Human–Wildlife Coexistence in Japan: Adapting Social–Ecological Systems for Culturally Informed Management

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Foundation: The SES Framework and Its Limitations in Japan

2.1. Introduction: The Need for an Integrated Framework

2.2. The Social–Ecological Systems (SES) Framework: Rationale and Core Components

2.3. Diagnosing the Gaps: Limitations of the Standard SES Framework in the Japanese HWC Context

2.3.1. Inadequate Capture of Cultural Specificity, Relational Values, and Traditional Ecological Knowledge

2.3.2. Overlooking Profound Demographic Change and Community Dynamics

2.3.3. Insufficient Attention to Institutional Specificity: The Role of the Ryōyūkai

2.3.4. Lack of Explicit Focus on Power Dynamics and Conflict

2.3.5. Potential Overemphasis on Material Outcomes

2.4. The Imperative of Contextual Adaptation and This Paper’s Contribution

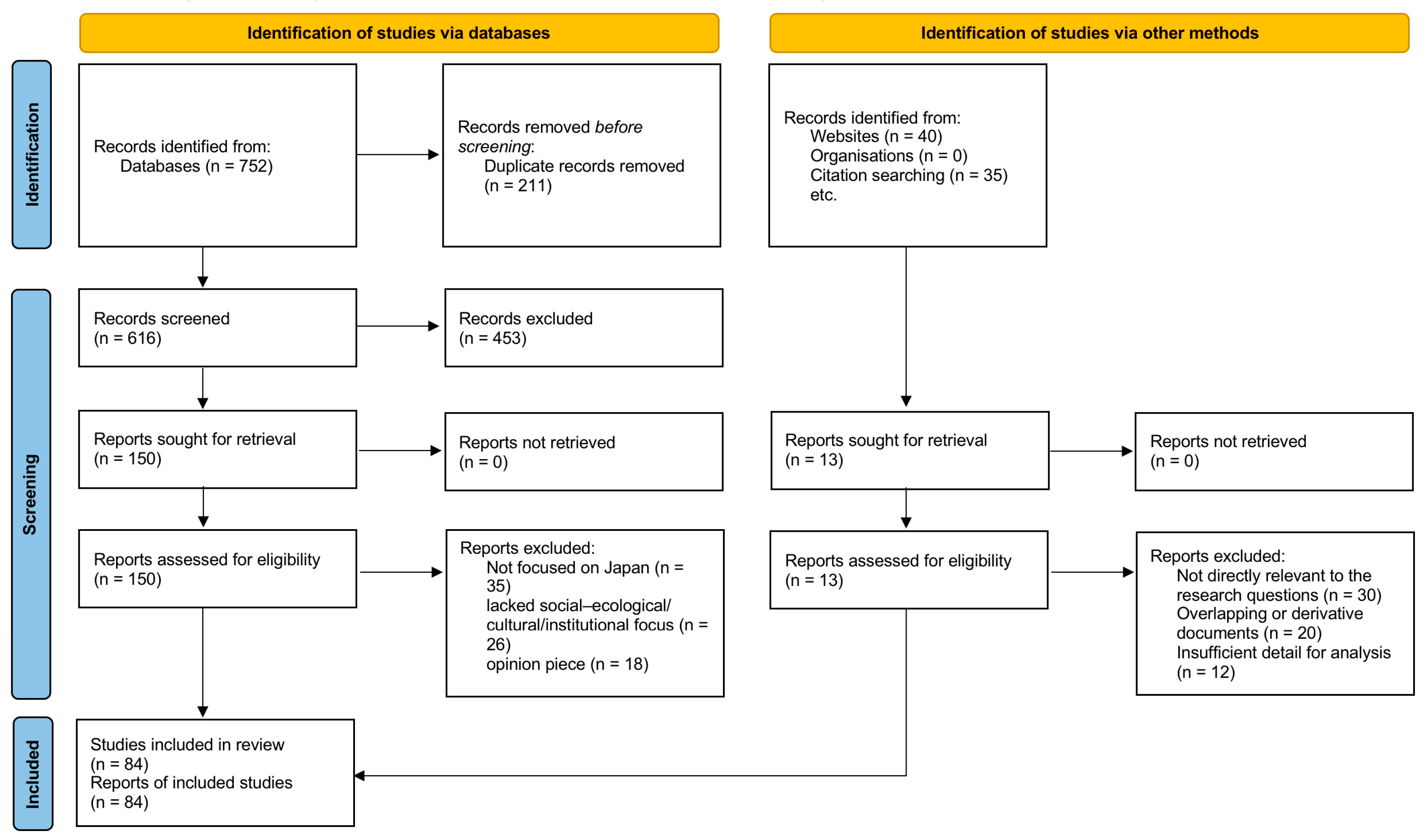

3. Methodology: A Scoping Review Approach to Framework Adaptation

3.1. Stage 1: Identifying the Research Questions and the Relevant Literature

3.2. Stage 2: Selecting Relevant Studies

3.3. Stage 3: Charting the Data

3.4. Stage 4: Collating, Synthesizing, and Developing the Adapted Framework

3.5. Stage 5: The Methodology Structure of the Paper

4. Japanese Context: Socio-Ecological Landscape of HWC

4.1. Historical Roots: Shifting Landscapes and Human-Nature Relations

4.2. Cultural Dimensions: Values, Perceptions, and Ambivalence

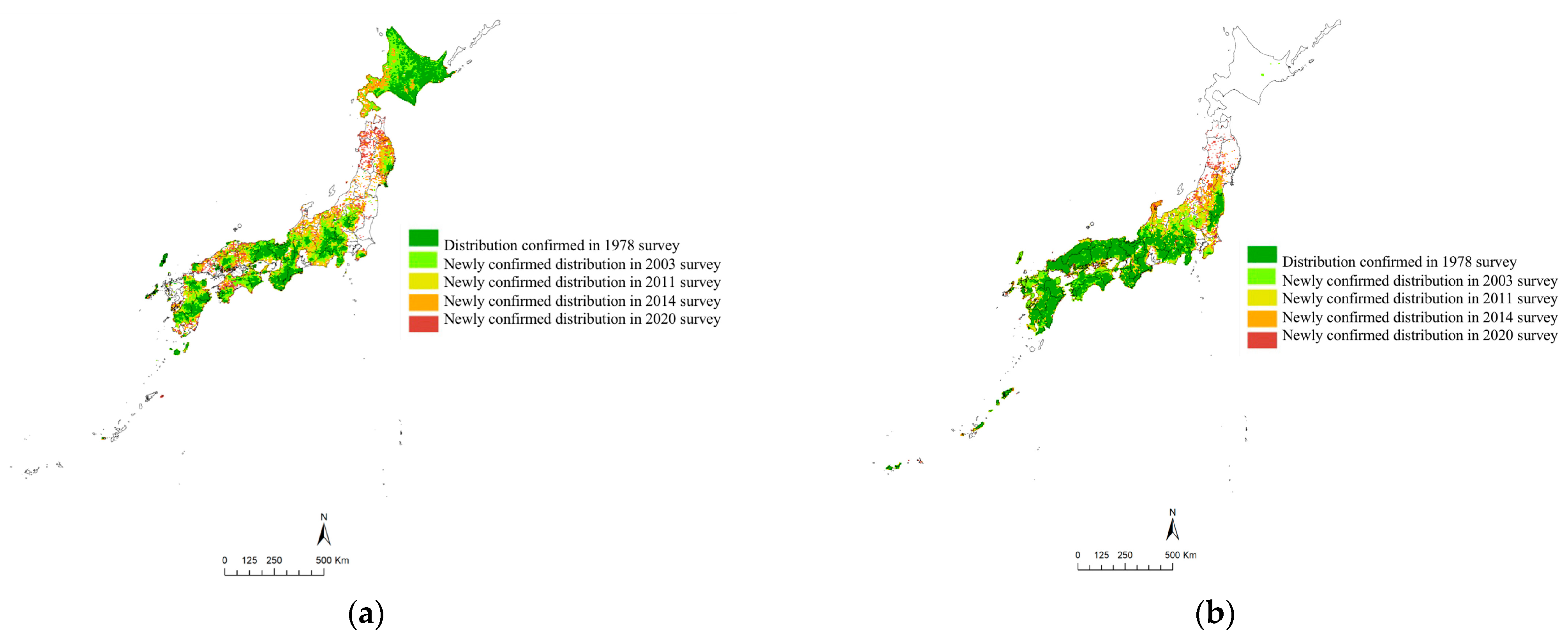

4.3. Manifestations of HWC: Damage, Impacts, and Bottlenecks

4.4. Stakeholder Deep Dive: Actors, Institutions, and Power Dynamics

4.4.1. Hunters and the Ryōyūkai: A System Under Strain

4.4.2. Local Communities: Facing Impacts with Diminished Capacity

4.4.3. Government Actors: Multi-Level Governance and Coordination Challenges

