422 | True |

| Fabric2_Weft | Fabric3_Weft | −7.1833 | 0.0 | −8.3211 | −6.0456 | True |

| Fabric3_Warp | Fabric3_Weft | 4.9967 | 0.0 | 3.8589 | 6.1344 | True |

Appendix C

| Group1 | GROUP2 | Meandiff | p-adj | Lower | Upper | Reject |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fabric1_Warp | Fabric1_Weft | −0.0943 | 1.0 | −1.986 | 1.7973 | False |

| Fabric1_Warp | Fabric2_Warp | 0.1673 | 0.9996 | −1.7243 | 2.059 | False |

| Fabric1_Warp | Fabric2_Weft | −1.8967 | 0.0493 | −3.7883 | −0.005 | True |

| Fabric1_Warp | Fabric3_Warp | 4.1067 | 0.0001 | 2.215 | 5.9983 | True |

| Fabric1_Warp | Fabric3_Weft | 4.9197 | 0.0 | 3.028 | 6.8113 | True |

| Fabric1_Weft | Fabric2_Warp | 0.2617 | 0.9966 | −1.63 | 2.1533 | False |

| Fabric1_Weft | Fabric2_Weft | −1.8023 | 0.0651 | −3.694 | 0.0893 | False |

| Fabric1_Weft | Fabric3_Warp | 4.201 | 0.0001 | 2.3094 | 6.0926 | True |

| Fabric1_Weft | Fabric3_Weft | 5.014 | 0.0 | 3.1224 | 6.9056 | True |

| Fabric2_Warp | Fabric2_Weft | −2.064 | 0.0299 | −3.9556 | −0.1724 | True |

| Fabric2_Warp | Fabric3_Warp | 3.9393 | 0.0002 | 2.0477 | 5.831 | True |

| Fabric2_Warp | Fabric3_Weft | 4.7523 | 0.0 | 2.8607 | 6.644 | True |

| Fabric2_Weft | Fabric3_Warp | 6.0033 | 0.0 | 4.1117 | 7.895 | True |

| Fabric2_Weft | Fabric3_Weft | 6.8163 | 0.0 | 4.9247 | 8.708 | True |

| Fabric3_Warp | Fabric3_Weft | 0.813 | 0.7026 | −1.0786 | 2.7046 | False |

Appendix D

| Group1 | Group2 | Meandiff | p-adj | Lower | Upper | Reject |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fabric1_Warp | Fabric1_Weft | −0.4187 | 0.9944 | −3.1332 | 2.2959 | False |

| Fabric1_Warp | Fabric2_Warp | 5.5127 | 0.0002 | 2.7981 | 8.2272 | True |

| Fabric1_Warp | Fabric2_Weft | 8.166 | 0.0 | 5.4515 | 10.8805 | True |

| Fabric1_Warp | Fabric3_Warp | −2.4407 | 0.0876 | −5.1552 | 0.2739 | False |

| Fabric1_Warp | Fabric3_Weft | 3.7333 | 0.006 | 1.0188 | 6.4479 | True |

| Fabric1_Weft | Fabric2_Warp | 5.9313 | 0.0001 | 3.2168 | 8.6459 | True |

| Fabric1_Weft | Fabric2_Weft | 8.5847 | 0.0 | 5.8701 | 11.2992 | True |

| Fabric1_Weft | Fabric3_Warp | −2.022 | 0.1979 | −4.7365 | 0.6925 | False |

| Fabric1_Weft | Fabric3_Weft | 4.152 | 0.0026 | 1.4375 | 6.8665 | True |

| Fabric2_Warp | Fabric2_Weft | 2.6533 | 0.0567 | −0.0612 | 5.3679 | False |

| Fabric2_Warp | Fabric3_Warp | −7.9533 | 0.0 | −10.6679 | −5.2388 | True |

| Fabric2_Warp | Fabric3_Weft | −1.7793 | 0.3041 | −4.4939 | 0.9352 | False |

| Fabric2_Weft | Fabric3_Warp | −10.6067 | 0.0 | −13.3212 | −7.8921 | True |

| Fabric2_Weft | Fabric3_Weft | −4.4327 | 0.0015 | −7.1472 | −1.7181 | True |

| Fabric3_Warp | Fabric3_Weft | 6.174 | 0.0001 | 3.4595 | 8.8885 | True |

References

- Anand, S.C.; Kennedy, J.F.; Miraftab, M.; Rajendran, S. (Eds.) Medical and Healthcare Textiles; Woodhead Publishiag Limited: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Asanovic, K.; Cerovic, D.; Mihailovic, T.; Kostic, M.M.; Reljic, M. Quality of clothing fabrics in terms of their comfort properties. Indian J. Fibre Text. Res. 2015, 40, 363–372. [Google Scholar]

