Notes on Winter Bat Mortality, Hibernation Preferences, and the Demographic Structure of Deceased Individuals from One of Europe’s Largest Bat Colonies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

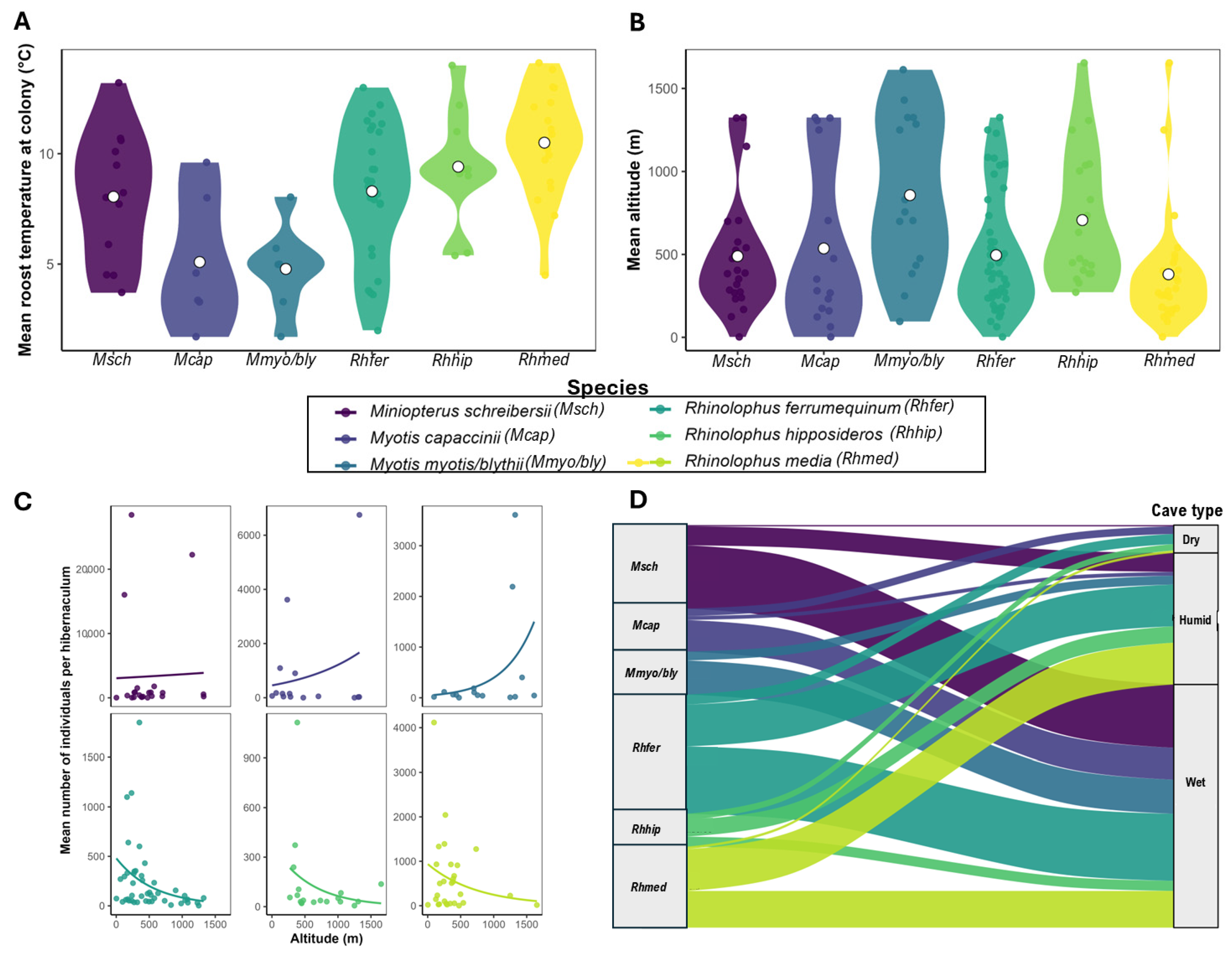

2.1. Hibernacula Survey and Hibernation Site Characteristics

2.2. Bat Sampling