| Core Sub-System (Ostrom, 2009 [22]) | Key Variables (Standard SES—Examples) | Proposed Adaptations/Refinements for Japanese HWC Context | Rationale/Relevance & Link to Limitations (Problem -> Solution) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social, Economic & Political Settings (S) | S1 Econ. Development, S2 Demo. Trends, S3 Political Stability | S-DEM: Fundamental Demographic Trends (kaso, kōreika) S-CUL: Overarching Cultural Context & Narratives (kyōsei, Shinto-Buddhism) S-HIST: Historical Land-Use Legacies (afforestation) | Problem: Standard SES often treats deep demographic and cultural trends as external “settings”, failing to capture their role as core system drivers. Solution: These variables internalize kaso, kōreika, and historical land-use legacies as fundamental endogenous forces, providing the foundational context for analyzing system-wide dynamics. |

| Resource System (RS) | RS3 System Boundaries, RS5 Productivity, RS8 Habitat Heterogeneity | RS-LC: Landscape Transformation Dynamics (satoyama status) RS-CSL: Cultural Significance of Landscape (satoyama heritage) | Problem: A standard approach can analyze ecological change without deeply connecting it to the underlying socio-economic roots. Solution: These variables explicitly link landscape-level changes that drive HWC (e.g., satoyama degradation) directly to their historical (S-HIST) and demographic (S-DEM) drivers. |

| Resource Units (RU) | RU1 Mobility, RU2 Economic Value, RU3 Size | RU-CSV: Species-Specific Cultural Significance & Perception (ambivalent views) RU-ECO: Ecological Role vs. Perceived Nuisance | Problem: Standard variables struggle to capture the non-material, often ambivalent, cultural meanings of wildlife that are central to social conflict. Solution: These variables are designed to diagnose the complex, often contradictory cultural views of key species, explaining why technically sound management can be socially contested. |

| Governance System (GS) | GS2 Govt. Type, GS6 Collective-Choice Rules, GS8 Monitoring | GS-IH: Institutional Hybridity & Stress (Ryōyūkai Focus) GS-MC: Multi-Level Coordination Dynamics GS-LEG: Legitimacy & Social Acceptance GS-POW: Authority Structures in Rule-Making | Problem: Generic governance variables can miss the fragility of unique local institutions and often overlook the influence of power. Solution: These variables provide specific tools to diagnose the vulnerability of unique institutions like the Ryōyūkai (GS-IH) and make the analysis of legitimacy (GS-LEG) and power (GS-POW) a core, explicit part of governance assessment. |

