Abstract

ROSCI0135 Bârnova-Repedea Forest, covering 12,236.20 ha, is a relatively large Natura 2000 site from Romania, though not as large as other Natura 2000 sites. However, in terms of the number of invertebrate species of community importance, with 18 species present, Bârnova Forest ranks as the fourth richest site in Romania, with the following species: Helix pomatia, Cordulegaster heros, Coenagrion ornatum, Paracaloptenus caloptenoides, Carabus variolosus, Rhysodes sulcatus, Cucujus cinnaberinus, Rosalia alpina, Morimus funereus, Cerambyx cerdo, Lucanus cervus, Bolbelasmus unicornis, Osmoderma barnabita (eremita), Parnassius mnemosyne, Zerynthia polyxena, Euphydryas maturna, Lycaena dispar, and Euplagia quadripunctaria. Bârnova-Repedea Forest can be considered a true mosaic of habitats, providing favourable conditions for the existence of these rare Natura 2000 species. The threats to the site are complex and challenging to manage.

1. Introduction

Natura 2000 is a key European conservation network aimed at protecting biodiversity across Europe. It includes both Special Protection Areas (SPAs) for birds and Special Areas for Conservation (SACs) for habitats and species [1]. The Habitats Directive and the Birds Directive (Council Directive 79/409/EEC) are the primary tools for preserving Europe’s natural habitats and endangered species [2].

Species of community importance are those that fall into one of the following categories: threatened species, at risk of extinction, except for those with a marginal distribution range in the territory and not threatened; vulnerable species, that are likely to become threatened in the near future if current pressures persist; rare species, with small populations that are not currently threatened or vulnerable but may become so; and endemic species, with a restricted geographical range, requiring special protection due to their habitat or the potential impact of exploitation on their conservation status. Invertebrate species of community importance are indicated in Annexes II, IV, and V of the Habitats Directive (92/43/EEC) [3].

The network was created to fulfil the European Union’s commitment to the Convention on Biological Diversity (1992), helping conserve natural and semi-natural sites rich in flora and fauna. The Natura 2000 network is in connection with the “Emerald network” of Areas of Special Conservation Interest and the Bern Convention [4,5] on the conservation of European wildlife and natural habitats. It was legally established in Romania by the Emergency Government Ordonnance (EGO) 57/2007 [6] on the regime of the protection of natural areas and conservation of natural habitats and wild flora and fauna in Romania.

Natura 2000, established in 1992 and gradually expanded across the EU, plays an important role in implementing international conservation policies by balancing species and habitat protection with human needs. However, its implementation has faced opposition, leading to efforts to assess and improve its effectiveness [7]. The network includes approximately 27,000 sites located across the 27 EU member states. These protected areas cover about 18.5% of the EU’s terrestrial area and over 9% of its marine area. Within this framework, over 1500 rare plant and animal species are protected [8].

Despite its success, challenges remain, including conflicting conservation objectives, lack of coordination, and limited scientific input in management plans. Effective implementation of the Natura 2000 network requires comprehensive scientific knowledge, adaptive management, biodiversity monitoring, and adequate funding [9]. The future of the Natura 2000 network is supported by the EU’s Biodiversity Strategy for 2030, which aims to protect and restore nature through a coherent network of protected areas [7].

Invertebrate species represent 75% of all described species and 95% of described animal species on Earth, with 85% of all arthropods being insects [10]. Invertebrates play multiple roles in ecosystems, particularly in forests, such as the decomposition of organic biomass (including wood), nutrient cycling, pollination, seed dispersal, maintaining soil fertility, serving as food or natural enemies for other organisms, acting as vectors, providing natural pest control, and even shaping entire ecosystems [11].

All of these functions offer numerous free ecosystem services that benefit both nature and human health, reinforcing the need for invertebrate conservation. The abundance of terrestrial insects has declined by 9% per decade since 1960 [10], with the main cause being land-use changes—particularly the conversion of natural habitats into agricultural and urban areas [11,12].

Natura 2000-protected areas may not have been consistently established with specific attention to invertebrate conservation, and these zones do not always overlap with biodiversity hotspots for arthropods [13]. Current research follows a key recommendation at the IUCN European level, which calls for species and habitat conservation by conducting inventories in Natura 2000 sites to identify priority species and develop protection strategies accordingly [14].

Romania is the EU member state with the greatest biogeographical diversity, with five of the nine bioregions present in European Union, namely Alpine, Continental, Pannonian, Pontic, and Steppic, the latter being unique to Romania. The areas of Natura 2000 sites in Romania currently cover more than 20% of the country’s land surface, compared to nearly 18.5% across the EU [15]. Over 400 Natura 2000 sites have been designated in Romania, with areas in the Iasi region preserving rare biodiversity [16] or sheltering it [17] amidst increasing anthropization. ROSCI0135 Bârnova-Repedea Forest, with 12,236.20 ha, is a relatively large Natura 2000 site. It ranks fourth in Romania for the number of invertebrate species of community importance, with 18 species, after ROSCI0069 Domogled-Cernei Valley with 27 species (62,121.30 ha), ROSCI0227 Sighişoara-Târnava Mare with 20 species (89,264.90 ha), and ROSCI0206 Iron Gates (Porţile de Fier) with 20 species (125,502.50 ha). These sites are 5–10 times larger than Bârnova Forest. Unfortunately, not all data in the Standard Data Forms (SDFs) reflect the reality. For example, the species Parnassius apollo (L.) is listed in some sites, although it has been extinct in Romania for many years. A re-evaluation, with concrete data from the field, of these data is needed. This study serves as an example in that direction. Given the increasing threats to biodiversity and the complexity of managing Natura 2000 sites, this work aims to support the development of improved conservation strategies for the Bârnova-Repedea Forest, an important part of Romania’s natural heritage.

2. Materials and Methods

Species observations were carried out over about thirty years, from 1994 to 2024, in ROSCI0135 Bârnova-Repedea Forest (Figure 1). The boundaries of the site are defined by the following coordinates: latitude: 47°1′27″ N; longitude: 27°38′50″ E. Covering an area of 12,216 ha, it is located in the North-East Development Region, spanning the counties of Iași and Vaslui, and is part of the Bârlad Plateau or the Central Moldavian Plateau (Ministry of Environment and Waters of Romania, 2015) [18]. Investigations were done every season, as much as possible every month.

Figure 1.

Localization of ROSCI0135 Bârnova-Repedea Forest in Romania and images of favourable habitats for invertebrate species of community importance (Natura 2000) occurring in the site.

The majority of habitats favourable to the existence of Natura 2000 species were investigated as much as possible. Negative impacts on species and their favourable habitats have been retained. As protected species, they were not collected, but only photographed in their natural habitats. Macro images were taken using a Canon 100 mm f/2.8 Macro USM lens attached to a Canon 60D digital camera (Canon Inc., Tokyo, Japan). All the insect pictures were made by the first author, except the ones with Paracaloptenus caloptenoides, made by Ionuţ Iorgu, and the ones with Coenagrion ornatum, Bolbelasmus unicornis, and Cucujus cinnaberinus larva, made by Cosmin Manci.

3. Results

In this chapter, a detailed overview of 18 invertebrate species protected under the Natura 2000 framework that are found in Bârnova Forest is presented. The descriptions highlight the specific characteristics, habitat preferences, and conservation status of each species. Some appearance and morphological features can be found in the Supplementary Materials (Table S1). The potential threats these species face, including habitat destruction, climate change, and human activities such as deforestation and pesticide use were also documented. Thus, the importance of Bârnova Forest as a key site for the preservation of these invertebrates was emphasized, along with the need for continued protection and monitoring efforts to conserve their habitats.

3.1. Helix pomatia Linnaeus, 1758 (Species Code 1026) (Mollusca: Gastropoda: Helicidae) (Roman Snail, Burgundy Snail)

H. pomatia (Figure 2a) prefers habitats such as temperate forests and shrublands, particularly areas with high humidity, in light forests and brushes, as well as open spaces like meadows, roads, clearings, orchards, gardens, hedges, vineyards, and banks of flowing waters.

Figure 2.

(a) Helix pomatia, (b) Cordulegaster heros ♂, (c) Coenagrion ornatum ♂, (d) Paracaloptenus caloptenoides ♀, (e) Paracaloptenus caloptenoides ♂, (f) Carabus variolosus ♀, (g) Rhysodes sulcatus, (h) Cucujus cinnaberinus, (i) Cucujus cinnaberinus, larva, (j) Rosalia alpina ♂, (k) Morimus funereus ♂, (l) Cerambyx cerdo ♂, (m) Cerambyx cerdo, ♀ laying eggs.

