Abstract

Oxidative stress is caused by an imbalance between the production and subsequent accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in cells and tissues and the capacity of a biological system to eliminate these reactive substances. Systemic oxidative stress biomarkers in plasma, serum, urine, or red blood cells have been found to be elevated in many diseases, including skin cancer. UV radiation (UVR) induces damage to biomolecules that enter the bloodstream, reinforcing systemic oxidative stress. On the other hand, pre-existing systemic oxidative stress does not supply the skin with the adequate micronutrients and antioxidant resources to ameliorate the skin’s antioxidant defense against UVR. In both scenarios, skin cancer patients are exposed to oxidative conditions. In the case of warts, oxidation is linked to chronic inflammation, while impaired cutaneous antioxidant defense could ineffectively deal with possible oxidative stimuli from viral agents, such as HPV. Therefore, the aim of our study is to evaluate the existing data on systemic oxidative stress in skin diseases such as non-melanoma skin cancer (NMSC), basal-cell carcinoma (BCC), squamous-cell carcinoma (SCC), and melanoma as well as benign lesions such as actinic keratosis (AK), sebaceous keratosis (SK), and warts. Previous studies have demonstrated that patients with NMSC, melanoma, AK, and warts (both genital and non-genital) are subjected to severe oxidative stress, indicated by disturbed antioxidant enzyme levels, accumulated oxidized proteins and lipid products, and, to a lesser extent, lower concentrations of micronutrients. Interestingly, medical history of NMSC or melanoma as well as stage of skin cancer and treatment approach were found to affect systemic oxidative stress parameters. In the case of warts (both genital and non-genital), high oxidative stress levels were also detected, and they were found to be aligned with their recalcitrant character.

1. Introduction

1.1. The Concept of Oxidative Stress

Oxidative stress is a term used to describe a disturbance of equilibrium between the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) within cells and tissues and the ability of a biological system to eliminate these reactive substances. ROS include radical and non-radical oxygen derivatives formed by the partial reduction of oxygen such as superoxide anions (O2•−), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and hydroxyl radicals (HO•) [1]. External stressors, like UV radiation, ionizing radiation, pollutants, and heavy metals, along with xenobiotic substances like anticancer drugs substantially raise ROS production. Excessive levels of ROS cause harmful outcomes and, if not mitigated adequately by the enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidant mechanisms of the targeted cell or tissue, they induce modifications of significant biomolecules, processes implicated in the pathophysiology of diseases [1]. It is worth mentioning that ROS serve a dual role in living systems, contributing to important cellular functions in low or moderate levels. More specifically, they act beneficially as mediators of immunity [2] and intracellular signaling pathways [3]. They are also involved in cellular proliferation, differentiation, and programmed cell death [4].

In order to determine oxidative stress levels, most studies evaluate the enzymatic and non-enzymatic mechanisms activated by a given cell, tissue, or organism to deal with the oxidative changes mediated by the contributing stressor. Usually, the findings are compared with the respective results in the control group or individuals that were not exposed to the oxidative factor. In the case of disease, in the majority of cases, patients with a specific disease and occasionally with certain eligible criteria (a certain disease severity or patients without any intervention or medical treatment, etc.) are compared to disease-free individuals in terms of oxidative stress parameters. These parameters can be evaluated in erythrocytes, biological fluids (plasma, serum, or urine), or a specific tissue (for example a skin biopsy), reflecting the redox status of the specific system [5].

The most important enzymes that cells are armed with are superoxide dismutase (SOD), glutathione peroxidase (GPX), glutathione reductase (GR), and catalase (CAT). Firstly, SOD catalyzes the dismutation of superoxide anion free radicals (O2•−) into molecular oxygen and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). Secondly, hydrogen peroxide is subsequently reduced to water by the enzymatic actions of GPX and CAT [1]. GPx catalyzes this reaction via the oxidation of reduced GSH into its disulfide form (GSSH), while GR replenishes cellular GSH levels by converting GSSG into its reduced form using NADPH as a cofactor [6]. Studies usually determine the activity of those enzymes to assess oxidative stress. For example, reduced GPx-1 activity can increase vulnerability to oxidative stress by permitting the buildup of ROS, while excess GPx-1 might foster reductive stress, marked by an insufficient presence of necessary ROS required for cellular signaling functions [6].

Non-enzymatic molecules can also have antioxidant capacities, inactivating radicals and oxidants. Minerals exert their antioxidant action through involvement in certain enzymatic reactions. For example, in the case of Zn, the SOD1 enzyme comprises an eight-stranded β-barrel with one Cu and Zn ion bound in each monomer. Their presence is crucial for the catalytic activity of the enzyme. Besides this, zinc competes with iron (Fe) and copper (Cu) ions for binding to cell membranes and proteins, displacing these redox-active metals, which catalyze the production of ⋅OH from H2O2 [7]. Generally, the most important antioxidant micronutrients are vitamins A, C, and E, copper, zinc, and selenium [8].

Besides the focus on innate protection against oxidative stress, it is common for studies to assess the impact of oxidative stress on cellular components like DNA, lipids, and proteins. Oxidative modifications can lead to the production of 8-oxoguanine (also called 8-hydroxyguanine), a tautomer of guanine in nucleic acids that is formed when DNA is exposed to excessive ROS. As a result, 8-oxoguanine has gained significant recognition as a biomarker of oxidative damage [9]. As an index for lipid peroxidation, thiobarbituric acid reactive substance (TBARS) assay is a frequently used method. This assay measures malondialdehyde (MDA), a breakdown product originating from the oxidation of lipid substrates, specifically from an endoperoxide of unsaturated fatty acids [10]. 15-F2t-isoprostane is also a lipid peroxidation product that is a frequently used oxidative stress marker [11].

As for the impact of oxidative stress on proteins, protein carbonylation, which is the most common form of protein oxidation, is an irreversible process that promotes protein degradation. Advanced byproducts of lipid peroxidation such as 4-Hydroxy-2-nonenal (4-HNE) and MDA, regarded as reactive carbonyl species, have been correlated with protein modifications [12]. Another relevant mechanism involves the oxidation of sulfur-containing amino acids, present in thiols [13]. These intracellular compounds are especially susceptible to direct oxidation by ROS due to their strong nucleophilic properties. The oxidation of these thiols leads to changes in the structure and function of proteins [12,13].

Regarding antioxidant micronutrients, vitamin A, or retinol, and carotenoids exhibit their antioxidant properties through a hydrophobic chain composed of polyene units. This chain has the capability to extinguish singlet oxygen and to counteract thiol radicals, as well as to enhance the stability of peroxyl radicals. Secondly, vitamin C is chemically capable of reacting with most of the physiologically important radicals and oxidants and acts as a proven hydrosoluble antioxidant, while vitamin E is a fat-soluble antioxidant that terminates the production of ROS that forms when fat undergoes oxidation. Therefore, the recognition of a reduced quantity of serum macronutrients may be indicative of oxidative stress [14].

It is important to outline that each study may use a different technique or different protocol to assess the same oxidative stress parameter, rendering the exclusion of definite or additive conclusions challenging. Also, it is worth mentioning that oxidative stress markers can differ between several samples of the same organism (tissue or type of cell). For example, in the case of psoriasis, in research conducted by Yldirim and colleagues, serum MDA levels in individuals with psoriasis were not notably elevated compared to those in the control group. Nonetheless, higher lipid peroxidation levels were observed in samples obtained by lesional skin biopsies, indicating different oxidative stress parameters between cutaneous and systemic oxidative stress [15].

1.2. Oxidative Stress in Dermatology—The Interaction between Cutaneous and Systemic Oxidative Stress

Oxidative stress has been widely investigated in dermatology and skin diseases. Reviews focusing on common dermatoses such as acne [16], psoriasis [17], and atopic dermatitis [18] have been published recently, indicating it as a contributor factor in the pathogenesis of the focus disease. Oxidative stress is considered part of the internal exposome and, along with other contributors such as genetic variants and internal organism characteristics like the microbiota and metabolics, predisposes an individual to disease. External contributors, including diet and exercise, in turn affect systemic oxidative stress [19]. However, a question occurs on how a skin disease, or a skin stressor, can affect systemic oxidative stress and, on the contrary, how the latter is associated with cutaneous oxidative stress.

As mentioned previously, exposure to ultraviolet radiation (UVR) serves as the primary trigger for ROS production in the skin and the main etiology of skin cancer. The spectrum of wavelengths responsible for this effect predominantly falls within the UVA range (320–400 nm), although there is some overlap with the UVB region (280–315 nm). The process of ROS generation following UVA and UVB irradiation is based on the absorption of photons by intrinsic photosensitizer molecules like cytochromes, riboflavin, heme, and porphyrin. Following exposure to sunlight, damaged biomolecules and signaling molecules resulting from UV exposure can permeate into the bloodstream, thereby inducing systemic oxidative stress. Also, skin cancer cells produce excessive ROS by themselves [20]. This is the reason why skin cancer patients tend to have high levels of systemic oxidative stress [21]. Also, patients with certain gene polymorphisms have misfunctioning antioxidant enzymes [22]. In this case, the default found in red blood cells (RBCs) would be present in every cell of the same organism, including skin keratinocytes, fibroblasts, and melanocytes, forming a generalized flawed antioxidant defense [23]. As for inflammatory dermatoses, systemic inflammation corresponds to systemic oxidative stress [24].