| Actors (A) | A1 Number, A5 Leadership, A6 Norms & Social Capital, A7 Knowledge (TEK) | A-DC: Demographic Constraints & Capacity A-CVR: Cultural Values & Relationality A-MOT: Shifting Motivations A-POW: Differential Influence & Authority A-PSY: Risk Perception & Psychological Factors | Problem: Standard actor analysis often lacks sufficient granularity to explain behavior driven by deep demographic, cultural, and psychological forces. Solution: These variables provide a richer, more realistic view by directly integrating the demographic crisis (A-DC), cultural values (A-CVR), and psychological factors (A-PSY) into the analysis of actor capacity and motivation. |

| Interactions (I) | Harvesting, Monitoring, Conflict, Lobbying, Self-organization | I-POW: Influence of Power on Negotiations I-KNO: Contested Knowledge Claims I-COL: Breakdown/Adaptation of Collective Action | Problem: Interactions can be viewed as simple actions, while they are often arenas of contestation over power and knowledge. Solution: These variables explicitly frame interactions as political processes, foregrounding power (I-POW) and knowledge conflicts (I-KNO) while linking the potential for collective action (I-COL) directly to actor capacity (A-DC). |

| Outcomes (O) | Ecological Sustainability, Economic Efficiency, Equity | O-PSY: Psycho-Social Well-being (stress, fear) O-CUL: Cultural Acceptability & Sustainability O-EQU: Equity & Justice O-ADA: Adaptive Capacity | Problem: An overemphasis on material or ecological outcomes leads to an incomplete evaluation of management success. Solution: These variables broaden the assessment to include the critical “hidden” social, psychological, cultural, and equity dimensions, ensuring a more holistic and accurate measure of sustainable coexistence. |