For egg laying, it needs loose soil which is also used for shelter during hibernation and aestivation. The snail is capable of creating a calcareous epiphragm to seal the shell. It can live to 20–35 years, though in the wild, it typically survives up to 10 years. This species is widespread in central and eastern Europe [19] and is relatively common throughout Romania, particularly in plain areas up to 500 m altitude. While it prefers hilly regions, it can also be found in mountainous regions up to 1800 m, and even higher in the Alps [20]. In the Bârnova Forest it can be found in open spaces such as roads, clearings, and marginal areas of the forest.

It can be confused with Helix lucorum Linnaeus and Helix lutescens Linnaeus, both species being present in the site. Helix thessalica Boettger looks very similar to H. pomatia but is not present in the studied area [21]. Living specimens can be found normally from April to July, and even to September in favourable years. The period can differ each year due to climatic variations, which have become more pronounced in recent years. The shells of the dead individuals can be found throughout the entire year. They are more active in the morning and on rainy days, and more difficult to find during extended hot periods without rain. It is an edible species, with the main threats being harvesting for consumption and habitat destruction. In Bârnova Forest, we did not observe significant pressure when collecting this species; however, the local traffic on the roads, the forestry works, and the use of pesticides on the nearby crops could affect the population.

H. pomatia is a species listed in Annex V of the EU Habitats Directive (Natura 2000). It has an LC (Least Concern) status in the global IUCN Red List of Threatened Species [19] and in the European IUCN Red List of Non-marine Molluscs [22]. In the Draft Carpathian Red List of Molluscs (Mollusca) [23], it also has LC status. It is mentioned in Annex III of the Bern Convention [4], being also listed in Annex 5A of EGO 57/2007 [6]. H. pomatia is not listed in the Standard Data Form (SDF) Natura 2000 for ROSCI0135.

3.2. Cordulegaster heros Theischinger, 1979 (Species Code 4046) (Odonata: Cordulegasteridae) (Balkan Goldenring)

C. heros (Figure 2b) is found near clean mountain and hilly streams in shady forest areas. The larvae prefer a stony to sandy substrate in forest streams and small rivers, feeding mostly on insect larvae but also on fish larvae. It is an endemic species of the southeastern area of Europe [24]. In Romania, it has been reported in the southeastern part of the country, particularly in Banat [25]. The presence of this species in Bârnova Forest is unexpected, as it represents the easternmost point in the species’ range, hundreds of kilometres away from other populations in Romania. The Museum of Natural History in Iaşi holds seven specimens collected between 1974 and 1990 from the Bârnova area [26], and more recent data confirm the presence of this species in this site. The flight period of the adults is from June to August. The larvae can move in deeper moist sediments to survive in the drought periods [27]. C. heros is a rare species in the Bârnova Forest, with a very scattered distribution. The main issue is the rarity of its specific habitats and the potential destruction of them, particularly due to deforestation, alteration of the water quality, accumulation of pesticides in the waters, disturbance of the stream substrate, and human use of the water. Climate change with prolonged periods of droughts can be a serious problem also in Bârnova Forest, along with wood harvesting. The result could be the desiccation of streams and alteration of the specific habitats. Local traffic on the roads near the forest streams can kill the adults flying in search for prey, mating, and establishing territories. The collection of specimens might also pose a threat, even for trade, with the starting price for Cordulegaster on eBay being at around USD 10.

C. heros is a species listed in Annexes II and IV of the EU Habitats Directive (Natura 2000) [3]. It has LC status in the global IUCN Red List of Threatened Species and in the IUCN Europe Red List of Threatened Species [27,28], NT (Near Threatened) in the European Red List of Dragonflies [29], VU (Vulnerable) in the IUCN Red List of Mediterranean Dragonflies [30], NT in the Draft Red List of Dragonflies of the Carpathians [31], and is also present in Annex I of Resolution 6 (1998) of the Bern Convention (revised in 2011) [4]. It is listed in Annexes 3 and 4A of EGO 57/2007 [6].

3.3. Coenagrion ornatum (Selys, 1850) (Species Code 4045) (Odonata: Coenagrionidae) (Ornate Bluet)

C. ornatum (Figure 2c) are typically found in sunny areas near slow-flowing, shallow, muddy waters with a calcareous substrate, streamlets, and ditches, often surrounded by hygrophilous herbaceous vegetation [32,33]. The distribution range of C. ornatum extends from Europe—where it is more frequently found in the Balkans—to Western Asia [24]. In Europe, it is primarily found especially in the east and southeastern regions. However, in recent years, the species has shown a significant decline in the western and northwestern parts of the continent, largely due to habitat destruction. A reduction of approximately 25% in its distribution area is expected [32,33]. In Romania, it has been recorded in several areas in Banat, Maramureş, southern Transylvania, Dobrogea, etc. [20,25]. The collection of the Natural History Museum in Iaşi holds 26 specimens obtained in 1985 from the Bârnova area [26]. The flight period of the adults is from May to August. In Bârnova Forest, the presence of C. ornatum is strongly corelated with the occurrence of the waters needed for larvae development. The main threats to the species include the destruction of these scarce and fragile habitats caused by prolonged droughts, stream desiccation, water extraction for human use, and the degradation of the hygrophilous herbaceous vegetation. Additional threats include the accumulation of pesticides in the aquatic environments, and the effects of climate change, such as reduced snowfall in winter, decreased rainfall in other seasons, and extended periods of drought. Local road traffic near aquatic habitats can be a threat to flying adults, often resulting in direct mortality.

C. ornatum is a species listed in Annex II of the EU Habitats Directive (Natura 2000) [3]. It has LC status in the global IUCN Red List of Threatened Species [32] and in the IUCN Europe Red List of Threatened Species [28,33], NT in the European Red List of Dragonflies [29], NT in the IUCN Red List of Mediterranean Dragonflies [30], NT in the Draft Red List of Dragonflies of the Carpathians [31], and is also present in Annex I of Resolution 6 (1998) of the Bern Convention (revised in 2011) [5]. It is listed in Annexes 3 and 4A of EGO 57/2007 [6].

3.4. Paracaloptenus caloptenoides (Brunner von Wattenwyl, 1861) (Species Code 4053) (Orthoptera: Acrididae) (Balkan Pincer Grasshopper)

P. caloptenoides is a micropterous grasshopper (Figure 2d,e). This species does not stridulate. It is a grasshopper found along the edge and in clearings of oak forests, in both plain and hilly regions. It prefers areas with low vegetation, such as xeric grasslands and limestone habitats, being a geophilous, thermophile species [20,34,35]. It was found from Central Europe to Asia Minor [35] with an estimated area of occupancy between 1200 and 3500 km2 in Europe, and 800 and 1800 km2 in EU28. The populations are severely fragmented, small, isolated, and in decline [36]. In Romania, it is a very rare species, reported to occupy a total area of occupancy of just 44 km2 in the south and east of the country, with few populations in Banat, Dobrogea, and Moldova, all in decline due to decreasing habitats [35]. It was first mentioned in Bârnova Forest by Ionuţ Iorgu and Elena Iorgu [34]. Nymphs hatch in April–May, and the adults can be found from July to October. It is a rare species in Bârnova Forest, with the main threats being the scarcity of the specific habitats and their destruction due to silvicultural activities, afforestation, local overgrazing, shrub growth, habitat transformation, and the use of pesticides.

P. caloptenoides is a species listed in Annexes II and IV of the EU Habitats Directive (Natura 2000) [3]. In the IUCN Europe Red List of Threatened Species [36] and the European Red List of Grasshoppers, Crickets and Bush-crickets [37], it has the status NT in the IUCN Red List Category (Europe) and VU in the IUCN Red List Criteria (EU 28). In the Red List of Grasshoppers, Bush-crickets and Crickets (Orthoptera) of the Carpathian Mountains [38], it has the CR (Critically Endangered) status. In the Red List of Invertebrates of Romania [35], it has the status EN (Endangered), being also present in Annex I of Resolution 6 (1998) of the Bern Convention (revised in 2011) [5]. It is listed in Annexes 3 and 4A of EGO 57/2007 [6]. P. caloptenoides is not listed in the Standard Data Form (SDF) Natura 2000 for ROSCI0135.