The reverse relationship has been also observed, indicating that systemic oxidative stress can affect skin integrity. Notably, the consumption of certain antioxidants can ameliorate systemic oxidative stress and subsequently reduce skin disorder severity. For example, flavonoids can act beneficially, as they can repair damaged biomolecules and enhance the activities of antioxidant enzymes such as superoxide dismutase, catalase, and glutathione peroxidase respectively. In the case of skin cancer patients, it has been proven that dietary flavonoid-rich polyphenols exert skin-protective effects against the potential hazards of UV-induced skin cancers by reducing cutaneous inflammation and oxidative stress [25].

1.3. Oxidative Stress and Skin Cancer

Skin cancer encompasses melanoma and non-melanoma skin cancer (NMSC) and represents the most prevalent form of cancer among individuals of Caucasian ethnicity. Non-melanoma skin cancers predominantly comprise basal-cell carcinoma (BCC) and cutaneous squamous-cell carcinoma (SCC), alongside some less common skin tumors. BCC originates from the basal layer of the epidermis and its associated structures, whereas SCC emerges from the unregulated growth of atypical epidermal keratinocytes. Melanoma, a malignant tumor arising from melanocytes, is the deadliest form of skin cancer, being capable of metastasizing to both regional and distant sites [26].

1.3.1. Oxidative Stress and NMSC

NMSC initiation is influenced by a combination of environmental triggers, phenotypic characteristics (including lighter skin tones with less natural protection), and genetic factors that make the individual more prone to oxidative stress in the skin microenvironment. Among environmental factors, exposure to UVR stands out as the most significant risk factor, due to the induction of DNA damage, particularly in the UVB range of 290–320 nm, which produces two major types of lesions: cyclobutene pyrimidine dimers (CPDs) and 6–4 photoproducts (6-4PPs). If this damage is not repaired by nucleotide excision repair mechanisms, its products can disrupt proper base-pairing and impede vital cellular processes such as transcription and replication [5,27]. These harmful modifications may lead to progressive alterations in genes, including tumor suppressor genes and proto-oncogenes, eventually resulting in the formation of tumors. In the case of BCC, for example, exposure to UVR and oxidative stress promote mutations in the PTCH (patched-1) gene located on the cell membrane, resulting in an abnormal activation of the hedgehog signaling pathway. This, in turn, plays a significant role in the development of BCC [28]. Newer studies make efforts to relate oxidative stress and skin cancer, especially NMSC, with a third parameter, more frequently a third exposome variant such as the skin microbiome [29] and vitamin D adequacy [5].

1.3.2. Oxidative Stress and Melanoma

Considering cases of NMSC, melanoma is related to exceptionally high oxidative stress levels. Melanocytes, due to their physical location, are directly exposed to environmental stressors, such as UV radiation, that induce oxidative stress. Also, melanocytes are particularly susceptible to oxidative changes due to the pro-oxidant state generated during the synthesis of melanin and the intrinsic antioxidant defenses that may be disrupted in pathologic conditions. Damaged cellular components formed by elevated ROS disturb the structural integrity and functionality of cells. Ion channels can be stimulated or blocked depending on the intensity of oxidative stress, determining melanoma progression. As a consequence, ion channels and oxidative stress may serve as possible therapy targets [30,31].

1.4. Oxidative Stress and Benign Skin Lesions

Data regarding benign skin lesions and oxidative stress seem to be less abundant compared to those on skin cancer, probably due to the benign nature of the lesions. Actinic keratosis results from UV-provoked dysplastic proliferations of keratinocytes with the potential for malignant transformation, considered pre-malignant lesions. Actinic keratosis tends to follow, just as skin cancer, the general terms of UV-induced oxidative stress discussed above [5]. Secondly, seborrheic keratoses (SKs) are very common benign epithelial skin tumors due to skin aging, chronic UV exposure, and possibly the involvement of HPV [32]. The above-mentioned etiological factors are closely related to oxidative stress.

1.5. Oxidative Stress and Warts

Warts are mucocutaneous growths caused by the human papillomavirus (HPV). To date, over 200 different types of HPV have been identified, with warts commonly associated with HPV types 1, 2, 4, and 7. In immunosuppressed patients, HPV types 75, 76, and 77 have been observed. HPV infects host cells without integrating viral DNA into the host genome. In the case of HPV infection, viral infection does not trigger a state of prolonged inflammation. This is primarily due to the fact that the virus initially infects basal epithelial cells, which are protected from circulating immune cells during the early phases of infection. However, it is worth noting that ROS and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) could potentially play a role in the progression of viral-induced wart formation and, rarely, HPV-related carcinogenesis. Oxidative stress can significantly impact both processes, ultimately establishing favorable conditions for effective viral integration. Then, HPV-transformed cells may avoid apoptosis by the expression of the viral E6 protein, which promotes the ubiquitination and subsequent proteolytic degradation of the cellular protein p53. Furthermore, oxidative-stress-mediated regulation of viral oncogenes at the level of transcriptional activation may lead to HPV carcinogenesis [33]. Beyond the skin, oxidative stress has been found to be present in patients with HPV-related CIN [34] and medical history of multiple HPV infections [33].

Both skin cancer and lesions with benign and pre-malignant capacities are related to oxidative stress. In studies evaluating oxidative stress parameters of patients with skin diseases, authors tend to give a more holistic approach by measuring systemic oxidative stress in patients’ blood samples [5]. However, this assessment might reflect oxidative stress caused by other systemic diseases such as hypertension, diabetes, and a medical history of heart attacks. Systemic oxidative stress is a general but important term which includes processes ranging from damage at the cellular level to aging and traces of immune dysfunction in antioxidant mechanisms that can result in disease development. Therefore, our review aims to collect studies focused on systemic oxidative stress in NMSC and melanoma as well as patients with benign lesions (AK, SK, and warts), provide a biological-system-specific assessment of skin disease patients, and further investigate the vicious circle between systemic and cutaneous oxidative stress.

2. Result and Methods

In order to perform our narrative review, we searched PubMed articles published until the end of April 2023 based on terms such as “melanoma” OR “Non-melanoma skin cancer” OR “BCC” OR “cutaneous SCC” OR “actinic keratosis” OR “seborrheic keratosis “ OR “ warts” AND “oxidative stress” OR “glutathione” OR “catalase” OR “ TBARS” OR “ carbonyls” OR “ vitamin A” OR “ vitamin C” OR “zinc” OR “selenium” OR “ vitamin E”. Where no results were found, we expanded our research beyond PubMed. Eligible criteria were references to systemic oxidative stress parameters in skin cancer patients or patients with benign lesions such as actinic keratosis and seborrheic keratosis and their comparison with the respective parameters in a control group. As systemic oxidative stress markers, we considered oxidative stress parameters assessed either in the bloodstream, plasma, serum, RBCs, or urine. Excluded studies were those that assessed only cutaneous and not systemic oxidative stress and those that determined alterations in oxidative stress following antioxidant supplementation. Comparisons based on child populations were excluded.

Following our research, we found fourteen studies on NMSC, fifteen studies on melanoma, four studies on benign lesions (we expanded our research on SK, as no results were found on PubMed, and we included one study on SK), and seven studies on warts. In the following tables, the selected studies are presented, including references, the biological system based on which oxidative stress parameters were assessed, redox biomarkers, the method used, and the outcome of the comparison. Statistical significance was determined by the original studies.

BCC patients were detected in ten studies, of which three reported enzymatic mechanisms, five included oxidative stress byproducts, and seven reported antioxidant vitamin concentrations. The studies revealed 50 comparisons between BCC patients and other groups, such as healthy individuals, patients with another type of NMSC, patients with medical history of NMSC excision, or patients with AK. Comparison of BCC patients with patients with AK or SCC is indicative of a comparison with sun-exposed patients.Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5 detail studies on NMSC patients, Table 6, Table 7 and Table 8 on melanoma patients, Table 9 on benign lesion patients, and Table 10 and Table 11 on wart patients.

Table 1.

Comparisons of enzymatic antioxidants (catalase, glutathione peroxidase (GPx), superoxide dismutase (SOD), and NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1)) detected in BCC patients with a comparison study group. The method used is described in each case. The results refer only to statistically significant differences found by the authors of the respective studies.

Table 1.

