Impact of Environmental and Human Factors on the Populations of the Lesser Kestrel (Falco naumanni) at National and Local Scales

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

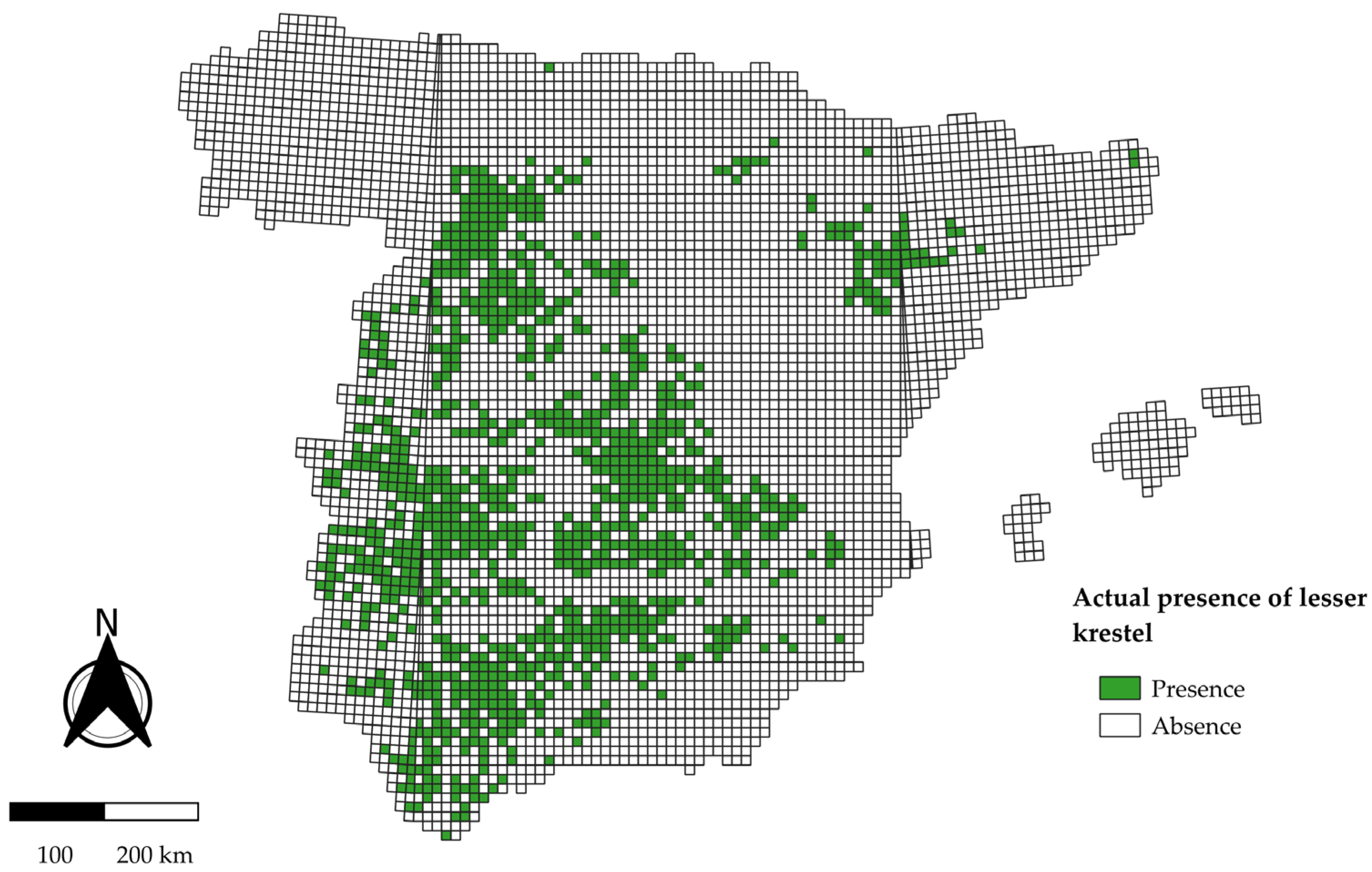

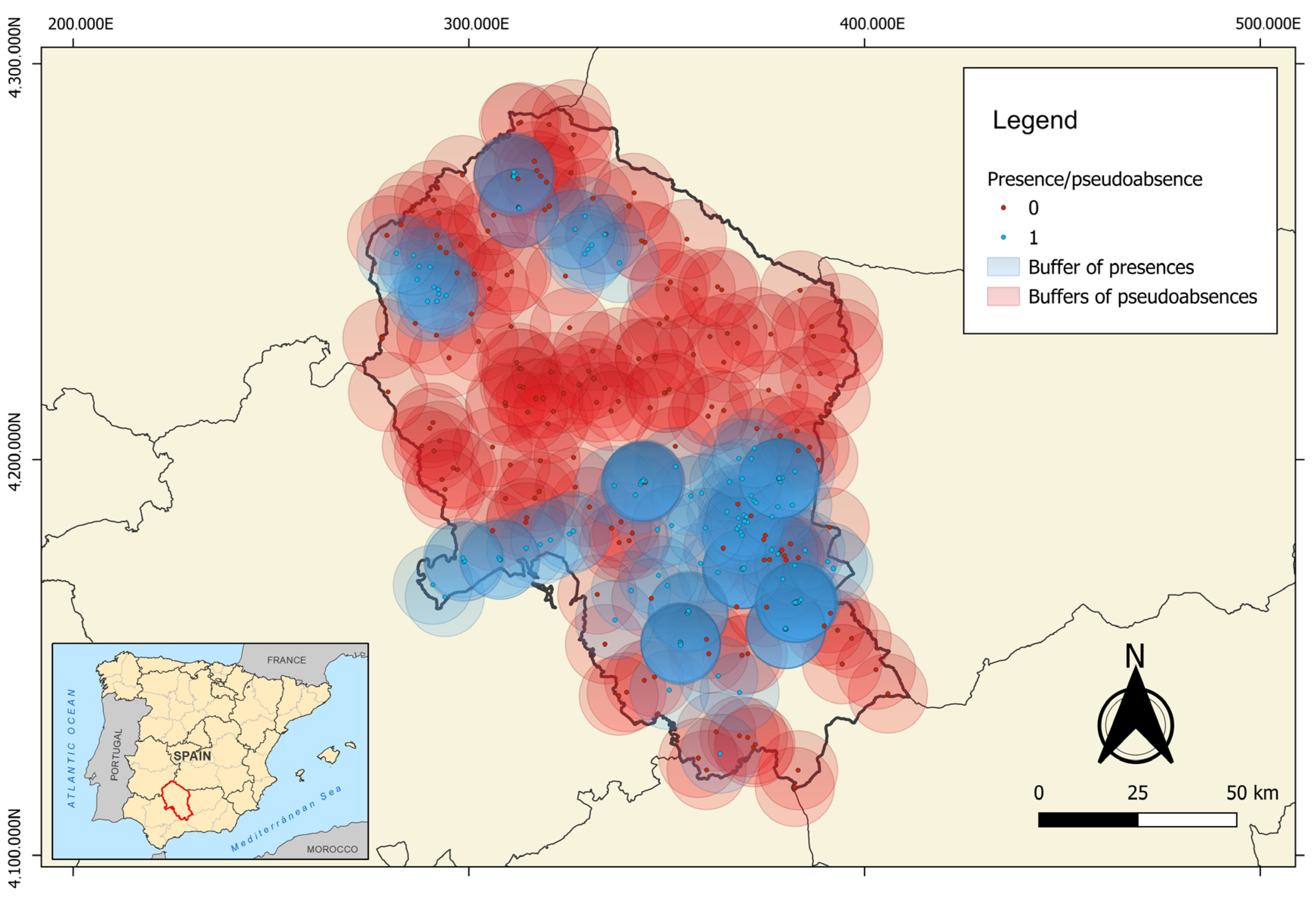

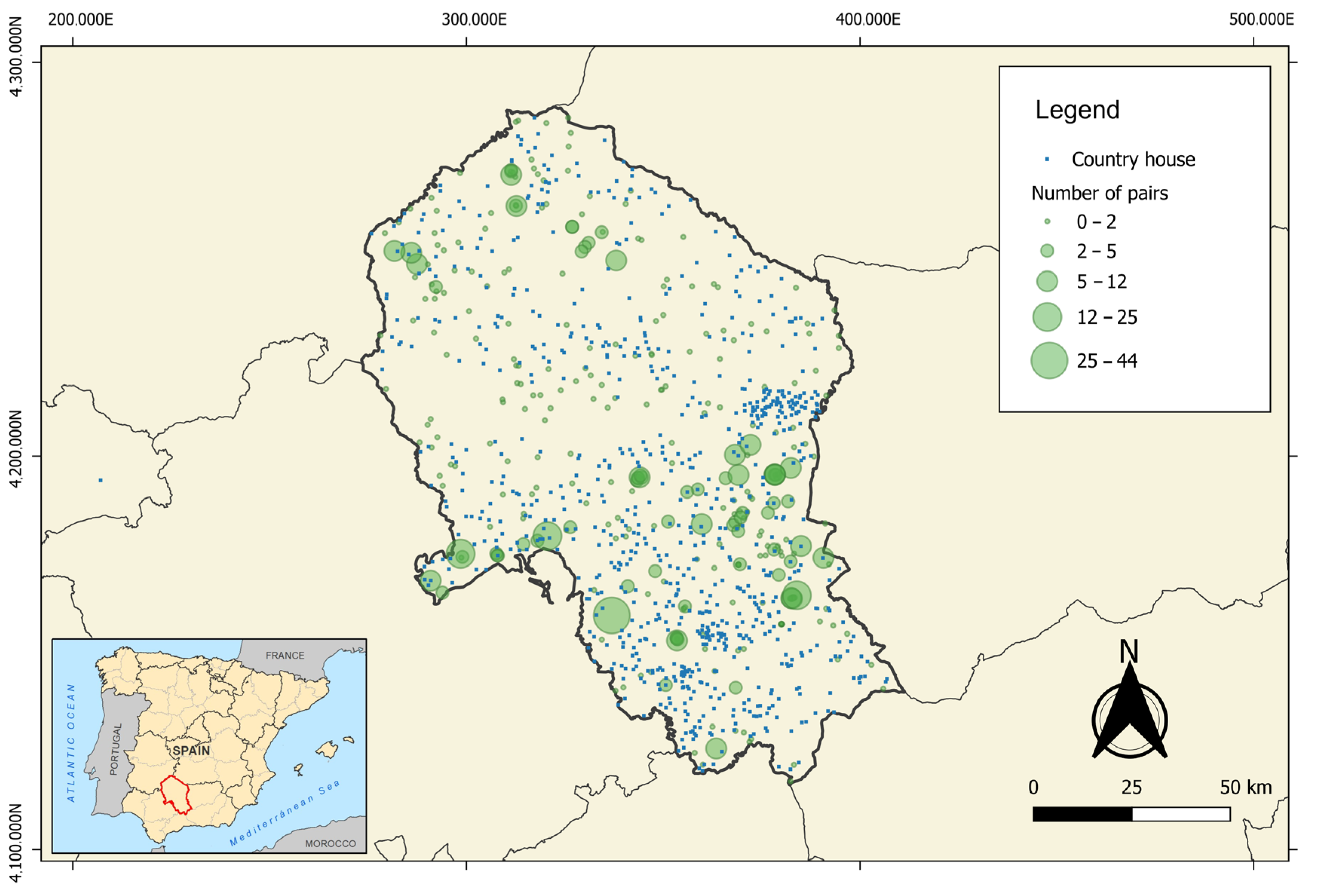

2.2. Biological Data of Lesser Kestrel

2.3. Explanatory Variables

2.3.1. Explanatory Variables of the National-Scale Model

2.3.2. Explanatory Variables of the Local-Scale Model

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

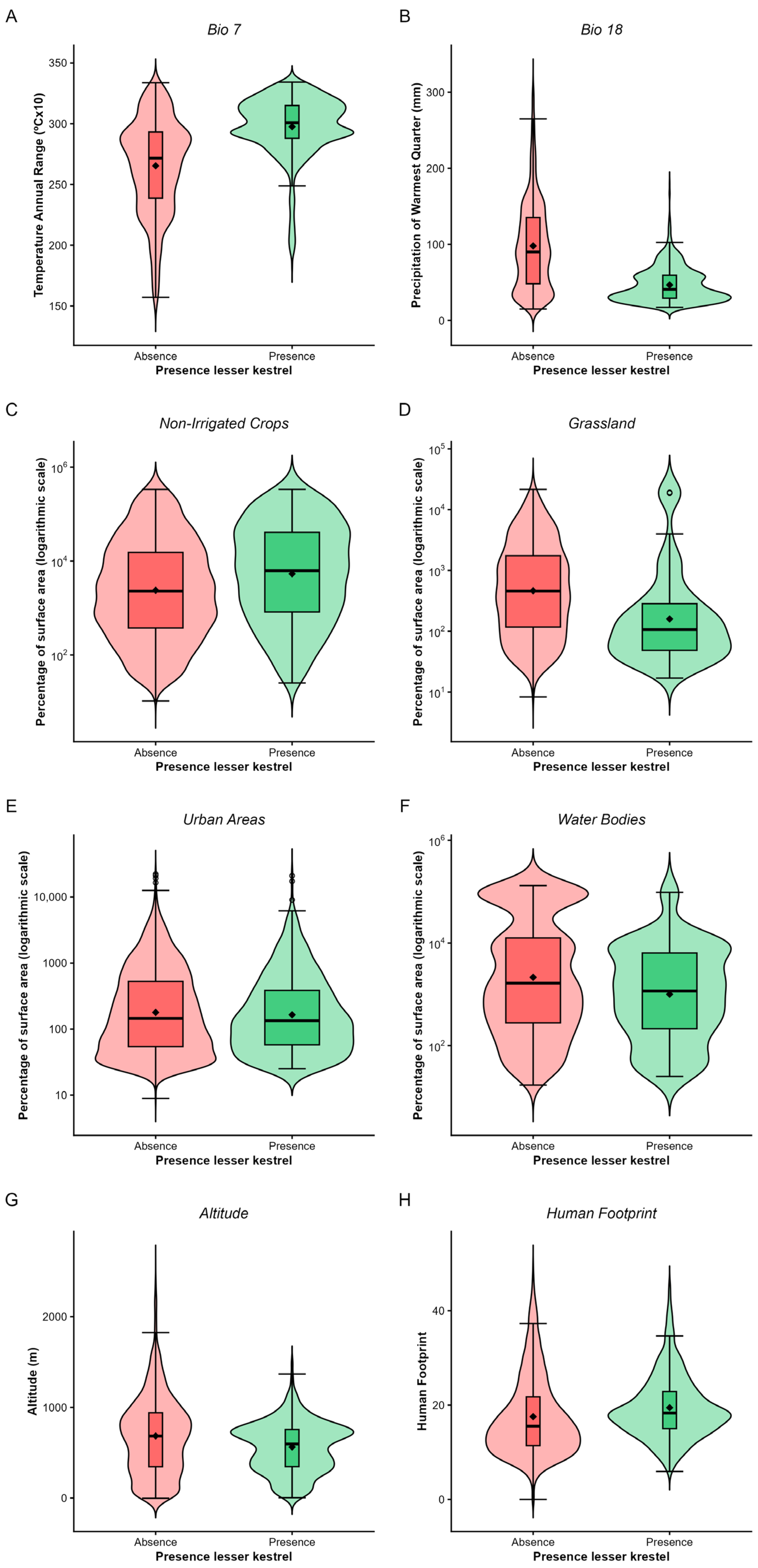

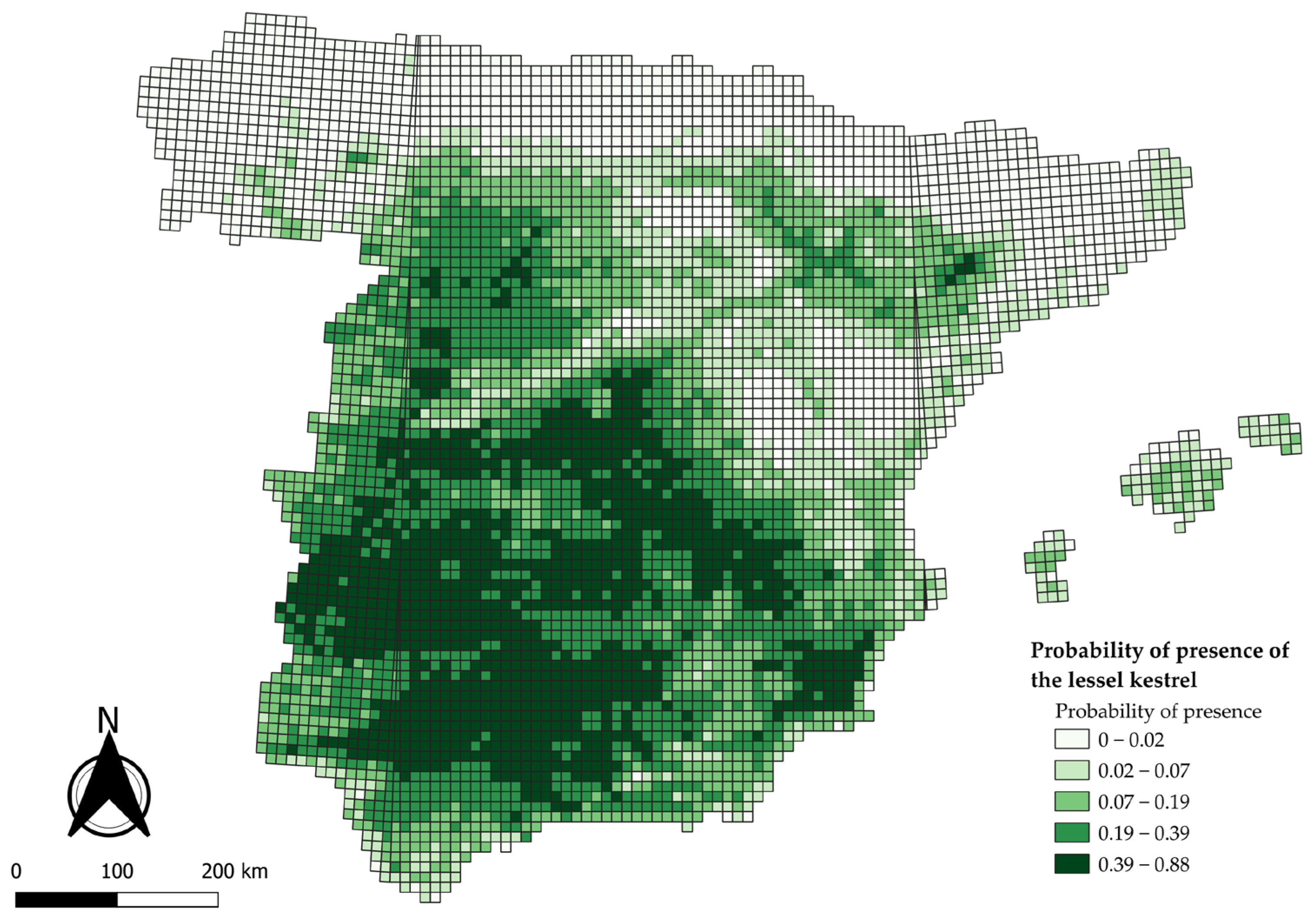

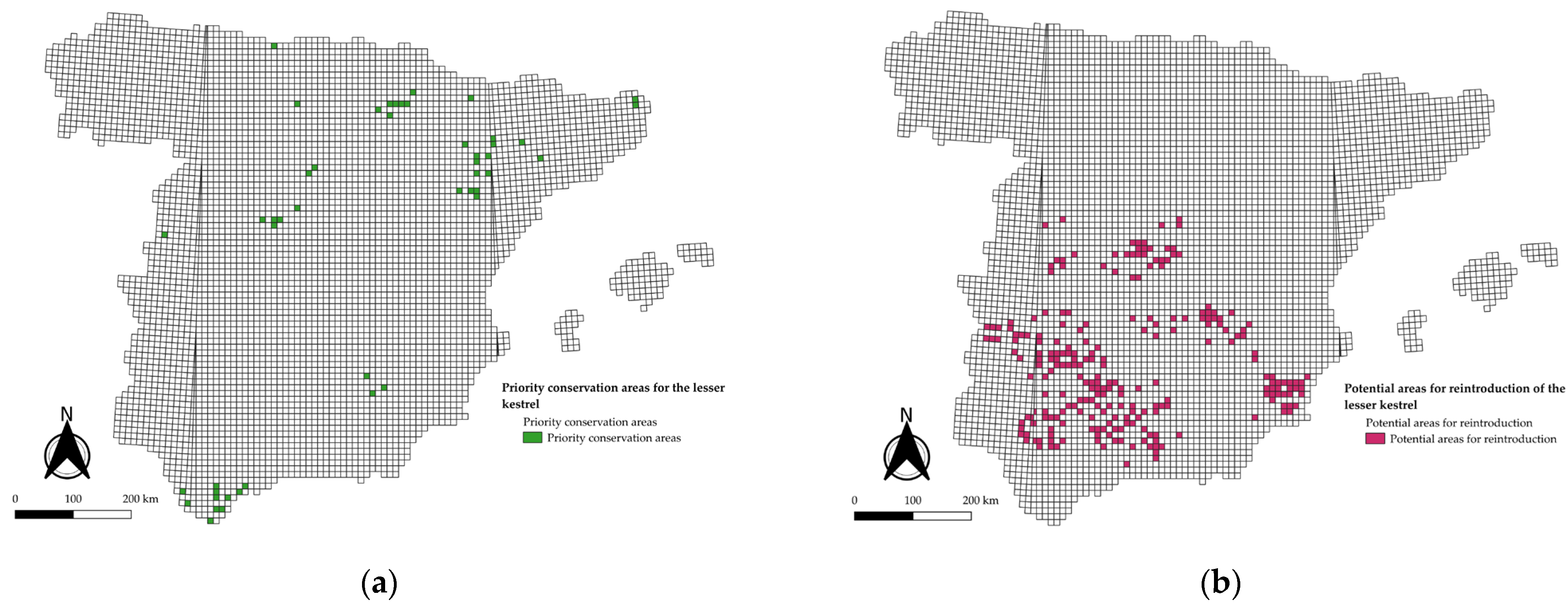

3.1. National-Scale Model

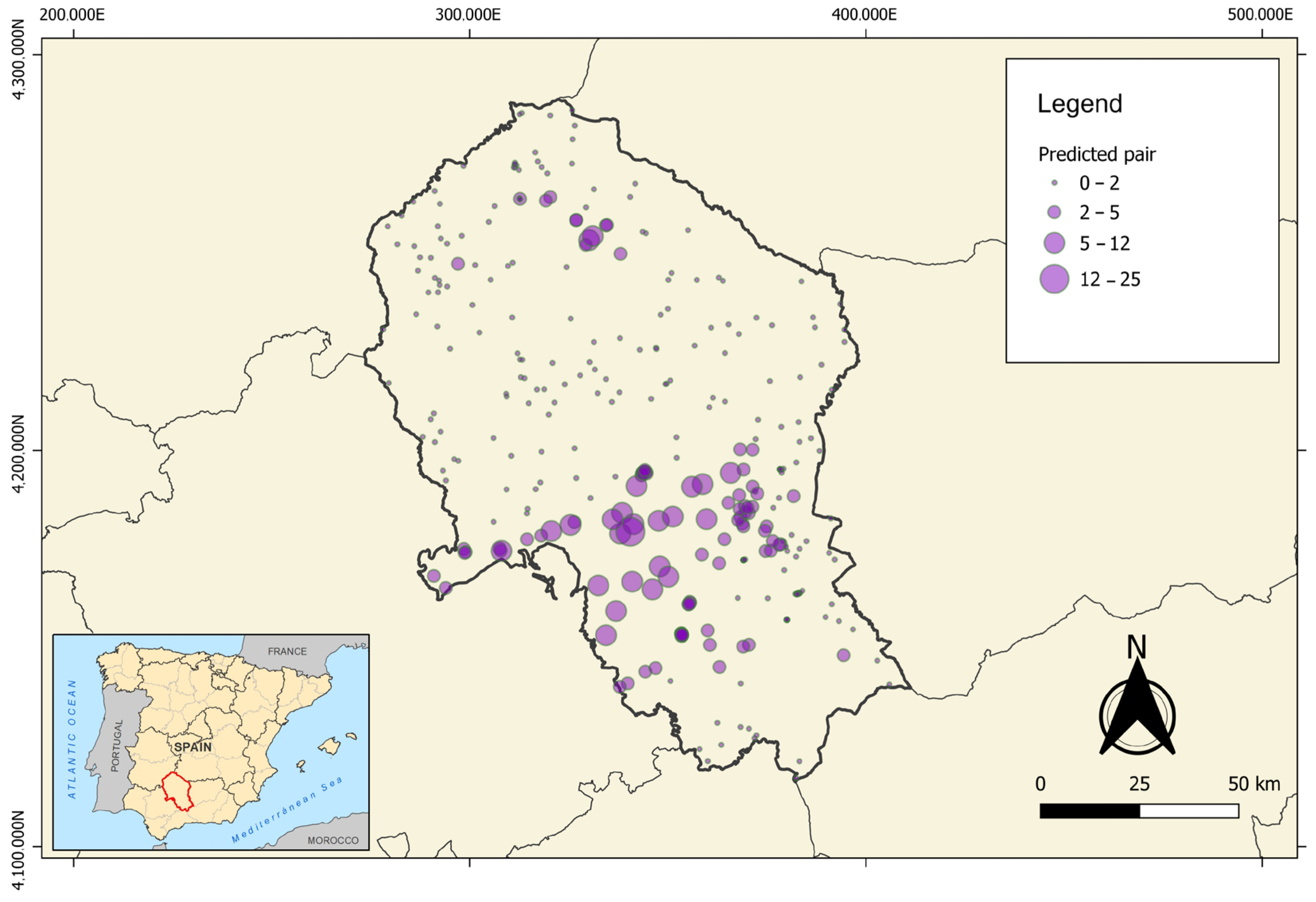

3.2. Local-Scale Model

4. Discussion

4.1. Drivers of National-Scale Patterns

4.2. Ecological Interpretation of Local-Scale Patterns

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GLM | Generalised Linear Model |

| UTM | Universal Transverse Mercator |

