Abstract

In the quest for effective environmental governance, the integration of legal and cultural pluralism within conservation strategies emerges as a critical factor, especially in regions marked by rich ethnic diversity and complex historical legacies. This paper explores the symbiotic relationship between state conservation efforts and the engagement of local communities, with a particular focus on the Indigenous Maroon communities in the Blue and John Crow Mountains (BJCMs) of Jamaica. It underscores the imperative of aligning conservation objectives with the aspirations and traditional practices of these communities to foster sustainable ecosystems and safeguard Indigenous autonomy. Central to this discourse is the development of collaborative frameworks that respect and incorporate the legal and cultural dimensions of pluralism, thereby facilitating a co-managed approach to environmental stewardship. This study emphasizes the role of collaboration and trust as pivotal elements in cultivating a mutual understanding of the interdependencies between state law and Indigenous law. This research advocates for a reciprocal exchange of knowledge between the state and community members, aiming to empower the latter with the resources necessary for effective environmental protection while respecting their legal autonomy. This approach not only enhances conservation initiatives overall, but also ensures that these efforts are informed by the rich cultural heritage and traditional ecological knowledge of the Maroon communities. By examining the conservation practices and governance challenges faced by the Maroons in the BJCMs, this paper reveals the nuanced dynamics of implementing state-led conservation laws in areas characterized by cultural and legal pluralism. The findings highlight the necessity for state regulatory frameworks to enable collaborative governance models that complement, rather than undermine, the traditional governance structures of the Maroons. This research contributes to the broader discourse on environmental governance by illustrating the potential of culturally informed conservation strategies to address environmental threats while respecting and reinforcing the social fabric of Indigenous communities.

1. Introduction

1.1. Legal and Cultural Pluralism in Jamaica

The Caribbean region is pluralistic from both cultural and legal perspectives due to the characteristics of colonizers, as contrasted with the enslaved and indentured servants that they brought with them Becker, 2015 (136–164) [1]. While the Caribbean’s cultural pluralism is typically celebrated from a travel and tourism standpoint, the legal pluralism evidenced by various forms of Indigenous and Afro-centric laws has been approached cautiously by Caribbean states as well as scholars [1] Becker, 2015 (136–164). This is because of the complexities arising from legal and cultural pluralism, under which both the state and local peoples have legitimate claims to the governance of natural resource management, which stand alongside cultural pluralism, and which constitute a legacy of the cultural conflict of the historical plantation.

Within this Caribbean context, we define environmental governance as the multifaceted processes and institutions through which societies manage and mitigate impacts on the environment [2] (Fonseca et al., 2022). This governance framework engages both formal and informal actors and utilizes a variety of rules and procedures that directly influence interactions between humans and the environment. In legally and culturally pluralistic societies, ethnic differences in resource management practices may or may not map neatly on to the informal and formal rules intended to guide those practices. Formal rules refer to codified regulations and laws that are officially enacted and enforced by the state. These include statutory laws, regulations, and policies that dictate specific requirements and standards for environmental management [3] (North, 1990). Informal rules, on the other hand, encompass the customary practices, traditional norms, and unwritten codes of conduct developed and followed by local communities over time. These informal rules are often rooted in historical and cultural contexts and govern the day-to-day interactions and resource management strategies within these communities [4] (Ostrom, 1990).

Within culturally and legally plural societies, the principle of inclusivity is central for effective environmental governance, and this demands that the perspectives and traditional knowledge of diverse groups, especially marginalized and Indigenous communities, are incorporated in decision-making processes [5] (Baud et al., 2011, pp. 79–88). Additionally, such pluralism necessitates governance approaches that are sufficiently flexible to accommodate and reconcile differing legal norms and cultural practices related to environmental management. This adaptability must be a cornerstone for laws and practices to respond dynamically to changing environmental conditions and internal dynamics, which is crucial in managing the complex interactions between different governance systems in pluralistic societies.

The tools for implementing environmental governance are equally varied, encompassing both regulatory measures such as legislation, which clearly define state environmental rights and responsibilities, and market-based instruments like taxes and permits, designed to achieve specific environmental objectives (Tamanaha 2000) [6]. These tools are typically complemented by voluntary agreements and informational strategies that encourage stakeholders to reduce environmental impacts and modify behavior through educational outreach and data sharing. In culturally and legally pluralistic societies, these tools must be deployed with sensitivity to the diverse legal contexts and cultural practices, ensuring that environmental governance not only addresses ecological challenges but also respects and reinforces the cultural and legal diversity that defines these communities (Delville, 1999) [7].

As evidenced by this case study, challenges related to the enforcement of state environmental regulatory law in legally and culturally pluralist societies may also be particularly fraught due to tensions stemming from differences between the state and local peoples that are grounded in the legacy of colonialism. On the one hand, the state may adopt codified rules to govern resource management that are then imposed in a neo-colonial fashion on local peoples. This often occurs without the recognition of their histories, knowledge, and experiences, or the context-specific characteristics of local resources. In this regard, it is crucial for states to recognize local cultures and customary rules governing resource management (Fitzpatrick 2005) [8]. On the other hand, local peoples may experience changes from historical conditions that can modify the impacts of customary resource management practices on local resources, potentially threatening cultural sustainability and ecosystem integrity. In that regard, it may also be the case that local peoples would benefit from engaging with the state to improve environmental governance, albeit in a decolonized mode of co-equal collaboration.

Accordingly, this study examines the implications of cultural and legal pluralism for environmental governance in the Blue and John Crow Mountains (BJCMs) of Jamaica. Home to the Indigenous Maroons, the BJCMs are an IUCN Category II protected area and a UNESCO World Heritage Site, so designated because of its ecological as well as cultural significance. While the Maroons have a long history of autonomy in their customary practices of natural resource management, they now exhibit changes that reflect challenges which may undermine the sustainability of those practices. Meanwhile, the Jamaican state presents complications in how it engages with Maroons due to the history of colonialism in Jamaica. We analyze the roles of cultural and legal pluralism, along with other factors, as they influence Maroon environmental governance in the BJCMs. The findings reveal multiple challenges to customary resource management practices among the Maroons. The findings bear implications for legal and cultural pluralism as related to environmental governance, notably in contexts characterized by historical colonialism. We conclude by offering recommendations for collaborative environmental governance among states and legally autonomous communities.

1.2. Theoretical and Scholarly Perspectives on Legal and Cultural Pluralism

Legal and cultural pluralism provide orienting analytical concepts by which to understand cases where state law encounters non-state governance systems. In the words of Griffiths (1986) [9], “not all law is state law nor administered by a single set of state legal institutions”. Accordingly, one of the central tenets of legal and cultural pluralism is that various normative orders co-exist in a society and often construct alternative models of governance (Kleinhans and Macdonald, 1997) [10]. The literature on legal pluralism typically distinguishes between three forms of pluralistic legal arrangements. First, legal pluralism may be used to refer to circumstances in which there is an official recognition of a body of norms as law, though it is not considered to be applicable in a particular jurisdiction—as in the case of international or foreign law (Merry 2013) [11]. As noted by Twining (2010) [12], such cases of legal pluralism involve overlapping state and non-state regulations. In the second instance, the state incorporates traditional or Indigenous norms into its own legal system as formal legal rules (Gover, 2008) [13]. In this case, local customary rules become state law. Third, legal pluralism can refer to official deference to a distinct legal system that locally produces and implements its own law (Gover 2008) [13]. In this case, there are two parallel systems of rules for governance. This describes the case of the Maroons.

