Quiet Quitting in Healthcare: The Synergistic Impact of Organizational Culture and Green Lean Six Sigma Practices on Employee Commitment and Satisfaction

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Quiet Quitting in Healthcare: Causes, Prevalence, and Impacts

2.2. Organizational Culture: The Role in Engagement, Motivation, and Retention

2.3. Lean Six Sigma (LSS) and Its Contribution to Healthcare

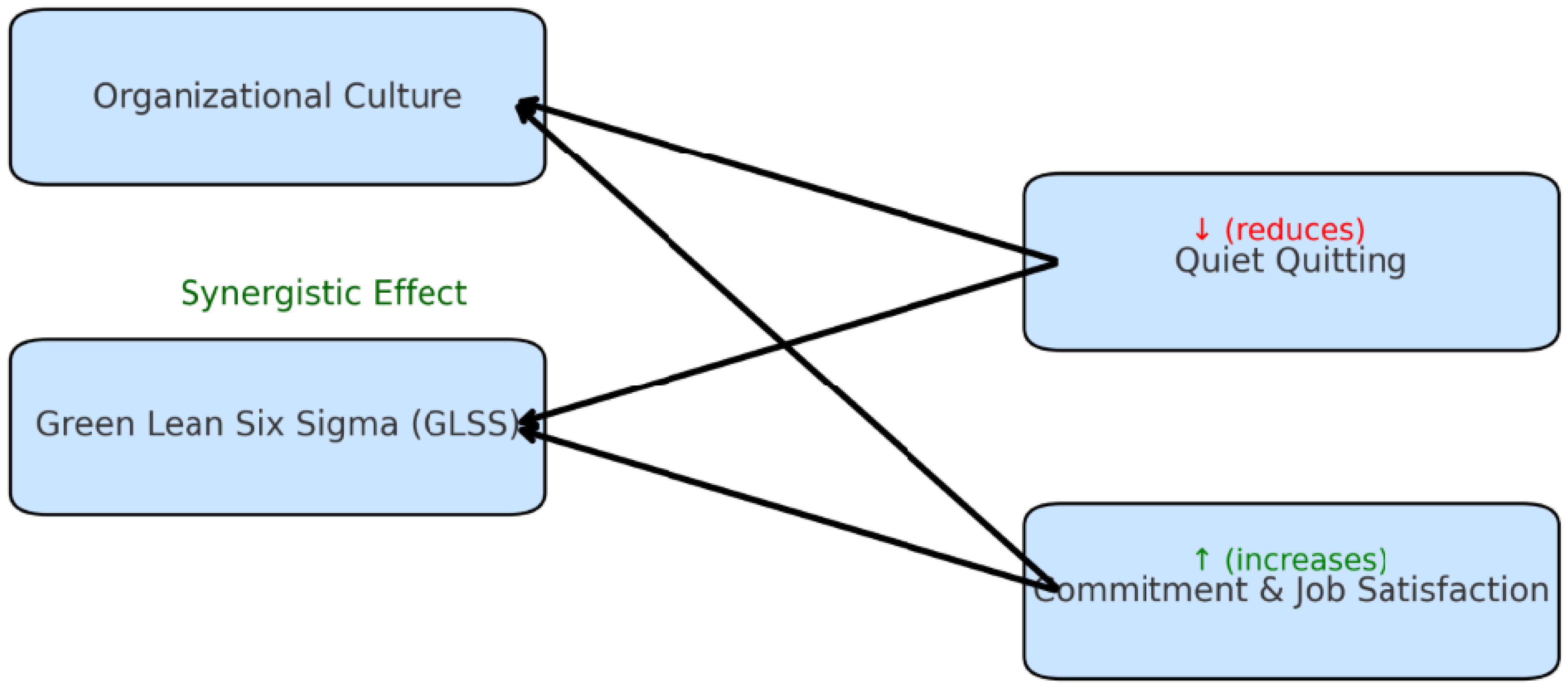

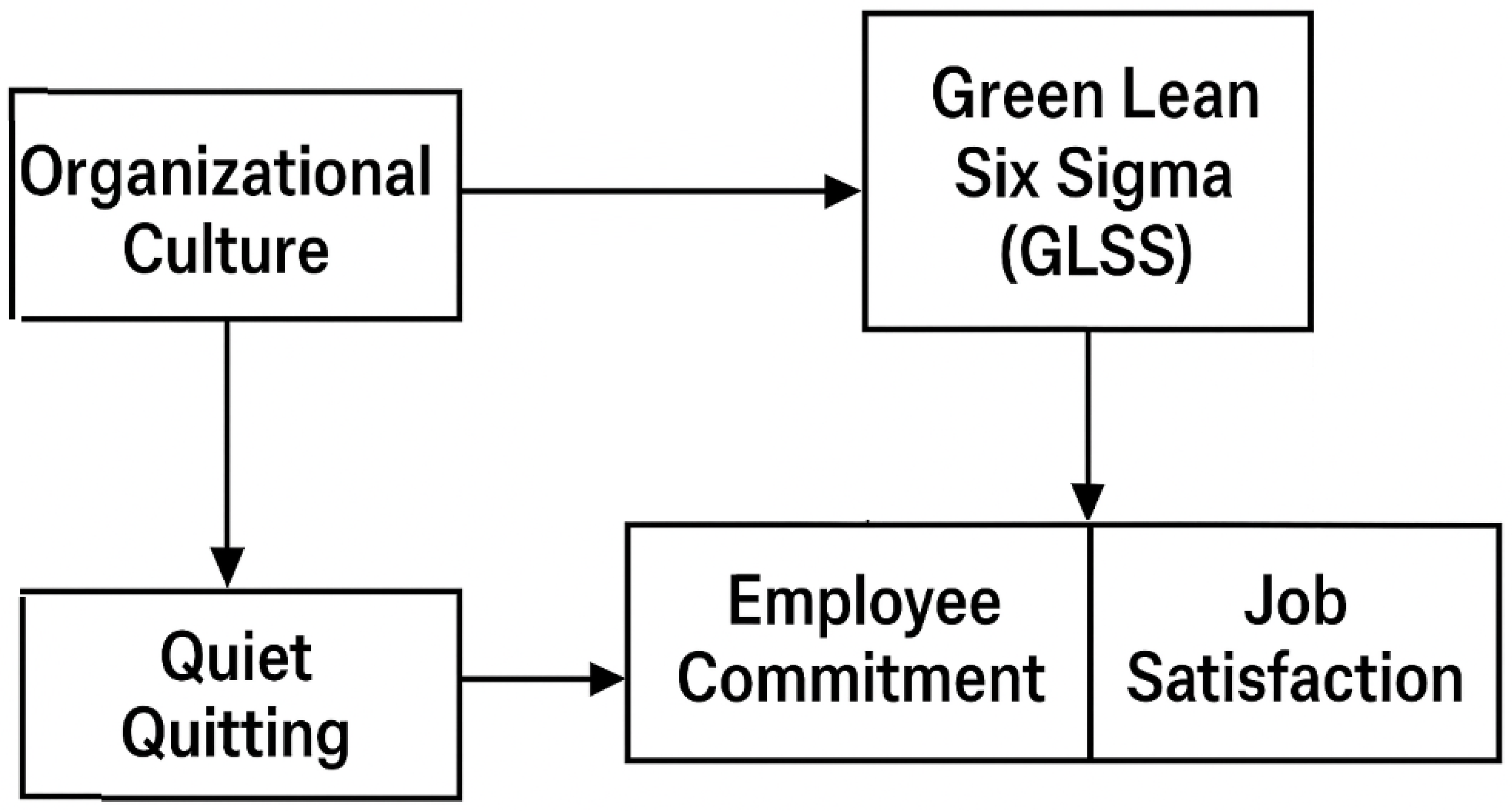

2.4. The Synergy of Culture and GLSS: An Integrated Framework

2.5. Conceptual Framework

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Population and Sample

3.3. Instrument Development

- Demographic Information: This section collected basic respondent data, including gender, age group, professional role, years of experience in healthcare, and the type of healthcare sector (public, private, NGO).

- Organizational Culture: A scale consisting of eight items measured respondents’ perceptions of organizational culture using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly Disagree, 5 = Strongly Agree). The questions focused on aspects such as leadership transparency, employee participation in decision-making, open communication, shared values, and a sense of belonging.

- Green Lean Six Sigma Practices: A six-item scale, also using a 5-point Likert scale, assessed the perceived application of process improvement methodologies, the integration of sustainability, waste reduction efforts, and staff involvement in continuous improvement initiatives.

- Quiet Quitting Indicators: This section utilized a seven-item scale to measure the presence of disengagement behaviors. Items were designed to capture reduced emotional investment, avoidance of extra responsibilities, lack of motivation, and performing only the minimum required.

- Commitment and Engagement: A six-item scale measured employee motivation and engagement, with questions addressing commitment to organizational success, trust in leadership, and pride in being part of the healthcare team.

- Organizational Support Against Disengagement: This final scale, comprising six items, evaluated the perceived organizational support mechanisms, such as early burnout identification, mental well-being support, work–life balance, and management responsiveness to staff concerns.

3.4. Validity and Reliability

3.5. Data Collection and Ethical Considerations

3.6. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Respondent Demographic Profile