| MITECO | Ministry for the Ecological Transition and Demographic Challenge |

| DEM | Digital Elevation Model |

| IGN | Instituto Geográfico Nacional |

| SEDAC | Socioeconomic Data and Applications Center |

| NASA | National Aeronautics and Space Administration |

| CLC | CORINE Land Cover |

| SIOSE | Sistema de Información de Ocupación del Suelo de España |

| CRS | Coordinate Reference Systems |

| GIS | Geographic Information System |

| AIC | Akaike Information Criterion |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

Appendix A. Impact of Environmental and Human Factors on the Populations of the Lesser Kestrel (Falco naumanni) at State and Local Scales

| Reclassification | CORINE | SIOSE |

|---|---|---|

| Urban areas | 111—Continuous urban fabric 112—Discontinuous urban fabric 121—Industrial or commercial units 122—Road and rail networks and associated land 123—Port areas 124—Airports 131—Mineral extraction sites 132—Dump sites 133—Construction sites 141—Green urban areas 142—Sport and leisure facilities | 111—Urban area 112—Suburb 113—Discontinuous urban area 114—Urban green area 121—Agricultural and/or livestock facility 122—Forestry facility 123—Mining extraction 130—Industrial 140—Public service facility 150—Agricultural settlement and orchard 160—Road or rail network 162—Puerto 163—Aeropuerto 171—Supply infrastructure 172—Waste infrastructure 220—Greenhouse |

| Water bodies | 411—Inland marshes 412—Peatbogs 421—Salt marshes 422—Salines 423—Intertidal flats 511—Water courses 512—Water bodies 521—Coastal lagoons 522—Estuaries 523—Sea and ocean | 411—Wet and marshy area 412—Peat bog 413—Salt marsh 414—Salt pan 514—Artificial water body 511—Watercourses 513—Reservoir 515—Sea 516—Glacier and/or perpetual snow |

| Non-irrigated crops | 211—Non-irrigated arable land | 210—herbaceous crop |

| Annual crops | 221—Vineyards 222—Fruit trees and berry plantations 223—Olive groves | 231—Citrus fruit trees 232—Non-citrus fruit trees 233—Vineyards 234—Olive trees 235—Other woody crops 236—Combination of woody crops |

| Irrigated crops | 212—Permanently irrigated land 213—Rice fields | |