The Maroons further evidence the importance of cultural pluralism in environmental governance, particularly as is aptly put by Bilby (2005) [14], who describes this concept as divergent cultural practices in the context of domination. The challenge here is that scholars have argued that legal pluralism can appear to challenge elements of the principle of the “rule of law”, which maintains that law should be comprehensive, coherent, transparent, and predictable (Gover 2008) [13]. Under the rule of law, the law should be applicable to all citizens in the same way. However, cultural pluralists argue that attempts to maintain a single unitary legal code may undermine rather than support the legitimacy of the state (Pimentel 2010) [15]. This is because culturally pluralist societies in the Caribbean are not simply loosely connected groups, but rather groups within a society that are arranged in terms of a hierarchy of privilege. The antimony created by legal and cultural pluralism in relation to environmental regulation is such that, while the environmental goals of multiple groups in a society are the often same, pluralism occurs in the context of conflict and cultural opposition, which often result from the oppression of subaltern groups by the elite (Shah, 2005) [16]. Legal pluralists therefore assert that by acknowledging and respecting the legal orders of non-state groups, the state is legitimized for being fair by demonstrating restraint in the exercise of its authority. Arguments that favor customary laws and local rule over state law in governing natural resources emphasize that Indigenous laws tend to account for long-term conservation over generations in a community, in contrast to the short-term goals that typically motivate state regulation and enforcement (Vaughan, Thompson, and Ayers 2017) [17].

While these considerations enrich legal and cultural pluralism, they often fail to adequately account for the conflicting perspectives between Indigenous and state institutions. Such expectations often underestimate or ignore the complexities and challenges that may arise from the state due to its lack of capacity to follow through on agreements (Forsyth, 2008) [18]. In addition, cultural pluralism highlights complications that may arise from cultural differences and distrust among stakeholders (Ostrom, 2010) [19]. In particular, relationships among states and communities can pose challenges during the design of the governance process. In most cases, control typically resides with the state, though the extent of power sharing varies among cases (Green and Lund 2015; Akbulut and Soylu 2012) [20,21]. Notably, in societies with ongoing conflicts regarding property rights, land ownership, and environmental governance, states may repress customary authorities and local rule.

With regard to cultural pluralism, of key concern are the legacies of neocolonialism, which impact the autonomy of many Caribbean societies today. This is perhaps best explained in terms of the concept of majoritarianism, defined as “the assumption that the will of the [elite] majority is absolute and is the final authority when defining the limits of individual rights and freedom” (Becker, 2015 p. 139) [1]. Majoritarianism is less problematic in legally homogeneous societies. This includes the case of countries that engage in the colonization of other territories. However, colonized countries often exhibit histories with cultural pluralism due to the imposition of cultural belief systems of foreign colonizers on local peoples. Even where ethnic majorities may have established cultural traditions of local rule, official legal systems often derive from colonial authorities that promulgated oppressive legal codes.

Despite the current vibrant discourse on conservation efforts, there is surprisingly little systematic empirical research to assess the impact of legal and cultural pluralism on environmental governance in the Caribbean. As a result, policy analysts and policy makers lack evidentiary support to guide the design of environmental laws in their legally diverse societies, and there are relatively few data about inclusive and appropriate strategies for meeting environmental objectives. Previous research on legal and cultural pluralism tends to be legalistic in its approach and often reflects a hegemonic western perspective (Bohannan 1965) [22] and (Twining, 2010) [12]. Therefore, previous work offers limited insights for understanding the unique challenges that are often experienced by Caribbean countries that are former colonies seeking to balance more than one legal and cultural system. This study addresses some of these limitations by focusing on cultural pluralism, as reflected in legal pluralism, due to the presence of autonomy in an Indigenous community. Such work contributes to the literature by highlighting issues or challenges that may arise in similar cases of parallel environmental governance.

1.3. Historical Background: Jamaica and the Maroons

Jamaica provides a useful case study for examining contemporary legal and cultural pluralism within the historical context of colonialism. During Jamaica’s colonial period, Europeans aggressively brought land under their control and subjugated Indigenous peoples, a pattern evident throughout the Caribbean (Starr and Collier 1989) [23]. By the 19th century, European colonization had led to the near extinction of Indigenous groups, including the Tainos Indians. Central to European colonization in the Caribbean was the plantation system, which relied on slave labor imposed by force on Africans (Diver 2016) [24]. During this period, Jamaica became the vanguard of agricultural capitalism in the British West Indies (Besson, 2016) [25]. However, enslaved Africans in the Caribbean resisted European domination, particularly in Jamaica, where they engaged in slave rebellions (Besson, 2016) [25]. Marronage, the practice of escaping slavery and establishing autonomous Maroon communities, became commonplace on the island. Escaped slaves often joined Indigenous Tainos who had fled to the mountains during colonization, forming unique communities. Genealogical examinations have confirmed that the matriarchal DNA of Maroons reflects both African and Indigenous Tainos Indian lineages (Madrilejo, Lombard, and Torres, 2015) [26], and accordingly, Maroons self-identify as Indigenous. Maroon communities were established in less accessible areas, such as mountains, forests, and ravines, with a key region being Jamaica’s Blue and John Crow Mountains (BJCMs).

Maroon societies in the BJCMs established their own systems of rights to land and rules for natural resource management, reflecting broad Indigenous knowledge regarding the use of medicinal herbs, agricultural methods, and fishing techniques (Becker, 2015) [1]. The customary rights and regulations in Maroon societies were eventually formally recognized by European colonizers and later the Jamaican state. The land claims and use rules of the Maroons were transformed from customary rights to legal freeholds by treaties signed by the British, most notably Cudjoe’s Treaty of 1739, which granted the Maroons their freedom and legal rights, thus providing the basis for autonomous Maroon law. This situation has given rise to a form of legal pluralism characterized by the coexistence of two distinct legal systems: the colonial European legal framework and the Indigenous legal traditions of the Maroons, which have persisted since 1739. As demonstrated in Figure 1, this duality has generated, and continues to generate, significant tensions regarding legal sovereignty within Jamaica.

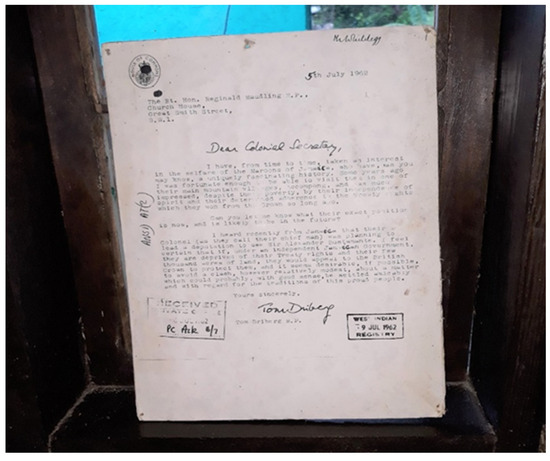

Figure 1.

Letter dated 5 July 1962 from Tom Driberg (British Minister of Parliament) to Reginald Maudling (Secretary of State for the Colonies) seeking clarification on the rights of the Maroons prior to Jamaica’s Independence on 6 August 1962. (© Jones Collection).

In post-independence Jamaica, the legitimacy of Maroon law has been tacitly acknowledged by the Jamaican state. This is the case despite the fact that the Jamaican constitution does not explicitly recognize Maroon autonomy. The informal endorsement of Maroon law lends credence to the fact that customary and Indigenous law does not rely on constitutional recognition for its validity (Forrest and Corrin 2013) [27]. However, the implicit relationship between the Maroons and the state has created a delicate situation for governance in practice. While the Maroons in Jamaica constitute a case of parallel legal pluralism, that pluralism is not entirely formalized. This obscures the complexities of the relationship between state law and Indigenous law, particularly regarding environmental governance. Following the Maroon Treaty of 1739, the Maroons were granted 1500 acres of common land. The Maroons view this treaty as a sacred charter for the use of their land. However, this land falls within the BJCM National Park, a stated-designated protected area in Jamaica. Consequently, despite previous treaties and declarations of autonomy, there is also a jurisdictional overlap in spatial terms. The jurisdictional overlap thus creates conditions for potential conflicts in terms of authority with regard to governance, including rule enforcement. As a result, disputes persist as to whether the state has jurisdiction of Maroon land under the tenets of the environmental regulatory law, which guides the BJCM National Park, and thus whether Maroon resource management practices should correspond with state regulations for environmental governance.