4.2. Descriptive Statistics and Scale Reliability

4.3. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

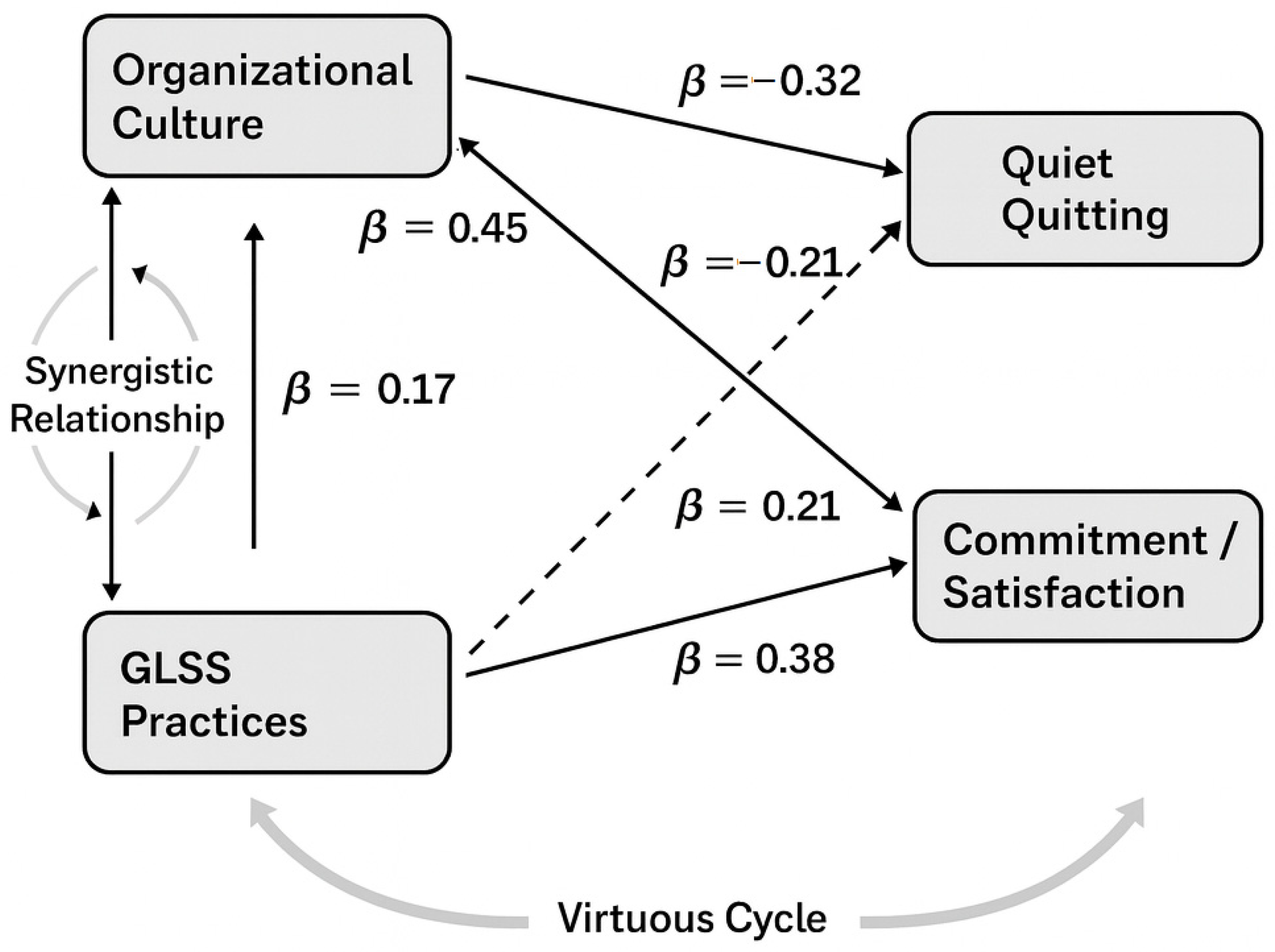

4.4. Hypothesis Testing: SEM

5. Discussion

5.1. Interpretation of Key Findings and Alignment with Literature

5.2. The Synergistic Effect of Culture and GLSS: A Virtuous Cycle of Improvement

5.3. Visualizing the Synergy Between Organizational Culture and GLSS

5.4. Practical Implications for Healthcare Administrators and Business Leaders

- Strengthen cultural foundations before or alongside GLSS initiatives through transparent leadership and active staff engagement.

- Adopt participatory GLSS practices that empower employees to co-design process improvements.

- Embed sustainability metrics into improvement programs to align efficiency with environmental and ethical goals.

- Create interdisciplinary “green lean” teams to promote collaboration and innovation.

- Conduct regular cultural assessments to detect risks such as toxic supervision or disengagement.

- Invest in ethical and environmental training that integrates professional purpose with organizational strategy.

5.5. Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GLSS | Green Lean Six Sigma |

| LSS | Lean Six Sigma |

| SEM | Structural Equation Modeling |

Appendix A

- Gender: ☐ Female ☐ Male ☐ Other ☐ Prefer not to say

- Age Group: ☐ 18–30 ☐ 31–40 ☐ 41–50 ☐ 51–60 ☐ 61+ ☐ Prefer not to say

- Professional Role: ☐ Clinical Staff ☐ Administrative Staff ☐ Managerial Staff ☐ Other: _______

- Years of Experience in Healthcare: ☐ 0–4 ☐ 5–10 ☐ 11–20 ☐ 21–30 ☐ 31+ ☐ Prefer not to say

- Healthcare Sector: ☐ Public ☐ Private ☐ NGO ☐ Other: _______

- Leadership in my organization operates with transparency and integrity.

- Employees participate actively in decision-making processes.

- Open communication between departments is consistently encouraged.

- The organization promotes shared values and teamwork.

- New staff are smoothly integrated into the organizational culture.

- I feel a strong sense of belonging within the organization.

- Feedback and continuous improvement are core values in my workplace.

