1. Introduction

The relationship between materialism and pro-environmental tendencies remains complex and contested. Meta-analytic evidence (

Hurst et al., 2013) demonstrates a generally negative association between materialism and both pro-environmental attitudes and behaviors. However, more recent studies have reported weaker or even reversed effects under certain contexts (e.g.,

Evers et al., 2018;

Kuanr et al., 2020;

Islam et al., 2022). This variability suggests that, while materialism is a relatively stable human trait, contextual, social, and identity-related factors may influence whether materialistic consumers engage in pro-environmental choices. As an explanation,

Hurst et al. (

2013) propose that environmental issues became globally acknowledged to such a degree that even materialists find it hard to question those problems when reporting their attitudes. Therefore, it is not surprising that the latest studies began to call into question the prevailing notion of incompatibility between materialism and pro-environment tendencies.

However, emerging evidence suggests that this relationship is more nuanced than previously assumed. Several studies have reported conditions under which materialistic individuals may demonstrate pro-environmental choices, often driven by identity-related motives and social reputation concerns. For example,

Evers et al. (

2018) found that materialism can positively influence sustainable consumption when environmentally friendly behaviors offer opportunities for innovative product usage.

Nepomuceno and Laroche (

2015) demonstrated that individuals, regardless of their materialistic orientation, may resist consumption when their long-term goals and self-control are activated. Similarly,

Islam et al. (

2022) highlighted how materialism, combined with face consciousness, can promote sustainable luxury consumption when environmentally responsible choices enhance social status or emotional rewards.

Similarly, consumers with a strong positive global cultural identity were found to be exhibiting high materialism and environmentally friendly tendencies simultaneously (

Strizhakova & Coulter, 2013). Moreover, evidence from the study of

Kuanr et al. (

2020) has confirmed a direct and positive relationship between materialism and voluntary simplicity attitudes when environmental degradation interferes with their well-being. Hence, the simultaneous endorsement of materialistic values and environmentally friendly tendencies seems plausible to assume. In other words, these findings suggest that pro-environmental behavior among materialistic consumers may arise when such actions serve ego-enhancing or identity-affirming purposes. Since materialists are highly sensitive to social judgments and are merely driven by extrinsic motivation, their desire for social approval presumably may translate into pro-environmental behavior when the latter prevails among significant others and has the potential to improve reputation. Even if not in line with materialistic values, such a response might be personally rewarding. It may help establish the desirable social standing and social acceptance by signifying that person is environmentally cautious, caring, or generous. For example,

Griskevicius et al. (

2010) found that under conditions of high social visibility, consumers’ willingness to buy green products is determined by the need to signal their relatively higher status. Therefore, it follows that purely egoistic self-interest can induce pro-environment behavioral tendencies (

Griskevicius et al., 2012). This dynamic illustrates that egoistic motives—rather than altruistic values—can still drive pro-environmental actions when doing so aligns with symbolic identity expression or reputational benefits.

Further, being high on materialism does not negate the desire to look like a non-materialistic person. According to

Tatzel (

2003), hidden materialists try to associate themselves with various pro-environment movements such as voluntary simplicity to reconcile materialistic values with non-materialism. However,

Tatzel (

2003) notes that materialists’ appreciation for social status and a constant feeling of insufficiency reveals that they merely strive to justify their expensive acquisitions. Moreover, pro-environmental behavior does not make people morally sound and does not necessarily spill over to the other domains in the same ethical manner. For example,

Mazar and Zhong (

2010) found that purchasing green products boost the sense of moral self, which subsequently may be perceived as permitting and justifying socially unacceptable behavior in the other domains of life. Evolutionary theory suggests that people are inclined to imitate the behavior of significant others regardless of whether those actions are environmentally friendly or not (

Griskevicius et al., 2012).

Furthermore,

Goenka and Thomas (

2020) revealed that conspicuous consumption might be morally acceptable if it signals the social identity characteristics compatible with the binding values. The binding morality emphasizes purity, patriotism, and loyalty to the group and puts group interests above individualistic concerns. Binding values tie people and maintain the existence of such social entities as families and nations. Individuals willing to self-sacrifice and adhere to in-group values are rewarded with respect (

Napier & Luguri, 2013).