1.4. Jamaica’s Environmental Governance Framework

As noted in Figure 2, the BJCMs boast a multi-level system of governance, each with distinct roles and influences that shape environmental management and cultural preservation. For instance, international organizations and agreements influence Jamaica’s environmental governance framework, and therefore Jamaica’s compliance with the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) guidelines and its designation of the BJCMs as a UNESCO World Heritage Site must reflect international standards for conservation. These international designations impose specific obligations on the Jamaican state to protect the ecological and cultural values of the BJCMs, thereby influencing national and local governance practices.

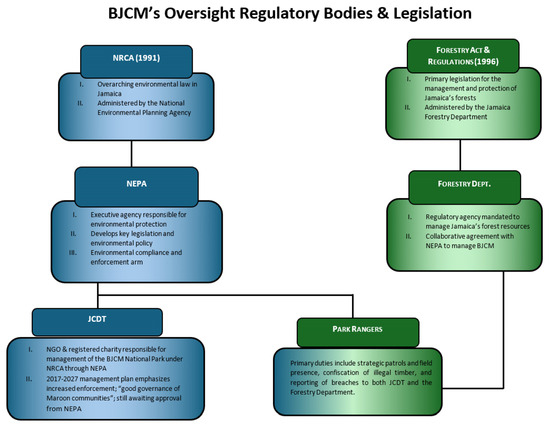

Figure 2.

State bodies with regulatory oversight of the Blue and John Crow Mountains (BJCMs).

At the national level, the Jamaican government plays a crucial role in establishing and enforcing environmental laws and policies. The Natural Resources Conservation Authority Act (NRCA) is the overarching regulation that “provides for the management, conservation and protection of the natural resources of Jamaica” (Ministry of Justice, Jamaica). The NRCA established the National Environmental Protection Agency (NEPA) as the governing body for implementation purposes, with the authority to delegate its functions to other state agencies. In the BJCMs, NEPA delegated this authority to the small and underfunded Jamaica Conservation Development Trust (JCDT), which, through 12 Park Rangers, is mandated to conduct monitoring exercises in the 64,247 acres of the BJCM National Park and its buffer zone.

At the local level, Maroon communities maintain their own governance structures, based on customary laws and practices that have been preserved since the signing of treaties with the British. These local governance systems involve traditional leadership and community-based management practices that reflect Indigenous knowledge and cultural heritage. Maroon governance in the BJCMs includes rules for land use, resource management, and cultural practices.

The interactions between these different levels of governance often challenge collaborative efforts in the BJCMs, where state regulations for environmental conservation may conflict with Maroon governance, aimed at maintaining the cultural identity. The BJCMs therefore provide an interesting context for a study of legal and cultural pluralism because it is both a state-protected area as well as Indigenous land. As a protected area of biological value, the BJCMs are sensitive to human disturbances that could cause harmful ecological impacts. But as an area of cultural importance, due to the historical presence of the Maroons, the BJCMs are also an Indigenous territory with local rules and customs, which may not neatly coexist with state regulations. Consequently, there are two sets of rules with distinct sources of authority in the BJCMs: state regulations and Maroon governance.

2. Study Area

2.1. Overview

The Leeward Maroons of the BJCMs are one of two major Maroon communities in Jamaica, the other being the Accompong Maroons in Jamaica’s Cockpit Country. The terrain of Maroon territory in the BJCM, as exhibited within the red border of Figure 3, exhibits a highly uneven topography in a zone of mountainous forests and natural pastures, with no clearly defined boundaries between Maroon and state land. The Maroons have lived in this region since before the signing of the 1739 Peace Treaties. They reside on the riverbanks, from which they hunt, fish, cultivate crops, extract timber, and gather non-timber forest products as the main sources of their traditional subsistence livelihoods. Despite maintaining their cultural values, the Maroons have recently begun to be integrated into market networks. Consequently, they have incorporated some non-traditional market-oriented activities, and, as a result, Maroon lifestyles, particularly among their youth, are undergoing rapid changes.

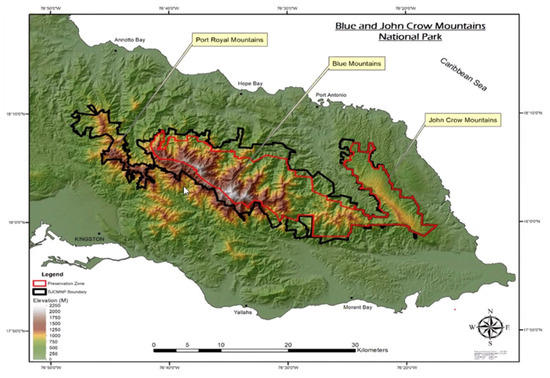

Figure 3.

Current map of the Blue and John Crow Mountains, showing the UNESCO World Heritage Site preservation zone and the BJCM National Park boundary in Black. (Source: birdscaribbean.org) (© Jones Collection).

On Maroon lands, law-making and legal practices are considered to be internal matters of the respective communities and are open only to Maroons. Among the autonomous powers of the Maroons are the authority to design their constitutions, choose their councils, and determine laws for internal governance. The right to exercise judicial power is recognized in Article 12 of the 1739 Treaty. A Maroon council is led by an elected Colonel who oversees community affairs and settles internal disputes. The Colonel holds the only post that is elected, although ironically the voting process is conducted by using the Jamaican state’s ballot apparatus. In turn, the Colonel selects council members who are collectively viewed as the repository of laws, which are handed down orally. The council is comprised of seven ministerial officers, including Ministers of Security and the Environment, each with their own portfolio.

2.2. Cultural and Legal Context

The Maroon communities exhibit a profound reverence for the spiritual domain, which significantly influences their communal governance through the prism of spiritual beliefs, as crystallized in their customary legal frameworks. For the Maroons, the concept of land transcends mere physical territory to embody a sacrosanct and religious dimension, imbued with symbolic imports. This reverence for ancestral spirits not only shapes their spiritual worldview but also plays a pivotal role in the formulation of customary laws. The genesis of these laws is deeply rooted in Myal ceremonies, during which the Colonel engages in spiritual deliberations to make critical decisions regarding environmental management practices, including arboreal conservation, land clearing for agricultural purposes, and the preservation of specific flora. These Myal ceremonies are characterized by the congregation of community members, who utilize ceremonial paraphernalia and musical instruments to facilitate communion with their ancestors. Through the employment of drums, the sacred abeng horns, and white rum, the Maroons engage in Myal practices to seek ancestral guidance, which subsequently informs their legislative processes. Although this method of rulemaking may diverge from conventional legal procedures, it encompasses the core functions of law, including regulation, enforcement, and deterrence.

The subsistence strategies of the Maroon communities are predominantly anchored in agriculture and the sustainable extraction of forest resources. Maroons articulate a communal philosophy that the commons serve both the present and future generations, notwithstanding the reality that many Maroons reside beyond these communal lands, including diasporic communities. Those who cultivate the common lands are afforded rights that persist until death, with these rights being inheritable by their progeny. The forest yields a plethora of resources, including game, fish, medicinal fruits and seeds, and commercial goods like yucca, bananas, and timber. Engagement with market economies has facilitated Maroon interactions with the broader Jamaican populace. This engagement is driven by a dual motive: the aspiration to augment income through tourism and timber sales, and the pursuit of formal legal acknowledgment and property rights for their lands and natural resources.

The foundational pillar of Maroon Indigenous jurisprudence is rooted in traditional customs, with oral histories serving as the conduit for the transmission of legal principles within Maroon society (Besson, 2016) [25]. These oral traditions not only delineate land rights and the framework for political governance, they also embody the ethos of the community’s legal and normative order. Significantly, the process of law making within Maroon communities is characterized by its inclusivity and democratic ethos, with community assemblies playing a pivotal role in the formulation and ratification of legal resolutions. This participatory approach underscores the democratic underpinnings of the Maroon legal system, where community consensus is integral to the legislative process.