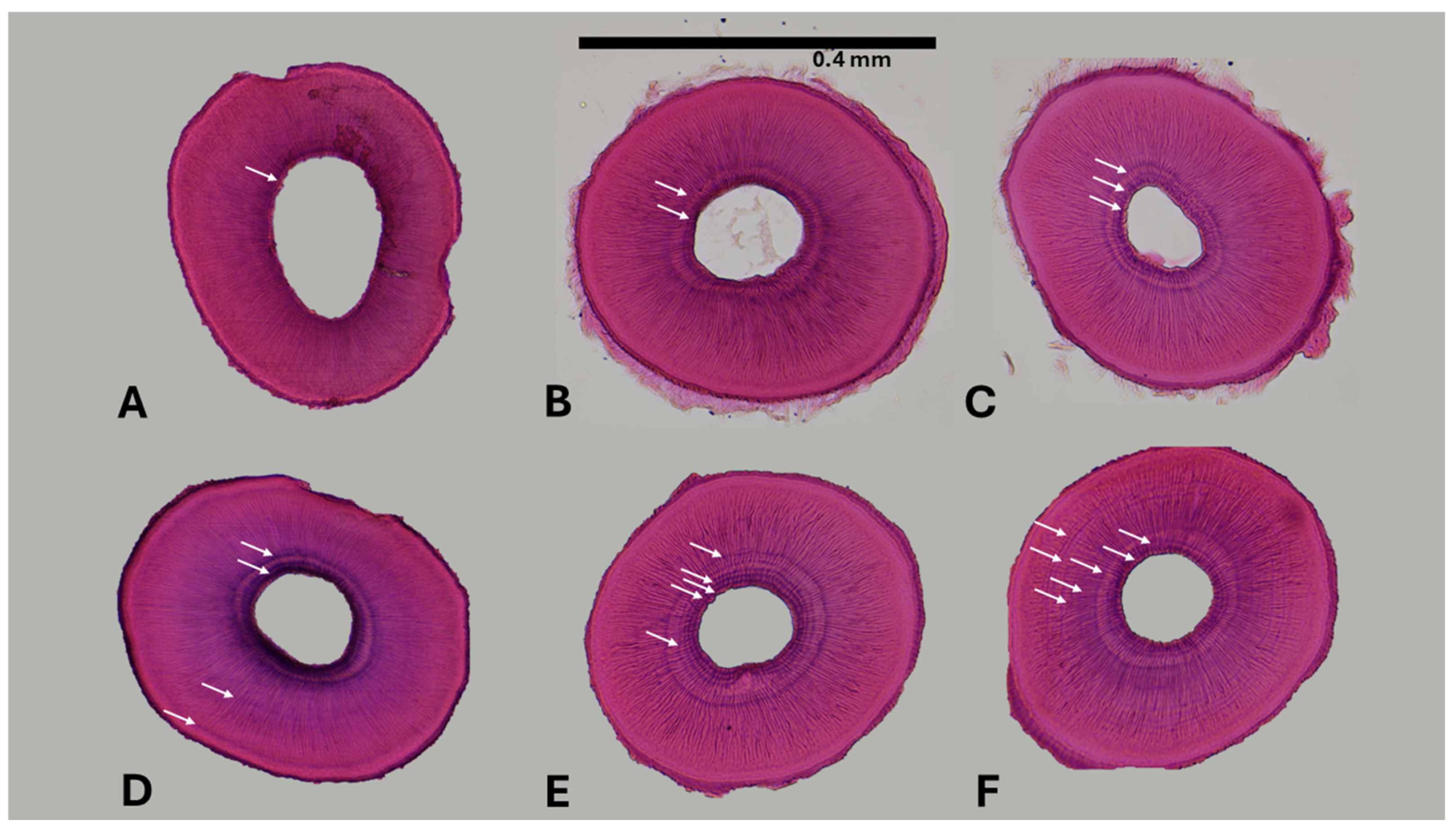

2.3. Laboratory Processing and Age Determination

2.4. Data Processing and Statistical Analyses

2.4.1. Unusual Mortality Event

2.4.2. Species-Specific Hibernation Preferences

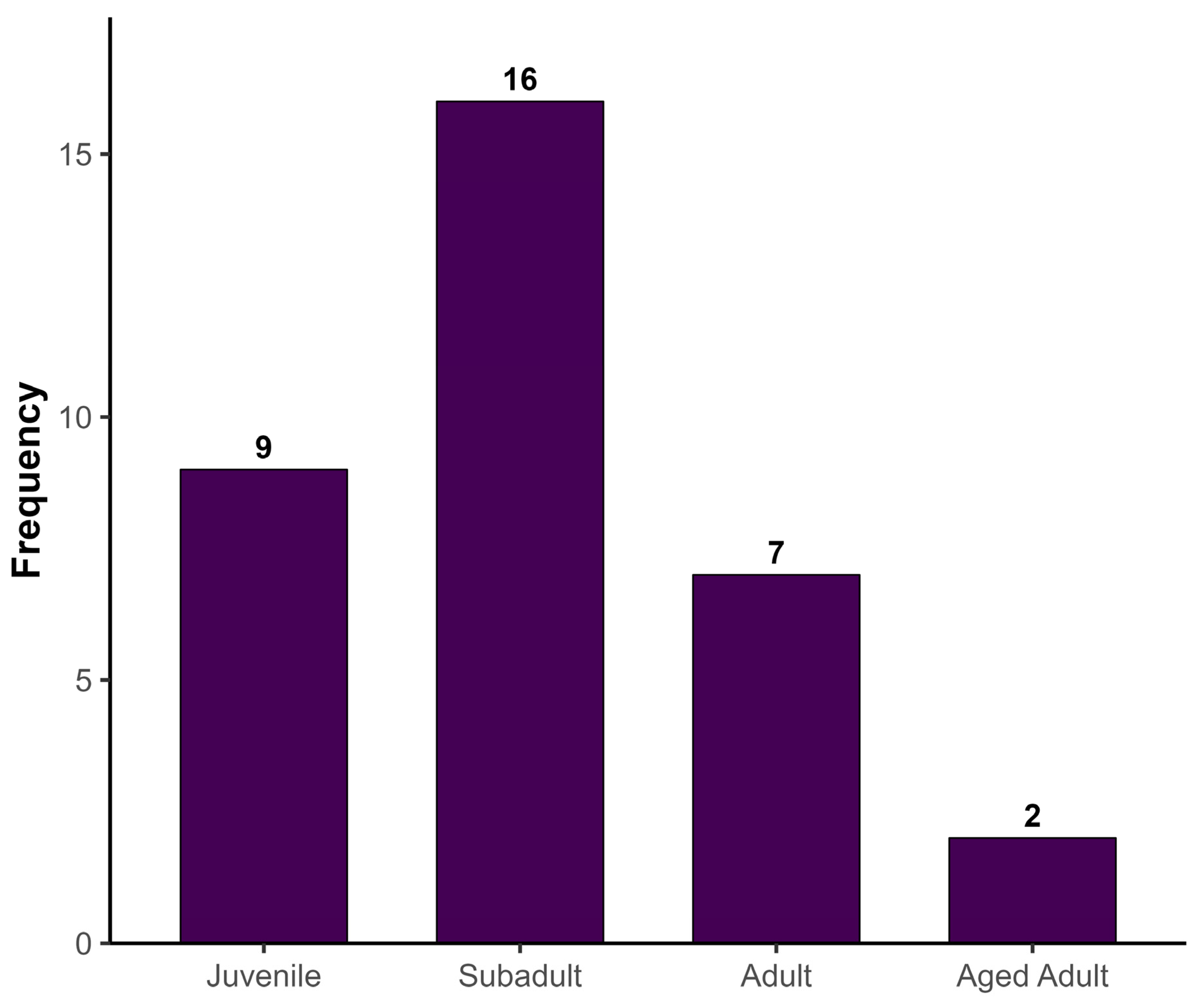

2.4.3. Age-Structure Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- O’Shea, T.J.; Ellison, L.E.; Stanley, T.R. Survival estimation in bats: Historical overview, critical appraisal and suggestions for new approaches. In Sampling Rare or Elusive Species: Concepts, Designs, and Techniques for Estimating Population Parameters; Thompson, W.L., Ed.; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2004; pp. 297–336. [Google Scholar]