3.5. Carabus variolosus Fabricius, 1787 (Species Code 4014) (Coleoptera: Carabidae)

Unlike other species of the genus Carabus, C. variolosus (Figure 2f) is a hygrophilous, stenotopic hygrobiont species (Hygrocarabus) [39,40], typically found on the stony banks of flowing streams and in swampy areas in wooded regions. It prefers humid deciduous forests and avoid the acidic soils of coniferous forests. It is a glacial relict species with very limited dispersal ability [41]. Adults are especially active in the evenings and at night, and may enter in the water in search of molluscs, crustaceans, worms, and aquatic insects on which they feed. The larvae also hunt the prey in the water [20,35,41,42,43]. C. variolosus is a European species with fragmented, small, and declining populations [41]. In Romania it is found from hilly areas up to altitudes of 1700 m, preferring mountainous regions. Within its specific habitats, it is not considered a rare species [20,35,40,44]. The adults can be found from May (reproductive period) to October, with a possible diapause from July onwards. In Bârnova Forest, the species is found in specific habitats with flowing streams and in swampy areas. The main threats are the destruction of these habitats due to deforestation and silvicultural activities, including the use of specific machines, tractors, and horses on the river beds. The adults hibernate in the rotting wood of trunks or logs in or near water, or in the soil from the same area. These places also serve as sites for pupation. Removing the rotting wood from these areas and ground silvicultural activities can also have a negative effect on the very vulnerable small populations. Other pressures include periods of droughts, stream desiccation, water usage by humans, and climate change leading to less snow in the winters, reduced rainfall in other seasons, prolonged drought periods, and accumulation of pesticides in the waters. The adults can also be found on the roads close to the waters and may be killed by evening and nocturnal traffic. The collection of specimens could pose a threat, including through trade: a pair of C. variolosus can be on eBay at a price of around USD 20. C. variolosus is an indicator of undisturbed woodland brooks and swamps, and the presence of this usually alpine species in Romania is a very interesting sign of the diversity of the ecological conditions in the Bârnova Forest site.

C. variolosus is a species listed in Annexes II and IV of the EU Habitats Directive (Natura 2000) [3]. In the Red List of Invertebrates of Romania [35] it has the status VU, being also present in Annex I of Resolution 6 (1998) of the Bern Convention (revised in 2011) [5]. It is listed in Annexes 3 and 4A of EGO 57/2007 [6].

3.6. Rhysodes sulcatus (Fabricius, 1787) (Species Code 4026) (Coleoptera: Carabidae)

R. sulcatus (Figure 2g) is a relict of primeval forests, a stenotopic obligate saproxylic species, found in old deciduous and mixed forests, both as larvae and adults in decaying wood under the bark of old trees with a diameter greater than 60 cm, usually more than 100 years old, and affected by fungi [45,46]. The larvae feed on the moist, rotting wood of dead trees, making 1.5–2 mm diameter tunnels [45]. The adults can aggregate in groups that often include larvae [46]. Pupation occurs in place in the summer in the sapwood, the life cycle being two years. They can hibernate both as pupae and adults in the galleries and crevices in the wood, as well as under loose bark. Young adults appear in June to August [45,47,48]. The distribution area is from western (just in the Pyrenees and southern France), central, and eastern Europe, to Caucasus and Asia Minor, but with rare small populations and severely fragmented distribution [20,35,45,46,47]. The estimated area of occupancy is less than 500 km2, with limited dispersal ability and a decline in populations due to loss of old trees and decaying wood, and the removal from forests of large trees and old logs [48]. In Romania, it is a rare indicator species of forests with old trees with decaying wood, with small isolated populations in the montane forests [20,35]. The adults can be active from May to October, but they can be found together with larvae in the decaying wood throughout the entire year. In Bârnova Forest, R. sulcatus is not a common species, but can be found in big decaying moist wood trunks, on the wet soil, which support myxomycetic and fungal growth, with a high diversity of fungi. The species’ preference for this specific microhabitat highlights the main threat it faces: the removal of large fallen tree trunks from the forest floor. The presence of this relict species in the site indicates that the Bârnova Forest has, or once had, environmental conditions similar to those of a primeval forest. The use of pesticides may also pose a threat, as well as changes that disrupt the humid microclimate in areas favourable for the species’ presence and development. Drought periods, desiccation, human use of water resources, and climate change, characterized by reduced snowfall in winters, less rainfall in the rest of the seasons, and prolonged drought periods, can negatively impact populations of R. sulcatus.

R. sulcatus is a species listed in Annex II of the EU Habitats Directive (Natura 2000) [3]. It has DD (Data Deficient) status in the IUCN Europe Red List of Threatened Species [48] and EN in the European Red List of Saproxylic Beetles [12,14]. In the Red List of Invertebrates of Romania [35], it has the status EN, being also present in Annex I of Resolution 6 (1998) of the Bern Convention (revised in 2011) [5]. It is listed in Annexes 3 and 4A of EGO 57/2007 [6].

3.7. Cucujus cinnaberinus (Scopoli, 1763) (Species Code 1086) (Coleoptera: Cucujidae)

C. cinnaberinus (Figure 2h) is a stenotopic, obligate saproxylic species [20,40,49,50]. In Romania, there are historical records of C. haematodes Erichson [51], but this species is found normally in mountain and subalpine areas [40,52], and has not yet been recorded in Bârnova Forest. Both species are very similar, but in C. haematodes, the pronotum and mandibles are entirely red, with only the mandibular denticles being darker [41,53]. C. cinnaberinus has a very cryptic lifestyle. Both larvae and adults develop beneath the bark of old, dead, decaying trees, both deciduous and coniferous species. Both adults and larvae are saproxylophagous, as well as necrophagous and predatory. The larvae feed on bark and cambium, and they can also act as scavengers and are cannibalistic. Adults are typically observed from May to June on the bark of the trees where they complete their life cycle, but they can also be found earlier in the year, during March and April, under the bark. The adults can be seen flying in the evening. Larval development can last up to two years. Both adults and full-grown larvae hibernate under the bark. Pupae can be found in July–August; the pupal chambers are oval, made from wood chips, and located beneath the bark. Young adults emerge in July–August and can be observed under the bark even in the winter. Generally, in June to July, the adults are not seen on the bark. Larvae can be seen under the bark all year. C. cinnaberinus is a very opportunistic species; it can be found under the bark of a wide variety of tree genera, including Quercus, Fagus, Betula, Populus, Acer, Tilia, Ulmus, Salix, Fraxinus, Alnus, Prunus, Robinia, Juglans, Sambucus, Picea, Pinus, Abies, and others. However, it may exhibit local preferences for certain host species [53,54,55,56].

Distinguishing between the larvae of C. cinnaberinus (Figure 2i) and C. haematodes in the field is challenging. However, the larvae of Pyrochroa, which are often found in the same microhabitats, can be differentiated by their straight terminal cerci [49,50,57].

C. cinnaberinus is an endemic European species, with the distribution range extending from Spain to Italy, and from Sweden to Ukraine, occurring from the lowlands up to elevations above 1500 m. Its main populations are concentrated in central Europe, while it is in decline in the surrounding regions, particularly in the western and southern parts of its range [49,53]. It is a rare species in Romania, particularly in the region of Moldova. However, available data may underestimate its presence due to the difficulty in observing adults and the need for active methods to locate both larvae and adults beneath the bark [20,35,56]. Because of the very hidden way of life, under the bark of dead trees, of both larvae and adults, it is a little more difficult to find exemplars of C. cinnaberinus in Bârnova Forest, and an active search is necessary. Adults can occasionally be seen on the bark of the tree host, but not in the middle of the summer. It is often possible to find numerous individuals, especially larvae, beneath the bark, where they may occur in gregarious groups. The main threats to the species include deforestation, favourable habitat fragmentation, and the removal of the standing and fallen big, old, veteran, decaying host trees, including branches and logs from the forest floor. The use of pesticides can be a threat, especially for the adults. Additionally, saproxylic Coleoptera are becoming increasingly popular among beetle collectors. A single specimen of C. cinnaberinus can be found on platforms like eBay for around USD 10, while other species from the Cucujidae family can reach prices of up to USD 50 each. C. cinnaberinus is a species listed in Annexes II and IV of the EU Habitats Directive (Natura 2000) [3]. It has NT status in the global IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, and NT in the European Red List of Saproxylic Beetles [12,14]. It is present in Annex II of the Bern Convention [4] and in Annex I of Resolution 6 (1998) of the Bern Convention (revised in 2011) [5]. In the Red List of Invertebrates of Romania, it has NT status [35], and is listed in Annexes 3 and 4A of EGO 57/2007 [6].

3.8. Rosalia alpina (Linnaeus, 1758) (Species Code 1087) (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae) (Rosalia Longicorn)

R. alpina is a stenotopic, obligate saproxylic species (Figure 2j). Adults are typically observed from June to September, mainly on old, sun-exposed beech trunks, but also on logs and piles of freshly cut logs [20,39,40,58]. They are capable of flying around at least to a distance of two kilometres, and lay their eggs in cracks in the bark of old trees, as well as in crevices in dead wood on the ground but exposed to the sun in all situations [59]. Its larvae develop over a period of 2 to 4 years in standing or fallen decaying big beech trunks, with a diameter greater than 20 cm, typically found in old beech forests. Most galleries occur at a depth of 4–10 cm within the wood. It can also develop as a polyphagous species in mixed forests in Fraxinus excelsior L., Acer pseudoplatanus L., Ulmus, Carpinus, Tilia, Castanea, Juglans, Quercus, Salix, Alnus, and Crataegus [35,60]. Before the last winter, the larvae migrate toward the cortex, and the pupation occurs in cavities near the surface of the dead wood, in the spring or in early summer [59].