Adjudication within Maroon society is conducted in communal spaces, facilitating a transparent judicial process that reinforces established norms and values. This process is notably inclusive, engaging all segments of the community—men, women, and children alike—in the judicial discourse. A distinctive feature of Maroon jurisprudence, in contrast to the formal legal system of the Jamaican state, is its adaptive and case-by-case approach to conflict resolution, eschewing a prescriptive cataloging of offenses in favor of a flexible, context-sensitive adjudication framework. This adaptability is indicative of the dynamic nature of Maroon society, challenging prevailing stereotypes of Indigenous communities as resistant to change.

3. Methodology

The methodological framework for this case study was inspired by the urgent need to understand and document the Maroons’ traditional practices and their interactions with state environmental laws against the backdrop of increasing environmental governance challenges. The examination of the interplay between diverse legal and cultural frameworks and their influence on environmental governance within the BJCMs necessitated the adoption of a qualitative, interpretive research methodology. This study critically assessed the extent to which external issues, such as state-led environmental governance measures or internal intra-group dynamics, compromised the Maroons’ capacity to sustain their legal and cultural sovereignty.

The data underpinning this research were collected through in-depth semi-structured interviews, document analyses, and personal observations conducted by the first author from April 2017 to March 2019. A total of 49 interviews were conducted with Maroons and state representatives, including those from regulatory agencies and Park Rangers (Guest et al., 2006) [28]. Interviewees were selected using a purposeful sampling strategy that prioritized their expertise and involvement in environmental law and governance within the BJCMs. All interviews were digitally recorded (when permission was granted), and subsequently transcribed verbatim by the first author. When participants did not grant permission to record, the first author recorded the conversation through notetaking. The transcribed interviews were returned to the interviewees for verification, a process known as “member checking” (Carlson, 2010) [29].

Document analysis and personal observations further enriched the dataset and facilitated triangulation with the interview data (Padgett 1998) [30]. A comprehensive collection of 53 documents relevant to the case was amassed, comprising academic, legal, and online sources. Personal observations were recorded throughout the interview process and field observation, and during two Maroon community meetings, in which issues related to environmental governance were discussed. This methodological framework enabled an in-depth exploration of the subjective perceptions and lived experiences of both Maroon community members and law enforcement personnel, facilitated by a direct, participatory relationship between the researcher and the participants. Observations were conducted in three Maroon communities within the BJCMs: the Upper Rio Grande, Charles Town, and Moore Town communities. Access to these communities was secured through established research relationships with the community leaders, or Colonels. Within these locales, structured engagements with both the Maroon council and the broader Maroon community were organized, enabling the scheduling of individual, in-depth interviews. Over a span of two years, the investigation employed an ethnographic approach, integrating both participant observations and interviews as primary methodologies for data collection. The interviews were focused on themes such as legal and cultural pluralism, environmental governance, and the roles of various stakeholders in either supporting or contesting the prevailing legal paradigms.

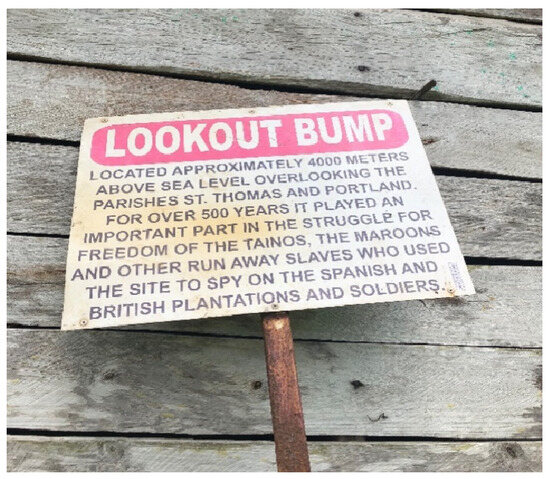

Participant observation within the Maroon communities and among Park Rangers provided invaluable insights into non-verbal communication, the intricacies of interpersonal dynamics, direct observations of governance practices and representations of Maroon territory (as evidenced in Figure 4). This immersive approach was pivotal for triangulating data and crafting a nuanced, interpretive analysis of the findings (Patton 2015) [31]. Our observations were particularly instrumental in uncovering the subtleties of Maroon governance practices and their evolving responses to environmental and intra-group challenges. These interactions with the Maroons and Park Rangers allowed us to observe and document the lived realities of environmental governance in the BJCMs, facilitating a holistic understanding of the socio-environmental dynamics at play.

Figure 4.

One of several signs reflecting Maroon land ownership in the BJCMs (© Jones Collection).

The collected data were systematically coded to uncover challenges to collaborative state–Maroon environmental governance, potential opportunities for collaborative processes, the underlying assumptions of the state regarding Maroon environmental governance, and the extent to which Maroon sovereignty and legal autonomy in environmental governance were acknowledged by the state. Open and axial coding techniques were employed using Atlas.ti version 8.3.20 computer-assisted qualitative data analysis software, guided by an initial conceptual framework that allowed for the coding of emergent themes during data analysis. These emergent themes significantly informed the practical recommendations presented in this study.

Ethical Considerations

Throughout the unfolding of this research project, ethical considerations and participant confidentiality were maintained. All participants were required to provide consent for their participation, and their identities were protected. Pseudonyms have been used to replace the participants’ names in this case study, and in the photographs provided, the faces of participants have been blurred for confidentiality, except for those individuals who explicitly signed consent forms allowing their images to be used.

4. Results

The ensuing results elucidate the practices and outcomes of environmental governance strategies within the Blue and John Crow Mountains (BJCMs) of Jamaica, focusing on the interplay between legal and cultural pluralism. This study identifies key areas of concern, including the preservation of biodiversity, the use of natural resources, and the integration of traditional Maroon governance practices with state environmental regulations. In particular, our findings detail a series of challenges between the state and the Maroons in forging collaborative efforts aimed at enhancing environmental governance in the BJCMs. These include the establishment of participatory management frameworks, the development of investigative and monitoring programs tailored to Maroon heritage and environmental stewardship, and respect for (rather than fear of) Maroon cultural practices. We delineate the natural-resource-use methods employed by the Maroons, which simultaneously integrate conservation with state-sanctioned Indigenous practices. In summary, we highlight the Maroons’ perceived illegitimacy of Jamaica’s “western” notions of conservation and the state’s unique, self-imposed restraint in providing legal assistance to the Maroon communities.

4.1. Regulations vs. Rituals in the BJCMs

In 2015, UNESCO World Heritage Site status was conferred on the BJCMs in recognition of their profound cultural heritage and ecological significance. This prestigious designation implies that the BJCMs now fall under the purview of UNESCO’s operational guidelines for the governance of protected areas, delineating the requisite institutional and regulatory frameworks essential for the preservation of this status. The global recognition afforded by this UNESCO designation has catalyzed economic benefits, notably augmenting income through enhanced tourism and the sale of coffee within the BJCM domain. Consequently, the state is impelled to safeguard this designation by implementing more stringent enforcement measures within the mountainous region. Nonetheless, despite the cognizance of the intensified enforcement initiatives ensuing from its UNESCO status, the Maroon community has articulated a prioritization of their land’s use for cultural and religious practices. The Maroons, asserting their custodial role over their territory in the BJCMs, underscore their instrumental contribution to securing the UNESCO World Heritage Site designation. They posit that prior attempts by Jamaica to attain this designation were futile until an auspicious visit by a UNESCO official to the Maroon enclave was made, during which the ancestors purportedly sanctioned the designation, thereby underscoring the symbiotic relationship between cultural stewardship and ecological preservation. As further evidence that the current legal dynamics between the Maroons and the State are rooted in a historical continuum of resistance against subjugation, “Jackie”, a Secretary of one of the BJCM Maroon communities, expressed the following regarding the UNESCO designation:

Without us they would never have won the nomination. When the lady [UNESCO representative] came here, the ancestors spoke to her and so because of us they got it. So, they [the state] know they can’t tell us what to do. We are the reason they got it, so their rules don’t apply to us.(Jackie, 8 July 2017).