Comparisons of enzymatic antioxidants (catalase, glutathione peroxidase (GPx), superoxide dismutase (SOD), and NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1)) detected in BCC patients with a comparison study group. The method used is described in each case. The results refer only to statistically significant differences found by the authors of the respective studies.

| Study | Patients | Tested | Method Used | Redox Biomarker | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [5] | BCC vs. control | Erythrocytes | [35] | Catalase (U/mg Hb) | No significant difference detected |

| [5] | BCC vs. AK | Erythrocytes | [35] | Catalase (U/mg Hb) | No significant difference detected |

| [5] | BCC vs. SCC | Erythrocytes | [35] | Catalase (U/mg Hb) | No significant difference detected |

| [36] | BCC vs. control | Plasma | Kit protocol from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI, USA) | Catalase activity (unit/mg protein) | Lower in BCC patients than control |

| [36] | BCC vs. medical history of NMSC (BCC) | Plasma | Kit protocol from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI) | Catalase activity (unit/mg protein) | Lower in BCC patients than NMSC-excised patients |

| [36] | BCC vs. control | Plasma | [37] | GPx (unit/mg protein) | Lower in BCC patients than control |

| [36] | BCC vs. medical history of NMSC (BCC) | Plasma | [37] | GPx (unit/mg protein) | Lower in BCC patients than NMSC-excised patients |

| [36] | BCC vs. control | Plasma | [38] and kit protocol from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI) | SOD (unit/mg protein) | Higher in BCC than control |

| [36] | BCC vs. medical history of NMSC (BCC) | Plasma | [38] and kit protocol from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI) | SOD (unit/mg protein) | No significant difference detected |

| [36] | BCC vs. control | Plasma | [39] | NQO1 (µmol 2,6-dichloroindophenol reduced/min/mg protein) | Lower in BCC patients than control |

| [36] | BCC vs. medical history of NMSC (BCC) | Plasma | [39] | NQO1 (µmol 2,6-dichloroindophenol reduced/min/mg protein) | Lower in BCC patients than NMSC-excised patients |

Interestingly, three studies [5,36,40] included eleven comparisons concerning antioxidant enzymes, four of which showed no statistically significant differences (Table 1). Worth mentioning is NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1), which is a crucial cellular defense enzyme against oxidative stress.

Table 2.

Comparisons of non-enzymatic antioxidants, including metabolic antioxidants and dietary micronutrients, detected in BCC patients compared with a study group.

Table 2.

Comparisons of non-enzymatic antioxidants, including metabolic antioxidants and dietary micronutrients, detected in BCC patients compared with a study group.

| Study | Patients | Tested | Method Used | Redox Biomarker | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [5] | BCC vs. control | Erythrocytes | [35] | GSH (μmol/g Hb) | Lower in BCC patients than control |

| [5] | BCC vs. AK | Erythrocytes | [35] | GSH (μmol/g Hb) | No significant difference detected |

| [5] | BCC vs. SCC | Erythrocytes | [35] | GSH (μmol/g Hb) | No significant difference detected |

| [36] | BCC vs. control | Plasma | DTNB enzymatic recycling method following kit protocol from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) | GSH (µmol/mg protein) | Higher in BCC than control |

| [36] | BCC vs. medical history of NMSC (BCC) | Plasma | DTNB enzymatic recycling method following kit protocol from Sigma-Aldrich (MO, USA) | GSH (µmol/mg protein) | No significant difference detected |

| [40] | BCC vs. control | Erythrocytes | [41] | GSH (mg/dL) | Lower in BCC patients compared to control |

| [40] | BCC vs. AK | Erythrocytes | [41] | GSH (mg/dL) | Lower in BCC patients compared to AK |

| [5] | BCC vs. control | Plasma | [42] | TAC (mmol DPPH/L) | Lower in BCC patients than control |

| [5] | BCC vs. AK | Plasma | [42] | TAC (mmol DPPH/L) | No significant difference detected |

| [5] | BCC vs. SCC | Plasma | [42] | TAC (mmol DPPH/L) | No significant difference detected |

| [40] | BCC vs. control | Plasma | [43] | Ascorbic acid (mg/dL) | Lower in BCC patients compared to control |

| [40] | BCC vs. AK | Plasma | [43] | Ascorbic acid (mg/dL) | No significant difference detected |

| [40] | BCC vs. control | Plasma | [44] | a-tocopherol (mg/L) | Lower in BCC patients compared to control |

| [40] | BCC vs. AK | Plasma | [44] | a-tocopherol (mg/L) | Lower in BCC patients compared to AK |

| [45] | NMSC (BCC included) | Serum | [46] | Carotenoids (μmol/L) | No significant difference detected |

| [45] | NMSC (BCC included) | Serum | [46] | Selenium (μmol/L) | Lower in patients with NMSC |

| [45] | NMSC (BCC included) | Serum | [47] | a-tocopherol (μmol/L) | No significant difference detected |

| [48] | BCC vs. controls | Serum | [46] | Carotenoids (μmol/L) | No significant difference detected |

| [48] | BCC vs. controls | Serum | [46] | a-tocopherol (μmol/L) | No significant difference detected |

| [49] | BCC vs. controls | Serum | HPLC analysis (described in [50]) | a-tocopherol (μg/mL) | No significant difference detected |

| [49] | BCC vs. controls | Serum | HPLC analysis (described in [50]) | Retinol (μg/mL) | Lower in BCC patients than control |

| [51] | BCC vs. controls | Serum | [52] | Selenium (μg/dL) | No significant difference detected |

| [51] | BCC vs. controls | Serum | [53] | b-carotenoid (μg/dL) | No significant difference detected |

| [51] | BCC vs. controls | Serum | [53] | a-tocopherol (mg/dl) | No significant difference detected |

| [51] | BCC vs. controls | Serum | [53] | Retinol (μg/dL) | Higher in BCC patients compared to control |

| [54] | BCC vs. controls | Serum | Atomic absorption spectroscopy (AAS) | Zinc (μg/dL) | Lower in BCC than control |

| [40] | BCC vs. control | Plasma | [55] | Total thiol groups (mmol/L) | Lower in BCC patients compared to control |

| [40] | BCC vs. AK | Plasma | [55] | Total thiol groups (mmol/L) | No significant difference detected |

The micronutrient concentrations under comparison included ascorbic acid, selenium, carotenoids, vitamin E (a-tocopherol), vitamin A (retinol), and zinc. Ten of these indicated no statistical significance (Table 2). TAC assay is also included, as it refers to the cumulative action of several antioxidant components [35]. Other molecules with antioxidant capacities detected were glutathione (GSH) and total thiol groups, as plasma total sulfhydryl groups have also been suggested to contribute significantly to the antioxidant capacity of plasma [55]. Different results were observed concerning the same micronutrient marker, such as serum a-tocopherol in comparisons of BCC patients vs. controls. In total, no significant differences were found in 15 out of 28 comparisons.

Table 3.

Comparisons of markers of oxidative damage to proteins, lipids, or DNA detected in BCC patients compared with a study group.

Table 3.

Comparisons of markers of oxidative damage to proteins, lipids, or DNA detected in BCC patients compared with a study group.

| Study | Patients | Tested | Method Used | Redox Biomarker | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [5] | BCC vs. control | Plasma | [56] | TBARS (μmol/L) | Higher in BCC patients than control |

| [5] | BCC vs. control | Plasma | [57] | CARBS (nmol/mg protein) | No significant difference detected |

| [5] | BCC vs. AK | Plasma | [56] | TBARS (μmol/L) | No significant difference detected |

| [5] | BCC vs. AK | Plasma | [57] | CARBS (nmol/mg protein) | No significant difference detected |

| [5] | BCC vs. SCC | Plasma | [56] | TBARS (μmol/L) | No significant difference detected |

| [5] | BCC vs. SCC | Plasma | [57] | CARBS (nmol/mg protein) | Higher in SCC patients than BCC |

| [36] | BCC vs. controls | Urine | Competitive enzyme immunoassay (STA-320, Cell Biolabs, San Diego, CA, USA) | 8-oxo-dGuo levels (ng/mg creatinine) | Higher in BCC patients than control |

| [36] | BCC vs. medical history of NMSC (BCC) | Urine | Competitive enzyme immunoassay (STA-320, Cell Biolabs, San Diego, CA, USA) | 8-oxo-dGuo levels (ng/mg creatinine) | No significant difference detected |

| [58] | NMSC (BCC and SCC) vs. controls | Peripheral blood | [59] | H2O2-induced DNA damage (mean tail length after H2O2)—(basal mean tail length) | H2O2-induced DNA damage was significantly higher in NMSC (BCC and SCC) than in control |

| [54] | BCC vs. controls | Serum | Colorimetric assay, protocol kit by Sigma-Aldrich Company, catalog number MAK085 | MDA (nmol/mL) | Higher in BCC than control |

The impact of oxidative stress on DNA, lipids, and proteins in BCC patients was observed in four studies including 10 comparisons. Lipid byproducts in the studies were assessed in terms of TBARS and MDA and included four comparisons. DNA byproducts were expressed in urine 8-oxo-dGuo levels [36] and H2O2-induced DNA [58] damage, while protein oxidation was defined by CARBS (protein carbonyls) [5] (Table 3). No significant difference was detected in four out of ten comparisons.

Table 4.

Comparisons of enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidants as well as oxidative damage products present in SCC patients compared with a study group.

Table 4.