Pro-environmental behavior becomes socially desirable on a global scale and demands certain compromises for the in-group benefit. Pro-environmentalists are associated with positive personality traits and the upper half of social class (

Gifford & Nilsson, 2014). Because materialists have a strong desire to comply with the group and be socially approved, they may find it appealing to behave pro-environmentally. An evolutionary perspective suggests that reputational concern is a powerful predictor of willingness to self-sacrifice (

Griskevicius et al., 2012). Therefore, materialists concerned about reputation may be willing to adopt pro-environmental behavior intentionally. The belief in the power of pro-environmental behavior to enhance the desirable self more effectively may outweigh the desire for possessions if the latter fails to affirm the preferred identity. Since possessions and acquisitions provide only symbolic value and are favored to the degree, they can ensure success and happiness, it seems plausible to expect that such instrumental means can be easily replaceable. For example, the negative correlation between materialistic success and personal debt suggests that success may be equalized to the ability not to get into debt (

Nepomuceno & Laroche, 2015). Therefore, if restricted consumption, non-consumption, or downsized consumption and other forms of pro-environmental behavior are identity-relevant, materialists might consider such behavior a proper way to satisfy identity-related needs. If, for example, specific consumption patterns hold favorable symbolic meaning, materialists might include those patterns into their self-image by signaling who they are to their significant others.

The above reasoning explains the inconsistency of findings on materialism–pro-environmental behavior linkage. The less negative association between materialism and pro-environmental attitude, but not behavior, observed in recent publications

Hurst et al. (

2013), demonstrates the phenomenon known as a pro-environmental attitude–behavior gap. The sensitivity to prosocial reputation can motivate materialists to behave more environmentally friendly in public, even if they place a relatively minor emphasis on the environmentalism value (

Wang et al., 2019).

Dîrțu and Prundeanu (

2023) provides updated insights by showing that both grandiose and vulnerable narcissism diminish individuals’ perceived environmental control, while grandiose narcissism additionally predicts lower pro-environmental attitudes and behaviors. These findings highlight the role of personality-driven self-enhancement motives and sensitivity to social evaluation in shaping environmentally relevant decisions. Complementing this perspective,

Kesenheimer and Greitemeyer (

2021) conducted a longitudinal study capturing changes in materialism and pro-environmental behavior during the COVID-19 lockdown. Their results reveal that both materialism values and pro-environmental behaviors declined temporarily under societal restrictions; however, pro-environmental attitudes consistently predicted lower materialism levels across all time points, while narcissistic traits amplified materialistic orientations, especially after restrictions were lifted. Together, these findings extend the conclusions of

Hurst et al. (

2013) by demonstrating that the materialism–pro-environmental outcome link is influenced not only by stable value orientations but also by psychological traits and situational forces, underscoring the importance of considering identity-driven motives and social context in understanding pro-environmental decision-making.

The prevalent consumer culture, which cultivates self-enhancement values on the one hand and social pressure to comply with pro-environmental norms on the other, necessitates consumers to make trade-offs. Though previous research acknowledges and addresses numerous situational and personality-related factors responsible for the attitude–behavior gap, relatively little is known about the necessity of making trade-offs between conflicting preferences. This study contributes to the body of knowledge by examining how consumers make decisions when they must choose between materialistic and pro-environmental preferences. In response to the recent call for a better understanding of the attitude–behavior gap, the present study employs two methodologies (conjoint and self-reported measures) to determine the extent to which consumers’ choices are consistent with their self-reported values and habitual behavior. In addition, on the basis of prior research indicating that narcissism as a personality trait is susceptible to positive self-bias and overestimation of personal skills and qualities (

Nehrlich et al., 2019), the current study tests the hypothesis that narcissism is responsible for the self-reported attitude–behavior gap. Specifically, we hypothesize that consumers high in narcissism should exhibit a larger gap between attitude and behavior.

While the narrative examples often reference green product choices or consumption—consistent with the marketing context and materialism literature—this study adopts a broader definition of pro-environmental behavior. Specifically, we incorporate

Markle’s (

2013) multidimensional framework that includes environmental citizenship, conservation, food, and transportation preferences.