- Personal values are aligned with the organization’s mission and culture.

- My organization applies process improvement methodologies such as Lean or Six Sigma.

- Sustainability is considered in day-to-day healthcare operations.

- Waste reduction and efficiency are prioritized through structured initiatives.

- Staff are trained and involved in continuous improvement practices.

- GLSS initiatives have improved my workflow or reduced unnecessary tasks.

- The organization regularly evaluates and adjusts its processes based on employee feedback.

- I feel less emotionally invested in my work than before.

- I avoid taking on responsibilities outside my basic job description.

- I often think of leaving but don’t express it.

- I am disengaged during meetings or organizational activities.

- I rarely contribute ideas even when I have suggestions.

- I perform only the minimum required to meet job expectations.

- My work-related motivation has significantly decreased in recent months.

- I feel committed to the success of this organization.

- I trust the decisions made by leadership.

- I would recommend this healthcare facility as a good place to work.

- My work is appreciated and recognized.

- I see a future for myself in this organization.

- I am proud to be part of this healthcare team.

- The organization identifies and addresses employee burnout early.

- Support mechanisms are in place for mental well-being.

- There is a good balance between work and personal life.

- Management listens and responds to staff concerns.

- GLSS practices empower me to stay engaged and proactive.

- The workplace promotes innovation and self-improvement.

Appendix B

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Organizational Culture | 1.00 | |||

| 2. GLSS Practices | 0.62 *** | 1.00 | ||

| 3. Quiet Quitting | −0.55 *** | −0.48 *** | 1.00 | |

| 4. Commitment/Satisfaction | 0.78 *** | 0.65 *** | −0.61 *** | 1.00 |

| Index | Value | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| χ2 | 485.67 | The model has a significant difference from the perfect model, which is common in large samples. |

| Degrees of Freedom (df) | 345 | |

| p-value | <0.001 | |

| Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) | 0.048 | Good fit (values < 0.05 are excellent, <0.08 are acceptable) |

| Comparative FitIndex (CFI) | 0.94 | Good fit (values > 0.90 are acceptable, >0.95 are excellent) |

| Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) | 0.045 | Good fit (values < 0.08 are generally considered a good fit) |

| Path | Unstandardized Coef. (B) | Standard Error (SE) | Standardized Coef. (β) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quiet Quitting <- Organizational Culture | −0.36 | 0.05 | −0.32 | <0.001 |

| Quiet Quitting <- GLSS Practices | −0.21 | 0.04 | −0.21 | <0.01 |

| Commitment/Satisfaction <- Organizational Culture | 0.52 | 0.06 | 0.45 | <0.001 |

| Commitment/Satisfaction <- GLSS Practices | 0.41 | 0.05 | 0.38 | <0.001 |

| Indirect Path | Unstandardized Coef. (B) | Standard Error (SE) | Standardized Coef. (β) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organizational Culture -> GLSS Practices -> Commitment/Satisfaction | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.17 | <0.05 |

References

- Agris, J. L., Gelmon, S., Wynia, M. K., Buder, B., Emma, K. J., Alasmar, A., & Frankel, R. (2024). How leaders at high-performing healthcare organizations think about organizational professionalism. Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics, 52(4), 922–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alquwez, N. (2023). Association between nurses’ experiences of workplace incivility and the culture of safety of hospitals: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 32(1–2), 320–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarado-Ramírez, K. M., Pumisacho-Álvaro, V. H., Miguel-Davila, J. Á., & Suárez Barraza, M. F. (2018). Kaizen, a continuous improvement practice in organizations: A comparative study in companies from Mexico and Ecuador. TQM Journal, 30(4), 255–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anokha, V., & Reddy, A. V. (2025). Beyond the paycheck: Unlocking employee engagement. In R. Garg (Ed.), Harnessing happiness and wisdom for organizational well-being (pp. 61–84). IGI Global. [Google Scholar]

- Antony, J., Lancastle, J., McDermott, O., Bhat, S., Parida, R., & Cudney, E. A. (2023). An evaluation of Lean and Six Sigma methodologies in the national health service. International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management, 40(1), 25–52. [Google Scholar]

- Atiq, A., Sullman, M., & Apostolou, M. (2025). The silent shift: Exploring the phenomenon of quiet quitting in modern workplaces. Personnel Review, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydın, B. (2018). The role of organizational culture on leadership styles. Manas Journal of Social Studies, 7(1), 267–280. [Google Scholar]

- Banaszak-Holl, J., Castle, N. G., Lin, M. K., Shrivastwa, N., & Spreitzer, G. (2015). The role of organizational culture in retaining nursing workforce. The Gerontologist, 55(3), 462–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourke, C., Mulaniff, A., Tang, B., Waya, O., & Teeling, S. P. (2024). Using a person-centred model of Lean Six Sigma to support process improvement within a paediatric primary eye care clinic. Research Square. preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boy, Y., & Sürmeli, M. (2023). Quiet quitting: A significant risk for global healthcare. Journal of Global Health, 13, 03014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brubakk, K., Svendsen, M. V., Deilkås, E. T., Hofoss, D., Barach, P., & Tjomsland, O. (2021). Hospital work environments affect the patient safety climate: A longitudinal follow-up using a logistic regression analysis model. PLoS ONE, 16(10), e0258471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capolupo, N., Rosa, A., & Adinolfi, P. (2024). The liaison between performance, strategic knowledge management, and lean six sigma: Insights from healthcare organizations. Knowledge Management Research & Practice, 22(3), 314–326. [Google Scholar]