4.5. Power Dynamics: Unequal Influence and Hidden Conflicts

4.6. Synthesizing the Context: The Imperative for an Adapted SES Framework

5. The Adapted SES Framework for HWC Management in Japan

5.1. Conceptual Utility: Re-Analyzing HWC Scenarios Through the Adapted Lens

5.1.1. Scenario 1: The Systemic Strain on the Ryōyūkai System

5.1.2. Scenario 2: Satoyama Degradation and Sika Deer Conflict

5.1.3. Scenario 3: Cultural Ambivalence and Power in Bear Management

5.2. Synthesis: The Value of an Adapted Lens for Understanding and Action

6. Discussion and Implications

6.1. Discussion: Advancing the SES Framework for a Culturally Informed HWC Analysis in Japan

6.2. Policy Implications: Towards Culturally Informed and Adaptive Management

6.3. Theoretical Implications: Context, Power, and Demography in SES Analysis

6.4. Limitations of the Study

6.5. Future Research Directions

6.6. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nyhus, P.J. Human-wildlife conflict and coexistence. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2016, 41, 143–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pooley, S.; Barua, M.; Beinart, W.; Dickman, A.; Holmes, G.; Lorimer, J.; Loveridge, A.; Macdonald, D.; Marvin, G.; Redpath, S.; et al. An interdisciplinary review of current and future approaches to improving human–predator relations. Conserv. Biol. 2017, 31, 513–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knight, J. Waiting for Wolves in Japan: An Anthropological Study of People-Wildlife Relations; University of Hawaii Press: Honolulu, HI, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of the Environment, Japan. Chōjū Hogo Kanri Seisaku no Genjō to Gyōsei-jō no Sho-Taisaku ni Tsuite. 2023. Available online: https://www.maff.go.jp/j/seisan/tyozyu/higai/h_kensyu/attach/pdf/R5/r5kensyu-030.pdf (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries. Reiwa 5 Nendo Shokuryō·Nōgyō·Nōson no Dōkō/Reiwa 6 Nendo Shokuryō Nōgyō Nōson Seisaku. 2024. Available online: https://www.maff.go.jp/j/wpaper/w_maff/r5/pdf/zentaiban.pdf (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- Barua, M.; Bhagwat, S.A.; Jadhav, S. The hidden dimensions of human–wildlife conflict: Health impacts, opportunity and transaction costs. Biol. Conserv. 2013, 157, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, J. (Ed.) Culling demons: The problem of bears in Japan. In Natural Enemies: People-Wildlife Conflicts in Anthropological Perspective; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2000; pp. 145–169. [Google Scholar]

- Yamabata, N. Chiiki Shakai no Tame no Sōgō-Teki na Jūgai Taisaku: Higai Bōjo Kotaigun Kanri Shūraku Shien Kankei Kikan no Taisei-Zukuri; Nobunkyo Production Co., Ltd.: Tokyo, Japan, 2017. Available online: https://www.maff.go.jp/j/seisan/tyozyu/higai/manyuaru/sougou_tekina_jyuugai_taisaku/h29_sogo_jyuugai_taisaku-1.pdf (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- Tsunoda, H.; Enari, H. A strategy for wildlife management in depopulating rural areas of Japan. Conserv. Biol. 2020, 34, 819–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications. Reiwa 4 Nendo-Ban Kaso Taisaku no Genkyō. 2024. Available online: https://www.soumu.go.jp/main_content/000944363.pdf (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- Takeuchi, K.; Brown, R.D.; Washitani, I.; Tsunekawa, A.; Yokohari, M. (Eds.) Satoyama: The Traditional Rural Landscape of Japan; Springer: Tokyo, Japan, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi, K. Rebuilding the relationship between people and nature: The Satoyama initiative. Ecol. Res. 2010, 25, 891–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiroshige, M. Jūgai taisaku to shigen riyō. J. Rural. Stud. 2024, 31, 18–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakajima, N. Dēta de miru yasei dōbutsu no bunpu henka. In Shinrin Kankyō 2007: Dōbutsu Hanran to Mori no Hōkai; Morimoto, Y., Yasuda, Y., Eds.; Shinrin Bunka Kyokai; Asahi Shimbunsha: Tokyo, Japan, 2007; pp. 57–68. [Google Scholar]