The objective of this study is to examine how materialism and pro-environmental values influence consumer choice, and whether narcissism moderates the alignment between self-reported values and preferences. To explore this, we test three hypotheses that capture the associations and moderating effects between these psychological traits and pro-environmental decision-making.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. First, we present the theoretical background and hypotheses development and the conceptual model. Next, we describe the methodology, including the conjoint design, scales, and data collection process. Then, the results of the study are reported and discussed in relation to existing literature. Finally, we conclude by outlining theoretical and practical implications, as well as limitations and directions for future research. Last, but not least, this article is a revised and expanded version of a paper titled “Trade-offs between materialism and pro-environmental behavior in the light of narcissism”, which was presented at EMAC Regional 2022 conference in Kaunas, Lithuania, 2022 September 21–23.

3. Hypothesis

Previous literature has consistently documented a negative relationship between materialism and pro-environmental behavior (PEB). Materialistic individuals prioritize acquisition and extrinsic goals, often at the expense of environmental concern (

Hurst et al., 2013;

Richins & Dawson, 1992). Materialism is associated with self-centered values, reduced empathy for collective well-being, and greater environmental disregard (

Kilbourne & Pickett, 2008). Accordingly, we expect that individuals with stronger materialistic orientations will show lower tendencies toward pro-environmental behavior.

H1. Materialism is negatively associated with pro-environmental behavior.

However, recent research suggests that value–behavior associations are not always straightforward. The attitude–behavior gap (

Kollmuss & Agyeman, 2002) and dual-attitude models (

Wilson et al., 2000) propose that explicit self-reported attitudes may not consistently predict real-world choices, especially when moderated by personality traits or contextual cues.

One such trait is narcissism, which has been shown to influence both materialism and PEB. Narcissistic individuals tend to emphasize self-enhancement, image management, and social dominance (

Campbell & Foster, 2011). Narcissism has been identified as a predictor of materialism (

Rose, 2007) and also relates to pro-environmental behavior—but often in complex, context-dependent ways (

Bergman et al., 2014). For example, narcissists may support sustainability when it enhances their image (

Griskevicius et al., 2010), but may overstate their green values while failing to act on them.

Because narcissistic individuals are often positively biased in self-reporting, striving to present themselves favorably (

Paulhus, 1984), we expect a weaker correspondence between stated values and observed preferences—a gap that may be especially evident in domains linked to image or morality.

H2. At higher levels of narcissism, the association between material preferences and reported material values should be weaker.

Similarly, we anticipate that narcissism will moderate the alignment between pro-environmental attitudes and behavior. While narcissists may endorse PEB in self-report measures, their choices may not reflect these attitudes due to impression-management motives or limited intrinsic concern for sustainability.

H3. At higher levels of narcissism, the association between pro-environmental behavior preferences and reported pro-environmental behavior attitudes should be weaker.

By testing these hypotheses, the study aims to advance understanding of how materialism and narcissism jointly shape the value–behavior alignment in the sustainability domain, contributing to research on personality-driven gaps and the motivational complexity behind green consumer behavior.