- Carney, M. (2011). Influence of organizational culture on quality healthcare delivery. International Journal of Health Care Quality Assurance, 24(7), 523–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chugani, N., Kumar, V., Garza-Reyes, J. A., Rocha-Lona, L., & Upadhyay, A. (2017). Investigating the green impact of Lean, Six Sigma and Lean Six Sigma: A systematic literature review. International Journal of Lean Six Sigma, 8(1), 7–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clery, P., d’Arch Smith, S., Marsden, O., & Leedham-Green, K. (2021). Sustainability in quality improvement (SusQI): A case study in undergraduate medical education. BMC Medical Education, 21(1), 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, V. (2016). Correlation and regression. In A. R. Rao, & K. H. Hamed (Eds.), Fundamentals of statistical hydrology (pp. 391–440). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Crocker, D. A. (2008). Ethics of global development: Agency, capability, and deliberative democracy. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cronley, C., & Kim, Y. (2017). Intentions to turnover: Testing the moderated effects of organizational culture, as mediated by job satisfaction, within the Salvation Army. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 38(2), 194–209. [Google Scholar]

- Dekker, S., Oates, A., & Rafferty, J. (Eds.). (2022). Restorative just culture in practice: Implementation and evaluation. CRC Press. [Google Scholar]

- dos Santos, N. R., & Pais, L. (2025). Decent work, human needs, demands, and resources. In Decent work-life-flow and organizational sustainability: Achieving balance, health, and performance in organizations (pp. 31–56). Springer Nature. [Google Scholar]

- Erdil, N. O., Aktas, C. B., & Arani, O. M. (2018). Embedding sustainability in lean six sigma efforts. Journal of Cleaner Production, 198, 520–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukami, T. (2024). Enhancing healthcare accountability for administrators: Fostering transparency for patient safety and quality enhancement. Cureus, 16(8), e66007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanis, P., Katsiroumpa, A., Vraka, I., Siskou, O., Konstantakopoulou, O., Katsoulas, T., Moisoglou, I., Gallos, P., & Kaitelidou, D. (2024). Nurses quietly quit their job more often than other healthcare workers: An alarming issue for healthcare services. International Nursing Review, 71(4), 850–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galvan, M. C., & Pyrczak, F. (2023). Writing empirical research reports: A basic guide for students of the social and behavioral sciences. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Gholami, H., Jamil, N., Mat Saman, M. Z., Streimikiene, D., Sharif, S., & Zakuan, N. (2021). The application of green lean six sigma. Business Strategy and the Environment, 30(4), 1913–1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graban, M. (2018). Lean hospitals: Improving quality, patient safety, and employee engagement (3rd ed.). Productivity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gün, İ., Balsak, H., & Ayhan, F. (2025). Mediating effect of job burnout on the relationship between organisational support and quiet quitting in nurses. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 81(8), 4644–4652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harhash, D., Ahmed, M. Z., & Elshereif, H. (2020). Healthcare organizational culture: A concept analysis. Menoufia Nursing Journal, 5(1), 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- How, M. L., & Cheah, S. M. (2023). Business renaissance: Opportunities and challenges at the dawn of the quantum computing era. Businesses, 3(4), 585–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoxha, G., Simeli, I., Theocharis, D., Vasileiou, A., & Tsekouropoulos, G. (2024). Sustainable healthcare quality and job satisfaction through organizational culture: Approaches and outcomes. Sustainability, 16(9), 3603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, M., Pavlova, M., Ghalwash, M., & Groot, W. (2021). The impact of hospital accreditation on the quality of healthcare: A systematic literature review. BMC Health Services Research, 21(1), 1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igoe, A., O’Connor, A., O’Reilly, A., Tobin, A. M., & Bourke, J. F. (2024). Implementing person-centred Lean Six Sigma to transform dermatology waiting lists: A case study from a major teaching hospital in Dublin, Ireland. Science, 6(4), 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilangakoon, T. S., Weerabahu, S. K., Samaranayake, P., & Wickramarachchi, R. (2022). Adoption of Industry 4.0 and lean concepts in hospitals for healthcare operational performance improvement. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 71(6), 2188–2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, A., Sato, K., Yumoto, Y., Sasaki, M., & Ogata, Y. (2022). A concept analysis of psychological safety: Further understanding for application to health care. Nursing Open, 9(1), 467–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jekiel, C. M. (2020). Lean human resources: Redesigning HR processes for a culture of continuous improvement. Productivity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kakouris, A., Athanasiadis, V., & Sfakianaki, E. (2025a). Industry 4.0 and lean thinking: The critical success factors perspective. International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management, 42(6), 1625–1671. [Google Scholar]