- Takatsuki, S. Effects of sika deer on vegetation in Japan: A review. Biol. Conserv. 2009, 142, 1922–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, M.A. Overview of the structure and the challenges of Japanese wildlife law and policy. Biol. Conserv. 2009, 142, 1958–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akasaka, T.; Igota, H.; Aoki, Y. Nihon no shuryō to yasei dōbutsu kanri. In Shuryōgaku: Science of Hunting for Wildlife Management in Japan; Kaji, K., Igota, H., Suzuki, M., Eds.; Asakura Shoten: Tochigi, Japan, 2013; pp. 11–28. [Google Scholar]

- Kaji, K. Yasei dōbutsu kanri no shakai kiban no kōchiku. Wildl. Hum. Soc. 2013, 1, 13–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, K. Chiiki ga shutai to natta jūgai taisaku no korekara no kadai. Wildl. Hum. Soc. 2014, 1, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovelock, B.; Yanata, K.; Seto, Y.; Yamaguchi, M. Societal factors influencing hunting participation decline in Japan: An exploratory study of two prefectures. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2022, 35, 149–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkes, F.; Colding, J.; Folke, C. (Eds.) Navigating Social-Ecological Systems: Building Resilience for Complexity and Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. A general framework for analyzing sustainability of social-ecological systems. Science 2009, 325, 419–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakurai, R. Human Dimensions of Wildlife Management in Japan: From Asia to the World; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Kito, S. Shizen Hogo o Toi Naosu: Kankyō Rinri to Nettowāku; Chikuma Shobō: Tokyo, Japan, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, K.M.; Balvanera, P.; Benessaiah, K.; Chapman, M.; Díaz, S.; Gómez-Baggethun, E.; Gould, R.; Hannahs, N.; Jax, K.; Klain, S.; et al. Why protect nature? Rethinking values and the environment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 1462–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanzaki, N.; Ito, E. Kin-gendai no Nihon ni okeru inoshishi ryō oyobi inoshishi niku no shōhinka no hensen. Wildl. Conserv. Jpn. 1997, 2, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, M.A. Shuryō no sho-yōso o fumaeta 2014-nen chōjū-hō kaisei no hōteki bunseki. Wildl. Hum. Soc. 2015, 3, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A.; Gibson, C.C. Enchantment and disenchantment: The role of community in natural resource conservation. World Dev. 1999, 27, 629–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, P. Political Ecology: A Critical Introduction, 2nd ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Nightingale, A.J.; Ahlborg, H. Theorizing power in political ecology: The “where” of power in resource governance projects. J. Politi-Ecol. 2018, 25, 381–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. A diagnostic approach for going beyond panaceas. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 15181–15187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brondizio, E.S.; Ostrom, E.; Young, O.R. Connectivity and the governance of multilevel social-ecological systems: The role of social capital. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2009, 34, 253–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folke, C.; Hahn, T.; Olsson, P.; Norberg, J. Adaptive governance of social-ecological systems. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2005, 30, 441–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGinnis, M.D.; Ostrom, E. Social-ecological system framework: Initial changes and continuing challenges. Ecol. Soc. 2014, 19, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkes, F.; Folke, C. (Eds.) Linking Social and Ecological Systems: Management Practices and Social Mechanisms for Building Resilience; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Yeshey; Keenan, R.J.; Ford, R.M.; Nitschke, C.R. Social and ecological dimensions are needed to understand human-wildlife conflict in subsistence farming context. People Nat. 2024, 6, 2602–2617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rots, A.P. Shinto, Nature, and Ideology in Contemporary Japan: Making Sacred Forests; Bloomsbury Academic: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, D.R. Buddhist environmentalism in contemporary Japan. In Handbook of Contemporary Japanese Religio; Prohl, I., Nelson, J., Eds.; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 373–392. [Google Scholar]