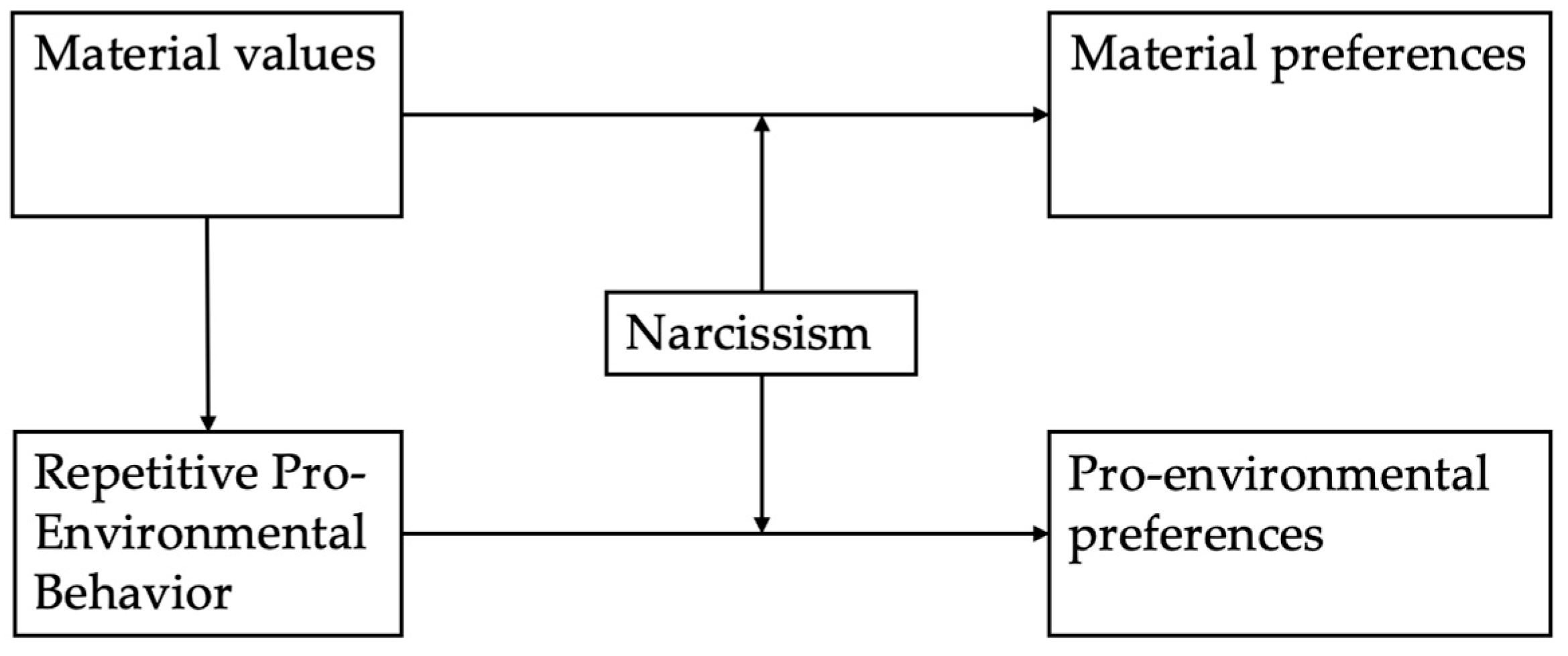

The conceptual model (see

Figure 1) visualizes the hypothesized relationships between material values, pro-environmental behavior, narcissism, and individual preferences. Material values are expected to influence both expressed material preferences and repetitive pro-environmental behavior. Narcissism is positioned as a moderating factor that may affect the congruence between self-reported values and choice-based preferences. Specifically, narcissism is assumed to weaken the alignment between material values and material preferences, and between pro-environmental behavioral tendencies and actual pro-environmental preferences. This structure reflects a dual-attitude framework, suggesting that the gap between values and behavior may be systematically shaped by personality traits such as narcissism.

4. Materials and Methods

A convenience sample of 71 participants who volunteered to participate in the experiment via an online platform Conjoint.ly (

Trochim & Donnelly, 2022) was employed. Conjoint analysis was selected because it allows us to measure trade-offs between competing attributes when individuals make multi-attribute decisions (

P. E. Green & Srinivasan, 1990). The within-subject design of the conjoint task allowed each participant to evaluate between 6 and 14 choice sets, resulting in a large number of total observations. Respondents were contacted via social networks and the university’s mailing list in Lithuania. Participants ranged in age from 21 to 57 years, with a mean age of 32.6. 65% of the respondents who took part were women, 34% were men, and 1% did not indicate their sex. Respondents’ education background was 3% secondary education, 6% trade school education, 6%—not finished higher education, 7% active higher education students, and 78% higher education. Participation was voluntary and anonymous.

The experiment was carried out through a conjoint.ly platform. Prior to the conjoint task, a manipulation check was used to ensure participants fully understood the attribute dimensions. Each participant answered short comprehension questions regarding the difference between attribute levels (e.g., “Which option represents a prestigious brand?”). If responses indicated misunderstanding, participants were automatically screened out by the Conjoint.ly platform, and their data excluded from further analysis. Respondents who passed the manipulation check moved to the conjoint exercise. After finishing the conjoint exercise, participants were exposed to Material Value Scale, Recurring Pro-Environmental Behavior Scale, and Narcissistic Admiration and Rivalry Questionnaire short scale. At the end of the experiment, respondents were asked to provide age, sex, and educational background-related information.