- Touzalin, F.; Petit, É.; Cam, E.; Stagier, C.; Teeling, E.C.; Puechmaille, S.J. Mark loss can strongly bias estimates of demographic rates in multi-state models: A case study with simulated and empirical datasets. Peer Community J. 2023, 3, e348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blehert, D.S.; Hicks, A.C.; Behr, M.; Meteyer, C.U.; Berlowski-Zier, B.M.; Buckles, E.L.; Coleman, J.T.H.; Darling, S.R.; Gargas, A.; Niver, R.; et al. Bat white-nose syndrome: An emerging fungal pathogen? Science 2009, 323, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fritze, M.; Puechmaille, S.J. Identifying unusual mortality events in bats: A baseline for bat hibernation monitoring and white-nose syndrome research. Mammal Rev. 2018, 48, 224–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Shea, T.J.; Cryan, P.M.; Hayman, D.T.S.; Plowright, R.K.; Streicker, D.G. Multiple mortality events in bats: A global review. Mammal Rev. 2016, 46, 175–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vindenes, Y.; Langangen, Ø. Individual heterogeneity in life histories and eco-evolutionary dynamics. Ecol. Lett. 2015, 18, 417–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, R.D.; Muradali, F.; Lázaro, L. Age composition of vampire bats (Desmodus rotundus) in northern Argentina and southern Brazil. J. Mammal. 1976, 57, 573–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schowalter, D.B.; Harder, L.D.; Treichel, B.H. Age composition of some vespertilionid bats as determined by dental annuli. Can. J. Zool. 1978, 56, 355–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunet-Rossinni, A.K.; Austad, S.N. Ageing studies on bats: A review. Biogerontology 2004, 5, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batulevicius, D.; Paužienė, N.; Pauža, D.H. Dental incremental lines in some small species of the European vespertilionid bats. Acta Theriol. 2001, 46, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunet-Rossini, A.K.; Wilkinson, G. Methods for estimating age in bats. In Ecological and Behavioral Methods for the Study of Bats, 2nd ed.; Kunz, T.H., Parsons, S., Eds.; The Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2009; pp. 315–326. [Google Scholar]

- Toshkova, N.; Brosens, D.; Stoeva, E.; Deleva, S.; Zhelyazkova, V.; Acosta-Pankov, I.; Goranov, S.; Dundarova, H.; Lakovski, K.; Genova, O.; et al. Bat Occurrences from Bulgaria, Version 1.5; National Museum of Natural History, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2025; Occurrence Download. Available online: https://doi.org/10.15468/dnu63p (accessed on 10 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Bulgarian Federation of Speleology. Bulgarian Cave Database. Available online: https://caves.speleo-bg.org/ (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Dietz, C.; von Helversen, O. Illustrated Identification Key to the Bats of Europe; Dietz & von Helversen: Tübingen, Germany, 2004; Volume 1, pp. 1–74. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanova, T. Important bat underground habitats (IBuH) in Bulgaria. Acta Zool. Bulg. 2005, 57, 197–206. [Google Scholar]

- Deleva, S.; Toshkova, N.; Kolev, M.; Tanalgo, K.C. Important underground roosts for bats in Bulgaria: Current state and priorities for conservation. Biodivers. Data J. 2023, 11, e98734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Shea, T.J.; Ellison, L.E.; Stanley, T.R. Adult survival and population growth rate in Colorado big brown bats (Eptesicus fuscus). J. Mammal. 2011, 92, 433–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barclay, R.; Harder, L. Life Histories of Bats: Life in the Slow Lane. In Bat Ecology; Kunz, T.H., Fenton, M.B., Eds.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2003; pp. 209–253. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanova, T.; Petrov, B. A new stage in bat (Chiroptera) research in Bulgaria. Hist. Nat. Bulg. 2001, 13, 88. (In Bulgarian) [Google Scholar]