| Heterogeneous crop | 241—Annual crops associated with permanent crops 242—Complex cultivation patterns 243—Land principally occupied by agriculture 244—Agro-forestry areas | 250—Crop mix 260—Crop mix with vegetation 340—Vegetation mix |

| Forest | 311—Broad-leaved forest 312—Coniferous forest 313—Mixed forest | 311—Deciduous forest 313—Mixed forest 312—Coniferous forest |

| Scrubland | 321—Natural grassland 322—Moors and heathland 323—Sclerophyllous vegetation 324—Transitional woodland shrub | 330—Scrubland |

| Grassland | 231—Pastures | 320—Grassland or Herbaceous vegetation 240—Pasture |

| Other | 331—Beaches, dunes, and sand plains 332—Bare rock 333—Sparsely vegetated areas 334—Burnt areas 335—Glaciers and perpetual snow | 351—Beach, dune or sandy area 352—Rocky area 353—Temporarily deforested due to fires 354—Bare soil |

References

- Farjalla, V.F.; Coutinho, R.; Gómez, L.; Navarrete, S.A.; Aliny, P.F.; Pires, M.L.; Soares, A.T.; Vale, M.M. Loss of biodiversity: Causas y consecuencias para la humanidad. In Cambio Global. Una Mirada Desde Iberoamérica; ACCI: Madrid, Spain, 2018; pp. 89–110. Available online: https://digital.csic.es/handle/10261/209085 (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Díaz, S.; Settele, J.; Brondízio, E.S.; Ngo, H.T.; Agard, J.; Arneth, A.; Balvanera, P.; Brauman, K.A.; Butchart, S.H.M.; Chan, K.M.A.; et al. Pervasive human-driven decline of life on Earth points to the need for transformative change. Science 2019, 366, eaax3100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dirzo, R.; Young, H.S.; Galetti, M.; Ceballos, G.; Isaac, N.J.B.; Collen, B. Defaunation in the Anthropocene. Science 2014, 345, 401–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, G.; Suárez, L. La Biodiversidad, en Estado de Emergencia. 15 Peticiones para Salvar la Naturaleza en ESPAÑA; WWF España: Madrid, Spain, 2020; Available online: https://www.wwf.es/?54680/Informe-La-biodiversidad-en-estado-de-emergencia-Quince-medidas-para-salvar-la-naturaleza-en-Espana (accessed on 21 June 2025).