Comparisons of enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidants as well as oxidative damage products present in SCC patients compared with a study group.

| Study | Patients | Tested | Method Used | Redox Biomarker | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [5] | SCC vs. AK | Erythrocytes | [35] | GSH (μmol/g Hb) | No significant difference detected |

| [5] | SCC vs. AK | Erythrocytes | [35] | Catalase activity (U/mg Hb) | Lower in SCC patients than AK patients |

| [5] | SCC vs. AK | Plasma | [42] | TAC (mmol DPPH/L) | No significant difference detected |

| [5] | SCC vs. AK | Plasma | [56] | TBARS (μmol/L) | No significant difference detected |

| [5] | SCC vs. AK | Plasma | [57] | CARBS (nmol/mg protein) | Higher in SCC patients than AK patients |

| [5] | BCC vs. SCC | Erythrocytes | [35] | GSH (μmol/g Hb) | No significant difference detected |

| [5] | BCC vs. SCC | Erythrocytes | [35] | Catalase activity (U/mg Hb) | No significant difference detected |

| [5] | BCC vs. SCC | Plasma | [42] | TAC (mmol DPPH/L) | No significant difference detected |

| [5] | BCC vs. SCC | Plasma | [56] | TBARS (μmol/L) | No significant difference detected |

| [5] | BCC vs. SCC | Plasma | [57] | CARBS (nmol/mg protein) | Higher in SCC patients than BCC |

| [5] | SCC vs. control | Erythrocytes | [35] | GSH (μmol/g Hb) | No significant difference detected |

| [5] | SCC vs. control | Erythrocytes | [35] | Catalase (U/mg Hb) | Lower in SCC patients than control |

| [5] | SCC vs. control | Plasma | [42] | TAC (mmol DPPH/L) | Lower in SCC patients than control |

| [5] | SCC vs. control | Plasma | [56] | TBARS (μmol/L) | No significant difference detected |

| [5] | SCC vs. control | Plasma | [57] | CARBS (nmol/mg protein) | Higher in SCC patients than control |

| [58] | NMSC (BCC and SCC) vs. controls | Peripheral blood | [59] | H2O2-induced DNA damage (mean tail length after H2O2)—(basal mean tail length) | H2O2-induced DNA damage was significantly higher in NMSC (BCC and SCC) than in controls |

| [45] | NMSC (SCC included) | Serum | [46] | Carotenoids (μmol/L) | No significant difference detected |

| [45] | NMSC (SCC included) | Serum | [47] | Selenium (μmol/L) | Lower in patients with NMSC |

| [45] | NMSC (SCC included) | Serum | [46] | a-tocopherol (μmol/L) | No significant difference detected |

| [48] | SCC vs. controls | Serum | [46] | Carotenoids (μmol/L) | No significant difference detected |

| [48] | SCC vs. controls | Serum | [46] | a-tocopherol (μmol/L) | No significant difference detected |

| [51] | SCC vs. controls | Serum | [53] | Retinol (μg/dL) | No significant difference detected |

| [51] | SCC vs. controls | Serum | [53] | b-carotenoid (μg/dL) | No significant difference detected |

| [51] | SCC vs. controls | Serum | [53] | a-tocopherol (mg/dL) | No significant difference detected |

| [51] | SCC vs. controls | Serum | [52] | Selenium (μg/dL) | No significant difference detected |

| [60] | SCC vs. controls | Plasma | [61] | b-carotene (ng/mL) | No significant difference detected |

| [60] | SCC vs. controls | Plasma | [62] | a-tocopherol (μg/mL) | No significant difference detected |

| [60] | SCC vs. controls | Plasma | [62] | Retinol (ng/mL) | No significant difference detected |

| [60] | SCC vs. controls | Plasma | [63] | Selenium (ppm) | No significant difference detected |

SCC patients were examined in six studies [5,45,48,51,58,60] totaling 30 comparisons. SCC vs. controls were the most studied groups, featured in 14 comparisons [5]. Other comparisons involved SCC vs. BCC, SCC vs. AK, and SCC vs. medical history of NMSC. Among those comparisons, six reported enzymatic antioxidant mechanisms, seven discussed oxidative damage (oxidized products of lipids, proteins, and DNA), and seventeen evaluated antioxidant micronutrients. The oxidative biomarkers calculated were similar to those reported in BCC patients. Specifically, 20 of them showed no statistically significant differences; of these, most focused on micronutrients (Table 4) [47,49,59].

Table 5.

Comparisons of enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidants as well as oxidative damage products present in patients with medical history of NMSC.

Table 5.

Comparisons of enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidants as well as oxidative damage products present in patients with medical history of NMSC.

| Study | Patients | Tested | Method Used | Redox Biomarker | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [64] | Medical history of NMSC (BCC and SCC) vs. control | Plasma | [65] | TBARS (nmol/L) | No significant difference detected |

| [64] | Medical history of NMSC (BCC and SCC) vs. control | Plasma | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay-(Isoprostane Express EIA Kit; Cayman, USA) | 15-F2t-isoprostane levels (pg/mL) | Higher in NMSC-excised patients compared to control |

| [64] | Medical history of NMSC (BCC and SCC) vs. control | Plasma | [66] | Nitrate (mmol/L × 10−1) | No significant difference detected |

| [64] | Medical history of NMSC (BCC and SCC) vs. control | Plasma | Antioxidant Assay Kit protocol from Cayman, USA). | TAC (mmol × 10−2) | No significant difference detected |

| [36] | Medical history of NMSC (BCC) vs. control | Urine | Competitive enzyme immunoassay (STA-320, Cell Biolabs, San Diego, CA, USA) | 8-oxo-dGuo levels (ng/mg creatinine) | Higher in NMSC-excised patients than control |

| [36] | BCC vs. medical history of NMSC (BCC) | Urine | Competitive enzyme immunoassay (STA-320, Cell Biolabs, San Diego, CA, USA) | 8-oxo-dGuo levels (ng/mg creatinine) | No significant difference detected |

| [36] | Medical history of NMSC (BCC) vs. control | Plasma | Kit protocol from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI, USA) | Catalase Activity (unit/mg protein) | No significant difference detected |

| [36] | BCC vs. medical history of NMSC (BCC) | Plasma | Kit protocol from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI, USA) | Catalase Activity (unit/mg protein) | Lower in BCC patients than NMSC-excised patients |

| [36] | Medical history of NMSC (BCC) vs. control | Plasma | [37] | GPx (unit/mg protein) | No significant difference detected |

| [36] | BCC vs. medical history of NMSC (BCC) | Plasma | [37] | GPx (unit/mg protein) | Lower in BCC patients than NMSC-excised patients |

| [36] | Medical history of NMSC (BCC) vs. control | Plasma | [39] | NQO1 (µmol 2,6-dichloroindophenol reduced/min/mg protein) | No significant difference detected |

| [36] | BCC vs. medical history of NMSC (BCC) | Plasma | [39] | NQO1 (µmol 2,6-dichloroindophenol reduced/min/mg protein) | Lower in BCC patients than NMSC-excised patients |

| [36] | Medical history of NMSC (BCC) vs. control | Plasma | DTNB enzymatic recycling method following kit protocol from Sigma-Aldrich (St louis, MO, USA) | GSH (µmol/mg protein) | Higher in NMSC-excised than control |

| [36] | BCC vs. medical history of NMSC (BCC) | Plasma | DTNB enzymatic recycling method following kit protocol from Sigma-Aldrich (St louis, MO, USA) | GSH (µmol/mg protein) | No significant difference detected |

| [36] | Medical history of NMSC (BCC) vs. control | Plasma | [38] and kit protocol from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI, USA) | SOD (unit/mg protein) | Higher in NMSC-excised than control |

| [36] | BCC vs. medical history of NMSC (BCC) | Plasma | [38] and kit protocol from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI, USA) | SOD (unit/mg protein) | No significant difference detected |

| [67] | Medical history of NMSC (BCC and SCC) vs. control | Plasma | Protocol by Antioxidant Assay Kit (Cayman, USA). | TAC (nmol/L) | No significant difference detected |

| [68] | Medical history of NMSC (BCC) vs. control | Serum | [53] | Carotenoids | No significant difference detected |

| [68] | Medical history of NMSC (BCC) vs. control | Serum | [53] | a-tocopherol | No significant difference detected |

| [68] | Medical history of NMSC (BCC) vs. control | Serum | [52] | Selenium | No significant difference detected |

Patients with medical history of NMSC were also included in our review, as their exposure to extensive sunlight can lead to skin cancer development. However, they do not present with oxidative stress produced by cancer cells, since in these patients, the tumors are excised or treated with destructive methods. Regarding the outcomes, twenty-one comparisons were detected, of which nine focused on antioxidant enzymes, five on oxidized byproducts, and seven on antioxidant molecules (GSH and micronutrients) (Table 5). Interestingly, 13 of the 21 showed no differences, including 10 NMSC history–control comparisons, revealing that systemic oxidative stress parameters tend to resemble those of controls after skin cancer removal.

Concerning NMSC (BCC and SCC patients), most studies relied on their comparison with healthy controls, while only two of the studies compared NMSC with actinic keratosis patients [5,40]. Considering that those two groups have received the same external stressor, UV, the comparison of oxidative stress in these patients can be regarded as more trustworthy if the impact of oxidative stress on skin carcinogenesis is in question (see Table 1, Table 2 and Table 9). In view of the comparison of BCC vs. AK [5,40], one study indicated lower erythrocyte GSH levels in BCC patients, while another did not detect any differences regarding this biomarker. However, no changes were observed in any of the other examined parameters related to enzymatic mechanisms (catalase activity, etc.) or micronutrients (ascorbic acid, etc.). In the case of comparisons of BCC and controls, previous studies have examined eleven oxidative stress parameters in plasma, ten parameters in serum, and three in RBCs, compared to controls. Worth mentioning is that BCC patients presented significant alterations in redox biomarkers in plasma (10/11, 90.9%), whereas there were few differences in serum (4/10, 40%) and RBCs (2/3, 66%). This difference may be attributed to the fact that most studies on the serum of BCC patients were focused on micronutrients.