- López-Baucells, A.; López-Bosch, D.; Blanch, E.; Hamidovic, D.; Ortega Castaño, A.; Aihartza, J.; Aulagnier, S.; Bartonicka, T.; Bas, Y.; Bellè, A.; et al. Bat Monitoring Programmes and Protocols for European Bats, Version 1.0.0.; Zenodo: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Fleischer, T.; Gampe, J.; Scheuerlein, A.; Kerth, G. Rare catastrophic events drive population dynamics in a bat species with negligible senescence. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 6298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Roig, M.; Piera, E.; Serra-Cobo, J. Thinner bats to face hibernation as response to climate warming. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernard, R.F.; Willcox, E.V.; Jackson, R.T.; Brown, V.A.; McCracken, G.F. Feasting, not fasting: Winter diets of cave hibernating bats in the United States. Front. Zool. 2021, 18, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toshkova, N.; Dimitrova, K.; Langourov, M.; Zlatkov, B.; Bekchiev, R.; Ljubomirov, T.; Zielke, E.; Angelova, R.; Parvanova, R.; Simeonov, T.; et al. Snacking during hibernation? Winter bat diet and prey availabilities, a case study from Iskar Gorge, Bulgaria. Hist. Nat. Bulg. 2023, 45, 125–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constant, T.; Giroud, S.; Viblanc, V.A.; Tissier, M.L.; Bergeron, P.; Dobson, F.S.; Habold, C. Integrating mortality risk and the adaptiveness of hibernation. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medinas, D.; Ribeiro, V.; Barbosa, S.; Valerio, F.; Marques, J.T.; Rebelo, H.; Paupério, J.; Santos, S.; Mira, A. Fine scale genetics reveals the subtle negative effects of roads on an endangered bat. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 869, 161705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theimer, T.C.; Dyer, A.C.; Keeley, B.W.; Gilbert, A.T.; Bergman, D.L. Ecological potential for rabies virus transmission via scavenging of dead bats by mesocarnivores. J. Wildl. Dis. 2017, 53, 382–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente, J.; VerCauteren, K.C. The role of scavenging in disease dynamics. In Wildlife Research Monographs; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 161–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mühldorfer, K.; Speck, S.; Wibbelt, G. Diseases in free-ranging bats from Germany. BMC Vet. Res. 2011, 7, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sriraman, P. Wildlife Necropsy and Forensics; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombino, E.; Lelli, D.; Canziani, S.; Quaranta, G.; Guidetti, C.; Leopardi, S.; Robetto, S.; De Benedictis, P.; Orusa, R.; von Degerfeld, M.M.; et al. Main causes of death of free-ranging bats in Turin province (north-western Italy): Gross and histological findings and emergent virus surveillance. BMC Vet. Res. 2023, 19, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gol’din, P.; Godlevska, L.; Ghazali, M. Age-related changes in the teeth of two bat species: Dental wear, pulp cavity and dentine growth layers. Acta Chiropterolog. 2019, 20, 519–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toshkova, N.; Kolev, M.; Deleva, S.; Simeonov, T.; Popov, V. Winter is (not) coming: Acoustic monitoring and temperature variation across important bat hibernacula. Biodivers. Data J. 2025, 13, e141801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, C.J.; Steinberg, B.M.; Kunz, T.H. Dentin, cementum, and age determination in bats: A critical evaluation. J. Mammal. 1982, 63, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baagøe, H.J. Age determination in bats (Chiroptera). Videnskabelige Meddelelser fra. Dan. Naturhist. Foren. 1977, 140, 53–92. [Google Scholar]