The distribution area extends from Europe to the Urals and to the Caucasus, as well as Asia Minor and northern Africa [20,35,59]. Although there are many records of its presence, the species is experiencing a decline due to the loss of its specific habitat, a trend that is particularly pronounced in the Mediterranean region [61].

In Romania, it can be found in beech and mixed forests, mainly in the lower mountain areas [20,35]. In Bârnova Forest, R. alpina is relatively uniformly distributed; during a one-day excursion, it is possible to see a few specimens, and even more in some years, usually on the trunks of large beech trees. Being an easily recognizable species, it is possible to find the remains of the exoskeletons of dead adults at the base of the host trees, in and on the surface of the litter. The main threats are deforestation and the removal of the standing and fallen large, veteran beech trees. The stacking of extracted timber can become a veritable ecological trap for the egg-laying females. These stored trunks must remain in nature for at least four years to allow the deposited eggs a chance to became adults. Being a large, charismatic species, the collection of specimens might pose a threat. Different colour aberrations are used in trade for exchange with different tropical beetles and a pair of R. alpina can be found on eBay at a price of around USD 40. The adults can be killed on the roads and the use of pesticides can be also a threat, especially for the adults.

R. alpina is a species listed in Annexes II and IV of the EU Habitats Directive (Natura 2000) [3]. It has VU status in the global IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, LC in the IUCN Europe Red List of Threatened Species, LC in the IUCN Mediterranean Red List of Threatened Species [61], LC in the European Red List of Saproxylic Beetles [12,14], and EN in the Carpathian List of Endangered Species [62]. It is present in Annex II of the Bern Convention [4] and in Annex I of Resolution 6 (1998) of the Bern Convention (revised in 2011) [5]. In the Red List of Invertebrates of Romania, it has VU status [35] and is listed in Annexes 3 and 4A of EGO 57/2007 [6].

3.9. Morimus funereus Mulsant, 1863 (Species Code 1089) (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae)

Some authors consider that M. asper funereus is found in Romania, but from the protective point of view, we consider it M. funereus (sensu lato) [63,64]. M. funereus (Figure 2k) is a silvicolous, stenotopic, obligate saproxylic species, found from the sea level up to 1800 m, in old deciduous and mixed forests, dominated by beech and oak, with old stumps and decaying wood on the ground. It is rarely found it in coniferous forests [64,65]. Females lay their eggs in the dead wood of large standing trees with bark still attached, trunks on the ground, and large stumps. They lay one egg in each individual pit shaped with the mandibles [65], using inclusively the debilitated trees containing developing larvae from previous years. The larvae develop over three to four and even five years, excavating subcortical galleries in decaying wood from fallen trunks, stumps, and old, thick roots, especially in beech (Fagus) and oak (Quercus), but also in other deciduous (Alnus, Acer, Populus, Castanea, Platanus, Ulmus, Salix, Tilia, and Carpinus) and coniferous (Picea and Abies) trees, being a polyphagous species [20,35,64,65]. Overwintering adults emerge in spring and can reproduce in the second year. Adults are found from April to October on tree trunks, logs, and even on the ground, feeding on sap from wounded trees. They are more active in the evening and in the night. Adults can enter into diapause in August.

The distribution area extends from Europe to Turkey but, being flightless, it has a very limited dispersal capacity. Populations are often fragmented and not all suitable habitats are occupied [64,65]. It is widespread throughout Romania, where it finds favourable conditions, especially in the beech and broad-leaf forests, including Danube Delta [20,35]. In Bârnova Forest, M. funereus is a relatively common species, usually seen on the trunk of big trees, especially at the base, but also on the soil. Being more active in the evening and in the night, we must search for the specimens, although it is possible to see them active in pairs. An easily recognisable species, we can find them at the base of the host trees, and in and at the surface of the litter, and the remains of the exoskeletons of the dead adults. The main threats are deforestation and the removal of the standing and fallen big, veteran host trees, including branches and logs from the forest soil. Fragmentation of the favourable habitats can be a significant problem, as the adults have a very low dispersal capacity and are unable to fly. M. funereus are attracted by damaged trees, recently cut wood, and piles of wood, which can become ecological traps for the egg-laying females if the timber is removed from the forest and used before the larvae finish the life cycle to became adults. Being a large, attractive beetle species, the collection of specimens might pose a threat. One exemplar of M. funereus can be found on eBay at a price of around USD 10–15. The adults can be killed on the roads and the use of pesticides can be also a threat, especially for the adults.

M. funereus is a species listed in Annex II of the EU Habitats Directive (Natura 2000) [3]. It has VU status in the global IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. It is present in Annex I of Resolution 6 (1998) of the Bern Convention (revised in 2011) [5]. In the Red List of Invertebrates of Romania, it has VU status [35] and is listed in Annexes 3 and 4A of EGO 57/2007 [6].

3.10. Cerambyx cerdo Linnaeus, 1758 (Species Code 1088) (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae) (Cerambyx Longicorn, Greater Capricorn Beetle)

C. cerdo (Figure 2l,m) is a stenotopic, obligate saproxylic species with a polyphagous range of tree hosts, from Quercus spp. to Fagus, Ulmus, Platanus, Fraxinus, Castanea, Salix, Juglans, and Prunus. The larvae develop mainly in old oak trees with a diameter of over half a meter. Isolated veteran trees are attacked in the fringe zone, roadsides, glades, natural parks, etc. Adults are found mainly on attacked trees, in the canopy, not too far from the host trees where the larvae develop. Attacked trees have visible big oval holes, with 3 cm length and 1.5 width, with wood meal and red-coloured interior sides, created by the larvae on the trunk and thick branches. Attacked trees can survives for long periods of time, up to decades. The females lay their eggs in cracks and crevices in the bark of old, solitary, sun-exposed trees (Figure 2m). The larvae create galleries that contribute to the colonisation of the dead wood by other saproxylic species. The development of the larvae lasts 3–5 years. In the first year, the larvae feed on phloem, under the bark, and from the second year onward, they move into the xylem, in the wood, creating an irregular design of larval galleries. Areas of loose bark on attacked trees have a characteristic appearance, with large, zigzagging galleries. Pupation occurs from May to June, in an escape gallery, dug to the surface of the trunk, with the adult staying in the pupation chamber in the winter until the next spring. The adults emerge from June to September and they are more active in the evening and in the night, flying no more than 500 m around the host tree. They mate in the summer and feed on oak sap and fruits, living up to two months [20,35,39,58,66,67,68,69].

The distribution area extends across most of Europe (becoming rare or absent in the north and southwest), the Caucasus, North Africa, Middle East, and northern Iran, from sea level up to 1000 m (2000 m in the southern Atlas Mountains). Despite such a large area, the species are in fact found in small populations that are in decline, due to their dependency on a very specific and highly fragmented habitat, with veteran trees, that are becoming scattered with very low densities, and are more and more rare year after year. The rate of regeneration of this very specific habitat is also very low [35,68,69]. In Romania, it is still a relatively widespread species, being mainly dependent on the presence of large, veteran, old oaks [20,35]. In Bârnova Forest, they can usually be found on and around the big oak trees, on the bark and on the big branches in the canopy. Fortunately, in Bârnova Forest, very large, old, veteran oak trees can still be found, with ages ranging from one to six hundred years. Adults of C. cerdo are more active in the evening but also can be seen during the daylight walking on the trees, mating, flying in the canopy and around the trees, and staying in holes in the wood. Other large and rare Cerambyx species occurring in Romania, C. miles Bonelli, C. welensii (Küster), and C. nodulosus Germar, are not present in Bârnova Forest. In this site, C. cerdo can be confused only with the smaller C. scopolii Fuessly, which is a frequent species in the forest. Being an easily recognisable species, it is possible to find the remains of dead adults’ exoskeletons at the bases of host trees, both in and on the surface of the litter. The main threats are deforestation and the removal of the standing, big, veteran oak trees. Some of these large oak trees, several hundred years old and hosting colonies of C. cerdo, are located along roadsides, and a few of them have unfortunately been cut down for road safety reasons. Fragmentation of favourable habitats results in increasing isolation of populations, as the adults have a limited capacity for dispersal. Especially in the evening, adults of C. cerdo can be seen attracted to concrete lighting poles along roadsides, which act as a lighting trap. Being a big, imposing beetle species, the collection of specimens might pose a threat. Saproxylic Coleoptera tend to be more popular with beetle collectors. A single exemplar of C. cerdo can be on eBay for around USD 10–15. The adults can be killed on the roads and the use of pesticides poses an additional threat, especially for the adult beetles.