- McClure, C.J.W.; Westrip, J.R.S.; Johnson, J.A.; Schulwitz, S.E.; Virani, M.Z.; Davies, R.; Symes, A.; Wheatley, H.; Thorstrom, R.; Amar, A.; et al. State of the world’s raptors: Distributions, threats, and conservation recommendations. Biol. Conserv. 2018, 227, 390–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, S.M.; Settele, J.; Brondízio, E.; Ngo, H.; Guèze, M.; Agard, J.; Arneth, A.; Balvanera, P.; Brauman, K.; Butchart, S.; et al. The Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services: Summary for Policy Makers; Intergovernmental Science Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services: Bonn, Germany, 2019. Available online: https://ri.conicet.gov.ar/handle/11336/116171 (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Sergio, F.; Newton, I.; Marchesi, L. Top predators and biodiversity: Much debate, few data. J. Appl. Ecol. 2008, 45, 992–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donázar, J.A.; Cortés Avizanda, A.; Fargallo, J.A.; Margalida, A.; Moleón, M.; Morales Reyes, Z.; Moreno Opo, R.; Pérez García, J.M.; Sánchez Zapata, J.A.; Zuberogoitia, I.; et al. Roles of raptors in a changing world: From flagships to providers of key ecosystem services. Ardeola 2016, 63, 181–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tella, J.L. Condicionantes Ecológicos, Costes Y Beneficios Asociados a la Colonialidad en el Cernícalo Primilla. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Di Maggio, R.; Campobello, D.; Sara, M. Nest aggregation and reproductive synchrony promote lesser kestrel Falco naumanni seasonal fitness. J. Ornithol. 2013, 154, 901–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustamante, J.; Molina, B.; Del Moral, J.C. El Cernícalo Primilla en España, Población Reproductora en 2016–18 y Método de Censo; SEO/BirdLife: Madrid, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bustamante, J.; Molina, B.; Del Moral, J.C. Cernícalo primilla, Falco naumanni. In El Libro Rojo de las Aves de España; Sociedad Española de Ornitología: Madrid, Spain, 2021; pp. 600–606. [Google Scholar]

- Bustamante, J. Predictive models for lesser kestrel Falco naumanni distribution, abundance and extinction in southern Spain. Biol. Conserv. 1997, 80, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arenas, R.; Carrasco, M.; Leiva, A. Aves Esteparias; Diputación de Córdoba, Delegación de Infraestructuras, Sostenibilidad y Agricultura: Córdoba, Spain, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Donázar, J.A.; Negro, J.J.; Hiraldo, F. Foraging habitat selection, land-use changes and population decline in the Lesser Kestrel Falco naumanni. J. Appl. Ecol. 1993, 30, 515–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparicio, J.M.; Muñoz, A.; Cordero, P.J.; Bonal, R. Causes of the recent decline of a Lesser Kestrel (Falco naumanni) population under an enhanced conservation scenario. Ibis 2023, 165, 388–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, B.M. Patrones de Cambio en Los Usos del Suelo Durante las Tres Últimas Décadas en la Península Ibérica. Master’s Thesis, Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha, Ciudad Real, Spain, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Tella, J.L.; Forero, M.G.; Hiraldo, F.; Donázar, J.A. Conflicts between Lesser Kestrel Conservation and European Agricultural Policies as Identified by Habitat Use Analyses. Conserv. Biol. 1998, 12, 593–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negro, J.J.; Bustamante, J.; Melguizo, C.; Ruiz, J.L.; Grande, J.M. Nocturnal activity of lesser kestrels under artificial lighting conditions in Seville, Spain. Raptor Res. 2000, 34, 327–329. [Google Scholar]

- Garrido, J.R.; de las Heras, M. El cernícalo primilla en Andalucía. In El Cernícalo Primilla en España, Población Reproductora en 2016–18 y Método de Censo; Bustamante, J., Molina, B., Del Moral, J.C., Eds.; SEO/BirdLife: Madrid, Spain, 2020; pp. 50–61. [Google Scholar]

- Forero, M.G.; Tella, J.L.; Donázar, J.A.; Hiraldo, F. Can interspecific competition and nest site availability explain the decrease of lesser kestrel Falco naumanni populations? Biol. Conserv. 1996, 78, 289–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciscar, J.C.; García León, D. Impactos y Riesgos del Cambio Climático en España: Una Breve Panorámica; FUNCAS: Madrid, Spain, 2022; Available online: https://www.funcas.es/articulos/impactos-y-riesgos-del-cambio-climatico-en-espana-una-breve-panoramica/ (accessed on 22 June 2025).