This position does not, however, suggest the Maroons’ disregard for environmental stewardship. As previously elucidated, the Maroon legal framework prescribes the utilization of flora strictly in accordance with traditional dictates, necessitating explicit authorization from the Colonel and the council. The removal of plant life without such authorization incurs penalties for offending Maroons, which range from compulsory exposure to the elements for a specified duration to the obligation of replanting multiple specimens as restitution for the one extracted. This regulatory schema reflects a deep-seated reverence for ancestral spirits within the Maroon community, with a prevailing belief that the unauthorized exploitation or removal of botanical resources will invoke both physical and spiritual repercussions. During our empirical investigation, an incident was observed where a Maroon individual, in an attempt to demonstrate the medicinal virtues of a specific plant to the first author, contravened these regulations by uprooting it without prior permission, and subsequently faced censure from Jackie, the Secretary of the Maroon council, for this infraction. Such is the sacrosanctity attributed to the flora of Maroon territories that in an interaction with “Theo”, the Minister of Agriculture of the Moore Town Maroons, it was conveyed that only a subset of the medicinal applications of these plants could be disclosed to the first author, who was still considered to be an outsider to the community.

The narrative accounts from other participants regarding the intersection of their religious practices with their environmental engagements highlighted a profound interdependence. The upkeep of rivers, flora, and monuments in alignment with ancestral edicts is deemed crucial; any deviation risks the forfeiture of ancestral protection against governmental intervention, natural calamities, disease, and famine. Furthermore, adherence to these spiritual and legal mandates is imperative for sustaining the Maroons’ capacity to offer healing services to non-community members, a practice that commands a substantial remuneration. Thus, the social and judicial integrity of the Maroon community is preserved through strict adherence to the edicts governing the stewardship of their natural and cultural heritage.

Yet simultaneously, the veneration Maroons hold for plant species within their territories, while culturally significant, inadvertently exacerbates ecological vulnerabilities within the BJCMs through their cultivation of flora for ancestral veneration and medicinal applications which are invasive and thus detrimental to the region’s delicate ecological balance. Further, the Maroon practice of igniting fires during sacred ceremonies presents additional ecological and legal challenges, as these areas fall under state-protected land.

Under Sections 4, 7(4), and 13(1) of the National Park Regulations (1993) [32], cutting or destroying plants within a national park is designated as an offence. Additionally, Section 12 of the same regulations specifies that it is an offence to light, maintain, or use fire, except for domestic purposes, in designated areas (see Figure 5a,b). A senior representative of the Jamaica Conservation and Development Trust (JCDT), “Dr. Tiny”, elucidated that the current ecological jeopardy within the BJCMs predominantly stems from the proliferation of non-native and invasive species. These species not only contest with indigenous flora and fauna for their habitat, thereby unsettling the ecological equilibrium, they also elevate the propensity for fires, further imperiling the area. The efforts to naturally regenerate deforested locales are similarly hindered by these invasive species and the occurrence of fires. Dr. Tiny highlighted the paradoxical impact of Maroon cultural practices, noting that the deliberate introduction of non-native plant species for culinary and medicinal purposes, coupled with both ceremonial and recreational fire-setting activities, significantly contributes to the dispersal of these invasive species.

Figure 5.

(a,b) Maroon fires during a religious Myal ceremony in the Blue Mountains, Jamaica. (© Jones Collection).

Despite the environmental concerns raised by such practices, the nuanced recognition of Maroon sovereignty by the state introduces a complex legal and jurisdictional landscape, thereby limiting the capacity for regulatory enforcement. Even with a predisposition towards engaging the Maroon community to mitigate the frequency and impact of forest fires, such an approach necessitates navigation across the intricate socio-legal terrain that delineates Maroon territories, thus presenting a formidable challenge in conservation efforts.

As a further challenge, under the framework of State Law, specifically delineated within Section 13(1d) of the National Park Regulations (1993) [32], it is an infraction to capture, annihilate, intentionally harm, or disturb any protected fauna, or to interfere with the nests or eggs of protected avian species without acquiring explicit authorization in writing from the Park Manager. While the state environmental regulatory bodies interpret pig-hunting—a practice traditionally undertaken by the Maroon communities—as contributing to species management, the hunting of coneys, which are traditionally utilized by Maroons in religious observances, both as sustenance and offerings to ancestral spirits, presents a legal and ecological paradox, given the protected status of this species. Dr. Tiny articulated concerns regarding the hunting of the coney, highlighting its distinction as Jamaica’s sole endemic non-volant mammal and its consequent protected status. The intensity of the hunting practices, inclusive of the destruction of coney habitats as a collateral effect of such activities, was expressed with alarm. Inquiries into the environmental repercussions of such practices were met with a notable absence of concern from the Maroon agricultural leadership, suggesting a reluctance to engage in discourse on this critical issue.

4.2. Legal Synergies and Dissonances: The Maroon Experience with State Environmental Enforcement Mechanisms

Contrastingly, the Maroons exhibit a robust custodial stance toward their aquatic ecosystems, particularly those within the Upper Rio Grande Valley, where pronounced apprehensions regarding the integrity of their waterways were communicated. Section 19 (1) and 19 (5) of the National Park Regulations (1993) [32] assert that fishing within a national park without the Park Manager’s written consent is illegal, particularly emphasizing the prohibition of fish capture using toxic substances, electrical discharges, or other analogous methodologies. The rivers and streams traversing the BJCMs are vital for the sustenance of a diverse array of freshwater flora and fauna. Yet, the practice of aquatic resource extraction using poisons and other hazardous chemicals, especially by younger community members for economic gain, poses a significant threat. Dr. Tiny and the Minister of Agriculture from the Moore Town Maroons, “Minister Theo”, pointed to a growing trend of environmental and ethical challenges associated with the poisoning of rivers for the extraction of fish and large shrimp (referred to locally as ‘janga’), unique to the BJCMs’ rivers, for lucrative sale outside the Maroon communities. This issue underscores a complex intersection of cultural practices, economic motivations, and environmental stewardship within the Maroon context. As articulated by representatives of the Maroon community, recent years have witnessed a burgeoning and recurrent issue whereby younger Maroons, specifically those below the age of 25, engage in the extraction of aquatic resources, notably fish and large shrimp (janga), through the utilization of toxic substances to contaminate river ecosystems. The harvested seafood is subsequently commercialized beyond the confines of the Maroon territories, yielding considerable financial returns. This practice raises significant ecological and cultural concerns, particularly given the unique presence of the janga species within the aquatic environments of the BJCMs in Jamaica.

In dialogue with a Park Ranger we refer to as “Ryan”, he revealed that, to his knowledge, no formal legal measures have been pursued against a Maroon for the act of river poisoning, largely attributable to the challenges inherent in procuring tangible evidence against the accused within Maroon domains. The initiation of state-led enforcement endeavors necessitates the direct apprehension of individuals during the act of poisoning, a criterion complicated by the jurisdictional ambiguities surrounding Maroon lands. This scenario underscores the complexities of state regulation and its applicability, or lack thereof, in areas traditionally recognized as Maroon territories. The absence of direct evidence precludes the establishment of legally valid grounds for the prosecution of offenders. Minister Theo further emphasized the problematic nature of river poisoning and its implications for environmental stewardship and cultural integrity within the Maroon community:

To the best of my knowledge, nobody from the Maroon community was ever convicted by the Courts. This is because when we complain about the poisoning, they [state law enforcement] say there is no evidence to prosecute. As acceptable evidence of the offence they say that both the shellfish and the water need to be tested immediately after the poisoning occurs. This requires that we Maroons collect a sample of the water in a clean container (because of course we walk around with clean containers everyday), then the sample must be frozen and transported to Kingston [Jamaica’s capital] quickly, which is very expensive. After this patriotic exercise, we have to pay for the lab test out of our own pocket, which costs more than the trip to Kingston. The process is burdensome, but they won’t accept photographs and eyewitness statements as evidence, only chemical evidence.(Minister Theo, 5 June 2018).