- Reljic, M.; Stojiljkovic, S.; Stepanovic, J.; Lazic, B.; Stojiljkovic, M. Study of Water Vapor Resistance of Co/PES Fabrics Properties During Maintenance. In Experimental and Numerical Investigations in Materials Science and Engineering; Mitrovic, N., Milosevic, M., Mladenovic, G., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 72–83. [Google Scholar]

- Reljić, M.; Lazić, B.; Stepanović, J.; Dordić, D. Thermophysiological properties of knitted fabrics for sports underwear. Struct. Integr. Life 2017, 17, 145–149. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J. Structure and Mechanics of Woven Fabrics; Woodhead Publishing Limited: Cambridge, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Klinge, U.; Otto, J.; Mühl, T. High structural stability of textile implants prevents pore collapse and preserves effective porosity at strain. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 1, 953209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, A.A.; Shahid, M.; Siddiqui, N.A.; Nawab, Y.; Iqbal, M. Effect of Geometric Arrangement on Mechanical Properties of 2D Woven Auxetic Fabrics. Textiles 2022, 2, 606–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadi, H.; Uhlemann, J.; Stranghoener, N.; Ulbricht, M. Mechanical Property Characterization of Architectural Coated Woven Fabrics Subjected to Freeze–Thaw Cycles. Textiles 2024, 4, 26–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, K.; Newman, Z.; West, A.; Lee, K.L.; Rokkam, S. Efficient Poisson’s Ratio Evaluation of Weft-Knitted Auxetic Metamaterials. Textiles 2023, 3, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penava, Ž.; Penava, D.Š.; Knezić, Ž. Determination of the Elastic Constants of Plain Woven Fabrics by a Tensile Test in Various Directions. Fibres Text. East. Eur. 2014, 22, 57–63. [Google Scholar]

- Wilusz, E. Military Textiles; Woodhead Publishing Limited: Cambridge, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, J.; Takatera, M.; Inui, S.; Shimizu, Y. Measuring Technology of the Anisotropic Tensile Properties of Woven Fabrics. Text. Res. J. 2008, 78, 1116–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hursa, A.; Rolich, T.; Ercegovic Razic, S. Determining Pseudo Poisson’s Ratio of Woven Fabric with a Digital Image Correlation Method. Text. Res. J. 2009, 79, 1588–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meskuotiene, A.; Dargiene, J.; Domskiene, J. Metrological performance of the digital image analysis method applied for investigation of textile deformation. Text. Res. J. 2015, 85, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazimoradi, M.; Carvelli, V.; Marchesi, M.C.; Frassine, R. Mechanical characterization of tetraxial textiles. J. Ind. Text. 2018, 48, 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boisse, P.; Hamila, N.; Guzman-Maldonado, E.; Madeo, A.; Hivet, G.; dell’Isola, F. The bias-extension test for the analysis of in-plane shear properties of textile composite reinforcements and prepregs: A review. Int. J. Mater. Form. 2017, 10, 473–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, M.A.; Orteu, J.-J.; Hubert, W.S. Image Correlation for Shape, Motion and Deformation Measurements: Basic Concepts, Theory and Applications; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitrović, N.; Golubović, Z.; Mitrović, A.; Travica, M.; Trajković, I.; Milošević, M.; Petrović, A. Influence of Aging on the Flexural Strength of PLA and PLA-X 3D-Printed Materials. Micromachines 2024, 15, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitrović, N.; Mitrović, A.; Travica, M. Tensile Testing of Flat Thin Specimens Using the Two-Dimensional Digital Image Correlation Method. Struct. Integr. Life 2023, 23, 9–13. [Google Scholar]

- EN ISO 13934; Textiles—Tensile Properties of Fabrics—Part 1: Determination of Maximum Force and Elongation at Maximum Force Using the Strip Method. The International Organization for Standardization ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013.