Regarding antioxidant enzyme activities in NMSC patients, the results seem scattered. Also, studies assessing postoperative oxidative stress modifications reveal a stress reduction that depends on the time of assessment as well as the therapeutic procedure, as chemotherapy is connected with a period of oxidative stress. Moreover, when assessing the differences between patients with BCC and patients with medical history of NMSC, the former displayed lower antioxidant enzyme activity regarding catalase, GPX, and NQO1, and no difference in SOD activity [Table 5].

In the case of comparisons between SCC patients and controls, seven oxidative stress markers were evaluated in plasma, six in serum, and two in RBCs. Interestingly, no serum antioxidant marker indicated any significant differences when compared to healthy individuals (Table 4).

Table 6.

Comparisons of enzymatic antioxidants retrieved from melanoma patients compared with a study group.

Table 6.

Comparisons of enzymatic antioxidants retrieved from melanoma patients compared with a study group.

| Study | Patients | Tested | Method Used | Redox Biomarker | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [69] | Melanoma patients vs. control | Serum | [70] | SOD (total superoxide dismutase activity) (U/mL) | Higher in melanoma (especially stage III) patients compared to control |

| [69] | Melanoma patients vs. control | Serum | [70] | Mn-SOD (U/mL) | Higher in melanoma (especially stage IV) patients compared to control |

| [69] | Melanoma patients vs. control | Serum | [71] | CAT (kU/L) | Higher in melanoma (especially stages I, II, and III) patients compared to control |

| [72] | Melanoma patients vs. control | Serum | [73] | Mn-SOD (ng/mL) | Higher in melanoma (all stages) patients compared to control |

| [74] | Melanoma patients vs. control | Erythrocytes | [75] | SOD (U/g Hb) | No significant difference detected |

| [74] | Melanoma patients vs. control | Erythrocytes | [71] | CAT (absorption/min/g Hb × 103) | No significant difference detected |

| [76] | Melanoma patients vs. control | Erythrocytes | [70] | SOD (U/g Hb) | Lower in melanoma patients compared to control |

| [76] | Melanoma patients vs. patients with excised melanoma | Erythrocytes | [70] | SOD (U/g Hb) | No significant difference detected |

| [76] | Melanoma patients vs. control | Erythrocytes | [77] | CAT (U/g Hb) | Higher in melanoma patients compared to control |

| [76] | Melanoma patients vs. patients with excised melanoma | Erythrocytes | [77] | CAT (U/g Hb) | No significant difference detected |

| [78] | Melanoma patients vs. control | Erythrocytes | [75] | CAT ((V abs/min) Hb−1) | Lower in melanoma patients compared to control |

| [78] | Melanoma patients vs. melanoma patients with metastasis | Erythrocytes | [75] | CAT ((V abs/min) Hb−1) | No significant difference detected |

| [78] | Melanoma patients with metastasis vs. controls | Erythrocytes | [75] | CAT ((V abs/min) Hb−1) | No significant difference detected |

| [78] | Melanoma patients vs. control | Erythrocytes | [75] | SOD (U/g Hb) | No significant difference detected |

| [78] | Melanoma patients vs. melanoma patients with metastasis | Erythrocytes | [75] | SOD (U/g Hb) | No significant difference detected |

| [78] | Melanoma patients with metastasis vs. control | Erythrocytes | [75] | SOD (U/g Hb) | No significant difference detected |

Melanoma patients were the subjects of sixteen comparisons, including with healthy individuals, between patients at different stages of the disease, and with patients with metastasis. Notably, oxidative stress parameters were influenced by the different stages of the disease. For example, serum total superoxide dismutase activity was higher in melanoma stage III patients compared to controls [69]. However, nine of those comparisons revealed no differences (Table 6).

Table 7.

Comparisons of non-enzymatic antioxidants, including metabolic antioxidants and dietary micronutrients, detected in melanoma patients.

Table 7.

Comparisons of non-enzymatic antioxidants, including metabolic antioxidants and dietary micronutrients, detected in melanoma patients.

| Study | Patients | Tested | Method Used | Redox Biomarker | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [74] | Melanoma patients vs. control | Erythrocytes | [79] | GSH (μM/g Hb−1) | Lower in melanoma patients compared to control |

| [72] | Melanoma patients vs. control | Erythrocytes | [79] | GSH (μΜ/g Hb) | Lower in melanoma patients compared to control |

| [72] | Melanoma patients vs. melanoma patients with metastasis | Erythrocytes | [79] | GSH (μΜ/g Hb) | No significant difference detected |

| [72] | Melanoma patients with metastasis vs. control | Erythrocytes | [79] | GSH (μΜ/g Hb) | No significant difference detected |

| [69] | Melanoma patients vs. control | Serum | [80] | Superoxide anion radical (mmol red nitroblue-tetrazolium/min/L) | Higher in all clinical stage melanoma patients compared to control |

| [81] | Melanoma patients vs. patients with excised melanoma | Serum | [82] | Albumin thiols (μmol/100 mL) | No significant difference detected |

| [74] | Melanoma patients vs. control | Plasma | [83] | Total thiols (μΜ) | Higher total thiols in melanoma patients compared to control |

| [79] | Melanoma patients vs. control | Plasma | [83] | Total thiols (μΜ) | No significant difference detected |

| [78] | Melanoma patients vs. melanoma patients with metastasis | Plasma | [83] | Total thiols (μΜ) | No significant difference detected |

| [78] | Melanoma patients with metastasis vs. control | Plasma | [83] | Total thiols (μΜ) | Higher in patients with melanoma metastasis compared to control |

| [78] | Melanoma patients vs. control | Plasma | [84] | TRAP (total radical-trapping antioxidant parameter) (μΜ Trolox) | No significant difference detected |

| [78] | Melanoma patients vs. melanoma patients with metastasis | Plasma | [84] | TRAP (total radical-trapping antioxidant parameter) (μΜ Trolox) | No significant difference detected |

| [78] | Melanoma patients with metastasis vs. control | Plasma | [84] | TRAP (total radical-trapping antioxidant parameter) (μΜ Trolox) | Higher in patients with melanoma metastasis compared to control |

| [81] | Melanoma patients vs. patients with excised melanoma | Serum | [85,86] | Serum antioxidants (μg/L) | No significant difference detected |

| [74] | Melanoma patients vs. control | Plasma | [87] | TRAP (total radical-trapping antioxidant parameter) (μΜ Trolox) | No significant difference detected |

| [88] | Melanoma patients | Serum | Mass spectrometry (ICP-MS NexION 350D, Perkin Elmer) | Selenium (µg/L) | A low selenium level might contribute to worse survival for patients with melanoma |

| [89] | Melanoma patients vs. control | Serum | Spectrometry | Selenium (μg/L) | All clinical melanoma stages (especially stage III) had lower selenium levels than the controls |

| [90] | Melanoma patients | Serum | Spectrometry | Selenium (μg/L) | Lower selenium correlates with worse disease severity |

| [90] | Melanoma patients | Serum | Spectrometry | Selenium (μg/L) | Selenium concentration was significantly lower for stage I and II melanomas with recurrence compared to those without recurrence |

| [51] | Melanoma patients vs. control | Serum | [53] | Retinol (μg/dL) | No significant difference detected |

| [51] | Melanoma patients vs. control | Serum | [53] | b-carotenoid (μg/dL) | No significant difference detected |

| [51] | Melanoma patients vs. control | Serum | [53] | a-tocopherol (mg/dl) | No significant difference detected |

| [51] | Melanoma patients vs. controls | Serum | [52] | Selenium (μg/dL) | No significant difference detected |

| [91] | Melanoma patients vs. control | Serum | Atomic absorption spectroscopy | Zinc (μg/100 mL) | No significant difference detected |

| [91] | Melanoma patients with metastasis vs. patients | Serum | Atomic absorption spectroscopy | Zinc (μg/100 mL) | No significant difference detected |

| [92] | Melanoma patients vs. control | Serum | [93] | Zinc (μg/100 mL) | Lower in melanoma patients compared to control |

| [94] | Melanoma patients vs. control | Serum | Atomic absorption spectroscopy | Zinc (μg/dL) | Higher in melanoma patients compared to control |

Table 8.

Comparisons of oxidative damage products present in melanoma patients compared to a study group.

Table 8.