C. cerdo is a species listed in Annexes II and IV of the EU Habitats Directive (Natura 2000) [3]. It has VU status in the global IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, NT in the IUCN Europe Red List of Threatened Species, LC in the IUCN Mediterranean Red List of Threatened Species [69], LC in the European Red List of Saproxylic Beetles [12,14], and VU in the Carpathian List of Endangered Species [62]. It is present in Annex II of the Bern Convention [4] and in Annex I of Resolution 6 (1998) of the Bern Convention (revised in 2011) [5]. In the Red List of Invertebrates of Romania, it has VU status [35] and is listed in Annexes 3 and 4A of EGO 57/2007 [6].

3.11. Lucanus cervus Linnaeus, 1758 (Species Code 1083) (Coleoptera: Lucanidae) (Stag Beetle, European Stag Beetle, Greater Stag Beetle)

L. cervus (Figure 3a,b) is a stenotopic, obligate saproxylic species [20,39,40,70], with a polyphagous range of host trees, including the common Quercus spp. as well as Fagus, Ulmus, Fraxinus, Castanea, Salix, Populus, Tilia, Aesculus, Pirus, Alnus, Prunus, and even Pinus. Adults emerge from the ground usually in April to May and can be observed until August to September, mainly on the trunks of the old isolated oaks from open areas, in their canopies and flying nearby. Dispersal distances reach up to 800 m for males and 300 m for females [71]. Adult feed on sap runs on tree trunks, on sugary substances, and on the fruits. After mating, females lay the eggs in galleries 70–100 cm deep, dug in the soil, around the tree roots of standing dead trees and in moist decaying, rotting wood. The species prefers isolated trees in the border zone, roadsides, glades, and similar habitats. Females possess a mycangium from which they deposit yeast around the eggs; the larvae feed on this yeast, which is essential for cellulose digestion. Females die in the soil after the last oviposition.

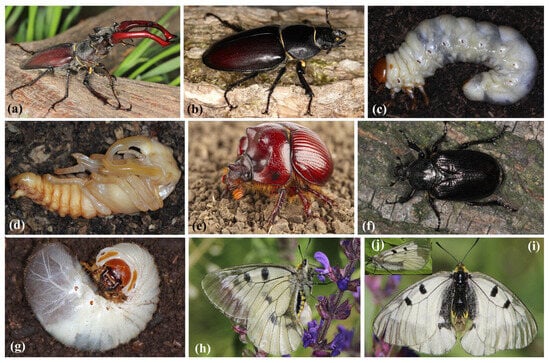

Figure 3.

(a) Lucanus cervus ♂, (b) Lucanus cervus ♀, (c) Lucanus cervus, larva, (d) Lucanus cervus, ♂ pupa, (e) Bolbelasmus unicornis ♂, (f) Osmoderma barnabita ♀, (g) Osmoderma barnabita, larva, (h) Parnassius mnemosyne ♀ ventral, (i) Parnassius mnemosyne ♀ dorsal, (j) Parnassius mnemosyne ♂.

Larval development lasts 2–6 years, through three instars. The larva has a stridulatory apparatus on the second and third pairs of legs. The full-grown larva (Figure 3c) moves up to 20 cm toward the surface of the soil and pupates at the end of the summer. The male pupa is easily recognizable by his very large mandibles (Figure 3d). The main predators of larvae and pupae are the wild boar (Sus scrofa Linnaeus) and the badger (Meles meles (Linnaeus)), while adults are also eaten by various birds and mammals. Adults appear in autumn but overwinter in the soil and emerge from the ground in the following spring. Adults live around 2–3 months (up to 200 days when fed in captivity) [70,71,72,73,74,75]. L. cervus is found from the sea level up to 2000 m and is distributed throughout Europe. However, it is in decline in the northern and central regions, while it remains more common in the southern and southeastern parts, extending to the Caucasus, Middle East, Asia Minor, Turkey, Syria, and western Kazakhstan. The species is also in decline in the eastern part of the area, mainly due to habitat loss [70,72,73,74,75]. In Romania, it is still a relatively widespread species where conditions are favourable for its development, including in the Danube Delta, and is currently considered not threatened [20,74]. L. cervus is a common species in Bârnova Forest, and it is almost impossible, even in a short trip inside, not to see a few individuals. They are more active in the evening, on and around the big oak trees, but can also be seen during the daylight on the bark, on the soil, and occasionally even flying. Smaller L. cervus females can be confused with the smaller lucanid species Dorcus parallelipipedus (Linnaeus), a common species found in the site. Being an easily recognisable species, it is possible to find the remains of dead adults’ exoskeletons at the base of host trees, both in and on the surface of the litter. The main threats are deforestation, the removal of the large, veteran standing oak trees, and the disappearance of the large dead wood from the inside of the soil. Some of these large oak trees, several hundred years old and hosting colonies of L. cervus, are located along roadsides, and a few of them have unfortunately been cut down for road safety reasons. Fragmentation of favourable habitats results in the increasing isolation of populations, as adults have a limited capacity for dispersal. The decline of stag beetles can be explained by the loss of habitat continuity, particularly the absence of large oak trees in open to semi-open areas, as well as the lack of sufficient underground dead wood. Even though L. cervus can be found in small woodlands, relatively large woodlands—over 100 hectares—are more suitable for preserving stag beetle populations. Especially in the evening, adults of L. cervus can be seen attracted to concrete lighting poles along roadsides, acting as a lighting trap. Being a large and imposing beetle species, the collection of specimens might pose a threat. Some studies suggest that climate change—particularly warmer winters—has led to a shorter larval period, resulting in smaller adults. Smaller females lay fewer eggs, which negatively affects the population [71]. Stag beetles are very popular among beetle collectors, with the price of a single male on eBay sometimes around USD 50 and even around USD 100–200 for few specimens. Although L. cervus is an emblematic flagship species for wildlife conservation in Europe, it is not included in CITES. However, its collection and sale have been banned in some countries such as Belgium, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom [74]. Adults can be killed on the roads, and the use of pesticides also poses a threat, especially to adult beetles. The largest Hymenoptera species from Europe, the solitary wasp Megascolia maculata (Drury), whose larvae feed as parasitoids on the L. cervus larvae, is present in Bârnova Forest. This charismatic wasp species is included in the Red List of Invertebrates of Romania, with the VU status [76]. As an active protection method, building log piles, with some wood buried in the soil and left in nature for years, can help the populations of stag beetles and other rare insects, including the rare and threatened saproxylic species.

L. cervus is a species listed in Annex II of the EU Habitats Directive (Natura 2000) [3]. It has NT status in the IUCN Europe Red List of Threatened Species [72], LC in the IUCN Mediterranean Red List of Threatened Species [73], LC in the European Red List of Saproxylic Beetles [12,14], and EN in the Carpathian List of Endangered Species [62]. It is present in Annex III of the Bern Convention [4] and in Annex I of Resolution 6 (1998) of the Bern Convention (revised in 2011) [5]. It is listed in Annexes 3 and 4A of EGO 57/2007 [6].