Materialism dimensions for conjoint analysis were re-adjusted to be comparable with the material value scale. The centrality dimension was expressed through monetary value, where respondents were given to choose between low value and high-value sums of money. The success dimension was represented by prestige, where respondents were given to make a choice between casual and prestigious brands. The happiness dimension was illustrated through tangibility, where respondents needed to choose between the same value purchase, of which one was experiential and another material (

Zarco, 2014). Pro-environmental behavior attributes matched with the corresponding dimensions of the pro-environmental behavior scale (

Markle, 2013). In designing the conjoint attributes and levels, our aim was to capture the entire range of potential value-driven trade-offs. Specifically, the materialism-related attributes and levels were structured to span the continuum from non-materialistic orientations to highly materialistic tendencies, while the pro-environmental behavior attributes and levels covered the range from anti-environmental preferences to strongly pro-environmental choices. This approach allowed us to examine how consumers balance competing motives across the full spectrum of relevant decision contexts. A summary of attributes and levels is presented below in

Table 1.

Participants were asked questions about each dimension level during a manipulation check to determine whether they clearly understood the difference between concepts. In case of incorrect answers, respondents’ participation in the experiment was terminated.

The conjoint design-related algorithm randomly generated 6 to 14 choice sets of two combinations, consisting of three materialism dimensions: monetary value, prestige, tangibility attributes, and one pro-environmental behavior dimension. Respondents were supposed to make a decision about which choice set is more acceptable and select it.

Concerning attitudinal measurement, materialism was measured using Material Values Scale developed by

Richins (

2004). Material Values Scale is a seven-point Likert-type instrument aimed at measuring materialism centrality (7 items), happiness (5 items), and success (6 items) dimensions, where 1 is “strongly disagree,” and 7—“strongly agree.”

Pro-environmental behavior was measured by employing the Recurring Pro-Environmental Behavior Scale developed by

Brick et al. (

2017). Scale is a five-point Likert-type instrument to measure pro-environmental behavior as a one-dimensional construct with 21 items, where 1 is “very rarely” and 5—is “very often.” This scale, per all items, unifies dimensions such as conservation, ecological citizenship, food, and transport.

Narcissism was measured through the Narcissistic Admiration and Rivalry Questionnaire short scale (NARQ-S) developed by

Leckelt et al. (

2018). Scale is a six-point Likert-type instrument to measure dimensions such as rivalry (3 items) and admiration (3 items), where 1 is “strongly disagree,” and 6—is “strongly agree.” For moderation analysis, narcissism was dichotomized using a median split, creating two groups: high and low narcissism. All measurement items are presented in

Table A1 in the

Appendix A. Normality of scale variables was tested using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Based on these results, Pearson correlations were reported for normally distributed pairs of variables, and Spearman correlations were used otherwise.

In this study, the value–behavior gap was operationalized as the discrepancy between participants’ self-reported values (measured via validated scales on materialism and pro-environmental behavior) and their revealed preferences captured through the conjoint experiment. Specifically, we assessed whether individuals with higher self-reported pro-environmental attitudes or lower materialism scores still favored profile choices inconsistent with those values, thereby indicating an attitude–behavior gap.

5. Results

The conjoint analysis revealed the respondents’ preferences across different attributes, as presented in

Table 2. The highest preference was observed for pro-environmental behavior attributes. Specifically,

growing forest received the strongest average preference score (0.343), while its opposing level,

tree logs, received a negative score (−0.137). Similarly, for transportation,

bicycle (0.166) was more preferred than

car fueled by diesel (−0.244). In contrast, attributes reflecting materialistic values showed overall lower preference scores, ranging from −0.099 to 0.099.

The conjoint analysis produced a total of 64 choice sets. Analysis of the most and least preferred sets (

Table 3) showed that the highest-rated combinations typically included

experiential purchases,

low monetary value,

casual brands, and

growing forest. The least preferred combinations featured

high monetary value,

prestigious brands, and

material purchases. From the perspective of pro-environmental behavior, there was no single attribute that consistently appeared in the least preferred sets—except for the repeated inclusion of

car fueled by diesel.

The attribute importance analysis indicated that pro-environmental behavior was the most influential overall (51.15%), while materialism-related attributes together accounted for 48.85% of the total relative importance. Among materialism attributes, monetary value had the greatest relative importance (19.08%), followed by prestige (15.6%) and tangibility (14.17%).