It merits particular attention that the Maroon leadership exhibits a readiness to engage with state mechanisms for enforcement purposes. This disposition towards leveraging state legislation for the enhancement of communal welfare intimates a potential for customary law to either be augmented by, or undergo modification in conjunction with, state law, as suggested by Allott (1980) [33]. Concurrently, Woodman (2011) [34] elucidates that customary legal frameworks may undergo evolution in response to shifts in the internal dynamics or societal attitudes prevalent within a community. Equally significant is the realization that, notwithstanding the Maroon authorities’ recourse to state intervention, the attainment of effective law enforcement or judicial action proved elusive. Testimonies from several Maroons delineated a sentiment of disillusionment regarding engagement with the Jamaican state apparatus in environmental legal matters, attributed primarily to ‘the lack of evidence,’ which consequently precluded the prosecution of environmental offences within judicial systems. Nevertheless, these respondents concurrently conceded that Maroon-led enforcement initiatives were ineffective in deterring violative conduct.

While the concept of legal pluralism eschews the doctrine of state-centric legalism—thereby challenging the notion of the primacy of state-enacted laws—these observations underscore a nuanced complexity within contexts of legal pluralism. Specifically, they illustrate that the presence of multiple avenues for legal redress against environmental transgressions does not inherently guarantee effective deterrent outcomes. This is largely due to challenges encountered in facilitating procedural synergies between the frameworks of state and customary laws in tangible applications.

4.3. Many Rivers to Cross: Generational Conflict and Environmental Governance

Beyond the complexities inherent in the harmonization of state and customary legal frameworks, the environmental degradation affecting aquatic ecosystems and species unveils underlying intra-community tensions. Specifically, the adoption of non-traditional fishing techniques has precipitated conflict within the community, emanating from a generational divergence in values concerning environmental stewardship and adherence to customary regulations. This discrepancy is particularly pronounced between older and younger segments of the Maroon population. While the latter group may exhibit a diminished regard for the principles of sustainable resource management, leading to infractions of local environmental norms, the former group—embodied by Maroon leadership—finds itself compelled to initiate enforcement measures to mitigate environmental transgressions, regardless of whether these are defined by state or Indigenous law frameworks. The reliance on an unwritten code of conduct, predicated on the collective conscience of the community to ensure adherence to environmental norms, appears to be waning, as evidenced by the escalating incidence of generational conflict as a principal factor contributing to intra-community environmental infringements.

The root causes of these generational conflicts can be traced to the foundational elements of Maroon communal institutions. The Maroon societal structure is deeply rooted in the historical context of the 1739 Treaty, further cemented through its unique political organization, religious practices, matrimonial alliances, kinship networks, and the Maroon agrarian economy, as documented by Besson (2016) [25]. Despite the legal autonomy historically accorded to the Maroons, demographic shifts have been observed, characterized by an increasing propensity for Maroons to migrate away from traditional lands and the selection of spouses from outside the Maroon community. Yet, lineage and descent continue to serve as the primary pillars underpinning the governance structure within Maroon society. The penetration and proliferation of external influences and cultural norms have eroded traditional respect for elders and customary Maroon legislations, particularly those governing environmental conservation, thereby exacerbating the challenges faced in maintaining ecological governance within the community.

The phenomena of cultural evolution and intergenerational discord have significantly eroded the perceived legitimacy of Maroon legal and authoritative frameworks amongst the younger cohorts within these communities. This erosion of legitimacy has rendered traditional enforcement mechanisms, historically effective in deterrence, less impactful on the younger generation. In Maroon societies, the custodianship of environmental wisdom and governance is traditionally vested in the elders, notably those constituting the Maroon council. Discourse with elder Maroons reveals that, historically, a reliance on local ecosystems coupled with robust community solidarity sufficed to ensure adherence to the tacit Maroon legal codes and the edicts of the Maroon council. This paradigm, however, has shifted markedly. An authority within the Maroon community indicated a perception among the elders that the younger members of the community display a diminished reverence for the natural environment. This diminished reverence is attributed to an attenuation in the transmission of Indigenous knowledge to the younger generation, undermining respect for both Maroon cultural practices and legal precepts. Conversely, the younger members of the Maroon communities articulate a nuanced understanding of Maroon customs, legal frameworks, and the authority of Maroon leadership. This divergence in perspectives highlights a fundamental challenge in the intergenerational transmission of knowledge and values, underscoring the complexities inherent in sustaining traditional ecological governance amidst evolving cultural and social landscapes.

One 18-year-old Maroon, referred to as “Anju”, expressed the following:

They [the elders] only teach us what they want to teach us. When we ask them to teach us the language [Kromanti] and how to use the herbs for healing, they say we are not ready yet. But at the same time they want us to dance for tourists and they want to tell us what to do and what not to do. Where have you ever seen that? If we can’t make money from the healing, we have to make money another way. They are preserving the fish but not the language. It can’t work. We are the younger ones coming up. If they don’t teach us, it is going die with them.(Anju, 15 December 2017).

Interviews with younger members of the Maroon community corroborate the perception of a disconnect in values between the generations. Notably, none of the young Maroons who engaged in our study were involved in formal employment sectors. The absence of vocational engagement, coupled with a discernible reluctance to participate in the burgeoning tourist economy, led to the inference that river poisoning is perceived by these young Maroons not solely as a facile avenue for generating income but also as a symbolic act of dissent against the traditional authority of Maroon elders. This scenario elucidates a broader spectrum of risks to environmental integrity within Maroon territories, manifesting through breaches of established local ordinances. The interplay of challenges in cultural perpetuation, compounded by a paucity of economic prospects and restricted avenues for youthful engagement in communal developmental initiatives, precipitates intergenerational strains, thereby diminishing social capital within these communities. Such strains catalyze increased migration away from Maroon settlements, further diluting the fabric of cultural unity.

Scholarship within the domain of environmental governance underscores the criticality of local stakeholder engagement in co-management frameworks to ensure the efficaciousness of conservation efforts (Bruner et al., 2001) [35]. In the Maroon community, such engagement necessitates the perpetuation of multigenerational traditional ecological knowledge through the intergenerational transmission of such wisdom. This is recognized as being pivotal for the facilitation of community-driven conservation strategies and the collaborative stewardship of natural resources (Olsson, Folke, and Berkes, 2004) [36]. Should the noted dynamics between the Maroon elders and youth persist unmitigated, the resultant depletion in social capital threatens to compromise the efficacy of Maroon environmental stewardship and weaken assertions of legal and environmental sovereignty. The gradual erosion of the transmission of cultural and Indigenous practices, which serve to delineate Maroon identity from the broader Jamaican populace, portends a future wherein Maroons may increasingly fall under the purview of state-enforced environmental governance. This potential shift underscores the critical need for interventions that bridge generational divides, fostering the continuity of Maroon heritage and reinforcing the community’s autonomous governance structures in the face of evolving environmental and social challenges.

4.4. Park Rangers and State Deference to Maroon Governance

The preceding analyses elucidate that state authorities are cognizant of the pollution affecting Maroon rivers and other environmental violations within state jurisdiction. Nonetheless, an insufficient understanding of Maroon cultural practices, rituals, and assertions of autonomy has impeded the initiation of enforcement measures against violators. This context foregrounds an additional critical theme: the reverence for the supernatural influence ascribed to ancestral spirits transcends the Maroon community, permeating the perspectives of Park Rangers operating within the BJCMs. Such reverence, coupled with linguistic barriers—specifically, the lack of proficiency in the Maroon dialect of Kromanti among Park Rangers—contributes to a reluctance to pursue legal recourse against the Maroons. A Park Ranger, “Chris”, articulated this sentiment, highlighting the multifaceted challenges faced by state enforcement personnel in navigating the complex socio-cultural and spiritual landscape that characterizes the Maroon community:

I don’t really mess with them [the Maroons] you know. You know how much people they set obeah [curses] on? I never became a Ranger for that. I have my family to go home to. I hear about things [environmental infractions], yes. The way I see it though we can’t do anything about it. We have plenty other challenges that can be addressed. We need more resources, we’re just now getting a camera to collect evidence. The GPS devices are outdated so we need some new ones. You understand?(Chris, 11 May 2018).