- Kakouris, A., Sfakianaki, E., & Kapaj, M. (2025b). Lean readiness factors for higher education. International Journal of Lean Six Sigma, 16(3), 752–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakouris, A., Sfakianaki, E., & Tsioufis, M. (2022). Lean thinking in lean times for education. Annals of Operations Research, 316(1), 657–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H., & Ahn, J. W. (2021). Model setting and interpretation of results in research using structural equation modeling: A checklist with guiding questions for reporting. Asian Nursing Research, 15(3), 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, J., Kim, H., & Cho, O. H. (2023). Quiet quitting among healthcare professionals in hospital environments: A concept analysis and scoping review protocol. BMJ Open, 13(11), e077811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaper, M. S., Sixsmith, J., Koot, J. A., Meijering, L. B., van Twillert, S., Giammarchi, C., Bevilacqua, R., Barry, M. M., Doyle, P., Reijneveld, S. A., & de Winter, A. F. (2018). Developing and pilot testing a comprehensive health literacy communication training for health professionals in three European countries. Patient Education and Counseling, 101(1), 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kargas, A. D., & Varoutas, D. (2015). On the relation between organizational culture and leadership: An empirical analysis. Cogent Business & Management, 2(1), 1055953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaswan, M. S., & Rathi, R. (2020). Green Lean Six Sigma for sustainable development: Integration and framework. Environmental Impact Assessment Review, 83, 106396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaswan, M. S., Rathi, R., Antony, J., Cross, J., Garza-Reyes, J. A., Singh, M., Preet Singh, I., & Sony, M. (2024). Integrated Green Lean Six Sigma-Industry 4.0 approach to combat COVID-19: From literature review to framework development. International Journal of Lean Six Sigma, 15(1), 50–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsiroumpa, A., Moisoglou, I., Konstantakopoulou, O., Kalogeropoulou, M., Gallos, P., Tsiachri, M., & Galanis, P. (2024). Practice environment scale of the nursing work index (5 items version): Translation and validation in Greek. International Journal of Caring Sciences, 17(3), 1509. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R. B. (2023). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (5th ed.). Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Knapp, S. (2015). Lean Six Sigma implementation and organizational culture. International Journal of Health Care Quality Assurance, 28(8), 855–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubiak, T. M., & Benbow, D. W. (2016). The certified six sigma black belt handbook. Quality Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kyriakeli, G., Georgiadou, A., Lithoxopoulou, M., Tsimtsiou, Z., & Kotsis, V. (2025a). The impact of ISO certification procedures on patient safety culture in public hospital departments. Healthcare, 13(6), 661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriakeli, G., Georgiadou, A., Symeonidou, A., Tsimtsiou, Z., Dardavesis, T., & Kotsis, V. (2025b). Patient safety culture among nurses in hospital settings worldwide: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety, 51(5), 350–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C. Y., & Huang, C. K. (2021). Employee turnover intentions and job performance from a planned change: The effects of an organizational learning culture and job satisfaction. International Journal of Manpower, 42(3), 409–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, R. F., Buljac-Samardžić, M., Akdemir, N., Hilders, C., & Scheele, F. (2020). What do we really assess with organisational culture tools in healthcare? An interpretive systematic umbrella review of tools in healthcare. BMJ Open Quality, 9(1), e000826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marsden, O., Clery, P., D’Arch Smith, S., & Leedham-Green, K. (2021). Sustainability in quality improvement (SusQI): Challenges and strategies for translating undergraduate learning into clinical practice. BMC Medical Education, 21(1), 555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDermott, O., Antony, J., Bhat, S., Jayaraman, R., Rosa, A., Marolla, G., & Parida, R. (2022a). Lean six sigma in healthcare: A systematic literature review on challenges, organisational readiness and critical success factors. Processes, 10(10), 1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermott, O., Antony, J., Douglas, J., Antony, F., & Sony, M. (2022b). Lean Six Sigma in healthcare: A systematic literature review on motivations and benefits. Processes, 10(10), 1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirji, H., Bhavsar, D., & Kapoor, R. (2023). Impact of organizational culture on employee engagement and effectiveness. American Journal of Economics and Business Management, 6(1), 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Moisoglou, I., Katsiroumpa, A., Katsapi, A., Konstantakopoulou, O., & Galanis, P. (2025). Poor nurses’ work environment increases quiet quitting and reduces work engagement: A cross-sectional study in Greece. Nursing Reports, 15(1), 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortimer, F., Isherwood, J., Wilkinson, A., & Vaux, E. (2018). Sustainability in quality improvement: Redefining value. Future Healthcare Journal, 5(2), 88–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, R. O., & Hancock, G. R. (2018). Structural equation modeling. In The reviewer’s guide to quantitative methods in the social sciences (pp. 445–456). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima, H., & Sekiguchi, T. (2025). Is business planning useful for entrepreneurs? A review and recommendations. Businesses, 5(1), 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardi, P. M. (2018). Doing survey research: A guide to quantitative methods (4th ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, I. K., Goh, W. G., Thong, C., & Teo, K. S. (2025). ‘Quiet quitting’ among medical practitioners: A hallmark of burnout, disillusionment and cynicism. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 118(3), 73–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuru, H. A. (2024). Leadership Strategies for Sustainable Organizational Performance in Small and Medium Healthcare Businesses [Doctoral dissertation, Walden University]. [Google Scholar]