- Shoji, K. Nihonjin no dōbutsu-kan to shuryō no dōkō ni kansuru kōsatsu. Jpn. J. Zoo Wildl. Med. 2008, 13, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, N.A.; Shaw, S.; Ross, H.; Witt, K.; Pinner, B. The study of human values in understanding and managing social-ecological systems. Ecol. Soc. 2016, 21, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himes, A.; Muraca, B. Relational values: The key to pluralistic valuation of ecosystem services. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2018, 35, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, J. Who defines community in community-based adaptation: Different perceptions of community between government and citizens in Ethiopia. Clim. Dev. 2023, 15, 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honda, T. Environmental factors affecting the distribution of the wild boar, sika deer, Asiatic black bear, and Japanese macaque in central Japan, with implications for human-wildlife conflict. Mammal Study 2009, 34, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akitsu, M. Gaijū kujo to iu shuryō: Shinki shuryōsha ni yoru satoyama hozen no kanōsei. In Satoyama no Gabanansu; Yoyoi, U., Ryuya, S., Eds.; Kōyō Shobō: Kyoto, Japan, 2012; pp. 147–168. [Google Scholar]

- Berkes, F. Sacred Ecology, 3rd ed.; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ingalls, M.L. Not just another variable: Untangling the spatialities of power in social-ecological systems. Ecol. Soc. 2017, 22, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, K. Hito to yasei dōbutsu no atsureki kaishō ni muketa shakai kagaku no yakuwari to kanōsei. Wildl. Forum 2010, 15, 30–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodin, Ö. Collaborative environmental governance: Achieving collective action in social-ecological systems. Science 2017, 357, eaan1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treves, A.; Karanth, K.U. Human-carnivore conOxford University Pressflict and perspectives on carnivore management worldwide. Conserv. Biol. 2003, 17, 1491–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dryzek, J.S. The Politics of the Earth: Environmental Discourses, 3rd ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Dayer, A.A.; Williams, A.; Cosbar, E.; Racey, M. Blaming threatened species: Media portrayal of human–wildlife conflict. Oryx 2019, 53, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madden, F.; McQuinn, B. Conservation’s blind spot: The case for conflict transformation in wildlife conservation. Biol. Conserv. 2014, 178, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flyvbjerg, B. Rationality and Power: Democracy in Practice; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, K. Shimokita hantō no engai mondai ni okeru nōka no fukuzatsu na higai ninshiki to sono kahensei. J. Environ. Sociol. 2007, 13, 184–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfredo, M.J.; Dayer, A.A. Concepts for exploring the social aspects of human-wildlife conflict in a global context. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 2004, 9, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dressel, S.; Ericsson, G.; Sandström, C. Mapping social-ecological systems to understand the challenges underlying wildlife management. Environ. Sci. Policy 2018, 84, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, R.L.; Paul, S.; Wiber, M.; Angel, E.; Benson, A.J.; Charles, A.; Chouinard, O.; Clemens, M.; Edwards, D.; Foley, P.; et al. Evaluating and implementing social-ecological systems: A comprehensive approach to sustainable fisheries. Fish Fish. 2018, 19, 853–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmqvist, T.; Colding, J.; Barthel, S.; Borgström, S.; Duit, A.; Lundberg, J.; Andersson, E.; Ahrné, K.; Ernstson, H.; Folke, C.; et al. The dynamics of social-ecological systems in urban landscapes: Stockholm and the National Urban Park, Sweden. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2004, 1023, 308–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Marnie, C.; Tricco, A.C.; Pollock, D.; Munn, Z.; Alexander, L.; McInerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Évid. Synth. 2020, 18, 2119–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, Y.; Ding, Y.; Zha, Z.; Okuro, T. Crises of biodiversity and ecosystem services in Satoyama landscape of Japan: A review on the role of management. Sustainability 2019, 11, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawai, M. Satoyama to dōbutsu. In Shinrin Kankyō 2007: Dōbutsu Hanran to Mori no Hōkai; Morimoto, Y., Yasuda, Y., Eds.; Shinrin Bunka Kyōkai: Tokyo, Japan, 2007; pp. 7–15. [Google Scholar]

- Kato, E.; Yano, Y.; Ohe, Y. Investigating gaps in perception of wildlife between urban and rural inhabitants: Empirical evidence from Japan. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, T.; Higashide, D.; Shichijo, T. Impact of human disturbance in Japan on the distribution and diel activity pattern of terrestrial mammals. J. Nat. Conserv. 2022, 70, 126293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, S.; DasGupta, R.; Kabaya, K.; Matsui, T.; Haga, C.; Saito, O.; Takeuchi, K. Scenario analysis of land-use and ecosystem services of social-ecological landscapes: Implications of alternative development pathways under declining population in the Noto Peninsula, Japan. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 14, 53–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of the Environment. Zenkoku no Nihon-Jika Oyobi Inoshishi no Seisoku Bunpu Chōsa ni Tsuite. 2021. Available online: https://www.env.go.jp/content/900517069.pdf (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- Bakels, J. Farming the forest edge: Perceptions of wildlife among the Kerinci of Sumatra. In Wildlife in Asia: Cultural Perspectives; Knight, J., Ed.; RoutledgeCurzon: Oxfordshire, UK, 2004; pp. 147–164. [Google Scholar]