- Cool, S.M.; Bennet, M.; Romaniuk, K. Age estimation of pteropodid bats (Megachiroptera) from hard tissue parameters. Wildl. Res. 1994, 21, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, G.S.; Adams, D.M.; Haghani, A.; Lu, A.T.; Zoller, J.A.; Breeze, C.E.; Arnold, B.D.; Ball, H.C.; Carter, G.G.; Cooper, L.N.; et al. DNA methylation predicts age and provides insight into exceptional longevity of bats. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, D.M.; Rayner, J.G.; Hex, S.B.S.W.; Wilkinson, G.S. DNA methylation dynamics reflect sex and status differences in mortality rates in a polygynous bat. Mol. Ecol. 2025, 34, 2331–2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sendor, T.; Simon, M. Population dynamics of the pipistrelle bat: Effects of sex, age and winter weather on seasonal survival. J. Anim. Ecol. 2003, 72, 308–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, M.I.; Fitzpatrick, S.W.; Bradburd, G.S. Pitfalls and windfalls of detecting demographic declines using population genetics in long-lived species. Evol. Appl. 2024, 17, e13754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gargiulo, R.; Budde, K.B.; Heuertz, M. Mind the lag: Understanding genetic extinction debt for conservation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2025, 40, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gamelon, M.; Gaillard, J.; Giménez, O.; Coulson, T.; Tuljapurkar, S.; Baubet, É. Linking demographic responses and life history tactics from longitudinal data in mammals. Oikos 2015, 125, 395–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Site | Total Visits | Years Covered | Notes (e.g., Multiple Visits per Year) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Devetashka | 14 | 1997–2024 | Several years with >1 visit |