3.12. Bolbelasmus unicornis (Schrank, 1789) (Species Code 4011) (Coleoptera: Geotrupidae)

B. unicornis (Figure 3e) prefers Quercus spp. deciduous forests with open areas, steppe or forest–steppe meadows at the edges of oak forests, shrubby vegetation, heaths, and glades [20,40]. Adults dig deep vertical galleries in the ground beneath trees, about 5–60 cm in depth with a 1 cm diameter opening, surrounded by excavated soil. They spend almost all their time underground. Adults can be seen flying from May to September, at a height of 20–50 cm above the ground, sometimes hovering in the same place. This usually occurs after heavy rains that moisten the soil to a depth of at least 30 cm. When captured, they squawk vigorously by rubbing their abdominal tergites against their wings. Both females and males fly during a short interval of 30 and 60 min after sunset, preferring a temperature around 21 °C. They sometimes occur in big numbers, exhibiting gregarious behaviour. Adults feed on the sporocarp of hypogeous fungi (Tuber, Rhizopogon, Peziza, and Glomus) and on the mycorrhizal roots of shrubs or trees. Unfortunately, no immature stages of B. unicornis are known, so nothing is confirmed about the larvae; however, we can speculate that they feed on the soil humus as do related species. Judging by the aged adults found in spring, it is assumed that they can overwinter as adults. The distribution area of B. unicornis includes twenty European countries, ranging from the southern part of the central part of Europe (from Warsaw southwards), from Germany and northern Italy in the west, to Belarus (northernmost point) and Ukraine in the east, and to Bulgaria, Albania, and European Turkey in the south. It also extends to Denizli in the Asian part of Turkey at altitudes from 20 to 800 m [77,78,79,80]. It is a relatively rare recorded species in Romania, probably because the adults are active only shortly after sunset, are occasionally seen during the day, and have an underground lifestyle that makes them difficult to find [20,35,77,78]. Many locations are waiting to be discovered, with Romania lying at the centre of the distribution area of B. unicornis. Is not an easy species to be found in Bârnova Forest, due to the rarity of the visible adults and its cryptic lifestyle. It is possible, though rare, to find an adult walking on the ground, on the roads. The easiest way to locate them is to search for the flying adults after sunset and following heavy rain, using a flashlight, and catch them with an entomological net. Light night traps can be helpful, as it is sometimes possible to see a few beetles landing on the white sheets typically used for observing Lepidoptera species. If the openings of the galleries dug by adults in the soil are found, it is possible to attempt excavating them from their burrows using a spade or a shovel. The main threat to this species is habitat conversion, as it is highly dependent on natural, original vegetation and very sensitive to habitat degradation. The overgrowth of invasive plant species such as Robinia pseudoacacia L., Amorpha fruticosa L., and Ailanthus altissima (Mill.), along with the removal of the native shrubs (Crataegus, Rosa, Prunus, and Corylus) and trees, overgrazing, burning vegetation, and using pesticides, also pose serious threats. Concrete lighting poles along roadsides can act as light traps. Saproxylic Coleoptera are becoming increasingly popular among beetle collectors and the rarity of B. unicornis significantly increases its market value. A pair of B. unicornis can be found on eBay for around USD 200.

B. unicornis is a species listed in Annexes II and IV of the EU Habitats Directive (Natura 2000) [3]. It is present in Annex II of the Bern Convention [4] and in Annex I of Resolution 6 (1998) of the Bern Convention (revised in 2011) [5]. In the Red List of Invertebrates of Romania, it has CR status [35] and is listed in Annexes 3 and 4A of EGO 57/2007 [6].

3.13. Osmoderma eremita (Scopoli, 1763) (Species Code 1084) (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae) (Hermit Beetle) (Sensu Lato)

O. eremita sensu lato was separated into more species, in Romania being present as O. barnabita Motschulsky sensu stricto (Figure 3f,g) [81,82,83,84,85]. This clarification took place after the Natura 2000 annexes were designed, the custom being to protect it as in the case of O. eremita, as both species are almost similar in rarity, environmental requirements, biology, ecology, morphology, etc., so we merged the data for the two species for Romania. O. eremita is a stenotopic, obligate saproxylic (saproxylophagous) species, with a very narrow habitat niche, the decaying heartwood of veteran, hallow trees [20,39,40,81]. It is a polyphagous species with a wide range of tree hosts, including Quercus, Fagus, Betula, Acer, Tilia, Carpinus, Populus, Ulmus, Alnus, Fraxinus, Castanea, Salix, Platanus, Morus, Juglans, Malus, Prunus, Pyrus, even Abies, Pinus, Taxus, Robinia, and Lonicera, but with possible local preference for certain tree species [86]. Adults can be active both during the day and in the night and can be seen on the bark of the tree host. Dispersal distance in flight ranges from 200 to 1500 (occasionally up to 2500) m, with 15–80% of the adults leaving the natal host tree. However, some individuals can spend their entire life, including the adult stage, inside the natal hollow tree [81]. Under optimal conditions, larval development takes two years, and up to four in an unfavourable environment. Larvae (Figure 3g) develop in large standing hollow trees, alive or dead, with the cavities rich in moist wood mould, feeding on decaying wood and its mixture of rot-causing fungi. A full-grown third instar larva, at the end of the second or third summer, clumps wood debris with salivary and faecal secretions, creating an oval-shaped cocoon for overwintering. In spring, they pupate, and in summer became adults that emerge from June (depending on temperature, even from April or May) to August, with adults being visible until September. The lifespan of adults is around one month in nature, but some females may hibernate. Males emit a strong odour, a sexual pheromone, which attracts females. Adults prefer to feed on various fruits but also on sap flows and flowers. O. eremita prefers hollow trees from the edge of the forests and clearings, being considered an ecotonal species [81]. In the absence of old forests with veteran trees, it can survive in substitute habitats with large trees in anthropogenic environments, such as urban parks, old orchards, wooded grasslands, and large trees along country roads. O. eremita is an endemic species to Europe: O. eremita sensu stricto in western Europe and O. barnabita sensu stricto in the eastern part, found from the sea level up to 2000 m [84,85,86]. Despite such a large range, their specific habitat is very fragmented, scattered, and declining across Europe, with an estimated area of occupancy of around 2000 km2 [81]. It is a rare species in Romania, found mainly in the oak and beech forests with large hollow veteran trees [20,35]. It is very rare in extra-Carpathian Moldova, and to our knowledge found in just a few forests, such as Pătrăuţi forest (ROSCI0075) and Dealul Mare–Hârlău Forest (ROSCI0076). In Bârnova Forest, the hermit beetle is not easy to spot during a normal excursion, due to its very association with the favourable large veteran, hollow trees. Therefore, if we actively search for these trees, we have the possibility to find hermit beetles. Remains of O. eremita can be found in the wood mould inside tree cavities. Non-expert observers may confuse these remains with the ones from Gnorimus variabilis (Linnaeus), a smaller species present in the site, which has smaller and more slender parts of the body, fore tibiae with two teeth, and elytra usually with whitish spots on the dorsal surface. As a non-time-consuming and non-invasive method for finding the larvae and the remains of O. eremita inside hollow trees, specially trained dogs can be used [87]. This method is also suitable for detecting other saproxylic species. The main threats are deforestation and the removal of the standing, large, veteran hollow trees. A major problem is the very slow regeneration of suitable habitats, as hollow veteran trees take decades to hundreds of years to develop into the very specific trophic niche for the saproxylophagous species like O. eremita and ecologically allied species. The destruction of just one large veteran hollow tree is an irrecuperable loss comparable to a human lifetime. Oak trees need at least 150 years to become a hollow. The disappearance of the tree host results in habitat fragmentation, which, combined with the low dispersal ability of adults, leads to a metapopulation structure limited to small areas [88]. Being a big, rare beetle species, the collection of specimens might pose a threat. The price of one exemplar of O. eremita and O. barnabita is around USD 30 on eBay, USD 60 a pair. Using pesticides can be a threat, especially for the adults.

O. eremita is a species listed in Annexes II and IV of the EU Habitats Directive (Natura 2000) [3]. It has NT status in the global IUCN Red List of Threatened Species [85], which has NT status also for O. barnabita [84], NT in the European Red List of Saproxylic Beetles [12,14], and EN in the Carpathian List of Endangered Species [62]. It is present in Annex II of the Bern Convention [4] and in Annex I of Resolution 6 (1998) of the Bern Convention (revised in 2011) [5], and is listed in Annexes 3 and 4A of EGO 57/2007 [6]. In the Red List of Invertebrates of Romania, O. barnabita has VU status [35]. O. eremita (or O. barnabita) is not listed in the Standard Data Form (SDF) Natura 2000 for ROSCI0135 [89].

3.14. Parnassius mnemosyne (Linnaeus, 1758) (Species Code 1056) (Clouded Apollo) (Lepidoptera: Papilionidae)

P. mnemosyne (Figure 3h–j) has a gliding, easily recognizable flight and one generation a year. After mating, females have a protective membranous shield on the ventral abdomen, called the “sphragis”, secreted by the male during mating, which prevents further matings (Figure 3h,i). It hibernates as a larva inside the white eggs, which are laid individually at the base of the host plants. The host plants are the species of Corydalis. Larvae can be seen in nature from March to June. Pupation occurs from April to July, inside a white silk cocoon woven on the leaves from the soil, in the litter. Adults fly from May to July and prefer red, violet, blue, and purple flowers as a source of nectar. P. mnemosyne is a meso-hygrophilous species, preferring habitats such as moist broad-leaved deciduous forests, forest meadows, alpine and subalpine grasslands, mesophile and humid grasslands, forest margins, and clearings with Corydalis spp. It is a Central Asian European species that has declined by up to 30% across Europe [90,91,92,93,94]. In Romania, it is a species found throughout the country, in meadows where host plants (Corydalis spp.) are present, from the lowlands at a 30 m altitude, to the alpine regions, up to a 2000 m altitude [20,93,94,95]. P. mnemosyne can be seen in Bârnova Forest in the specific habitats with Corydalis spp., with the main threats being habitat destruction, afforestation, and overgrazing. It is a large, beautiful butterfly, so the collection of specimens might also pose a threat. The price of one exemplar of P. mnemosyne is around USD 10 on eBay. Adults can be killed on the roads and the use of pesticides can also be a threat.