Corroborating the aforementioned stance, observations made during fieldwork revealed a conspicuous absence of personnel at the Ranger Station proximal to the Upper Rio Grande Valley, a locus of Maroon activity within the BJCMs. This observation is further substantiated by Ryan’s acknowledgment that, to his knowledge, there has been an absence of state-initiated enforcement actions against the Maroons for environmental infractions. Ryan’s assertion is also supported by data from the National Environmental Protection Agency, which do not reflect any enforcement activities against any Maroon in the five-year timeframe between 2014 and 2019. Evidently, the enduring lack of collaborative engagement underscores the complex interplay of legal and cultural pluralism characteristic of the BJCMs.

The observable reticence of BJCM Park Rangers to exert authority, even in collaboration with Maroon leaders, underscores a broader reluctance on the part of the Jamaican state to leverage its legal apparatus in supporting enforcement within Maroon territories. Consequently, the onus of decision making in response to environmental transgressions is predominantly placed upon the Colonels within the Maroon hierarchy, who deliberate on whether or not to try to continue to engage with state mechanisms for remedial actions. Nonetheless, the Maroons’ predilection for basing enforcement decisions on supernatural rationales further entrenches a prevailing distrust towards state entities. This inclination not only reflects deep-seated cultural and spiritual values, it also underscores a political strategy aimed at preserving the opacity of Maroon authority. Such practices serve to safeguard the autonomy of Maroon governance structures, yet they also perpetuate a cycle of mutual suspicion and limited cooperation between Maroon communities and state regulatory bodies, complicating efforts towards unified environmental stewardship.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Within the sphere of legal and cultural pluralism, it is commonplace for there to emerge both points of alignment and discord between state-enacted legal frameworks and Indigenous customary laws. This study elucidates various facets of Maroon society that embody their cultural, legal, and spiritual engagements with environmental governance, revealing substantial areas of potential synergy between Maroon customs and the environmental regulatory schema of the Jamaican state. Despite a historical backdrop characterized by political friction, particularly concerning the recognition of Maroon territorial claims and governance authority, and notwithstanding the disparate sources of authority and methodologies for the formulation and execution of environmental legislation, the overarching aim remains consistent across both entities: the governance of environmental resources within the BJCMs.

In spite of these potential areas of concordance, practical applications of environmental governance manifest significant disparities and points of contention. The Jamaican state’s approach to environmental regulation within the BJCM is marked by a legalistic and universalist stance, often neglecting the nuances of local conditions and cultural practices. In contrast, Maroon society addresses environmental breaches through a prism of contextual justice, as posited by Zips (1996) [37], who assesses the motivations underlying specific unlawful behaviors. Consequently, for the Maroons, the application of environmental laws is inherently more adaptive and variable.

A further critical distinction lies in the mechanisms of surveillance and enforcement employed by the Jamaican state versus those of the Maroon communities. While the state is endowed with the legal authority to oversee the BJCMs through a suite of statutes and regulatory agencies, its actual investment in monitoring and enforcement activities is minimal. Conversely, Maroon leadership actively engages in oversight functions, with Maroon councils and community members collaboratively partaking in punitive measures against ecological violations in accordance with their traditional laws. This divergence underscores the complexity of implementing effective environmental governance within contexts characterized by dual legal and cultural paradigms.

The dynamics of legal and cultural pluralism within the BJCMs occupy a nuanced position in relation to environmental governance. It is not straightforward to assert that pluralism is a direct causative factor for environmental degradation within the BJCMs, given the shared commitment of both state and Maroon authorities towards environmental conservation. Each entity demonstrates support for environmental regulations through various mechanisms, including funding, monitoring, and enforcement activities. However, pluralism does contribute to challenges in coordinated enforcement against certain environmental violations. For instance, despite Maroon efforts in surveilling illicit fishing activities, such actions have not served as an effective deterrent. Concurrently, the state’s insistence on rigorous evidence for prosecutorial action presents practical difficulties, contributing indirectly to environmental harm by emboldening violators through perceived enforcement gaps.

Nevertheless, pluralism holds potential as a catalyst for enhanced environmental governance, predicated on the mutual conservation interests of state and Maroon entities. Achieving this necessitates an acknowledgment of the interdependent relationship between state-enforced laws and non-state legal systems. The Maroons exhibit a protective stance towards the environment, aligning with state objectives, while the state possesses the capabilities for evidence documentation and enforcement augmentation, which can bolster the legitimacy of Maroon legal frameworks and authority. The crux of advancing environmental governance lies in fostering improved coordination between Maroon and state actors, be it through Park Ranger collaboration or the integration of scientific resources for evidence substantiation.

The future of robust environmental governance within the BJCM hinges on the strategic navigation of the relationship between the Jamaican state and the Maroons, particularly in the context of legal and cultural pluralism. Formal recognition by the state of Maroon non-state legal systems, without granting exclusive jurisdiction, coupled with the state’s restrained exercise of regulatory oversight, underscores a de facto cession of autonomy to the Maroons. This autonomy enables the Maroons to establish governance structures, a fact reaffirmed by the findings of this study, suggesting a framework within which the potential for collaborative environmental stewardship may be realized.

The manifestation of legal and cultural pluralism within the context of Maroon and state relations is not without its challenges, as underscored by the joint incapacity of Maroon and state authorities to curtail illicit fishing practices involving toxic substances, alongside the state’s reticence to engage within Maroon jurisdictions. A significant limitation inherent in this pluralistic arrangement is the state’s failure to bolster the non-state Maroon governance system with either enforcement support or resources. This deficiency harbors the potential for the encroachment upon human rights and the principles of natural justice under the guise of upholding tradition, as identified by Forsyth (2009, p. 214) [38]. Maroon participants in this study reported unsuccessful endeavors to solicit state support for the enforcement of laws concerning river poisoning, hoping for a reversion to traditional Maroon punitive measures, occasionally resulting in physical repercussions for violators. Notwithstanding the historical narrative of Maroon resistance to subjugation, this investigation reveals a potential inclination among Maroon communities towards collaboration with the state, contingent upon the state’s endorsement of environmental stewardship without compromising Maroon legal sovereignty. The current stance of state non-intervention in Maroon legal matters, while ostensibly preserving Maroon autonomy, fails to adequately support environmental governance, meeting only one of the dual prerequisites identified by Maroons.

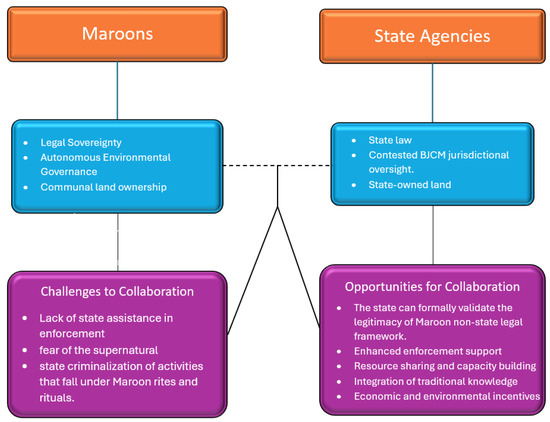

Consequently, there emerges a call for an evolved form of legal pluralism, wherein (1) the state expressly validates the legitimacy of the Maroon non-state legal framework and (2) commits to aiding in the enforcement of Maroon legal directives upon request. This appeal gains further pertinence against the backdrop of the state’s formal recognition of Maroon heritage for tourism-related economic benefits, which accrue to both Maroons and the state alike. A deliberate choice by the state to recognize and materially endorse Maroon legal authority, rooted in Maroon heritage, promises to yield mutual environmental and economic dividends. Such formal recognition could lay the groundwork for initiating dialogues with Maroon communities, aimed at reconciling shared interests and divergences in environmental governance perspectives. The potential for collaboration between Maroon communities and the state represents a pivotal opportunity to foster participatory decision making in the development and application of environmental regulations. While the feasibility of such a partnership is apparent, its realization is fraught with challenges. Historically, Maroons have harbored a deep-seated mistrust towards state entities, a sentiment rooted in their enduring struggle for land rights and legal independence. Similarly, state representatives, such as Park Rangers, exhibit apprehensions regarding Maroon intentions. As reflected in Figure 6, despite these hurdles, a dialogue centered around shared objectives and the mutual benefits of legal pluralism could yield significant advantages for both parties.