Comparisons of oxidative damage products present in melanoma patients compared to a study group.

| Study | Patients | Tested | Method Used | Redox Biomarker | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [69] | Melanoma patients vs. control | Serum | [95] | mmol MDA/L | Higher in melanoma (especially stage IV) patients compared to control |

| [81] | Melanoma patients vs. patients with excised melanoma | Serum | [96] | Serum lipid peroxides (μmol/100 mL) | No significant difference detected |

| [74] | Melanoma patients vs. control | Plasma | [87] | MDA (nM) | Higher in melanoma patients compared to control |

| [76] | Melanoma patients vs. control | Plasma | [97] | MDA (μΜ) | Higher in melanoma patients compared to control |

| [76] | Melanoma patients vs. patients with excised melanoma | Plasma | [97] | MDA (μΜ) | Higher in melanoma patients compared to patients with melanoma history |

| [76] | Patients with excised melanoma vs. control | Plasma | [97] | MDA (μΜ) | No significant difference detected |

| [78] | Melanoma patients vs. control | Plasma | [98] | MDA (nM) | Higher in melanoma patients compared to control |

| [78] | Melanoma patients vs. melanoma patients with metastasis | Plasma | [98] | MDA (nM) | No significant difference detected |

| [78] | Melanoma patients with metastasis vs. control | Plasma | [98] | MDA (nM) | Higher in patients with melanoma history compared to control |

| [78] | Melanoma patients vs. control | Plasma | [99] | AOPPs (advanced oxidation protein products) (μΜ × mg protein) | No significant difference detected |

| [78] | Melanoma patients vs. melanoma patients with metastasis | Plasma | [99] | AOPPs (advanced oxidation protein products) (μΜ × mg protein) | No significant difference detected |

| [78] | Melanoma patients with metastasis vs. control | Plasma | [99] | AOPPs (advanced oxidation protein products) (μΜ × mg protein) | Higher in patients with melanoma metastasis compared to control |

The previous tables present comparisons of oxidative stress markers (oxidized protein and lipid products and vitamins). Superoxide anion radicals were considered an index of antioxidant defense, since their evaluation is based on a nitroblue–tetrazolium reduction [69]. Another significant antioxidant marker was the total radical-trapping antioxidant parameter (TRAP), based on the cumulative action of individual serum antioxidants such as uric acid, protein thiols, ascorbate, α-tocopherol, and bilirubin [78]. Interestingly, cancer stage and history of previous melanoma played a crucial role in the outcome of oxidative stress comparisons. No association was found in five of the twelve comparisons of oxidative damage markers, in ten of the seventeen comparisons of micronutrients, and in fifteen out of the twenty-eight comparisons of antioxidant molecules examined (Table 7 and Table 8).

Considering benign lesions, in our review, we included patients with AK and SK lesions. We found 25 comparisons of AK patients. By extending our research to SK, we also found two comparisons that reported no significant differences.

Table 9.

Comparisons of oxidative stress parameters present in patients with benign lesions (AK and SK).

Table 9.

Comparisons of oxidative stress parameters present in patients with benign lesions (AK and SK).

| Study | Patients | Tested | Method | Redox Biomarker | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [5] | AK vs. control | Erythrocytes | [35] | GSH (μmol/g Hb) | Lower in AK patients than control |

| [5] | AK vs. control | Erythrocytes | [35] | Catalase (U/mg Hb) | No significant difference detected |

| [5] | AK vs. control | Plasma | [42] | TAC (mmol DPPH/L) | No significant difference detected |

| [5] | AK vs. control | Plasma | [56] | TBARS (μmol/L) | Higher in AK patients than control |

| [5] | AK vs. control | Plasma | [57] | CARBS (nmol/mg protein) | No significant difference detected |

| [5] | SCC vs. AK | Erythrocytes | [35] | GSH (μmol/g Hb) | No significant difference detected |

| [5] | SCC vs. AK | Erythrocytes | [35] | Catalase activity (U/mg Hb) | Lower in SCC patients than AK patients |

| [5] | SCC vs. AK | Plasma | [42] | TAC (mmol DPPH/L) | No significant difference detected |

| [5] | SCC vs. AK | Plasma | [56] | TBARS (μmol/L) | No significant difference detected |

| [5] | SCC vs. AK | Plasma | [57] | CARBS (nmol/mg protein) | Higher in SCC patients than AK patients |

| [5] | BCC vs. AK | Erythrocytes | [35] | GSH (μmol/g Hb) | No significant difference detected |

| [5] | BCC vs. AK | Erythrocytes | [35] | Catalase (U/mg Hb) | No significant difference detected |

| [5] | BCC vs. AK | Plasma | [42] | TAC (mmol DPPH/L) | No significant difference detected |

| [5] | BCC vs. AK | Plasma | [56] | TBARS (μmol/L) | No significant difference detected |

| [5] | BCC vs. AK | Plasma | [57] | CARBS (nmol/mg protein) | No significant difference detected |

| [40] | BCC vs. AK | Plasma | [43] | Ascorbic acid (mg/dL) | No significant difference detected |

| [40] | BCC vs. AK | Plasma | [43] | a-tocopherol (mg/L) | Lower in BCC patients compared to AK |

| [40] | BCC vs. AK | Plasma | [57] | Total thiol groups (mmol/L) | No significant difference detected |

| [40] | BCC vs. AK | Erythrocytes | [41] | GSH (mg/dl) | Lower in BCC patients compared to AK |

| [40] | AK vs. control | Plasma | [49] | a-tocopherol (mg/L) | Lower in AK patients compared to control |

| [40] | AK vs. control | Plasma | [57] | Total thiol groups (mmol/L) | Lower in AK patients compared to control |

| [40] | AK vs. control | Plasma | [43] | Ascorbic acid (mg/dL) | Lower in AK patients compared to control |

| [40] | AK vs. control | Erythrocytes | [41] | GSH (mg/dL) | Lower in AK patients compared to control |

| [99] | SK vs. control | Plasma | TBARS, method not explained | MDA (mmol/L) | No significant difference detected |

| [99] | SK vs. control | Plasma | ELISA[100] | SOD (U/L) | No significant difference detected |

The following tables refer to the redox status of patients with common and recalcitrant warts (Table 10 and Table 11).

Table 10.

Comparisons of enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidants, as well as oxidative damage products, detected in patients with warts, including the type of wart (genital, etc.) and the number of lesions. The above-mentioned wart types are not recalcitrant (>36 months).

Table 10.

Comparisons of enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidants, as well as oxidative damage products, detected in patients with warts, including the type of wart (genital, etc.) and the number of lesions. The above-mentioned wart types are not recalcitrant (>36 months).

| Study | Patients | Tested | Number/Chronicity of the Lesions | Method Used | Redox Biomarker | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [101] | Patients with non-genital warts vs. control | Serum | NM/Most of the lesions occurred over 1 year (19.6 ± 3.8 months) | [102] | Disulfide (μm/L) | Higher in wart patients compared to control |

| [101] | Patients with non-genital warts vs. control | Serum | NM/Most of the lesions occurred over 1 year (19.6 ± 3.8 months) | [102] | Total serum thiol (μm/L) | Higher in wart patients compared to control |

| [101] | Patients with non-genital warts vs. control | Serum | NM/Most of the lesions occurred over 1 year (19.6 ± 3.8 months) | [102] | Disulfide/native thiol ratio | Higher in wart patients compared to control |

| [101] | Patients with non-genital warts vs. control | Serum | NM/Most of the lesions occurred over 1 year (19.6 ± 3.8 months) | [102] | Native thiol (µm/L) | No significant difference detected |

| [101] | Patients with non-genital warts vs. control | Serum | Genital (10 lesions) Non-genital (4 lesions)/Most of the lesions occurred over 1 year (19.35 ± 28.82 months) | [102] | Disulfide/total thiol | No significant difference detected |

| [101] | Patients with non-genital warts vs. control | Serum | Genital (10 lesions) Non-genital (4 lesions)/Most of the lesions occurred over 1 year (19.35 ± 28.82 months) | [102] | Native thiol/total thiol | No significant difference detected |

| [103] | Patients with genital and non-genital warts vs. controls | Serum | Genital (10 lesions) Non-genital (4 lesions)/Most of the lesions occurred over 1 year (19.35 ± 28.82 months) | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit (Human CoQ10-ELISA kit/Shanghai Sunred Biological Technology Co, Ltd., Shanghai, China) | Coenzyme Q10 levels (ng/mL) | No significant difference detected |

| [103] | Patients with genital and non-genital warts vs. controls | Serum | Genital (10 lesions) Non-genital (4 lesions)/Most of the lesions occurred over 1 year (19.35 ± 28.82 months) | Double heating method of Draper and Hadley [103] | MDA (µmol/L) | Higher in wart patients compared to control |

| [103] | Patients with genital and non-genital warts vs. controls | Serum | Genital (10 lesions) Non-genital (4 lesions)/Most of the lesions occurred over 1 year (19.35 ± 28.82 months) | Perkin Elmer AAnalyst 800 atomic absorption spectrometer (USA) with a deuterium background correction [104] | Zinc (µg/dL) | Lower in wart patients compared to control |

| [103] | Patients with genital vs. patients with non-genital warts | Serum | Genital (10 lesions) Non-genital (4 lesions)/Most of the lesions occurred over 1 year (19.35 ± 28.82 months) | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit (Human CoQ10-ELISA kit/Shanghai Sunred Biological Technology Co, Ltd., Shanghai, China) | Coenzyme Q10 levels (ng/mL) | No significant difference detected |

| [103] | Patients with genital vs. patients with non-genital warts | Serum | Genital (10 lesions) Non-genital (4 lesions)/Most of the lesions occurred over 1 year (19.35 ± 28.82 months) | Double heating method of Draper and Hadley [103] | MDA (µmol/L) | No significant difference detected |

| [103] | Patients with genital vs. patients with non-genital warts | Serum | Genital (10 lesions) Non-genital (4 lesions)/Most of the lesions occurred over 1 year (19.35 ± 28.82 months) | Perkin Elmer AAnalyst 800 atomic absorption spectrometer (USA) with a deuterium background correction [105] | Zinc (µg/dL) | No significant difference detected |