Prior to correlation analysis, exploratory factor analysis was conducted for the scales measuring materialism, pro-environmental behavior, and narcissism. Items with low loading weights were removed. KMO values were 0.79 for the Materialism scale, 0.82 for the PEB, and 0.75 for the Narcissism scale. The materialism scale retained three dimensions: Centrality (3 items, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.716), Happiness (3 items, α = 0.716), and Success (2 items, α = 0.658). The pro-environmental behavior scale included two dimensions: Ecologic Citizenship (3 items, α = 0.622) and Conservation (2 items, α = 0.556). The narcissism scale comprised two dimensions: Rivalry (3 items, α = 0.651) and Admiration (3 items, α = 0.809). Although most internal consistency values (Cronbach’s alpha) were within acceptable ranges, a few subscales with fewer items fell slightly below the 0.7 threshold. Given their theoretical importance and prior empirical use, these were retained, but results should be interpreted with caution. Pearson correlation was employed, because variables met the assumption of normality based on the Shapiro–Wilk test (p > 0.05).

A correlation analysis was conducted between individual-level preference scores from the conjoint task and the results of the materialism scale (

Table 4). The success dimension was positively correlated with

prestige preferences (r = 0.345,

p < 0.001). Overall materialism also showed positive correlations with

prestige (r = 0.266,

p < 0.05) and

material purchase preferences (r = 0.247,

p < 0.05).

Further partial correlation analysis controlling for narcissism confirmed a significant association between success and prestige in both low (r = 0.313, p < 0.05) and high narcissism conditions (r = 0.321, p < 0.05), with a slightly stronger relationship observed under high narcissism.

A separate correlation analysis explored the relationship between conjoint-based preferences for pro-environmental behavior and scores from the pro-environmental behavior scale (

Table 5). Notably, higher pro-environmental behavior scores were negatively associated with preferences for

no recycling (r = −0.271,

p < 0.05) and positively associated with

fossil fuel transport (r = 0.287,

p < 0.05).

Partial correlation analysis including narcissism as a control variable revealed that pro-environmental behavior and conservation scores remained significantly negatively correlated with no recycling. In the low narcissism condition, pro-environmental behavior was correlated with no recycling at r = −0.309 (p < 0.05), and conservation at r = −0.257 (p < 0.05). Under high narcissism, the correlations were r = −0.309 and r = −0.275, respectively (both p < 0.05).

6. Discussion

The findings provide partial support for the hypotheses and offer valuable insights into how materialistic and pro-environmental values manifest in preference-based decision-making tasks.

H1 was supported. The conjoint analysis results demonstrated a clear respondent preference for profiles characterized by low materialism and high pro-environmental values. In contrast, the least preferred profiles reflected high materialistic values and low pro-environmental orientation. These results align with the conclusions drawn in

Hurst et al. (

2013), reinforcing the notion that individuals tend to devalue options associated with materialistic traits when environmentally friendly alternatives are present. This aligns with broader literature suggesting that consumers’ environmental concern increasingly overrides self-centered consumption motives, at least in hypothetical choice contexts.

H2 was not fully supported. While the success dimension of materialism was significantly associated with preferences for prestige, no consistent significant correlations emerged for other materialism dimensions. This suggests that specific facets of materialism, such as the pursuit of success, may more strongly influence consumer preferences than others. This reinforces previous findings by

Workman and Lee (

2011) that materialism is not a unitary construct, and that success-oriented materialism—tied to public image and social recognition—may be more predictive of status-driven preferences than dimensions linked to happiness or centrality. From a theoretical standpoint, this finding emphasizes the need to disaggregate materialism dimensions in future studies to avoid masking such divergent effects.

H3 was partially supported. Significant correlations emerged between pro-environmental behavior scores and the preference to avoid non-recycling, indicating that those with stronger ecological values are less inclined to choose unsustainable options. This relationship is consistent with the patterns reported by

Thomas and Sharp (

2013), who emphasized that pro-environmental values could predict behavior in specific domains like waste management. However, the relationship was not consistently significant across all pro-environmental attributes, suggesting limited generalizability of value-behavior alignment. However, the absence of significant correlations across all pro-environmental attributes underscores the persistence of the attitude–behavior gap (

Kollmuss & Agyeman, 2002), where stated ecological values do not always translate into behaviorally consistent decisions.

With regard to narcissism, no statistically significant moderating effects were found. While it was hypothesized that narcissism might amplify materialism-driven choices or attenuate value-based pro-environmental decisions due to self-enhancement motives, the data did not support this. This finding may indicate that narcissism’s influence on behavior requires greater situational salience, such as social visibility or status signaling. Previous studies (e.g.,

Griskevicius et al., 2010) have shown that image concerns often activate under conditions of public scrutiny, which were not explicitly manipulated in this experiment. Thus, narcissism’s role might still be context-dependent and worthy of further exploration under different boundary conditions.