- Lomov, S.V.; Boisse, P.; Deluycker, E.; Morestin, F.; Vanclooster, K.; Vandepitte, D.; Verpoest, I.; Willems, A. Full-field strain measurements in textile deformability studies. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2008, 39, 1232–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Q.; Chen, L.; Wang, W.; Zhang, C. Study on tensile properties of carbon fiber/epoxy laminated woven composites with ply splicing. J. Ind. Text. 2022, 52, 1528083722113630752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, L.; Guo, N.; Xu, H.; Jiang, J.; Zhang, T.; Chen, N. Tensile characteristics of flexible PU-coated multi-axial warp-knitted fabrics. J. Ind. Text. 2017, 47, 38–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitrovic, N.; Mitrovic, A.; Reljic, M. Strain measurement of medical textile using 2d digital image correlation method. Lect. Notes Netw. Syst. 2021, 153, 447–464. [Google Scholar]

| Number of Threads per Unit Length, Threads-cm | Fiber Composition | Mass per Unit Area, g/m2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fabric 1 | Warp | 47.2 | 78.9% cotton 21.1% polyester | 107.6 |

| Weft | 25.0 | |||

| Fabric 2 | Warp | 33.1 | 100% cotton (combed) | 124.4 |

| Weft | 30.0 | |||

| Fabric 3 | Warp | 52.6 | 100% cotton (mercerized) | 126.5 |

| Weft | 30.0 | |||

| Maximum Mean Force, N | Standard Deviation, N | Mean Elongation, % | Standard Deviation, % | Mean Poisson Coefficient,/ | Standard Deviation,/ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fabric 1 | Warp | 579 | 47.4 | 9.40 | 0.527 | 1.450 | 0.034 |

| Weft | 559 | 29.2 | 9.32 | 0.465 | 1.475 | 0.024 | |

| Fabric 2 | Warp | 576 | 7.40 | 14.7 | 0.200 | 0.881 | 0.018 |

| Weft | 615 | 19.2 | 19.3 | 0.270 | 0.788 | 0.022 | |

| Fabric 3 | Warp | 582 | 66.3 | 7.10 | 0.515 | 1.379 | 0.009 |

| Weft | 328 | 25.5 | 12.1 | 0.404 | 0.720 | 0.017 | |

| Source of Variation | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Maximum Force | Elongation | |

| Fabric (A) | 0.0000607 | 5.54 × 10−13 |

| Orientation (B) | 0.0007306 | 1.63 × 10−9 |

| Interaction (A × B) | 0.0000423 | 2.55 × 10−7 |

| Source of Variation | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|

| EpsX | EpsY | |

| Fabric | 2.37 × 10−8 | 5.73 × 10−8 |

| Orientation | 0.193 | 6.15 × 10−5 |

| Fabric × Orientation | 0.0105 | 3.44 × 10−4 |

| Parameter | Fabric Effect (p-Value) | Orientation Effect (p-Value) | Interaction Effect (p-Value) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum Force | p < 0.001 (Significant) | p < 0.001 (Significant) | p < 0.001 (Significant) |

| Elongation (%) | p < 0.001 (Significant) | p < 0.001 (Significant) | p < 0.001 (Significant) |

| EpsX (DIC) | p < 0.001 (Significant) | p = 0.193 (Not Significant) | p = 0.011 (Significant) |

| EpsY (DIC) | p < 0.001 (Significant) | p < 0.001 (Significant) | p < 0.001 (Significant) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mitrovic, N.; Mitrovic, A.; Reljic, M.; Pelemis, S. Full-Field In-Plane Tensile Characterization of Cotton Fabrics Using 2D Digital Image Correlation. Textiles 2025, 5, 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/textiles5040067

Mitrovic N, Mitrovic A, Reljic M, Pelemis S. Full-Field In-Plane Tensile Characterization of Cotton Fabrics Using 2D Digital Image Correlation. Textiles. 2025; 5(4):67. https://doi.org/10.3390/textiles5040067

Chicago/Turabian StyleMitrovic, Nenad, Aleksandra Mitrovic, Mirjana Reljic, and Svetlana Pelemis. 2025. "Full-Field In-Plane Tensile Characterization of Cotton Fabrics Using 2D Digital Image Correlation" Textiles 5, no. 4: 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/textiles5040067

APA StyleMitrovic, N., Mitrovic, A., Reljic, M., & Pelemis, S. (2025). Full-Field In-Plane Tensile Characterization of Cotton Fabrics Using 2D Digital Image Correlation. Textiles, 5(4), 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/textiles5040067