P. mnemosyne is a species listed in Annex IV of the EU Habitats Directive (Natura 2000) [3]. It has LC status in the global IUCN Red List of Threatened Species [90], LC in the IUCN Europe Red List of Threatened Species [92], and LC in the IUCN Mediterranean Red List of Threatened Species [91]. In the European Red List of Butterflies [96], it has the status NT in the IUCN Red List Category (Europe) and VU in the IUCN Red List Criteria (EU 27). It is present in Annex II of the Bern Convention [4] and is listed in Annex 4A of EGO 57/2007 [6]. P. mnemosyne is not listed in the Standard Data Form (SDF) Natura 2000 for ROSCI0135 [89].

3.15. Zerynthia polyxena (Denis & Schiffermüller, 1775) (Species Code 1053) (Southern Festoon) (Lepidoptera: Papilionidae)

Z. polyxena (Figure 4a,b) is a gorgeous, very charismatic, diurnal butterfly. A relatively similar species, Z. cerisy (Godart) is known in Romania just from a few small populations in the southeast and southwest parts of the country [93]. The red spots from the wings may serve as aposematic signals, warning the potential predators that the butterfly is toxic and not good to eat. The toxic substances (aristolochic acid) from the host plants, Aristolochia spp., are transferred to the caterpillars and adults, making them inedible. Their flight is direct and gliding, without sudden, wide, powerful movements. It has one generation a year and hibernates as a pupa, attached to stem plants by a white silk cord. Adults typically fly in the morning and afternoon, from April to early June, with a short lifespan of no more than three weeks. They prefer nectar from flowers of Geranium, Medicago, and Lathyrus, usually found near their host plants. Eggs are white and laid individually or in groups, from May to June, on the underside of the leaves, as well as on the flowers and stems of the host plants, Aristolochia spp. Larvae can be seen on the plant host in May and June. Young larvae are black, and feed on the flowers, helping in pollination, and on the young shoots. The next instars are white and show more yellow to orange on the tubercules (Figure 4c,d). The full-grown larva has an outstanding appearance, and is very easy to be seen against the green of the host plants. If the larva feels threatened, it can evert a yellow osmeterium from the prothorax (Figure 4e), which serves to repel potential predators by emitting a disagreeable odour. It pupates after four weeks.

Figure 4.

(a) Zerynthia polyxena ♀ dorsal; (b) Zerynthia polyxena ♂ ventral; (c) Zerynthia polyxena, young larvae; (d) Zerynthia polyxena, full-grown larva; (e) Zerynthia polyxena, osmeterium; (f) Euphydrias maturna ♂ dorsal; (g) Euphydrias maturna ♀ dorsal; (h) Euphydrias maturna ♂ ventral; (i) Euphydrias maturna, larva; (j) Lycaena dispar ♂ dorsal; (k) Lycaena dispar ♀ dorsal; (l) Lycaena dispar ♀ ventral; (m) Euplagia quadripunctaria dorsal; (n) Euplagia quadripunctaria ventral.

Habitats of Z. polyxena are those where the host plants, Aristolochia spp., are found, including humid and mesophile grasslands, margins of agricultural crops, roadsides, areas near watercourses, forest edges, old vineyards, along the railroads, damp areas, and ruderal zones near villages. Z. polyxena is a Ponto-Mediterranean species, distributed from southern Europe (France, Italy, and Sicily) through Central Europe (Austria and Hungary) and eastern Europe (Balkans, Greece, Romania, and Ukraine) to northwest Turkey, the southern Urals, and northwest Kazakhstan [97,98].

The area of occupancy is approximately 10,000 km2 in the EU 27 region, ranging from sea level up to a 1700 m altitude, limited to zones with favourable habitats. Population declines have been observed in many countries [93,94,97,98]. In Romania, it is widespread, from Dobrogea to submontane areas up to a 1200 m altitude, occurring in relative isolated populations. It is quite common in areas where the host plant species is present: Aristolochia clematitis L. in the lowlands, and Aristolochia lutea Desf. in the mountain regions [20,93,94,95]. Finding Z. polyxena in Bârnova Forest is closely linked to finding the host plant, A. clematitis, which grows in compact clumps, especially in the open, marginal areas of the forest. The disappearance of these ecotonal zones is the main threat, along with afforestation and the use of pesticides in nearby agricultural areas. An area of a few meters wide should be left between the agricultural lands and the forest edge. Adults typically fly from April to June, but due to climate change in recent years, adults and larvae have been observed together in July. Z. polyxena is an attractive butterfly, so the collection of specimens might pose a threat. The price of one exemplar of Z. polyxena is around USD 10 on eBay. Adults can be killed on the roads.

Z. polyxena is a species listed in Annex IV of the EU Habitats Directive (Natura 2000) [3]. It has LC status in the IUCN Europe Red List of Threatened Species [97], LC in the IUCN Mediterranean Red List of Threatened Species [99], NT in the European Red List of Butterflies [97], and EN in the Draft Red List of Butterflies (Lepidoptera: Papilionoidea) of the Carpathian Mountains [99]. It is present in Annex II of the Bern Convention [4] and is listed in Annex 4A of EGO 57/2007 [6]. Z. polyxena is not listed in the Standard Data Form (SDF) Natura 2000 for ROSCI0135 [89].

3.16. Euphydryas maturna (Linnaeus, 1758) (Species Code 1052) (Scarce Fritillary) (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae)

E. maturna (Figure 4f–h) is univoltine, with adults flying in May to the first part of July. Their flight is slow and gliding, but can become rapid when disturbed. Males can be seen sited on the bushes and lower branches of trees at forest edges, exhibiting territorial behaviour, and engaging in short chases against other butterflies. Adults prefer nectar from flowers of Veronica, Scabiosa, Plantago, Viburnum, Ligustrum, Geranium, Crepis, Ranunculus, Succisa, Salix, and Populus. Eggs are red and laid from May to July, in clusters, in several layers thick, on the underside of leaves of Fraxinus excelsior L., at a height of 4–10 m from the ground. Young larvae appear in June and are initially gregarious, building a collective shelter from silk and leaves up to a few meters above the ground. They feed together on the leaves of the Fraxinus trees. An interesting case occurs in the Natura 2000 area “Dolina Biebrzy” in Poland, where females laid the eggs not only on the leaves of F. excelsior but also on Veronica longifolia L., which serves as food for the larvae before hibernation [100]. Occasionally, the eggs can be laid on Viburnum opulus L. and Ligustrum. In Finland, Melampyrum pratense L. and M. sylvaticum L. are used both for laying the eggs and as food for larvae before hibernation [100]. Larvae hibernate after their second, third, or fourth moults, usually in the nest, which falls on the forest floor, in the litter, or in the moss on the ground. Some larvae can hibernate twice, and even a third hibernation is possible. This can help them survive during unfavourable years. In the spring, usually in March–April, larvae become active and feed on seedlings or young shoots of the initial food plants, primarily on Lonicera. After the final moult, they became polyphagous, feeding on the leaves of various plants such as Ligustrum, Populus, Salix, Lonicera, Populus, Rhinantus, Veronica, Plantago, and Valeriana. Larvae (Figure 4i) can extract iridoids and iridoid-glycosides from their plant host, which are used for self-defence and protection of larvae, pupae, and adults. The sixth, final instar larvae pupate in the low vegetation between April and June. Pupae are usually attached by a cremaster (a silk thread) on the stems of plants. Favourable habitats include broad-leaved mixed deciduous forests with Fraxinus, mixed woodland, mesophile and humid grasslands, alluvial and wet forests and shrubs, hedges, forest edges, open forests, small forests, clearings, sunny and humid standing ash trees, flower-rich meadows, and unmown meadows with nectar plants [20,35,93,94,100,101]. E. maturna is a Euro-Siberian species, with distribution from central France to the southeast of Sweden, southern Finland, the Baltic States, southeast Germany (absent in Switzerland), northern Austria, Hungary, the northern Balkan peninsula, northern Greece, extending eastward to the Urals, southern Siberia, Yakutia, Kazakhstan, northwest China, and southern Mongolia. The area of occupancy is approximately 7500 km2 in the EU 27 region, ranging from sea level up to a 900 m altitude. The species has experienced an occupancy decline of over 30% in the last 10 years, is extinct in Belgium and Luxembourg, and shows a strong decline of population size in several countries [93,94,101]. In Romania, it can be found throughout the country, except in the Danube Delta and mountainous areas above 900 m altitude. It is more frequent in Banat, Crişana, Transylvania, northern Moldavia, southern Muntenia, and Dobrogea [20,35,93,94,95]. E. maturna can be found in Bârnova Forest wherever favourable habitats occur, mainly on the forest edges, clearings, grasslands, and flower-rich meadows, as well as on the vegetation along the roadsides and the railroad that passes through the forest. Main threats include afforestation of forest clearings, loss of flower-rich grasslands, habitat fragmentation, selective extraction of ash trees, drainage of damp areas, destruction of riverside forests, mowing of roadside and railroad vegetation, stationary big cars like logging equipment on the roadside vegetation, local overgrazing, burning of vegetation, collecting of larval webbings, and ash dieback (Hymenoscyphus fraxineus arrived in Romania after 2005 and spread throughout the Moldavian Plateau between 2007 and 2013). The collection of specimens might pose a threat. E. maturna is not a particularly charismatic butterfly, resembling other nymphalids, but perhaps due to its rarity, the price of one exemplar of E. maturna is around USD 10 on eBay, similar to other Euphydryas species. Adults can be killed on the roads and the use of pesticides also poses a threat.