- Patyal, V. S., & Koilakuntla, M. (2018). Impact of organizational culture on quality management practices: An empirical investigation. Benchmarking: An International Journal, 25(5), 1406–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pevec, N. (2023). The concept of identifying factors of quiet quitting in organizations: An integrative literature review. Challenges of the Future/IzziviPrihodnosti, 8(2), 128–147. [Google Scholar]

- Poku, C. A., Bayuo, J., Agyare, V. A., Sarkodie, N. K., & Bam, V. (2025). Work engagement, resilience and turnover intentions among nurses: A mediation analysis. BMC Health Services Research, 25(1), 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rathi, R., Kaswan, M. S., Antony, J., Cross, J., Garza-Reyes, J. A., & Furterer, S. L. (2023). Success factors for the adoption of green lean six sigma in healthcare facility: An ISM-MICMAC study. International Journal of Lean Six Sigma, 14(4), 864–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizos, S., Sfakianaki, E., & Kakouris, A. (2022). Quality of administrative services in higher education. European Journal of Educational Management, 5(2), 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romosiou, V., Brouzos, A., & Vassilopoulos, S. P. (2019). An integrative group intervention for the enhancement of emotional intelligence, empathy, resilience and stress management among police officers. Police Practice and Research, 20(5), 460–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudnick, J. D., Jr., Jaeger, C. L., Kenly, B. N., Modafari, N. M., & Saraswat, J. (2023). Evaluation cases frame healthcare quality improvement. In Handbook of research on quality and competitiveness in the healthcare services sector (pp. 37–62). IGI Global. [Google Scholar]

- Rushton, C. H., & Sharma, M. (2018). Designing sustainable systems for ethical practice. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schrepp, M. (2015). User experience questionnaire handbook: All you need to know to apply the UEQ successfully in your project. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Martin-Schrepp/publication/303880829_User_Experience_Questionnaire_Handbook_Version_2/links/575a631b08ae414b8e460625/User-Experience-Questionnaire-Handbook-Version-2.pdf (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- Sen, L., Kumar, A., & Biswal, S. K. (2023). An inferential response of organizational culture upon human capital development: A justification on the healthcare service sector. Folia Oeconomica Stetinensia, 23(1), 208–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sfakianaki, E., & Kakouris, A. (2019). Lean thinking for education: Development and validation of an instrument. International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management, 36(6), 917–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sijm-Eeken, M., Greif, A., Peute, L., & Jaspers, M. (2024). Implementation of Green Lean Six Sigma in Dutch healthcare: A qualitative study of healthcare professionals’ experiences. Nursing Reports, 14(4), 2877–2895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simeli, I., Tsekouropoulos, G., Vasileiou, A., & Hoxha, G. (2023). Benefits and challenges of teleworking for a sustainable future: Knowledge gained through experience in the era of COVID-19. Sustainability, 15(15), 11794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohal, A., Prajapati, S., Morrison, J., & Hilton, K. (2022). Success factors for lean six sigma projects in healthcare. Journal of Management Control, 33(2), 215–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockemer, D., Stockemer, G., & Glaeser, J. (2019). Quantitative methods for the social sciences. Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J., Sarfraz, M., Ivascu, L., & Ozturk, I. (2023). How does organizational culture affect employees’ mental health during COVID-19? The mediating role of transparent communication. Work, 76(2), 473–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swarnakar, V., Bagherian, A., & Singh, A. R. (2021). Modeling critical success factors for sustainable LSS implementation in hospitals: An empirical study. International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management, 39(5), 1249–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şen, H. (2025). A systematic review of quiet quitting in the health sector. OPUS Journal of Society Research, 22(3), 391–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teeling, S. P., Dewing, J., & Baldie, D. (2021). A realist inquiry to identify the contribution of Lean Six Sigma to person-centred care and cultures. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(19), 10427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theocharis, D. (2025). Peer dynamics in digital marketing: How product type shapes the path to purchase among Gen Z consumers. Businesses, 5(3), 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toska, A., Dimitriadou, I., Togas, C., Nikolopoulou, E., Fradelos, E. C., Papathanasiou, I. V., Sarafis, P., Malliarou, M., & Saridi, M. (2025). Quiet quitting in the hospital context: Investigating conflicts, organizational support, and professional engagement in Greece. Nursing Reports, 15(2), 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsekouropoulos, G., Vasileiou, A., Hoxha, G., Dimitriadis, A., & Zervas, I. (2024). Sustainable approaches to medical tourism: Strategies for Central Macedonia/Greece. Sustainability, 16(1), 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsekouropoulos, G., Vasileiou, A., Hoxha, G., Theocharis, D., Theodoridou, E., & Grigoriadis, T. (2025). Leadership 4.0: Navigating the challenges of the digital transformation in healthcare and beyond. Administrative Sciences, 15(6), 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasileiou, A., Sfakianaki, E., & Tsekouropoulos, G. (2024). Exploring sustainability and efficiency improvements in healthcare: A qualitative study. Sustainability, 16(19), 8306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veseli, A., Hasanaj, P., & Bajraktari, A. (2025). Perceptions of organizational change readiness for sustainable digital transformation: Insights from learning management system projects in higher education institutions. Sustainability, 17(2), 619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westland, J. C. (2015). Structural equation models. Studies in Systems, Decision and Control, 22(5), 152. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav, V., Kumar, V., Gahlot, P., Mittal, A., Kaswan, M. S., Garza-Reyes, J. A., Rathi, R., Antony, J., Kumar, A., & Owad, A. A. (2024). Exploration and mitigation of green lean six sigma barriers: A higher education institutions perspective. TQM Journal, 36(7), 2132–2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y., Jensen, J. M., & Jørgensen, R. H. (2025). On the factors influencing banking satisfaction and loyalty: Evidence from Denmark. Businesses, 5(2), 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P., Zhang, H., & Wang, A. (2025). Research on the impact of hospital organizational behavior on physicians’ patient-centered care. Archives of Public Health, 83(1), 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Q., Johnson, S., & Sarkis, J. (2018). Lean Six Sigma and environmental sustainability: A hospital perspective. Supply Chain Forum: An International Journal, 19(1), 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zu, X., Fredendall, L. D., & Douglas, T. J. (2008). The evolving theory of quality management: The role of Six Sigma. Journal of Operations Management, 26(5), 630–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Category | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 215 | 68.9% |