- Benavídez Silva, J. Uso del suelo, cambio climático y biodiversidad. Investig. Reg.—J. Reg. Res. 2024, 58, 135–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayuntamiento de Córdoba. Plan Municipal Contra el Cambio Climático de Córdoba; Delegación de Medio Ambiente y Transición Energética: Córdoba, Spain, 2022; Available online: https://www.cordoba.es/sites/default/files/PDF/Servicios/medio-ambiente/plan-municipal-contra-el-cambio-climatico-de-cordoba/03.INFORME_ERYV_V4.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Junta de Andalucía, Consejería de Medio Ambiente. Tipología de Suelos en Andalucía; Junta de Andalucía: Sevilla, Spain, 2004; pp. 27–36. Available online: https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/medioambiente/web/Bloques_Tematicos/Estado_Y_Calidad_De_Los_Recursos_Naturales/Suelo/Criterios_pdf/Tipologia.pdf (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Ministerio para la Transición Ecológica y el Reto Demográfico. Inventario Español de Especies Terrestres (IEET); Inventario Nacional de Biodiversidad: Madrid, Spain, 2011; Available online: https://www.miteco.gob.es/es/biodiversidad/temas/inventarios-nacionales/inventario-especies-terrestres/inventario-nacional-de-biodiversidad/bdn-ieet-default.html (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Fick, S.E.; Hijmans, R.J. WorldClim 2: New 1 km spatial resolution climate surfaces for global land areas. Int. J. Climatol. 2017, 37, 4302–4315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortego, J.; Aparicio, J.M.; Munoz, A.; Bonal, R. Malathion applied at standard rates reduces fledgling condition and adult male survival in a wild lesser kestrel population. Anim. Conserv. 2007, 10, 312–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Geográfico Nacional. Modelo Digital del Terreno (MDT): Altitud [Geospatial Layer]; Centro Nacional de Información Geográfica: Madrid, Spain, 2014; Available online: https://centrodedescargas.cnig.es/CentroDescargas/home (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Wildlife Conservation Society–WCS; Center for International Earth Science Information Network–CIESIN (Columbia University). Last of the Wild Project, Version 3 (LWP-3): Human Footprint 2009, 2018 Release (Version 1.00) [Geospatial Dataset]; NASA Socioeconomic Data and Applications Center (SEDAC): Palisades, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Environment Agency; Copernicus Land Monitoring Service. CORINE Land Cover 2018 (CLC2018), Europe, 6 Yearly (V2020_20u1) [Vector Geospatial Dataset]. 2020. Available online: https://sdi.eea.europa.eu/catalogue/copernicus/api/records/71c95a07-e296-44fc-b22b-415f42acfdf0?language=all (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- Catry, I.; Franco, A.M.A.; Sutherland, W.J. Landscape and weather determinants of prey availability: Implications for the Lesser Kestrel Falco naumanni. Ibis 2012, 154, 529–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Estrella, R.; Donázar, J.A.; Hiraldo, F. Influence of environmental factors and human activity on the distribution of breeding colonies of the Lesser Kestrel Falco naumanni in Spain. Biol. Conserv. 1998, 84, 189–195. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Granados, C. Diet of adult Lesser Kestrels Falco naumanni during the breeding season in central Spain. Ardeola 2010, 57, 443–448. [Google Scholar]

- Junta de Andalucía, Consejería de Obras Públicas y Transportes; Dirección General de Arquitectura y Vivienda. Cortijos, Haciendas y Lagares: Arquitectura de las Grandes Explotaciones Agrarias de Andalucía. Provincia de Córdoba; Volumes 1–2, Junta de Andalucía: Sevilla, Spain, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Consejería de Sostenibilidad, Medio Ambiente y Economía Azul, Junta de Andalucía. Mapa de Usos y Coberturas Vegetales del Suelo de Andalucía (2007), Scale 1:25,000 [WMS/WFS Service]; REDIAM—Red de Información Ambiental de Andalucía: Sevilla, Spain, 2010; Available online: http://portalrediam.cica.es/geonetwork/srv/api/records/21a12118-420f-495a-9f52-35179ed40a5c/formatters/xml?approved=true (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing, version 4.4.1; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2025; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Zuur, A.F.; Ieno, E.N.; Walker, N.J.; Saveliev, A.A.; Smith, G.M. GLM and GAM for count data. In Mixed Effects Models and Extensions in Ecology with R; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 209–243. Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-0-387-87458-6_7 (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Burnham, K.P.; Anderson, D.R. Model Selection and Multimodel Inference: A Practical Information-Theoretic Approach, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bontzorlos, V.A.; Xirouchakis, S.M. Foraging habitat selection of the Lesser Kestrel Falco naumanni in a lowland area of Central Greece. Ornithol. Sci. 2021, 20, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, C.; Bustamante, J. Patterns of Orthoptera abundance and lesser kestrel conservation in arable landscapes. Biodivers. Conserv. 2008, 17, 1753–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, S.; Tigae, C.; Dobrițescu, A.; Ștefănescu, M.D. Exploring the climatic niche evolution of the genus Falco (Aves: Falconidae) in Europe. Biology 2024, 13, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catry, I.; Alcázar, R.; Henriques, I. The role of nest-site provisioning in increasing lesser kestrel Falco naumanni numbers in Castro Verde Special Protection Area, southern Portugal. Conserv. Evid. 2007, 4, 54–57. Available online: https://www.conservationevidence.com/individual-study/2260 (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Negro, J.J. Adaptations of lesser kestrels to agricultural habitat in southern Spain. J. Raptor Res. 1997, 31, 72–77. [Google Scholar]

- Sarà, M.; Campobello, D.; Zanca, L.; Massa, B. Food for flight: Pre-migratory dynamics of the Lesser Kestrel Falco naumanni. Bird Study 2014, 61, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catry, I.; Amano, T.; Franco, A.M.A.; Sutherland, W.J.; Evans, K.L. Estimating potential distribution of European Rollers (Coracias garrulus) under future climatic scenarios and assessing extinction risks. Biol. Conserv. 2012, 145, 80–89. [Google Scholar]

- Franco, A.M.A.; Sutherland, W.J. Modelling the foraging habitat selection of Lesser Kestrels: Conservation implications of European Agricultural Policies. Biol. Conserv. 2004, 120, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assandri, G.; Kamp, J.; Bontzorlos, V.A.; Buechley, E.R.; Catry, I.; Cecere, J.G.; Franco, A.M.A.; Rodríguez, C.; Santangeli, A. Context-dependent habitat selection in Lesser Kestrels Falco naumanni revealed by GPS tracking. IBIS 2022, 164, 1081–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobek, M.; Bělka, T.; Peške, L.; Šálek, M.; Bělka, T. Effect of nest-site microclimatic conditions on nesting success and nestling development in a cavity-nesting raptor. Bird Study 2018, 65, 552–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Factor | Variable | Spatial Resolution |