| Parnicite (Dolen parnik) | 14 | 1996–2023 | Several years with >1 visit |

| Ivanova Voda | 6 | 1997–2022 | Surveyed every 2–3 years |

| Orlova Chuka | 12 | 1991–2022 | Several years with >1 visit |

| Pavla (Ravnogorskata Peshtera) | 4 | 2008–2014 | Occasional surveys |

| Skoka | 2 | 2008–2016 | Occasional surveys |

| Ponora | 7 | 2012–2022 | Surveyed every 2–3 years |

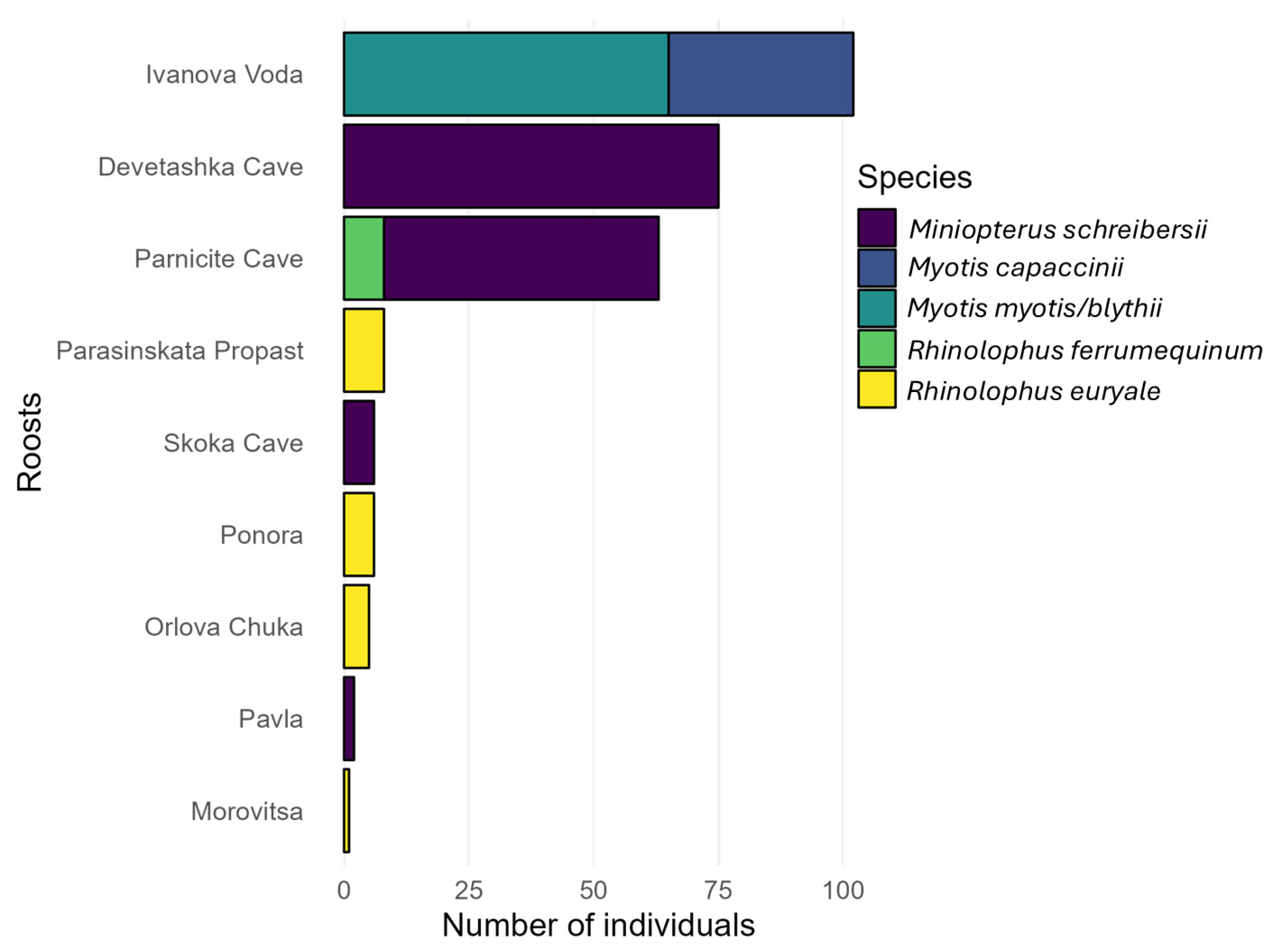

| Site | Species | Year | n |

|---|---|---|---|

| Devetashka Cave | Miniopterus schreibersii | 2012 | 75 |

| Ivanova Voda | Myotis capaccinii | 2012 | 37 |

| Ivanova Voda | Myotis myotis/blythii | 2012 | 65 |

| Parnicite Cave | Miniopterus schreibersii | 2012 | 15 |

| Parnicite Cave | Miniopterus schreibersii | 2022 | 40 |

| Pavla | Miniopterus schreibersii | 2014 | 2 |

| Skoka Cave | Miniopterus schreibersii | 2012 | 6 |

| Parasinskata Propast | Rhinolophus euryale | 2012 | 8 |

| Ponora | Rhinolophus euryale | 2012 | 6 |

| Orlova Chuka | Rhinolophus euryale | 2021–2022 | 5 |

| Morovitsa | Rhinolophus euryale | 2023 | 1 |

| Parnicite Cave | Rhinolophus ferrumequinum | 2012 | 8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Toshkova, N.; Simov, N. Notes on Winter Bat Mortality, Hibernation Preferences, and the Demographic Structure of Deceased Individuals from One of Europe’s Largest Bat Colonies. Conservation 2026, 6, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/conservation6010003

Toshkova N, Simov N. Notes on Winter Bat Mortality, Hibernation Preferences, and the Demographic Structure of Deceased Individuals from One of Europe’s Largest Bat Colonies. Conservation. 2026; 6(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/conservation6010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleToshkova, Nia, and Nikolay Simov. 2026. "Notes on Winter Bat Mortality, Hibernation Preferences, and the Demographic Structure of Deceased Individuals from One of Europe’s Largest Bat Colonies" Conservation 6, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/conservation6010003

APA StyleToshkova, N., & Simov, N. (2026). Notes on Winter Bat Mortality, Hibernation Preferences, and the Demographic Structure of Deceased Individuals from One of Europe’s Largest Bat Colonies. Conservation, 6(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/conservation6010003