Theoretically, this study contributes to a more nuanced understanding of dual-attitude models as one of the possible explanators for theoretical gap, showing that behaviorally expressed preferences do not always match attitudinal responses (

Wilson et al., 2000). Our findings demonstrate that this misalignment can, in part, be explained by the interaction between materialistic values and narcissistic tendencies, where the latter amplifies identity-driven motives and reputational concerns. The success-materialism effect highlights how instrumental environmentalism may emerge—not because of internalized values but because certain pro-environmental choices can symbolically support ego-driven goals (

T. Green & Peloza, 2014). This expands on the impression-management perspective, wherein individuals may adopt seemingly altruistic behavior to enhance reputation, especially when such choices are identity-relevant.

Beyond theoretical insights, the findings of this study carry important practical implications for policymakers, marketers, and behavioral designers. For policymakers, understanding that materialistic and narcissistic consumers may adopt pro-environmental behaviors when such behaviors are socially rewarded suggests that policy interventions and public campaigns could be designed to leverage reputational motives. For example, labeling systems, public recognition programs, or social comparison mechanisms could highlight the status-enhancing aspects of sustainable consumption, thereby increasing participation among otherwise less intrinsically motivated consumers. For marketers, our results suggest that green products and services can be positioned more effectively by framing sustainability in terms of self-enhancement benefits rather than purely altruistic motives. Marketing strategies emphasizing prestige, innovation, and exclusivity associated with eco-friendly products may be particularly successful among consumers high in materialism or narcissism. Finally, for behavioral designers, the study provides actionable insights into how choice architectures can be optimized to nudge pro-environmental behaviors. By designing environments where the pro-environmental option aligns with identity signaling and social desirability, interventions can harness consumers’ extrinsic motivations rather than relying solely on intrinsic environmental concern.

Overall, the study reinforces the idea that people tend to favor pro-environmental and less materialistic consumption profiles, but that this pattern is not always fully aligned with their stated values. Select dimensions of materialism, particularly success, appear to shape specific preferences. Pro-environmental values show limited but targeted predictive power, especially in cases involving clear moral or ecological trade-offs. Narcissism, while potentially relevant in other domains, did not exhibit a notable effect on these dynamics within this study.

7. Research Limitations and Future Directions

While this study offers valuable insights, several considerations highlight opportunities for refinement in future research. First, the sample size of 71 respondents, though sufficient for exploratory purposes, presents room for expansion in future studies to enhance statistical power and generalizability (

Trochim & Donnelly, 2022). Second, the chosen conjoint design limited the independence of pro-environmental behavior dimensions as attributes, which may have influenced the perceived importance of these attributes. Due to the limited sample size, moderation effects were explored using partial correlations and dichotomized variables rather than formal regression models with interaction terms. Future research should apply regression-based moderation analysis to more rigorously test interaction effects and enhance interpretability. Additionally, the null effects observed for narcissism should be interpreted with caution. The use of a median split to dichotomize narcissism scores may have reduced statistical power and sensitivity to detect interaction effects. Moreover, the relatively low variance in narcissism scores within the sample may have limited the ability to observe its moderating role. As narcissism was measured rather than manipulated, future research could benefit from experimental designs or larger, more diverse samples to more precisely assess its interactive effects on the value–behavior gap. Future research may explore alternative designs like simulated shopping or more sophisticated conjoint frameworks (e.g., adaptive conjoint) that allow for a more granular treatment of pro-environmental constructs.

In addition, while the pro-environmental behavior scale used (

Brick et al., 2017) provided a structured framework, its internal consistency could be improved. Future studies are encouraged to consider updated or more robust measurement instruments and to incorporate longitudinal tracking or ecological momentary assessment (EMA) to better understand behavior in real-world or time-sensitive contexts.

Alternative theoretical frameworks may offer deeper insights. For example, future work could integrate Value–Belief–Norm (VBN) theory, Self-Determination Theory, or explore constructs such as environmental identity, self-control, or long-term orientation to capture motivational and contextual drivers of pro-environmental behavior. These multidimensional constructs may better explain the complex interaction between values, personality traits (e.g., narcissism), and behavioral choices.

Lastly, the use of a convenience sample served the goal of timely data collection; however, future work may benefit from broader or randomized sampling strategies to improve the representativeness of the findings.