Figure 6.

State–Maroon collaborative opportunities and challenges in the Blue and John Crow Mountains (BJCMs).

The inception of such cooperative endeavors might necessitate a critical reassessment by the Maroons of their prevailing perceptions, particularly the notion that seeking state aid constitutes a diminution of their juridical sovereignty. An essential paradigm shift involves recognizing the alignment of state and Maroon conservation objectives and acknowledging the potential enhancement of Maroon regulatory efforts through state-supported enforcement mechanisms. This acknowledgment would demand from the Maroons an openness to augmenting their traditional environmental regulations with state resources, a proposition that might challenge their deeply ingrained sense of self-reliance and autonomy. The historical context of unmet expectations, where the state has previously failed to respond adequately to Maroon solicitations for assistance in addressing environmental infringements, further complicates this dynamic. Nonetheless, without state collaboration, Maroon regulations alone may prove insufficient in ensuring compliance.

For the state, acknowledging Maroon sovereignty has been a step forward, yet building trust will necessitate a formal and unequivocal recognition of Maroon laws as being on an equal footing with state legislation. This approach, rather than leaving Maroons to autonomously navigate environmental governance—which may not always yield effective outcomes—encourages a reconsideration of state support. Our research suggests that a strategy not predicated on imposing external regulations, but rather on affirming local institutions and celebrating environmental governance successes, could pave the way for a more reciprocally open dialogue about the environmental challenges faced by Maroon communities. Thus, the cornerstone of establishing a fruitful partnership hinges on embracing the fluidity inherent in Maroon culture and legislative processes, with an eye towards forging a synergistic relationship with the state. This endeavor becomes increasingly pertinent as younger generations within Maroon communities begin to scrutinize the legitimacy of their leadership. A constructive engagement that respects local autonomy while providing recognition and support can serve as a foundation for mutual trust and collaborative environmental stewardship.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.S.-J.; methodology, T.S.-J.; formal analysis, T.S.-J.; investigation, T.S.-J.; data curation T.S.-J.; writing—original draft preparation, T.S.-J.; writing—review and editing, T.S.-J. and S.P.; visualization, T.S.-J. and S.P.; project administration, T.S.-J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of UF Institutional Review Board (protocol code 201701103 and date of approval 25 April 2017.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, T.S.-J., upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Becker, E. The Power of Social Movements and the Limits of Pluralism: Tracing Rastafarianism and Indigenous Resurgence Through Commonwealth Caribbean Law and Culture. Int. J. Leg. Inf. 2015, 43, 136–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca Lindao, G.; Arroyo De La Ossa, M.; Castellanos Suarez, J.A. Environmental Governance with an Ethnic Approach: A Management Commitment in Protected Areas in the Colombian Caribbean. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agrícolas 2022, 13, 905–915. [Google Scholar]

- North, D.C. Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Baud, M.; De Castro, F.; Hogenboom, B. Environmental Governance in Latin America: Towards an Integrative Research Agenda. Eur. Rev. Lat. Am. Caribb. Stud. 2011, 90, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamanaha, B.Z. A Non-Essentialist Version of Legal Empowerment. J. Law Soc. 2000, 27, 296–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delville, P.L. Harmonising Formal Law and Customary Land Rights in French-Speaking West Africa; Report No. 86; IIED: Senegal, Africa, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick, D. ‘Best Practice’ Options for the Legal Recognition of Customary Tenure. Dev. Change 2005, 36, 449–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, J. What Is Legal Pluralism? J. Leg. Plural. Unoff. Law 1986, 18, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinhans, M.M.; Macdonald, R.A. What Is a Critical Legal Pluralism? Can. J. Law Soc./La Rev. Can. Droit Et Société 1997, 12, 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merry, S.E. McGill Convocation Address: Legal Pluralism in Practice. McGill Law J. 2013, 59, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twining, W. Normative and Legal Pluralism: A Global Perspective. Duke J. Comp. Int’l L 2009, 20, 473. [Google Scholar]

- Gover, K. Legal Pluralism and State-Indigenous Relations in Western Settler Societies; International Council on Human Rights Policy: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bilby, K.M. True-Born Maroons; University of Florida Press: Gainesville, FL, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Pimentel, D. Can Indigenous Justice Survive? Legal Pluralism and the Rule of Law. Harv. Int. Rev. 2010, 32, 32. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, P. Legal Pluralism in Conflict: Coping with Cultural Diversity in Law; Routledge-Cavendish: Abingdon, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan, M.B.; Thompson, B.; Ayers, A.L. Pāwehe Ke Kai a ‘o Hā‘ena: Creating State Law Based on Customary Indigenous Norms of Coastal Management. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2017, 30, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsyth, M. A Bird That Flies with Two Wings: Kastom and State Justice Systems in Vanuatu; ANU Press: Canberra, Australia, 2009; p. 298. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. Polycentric Systems for Coping with Collective Action and Global Environmental Change. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2010, 20, 550–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, K.E.; Lund, J.F. The Politics of Expertise in Participatory Forestry: A Case from Tanzania. For. Policy Econ. 2015, 60, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbulut, B.; Soylu, C. An Inquiry into Power and Participatory Natural Resource Management. Camb. J. Econ. 2012, 36, 1143–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohannan, P. The Differing Realms of the Law. Am. Anthropol. 1965, 67, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starr, J.; Collier, J.F. History and Power in the Study of Law: New Directions in Legal Anthropology. In Anthropology of Contemporary Issues; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Diver, S. Co-management as a Catalyst: Pathways to Post-colonial Forestry in the Klamath Basin, California. Hum. Ecol. 2016, 44, 533–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besson, J. Transformations of Freedom in the Land of the Maroons: Creolization in the Cockpits, Jamaica; Ian Randle Publishers: Kingston, Jamaica, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Madrilejo, N.; Lombard, H.; Torres, J.B. Origins of Marronage: Mitochondrial Lineages of Jamaica’s Accompong Town Maroons. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 2015, 27, 432–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, G.; Bunce, A.; Johnson, L. How Many Interviews Are Enough? An Experiment with Data Saturation and Variability. Field Methods 2006, 18, 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrest, C.; Corrin, J. Legal Pluralism in the Pacific: Solomon Island’s World War II Heritage. Int. J. Cult. Prop. 2013, 20, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, J.A. Avoiding traps in member checking. Qual. Rep. 2010, 15, 1102–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padgett, D.K. Does the Glove Really Fit? Qualitative Research and Clinical Social Work Practice. Soc. Work 1998, 43, 373–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods: Integrating Theory and Practice; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Tamanaha, B.Z. The Folly of the ‘Social Scientific’ Concept of Legal Pluralism. J. Law Soc. 1993, 20, 192–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allott, A. The Limits of Law; Butterworths: London, UK, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Woodman, G.R. A Survey of Customary Laws in Africa in Search of Lessons for the Future. Future Afr. Cust. Law 2011, 9, 12–15. [Google Scholar]

- Bruner, A.G.; Gullison, R.E.; Rice, R.E.; Da Fonseca, G.A. Effectiveness of Parks in Protecting Tropical Biodiversity. Science 2001, 291, 125–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olsson, P.; Folke, C.; Berkes, F. Adaptive Comanagement for Building Resilience in Social–Ecological Systems. Environ. Manag. 2004, 34, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zips, W. Laws in Competition: Traditional Maroon Authorities within Legal Pluralism in Jamaica. J. Legal Plur. Unoff. Law 1996, 28, 279–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsyth, M. How Can the Theory of Legal Pluralism Assist the Traditional Knowledge Debate. Intersect. Gend. Sex. Asia Pac. 2013, 33, 1–41. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).