| Male | 97 | 31.1% | |

| Age Group | 18–30 | 38 | 12.2% |

| 31–40 | 129 | 41.3% | |

| 41–50 | 85 | 27.2% | |

| 51–60 | 50 | 16.0% | |

| 61+ | 10 | 3.2% | |

| Professional Role | Clinical Staff | 175 | 56.1% |

| Administrative Staff | 90 | 28.9% | |

| Managerial Staff | 47 | 15.0% | |

| Years of Experience | 0–4 | 25 | 8.0% |

| 5–10 | 78 | 25.0% | |

| 11–20 | 170 | 54.5% | |

| 21–30 | 32 | 10.3% | |

| 31+ | 7 | 2.2% | |

| Healthcare Sector | Public | 222 | 71.1% |

| Private | 80 | 25.6% | |

| NGO | 10 | 3.3% |

| Scale | Items | Mean (M) | Standard Deviation (SD) | Cronbach’s Alpha (α) | Composite Reliability (CR) | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organizational Culture | 8 | 3.82 | 0.65 | 0.91 | 0.93 | 0.62 |

| Green Lean Six Sigma Practices | 6 | 3.24 | 0.81 | 0.88 | 0.90 | 0.60 |

| Quiet Quitting Indicators | 7 | 2.45 | 0.77 | 0.89 | 0.89 | 0.53 |

| Commitment and Engagement | 6 | 4.10 | 0.58 | 0.92 | 0.91 | 0.63 |

| Path | Standardized Coefficient (β) | 95% Confidence Interval | p-Value | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organizational Culture → Quiet Quitting | −0.32 | [−0.42, −0.22] | <0.001 | Supported (H1) |

| GLSS Practices → Quiet Quitting | −0.21 | [−0.29, −0.13] | <0.01 | Supported (H2) |

| Organizational Culture → Commitment/Satisfaction | 0.45 | [0.33, 0.57] | <0.001 | Supported (H3) |

| GLSS Practices → Commitment/Satisfaction | 0.38 | [0.28, 0.48] | <0.001 | Supported (H4) |

| Organizational Culture → GLSS Practices → Commitment/Satisfaction (Indirect) | 0.17 | [0.09, 0.25] | <0.05 | Supported (H5) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vasileiou, A.; Tsekouropoulos, G.; Hoxha, G.; Theocharis, D.; Grigoriadis, E. Quiet Quitting in Healthcare: The Synergistic Impact of Organizational Culture and Green Lean Six Sigma Practices on Employee Commitment and Satisfaction. Businesses 2025, 5, 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/businesses5040057

Vasileiou A, Tsekouropoulos G, Hoxha G, Theocharis D, Grigoriadis E. Quiet Quitting in Healthcare: The Synergistic Impact of Organizational Culture and Green Lean Six Sigma Practices on Employee Commitment and Satisfaction. Businesses. 2025; 5(4):57. https://doi.org/10.3390/businesses5040057

Chicago/Turabian StyleVasileiou, Anastasia, Georgios Tsekouropoulos, Greta Hoxha, Dimitrios Theocharis, and Evangelos Grigoriadis. 2025. "Quiet Quitting in Healthcare: The Synergistic Impact of Organizational Culture and Green Lean Six Sigma Practices on Employee Commitment and Satisfaction" Businesses 5, no. 4: 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/businesses5040057

APA StyleVasileiou, A., Tsekouropoulos, G., Hoxha, G., Theocharis, D., & Grigoriadis, E. (2025). Quiet Quitting in Healthcare: The Synergistic Impact of Organizational Culture and Green Lean Six Sigma Practices on Employee Commitment and Satisfaction. Businesses, 5(4), 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/businesses5040057