|---|---|---|

| Environmental | Bio 1 1: Annual Mean Temperature 2 | 1 Km |

| Bio 2 1: Mean Diurnal Range 2 | ||

| Bio 3 1: Isothermality 2 | ||

| Bio 4 1: Temperature Seasonality 2 | ||

| Bio 5 1: Max Temperature of Warmest Month 2 | ||

| Bio 6 1: Min Temperature of Coldest Month 2 | ||

| Bio 7: Temperature Annual Range 2 | ||

| Bio 8: Mean Temperature of Wettest Quarter 2 | ||

| Bio 9 1: Mean Temperature of driest Quarter 2 | ||

| Bio 10 1: Mean Temperature of Warmest Quarter 2 | ||

| Bio 11 1: Mean Temperature of Coldest Quarter 2 | ||

| Bio 12 1: Annual Precipitation 2 | ||

| Bio 13 1: Precipitation of Wettest Month 2 | ||

| Bio 14 1: Precipitation of Driest Month 2 | ||

| Bio 15 1: Precipitation Seosanility 2 | ||

| Bio 16 1: Precipitation of Wettest Quarter 2 | ||

| Bio 17 1: Precipitation of Driest Quarter 2 | ||

| Bio 18: Precipitation of Warmest Quarter 2 | ||

| Bio 19 1: Precipitation of Coldest Quarter 2 | ||

| Altitude 3 | 20 m | |

| Anthropogenic | Human footprint 4 | 1 Km |

| Land Cover | Heterogeneous crops 5 | 500 m |

| Annual crops 5 | ||

| Forest 1,5 | ||

| Scrubland 5 | ||

| Grassland 5 | ||

| Irrigated crops 1,5 | ||

| Non-irrigated crops 5 | ||

| Urban areas 5 | ||

| Water bodies 5 Others 5 | ||

| Biological | Presence of lesser kestrel 6 | 10 Km |

| Presence of common kestrel 6 | 10 Km | |

| N° of prey species 6 | 10 Km |

| Factor | Variable | Spatial Resolution |

|---|---|---|

| Anthropogenic | Distance to the nearest country house 1 | |

| Land Cover | Heterogeneous crops 2 | 50 m |

| Annual crops 2 | ||

| Forest 2 | ||

| Scrubland 2 | ||

| Grassland 2 | ||

| Non-irrigated crops 2 | ||

| Urban areas 2 | ||

| Water bodies 2 | ||

| Other 2 | ||

| Biological | Lesser kestrel population nuclei 3 | 10 km (buffers) |

| Pseudo-absences | ||

| Diversity metrics | Shannon’s Diversity Index | 50 m |

| Simpson’s Diversity Index | ||

| Mean Patch Area | ||

| Fragmentation and structure metrics | Number of Patches | |

| Patch Density | ||

| Edge Density | ||

| Landscape Cohesion Index |

| Estimate | Standard Error | z-Value | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −7.39 | 6.8 × 10−1 | −10.82 | <0.0001 |

| Presence of Common Kestrel | 6.1 × 10−1 | 1.5 × 10−1 | 4.16 | <0.0001 |

| Bio 7 | 2 × 10−2 | 2.1 × 10−3 | 10.79 | <0.0001 |

| Bio 18 | −2 × 10−2 | 2.0 × 10−3 | −11.51 | <0.0001 |

| Heterogeneous Crops | 3.0 × 10−6 | 1.9 × 10−6 | 1.58 | >0.05 |

| Annual Crops | 5.3 × 10−6 | 3.6 × 10−6 | 1.48 | >0.05 |

| Grassland | 8.1 × 10−5 | 3.2 × 10−5 | 2.54 | <0.05 |

| Non-irrigated Crops | 2.8 × 10−6 | 6.4 × 10−7 | 4.32 | <0.0001 |

| Urban Areas | −1.4 × 10−4 | 4.8 × 10−5 | −2.83 | <0.01 |

| Water Bodies | −1.7 × 10−5 | 3.6 × 10−6 | −4.80 | <0.0001 |

| Altitude | −8.3 × 10−4 | 2.0 × 10−4 | −4.21 | <0.0001 |

| Human Footprint | 6 × 10−2 | 1 × 10−2 | 8.49 | <0.0001 |

| N° of Prey Species | 1.6 × 10−1 | 3 × 10−2 | 4.73 | <0.0001 |

| Bio 8 | −3.0 × 10−3 | 1.8 × 10−3 | −1.67 | >0.05 |

| Scrubland | −6.2 × 10−6 | 4.0 × 10−6 | −1.54 | >0.05 |

| Estimate | Standard Error | z-Value | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 1.268 | 8.167 × 10−1 | 1.552 | >0.05 |

| Urban areas | 2.248 × 10−4 | 8.491 × 10−5 | 2.647 | <0.01 |

| Water bodies | −9.562 × 10−4 | 4.395 × 10−4 | −2.176 | <0.05 |

| Non-irrigated Crops | 7.031 × 10−5 | 1.775 × 10−5 | 3.960 | <0.0001 |

| Woodland | −2.493 × 10−4 | 7.084 × 10−5 | −3.519 | <0.01 |

| Grassland | 2.561 × 10−4 | 1.498 × 10−4 | 1.709 | >0.05 |

| Open areas | −1.529 × 10−3 | 4.569 × 10−4 | −3.347 | <0.01 |

| Mean Patch Area | −4.819 × 10−2 | 2.071 × 10−2 | −2.326 | <0.05 |

| Distance country house | 7.745 × 10−11 | 4.850 × 10−11 | 1.597 | >0.05 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Villacañas, M.; Carpio, A.J.; Acosta-Muñoz, C. Impact of Environmental and Human Factors on the Populations of the Lesser Kestrel (Falco naumanni) at National and Local Scales. Conservation 2026, 6, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/conservation6010002

Villacañas M, Carpio AJ, Acosta-Muñoz C. Impact of Environmental and Human Factors on the Populations of the Lesser Kestrel (Falco naumanni) at National and Local Scales. Conservation. 2026; 6(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/conservation6010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleVillacañas, María, Antonio J. Carpio, and Cristina Acosta-Muñoz. 2026. "Impact of Environmental and Human Factors on the Populations of the Lesser Kestrel (Falco naumanni) at National and Local Scales" Conservation 6, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/conservation6010002

APA StyleVillacañas, M., Carpio, A. J., & Acosta-Muñoz, C. (2026). Impact of Environmental and Human Factors on the Populations of the Lesser Kestrel (Falco naumanni) at National and Local Scales. Conservation, 6(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/conservation6010002