| [106] | Patients with non-genital warts vs. controls | Serum | From <5 to >10 lesions/Lesions occurred from <1 to >6 months | Spectrophotometric method (Randox reagents, HumaStar 300 analyzer) | Total oxidant status (µmol Trolox Eq/L) | Higher in wart patients compared to control |

| [106] | Patients with non-genital warts vs. controls | Serum | From <5 to >10 lesions/Lesions occurred from <1 to >6 months | Spectrophotometric method (Randox reagents, HumaStar 300 analyzer) | Total antioxidant status (µmol H2O2 Eq/L) | Lower in wart patients compared to control |

| [106] | Patients with non-genital warts vs. controls | Serum | From <5 to >10 lesions/Lesions occurred from <1 to >6 months | Spectrophotometric method (Randox reagents, HumaStar 300 analyzer) | Oxidative stress index (arbitrary units) | Higher in wart patients compared to control |

| [107] | Patients with genital or non-genital warts vs. controls | Serum | Non- recalcitrant warts (mean number of 5.5 lesions)/(Mean duration of 4.5 months) | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (Cayman, Canada, USA). | 8-hydroxy-2-deoxyguanosine (ng/mL) | No significant difference detected |

| [107] | Patients with genital or non-genital warts vs. controls | Serum | Non-recalcitrant warts (mean number of 5.5 lesions)/(Mean duration of 4.5 months) | [107] | Total oxidant status (µmol Trolox Eq/L) | No significant difference detected |

| [107] | Patients with genital or non-genital warts vs. controls | Serum | Non-recalcitrant warts (mean number of 5.5 lesions)/(Mean duration of 4.5 months) | [108] | Total antioxidant status (µmol H2O2 Eq/L) | No significant difference detected |

| [107] | Patients with genital or non-genital warts vs. controls | Serum | Non-recalcitrant warts (mean number of 5.5 lesions)/(Mean duration of 4.5 months) | [109] | Oxidative stress index (arbitrary units) | No significant difference detected |

| [107] | Patients with genital or non-genital warts vs. controls | Serum | Non-recalcitrant warts (mean number of 5.5 lesions)/(Mean duration of 4.5 months) | [102] | Total thiol (μmol/L) | Higher in wart patients compared to controls |

| [107] | Patients with genital or non-genital warts vs. controls | Serum | Non-recalcitrant warts (mean number of 5.5 lesions)/(Mean duration of 4.5 months) | [102] | Native thiol (μmol/L) | Higher in wart patients compared to controls |

| [107] | Patients with genital or non-genital warts vs. controls | Serum | Non-recalcitrant warts (mean number of 5.5 lesions)/(Mean duration of 4.5 months) | [102] | Disulphide (μmol/L) | Higher in wart patients compared to control |

| [107] | Patients with genital or non-genital warts vs. controls | Serum | Non-recalcitrant warts (mean number of 5.5 lesions)/(Mean duration of 4.5 months) | [102] | Native thiol/total thiol | Higher in wart patients compared to control |

| [107] | Patients with genital or non-genital warts vs. controls | Serum | Non-recalcitrant warts (mean number of 5.5 lesions)/(Mean duration of 4.5 months) | [102] | Disulphide/total thiol | Lower in wart patients compared to control |

| [107] | Patients with genital or non-genital warts vs. controls | Serum | NM/Most of the warts lasted less than 1 year | [102] | Disulphide/native thiol | Lower in wart patients compared to control |

| [110] | Patients with genital warts vs. controls | Serum | NM/Most of the warts lasted less than 1 year | [111] | Paraoxonase (ng/mL) | No significant difference detected |

| [110] | Patients with genital warts vs. controls | Erythrocytes | NM/Most of the warts lasted less than 1 year | [111] | GPx (IU/gHb) | Higher in wart patients compared to control |

| [110] | Patients with genital warts vs. controls | Serum | NM/Most of the warts lasted less than 1 year | High-pressure liquid chromatography via Chromsystems (Chromsystems®, Mannheim, Germany) kits and an Agilent 1200 series autoanalyzer (Agilent Technologies®, CA, USA). | MDA (mmol/L) | Higher in wart patients compared to control |

| [110] | Patients with genital warts vs. controls | Serum | NM/Most of the warts lasted less than 1 year | [111] | CAT (kU/L) | Higher in wart patients compared to control |

| [112] | Patients with non-genital warts vs. controls | Erythrocytes | 19 patients with less than 10 lesions and 12 patients with more than 10 lesions/Most of the warts lasted less than 1 year | [40] | CAT (U/g Hb) | Higher in wart patients compared to control |

| [112] | Patients with non-genital warts vs. controls | Erythrocytes | 19 patients with less than 10 lesions and 12 patients with more than 10 lesions/Most of the warts lasted less than 1 year | [40] | G6PD (U/g Hb) | Higher in wart patients compared to control |

| [112] | Patients with non-genital warts vs. controls | Erythrocytes | 19 patients with less than 10 lesions and 12 patients with more than 10 lesions/Most of the warts lasted less than 1 year | [113] | SOD (U/g Hb) | Higher in wart patients compared to control |

| [112] | Patients with non-genital warts vs. controls | Plasma | 19 patients with less than 10 lesions and 12 patients with more than 10 lesions/Most of the warts lasted less than 1 year | [114] | MDA (nmol/mL) | Higher in wart patients compared to control |

NM: not mentioned.

Table 11.

Comparisons of oxidative stress parameters in recalcitrant (>36 months) wart patients.

Table 11.

Comparisons of oxidative stress parameters in recalcitrant (>36 months) wart patients.

| Study | Patients | Tested | Method Used | Redox Biomarker | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [107] | Recalcitrant wart patients vs. control | Serum | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (Cayman, Canada, USA). | 8-hydroxy-2-deoxyguanosine (ng/mL) | Higher in recalcitrant patients compared to control |

| [107] | Recalcitrant wart patients vs. control | Serum | [107] | Total oxidant status (µmol Trolox Eq/L) | No significant difference detected |

| [107] | Recalcitrant wart patients vs. control | Serum | [108] | Total antioxidant status (µmol H2O2 Eq/L) | Higher in recalcitrant patients compared to control |

| [107] | Recalcitrant wart patients vs. control | Serum | [109] | Oxidative stress index (arbitrary units) | Higher in recalcitrant patients compared to control |

| [107] | Recalcitrant wart patients vs. control | Serum | [102] | Total thiol (μmol/L) | Higher in recalcitrant patients compared to control |

| [107] | Recalcitrant wart patients vs. control | Serum | [102] | Native thiol (μmol/L) | Higher in recalcitrant patients compared to control |

| [107] | Recalcitrant wart patients vs. control | Serum | [102] | Disulphide (μmol/L) | No significant difference detected |

| [107] | Recalcitrant wart patients vs. control | Serum | [102] | Native thiol/total thiol | Higher in recalcitrant patients compared to control |

| [107] | Recalcitrant wart patients vs. control | Serum | [102] | Disulphide/total thiol | Lower in recalcitrant patients compared to control |

| [107] | Recalcitrant wart patients vs. control | Serum | [102] | Disulphide/native thiol | Lower in recalcitrant patients compared to control |

| [107] | Recalcitrant wart patients vs. wart patients | Serum | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (Cayman, Canada, USA). | 8-hydroxy-2-deoxyguanosine (ng/mL) | No significant difference detected |

| [107] | Recalcitrant wart patients vs. wart patients | Serum | [107] | Total oxidant status (µmol Trolox Eq/L) | No significant difference detected |

| [107] | Recalcitrant wart patients vs. wart patients | Serum | [108] | Total antioxidant status (µmol H2O2 Eq/L) | No significant difference detected |

| [107] | Recalcitrant wart patients vs. wart patients | Serum | [109] | Oxidative stress index (arbitrary units) | No significant difference detected |

| [107] | Recalcitrant wart patients vs. wart patients | Serum | [102] | Total thiol (μmol/L) | Lower in recalcitrant wart patients compared with wart patients |

| [107] | Recalcitrant wart patients vs. wart patients | Serum | [102] | Native thiol (μmol/L) | Lower in recalcitrant wart patients compared with wart patients |

| [107] | Recalcitrant wart patients vs. wart patients | Serum | [102] | Disulphide (μmol/L) | Lower in recalcitrant wart patients compared with wart patients |

| [107] | Recalcitrant wart patients vs. wart patients | Serum | [102] | Native thiol/total thiol | No significant difference detected |

| [107] | Recalcitrant wart patients vs. wart patients | Serum | [102] | Disulphide/total thiol | No significant difference detected |

| [107] | Recalcitrant wart patients vs. wart patients | Serum | [102] | Disulphide/native thiol | No significant difference detected |

The measurement of dynamic thiol/disulfide (T/DS) homeostasis was used as a redox status biomarker. Thiols are proteins with organic sulfur compounds possessing antioxidant properties that operate through various mechanisms and fluctuations in dynamic disulfide bonds and are likely to be associated with oxidative stress levels [107]. Moreover, the oxidative stress index was estimated from the ratio of total antioxidant status to total oxidant status [107].

Differences between wart patients were observed to mainly depend on wart location (genital and non-genital) and their recalcitrant and non-recalcitrant state. Systemic oxidative stress parameters of recalcitrant wart patients were mainly evaluated in [107] (Table 11). Regarding the association of the number of warts with oxidative stress markers, the results are confusing, since some studies reported no association [110], while others displayed the opposite [103,107]. Regarding the comparisons of redox biomarkers, 19 differences were found, influenced mainly by the chronic nature of the disease and its recalcitrant nature. As for the comparison between recalcitrant and non-recalcitrant warts, no association was found in seven out of ten studies.