- Hara, Y.; Sampei, Y. Minabe–Tanabe no ume shisutemu: Sono randosukēpu no tokuchō to sentei purosesu no jissai. J. Rural. Plan. Assoc. 2016, 35, 379–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garibaldi, A.; Turner, N. Cultural keystone species: Implications for ecological conservation and restoration. Ecol. Soc. 2004, 9, 1. Available online: https://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol9/iss3/art1/ (accessed on 11 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries. Chōjū Higai no Genjō to Taisaku. 2025. Available online: https://www.maff.go.jp/j/seisan/tyozyu/higai/attach/pdf/240605-88.pdf (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- Honda, T.; Kozakai, C. Mechanisms of human-black bear conflicts in Japan: In preparation for climate change. Sci. Total. Environ. 2020, 739, 140028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshita, T.; Nishizawa, H.; Sakata, R. Sono ba de shori jibie-kā no kanōsei. Jpn. J. Anim. Hyg. 2018, 43, 175–183. Available online: https://agriknowledge.affrc.go.jp/RN/2030921137.pdf (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- Kurosaki, K.; Wang, F.; Yamano, H.; Yoshida, S.; Koizumi, S.; Kobayashi, S. Yasei shika niku shori shisetsu no genjō to kadai. Nihon Chikusan Gakkaiho 2020, 91, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyoto Prefecture. Kyōto-fu dai-13-ji Chōjū Hogo Kanri Jigyō Keikakusho. 2022. Available online: https://www.pref.kyoto.jp/choujyu/documents/13th_plan.pdf (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- Whittaker, D.; Manfredo, M.J.; Fix, P.J.; Sinnott, R.; Miller, S.; Vaske, J.J. Understanding beliefs and attitudes about an urban wildlife hunt near Anchorage, Alaska. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 2001, 29, 1114–1124. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3784134 (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- Goulding, C.; Kelemen, M.; Kiyomiya, T. Community based response to the Japanese tsunami: A bottom-up approach. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2018, 268, 887–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokida, K. Nihon no shuryō oyobi chōjū hogo seido no henka to 2014-nen no chōjū hogohō kaisei. Jpn. J. Zoo Wildl. Med. 2016, 21, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, M.G.; Lavis, J.N.; Travers, R.; Rourke, S.B. Community-based knowledge transfer and exchange: Helping community-based organizations link research to action. Implement. Sci. 2010, 5, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueda, G.; Kanzaki, N.; Koganezawa, M. Changes in the structure of the Japanese hunter population from 1965 to 2005. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 2010, 15, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagasaka, M.; Yamamoto, S. Tsukino waguma hogo kanri ni okeru kiso jichitai no yakuwari to kongo no tenbō. J. Rural. Plan. Assoc. 2005, 24, S157–S162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, K.; Ichikawa, K.; Elmqvist, T. Satoyama landscape as social–ecological system: Historical changes and future perspective. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2016, 19, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massé, F. The political ecology of human-wildlife conflict: Producing wilderness, insecurity, and displacement in the Limpopo National Park. Conserv. Soc. 2016, 14, 100–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gu, F.; Sakanashi, K. Human–Wildlife Coexistence in Japan: Adapting Social–Ecological Systems for Culturally Informed Management. Conservation 2025, 5, 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/conservation5030042

Gu F, Sakanashi K. Human–Wildlife Coexistence in Japan: Adapting Social–Ecological Systems for Culturally Informed Management. Conservation. 2025; 5(3):42. https://doi.org/10.3390/conservation5030042

Chicago/Turabian StyleGu, Fangzhou, and Kenta Sakanashi. 2025. "Human–Wildlife Coexistence in Japan: Adapting Social–Ecological Systems for Culturally Informed Management" Conservation 5, no. 3: 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/conservation5030042

APA StyleGu, F., & Sakanashi, K. (2025). Human–Wildlife Coexistence in Japan: Adapting Social–Ecological Systems for Culturally Informed Management. Conservation, 5(3), 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/conservation5030042