E. maturna is a species listed in Annexes II and IV of the EU Habitats Directive (Natura 2000) [3]. It has DD status in the global IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, LC in the IUCN Europe Red List of Threatened Species [101], EN in the Draft Red List of Butterflies (Lepidoptera: Papilionoidea) of the Carpathian Mountains [99], and NT in the Red List of Invertebrates of Romania [35]. In the European Red List of Butterflies [96], it has the status VU in the IUCN Red List Category (Europe) and LC in the IUCN Red List Criteria (EU 27). It is present in Annex II of the Bern Convention [4] and in Annex I of Resolution 6 (1998) of the Bern Convention (revised in 2011) [5], and is listed in Annexes 3 and 4A of EGO 57/2007 [6].

3.17. Lycaena dispar (Haworth, 1802) (Species Code 1060) (Large Copper) (Lepidoptera: Lycaeniddae)

L. dispar (Figure 4j–l) is bivoltine in Romania, but it can be univoltine in the northern parts of its range, such as northern Poland, and may have three generations in the southern regions. From a distance, males can be confused with those of L. virgaureae (Linnaeus) (Scarce Copper), but they can be distinguished by the prominent black elongated discal spots on the upper side of the wings in L. dispar, and by the brown underside of the posterior wings with submarginal white spots in L. virgaureae. The adults of the first generation fly from May to June, while those of the second generation appear from July to early September. The second-generation individuals are usually smaller and more numerous. Especially on sunny days, males can be recognized from a distance by their bright coloration and fast flight. They exhibit territorial behaviour, flying in short races against other males and butterflies while actively searching for females. Females tend to stay more grounded on the plants, and spotting them usually requires an active search. Adults use various flowers as nectar sources, such as those of Cirsium, Achillea, Taraxacum, Ranunculus, Trifolium, Arctium, etc. A single female can lay up to 500 white eggs, either individually or in small groups, on the upper side of the leaves, near to the midrib, on various species of Rumex, such as R. aquaticus L., R. crispus L., R. hydrolapathum Huds., R. obtusifolius L., etc. The larvae initially feed on the underside of the leaf, and later consume the entire leaf. The larvae of the second generation overwinter at the base of the host plants’ leaves, in the second or third instar, during which they change colour to brown-violet. They became mature the following year in April–May, and then pupate. Pupae are usually attached to leaves or plant stems by a white silk cord. L. dispar is a hygrophilous species, with favourable habitats including wetlands, humid grasslands, water-fringe vegetation, mesophile grasslands, blanket bogs, fens, lakesides, edges of streams, flood areas, moorlands, montane grasslands, marshy habitats, riparian areas, and any similar habitats where the foodplants, Rumex spp., are present [93,94,102,103]. L. dispar is a Palearctic Euro-Siberian species with a distribution range extending from France, across the entirety of Europe, in the north to the south of Finland to north Turkey. It is also found in temperate regions of Asia, China, usually from sea level up to around a 600–1000 m altitude. In EU27, the area of occupancy for L. dispar is around 30.000 km2, with a population decline exceeding 34% across Europe and the EU 27 over the past 10 years [93,94,102]. In Romania, it can be found throughout the entire country, including mountain areas up to 1200 m in altitude [20,35,93,94,95]. In Bârnova Forest, it is strongly dependent on humid habitats and the presence of its caterpillar host plants, Rumex spp. Wherever Rumex and wet areas occur, there is a good chance of seeing them, especially the flying males. The main threat is the destruction of its humid habitats caused by land drainage and the invasion of shrubs and trees. Other risks are overgrazing, afforestation of humid areas, burning of vegetation, loss of flower-rich humid grasslands, habitat fragmentation, and mowing of mesophile vegetation. Climate change, with prolonged periods of droughts, poses a serious threat in Bârnova Forest, especially when combined with wood harvesting, leading to the desiccation of wet areas and significant alteration of the specific habitat. The collection of specimens might pose a threat. L. dispar, especially the males, are a strikingly beautiful butterfly; the price of one exemplar is around USD 10 on eBay, similar to other Lycaena species. Adults are also vulnerable to being killed on roads, and pesticide use presents an additional risk.

L. dispar is a species listed in Annexes II and IV of the EU Habitats Directive (Natura 2000) [3]. It has NT status in the global IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, LC in the IUCN Europe Red List of Threatened Species [104], LC in the European Red List of Butterflies [96], and LC In the Red List of Invertebrates of Romania [35]. It is present in Annex II of the Bern Convention [4] and in Annex I of Resolution 6 (1998) of the Bern Convention (revised in 2011) [5], and is listed in Annexes 3 and 4A of EGO 57/2007 [6].

3.18. Euplagia (Callimorpha) quadripunctaria (Poda, 1761) (Species Code 1078) (Jersey Tiger, Spanish Flag) (Lepidoptera: Erebidae)

E. quadripunctaria (Figure 4m,n) fly from the second part of June to the first part of September. Although it is a nocturnal butterfly, it is very active during the daylight, feeding with its long orange proboscis on Eupatorium cannabinum L., as well as the nectar of many other flowers. If disturbed, they raise their front wings, revealing their contrasting red-orange hindwings. Eggs are white and laid individually or in groups on the upper side of the leaves of various host plants. It overwinters as a young larva, hidden among the leaves’ litter on the ground, becoming active again in the following spring. Larvae are polyphagous, feeding on the leaves of Rubus, Urtica, Lamium, Corylus, Cytisus, Epilobium, Lonicera, Echium, Lithospermum, Sarothamnus, Taraxacum, Glechoma, Senecio, Plantago, Borago, Lactuca, etc. Pupae are usually found between leaves, in the litter, in June–July. Favourable habitats include riparian and herbaceous areas, wet meadows, forest edges and clearings, open sunny habitats near the water courses with Eupatorium, damp scrublands, and vegetation along forest roadsides [20,105,106]. E. quadripunctaria is a Palearctic species, with a distribution area range extending from Great Britain and Spain across most of Europe, excluding the extreme northern regions, to southern Urals, Asia Minor, Caucasus, southern Turkmenistan, and Iran. It is widespread throughout Romania, occurring up to altitudes of 1200 m, wherever favourable habitats are present [20,107]. In Bârnova Forest, it is a relative common species in favourable habitats such as vegetation on the sides of the forest roads and railroad, forest edges, clearings, riparian herbaceous areas, and open sunny habitats near water bodies. Main threats include the destruction of these habitats, afforestation, destruction of pupae and hibernating larvae during the logging operations, habitat fragmentation, drainage of damp areas, mowing roadside and railroad vegetation, stationary big cars like logging equipment on the roadside vegetation, local overgrazing, and burning of vegetation. In the evening and in the night, this species is attracted to light sources, such as the concrete lighting poles along the sides of the roads, which act as light traps. Climate change with long periods of droughts can be a serious problem also in Bârnova Forest, along with wood harvesting. The result is the desiccation of wet areas and alteration of the specific habitat. The adults can be killed on the roads and the use of pesticides can also pose a threat. The collection of specimens may be a further risk, as the price of one individual is around USD 10–15, and USD 30 for a pair on eBay.

E. quadripunctaria is a species listed in Annex II of the EU Habitats Directive (Natura 2000) [3]. It is present in Annex I of Resolution 6 (1998) of the Bern Convention (revised in 2011) [5] and is listed in Annex 3 of EGO 57/2007 [6].

4. Discussions

Not all the Natura 2000 sites overlap with the biodiversity hotspots for arthropods [13], but luckily, in Bârnova Forest, there is a strong corelation between the established Natura 2000 site and the presence of the invertebrates of community importance.