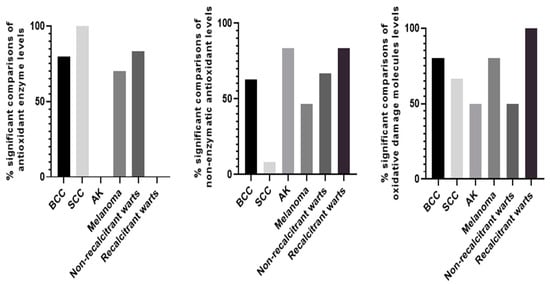

Given that, in general, the main interests of researchers lie in the comparison between control groups and skin diseases, we found 26 comparisons with BCC, 16 with SCC, 9 with AK, 30 with melanoma, 31 with warts, and 10 for recalcitrant warts, respectively. Among these comparisons, we excluded total oxidant and antioxidant status as well as the oxidation stress index as those markers belong to a specific redox biomarker category. The percentages of statistically significant and non-significant comparisons between patients and controls are indicated in Figure 1, with significant results proving that there is a difference in systemic oxidative stress parameters. Firstly, concerning antioxidant enzyme level comparisons, significant differences were found in 80% of BCC patients, 100% of SCC patients, 0% of AK patients, 70% of melanoma patients, 83.3% of non-recalcitrant wart patients, and 0% in recalcitrant wart patients when compared to controls. Secondly, when comparing non-enzymatic antioxidants between skin disease patients and controls, notable differences were observed in 62.5% of cases of BCC, 8.3% of SCC, 83.3% of AK, 46.7% of melanoma, 66.7% of non-recalcitrant warts, and 83.3% of recalcitrant warts. Finally, the respective percentages regarding differences in oxidative damage molecules are 80% for BCC, 66.7% for SCC, 50% for AK, 80% for melanoma, 50% for non-recalcitrant warts, and 100% for recalcitrant warts. Table 12 also summarizes statistically significant differences between controls and patients with malignant or benign lesions.

Figure 1.

Bar graphs illustrating % of statistically significant comparisons between disease and control groups in terms of antioxidant enzyme levels, non-enzymatic antioxidants, and oxidative damage molecules.

Table 12.

Summary of the results of statistically significant comparisons between controls and cases of malignant or benign lesions.

Table 12.

Summary of the results of statistically significant comparisons between controls and cases of malignant or benign lesions.

| Malignant | Benign | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BCC | Redox Biomarker Reported | Reference | Results | AK | Redox Biomarker Report | Reference | Results |

| Antioxidant enzyme levels | CAT | [36] | Lower | Non-enzymatic antioxidants | GSH | [5] | Lower |

| GPx | [36] | Lower | a-tocopherol | [40] | Lower | ||

| SOD | [36] | Higher | Total thiol groups | [40] | Lower | ||

| NQO1 | [36] | Lower | Ascorbic acid | [40] | Lower | ||

| Non-enzymatic antioxidants | GSH | [5] | Lower | GSH | [40] | Lower | |

| GSH | [36] | Higher | Oxidative damage molecules | TBARS | [5] | Higher | |

| GSH | [40] | Lower | Warts (non-recalcitrant) | ||||

| TAC | [5] | Lower | Antioxidant enzyme levels | GPx | [110] | Higher | |

| Ascorbic acid | [40] | Lower | CAT | [109] | Higher | ||

| a-tocopherol | [40] | Lower | CAT | [112] | Higher | ||

| Retinol | [48] | Lower | G6PD | [112] | Higher | ||

| Retinol | [50] | Higher | SOD | [112] | Higher | ||

| Total thiol groups | [40] | Lower | Non-enzymatic antioxidants | Disulfide | [101] | Higher | |

| Oxidative damage molecules | TBARS | [5] | Higher | Total serum thiol | [101] | Higher | |

| 8-oxo-dGuo levels | [36] | Higher | Disulfide/native thiol ratio | [101] | Higher | ||

| MDA | [53] | Higher | Zinc | [103] | Lower | ||

| SCC | Total thiol | [107] | Higher | ||||

| Antioxidant enzyme levels | CAT | [5] | Lower | Native thiol | [107] | Higher | |

| Non-enzymatic antioxidants | TAC | [5] | Lower | Disulphide | [107] | Higher | |

| Oxidative damage molecules | CARBS | [5] | Higher | Disulphide/total thiol | [107] | Higher | |

| H2O2-induced DNA damage | [58] | Higher | Disulphide/native thiol | [107] | Lower | ||

| Melanoma | Oxidative damage molecules | MDA | [103] | Higher | |||

| Antioxidant enzyme levels | SOD | [69] | Higher | MDA | [110] | Higher | |

| Mn-SOD | [69] | Higher | MDA | [72] | Higher | ||

| CAT | [69] | Higher | Recalcitrant warts | ||||

| Mn-SOD | [70] | Higher | Non-enzymatic antioxidants | Total thiol | [107] | Higher | |

| SOD | [77] | Lower | Native thiol | [107] | Higher | ||

| CAT | [77] | Higher | Native thiol/total thiol | [107] | Higher | ||

| CAT | [72] | Lower | Disulphide/total thiol | [107] | Higher | ||

| Non-enzymatic antioxidants | GSH | [74] | Lower | Disulphide/native thiol | [107] | Lower | |

| GSH | [72] | Lower | Oxidative damage molecules | 8-hydroxy-2-deoxyguanosine | [107] | Higher | |

| Total thiols | [74] | Higher | |||||

| Selenium | [89] | Lower | |||||

| Zinc | [92] | Lower | |||||

| Zinc | [94] | Higher | |||||

| Oxidative damage molecules | MDA | [69] | Higher | ||||

| MDA | [74] | Higher | |||||

| MDA | [75] | Higher | |||||

| MDA | [72] | Higher |

3. Discussion

In our review, we highlighted elevated levels of oxidative stress markers in patients with skin diseases, particularly NMSC, melanoma, and wart patients as well as patients with pre-malignant lesions such as AK, compared to healthy individuals. In the case of UV-related lesions, UV radiation, particularly UVA, can penetrate deep into the dermis and has the capacity to directly influence blood and lymph vessels [5,27]. Conversely, UVB radiation induces numerous direct photochemical alterations that lead skin cells to release cytokines and other signaling molecules. However, both UVA and UVB radiation induce an excess production of ROS within skin cells, inducing oxidative stress and its impact on DNA, proteins, and lipids.

The disruption of cellular metabolism within the skin, particularly through extracellular signaling, extend its effects to other tissues. Therefore, UVR plays a major role in systemic oxidative stress [27]. As a result, individuals with diseases related to UVR exposure such as skin cancer present altered systemic oxidative stress markers compared to controls [5]. The differences in redox status between BCC and SCC patients might be attributed to different exposure types. SCC is mostly associated with cumulative lifetime sun exposure, while intermittent and intense sun exposure is more related to the risk of BCC; in terms of oxidative stress, intense sun exposure can boost oxidative stress more than frequent stimuli [115]. Also, biomarkers of systemic oxidative stress correlate with human skin lightness levels, further complicating the correlation between UVR exposure and systemic oxidative stress [116]. The incidence of skin cancer in darker skin is greater, while systemic oxidative stress, even in individuals with skin of color, can contribute to the development of skin cancer when combined with other risk factors [20,117]. On the contrary, in pre-existing oxidative stress, a deficiency of antioxidant micronutrients is associated with compromised antioxidant capacity, enhancing to the vulnerability of the skin to oxidative stimuli like UV and subsequently to skin damage [118].

Systemic oxidative stress is a complex phenomenon, mediated by endogenous and/or exogenous triggers. Examined individuals vary in their susceptibility to oxidative damage due to genetic factors or lifestyle choices. For example, in [5], patients with vitamin D deficiency and NMSC revealed higher systemic oxidative stress parameters than controls, indicating the influence of environmental factor such as UV. Moreover, the involvement of oxidative stress in several pathological processes and diseases other than UVR-related disorders complicates the evaluation of systemic oxidative stress and its association with skin cancer even more. Therefore, increased redox biomarkers might reflect the outcome of co-morbidities. Indeed, high lipid peroxidation and ROS levels were detected in diabetic nephropathy patients. Increased levels of lipid oxidation have also been observed in obese patients with obstructive sleep apnea [119,120].

The complexity of oxidative stress can be further increased by the evaluation of redox biomarkers in various biological specimens like plasma and serum, which may affect the tested activity. Generally, plasma is considered to provide a more comprehensive view of the body’s antioxidant status compared to serum, as it reflects the antioxidant levels of all blood components. Nevertheless, the differences in antioxidant properties between plasma and serum are still ambiguous. Of note, a recent study revealed that plasma samples demonstrated greater resistance to oxidative stress, while serum exhibited a stronger ABTS cation radical-scavenging effect, probably attributed to serum proteins, including albumin. However, a previous investigation showed that TBARS levels in camels could be evaluated either in plasma or in serum, with no significant difference. The visible variations may result from methodological differences in the approaches used or the different organisms’ responses [121,122].